Few brands approach marine chronometer-style wristwatches with the intensity of Ferdinand Berthoud (FB). Fewer still have the capacity to produce a watch that is truly hand made. The brand has leaned into these strengths to good effect with the Naissance d’une Montre 3, which is perhaps the most labour-intensive wristwatch ever created.

Marking the third official chapter of the Time Æon Foundation’s Naissance d’une Montre project, the Montre 3 is the byproduct of a six year quest to thoroughly document the steps required to make a chain and fusee wristwatch using only hand-operated tools.

While the production of the Montre 3 involves more than 80 individuals from both FB and its parent Chopard, the labour involved equates to roughly a full year’s work for five people to produce each of the 11 pieces that will be made in the coming years.

Initial thoughts

It’s easy to feel jaded about the smoke and mirrors of luxury watch marketing, with terms like ‘hand made’ and ‘in-house’ used all too freely, making it difficult to separate the signal from the noise.

Make no mistake, the Montre 3 is, in some ways, what all traditional haute horlogerie watches aspire to be, and takes the concept of hand craftsmanship to its absolute limit. The Montre 3 is neither inventive nor complicated, but the intrinsic quality of its construction is immediately obvious and breathtaking in its own right.

To some extent, the simplicity of the 44.3 mm white gold case demonstrates the limitations of hand craft. When the Ferdinand Berthoud brand was reborn a decade ago, it introduced an octagonal case design inspired by French and English marine chronometers from the 18th century, but this shape is impractical to produce by hand and requires modern milling methods.

As a consequence, the round case of the Montre 3 is comparatively simple, having been produced using a hand-operated lathe. The lugs are likewise produced by hand and screwed and soldered to the case band. At just 13 mm thick, the Montre 3 is well-balanced on the wrist and fairly sleek as such things go. Despite these antiquated production methods, the case is water resistant to modern standards, rated 30 m, to shield the movement from any aquatic mishaps.

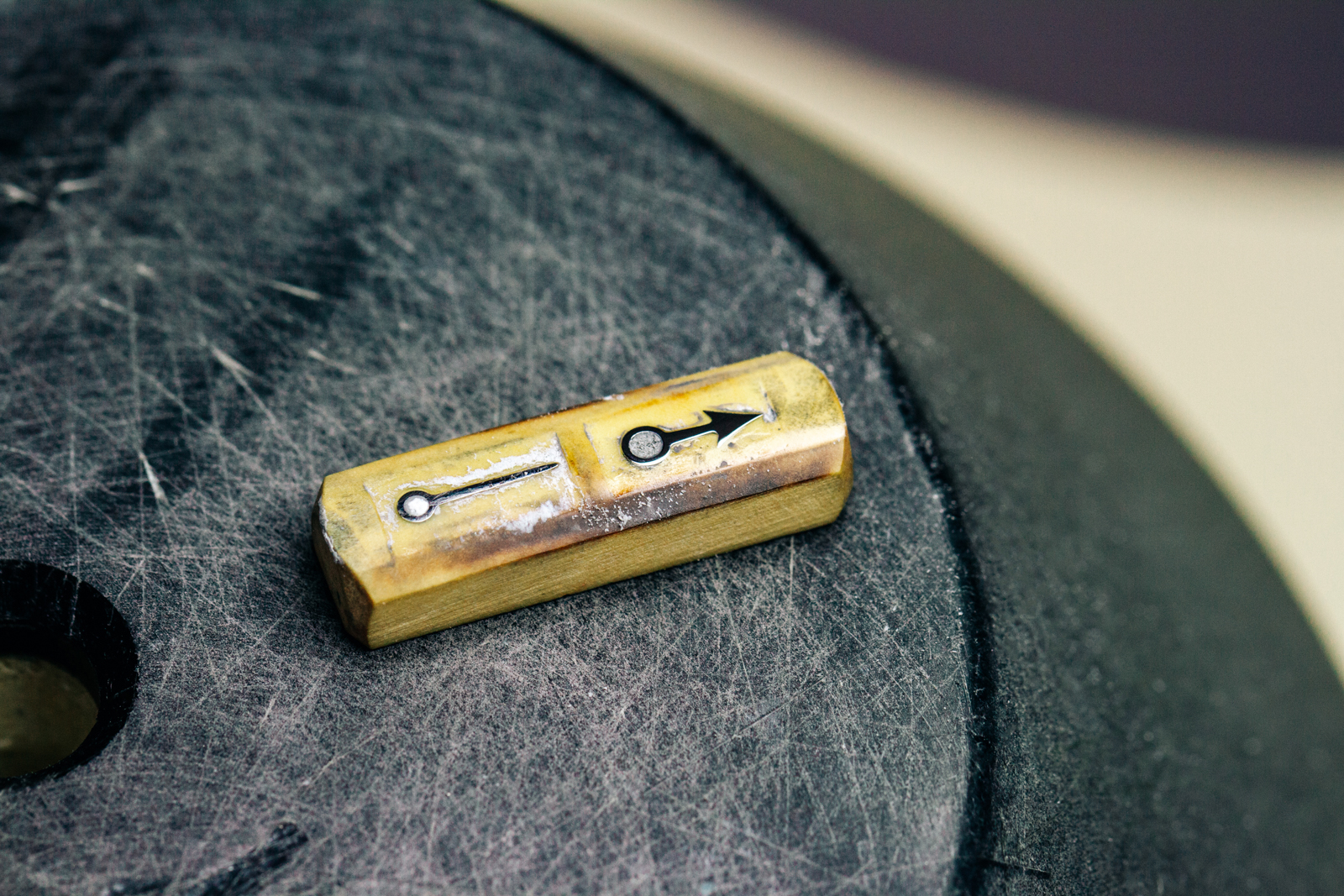

Ferdinand Berthoud, both the man himself and the current brand, was well known for quirky regulator-style time displays. Given this reputation, reading the time on the Montre 3 is refreshingly simple, with hours and minutes read against an offset sub-dial. As befitting a chronometer-style watch, the slender seconds hand gets top billing, read against the dial flange.

Both dials are free-hand engraved, and while it’s difficult to point to any single imperfection, the markings exhibit the unmistakable signature of a human touch, which lends a charming warmth to the design.

The minimal dial being what it is, the visual impression of the Montre 3 is dominated by its movement. With a layout inspired by that of a historical Ferdinand Berthoud pocket watch, the caliber FB-BTC.FC features a prominent chain and fusée mechanism that supplies 50 hours of consistent energy to the escapement.

The latter is arguably the star of the show, featuring a hand made split bi-metallic Guillaume-style balance that self-adjusts for temperature changes the old fashioned way, by expanding and contracting. Against all odds, the Montre 3 is a COSC-certified chronometer, making it almost certainly the first wristwatch with a bi-metallic balance to pass this test under current standards.

For a watch with a nearly seven figure price tag, the value proposition is fairly straightforward. To the roughly 11,000 hours of high-cost Swiss labour required to make each Montre 3, one can factor in a typical luxury margin due an object with this kind of built-in exclusivity. One could argue there’s additional value derived from being associated with the quasi-charitable endeavour that is the Naissance d’une Montre project, which is admirable in its objectives.

The white gold pieces are priced at CHF850,000, but the market will get to set the price for a pièce unique in stainless steel that will go under the hammer at Phillips’ Geneva Watch Auction XXII in November, with part of the proceeds going to a charity dedicated to the preservation of horological know-how (presumably the Time Æon Foundation).

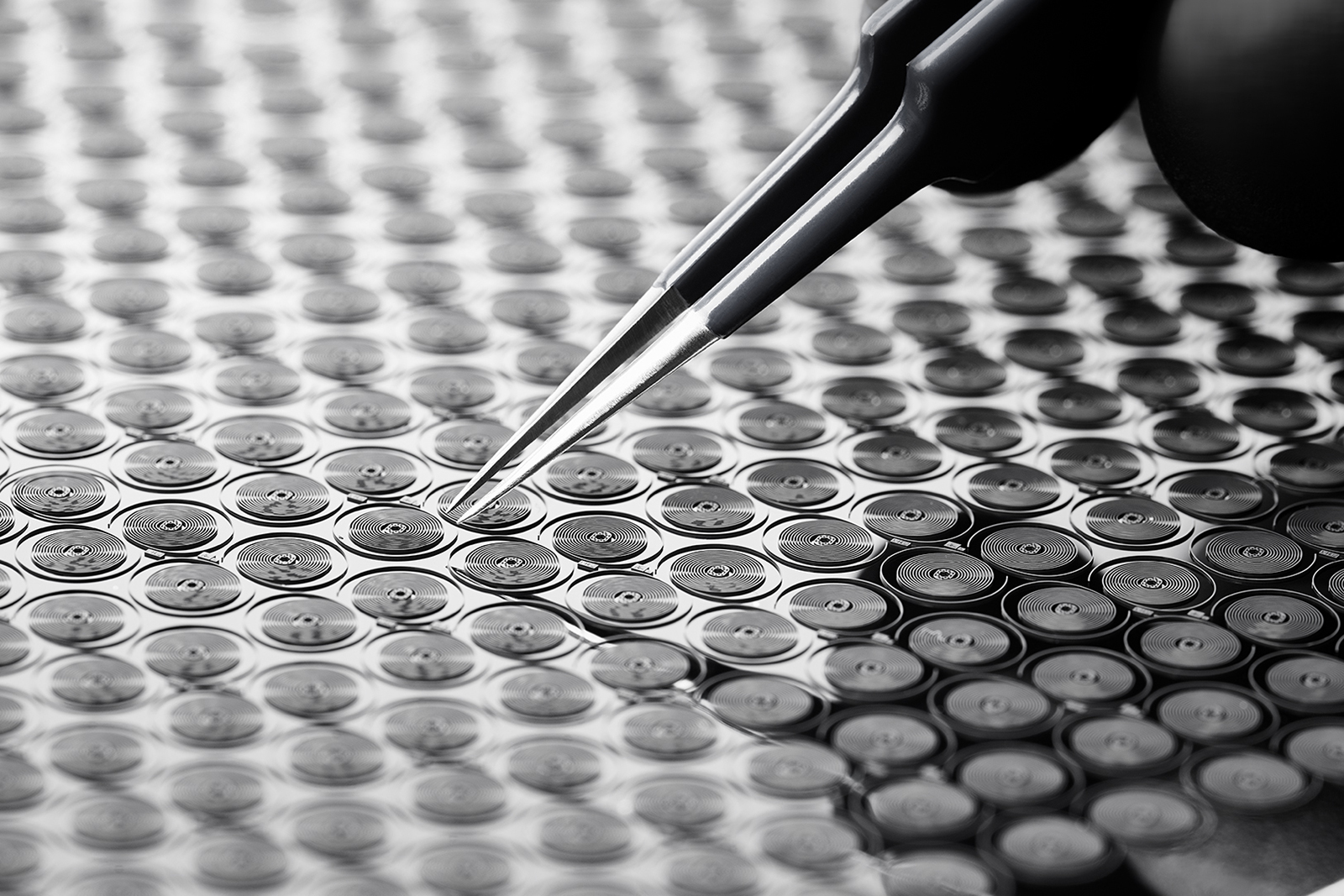

The hour and minute hands during polishing. Image – Ferdinand Berthoud

The birth of a watch

The Naissance d’une Montre project (which translates to English as ‘birth of a watch’) got going in 2009 as a community project to document and transmit endangered watchmaking skills to future generations of artisanal watchmakers. The overarching idea was to create a small series of watches entirely by hand without any computerised assistance, meaning no CNC, wire erosion, LIGA, or any other semi-automated production methods.

The Montre 1 “Montre École” prototype, sold at Christies for close to 1.5 million USD.

The project is overseen by the Time Æon Foundation, and doesn’t belong to any single brand. The first project, Montre 1, debuted in 2012 and was a series of 10 watches made by Michel Boulanger under the guidance of Greubel Forsey and Philippe Dufour.

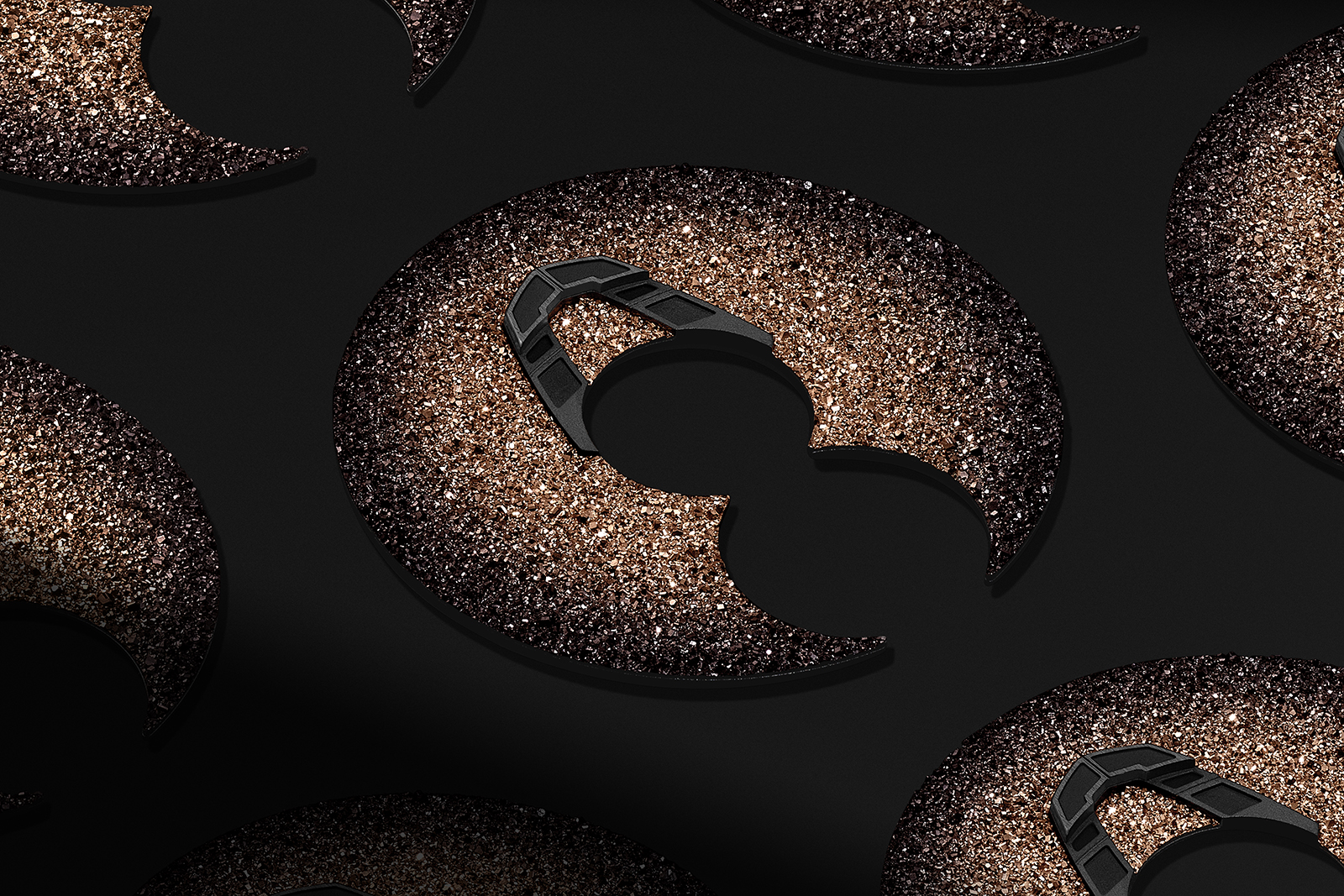

The second project, Montre 2, commenced in 2015. These watches were made by Dominique Buser and Cyrano Devanthey, again with the help of Greubel Forsey, but with additional guidance from Urwerk, which explains the futuristic design.

Alongside the 2019 launch of the Montre 2, it was announced that FB would take the lead on the third chapter and the watch would apply the Naissance d’une Montre approach to a watch with a chain and fusée mechanism.

Six years later, coinciding with the brand’s 10th anniversary, Ferdinand Berthoud has delivered. Unlike the Montre 1 and Montre 2 that were the result of collaborations, the Montre 3 is a wholly FB creation.

The meaning of ‘hand made’

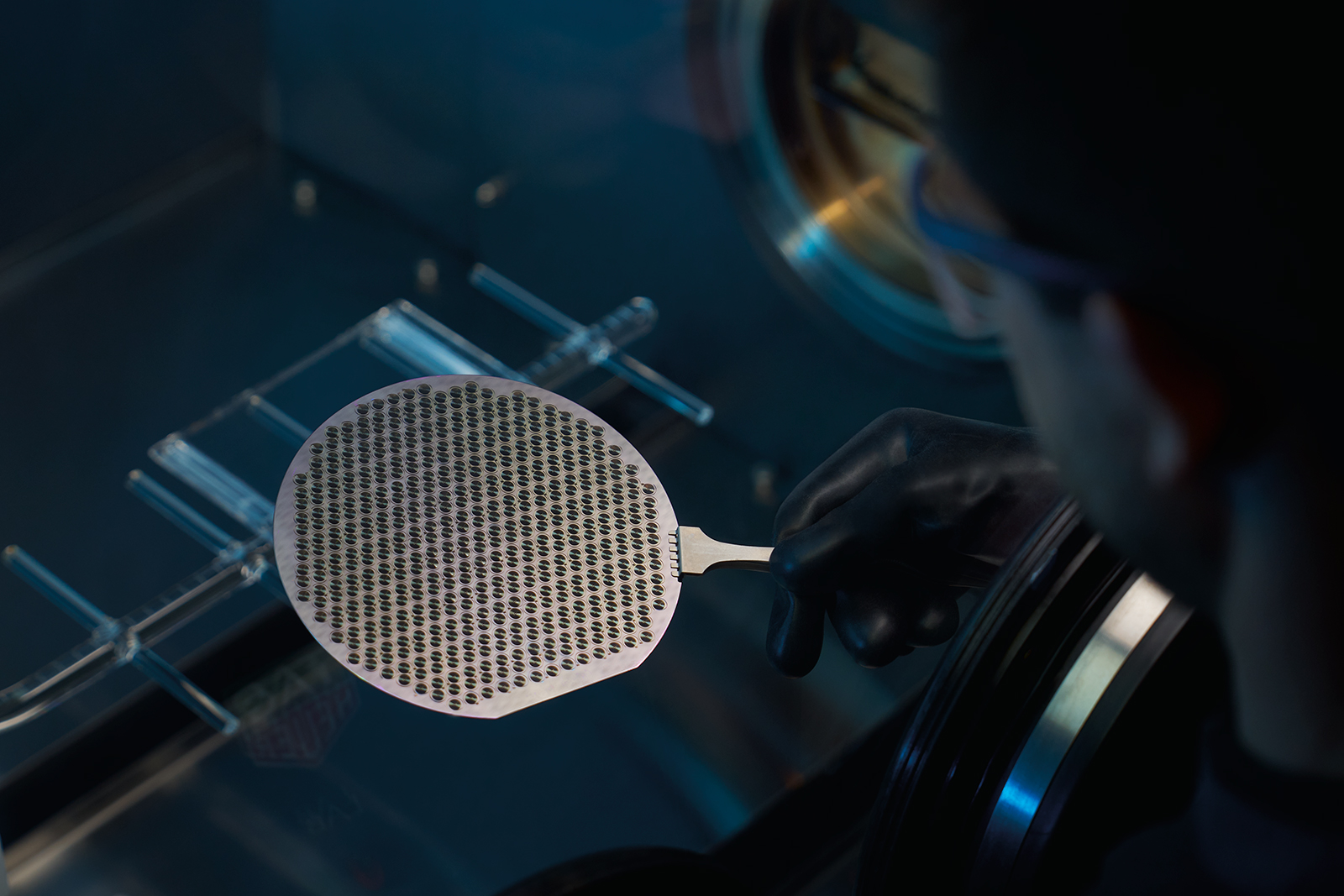

There are few phrases I try to avoid as much as ‘hand made’ because things rarely are. But the Montre 3’s raison d’être is the fact that it is hand made, so it’s worth defining what that means. In short, each of the Montre 3’s 747 individual components were made with hand-operated tools, many of which, like the Schaublin 102 lathe used for the circular components and the SIP jig boring machine used to drill and tap the plates, are more than 60 years old.

This means everything takes a really long time. The hour hand, for example, requires 54 different operations and takes about two days for a watchmaker to cut, polish, and flame-blue its surfaces. In total, the first example of the Montre 3 required close to 11,000 labour hours to produce from start to finish.

Polishing pinion leaves. Image – Ferdinand Berthoud

Polishing the hands. Image – Ferdinand Berthoud

To put this in perspective, George Daniels produced pocket watches at a rate of about 3,000 hours per watch, and Greubel Forsey’s million-dollar Hand Made 1 is known to require about 6,000 hours of work. While the Montre 3 plays it safe with a traditional lever escapement and lacks a tourbillon, the movement is otherwise more elaborate and demanding in its construction than even these vaunted peers.

Subsequent pieces will no doubt benefit from the know-how acquired making the first one, but fact remains the Montre 3 is about as hand made as an object can be. Even the strap and watch box are made with this limitation in mind.

The production of the Montre 3 relies on hand-operated machines. Image – Ferdinand Berthoud

A view through the looking glass at the pinion leaves. Image – Ferdinand Berthoud

The Montre 3 also serves as a useful example of the limits of what can be achieved by hand. The geometries are fairly simple, and the components are are quite bulky; the same is true for other hand made watches.

This takes away nothing from the watch, but serves as a guidepost for enthusiasts to help distinguish the difference between watches made with a lot of CNC and those like the Montre 3 that use only hand-operated tools.

Hand-operated lathes are used to produce all circular components. Image – Ferdinand Berthoud

Even the notches on the crown are cut manually, one by one. Image – Ferdinand Berthoud

Perfectly balanced

Oscillating at a frequency of 21,600 beats per hour, the split bi-metallic Guillaume balance is arguably the stand out feature of the Montre 3, being entirely unique in contemporary watchmaking. Modern watches account for temperature in a very straightforward way, using alloys that are thermally stable.

But it wasn’t always so easy; before the development of Glucydur balance wheels and Nivarox hairsprings in the 1930s, watchmakers would fuse metals with different thermal expansion coefficients, like brass and steel, to create a balance wheel that would expand and contract to compensate for the effects of temperature on the hairspring.

The first bi-metallic compensation balances were developed in France and England around the same time in the late 1700s; Berthoud was quick to see the advantages of this approach and contributed to its later development. The next significant breakthrough occurred in 1899 when Charles-Edouard Guillaume developed Anibal, an alloy with non-linear temperature expansion, that eliminated a thorny problem called middle temperature error.

Middle temperature error was the final frontier of temperature compensation, and tests at the Neuchâtel Observatory confirmed that an Anibal-equipped bi-metallic balance reduced middle temperature error from 1.9 seconds to 0.3 seconds per day; a huge jump in precision. Guillaume later won the Nobel Prize in physics for these developments.

The know-how for making Guillaume balances was lost to time once more advanced alloys made them obsolete, and FB invested a great deal of effort into rediscovering these methods. Given the aims of the Naissance d’une Montre project, I would not have expected the Montre 3 to be chronometer certified and would not have noticed the absence of COSC certification. But the brand’s full name is actually Chronométrie Ferdinand Berthoud; submitting its watches for certification is a matter of principle.

Even so, it’s surprising because the current testing process favours mass-produced high-frequency movements; haute horlogerie calibers tend to fail at higher rates. Making a bi-metallic Guillaume-style balance at this size using manual methods is already impressive; managing to do so with enough precision to rival contemporary chronometers is a major demonstration of skill.

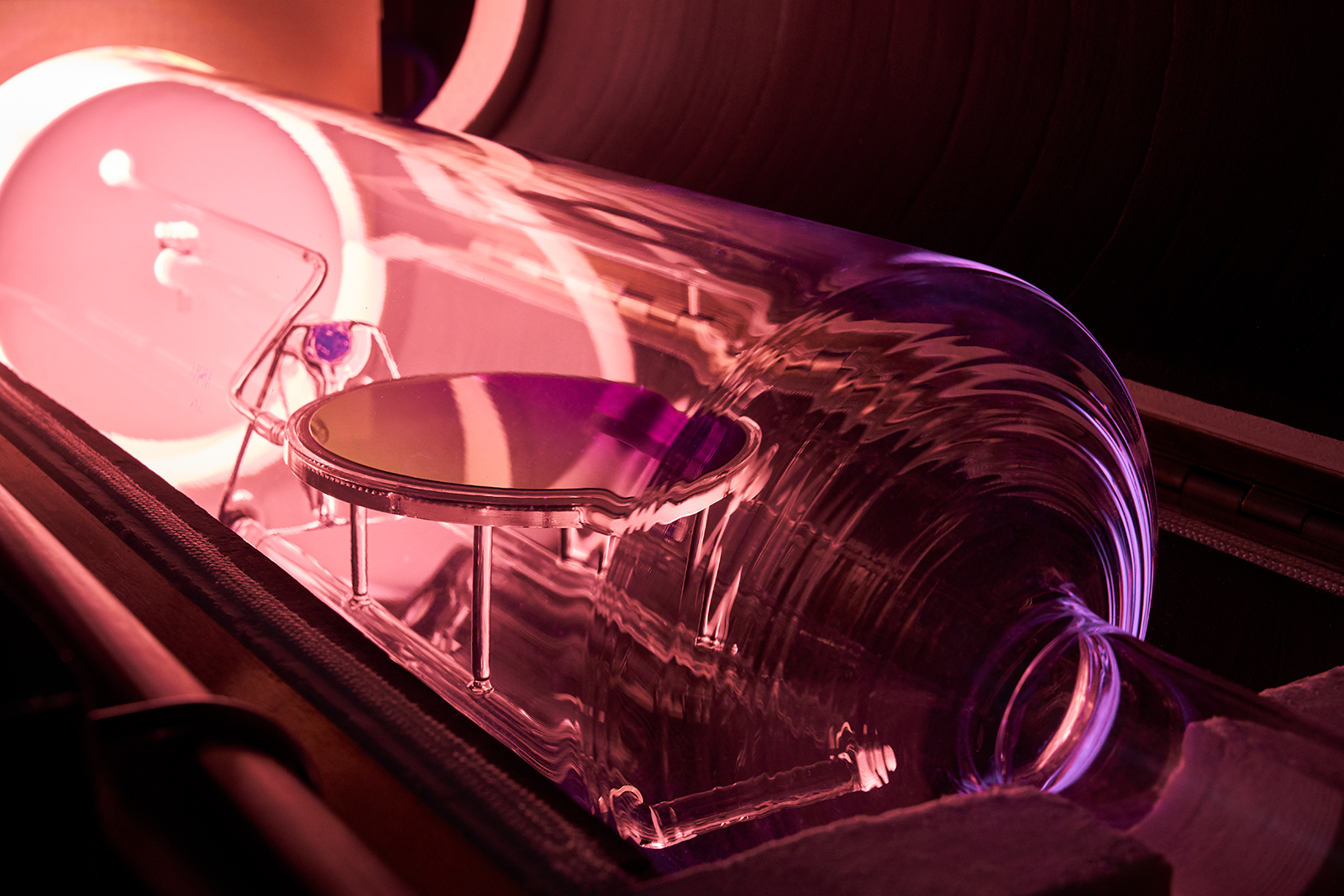

The escapement contains another surprise, which is a set of natural diamond end-stones held in place by hand-made shock absorber springs. This contrasts with the approach taken by watches like the Greubel Forsey Hand Made 2 that use contemporary Kif shock absorbers, and is another way in which the Montre 3 stands apart.

The inverted form and functionality also departs from traditional usage of diamond end-stones; brands like A. Lange & Söhne often use them to embellish their tourbillon watches, but only on the pivot for the tourbillon cage, not the balance staff itself.

With craftsmanship like this, one element stands out as underwhelming: the escape lever itself. While undoubtedly hand made like the rest of the movement, it nonetheless looks like it could be from any other high end watch.

A. Lange & Söhne Datograph Perpetual Tourbillon features diamond end-stones, not for the balance staff, but for the tourbillon pivot.

Links to the past

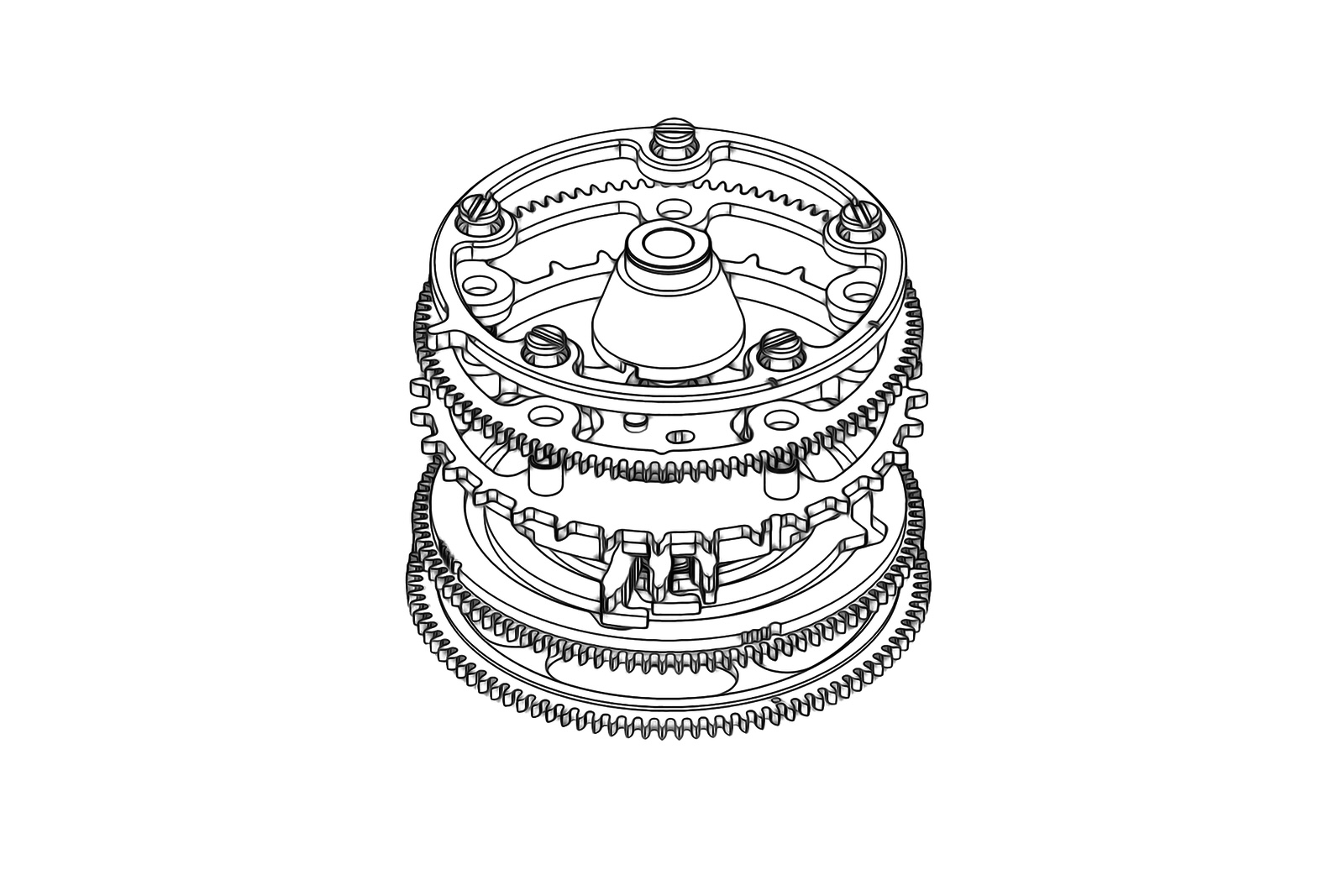

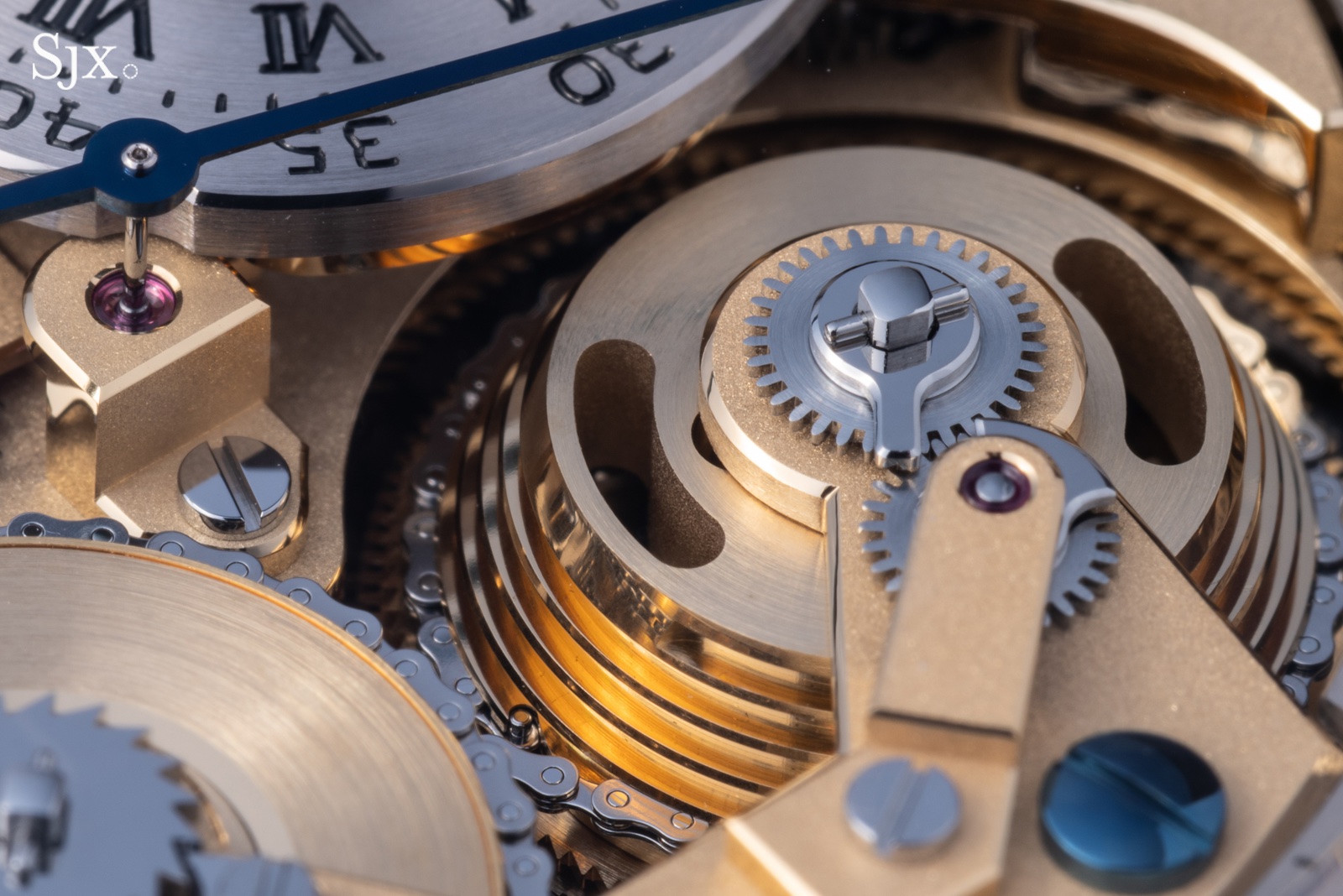

The other significant feature of the Montre 3 is its chain and fusée, which benefits from FB’s decade of experience making watches equipped with this primitive device.

The chain and fusée divides the power source into two components, a mainspring barrel and spiral-cut cone, linked by a miniature chain. At full power, the mainspring pulls on the narrow end of the fusée cone, but as the spring unwinds, the chain slowly coils around progressively wider sections of the cone, increasing mechanical leverage as the tension in the spring decreases.

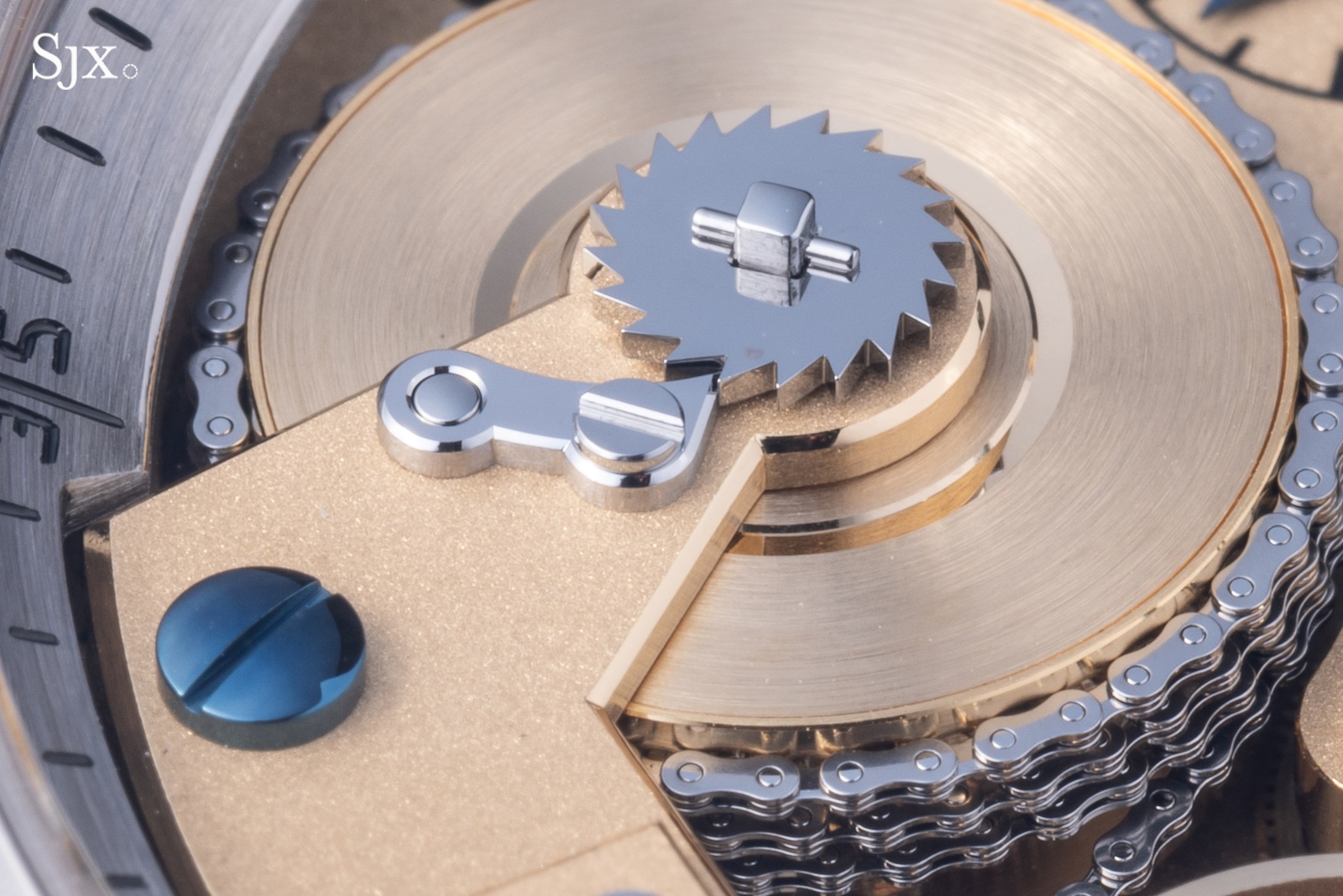

One of the complicated things about this setup is that, unlike ordinary mainspring barrels that are wound in the same direction that they unwind, the chain and fusée must rotate backward during winding, requiring additional complexity to keep the movement ticking while the watch is wound. In the case of the Montre 3, this takes the form of an auxiliary spring with about 30 minutes of power reserve that sits compactly within the fusée cone.

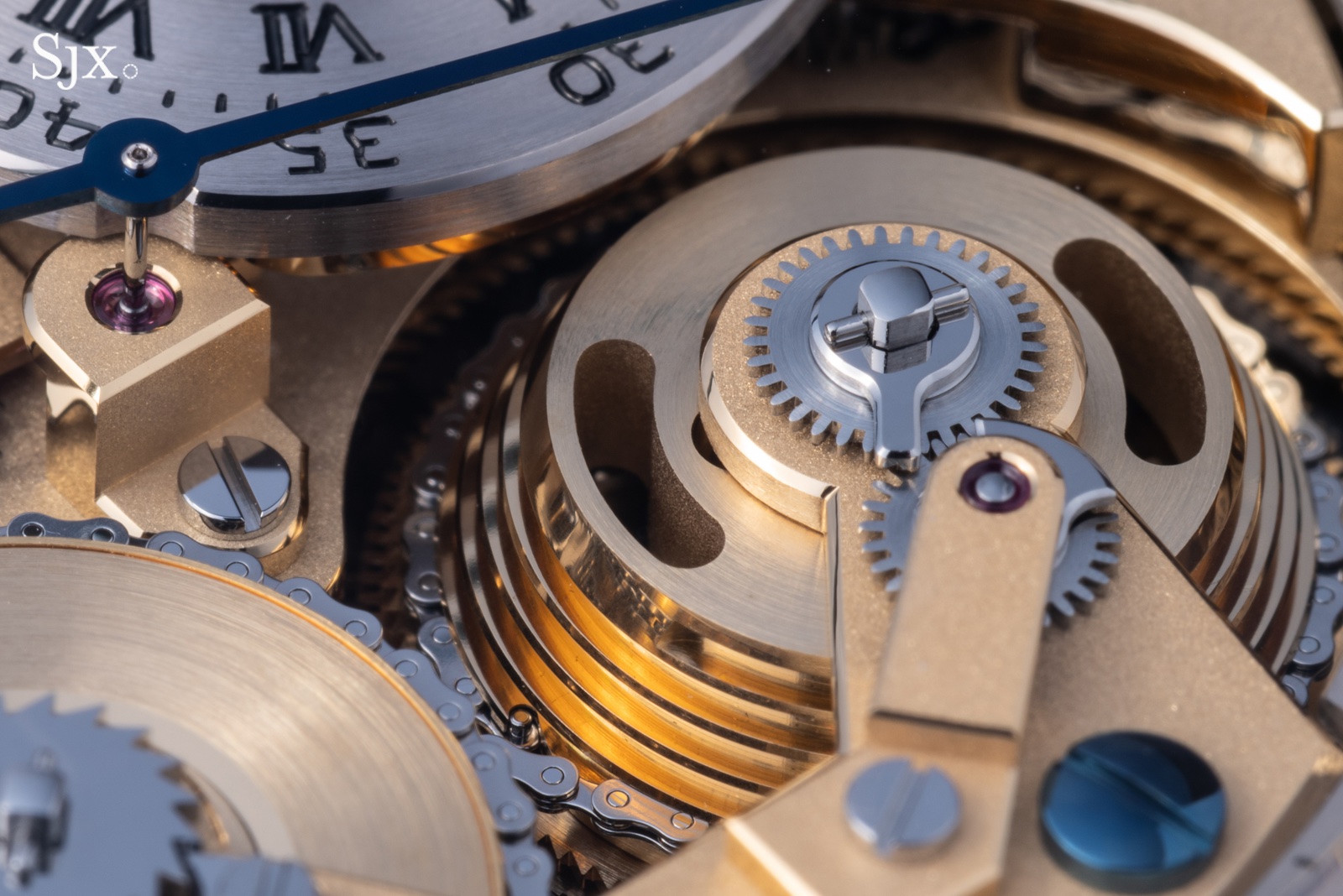

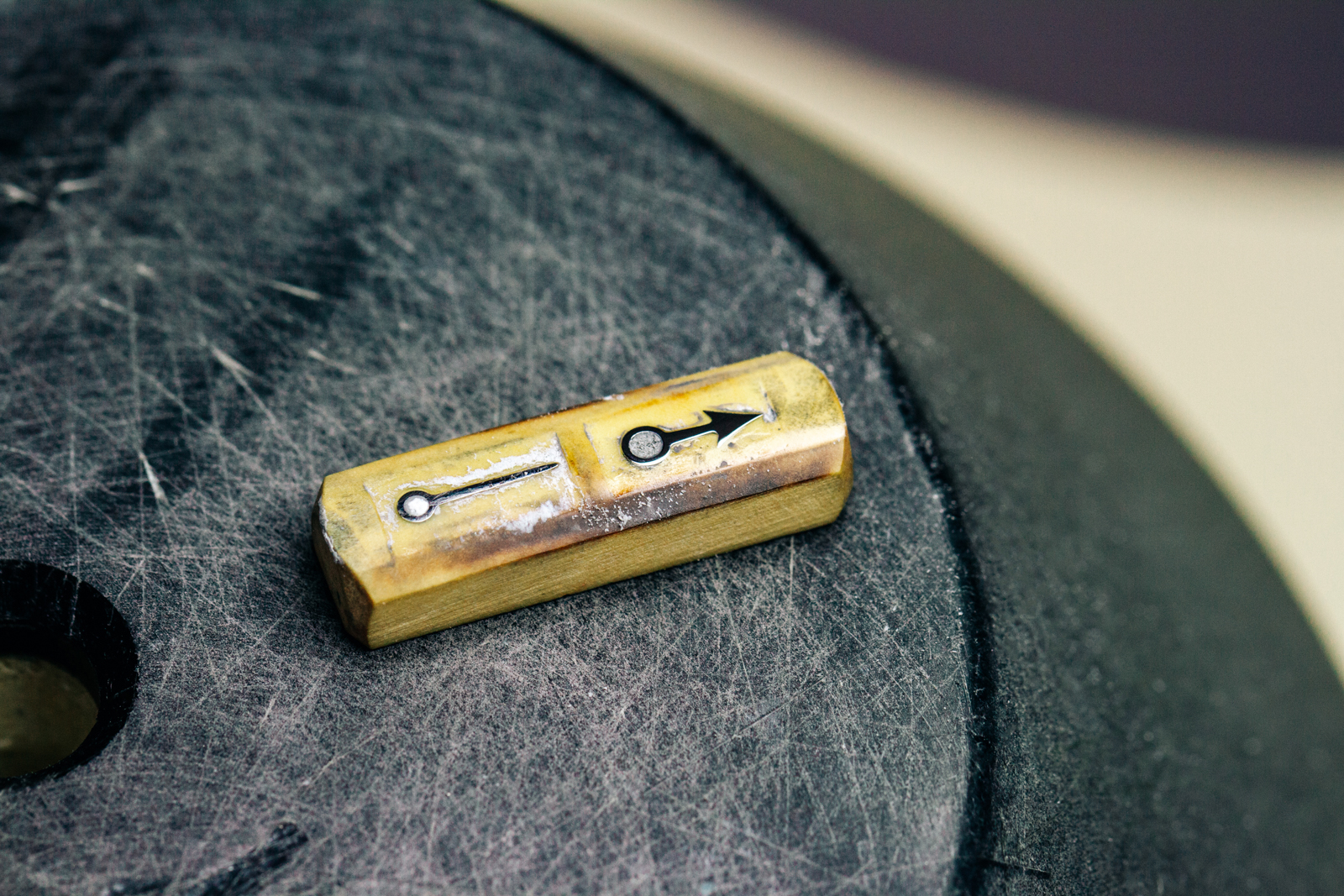

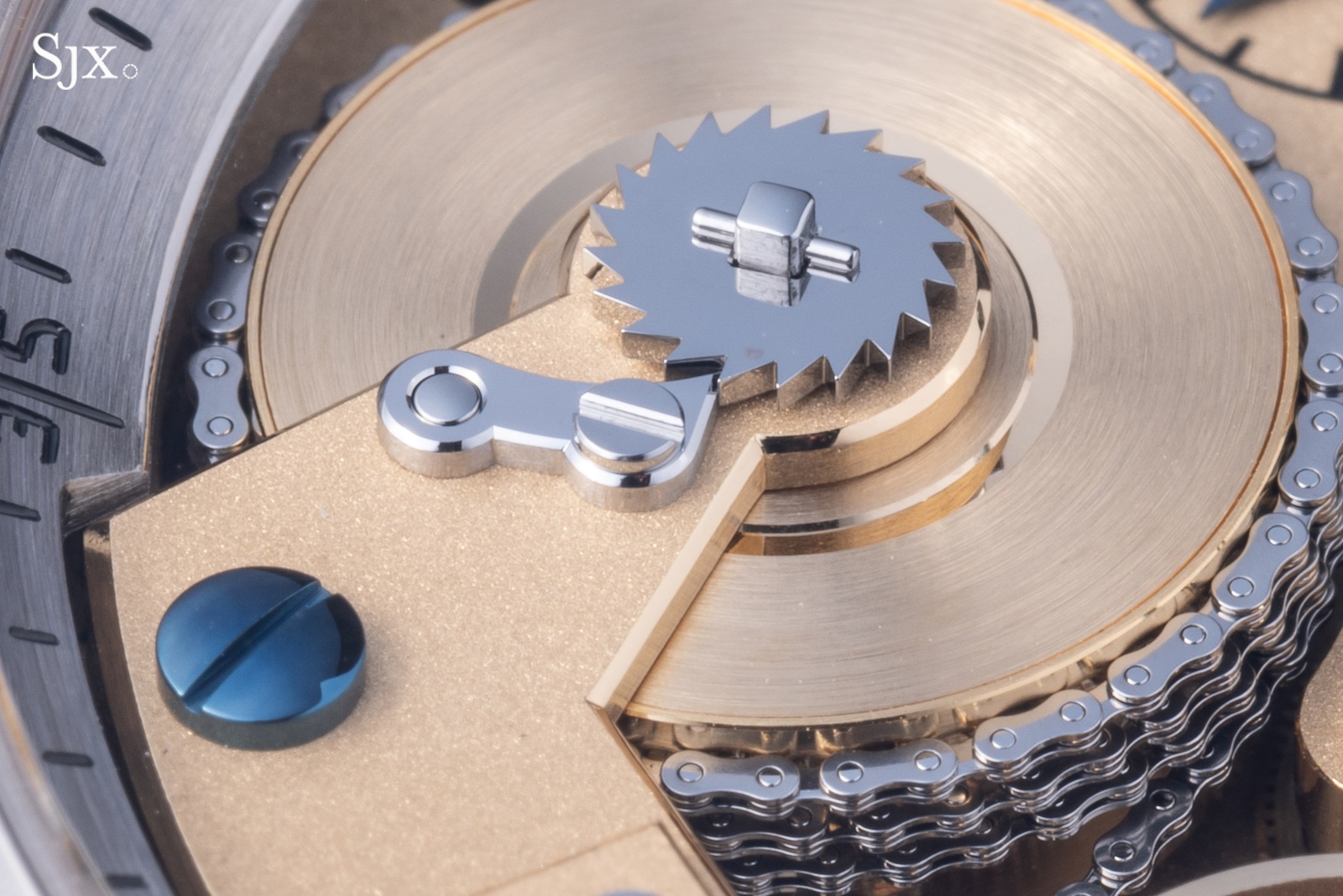

The black polished steel stop work mechanism atop the fusée cone, which contains an auxiliary spring to power the escapement during winding.

We now think of the chain and fusée as a type of constant force mechanism, which it is, but it was developed nearly 500 years ago as an alternative to the hairspring, which had not yet been invented. With the invention of the hairspring and subsequent development of detached escapements, the chain and fusée fell out of favour, and for good reason. The chains were fragile and tedious to make, and due to the incredibly small size of the links, children were often ’employed’ to assemble them.

The first wristwatch to employ a chain and fusée was the groundbreaking A. Lange & Söhne Tourbillon Pour le Mérite that debuted in 1994. A few other brands, namely Breguet, Zenith, Romain Gauthier, and Christoph Claret have dabbled with this gadget, but it hasn’t been taken up more widely for obvious reasons. It’s a bulky, complicated mechanism that, thanks to modern escapements, is largely irrelevant to actual timekeeping.

But why go to all this trouble? In short, it’s sexy and cool and a show of technical prowess. The chain in the Montre 3 is 172 mm in length. Though shorter than the FB1’s epic 285 mm chain, it compares well to the chains employed by Lange and Zenith, which measure about 150 mm and 180 mm, respectively. But unlike these predecessors, each of the Montre 3’s 285 links are made entirely by hand, including 191 pins that are just 0.3 mm in diameter.

The 8.8 mm crown provides a good grip to experience the delightful winding feel.

There’s also another benefit, which is the winding feel. Chain and fusée watches tend to have a very distinctive and satisfying feel to the crown operation, and that’s true with the Montre 3. It’s difficult to describe, but the sensation is characterised by detents that feel especially smooth and robust.

Finishing

Given the theme of this watch, it probably goes without saying that the finishing is done by hand. But it’s worth a quick examination because the details are handled so well.

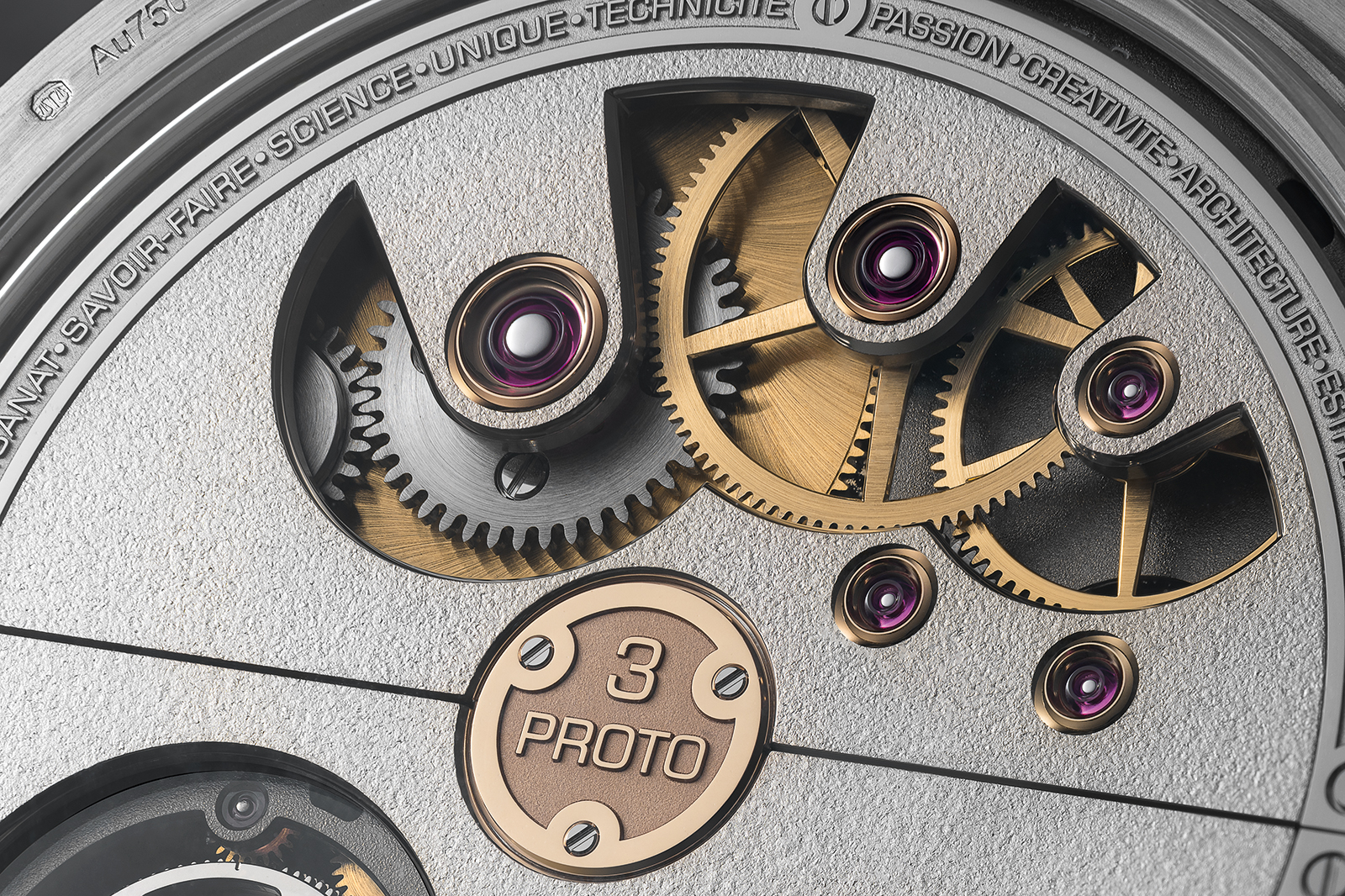

Consistent with the style of Berthoud’s era, the German silver plates and bridges are given a gilded, sandblasted finish with gleaming anglage. The black polished steelwork is peerless, with distortion-free reflections of adjacent components.

Note the perfect inner angles on the steel winding click, and the reflection of the square-cut post in the surface of the click wheel.

Even though sharp inner angles were not part of the French tradition in the time of Berthoud, and were popularised by nineteenth century Swiss watchmakers in the Vallée de Joux, the Montre 3 lives up to contemporary expectations for a watch of this stature. The openings around the lower pivots of the chain and fusée are a joy to behold, and even the steel winding click is extravagantly finished.

Both the main dial and the flange for the seconds are made of solid white gold and free-hand engraved and lacquered. The movement is also engraved with flowing script that translates as, “Dedicated to time, the great teacher.” This is said to be a maxim of Louis Berthoud, Ferdinand’s nephew who took over the business after his death and who was a renowned watchmaker in his own right. For a watch that takes so much time to make, this inscription is fitting.

Free-hand engraving of the solid white gold dial. Image – Ferdinand Berthoud

Accessories

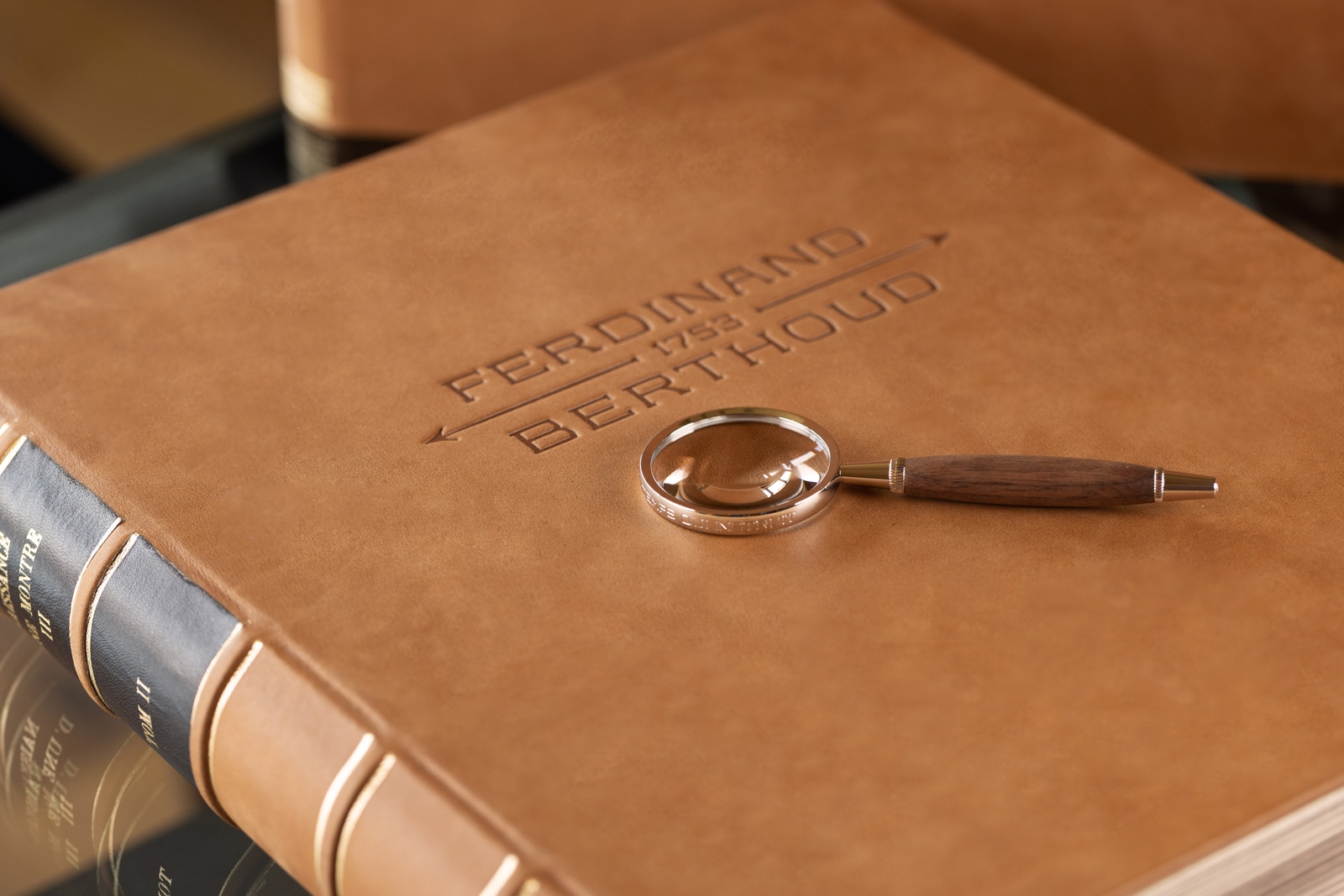

I rarely feel the need to mention the accessories that accompany a watch, but in this case it’s worth looking at how far FB has gone in its commitment to the aims of the Naissance d’une Montre project. As you may have now guessed, the watch box is entirely hand made with antique equipment.

There are actually two boxes, each designed to look like an old book, inspired by the volumes published by Berthoud in his time. The boxes are made of wood, covered in leather, and embossed. The first houses the watch, and the second contains the supporting documentation including a USB stick with the full details of production.

The hand made presentation box. Image – Ferdinand Berthoud

Both presentation boxes are made using antique binding equipment. Image – Ferdinand Berthoud

Closing thoughts

The most refined and impressive Naissance d’une Montre project to-date, the Montre 3 is a testament to the vision of brand president Karl-Friedrich Scheufele. When initially announced in 2019, the stated aim of Montre 3 was to apply the hand made concept to a watch with a chain and fusée mechanism, which was already a big undertaking. The addition of a cut bi-metallic balance suggests to me that this project came from the heart, not just the mind.

There’s a remarkable coherence to the Montre 3 that expresses itself in improbable ways. Take the Guillaume balance, for example. Not only was Berthoud himself one of the early pioneers of bi-metallic temperature compensation, but both he and Charles-Edouard Guillaume were born in the same small Swiss town of Val-de-Travers, 134 years apart. If Val-de-Travers sounds familiar, that’s because it’s where the Montre 3 and all other Ferdinand Berthoud watches are produced today.

The movement engraving translates as “Dedicated to time, the great teacher.”

Key Facts and Price

Ferdinand Berthoud Naissance d’une Montre 3

Ref. FB 4BTC.1

Diameter: 44.3 mm

Thickness: 13 mm

Material: 18k white gold (piece unique in steel)

Crystal: Sapphire

Water resistance: 30 m

Movement: FB-BTC.FC

Functions: Hours, minutes, seconds, power reserve indicator, with chain and fusée

Winding: Hand-wind

Frequency: 21,600 beats per hour (3 Hz)

Power reserve: 50 hours

Strap: Alligator with matching pin buckle

Limited edition: 10 pieces in 18k white gold; 1 in stainless steel

Availability: At boutiques and retailers

Price:

White gold – CHF850,000 excluding taxes

Steel – to be auctioned for charity at Phillips’ The Geneva Watch Auction: XXII on November 8-9, 2025 at the Hotel President Wilson

For more, visit Ferdinandberthoud.ch.

Back to top.