In-Depth: Ferdinand Berthoud FB RS Régulateur Squelette

A deservedly closer look at a fascinating variant.

Having launched one of the best watches of 2020 with the spectacularly decorated Chronomètre FB 2RE, Ferdinand Berthoud (FB) returned to its very first model this year, remaking the FB 1 by bestowing upon it an open-worked movement accompanied by more contemporary styling.

The result is the Ferdinand Berthoud FB RS – short for Régulateur Squelette, or “regulator skeleton”, which tidily sums up the time display format as well as the movement. Like the original FB 1, the new model has both a tourbillon as well as a chain and fusée.

Notably, the FB RS is actually two models but equipped with the same movement, the FB-T.FC-RS. One is an octagonal case in sandblasted steel, the decidedly modern FB 1RS.6, while the other is the more conventional FB 2RS.2 in a round case of polished 18k rose gold.

The FB-T.FC-RS

While the two versions are quite different in terms of style, both share a similarly large diameter – resulting from the calibre within that boasts exemplary construction and finishing.

The FB 1RS.6 in steel

The FB 2RS.2 in gold

Initial thoughts

FB’s watches are best described as big and chunky – too big mostly – with equipped with exceptional movements. And the models with a tourbillon are especially big.

Because of the their size, FB tourbillons tended to have a wide, empty expanse on the dial (which was dressed up with italic script in recent models). In contrast, the FB RS does away with all that empty real estate by uncovering the mechanics below. It’s still a big watch, but even more beautiful.

The open-worked dial on the rose gold model

And on the steel version

That makes the FB RS is an excellent variant of the original, as the partially open-worked dial exposes much of the gear train originally hidden, leaving plenty to admire. In fact, the FB RS is clearly the best version of the FB tourbillon to date, possessing tremendous aesthetic appeal.

Choosing between the two versions of the FB RS is difficult. The steel model is more appealing for its lightness and colours, but the octagonal case remains an acquired taste that’s tough to acquire – and it’s matched by a narrow strap that doesn’t help. That said, the shape is the brand’s signature case design, having been inspired by an 18th century marine chronometer made by Ferdinand Berthoud himself.

The round case, on the other hand, is conventional in form and more easily digestible, though its lugs remain oddly stubby. It size means that the watch is a mass of polished rose gold, making it both heavy and extremely shiny.

At the same time, the external elements of the case, namely the screws that secure the crown guards and lugs, stand out more on the rose gold version. They give the case a slightly fussy appearance, leaving it seeming a bit over-designed.

But regardless of the case style, the movement inside is truly first class.

Lots of screws on the case

Given the FB RS is a relatively thick watch, much of its movement’s depth deserves to be appreciated through the open-worked dial, especially since the movement has a architectural construction reminiscent of Greubel Forsey.

Tastefully done without excess, the open-working exposes just enough of the intricate going train and tourbillon to make it interesting, while avoiding revealing too much such that the bland bits are on show.

The rest of the dial remains intact to avoid visual chaos, with the upper half containing all the necessary timekeeping scales that are nicely legible despite the unorthodox layout.

In fact, even with the exposed movement on the front, there is still much to admire on the back, which shows off the fusée and chain mechanism that delivers constant force to the going train.

A closer inspection of the movement reveals that almost every last bit of real estate within has been meaningfully used up, which further enhances the movement’s depth. There is no wasted space inside the watch, making the extremely chunky case entirely forgivable.

The movements in the steel and gold versions are slightly different

With the movement in the gold version having a bit more of a vintage flavour

And of course, the finishing is almost second to none. It’s an exemplary masterclass of consistent anglage done by hand with abundant inward angles, and neat graining or frosting across all surfaces. The decoration truly deserves to be explored further with a loupe or in closeup photos.

As a result, the big price tag that companies the watch – starting from CHF235,000 in steel – is eminently reasonable as such things go, especially considering the high standard of finishing and the unique, panoramic movement architecture.

Movement first, then the case

Strictly speaking, the FB RS is a limited edition of 20 movements that will be delivered in either of the case styles, round and gold or octagonal and steel. As a result, the number made of each case style will depend on demand.

Though both versions share the same calibre, a few movement components are treated differently to match the case. Most notably, the movement in the steel case gets the fusée and barrel plated in rhodium, while its gold counterpart will have them plated in gold.

Both cases have a diameter of 44 mm, making them truly large watches. Thanks to the massive cases, the FB RS is not something you forget on the wrist.

The crown is cleanly machined with a well-defined knurling, with a black ceramic inlay bearing the FB logo

The crystal is tall enough that it distorts the view at certain angles

They are also chunky due to their thickness – the steel case is 13.95 mm, while the gold case even exceeds that at 14.26 mm. Part of the thickness is due to the domed sapphire crystal that extends above the bezel.

Though the difference in between between the two is less than half a millimetre, the rose gold version looks and feels noticeable thicker, primarily due to the tall, polished bezel that is concave, accentuating the domed crystal. And the bright colour of the rose gold case also makes it more prominent.

But the size of the watch is a price worth paying for the movement within. It’s an appropriately huge calibre that deserves a deeper dive to appreciate of the mechanics, design considerations, and finishing.

The folding clasp is suitably large to balance the weight of the watch

Hours, minutes – exposed, segregated

Mechanically, the FB RS is a minor variant of the earlier model. The only thing that sets it apart is the regulator-style display. While the original model had a sub-dial for hours and minutes at 12 o’clock, the FB RS retains only the minute hand in that position, and instead relocates the hours display to two o’clock.

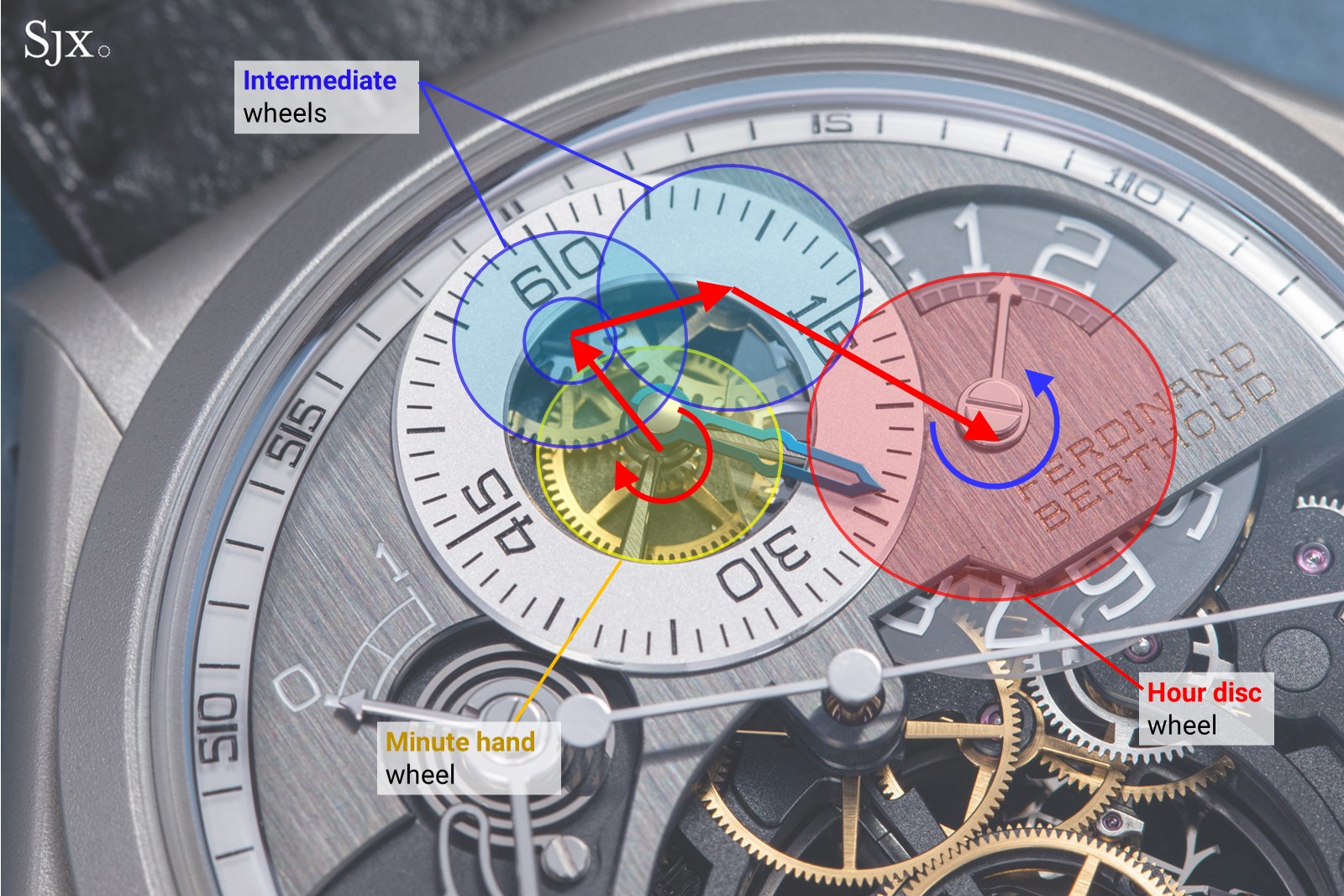

Instead of a typical hour hand, however, a clear sapphire disc rotates counter clockwise to indicate the hours. The disc is visible thought a curved opening on the dial, with a fixed, arrow-shaped hand pointing to the current hour.

The hour disc is continuously driven, meaning it turns at a constant rate all the time. It is not a jumping hour display – which would’ve been a real bonus. But its function is understandable, given the space limitations in an already densely-constructed movement.

The hours disc has machine-engraved numerals filled in white lacquer

The time displays on both versions are identical

The choice of a transparent hour disc is a modern touch. That mix of different materials, both new and old, evokes Greubel Forsey’s approach to aesthetics and construction.

And the clear disc is also a sensible design choice. Its large diameter means the disc extends into the open-worked minute dial to its left and gear train below, so the disc would obstruct those components had it been opaque.

The opening within the sub-dial allows a glimpse of the motion works underneath, including at bottom left the additional gear train responsible for the relocated hour display.

This additional gear trait gives away a peculiarity of the movement: the convoluted setup of the time display going train. Given the complexity of redirecting the gear train to indicate the time in a 12 o’clock sub-dial, as was the case on the original model, repositioning the hours off to the side makes it even more complicated. We will explore this in greater detail later on.

The minute sub-dial at 12 is open-worked, with a pair of tiny struts that support the minute hand pinion. Despite their size, the two little arms are finely finished and display perfect anglage.

Tourbillon, front and back

The bottom half of the dial is naturally an important element of the movement – it showcases the large tourbillon, which is unusual in two respects.

As the tourbillon was originally designed to be viewed from the back, since the original model had a closed dial, it is the rear of the tourbillon cage that’s visible on the dial of the FB RS. As a result of the inverted tourbillon as seen from the front, the carriage also rotates counter-clockwise on the dial (but clockwise when observed from the back).

The tourbillon bridge on the front is architectural in form and style

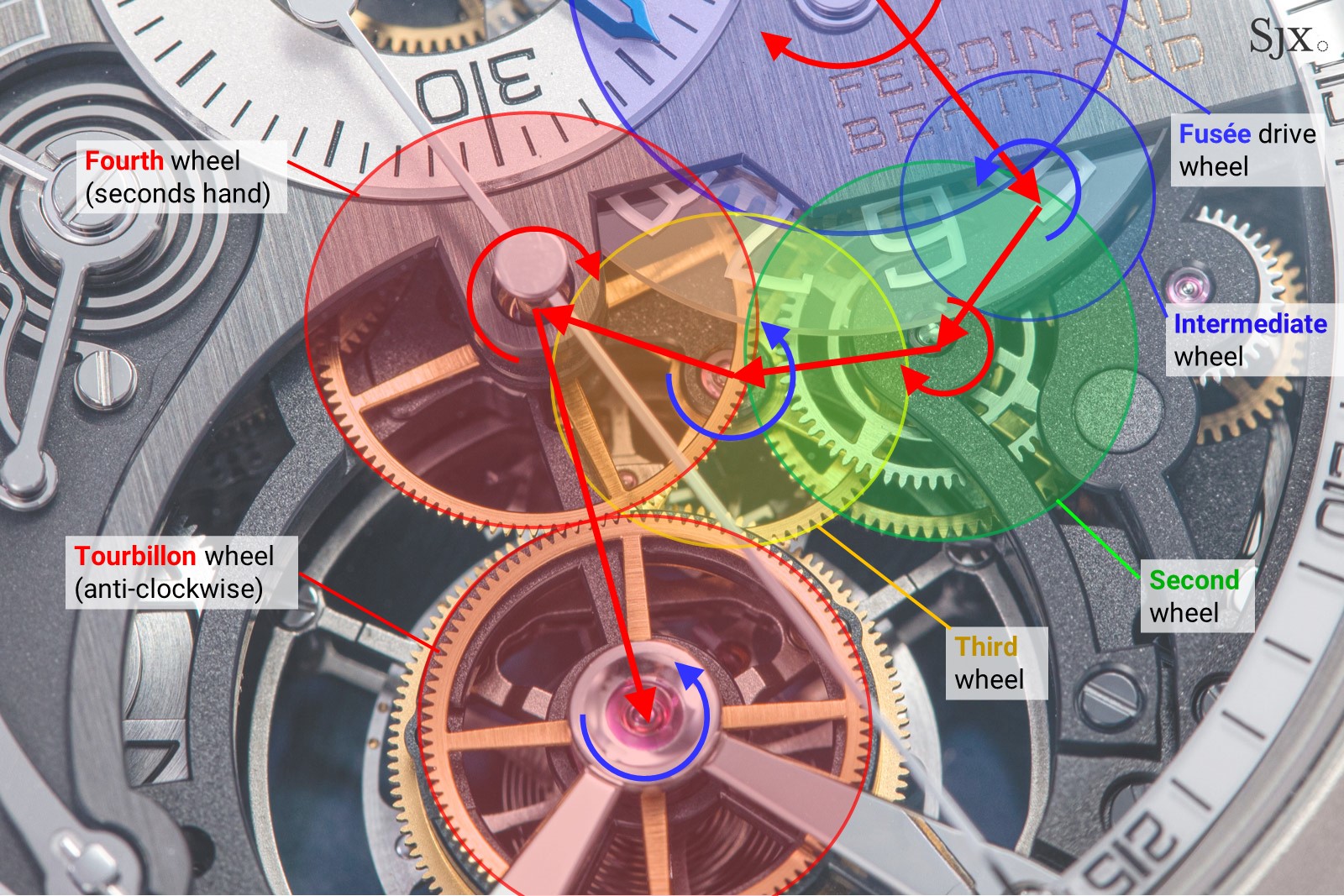

The second has to do with how it is set up: the tourbillon wheel is directly driven by a large fourth wheel at the centre of the watch, the same wheel to which the sweep seconds hand is mounted. This fourth wheel is directly driven by the movement’s going train.

In contrast, a conventional tourbillon design would have no central seconds or central fourth wheel, but instead rely on a seconds hand fixed to the tourbillon cage.

One particular element that speaks to the fine attention to detail in the construction of the movement is the perfect meshing between the fourth and tourbillon wheel – the spokes of each wheel point directly towards each other as the wheels turn. As wristwatch gear trains rarely have a 1:1 ratio in the meshing of their wheels, this is a sign of intentional care put into the movement’s construction in order for a flawless presentation.

The spokes of the fourth and tourbillon wheel align as they mesh, revealing the thought put into the cutting of the teeth of each while, in order to ensure perfect relative position of the spokes

Once again the spokes align

To maximise the view of the tourbillon, there is not a conventional linear bridge on the front. Instead the pivot of the tourbillon cage is secured by a black-polished bridge that forms a wide “V”. Particular care is paid to the finish of this bridge, as it is the centrepiece of the dial in terms of finishing.

Its arms are inclined – sloping downwards away from the tourbillon pivot – and each arm catches the light alternately as the watch moves. With the addition of the anglage along its edges and a highly polished, bowl-shaped countersink at its centre, the tourbillon bridge is a beautiful, jewel-like component in steel.

Both the bridges and main plate below the tourbillon bridge are finely frosted and then coated black, creating strong contrast against the coloured parts such as the gilded wheels, jewels, and polished steel parts. But the dark coating does mute the polished bevelling of the bridges, which is a shame since it is all beautifully done.

Contrasting surface finishes – frosted and circular grained

The off-centre conundrum

Surprisingly, the off-centred sub-dial for the time is a big deal in technical terms. Since most of the gear train is exposed, this allows for a good discussion of the consequences of a regulator-style time display, where the hours, minutes, and seconds are indicated on separate axes.

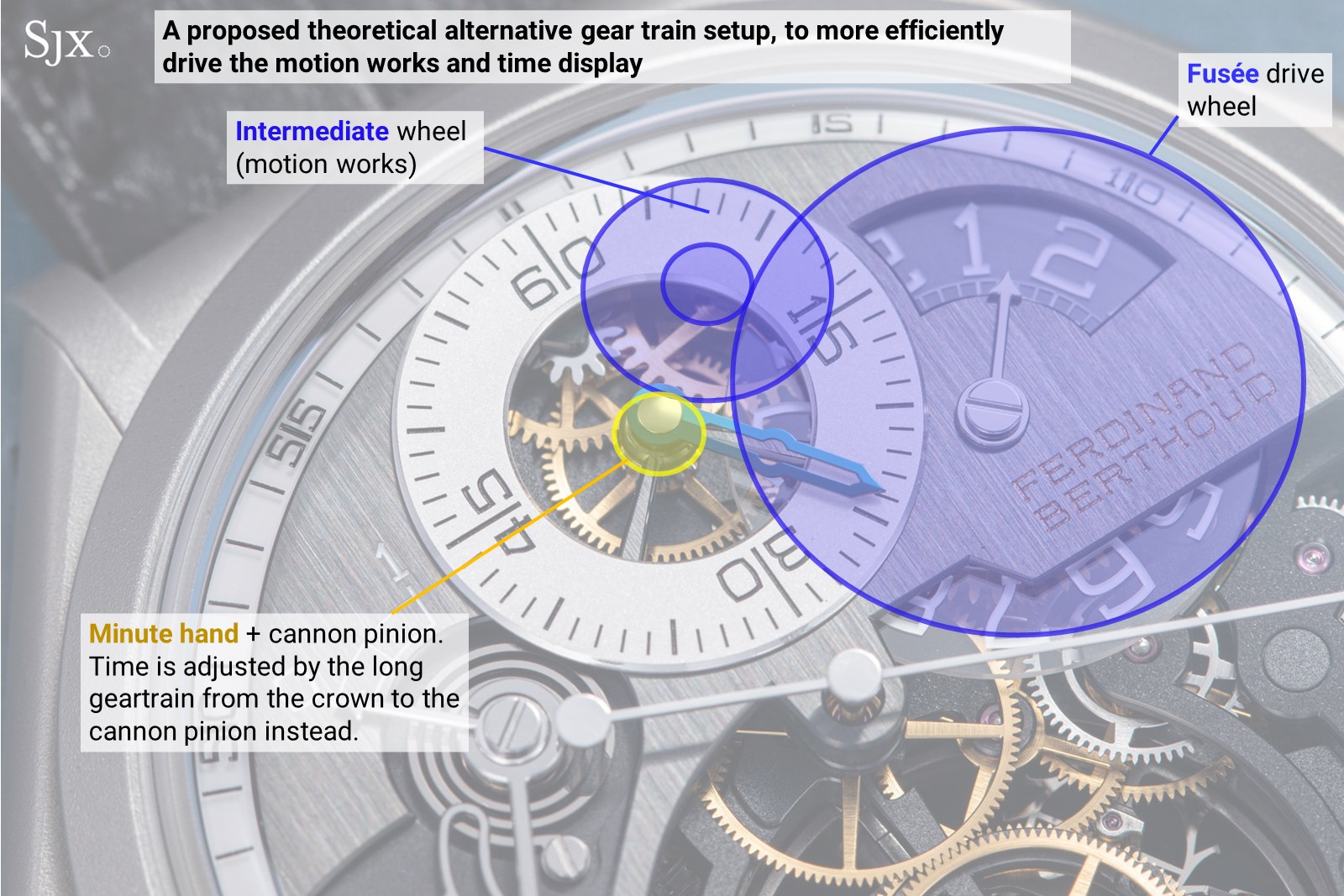

An unfortunate consequence of the off-centre dial is the convoluted gear train. Relocating the minutes away from the centre necessitates a long, snaking gear train of three intermediate wheels to drive the minute hand in the 12 o’clock sub-dial. This is arguably the sole technical compromise of the movement, simply because there’s no space in the upper half of the movement, which is occupied by the fusée and barrel, leaving no room for a directly-driven hand.

As a rule of thumb, the number of wheels in an auxiliary gear train should be minimised for optimal efficiency. Every additional wheel adds potential play and backlash between gears, resulting in the possibility of a minute hand that sets imprecisely. In other words, you turn the crown to set the time but the minute hand takes a while to start moving.

When this issue becomes critical due to the construction, the solution is usually anti-backlash gears – either a stacked pair of spring-loaded gears, or by gears with springs integrated into each tooth that are fabricated with modern, lithography techniques.

But the FB RS makes its even more complex, exacerbated the potential problems with the regulator-style display that results in the off-centre hour disc. The gear train is already a modification on the original FB1 to accommodate the eccentric minutes, and now demands another set of intermediate wheels to drive the hour disc.

In total, there are six intermediate wheels between the second wheel and the hour disc, which increases the potential of gear backlash even further. This would be most prominent when setting the time, where the minute hand and hour disc misalign relative to each other. As a result, adjustment of the meshing of the wheels and clearances between them are now critical.

In retrospect, a possible alternative to the layout in the FB RS movement is an auxiliary second wheel located at 12 o’clock, directly driven by the fusée driving wheel. This would eliminate the complex auxiliary gear train, reducing the backlash within the train. That said, another set of wheels would be need for the keyless works to reach the cannon pinion at 12 o’clock to set the time.

But the fact that the movement deals with the complexity of the additional going trains, while having perfectly crisp winding and setting is a tangible testament to the splendid finishing and adjustment executed during assembly. The resulting tolerances are correct, perhaps even perfect, and an achievement only possible and viable on a small scale within a high-end watchmaking workshop.

Another interesting consideration of the regulator display is the location of the slipping clutch for time adjustment. In a conventional movement, the time display is driven by the cannon pinion, which in turn is friction-fit to the centre wheel of the going train. When adjusting the time via the crown, the hands move and the cannon pinion slips, all without damaging the going train.

While this is hidden on a regular watch, the slipping clutch can be seen in the FB RS. Thanks to the open-worked dial, its equivalent of the slipping clutch can be seen at three o’clock, in the form of rhodium-plated wheels that are connected to the crown to facilitate time setting. Distinguishing these wheels with rhodium plating – as opposed to gilding for the other gears – is an ideal method of colour-coding wheels by function. And it something that the wearer can easily appreciate when setting the time and seeing the wheel turn.

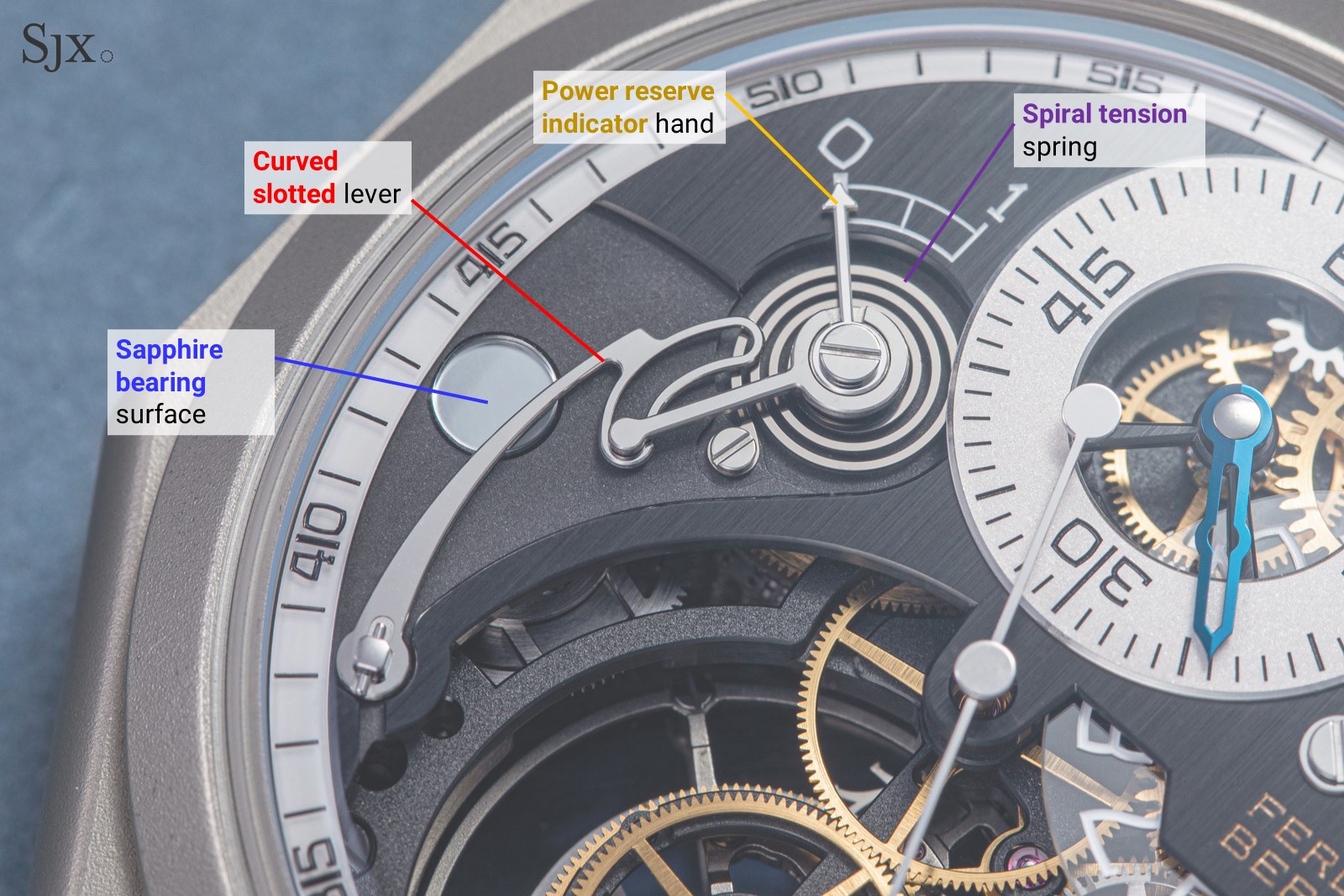

Old-school power reserve

Meanwhile, visible at ten o’clock is the power reserve indicator. It consists of a spiral-shaped, steel spring, which provides tension to the indicator hand, eliminating play or drift in the hand.

This tension is necessary due to the curved, slotted lever used to move the hand – a needlessly elaborate and thoroughly beautiful setup intended to showcase black polishing and anglage. Even the indicator hand has anglage along its length and tip, complete with inward angles at the arrowhead.

Even the base of the lever is an anachronistic detail that brings to mind classical watchmaking – a square arbor with a pin to hold the lever in place. Historically, this was often used for high torque components such as mainspring barrel arbor, as unlike a round shaft, the square shaft can transmit high torque to the connected wheel without slipping.

The reverse landscape

Ironically, there are less mechanical details visible on the rear of the watch, since most of the view is dominated by a trio of large, circular elements – the fusée, barrel, and a large tourbillon cage. That said, the bridges that flank the tourbillon are skeletonised, with the right bridge giving a good view of the cone mechanism of the power reserve, which is hidden in the original movement.

The power reserve indicator is not merely anachronistic in presentation, its mechanics are distinctly 18th century. Unlike modern movement that uses a differential gear to show power reserve, the FB RS utilises a cone and feeler.

It is a traditional solution consisting of a cone that slides up and down the threads of a vertical screw – winding the barrel raises the cone, while letting the mainspring unwind run gradually lowers the cone. A tensioned mechanical feeler touches the edge of the cone – the feeler is furthest away from the vertical screw with a fully-wound barrel, and vice versa – which rotates the power reserve lever as seen on the dial.

The cone (at right), with the feeler reflected on its sloping side

This feeler-and-cone setup requires significant vertical height, which the FB RS movement has in spades, but is mechanically simple. A consequence of the fusée and chain is that the barrel unwinds in one direction, but has to be wound the opposite way to rewind the chain. Therefore, no complex differential gearing is needed for the power reserve indicator, and the direction of the barrel rotation simply drives the cone up and down the screw.

The feeler (left) and cone. Image – Ferdinand Berthoud

The chain and fusée

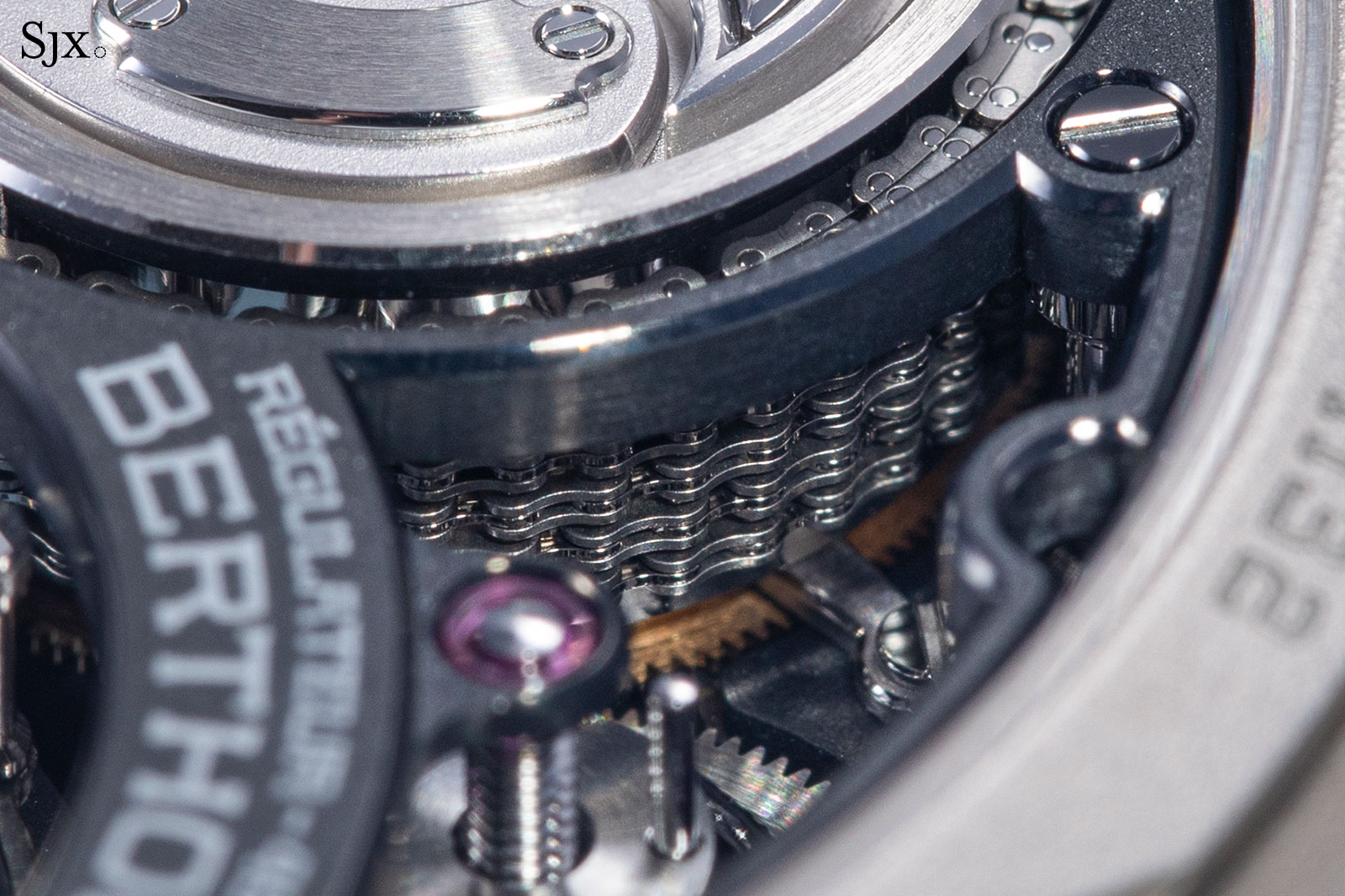

The old-school power reserve indicator complements the mechanical centrepiece of the FB RS (though it’s a tossup between this and the tourbillon), which is the fusée and chain mechanism. Visible through the display case back, the chain and fusée are of a “hanging” or “floating” construction, which means there are no bridges to support the fusée and barrels, leaving them anchored only at their base – resulting in an unobstructed view of the well-finished components.

A tiered cone, the fusée has a chain wrapped around it. One end of the chain is connected to the fusée. The other end of the chain is hitched to the barrel, which “pulls” on the chain as the mainspring unwinds, unwrapping the chain from around the fusée. This rotates the fusée which in turn, drives the movement. The fusée works like the sprockets of a bicycle chain drive, relying on the principle of leverage to ensure the torque supplied by the barrel is constant, from a mainspring fully-wound all the way down to fully unwound.

The fusée and chain of the FB RS. The chain links between the fusée and barrel in a figure eight shape, resulting in two sharp outward angles of the bridges in the middle

The titular chain made up of tiny, riveted links

However, the chain and fusée are accompanied by a fundamental problem – winding the watch. On its face, the set up means that when barrel is empty, the fusée has to be wound backwards to rewind the chain. This will cause the movement to be driven backwards, which would stop the movement or even drive the escapement in reverse.

To solve this, the FB RS, much like other fusée and chain watches, incorporates a differential gear into the winding train. The planetary gears of the differential are visible within the ratchet wheel on the fusée. Typically called on to mechanically “split” power delivery without locking up the mechanism, differential gears are also found in automobiles, where they allow the left and right driven wheels to spin at different speeds when making a turn.

The differential is cleverly configured such that when the watch is running normally, the barrel powers the movement via the chain “pulling” the fusée, while the ratchet wheel is locked and stationary due to the click. When the watch is wound, the ratchet wheel turns the fusée backward to rewind the barrel, but at the same time still applies torque in the same direction that powers the going train.

This means that in theory, winding the watch while it is running should have relatively minimal impact to the going train, as the movement is supplied with torque from turning the ratchet wheel via the crown, despite the fusée and barrel wound backwards. It is an unavoidable mechanically complex solution to a seemingly innocuous problem inherent to all fusée and chain watches. The equivalent mechanical solution for clocks are known as “maintaining power” mechanisms, which ensures the clock continues ticking while their weights are lifted for winding.

The chain visible is through a porthole in the side of the case on both versions

The gilded barrel and fusee of the rose gold model

Maltese stop and go

Meanwhile, exposed on the barrel is a Maltese cross stop-work mechanism. It serves multiple purposes. For one, it ensures that the mainspring is not used at its extreme ends, either overwound or fully unwound, which is when the torque delivered varies the most and would thus affect the movement’s timekeeping.

The Maltese cross stop-work is more prominent on the gold model due to the colour contrast

Second, the stop-work prevents the chain from excessively wrapping around the fusée when the mainspring is fully wound, which would be disastrous as that might cause the chain to disconnect from the top of the fusée.

The Maltese cross has six lobes on it – corresponding to six full turns of the barrel to fully wind the mainspring. Correspondingly, the chain wraps around the barrel six times as the mainspring runs down, which can also be observed via the transparent window on the case at ten o’clock.

More layers of the chain around the barrel indicates the mainspring is running down

A massive tourbillon

In contrast to the dial, the case back naturally provides a clearer view of the tourbillon, and deservedly so as it is exquisitely constructed. In my opinion, this is one of the most beautiful tourbillons on the market, one replete with countless exceptional details.

The tourbillon is identical in both versions

The cage and balance wheel have fine, thin spokes that give it an airy appearance, while visually projecting a reassuring sensation of fine, delicate detail that makes the spokes appear longer than they are.

Not to mention the elaborate construction – the titanium tourbillon cage has three spokes with well-defined, complex profiles that have precise anglage. The angles in the bevelling are not sloppily rounded or uneven in width, despite being made of titanium, which is harder to finish than steel.

The use of pillars and screws to secure the two halves of the cage together is a traditional touch that further adds to the elaborate construction, which would have otherwise been a single, machined part

The well-defined shape of the tri-lobed tourbillon cage, with barely any unevenness despite the delicately thin spokes

Even the balance wheel is aesthetically beautiful – four gold weights are used to regulate the free-sprung balance wheel design. The weights have a polished, domed profile, transforming what is often rudimentary and functional into an element that is visually attractive and even decorative.

To top it all off, the hairspring of course is formed into an overcoil for concentric “breathing” and better isochronism. This naturally pairs well with the constant force supplied by the fusée and chain.

One of the round gold weights is visible just over the escape wheel

Another pleasing detail: the pair of oblong, gold counterweights screwed to the rim of the tourbillon cage for poising, with one visible above. The weights serve to balance the weight of the escapement on the opposite end of the rim.

In short, the tourbillon is beautifully done and possesses a delicate appearance that embodies fine watchmaking. None of the components appear off the shelf or industrially made – as it ought to be, for decorating the components of the tourbillon easily make up a majority of the cost of production.

But there’s one nitpick – and this is splitting hairs – which is the pallet fork and its bridge. The two could have been black polished to enable them to stand out even more, as with the pallet fork found in the FB 2RE.

The pallet fork and bridge of the tourbillon have a brushed finish, which would look extraordinary with a black polish instead

The black polished pallet fork and remontoir arms of the FB 2RE, for comparison

But that is merely a trifle. Because if it hasn’t been made clear already, the overall finishing of the FB RS is beyond reproach. One reason for that – besides the brand owner’s passion for fine watchmaking – is because the watchmakers who finish the movement parts rely on a higher-than-average magnification of 6.7 times.

The high-powered magnification means the result speaks for itself – the remaining pictures prove the point.

The plaques, Maltese cross and pivot-jewel cock are circular grained to match the barrel

Even the edges of the tiny plaques and Maltese cross lobes have mirror-polished anglage

Notice the rim of the barrel’s top having a perfect mirror reflection of the chain underneath

The diminutive click and clickspring, which are also well-finished

Sharp, well-defined inner angles of the black-polished tourbillon cock

Concluding thoughts

The FB RS was clearly conceived for connoisseurs on many levels. One is mechanical: the desirable mechanisms within that mimic the marine chronometers of yesteryear and achieve superior timekeeping. Another is decorative – the finishing is just that good.

One criticism that can be made is whether all this was necessary or even excessive – combining a fusée and chain for constant force, along with a tourbillon to even out positional errors, is perhaps excessive from a theoretical perspective.

But honestly, matter it does not. The intrigue of combining various mechanisms for the sake of itself sometimes yields beauty – and this is the case here. The skeletonisation that reveals the tasteful choice of component colours and finishing goes a long way in presenting a watch that is paradoxically modern-looking but mechanically anachronistic.

It would be interesting to see whether the FB 2RE would also be given the same treatment in the future, as that is an equally brilliant offering for anyone who wants everything that Ferdinand Berthoud can do – fine construction and finishing – without a tourbillon.

Key Facts and Price

Ferdinand Berthoud FB RS ‘Régulateur Squelette’

Ref. FB 1RS.6 (octogonal, steel)

Ref. FB 2RS.2 (round, rose gold)

Diameter: 44 mm

Thickness: 13.95 mm (octogonal); 14.26 mm (round)

Material: Steel (octogonal); 18k rose gold (rround)

Crystal: Sapphire

Water resistance: 30 m

Movement: FB-T.FC.RS

Functions: Hours, minutes, and seconds in regulator display, power reserve indicator, tourbillon with chain and fusée

Winding: Hand-wind

Frequency: 21,600 beats per hour (3 Hz)

Power reserve: 53 hours

Strap: Alligator with folding clasp

Limited edition: 20 in total

Availability: At boutiques and retailers

Price:

Octogonal, steel – CHF235,000; or 344,000 Singapore dollars

Round, gold – CHF244,000; or 357,000 Singapore dollars

For more, visit Ferdinandberthoud.ch.

Back to top.