One of the most indelible scenes from Modern Times, the 1936 Charlie Chaplin film about the dreary life of an oppressed factory worker in Depression-era America, has Chaplin’s character strapped to a contraption that feeds him automatically, leaving his hands free to continue working on the assembly line below the dining platform.

In the film, the scientists behind the feeding machine market it to the factory owner as “a practical device which automatically feeds your men while at work. Don’t stop for lunch: be ahead of your competitor. The Billows Feeding Machine will eliminate the lunch hour, increase your production, and decrease your overhead.”

The “Billows Feeding Machine” in Modern Times

While Modern Times was a caricature of a factory worker’s life, the film contains much truth, especially in how it illustrated the burgeoning preoccupation with time during the Industrial Revolution. An era marked by drastic shifts in culture, economics, politics, and technology, the Industrial Revolution was also characterised by an evolution in how time was perceived.

Propelled by the needs of industry, time as a concept became synonymous with profit. Eventually growing to permeate all levels of society and industry, this time consciousness had a profound impact on the world that continues today.

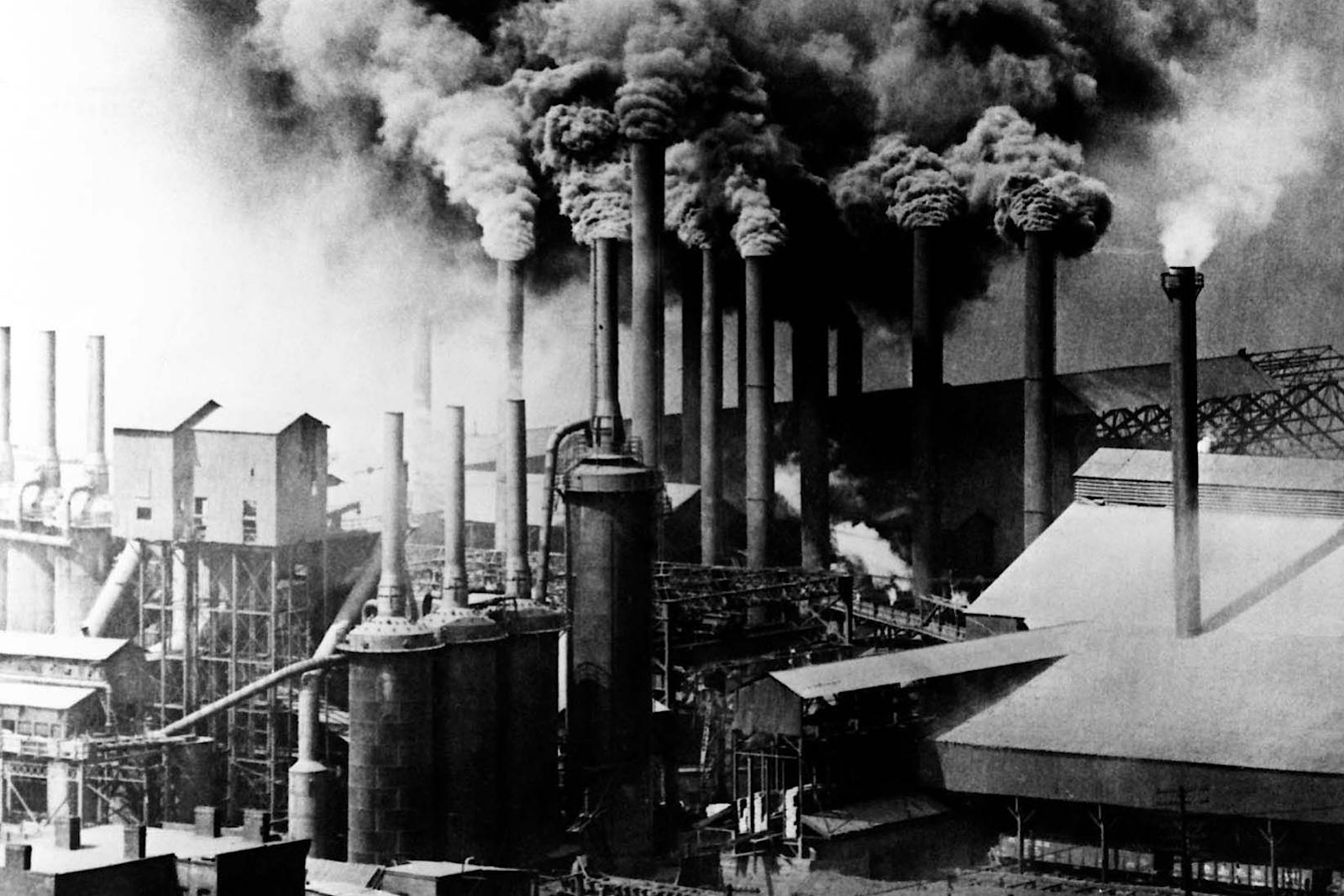

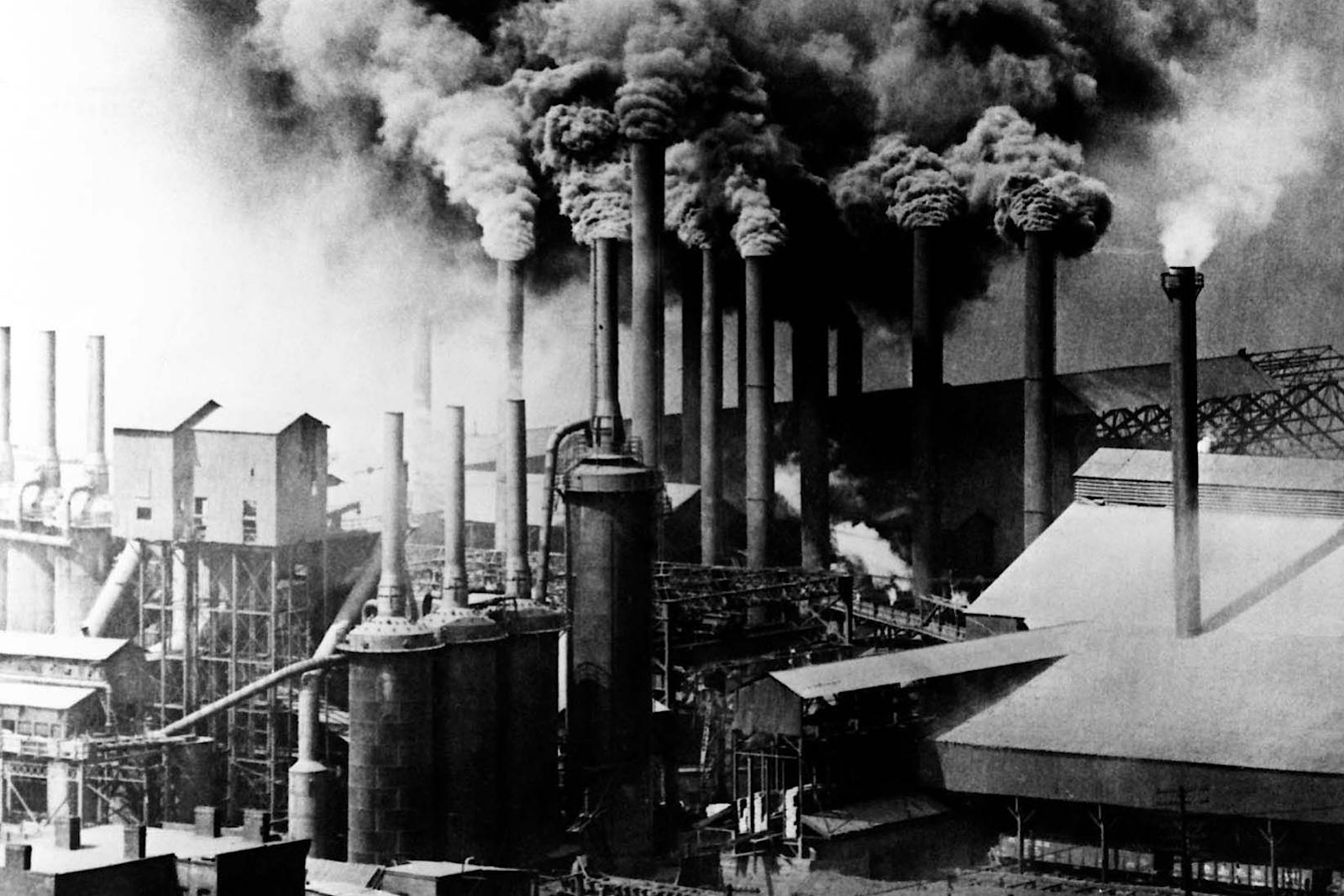

A landscape of factories

Predominantly agrarian and rural societies were transformed during the Industrial Revolution, becoming industrialised and urbanised. This started in Britain in the second half of the 18th century, before spreading to other parts of Europe and North America.

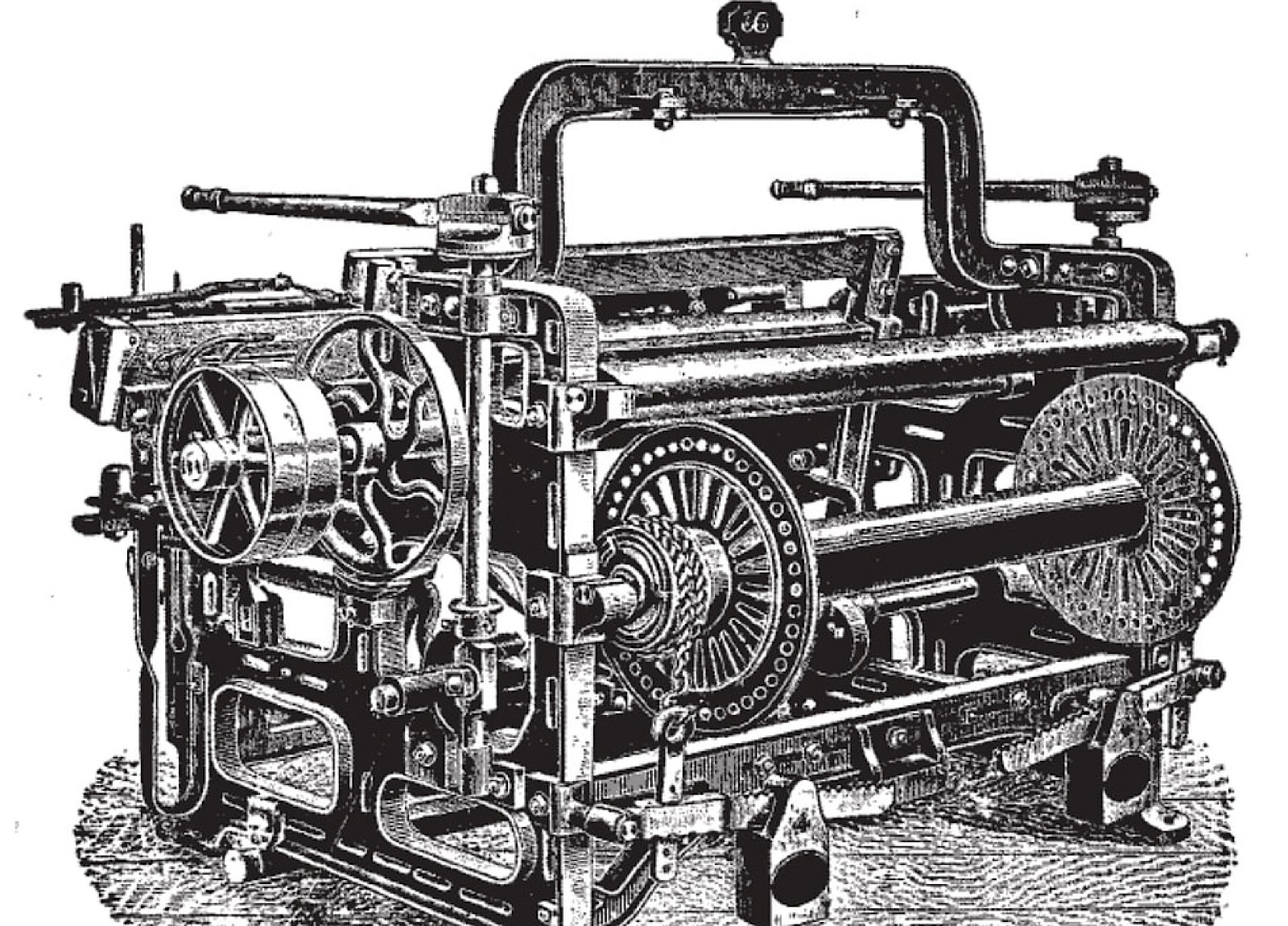

With the proliferation of new manufacturing technologies such as the power loom and the steam engine – perhaps the defining machines of the Industrial Revolution – labour became increasingly mechanised. Industrial output soared as factories steadily expanded in ever-larger cities. This pushed down the prices of manufactured goods, such as textiles and food, which were once made by hand.

Farmers and homeworkers in the countryside could not compete with the lower prices, leading to rural unemployment. That resulted in mass migration from the countryside to cities in the subsequent decades, as rural dwellers sought better opportunities.

Edmund Cartwright’s power loom invented in 1784. Image: History Crunch

With increased automation, and the resulting specialisation as well as mechanisation of labour, most rural migrants to the cities toiled as unskilled labourers, performing tedious and monotonous tasks in massive factories. Long working hours – often 12 to 16 hours a day, six days a week – and extremely low wages were often the norm.

It wasn’t just adults who toiled away in factories. Child labour was particularly rampant, with children as young as five years old being put to work. Often working in dangerous conditions, child workers were nonetheless paid a fraction of what adults earned.

And after a long day in a factory, workers went home to appalling conditions. As urban populations grew in tandem with factories, the result was overpopulation, leading to dilapidated and unsanitary living conditions.

Child labourers during the Industrial Revolution Image: Lewis Hine/The U.S. National Archives

That created a visual landscape of the Industrial Revolution that endures – even today the era conjures up images of bleak urban landscapes with sprawling factories and countless chimneys constantly spewing black smoke, with sooty-faced factory workers toiling below.

However, as much as these were physical and environmental changes that changed the world, they were merely a stage in the evolution of the modern city. But a more enduring psychological phenomenon was also taking place amongst the people who lived and worked in early industrial cities – the changing perception of time.

Factory smokestacks in the Industrial Revolution Image: Bettmann/Corbis

Time orientation

Agrarian societies were the dominant form of organising mankind before the onset of industrialisation. In such pre-industrial societies, people had a disregard for clock time – an artificial construct – and regarded time as synonymous with nature.

People planted, harvested, and went about their days according to natural temporal cycles like the seasons, days, or tides. In fact, clock time in some societies was actually based on natural cycles. In pre-industrial Japan, for instance, life was governed by seasonal time, with days that varied with the season and indicated on seasonal-time clocks known as wadokei.

This notion of time was put forward by British historian E.P. Thompson in his seminal 1967 paper, Time, Work-Discipline and Industrial Capitalism. Thompson labelled it “task-orientation”, where time was based on natural cycles, so a workday would be between sunrise and sunset, rather than between 9:00 am and 5:00 pm.

And work was based on completing the task at hand. As a result, there was little distinction between work and leisure, as social interactions often intermingled with work, while the length of the workday varied depending on the tasks of the day.

Potato Planters by Jean-François Millet. Image: Museum of Fine Arts Boston

But the Industrial Revolution transformed the perception of time from task- to time-oriented. Now time was “not passed but spent” wrote Thompson, becoming a measurable resource that the employers could harness and expend to maximise output.

As a result, once abstract units of clock time, such as the hours and minutes, became embedded amongst the minds of factory workers who were selling their labour, measured in units of hours, every long working day. And employers unsurprisingly enforced time discipline, while punctuality became a virtue.

The transformation in time perception influenced not only industry, but also biological functions. In stark contrast to task-oriented societies, people in time-oriented society ate and slept not because of hunger or tiredness, but because the clock dictated it was mealtime or bedtime.

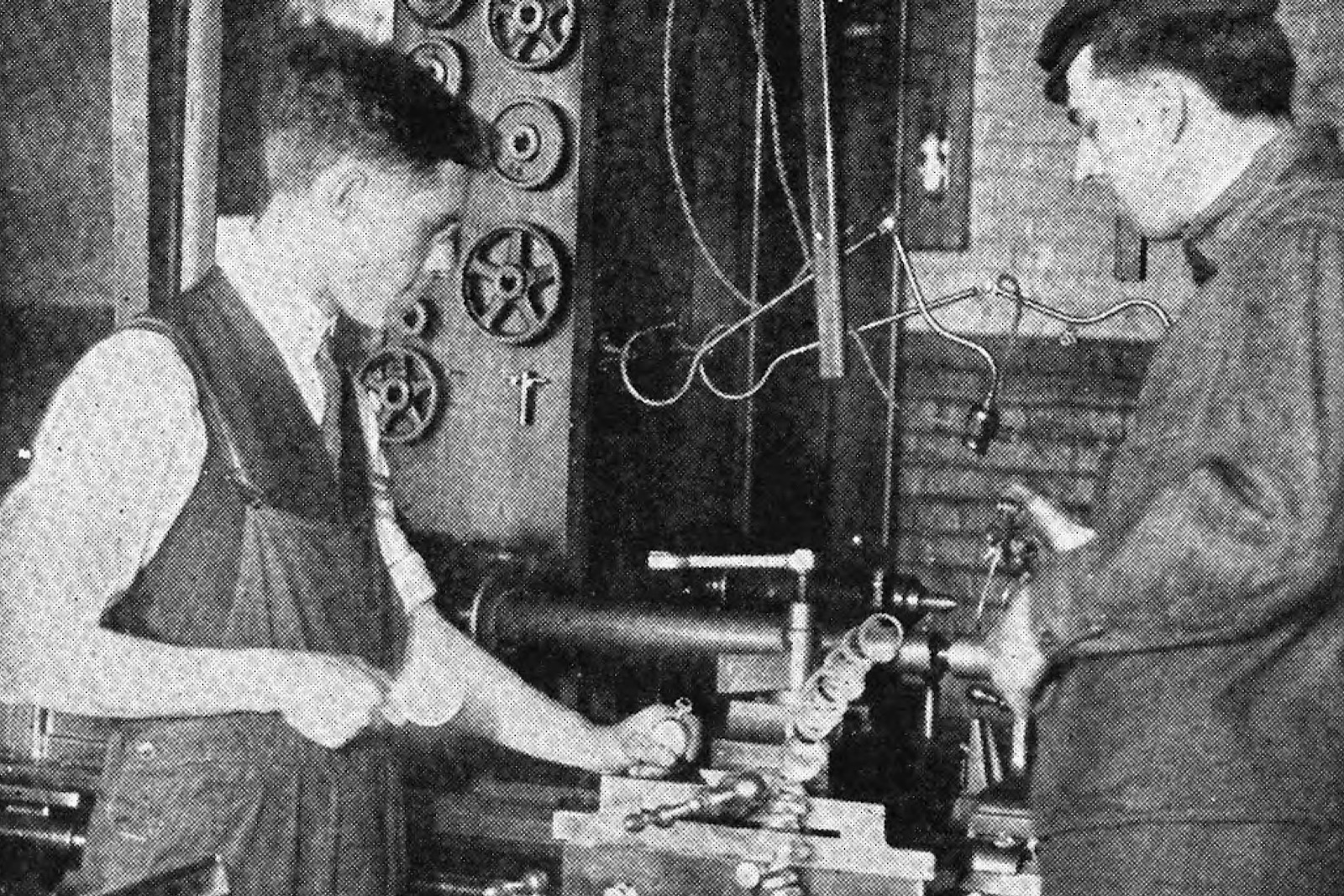

Industrial factory workers. Image: History Crunch

Obsessed with time

With wasted time being forgone potential output, factory owners developed an obsession with time. Contemporary accounts exist of factory owners who deliberately tampered with the clocks in their factories to slow them down, and thus gain more hours – and output – from their workers. Other employers hid the clocks altogether.

James Myles, writing in his 1850 autobiography, Chapters in the Life of a Dundee Factory Boy, recalled his “masters and managers did with us as they liked. The clocks at the factories were often put forward in the morning and back at night”.

More amusing was the existence of the knocker-upper profession that developed in Britain in the 19th century. As most workers had neither alarm clocks nor watches, they hired knocker-uppers to wake them up. The trade was widespread enough in the 1800s that Charles Dickens mentions being “knocked up”, or awoken, in Great Expectations.

Knocker-uppers would use a baton to knock on doors, or a longer stick to tap on bedroom windows. Some developed more ingenious means of waking the workers like Mary Smith, an East London knocker-upper, who used pea shooters to rouse her clients.

Once reliable mechanical timekeeping became cheap and commonplace, such primitive methods were dispensed with. Though knocker-uppers disappeared by the early decades of the 20th century, they persisted until the 1970s in a handful of industrial areas in northern England.

Knocker-upper using a long pole to wake up clients who lived on upper floors. Image: J. Gaiger/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

Mary Smith using a pea shooter to wake her clients. Image: The Image Works

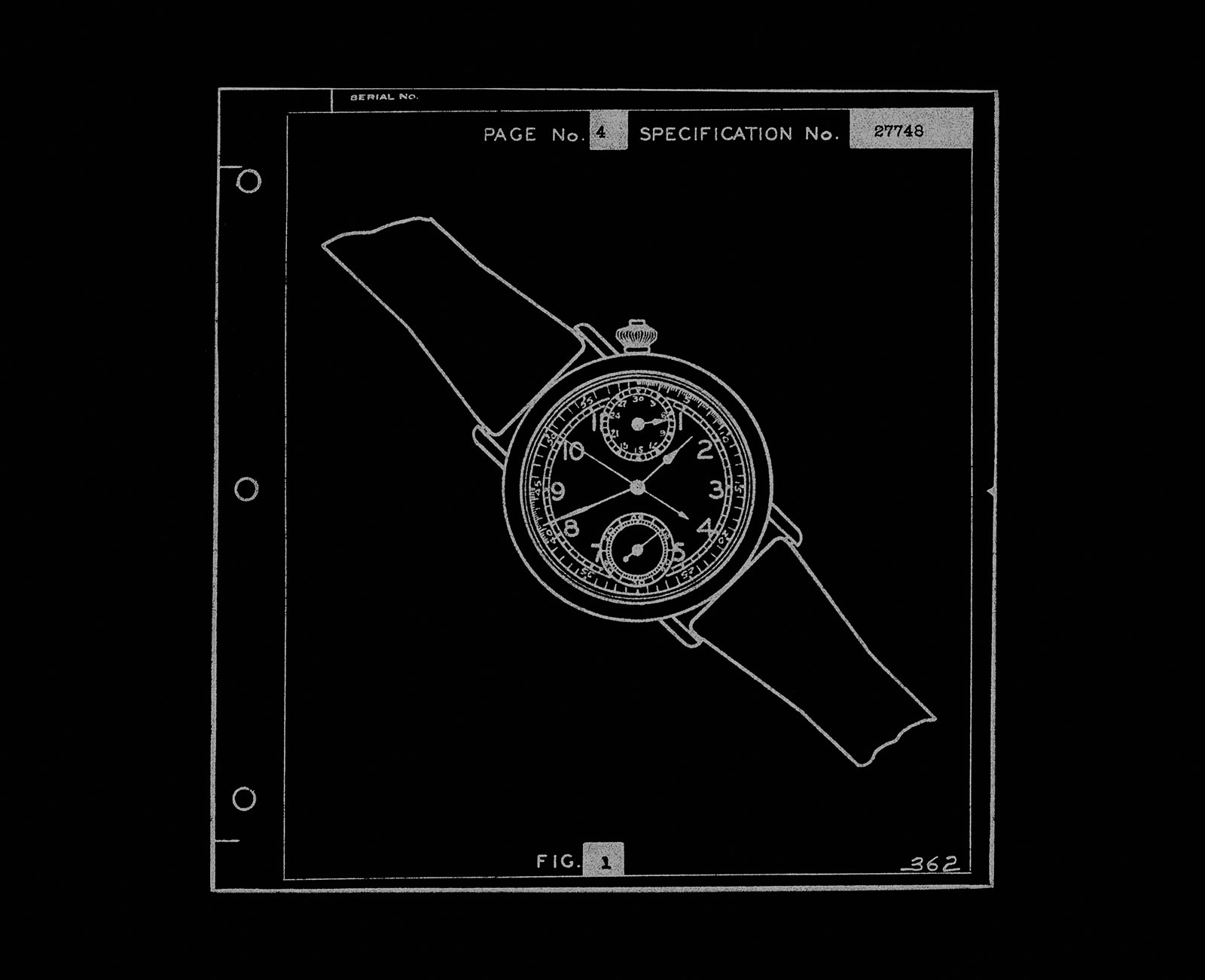

The proliferation of mechanical timekeeping had another consequence, giving employers a new way to track attendance and punctuality, especially in the United States, where the time clock was invented around 1890 by Willard Le Grand Bundy, a New York jeweller whose namesake time clock company would later become part of IBM.

A mechanical device that would stamp the date and time on a time card carried by each worker, the time clock became the gatekeeper to the factory, with each employee required to punch in and punch out. Routine inspections of time cards were conducted by employers, with penalties like wage cuts for being absent or late.

Ford Motor Company workers punching their time cards at the time clock. Image: Getty Images

Perhaps the man who most embodied the industrial preoccupation with time was American engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor. Active during the zenith of America’s Industrial Revolution in the mid-19th century, Taylor dedicated his life to improving industrial efficiency.

Frederick Winslow Taylor

Taylor detailed his numerous methods for optimising production in his influential book, The Principles of Scientific Management. He is perhaps most famous for the time and motion study, where he scrutinised how a particular task was completed by breaking it down into small, discrete actions. This allowed Taylor to identify inefficient actions, and eliminate wasted time.

Sometimes criticised for dehumanising workers by treating them as mere cogs in a machine, Taylor’s rigorous approach to maximising output is influential across industries long after his death. Taylorism even shaped Toyota’s vaunted Toyota Production System.

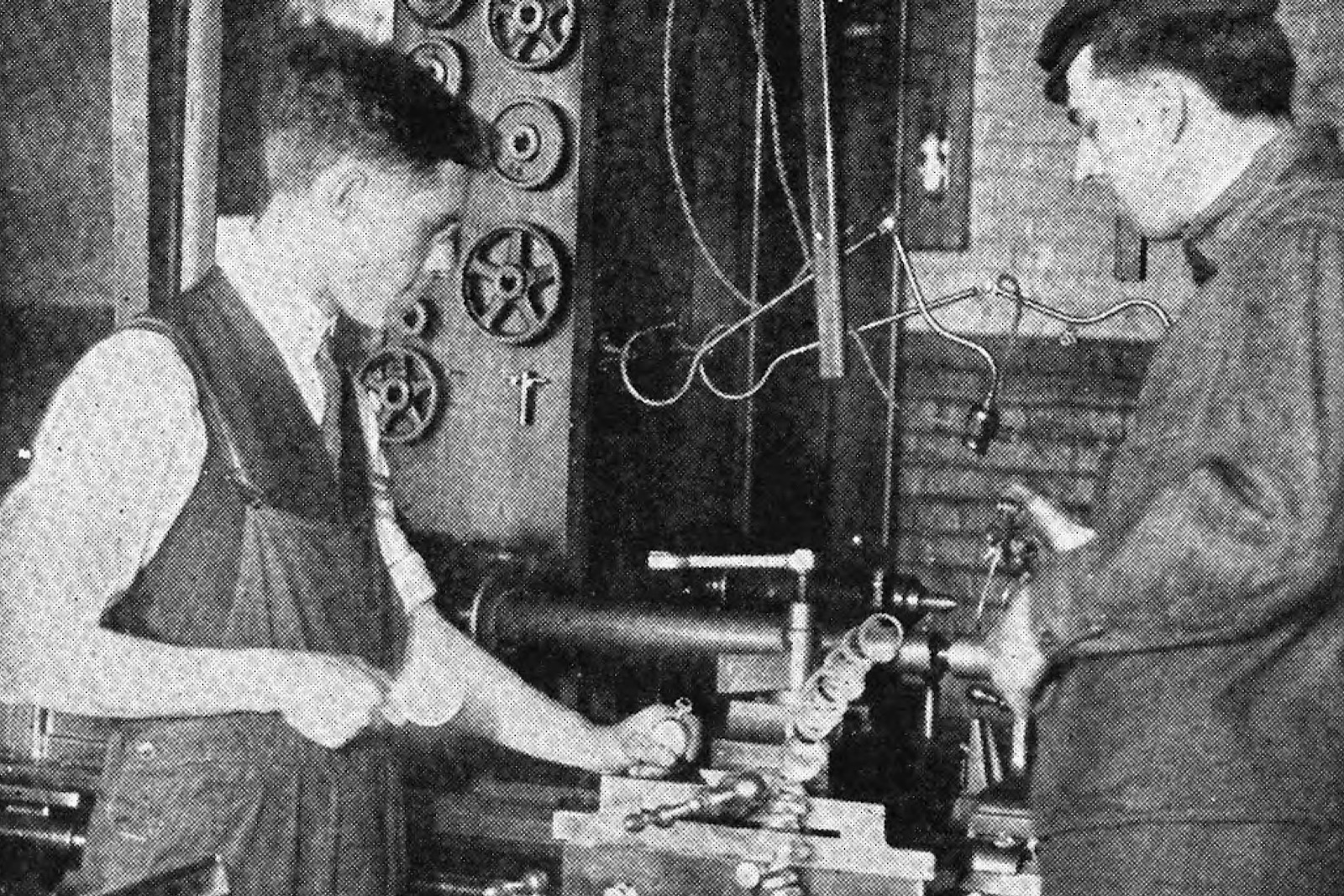

A time engineer timing and evaluating equipment. Image: How Scientific Management is Applied

Possessing time

Timekeeping was paramount in determining the lives of workers, but also crucial for transportation. Much of the success of the Industrial Revolution depended on the efficient, countrywide freight networks that delivered raw materials to factories or finished products to markets.

First in Britain and then the United States, railroads played the central element role in this network, Sophisticated and complex transportation schedules were developed to meet the demands of factory owners, who desired near-perfect synchronisation of labour and raw materials. All of that coordination across national borders, state lines, and time zones, necessitated reliable timekeeping devices.

Housatonic Railroad, 1881 Image: Railroad History Archive

In the first few decades of the Industrial Revolution in Britain, prices of pocket watches and clocks remained out of reach for the average factory worker. Instead, portable timekeepers were mostly owned by factory owners and capitalists, who used them as instruments for business, but also as status symbols.

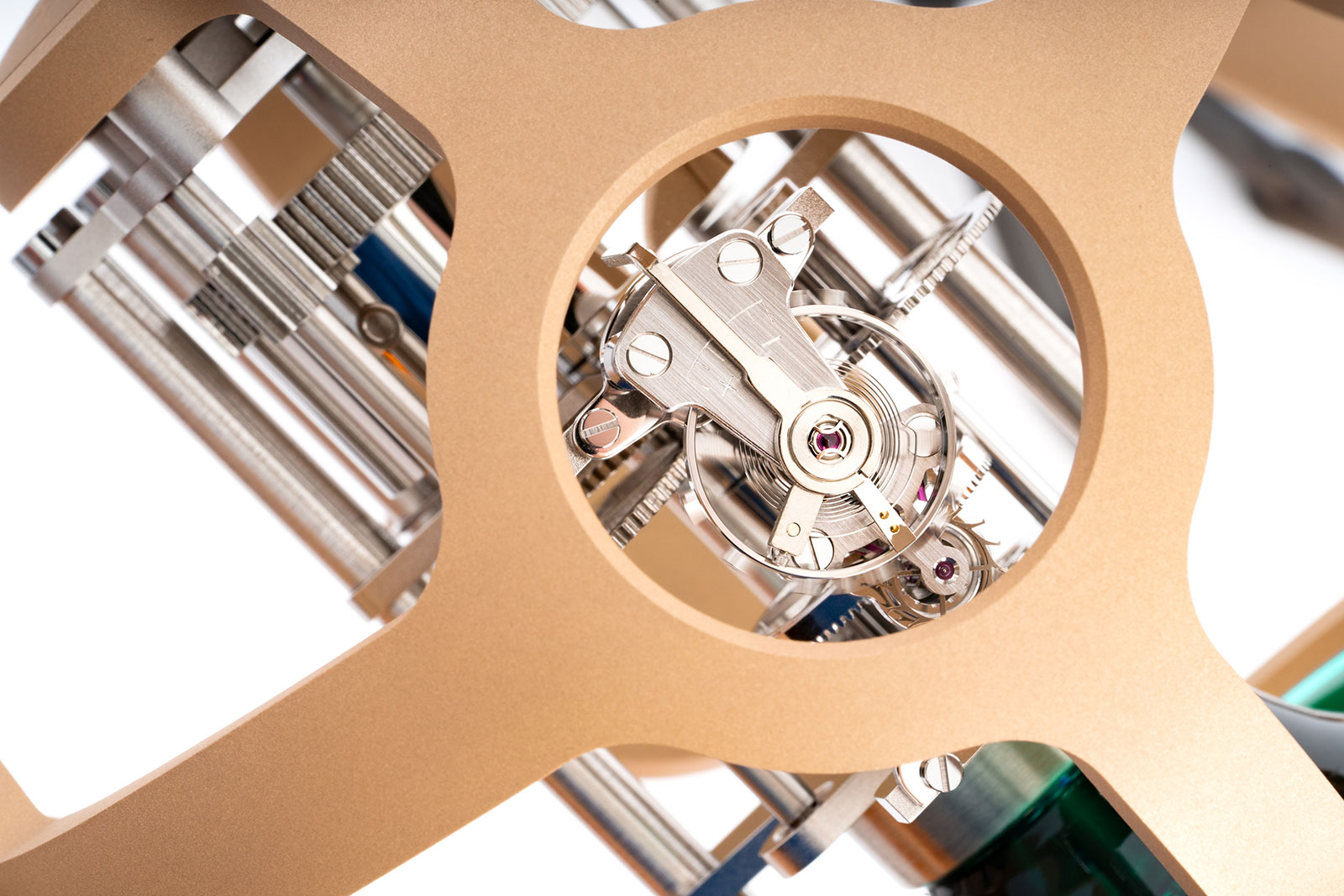

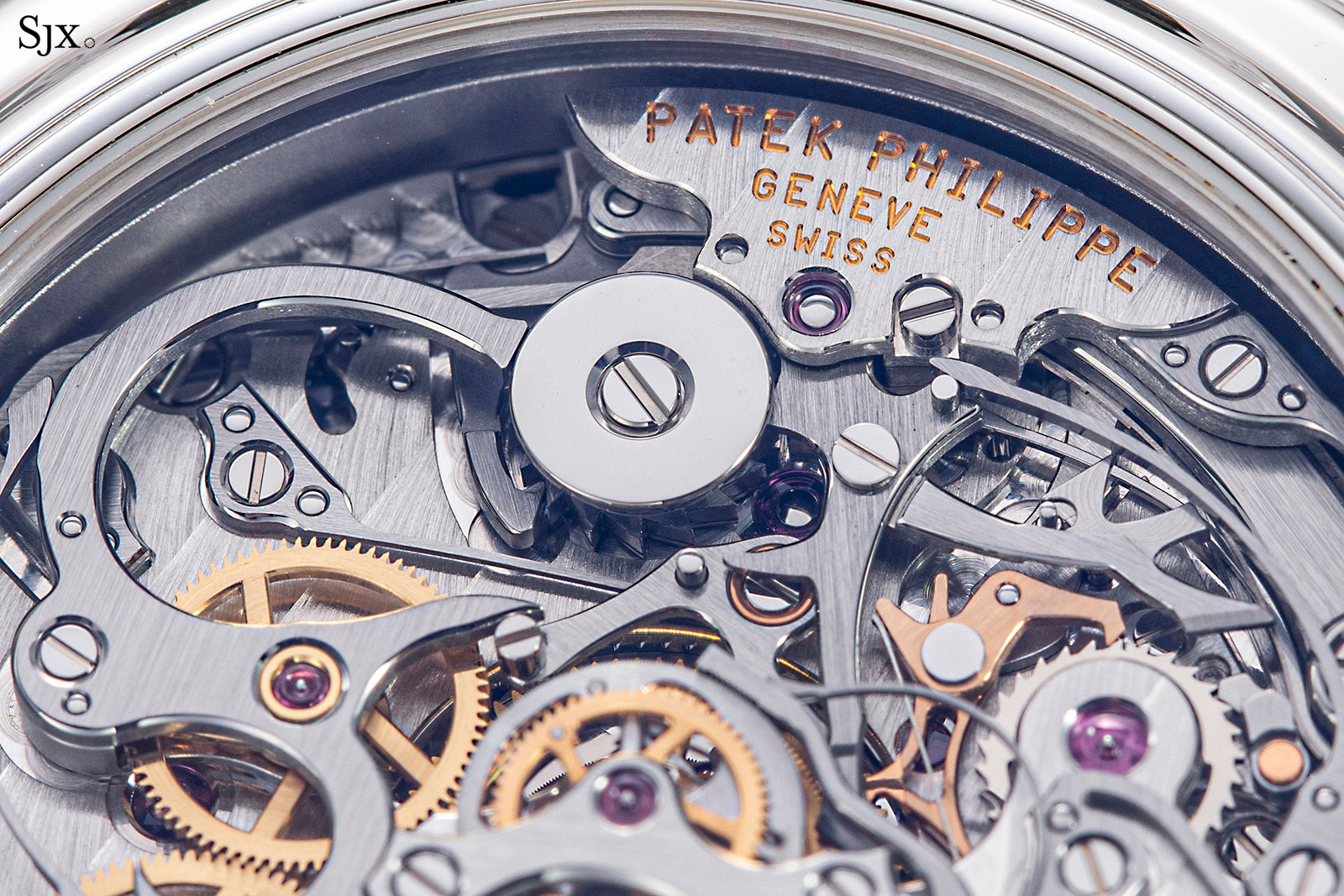

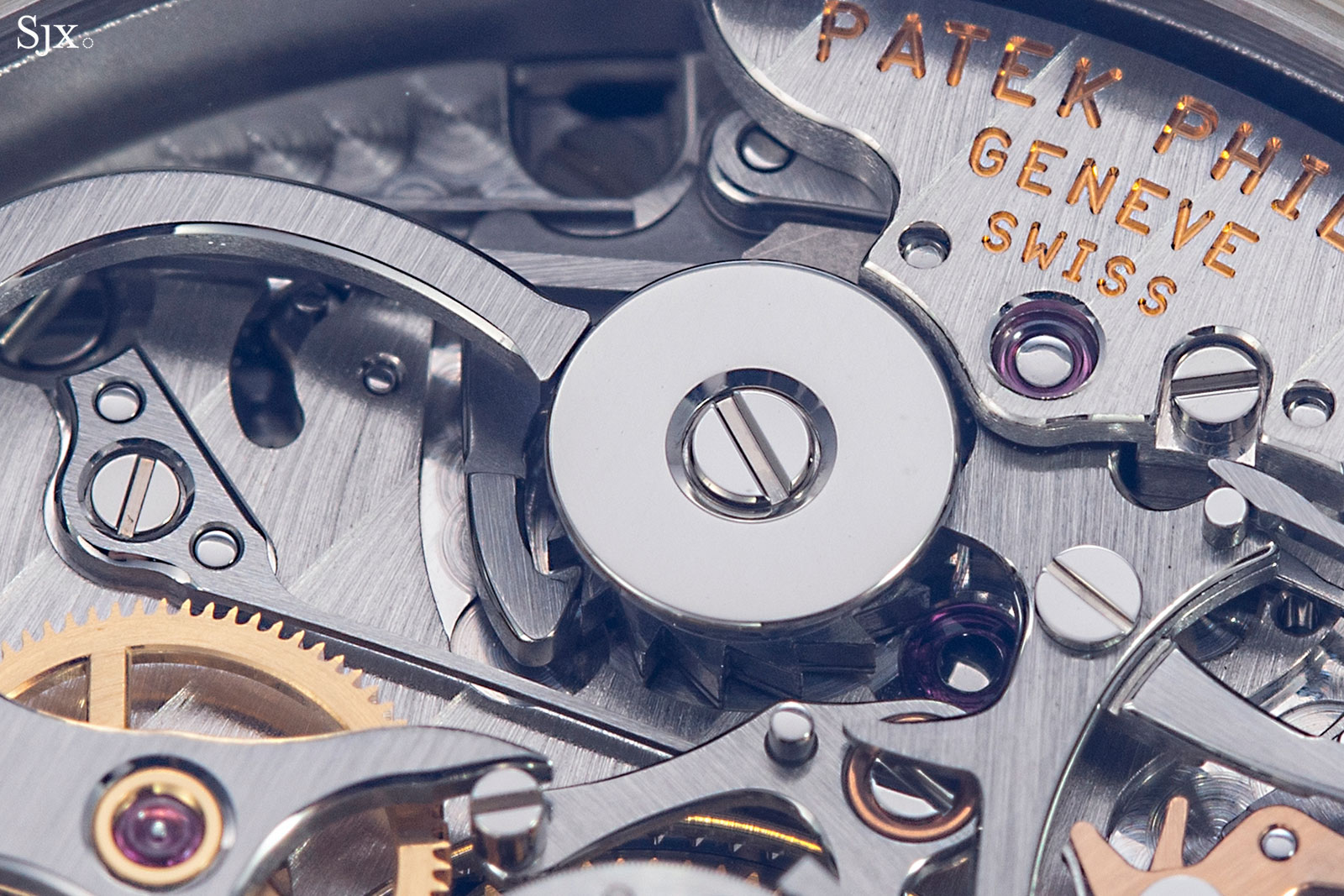

Especially prestigious were keyless pocket watches – a new invention in 1842 by Jean-Adrien Philippe, who later became a partner in Patek Philippe. His keyless winding mechanism allowed the watch to be wound via the crown and stem, dispensing with the traditional key. Such watches were known as “stemwinders”, a nickname that eventually came to describe outstanding people or objects, and later on, rousing oratory.

The allure of owning a pocket watch meant there were factory workers who stretched their meagre resources to obtain one, or splurged when they landed an unexpected windfall.

Pocket watches thus became an important asset for members of the working class who were able to own one. E.P. Thompson, in Time, Work-Discipline and Industrial Capitalism, wrote “the timepiece was the poor man’s bank, an investment of savings: it could, in bad times, be sold or put in hock”.

Some factory workers used watches as a means to reshape power relation between employer and employee, since a worker who owned a pocket watch would be able to contest the dishonest manipulation of production-floor clocks by the factory owner.

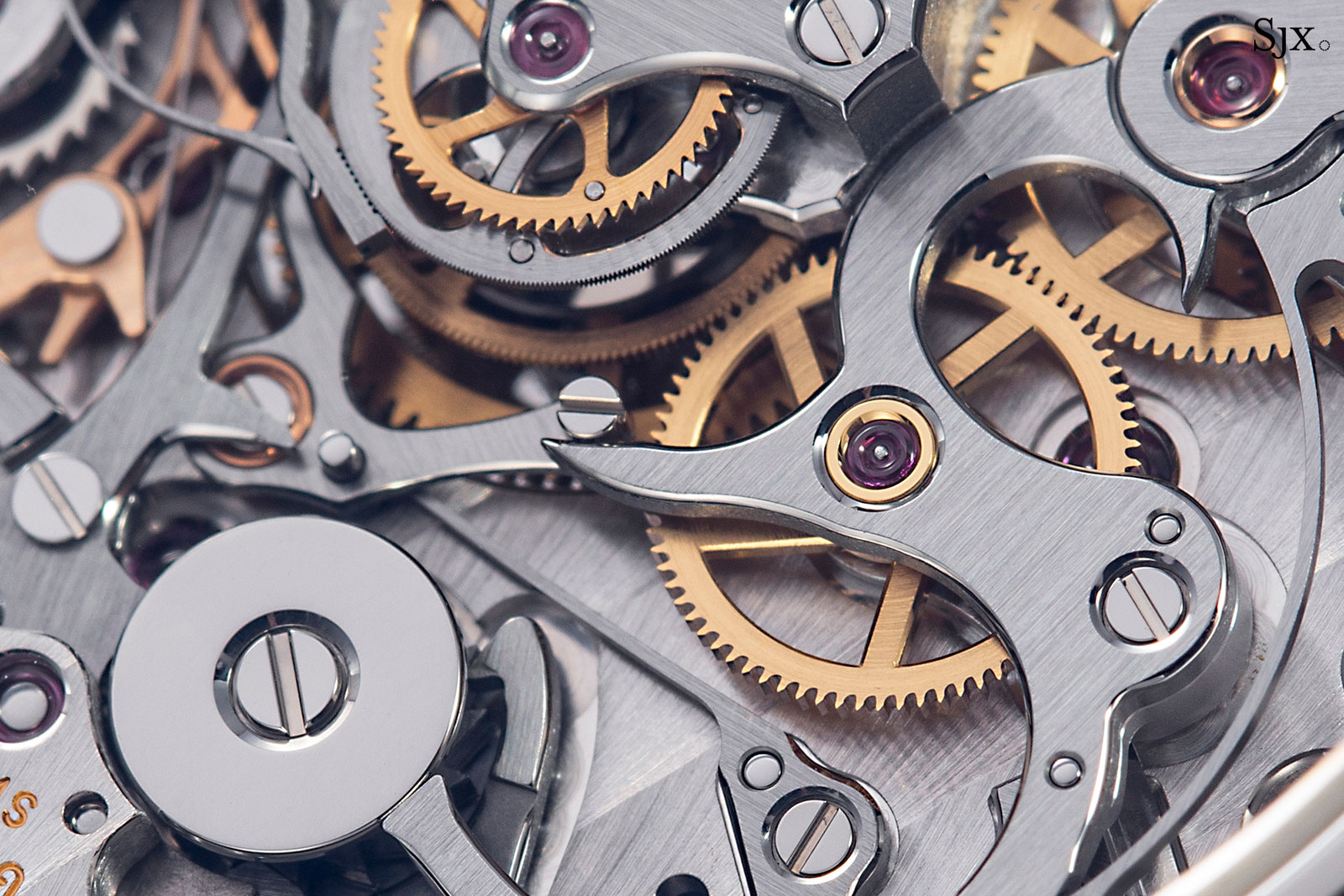

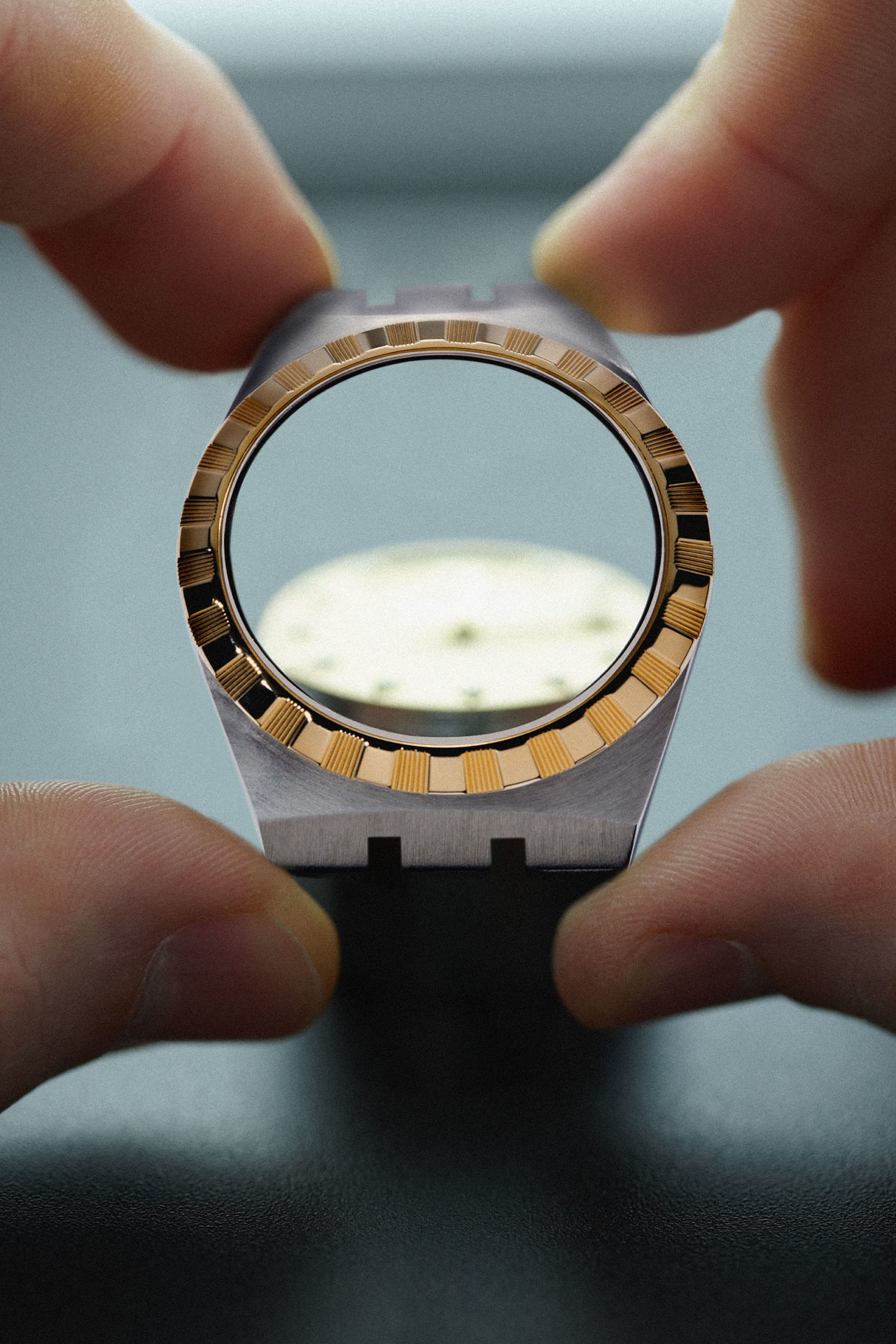

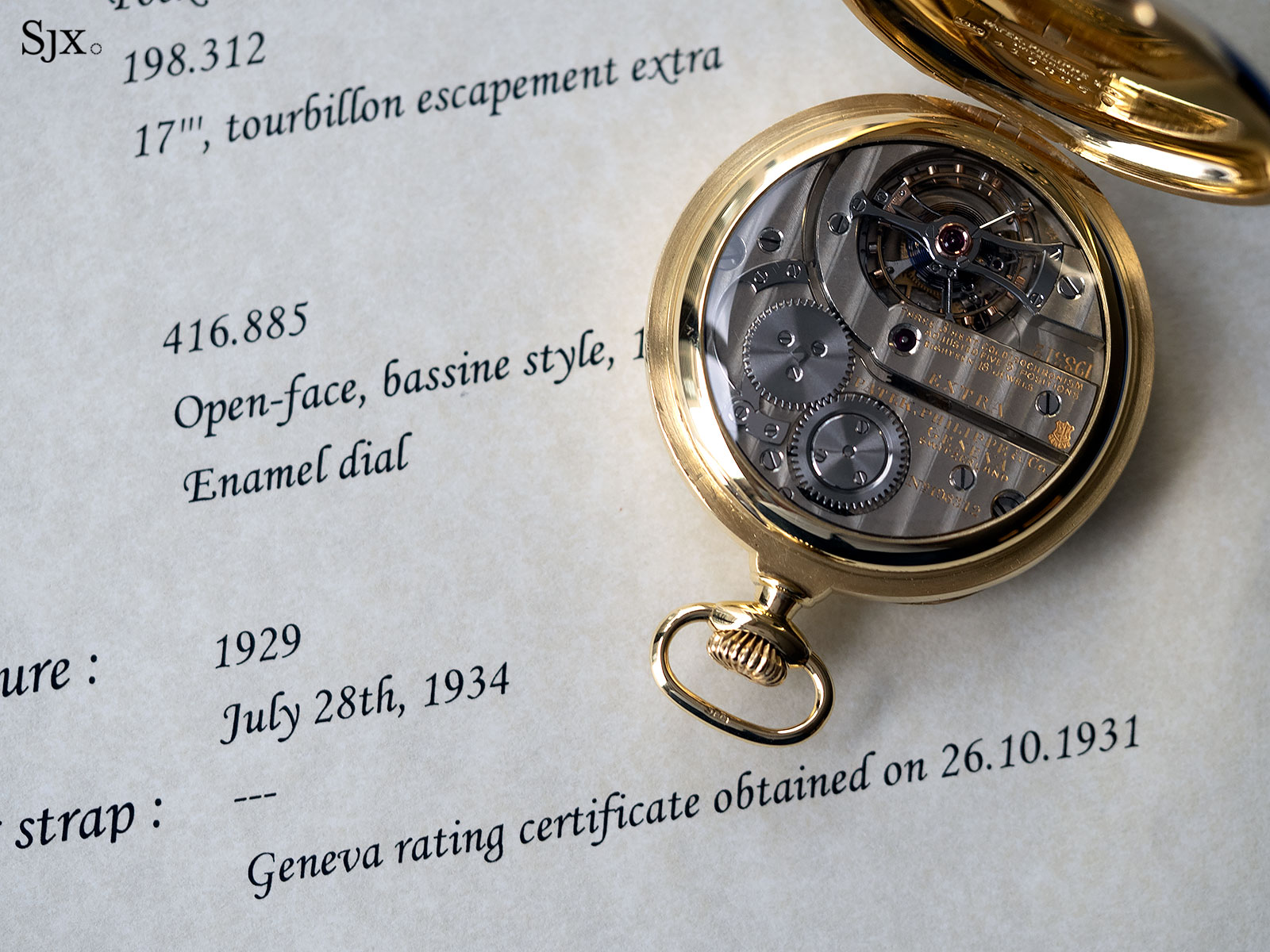

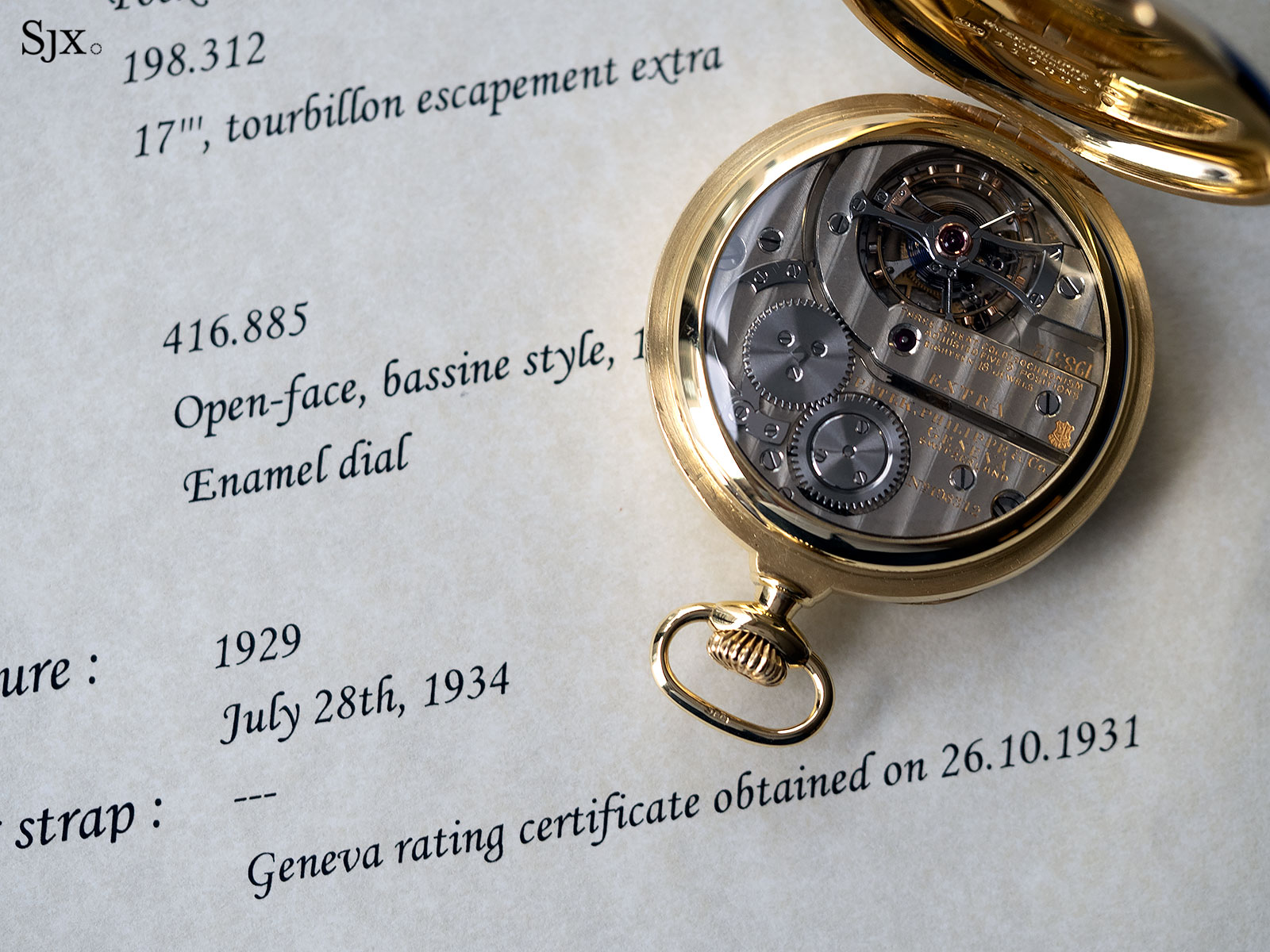

The movement and front of a Patek Philippe observatory tourbillon pocket watch that was sold in 1934, perhaps to a very successful industrialist

The democratisation of time

But as with all manufactured goods, clocks and pocket watches eventually became more affordable as a result of mass production, particularly in the United States during the 19th century.

Regarded as the father of the clockmaking industry in America, Eli Terry pioneered mass production of standardised wooden clock components that were interchangeable from one movement to another around 1800. Soon after, he set up a water-powered clock factory in New England, staffed by a large workforce that produced substantial numbers of clocks and components.

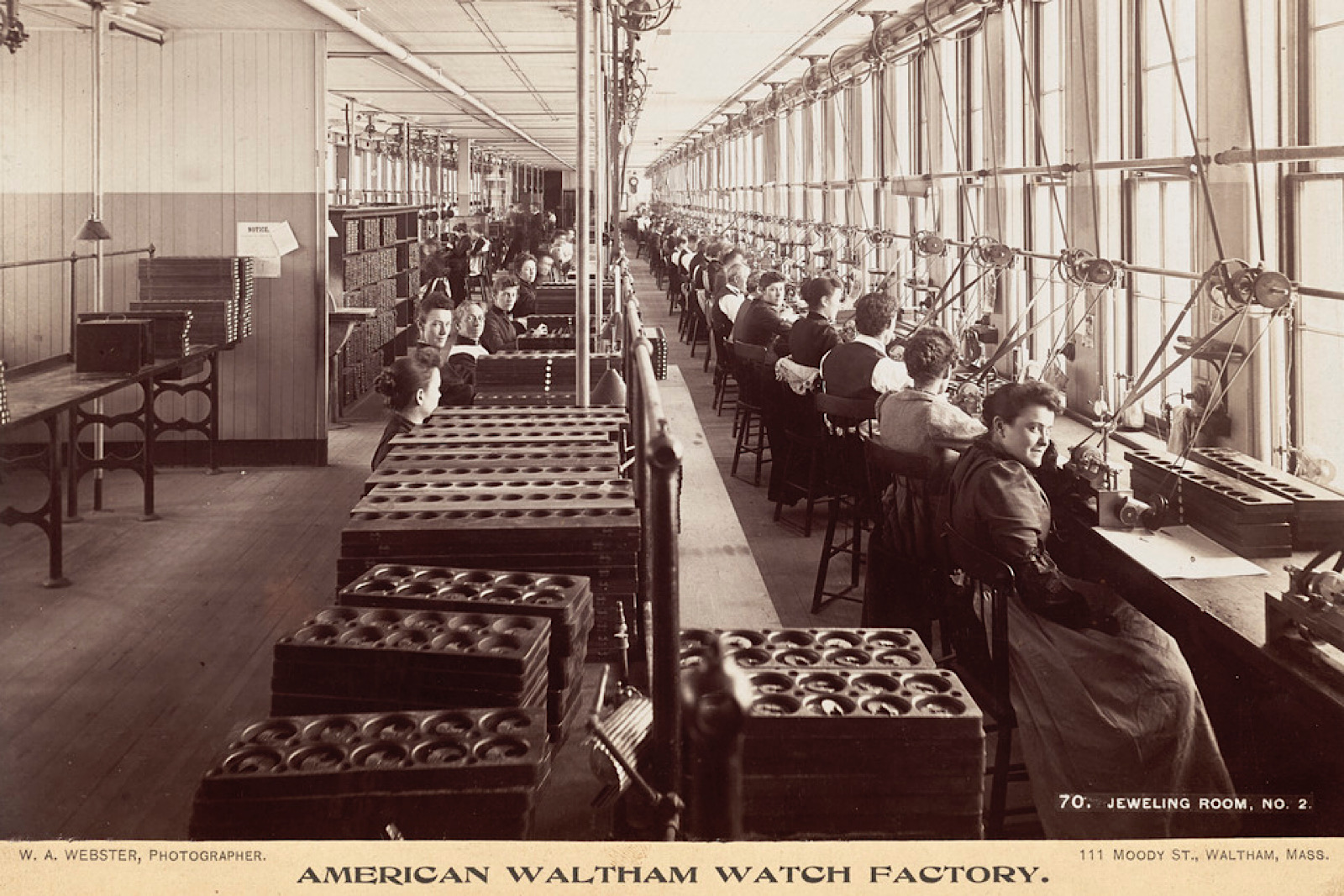

Another milestone in American watch manufacturing came in 1850, when Aaron Dennison, Edward Howard, and David Davis, in a bid to mass produce pocket watches, set up what would become the Waltham Watch Company. The task would prove more difficult than mass producing clocks, as watch movement components were far smaller with more unforgiving tolerances.

Nevertheless, having developed new machines and techniques, the company’s cumulative output totalled 14,000 pocket watches by 1858 according to Timepieces: Masterpieces of Chronometry by David Christianson. Exponential growth followed: by 1865, Waltham had produced some 180,000 pocket watches. The company enjoyed enough economies of scale that its watches were affordable for the average American worker.

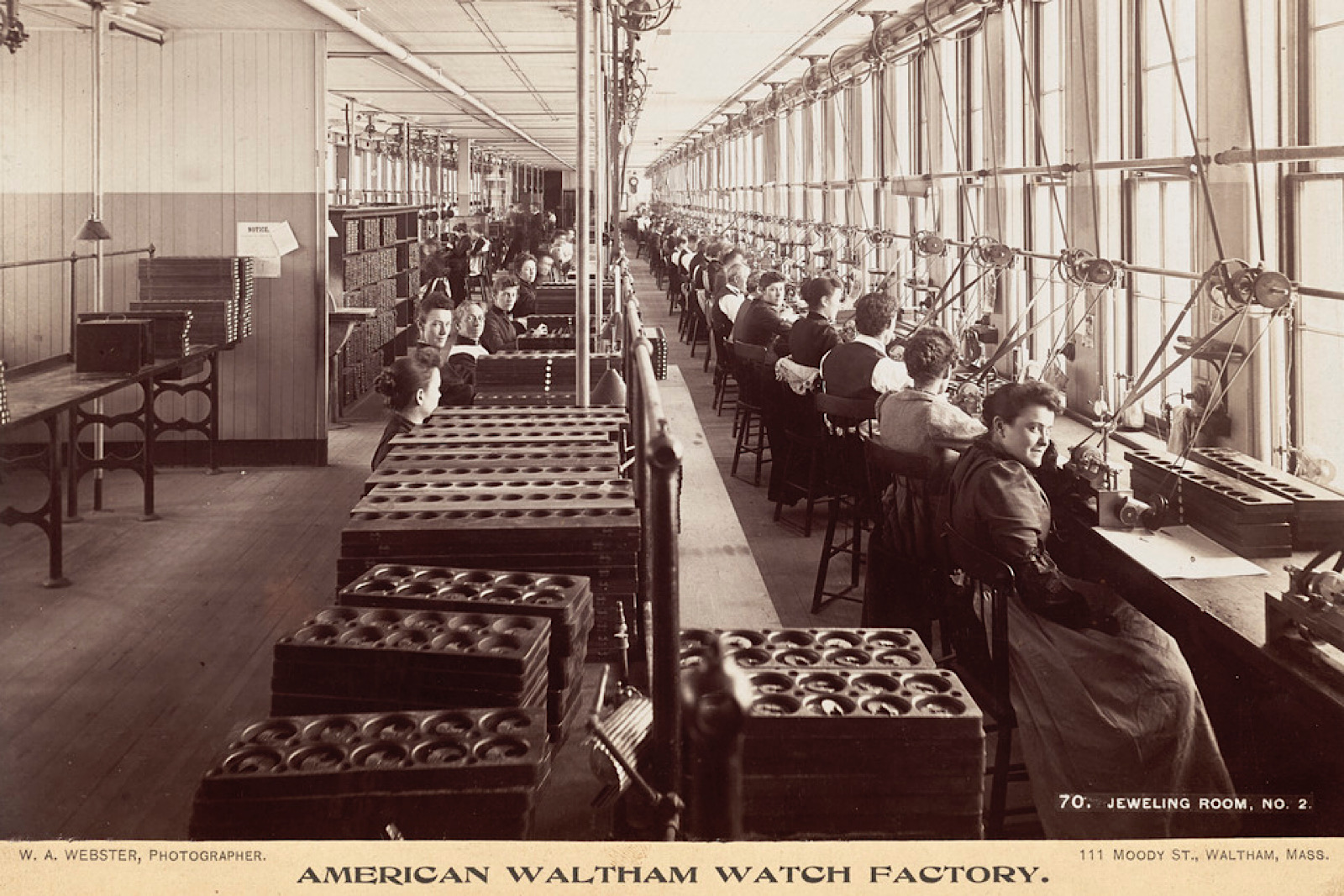

Inside the American Waltham Watch Company factory in the late 1800s. Image: Digital Commonwealth

Split-seconds chronograph pocket watch from American Waltham Watch Company, circa 1886. Image: Christie’s

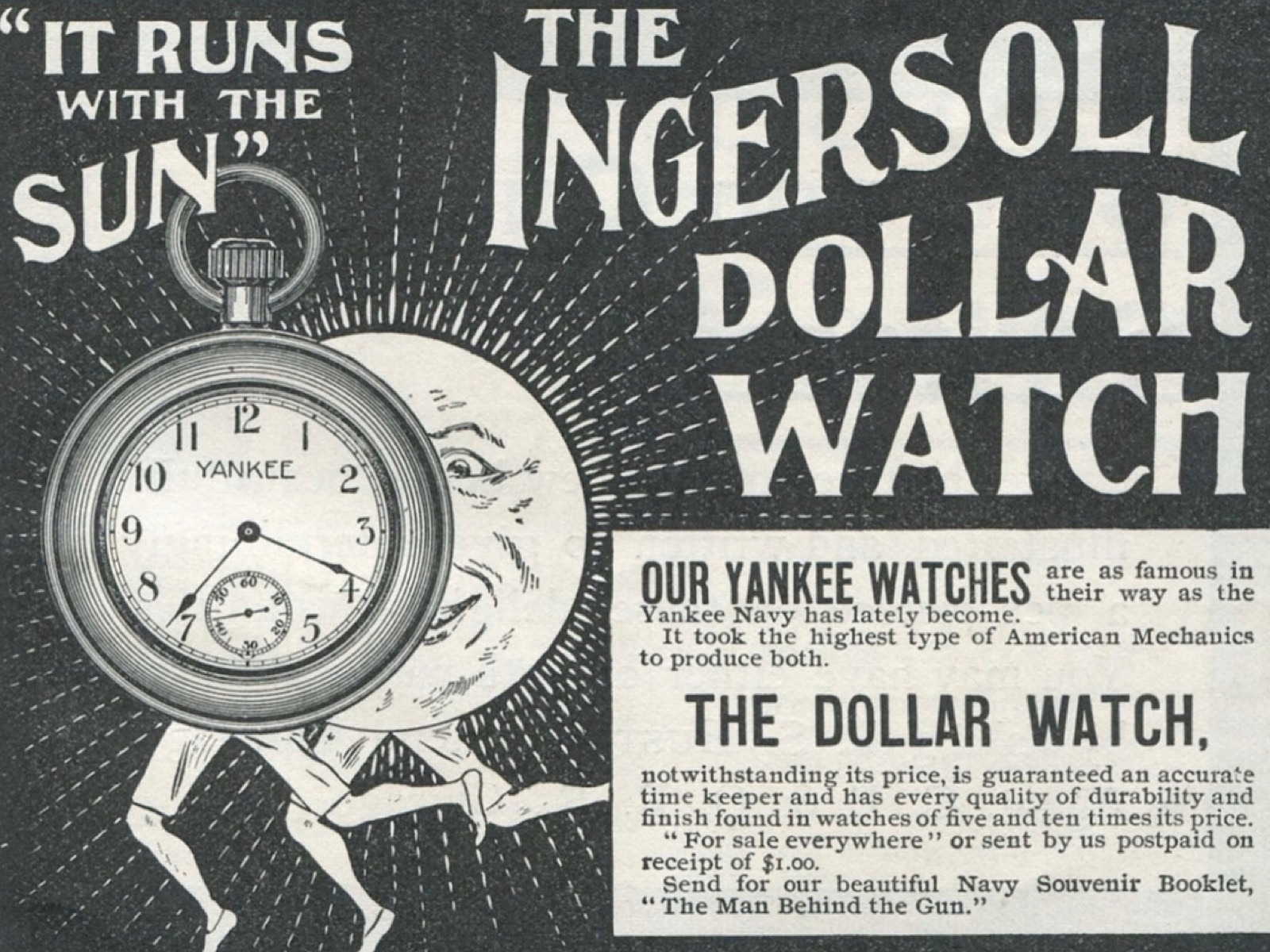

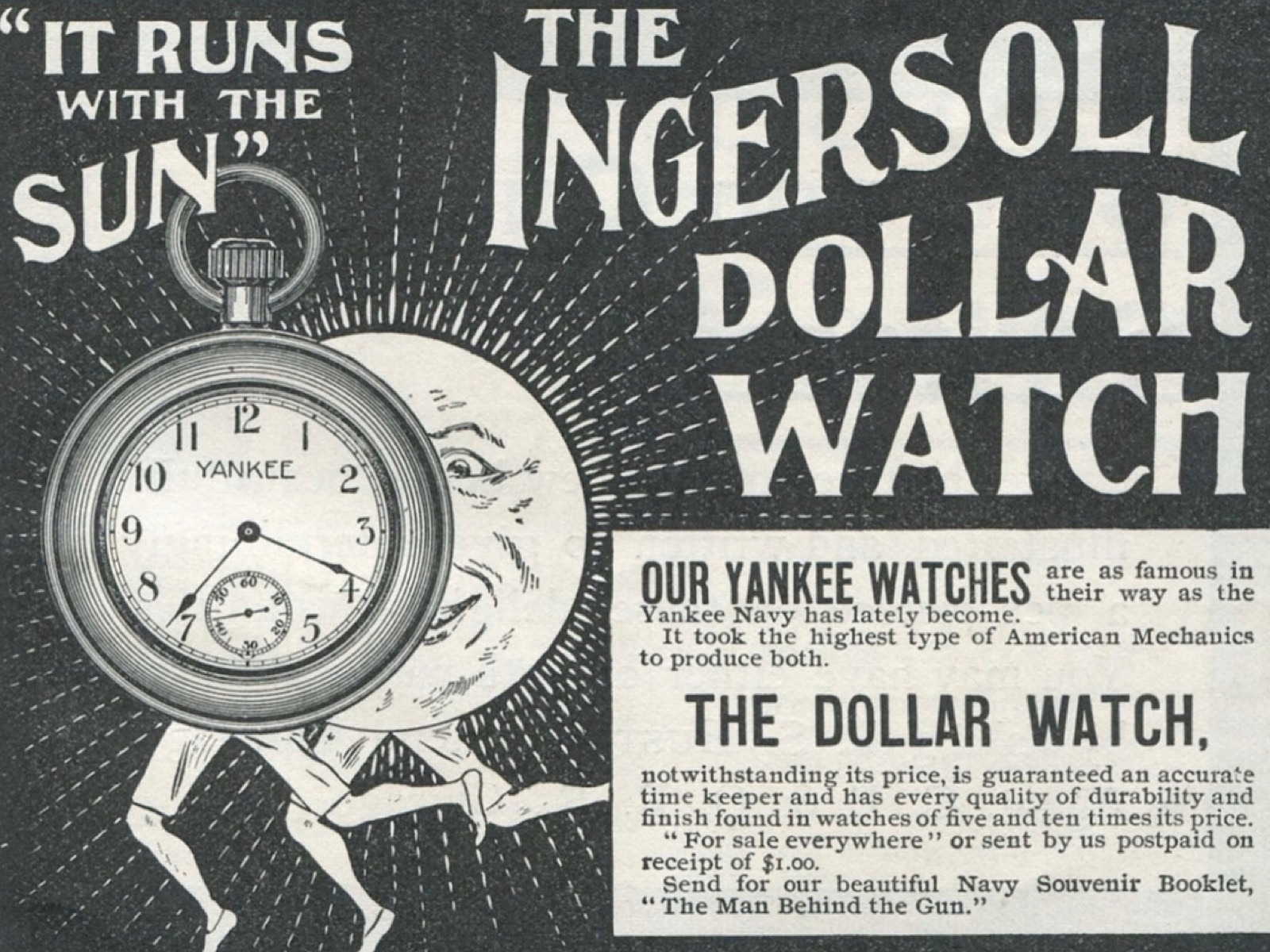

In 1896, another American company, Ingersoll, introduced the Yankee pocket watch. Priced at only US$1, or approximately US$28 today, the Yankee was the cheapest pocket watch on the market and sold with the slogan: “The watch that made the dollar famous”. Like all other “dollar watches” of the era, the Yankee was powered by a cheaply-made but functional movement made up of stamped parts, a pin lever or Roskopf escapement, and no jewels.

American mass-production techniques came to be copied by manufacturers elsewhere, including in Switzerland. In fact, American methods were the rationale behind the foundation of IWC. Though now very much a Swiss brand, the International Watch Company (IWC) was founded in 1868 by an American, Florentine Ariosto Jones, whose plan was to establish an enterprise “combining all the excellence of the American system of mechanism with the more skillful hand labor of the Swiss”.

Eventually, cheap yet reliable timepieces could be found in most waistcoats or trousers, regardless of the wearer’s wealth. More workers possessing a watch allowed for greater industrial synchronisation. The importance of the timekeeper was summed up by American historian Lewis Mumford in his 1934 book Technics and Civilization, where he wrote that “the clock, not the steam engine, is the key machine of the modern industrial age.”

An advert for the Yankee watch. Image: Jay Paull/Getty Images

Modern-day implications

The Industrial Revolution laid the foundations for contemporary, developed societies that are driven by capitalism and anchored to a time consciousness and discipline that continues to prevail today.

The cliche “time is money” still rings true, and many workers, including highly-paid, white-collar professionals, continue to be remunerated on an hourly basis. And while the methods have changed, the power relations between the owners of capital and workers remain the same. The mechanical time clock has been transformed into software that monitors worker activity or biometric scanners that track employees coming and going.

Rush hour in Tokyo, Japan. Image: Chris 73/Wikimedia

Awareness of time is now ingrained, since it is impossible to escape the omnipresence of time that is now displayed everywhere – clocks, watches, and phones, or even microwaves and cars. Society is now governed by schedules and timetables, with workers often struggling to meet deadlines.

These distilled notions of time spurred by the Industrial Revolution demonstrate that even though time itself is grounded in the unchanging laws of physics, it is also very much an inescapable social construct.

Back to top.