The Plan-les-Ouates district of Geneva is well-known for its concentration of watchmaking facilities, earning it the nickname “Plan-les-Watch”. But the standout structure is arguably the Vacheron Constantin (VC) manufacture, which houses both management functions and production under one roof – or more specifically, under one curving metal skin that wraps over the top of the building from east to west.

The area’s other prominent residents include Rolex, Patek Philippe, and Piaget, but you can also find numerous other brands like Frederique Constant, Harry Winston, and Laurent Ferrier clustered together in what feels like a large office park.

“Plan-les-Watch” is where most of the actual watchmaking in Geneva gets done, since most brands have relocated their production facilities to the suburbs over time, leaving FP Journe as the only industrial operation in the city’s historic center. And it is here that power is expressed through architecture, from the imposing black glass facade of the Rolex building to the superyacht-like decks that wrap around the Patek Philippe manufacture.

The reception at the manufacture. Image – Vacheron Constantin

Completed in 2005 to celebrate VC’s 250th anniversary, the Vacheron Constantin building was designed by Bernard Tschumi Architects as a single building. A second wing was then added by the same firm in 2014, increasing both production space and staff amenities.

A key emphasis of the building is lighting, with expansive glass walls on the north and south sides, and courtyards and skylights to bring natural light to interior spaces in a controlled way. The watchmaking operations, for example, are oriented to face north, to create ideal conditions for finishing and assembly.

Understanding the manufacture

The Geneva manufacture is home to about 750 employees spanning numerous functions. The facility is capable of producing between 25,000 and 35,000 watches per year, meaning the production ratio is very similar to that of nearby rival Patek Philippe.

Almost all aspects of VC’s production happen in this building, including the complete production of all in-house movements, and several unusual operations like hairspring production, gem-setting, engraving, guillochage, enamelling, and restoration.

What isn’t done in-house? Cases and most dials are made elsewhere, and may come from in-group suppliers like Donze Baume, for cases, or third-parties like Les Cadraniers de Genève for certain dials, like that of “The Berkley”, the recent grand complication pocket watch. Components for VC’s third-party movements like the cal. 1326 are also made elsewhere, mostly by in-group suppliers like ValFleurier.

One of the exceptionally large and complex dials of the Berkley, which is double sided

The science of watchmaking

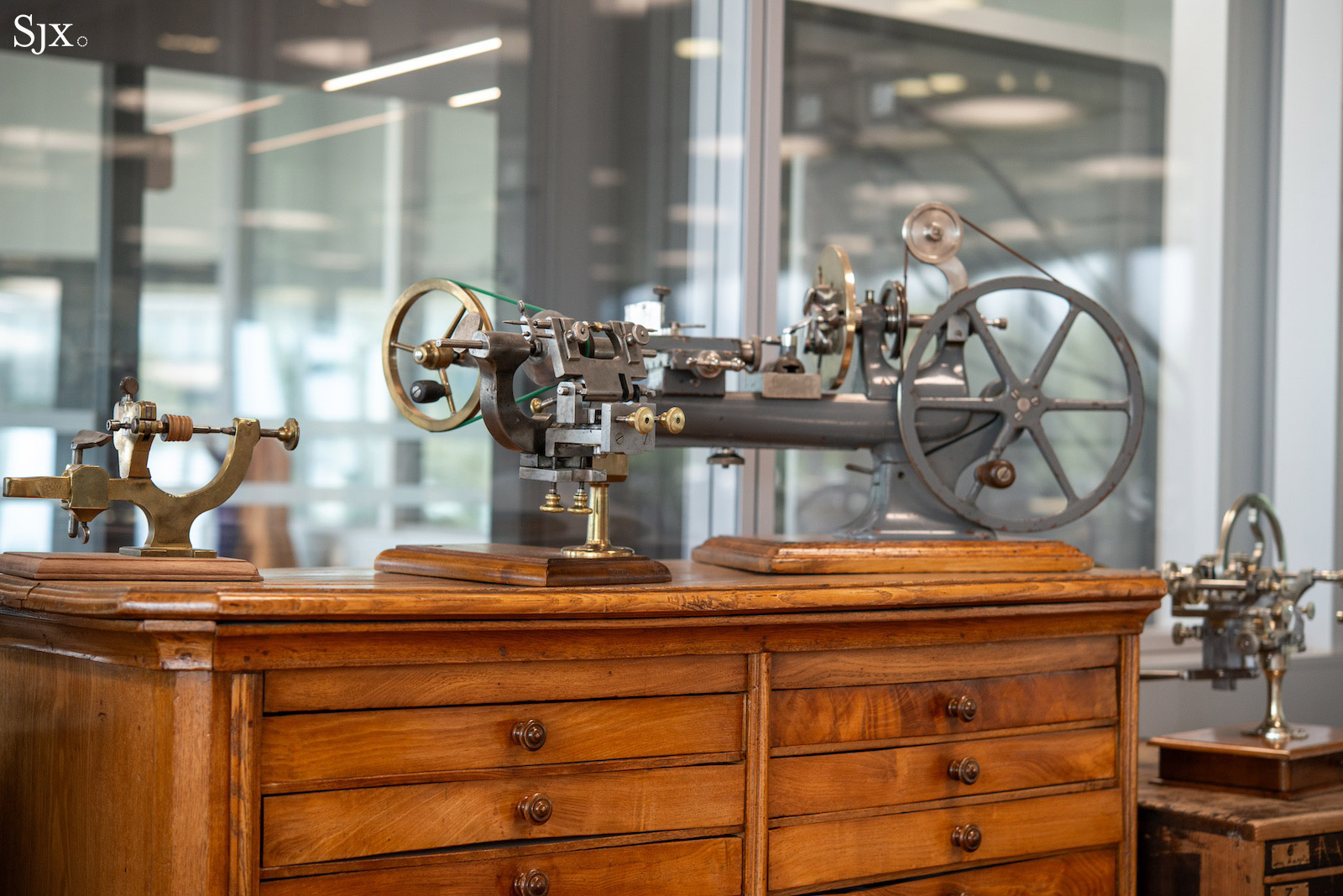

Given the brand’s current standing and reputation for complications and decoration, it’s easy to forget that VC was one of the pioneers of mechanised watch production. One of the most significant events in the brand’s history, and in the watch industry more broadly, was Georges-Auguste Leschot’s development of pantograph milling in the 1840s.

Leschot was the brand’s technical director at the time, and this novel application of a pantograph was a breakthrough that enabled the systematic production of nearly identical components for the first time. This development was one of the first major technological advances that made the idea of interchangeable parts seem like more than just a pipe dream.

While early pantographs were simple machines guided by hand, it’s easy to see their influence on modern day production methods. After all, a modern CNC machine is a bit like an automated pantograph, but instead of tracing a physical object, it traces a digital one.

The machine room

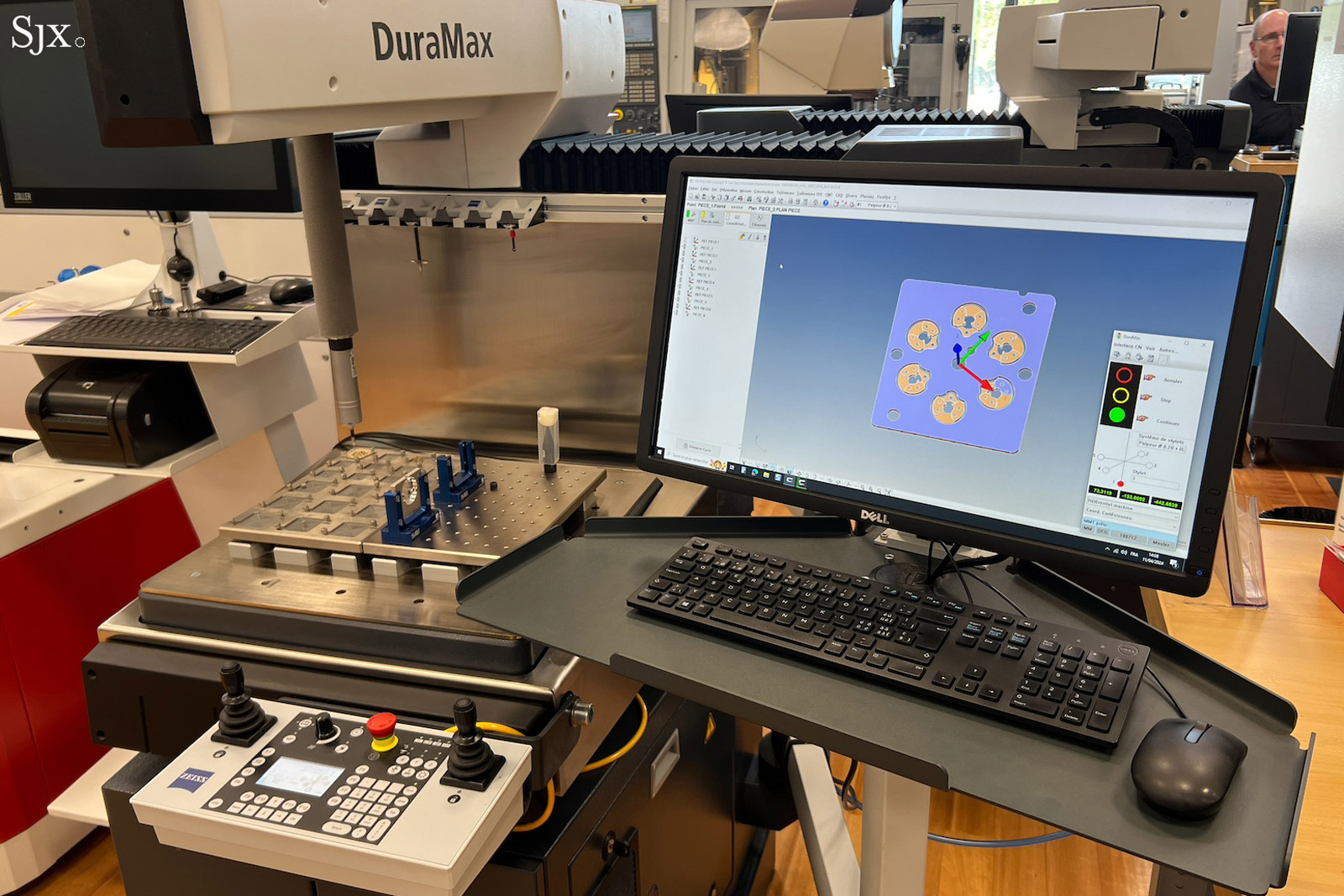

Thus it was fitting that the first stop on the tour was the machine room, where rods of metal are fabricated into movement plates, wheels, barrels, and other parts using large semi-automated CNC and spark erosion machines. Functionally, the machine room is much like that of any other high-end watch manufacture.

But having visited other machine rooms in the past, I was struck by the immaculate conditions at VC. These noisy operations are typically relegated to basements that are packed full of machines, but at VC this work is done at ground level, which gives these rooms plenty of natural light.

Second, there is an almost luxurious amount of open space, which is one of the signals that maximising output is not the primary goal.

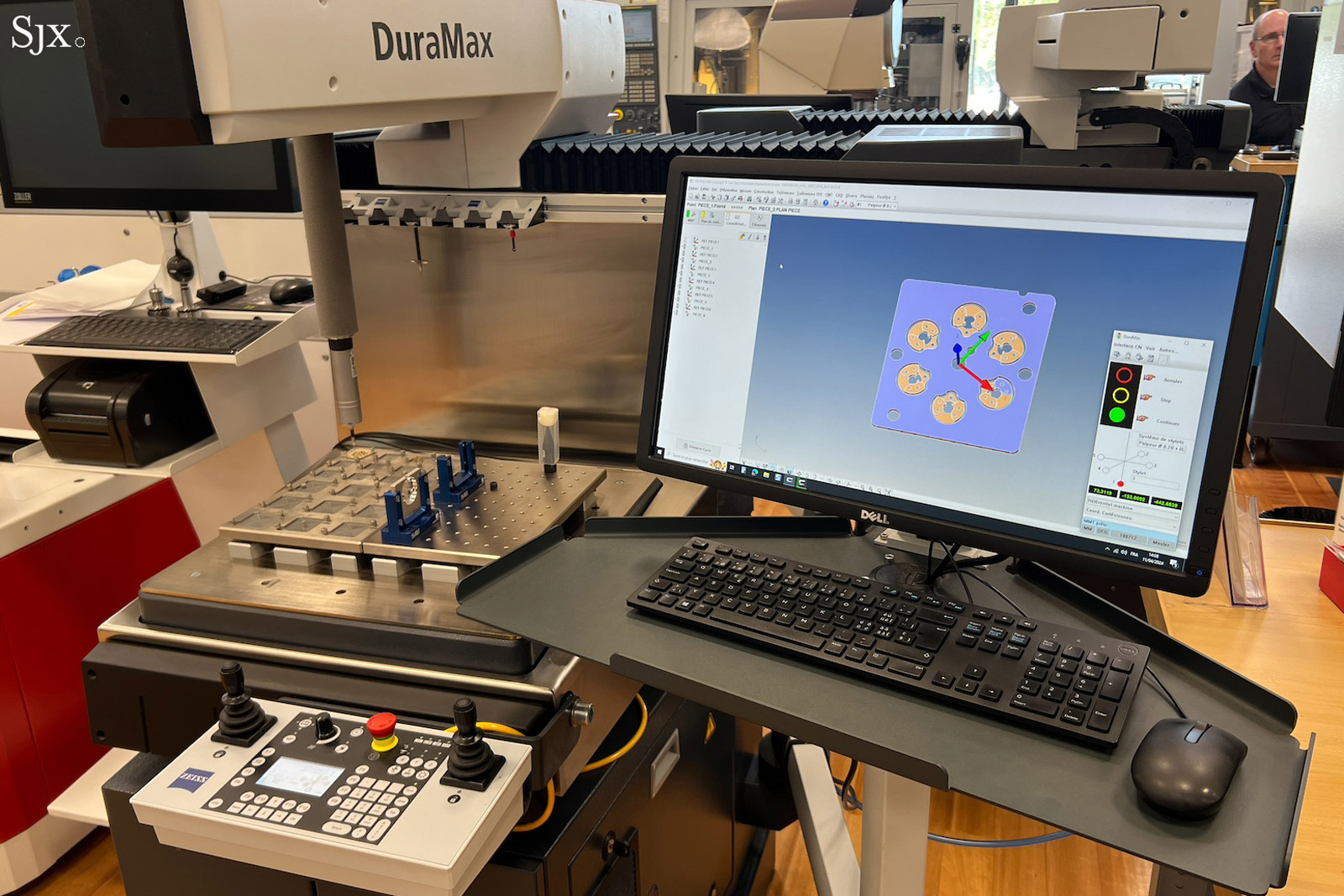

Quality control happens in real-time throughout the production process. This involves both mechanical and optical sensors to ensure that each component conforms to its specifications.

Escapement production

In many ways, watch factories tend to be pretty similar from one to the next, and only a few brands can claim to make their own escapement components and hairsprings in-house. Among them is VC, which produces its own assortments (the industry term for the kit containing the escape wheel, lever and balance wheel) and hairsprings under the same roof where decoration and final assembly occur.

This is unusual because these components, among all the components in a watch, are the most sensitive to variations in quality. The production of these components also requires specific skills, know-how, and specialised equipment. For this reason, most brands still rely on a few key industry suppliers, like Swatch Group-owned Nivarox, for assortments and hairsprings.

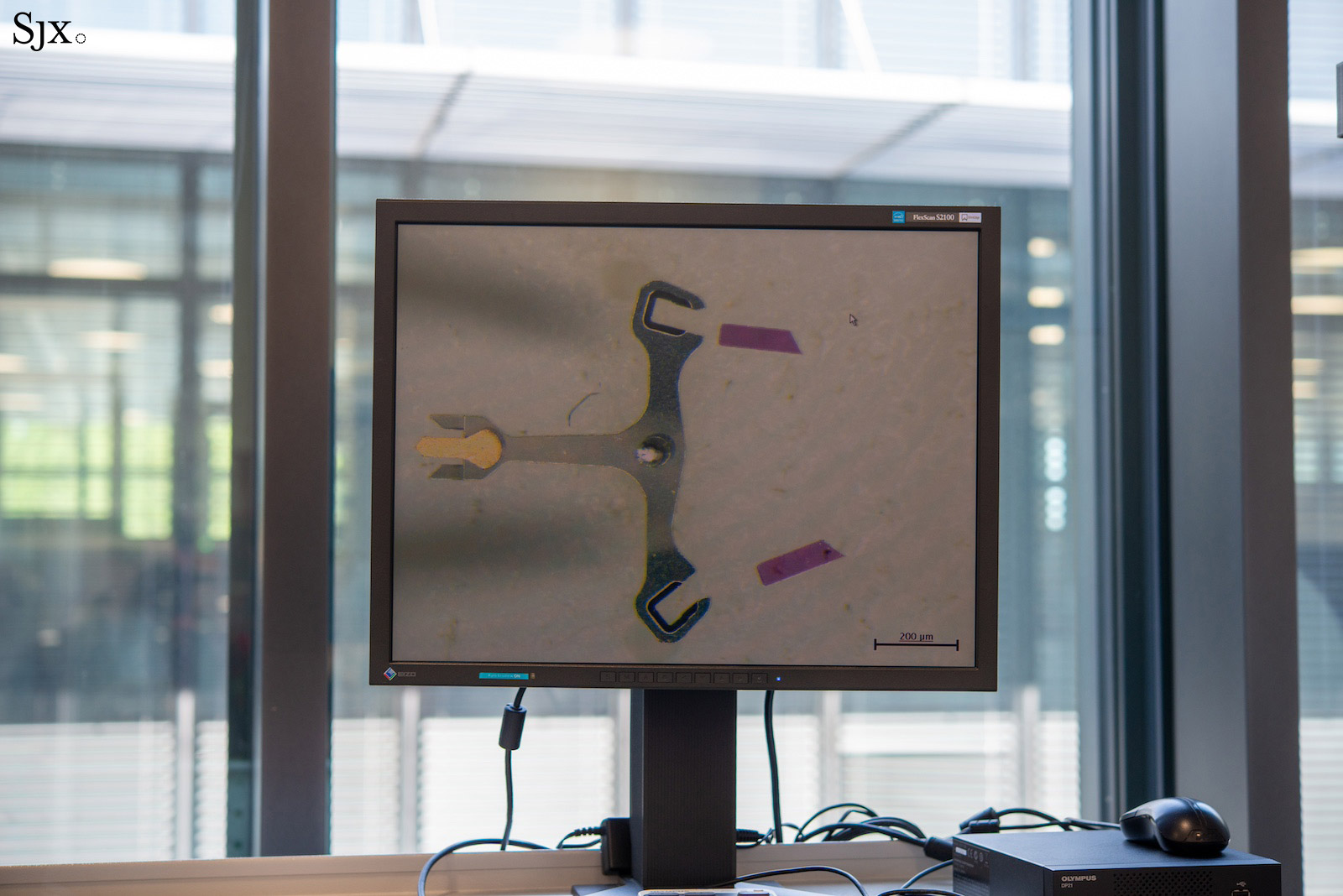

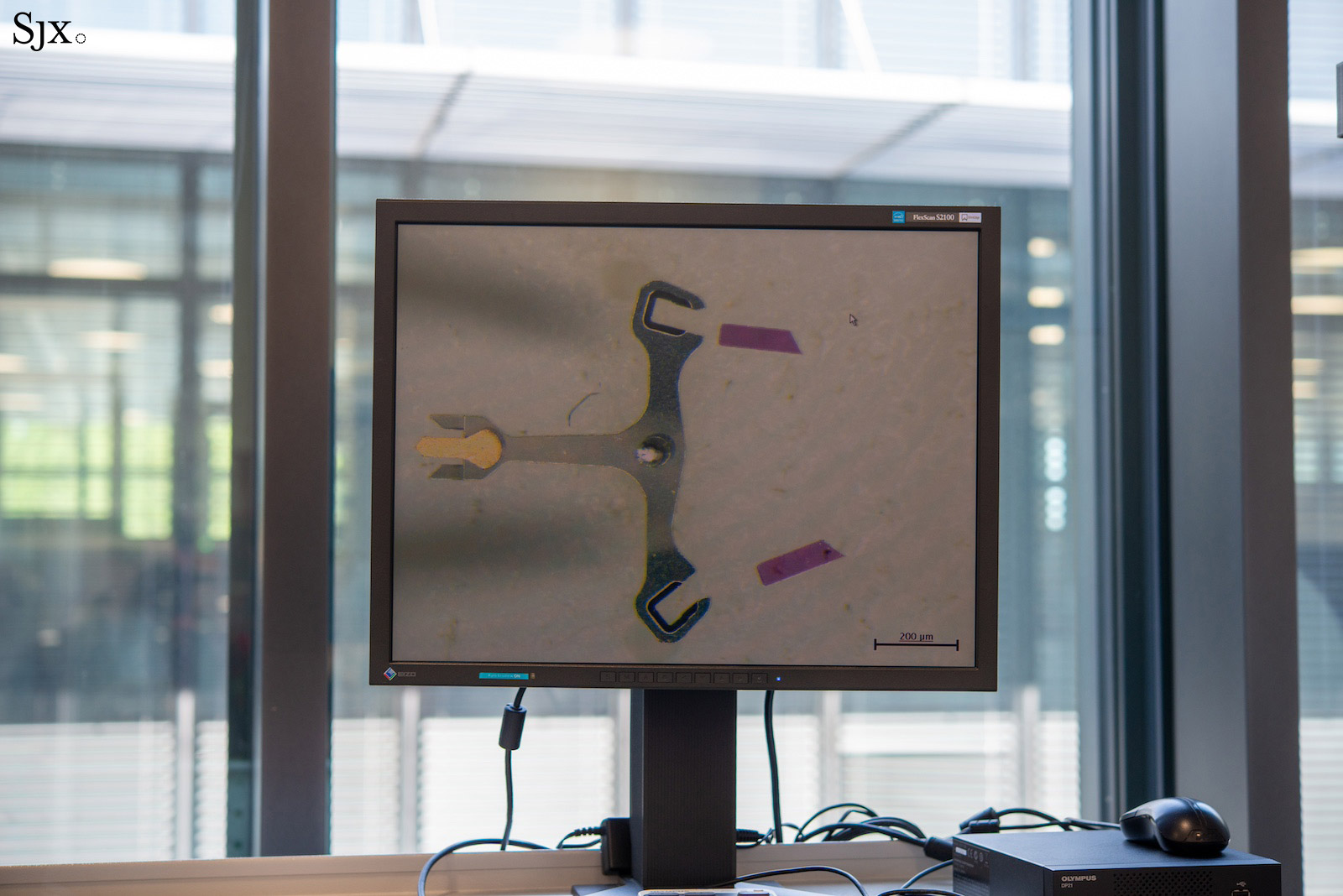

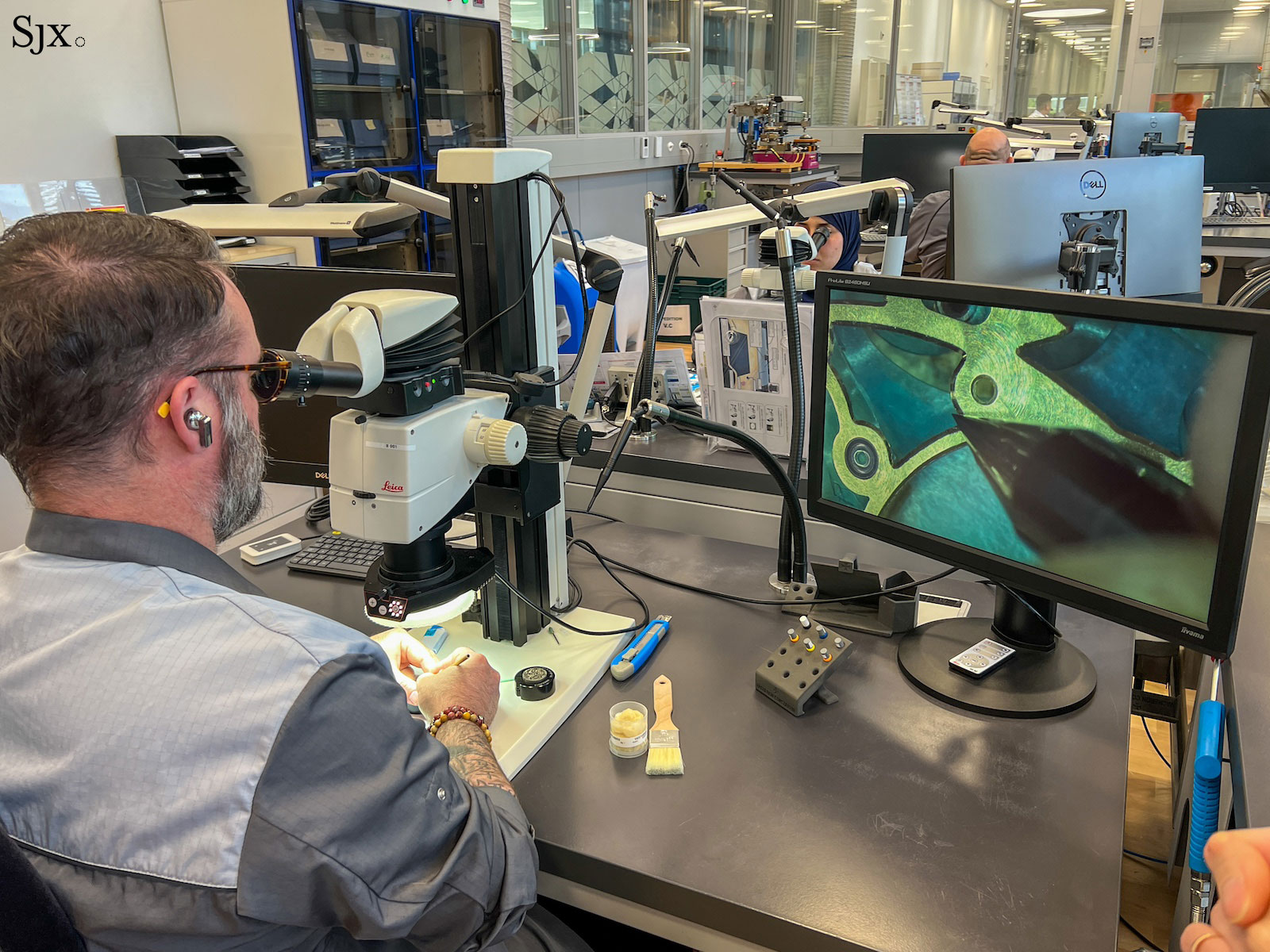

In this context, it was a rare treat to see how these components are produced. For example, for each escape lever, each pallet stone is set manually, one by one. Using special jigs and working with the help of a microscope, the watchmakers are able to produce jeweled levers quite quickly thanks to their skilled touch and the perfect setup of their equipment.

The production of hairsprings was another key stop on the tour. Special equipment is used to draw the wire through gauges of decreasing diameter, before being rolled flat. At this stage, before heat treatment, the wire is as formless as human hair, and does not yet have the elasticity of a functional hairspring.

The elasticity is literally ‘baked in’ using a special oven. A set of four hairsprings are made at a time, coiled into a special jig.

If you’re wondering why four springs are made at a time, it’s because the distance between the coils is equivalent to the thickness of three coils. After heat treatment, the springs are now elastic and can ‘breathe’ in and out during oscillation.

The cylinder at right is the oven used to ‘bake in’ the elasticity of the hairspring.

After heat treatment, hairsprings are formed into shape across the hall. This includes manually forming overcoils for the brand’s higher-end products. At a time when brands are increasingly turning to fuss-free silicon for hairsprings, VC’s ongoing commitment to traditional metallic hairsprings is reassuring.

Forming hairspring terminal curves.

Finishing

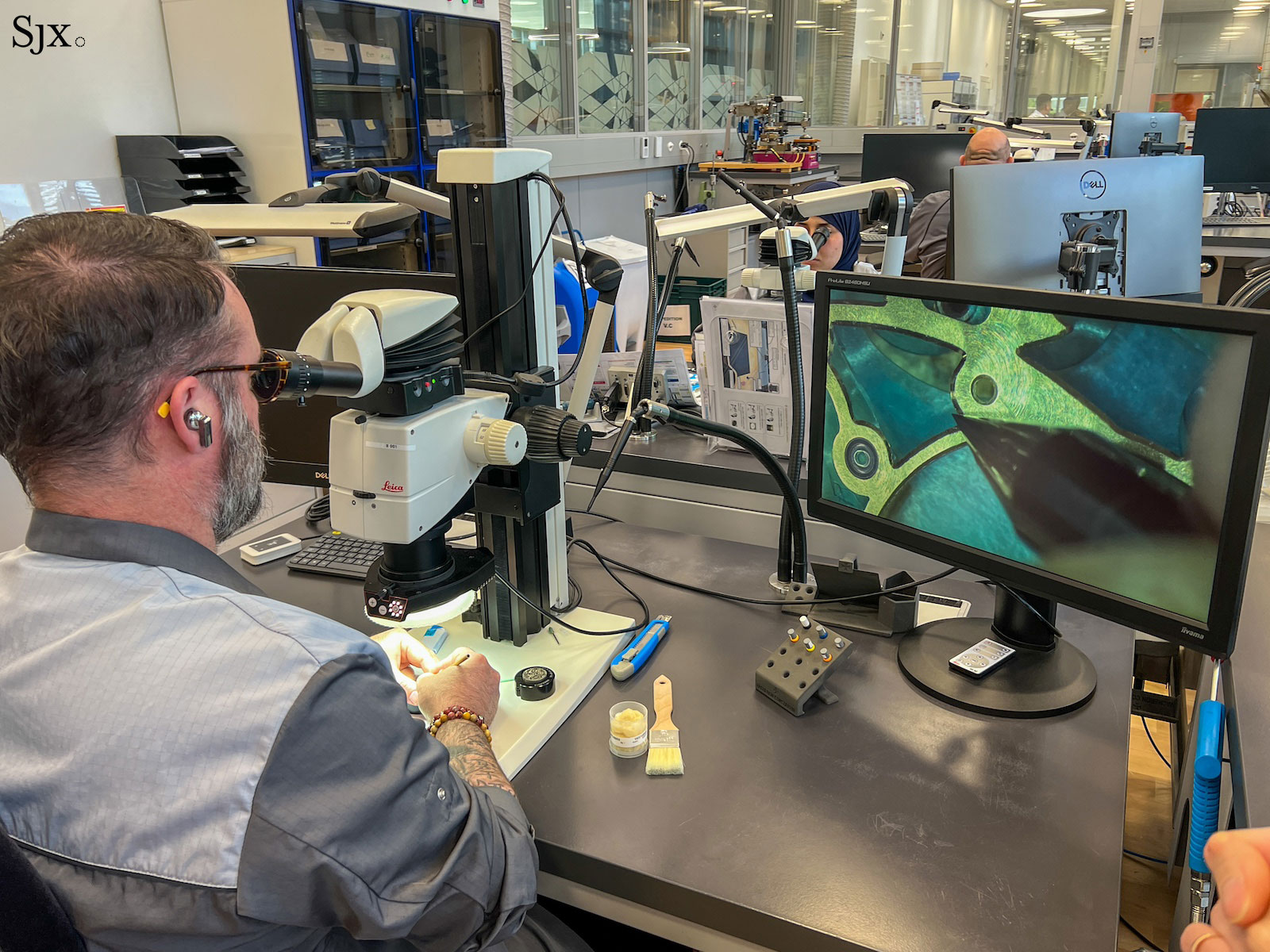

Naturally for a brand that submits many of its products for the Geneva Seal, finishing is a major focus for VC. Finishing work is organized by component type, with special tools provided for each type of work.

For example, the steel wheels in the winding train are polished with abrasive paper that is constantly changed using a special machine, ensuring that all parts receive the same treatment. But even this machine requires the sensitive touch of an expert, since the pressure is applied manually, and leaving the component in contact with the abrasive surface for a moment too long can ruin the part.

Even the unseen parts of the movement, such as the ends of the balance staff, are finished carefully using purpose-built equipment. This vital step helps ensure completely uniform finishing of these delicate surfaces, reducing friction during oscillation of the balance.

Balance staff pivots are polished using purpose-built equipment.

Anglage is another key aspect of finishing at VC. In the image below, a watchmaker is using a sharp metal file to apply anglage to an openworked movement bridge. The watchmaker’s quick, confident strokes produced results quickly, with the soft brass of the movement bridge easily giving way to the hardened edge of the file.

It’s worth exploring the fact that this method of finishing does not remove metal from the bridge. In fact, after completing this entire bridge there were no metal shavings on the work surface. Instead, anglage is essentially the process of work-hardening the material by smoothing it out.

Assembly

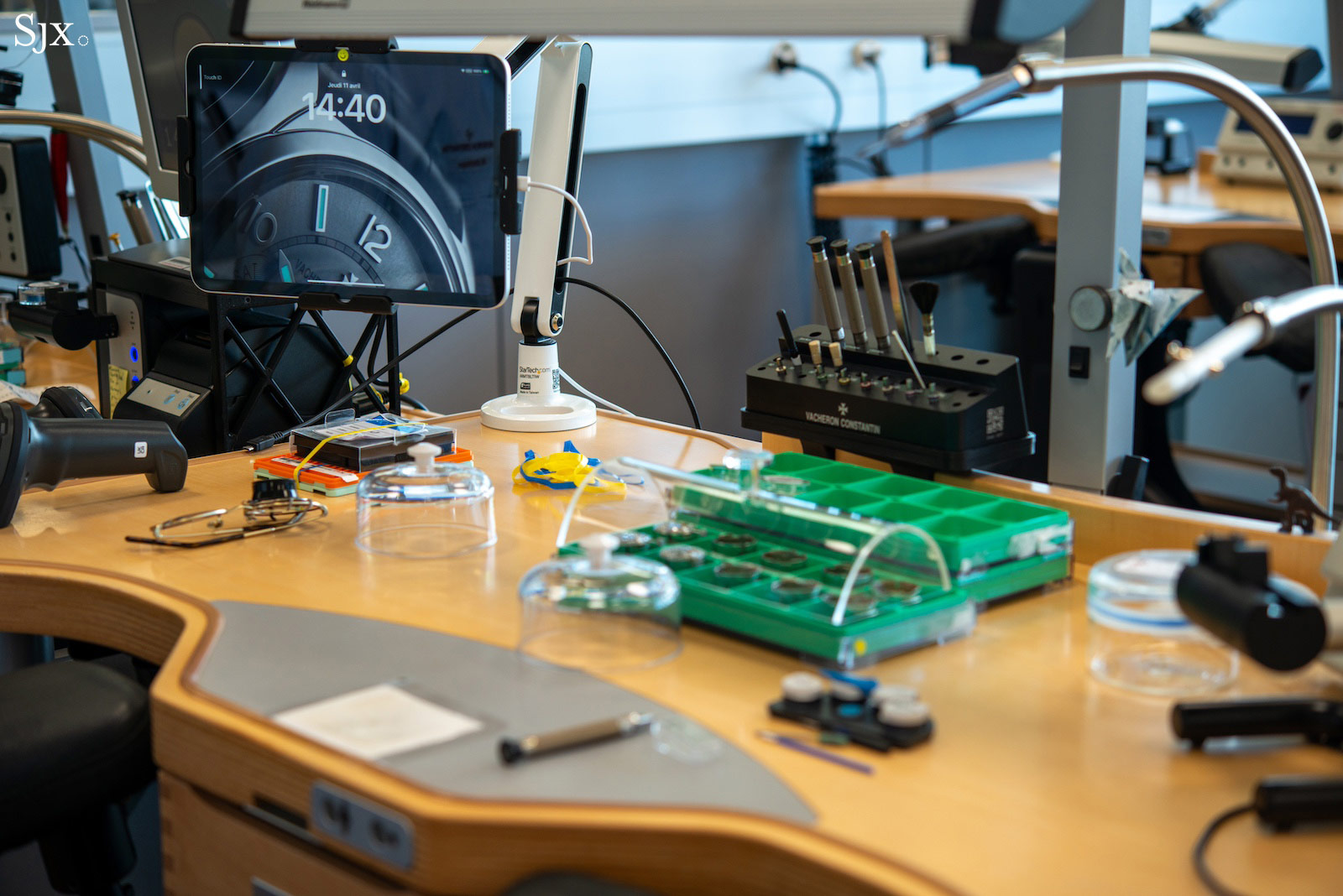

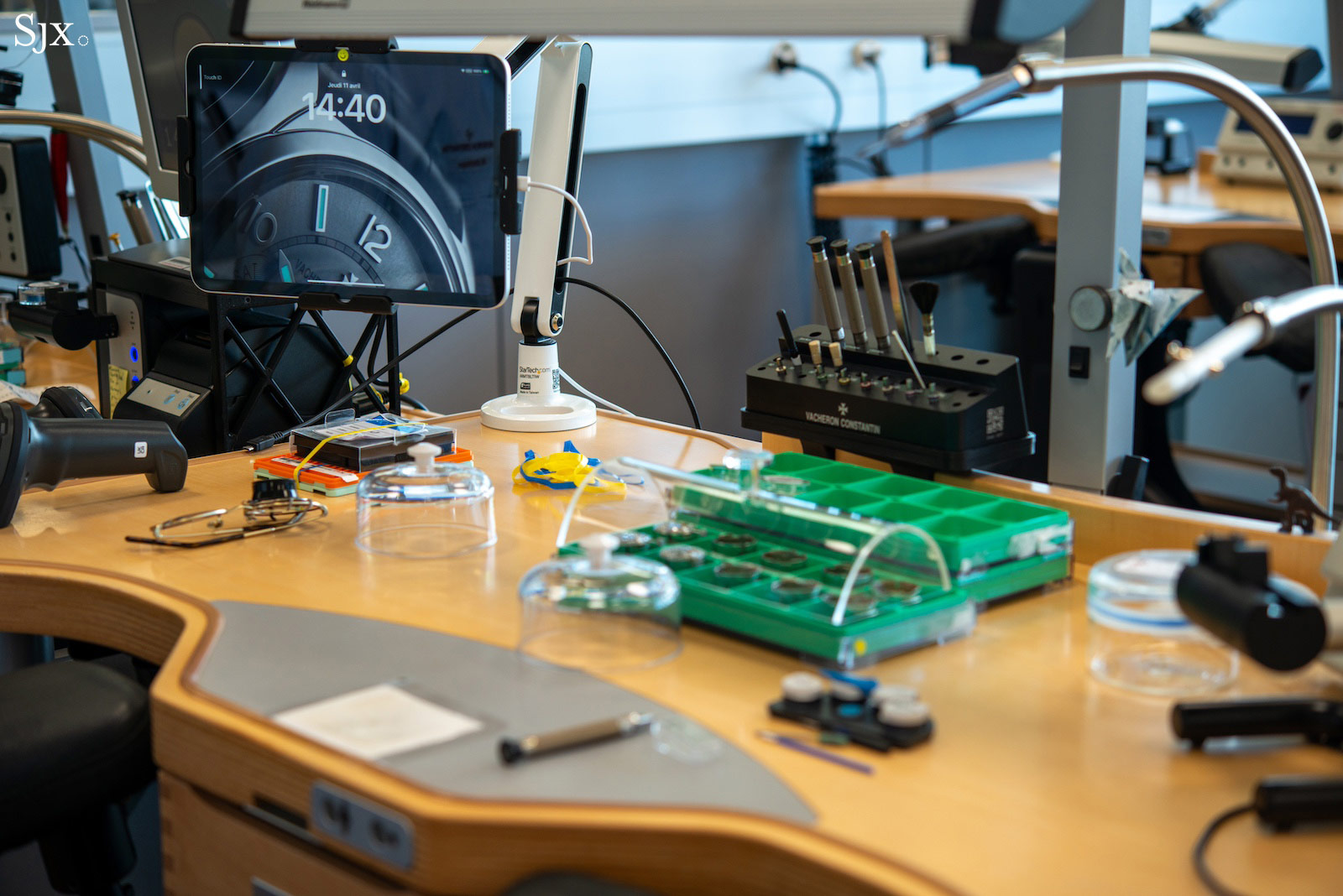

The assembly of each Vacheron Constantin watch takes place in a series of spacious and well-appointed workshops. Workshops are segmented by the level of complication, with tourbillons, minute repeaters, and other complications assembled by dedicated teams of watchmakers.

The watchmakers’ benches are equipped like those of any haute horlogerie manufacture or high-end independent brand. But there are also a few distinguishing characteristics reflecting high-tech equipment, like the fact that VC has transitioned to using only torque-limiting screwdrivers for assembly, ensuring that every screw is tightened to the optimal level without putting undue stress on the screw heads.

Artisanal crafts

Vacheron Constantin has established a reputation as a leader in métiers d’art, a broad terms that encompasses various artistic forms of decoration. These techniques, which include guillochage, enamelling, engraving, and gem-setting, are practiced in a dedicated workshop staffed by a small team of skilled artisans at the top of their respective fields.

This department is responsible for the brand’s Les Cabinotiers bespoke watchmaking services, as well as the production of artistic dials for certain limited editions.

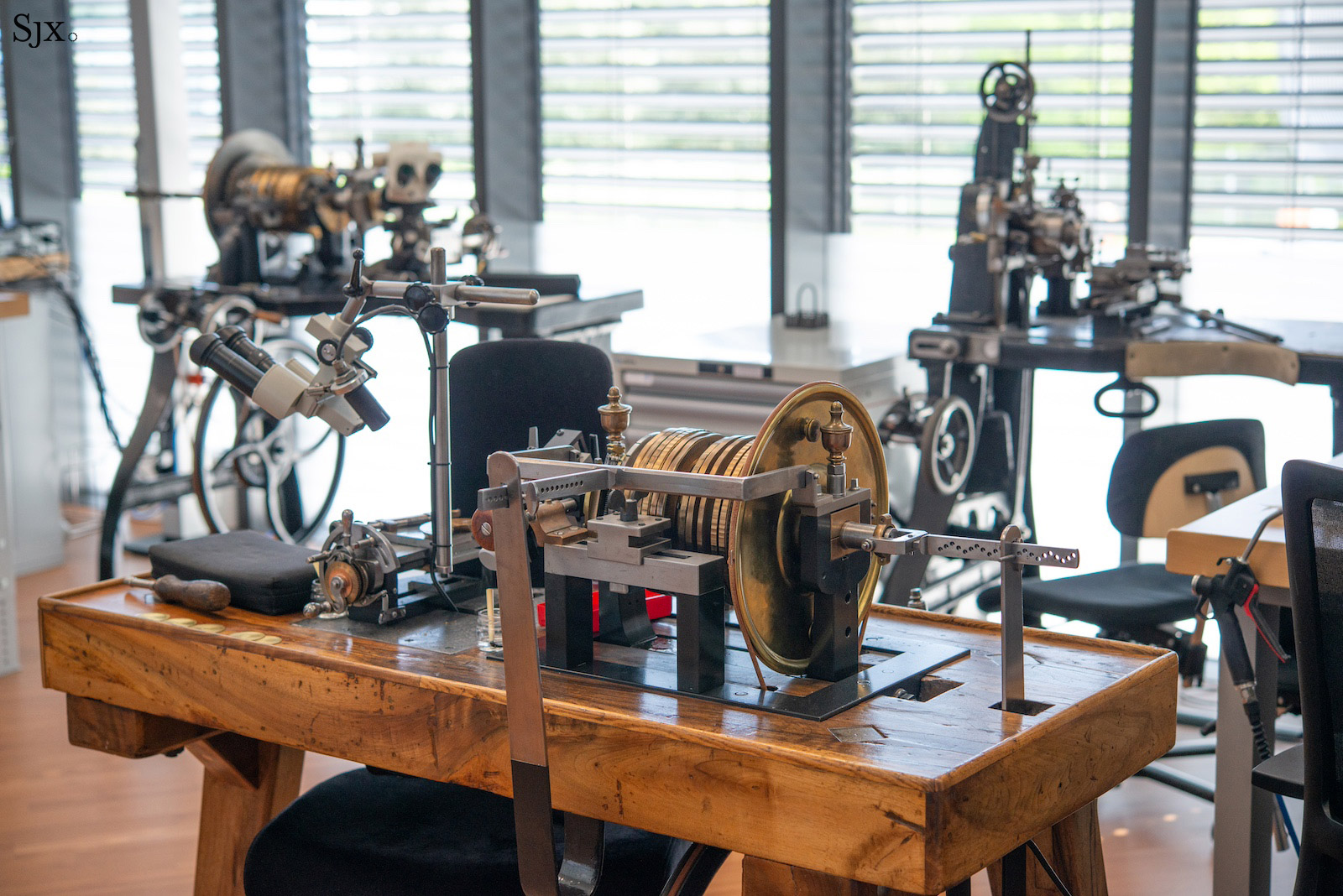

When one thinks of guilloche, the names that come to mind tend to be brands like Breguet and independents like Roger Smith, Kari Voutilainen, and J.N. Shapiro. But VC has a long history with guillochage, and today operates a workshop equipped with several straight line and rose engines.

The author revisiting his training.

Even though it might not be the first brand that comes to mind when it comes to guillochage, VC is arguably a leader in the craft when it comes to design. The brand has developed some highly creative patterns, some evoking M.C Escher, using traditional guilloche, including scenes inspired by nature, like a school of fish, and others inspired by architecture, such as the Chrysler building in New York.

The scales on each fish are engraved using guilloche techniques.

A rendering of the Chrysler Building in New York, made using guilloche machines

Vacheron Constantin also has unique in-house talent when it comes to enamelling, especially grisaille enamel. With this technique, which translates as “in the grey,” a relief pattern is achieved by varying the thickness of a top layer of white enamel over a dark base layer, usually black but occasionally other colours.

This subtle, monochromatic enamelwork is highly distinctive, and the brand’s in-house enamel artist Laurent Ramat has produced some outstanding creations.

One of his secrets is his use of a special brush tipped with a single cactus thorn, which he uses to create his patterns in the top layer of enamel with the aid of a microscope. Even the cactus is in-house, sitting on a shelf behind his bench, meaning he has ready access to fresh thorns.

An example of grisaille enamel. Image – Vacheron Constantin

Engraving and gem-setting are also key skills practiced in this department. During the tour I was fortunate to witness the creation of a bracelet for the Grand Lady Kalla, a magnificent piece of high jewellery featuring more than 45 carats of diamonds.

The gem-setting and engraving benches are next to one another, which has proven vital for some of the highly complex designs this department has created in the past.

For example, the engraver recalled a special commission with a highly complex design that required engraving before and after each gem was set into the case. This means the case was repeatedly handed back and forth between the two artisans throughout the production process.

An example of engraving and gem-setting on a one-of-a-kind Les Cabinotiers creation with emeralds discreetly set on the repeater slide

If VC did not have these skills in-house, the result would have been a time-consuming and tedious process of shipping the case back-and-forth between various suppliers for each step of the process. But having this expertise in-house, at adjacent workstations, enabled the artisans to work closely together and share feedback in real-time, resulting in a higher quality product.

Restoration

As the oldest continuously operated watch company in the world, Vacheron Constantin has a unique responsibility, and capability, when it comes to restoration.

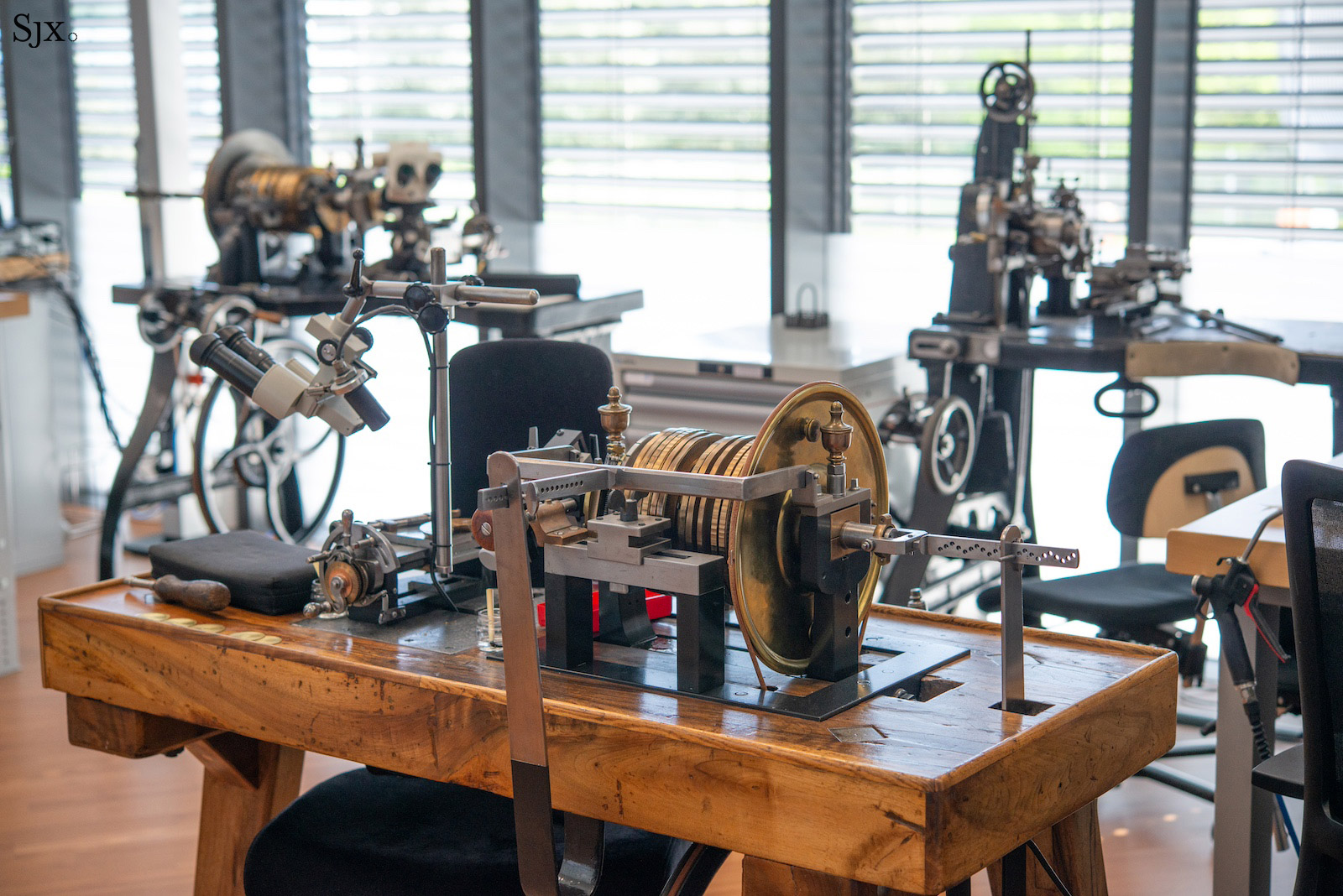

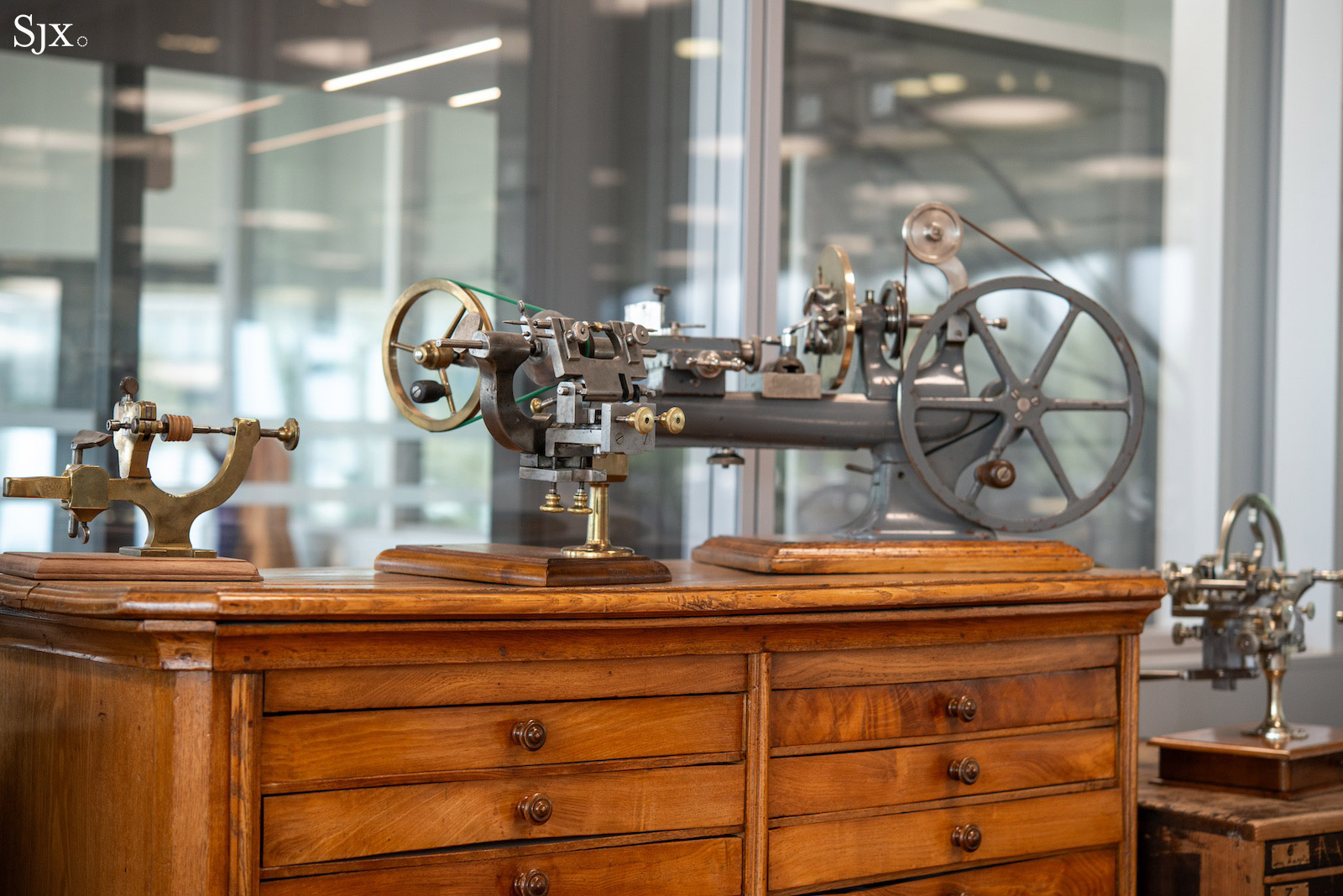

Thanks in part to its uninterrupted history, the brand has maintained a vast stockpile of historical components, including crystals and dials. If the brand is restoring something and does not have the required part in stock, watchmakers use period-correct equipment to fashion truly authentic replacement parts.

These types of vintage lathes and other tools are often used to decorate brand boutiques and manufactures, but in this department they are regularly used, as evident by their state of cleanliness and the presence of reference marks used by watchmakers.

Closing thoughts

The Vacheron Constantin manufacture is a significant part of the watchmaking landscape in Geneva. While industrial in scale, capable of producing more than 20,000 movements per year, the manufacture is nonetheless also capable of some of the most extraordinary artistic craft in the industry.

This blend of science and art turned out to be a recurring theme of my visit, something that I noticed in various areas. While watchmaking can be an art form, equally impressive are those that have turned watchmaking into a science, using clever engineering to routinise artisanship. Vacheron Constantin is a leader among them, with a long tradition of production innovation that dates back to the 1840s, to go along with its history of fine craftsmanship that dates to its founding in 1755.

Back to top.