Sotheby’s upcoming auction in New York brings to light a pair of remarkable Patek Philippe pocket watches with double movements once owned by John Motley Morehead III (1870-1965), an American patron of the brand with exotic taste.

Unknown even to Patek Philippe until now, the two watches each include a primary minute repeating base movement with a secondary movement under charismatic doré dials. Beyond their intrinsic rarity, the golden duo are significant from a historical perspective in offering a portal into early 20th-century American watch collecting, when interest began to shift from decorative to technical.

The who

A chemist who helped form Union Carbide, Morehead seems to have had a penchant for unusual, highly complicated watches.

He also owned a triple complication with upside down “American” perpetual calendar, carillon minute repeater, and a double chronograph (as in, two separate chronographs) as well as a rattrapante but with only two seconds hands. The excellent research by Sotheby’s uncovered record of another of Morehead’s watches that was a carillon repeater with two sets of hands, like these watches, but powered by only one movement.

Both double-movement watches going on the block at Sotheby’s have a primary movement with minute repeating on the back and a secondary simple movement on the front. The smaller of the two makes do with just a minute repeating base movement, while the larger watch also has a split-seconds chronograph with a minutes counter.

The duo sport yellow gold dials to match the case, rather than enamel that was typical for the period. Both movements can be wound from a single crown, and set with the combination of a pull-out crown and pin.

No. 197’589 – Double movement with minute repeater

Patek Philippe built the first watch, no. 197’589, in 1920 and sold it to Morehead two years later. Like all of Morehead’s known watches, the dust cover is engraved “Made for John M. Morehead by Patek Philippe & Co”. The hands are coded by colour and form: blue spade hands for the primary movement and gold Breguet hands for the secondary.

Watch No. 197’589

The United States was Patek Philippe’s most important market of the time, and this watch exemplifies American taste. The slim bassine case – 12 mm without crystal thanks to the flat movements – and concealed hinges give the case a sleek, modern look. Most of Patek Philippe’s hidden hinge watches, which won’t snag when pocketing a watch, were made for the American market.

Movement of watch No. 197’589

The dial also reflects American tastes at the time. The combination of thick block Roman numerals and Breguet hands appears on many watches sold by important American retailers such as Tiffany & Co. or Shreve, Crump & Low.

A tangible illustration of diverging transatlantic tastes lies in watch no. 174’129 that was made for James Ward Packard. The watch was first exhibited in Europe with a different dial before delivery to the American industrialist, clearly showing the difference in American and European taste.

Images – Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie 1914 (left), Patek Philippe (right).

No. 197’590 – Double movement with minute repeater and split-seconds chronograph

Patek Philippe completed Morehead’s second watch, which has a sequential movement number, in 1924, and he took delivery the following year.

It is significantly larger at 55 mm in diameter – about 10 mm larger than the previous – and about 20 mm thick without the crystal. Two factors contribute to the height. First, both movements look to be about normal height, unlike the extra-flat movements paired in the previous watch.

Watch No. 197’590. The switch between the pendant and split seconds button locks the chronograph buttons, a common feature on Genevan watches.

Second is the addition of a split-seconds chronograph to the primary movement. Not only does this increase the height of the movement on the back, it also adds two additional hands to the front.

The towering hand stack includes two hands for the hours, two for the minutes, and two for the split seconds chronograph. With six hands in total, it ties the Calibre 89 for tallest (currently known) Patek Philippe hand stack.

Art Deco-esque bold arabics such as these were often filled with radium, which is hazardous to human health and damaging to dials. Thankfully, this doré dial was spared from illumination.

The Patek Philippe signature is not period correct, which is unsurprising; while enamel dials may still look new after a hundred years, metal dials need some help. Though the dial is the most important part of a watch to many wristwatch collectors, with complicated pocket watches the movement arguably matters most.

Movement of watch No. 197’589. The movement decoration is, of course, excellent.

Patek Philippe would have sourced both movements from Victorin Piguet, an etablisseur in the Vallée de Joux that specialised in complicated or unusual movements that had a close relationship with Genevan manufacturers.

The why

While we know for whom these watches were made and how they operate, the answer to the question of why they exist is more elusive.

In 1930, not long after Morehead took delivery of his double-movement watches, several American newspapers printed the humourous page-filling quip “Retail jewelers assert that every man should carry two watches. But a man with one watch knows what time it is, and a man with two watches could never be sure”.

The implication being that jewellers wanted to sell more watches, yet there might be some merit to the idea. Morehead does mention carrying two watches in letters unearthed by Sotheby’s research, and wasn’t the only American collector to do so.

Today, it is easy to tell if a watch is off as you can always consult your phone. In the past, however, spotting issues wasn’t as easy – unless you carried two watches. If both watches are keeping good time, they will be in agreement. If one is keeping good time, and the other is not, you may not know the correct time, but you know something is amiss, which you’d be ignorant of with only a single watch.

To take this even further, if you carried three watches – or two watches, one of which with two movements – you could reasonably assume the correct time if two agreed and one did not. According to Dava Sobel’s A Brief History of Early Navigation, “It was not uncommon for one ship to rely on two or even three chronometers, so that the timekeepers could keep tabs on each other.”, and survey ships could carry many more to establish consensus.

Sidereal time

One of the most compelling explanations is that one movement tracks mean solar time, and the other, sidereal time. A sidereal day is one full rotation of the earth, which takes about 23 hours 56 minutes 4.091 seconds. It is essentially your local right ascension, which is the celestial equivalent of longitude, with its own celestial equator. Unlike terrestrial longitude, right ascension is normally expressed in time rather than degrees, with 24 hours being equivalent to 360°.

Sidereal time tells you what the sky looks light over head. For example, if you watch reads quarter-to-seven in sidereal time it means Sirius (the brightest star in the sky) is directly overhead. This explanation works especially well as Morehead had such a passion for the stars that he donated the Morehead Planetarium to his alma mater, the University of North Carolina. The only issue is that sidereal time is expressed on a 24-hour time scale, though 12-hour chronometers that were used as ad hoc sidereal timekeepers do exist.

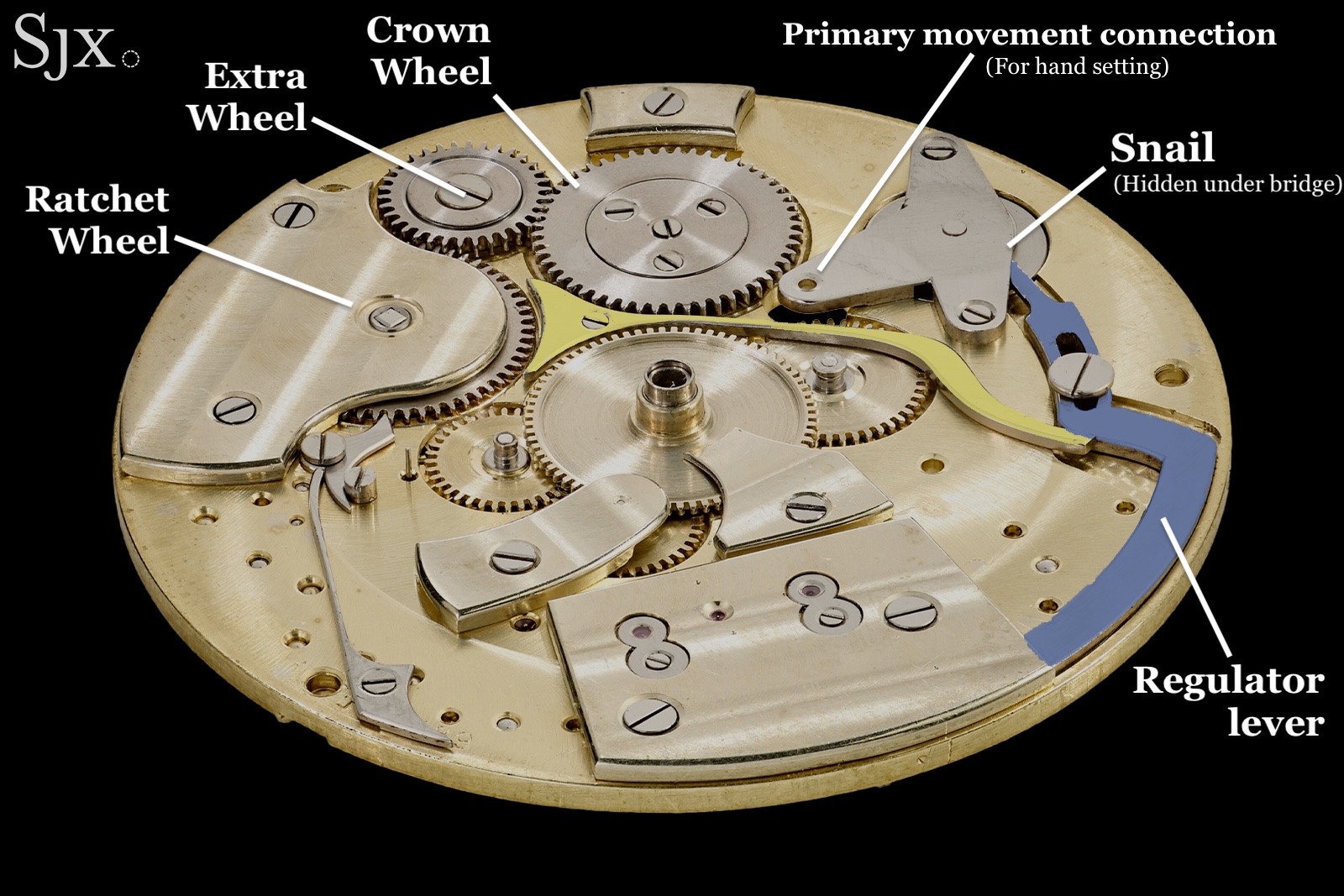

It was possible to track sidereal time using a single balance and gear ratios as demonstrated by another watch in this auction – the S. Smith & Son Astronomical Watch made by Audemars Piguet, which depicts the sky over Trafalgar Square, where the firm was headquartered at the time. However, such a solution adds inherent additional inaccuracy. Patek Philippe calculated 25 trillion different trains to achieve the Sky Moon Tourbillon’s error of only -0.088 sidereal seconds per day – impossible without computers.

That said, the train used by Leon Aubert for the Leroy 01’s planisphere achieved an error of only -0.157 seconds with a 365:366 ratio. Though watches using a two balance solution exist even today, such as the Arnold & Son DBS. Since the watch has seen multiple services, it is not possible to determine if one movement was adjusted to sidereal time from the factory.

The S. Smith & Son Astronomical Watch, also known as the “Grosse Piece”

Dual time

Surely no one would make a movement with two separate balances just to indicate two different time zones – yet such watches exist. The Erivan Haub collection, also sold by Sotheby’s, included an excellent example (though in rough condition) made for the Turkish market with cadran europée (European dial) and cadran (Turkish dial) to keep track of Turkish and Central European Time – which much of continental Europe had adopted by 1910, when the watch was made.

Image – Sotheby’s

The how

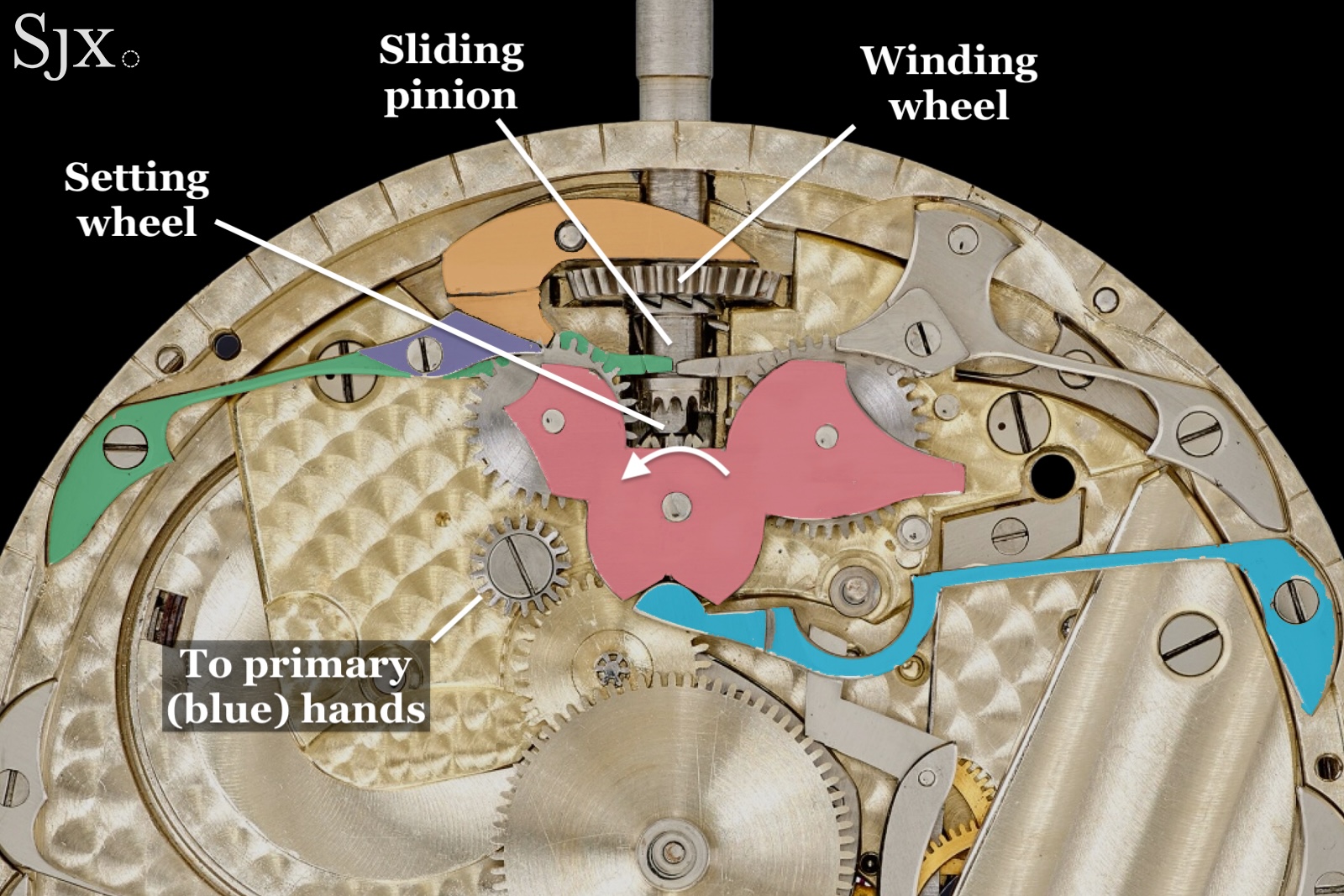

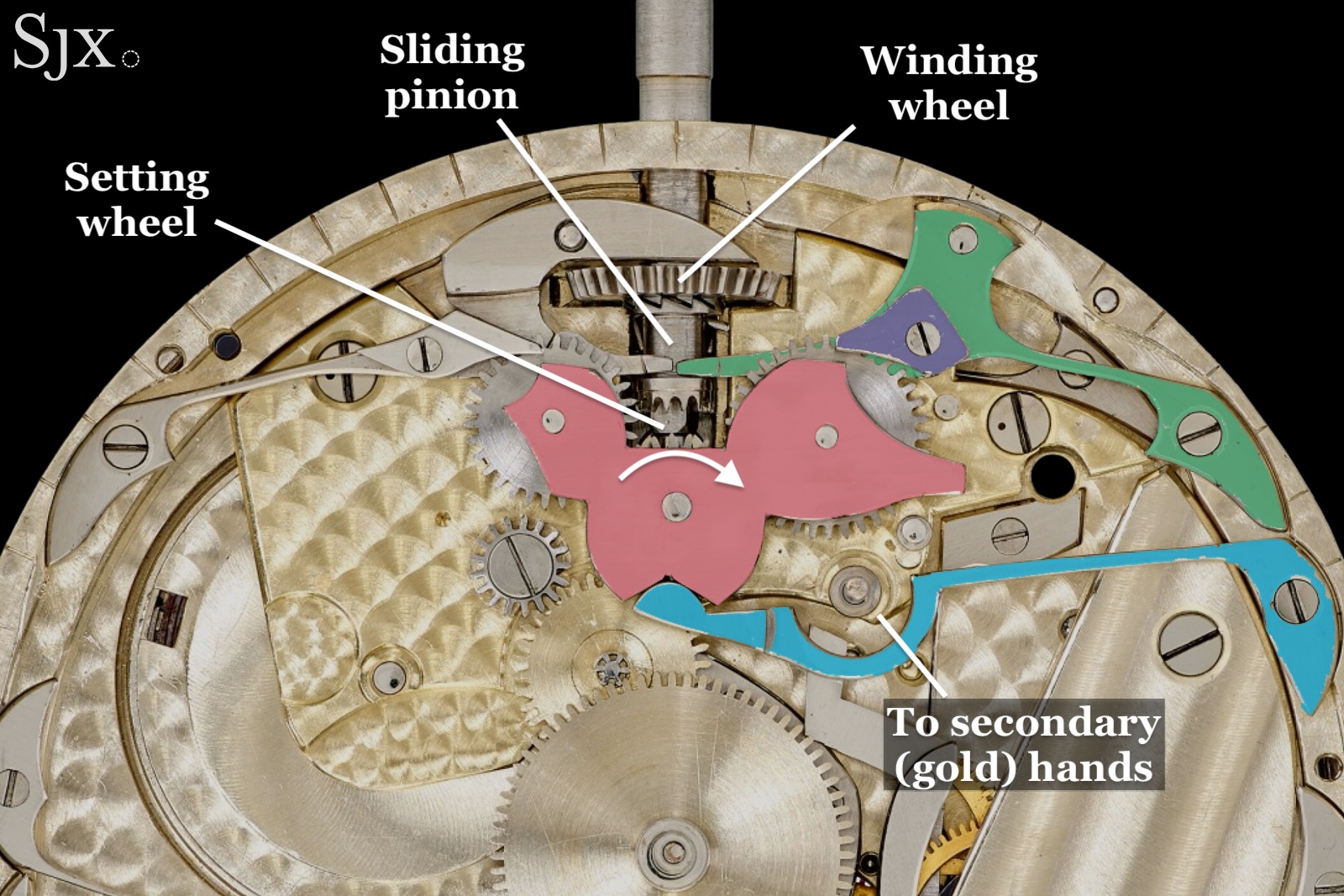

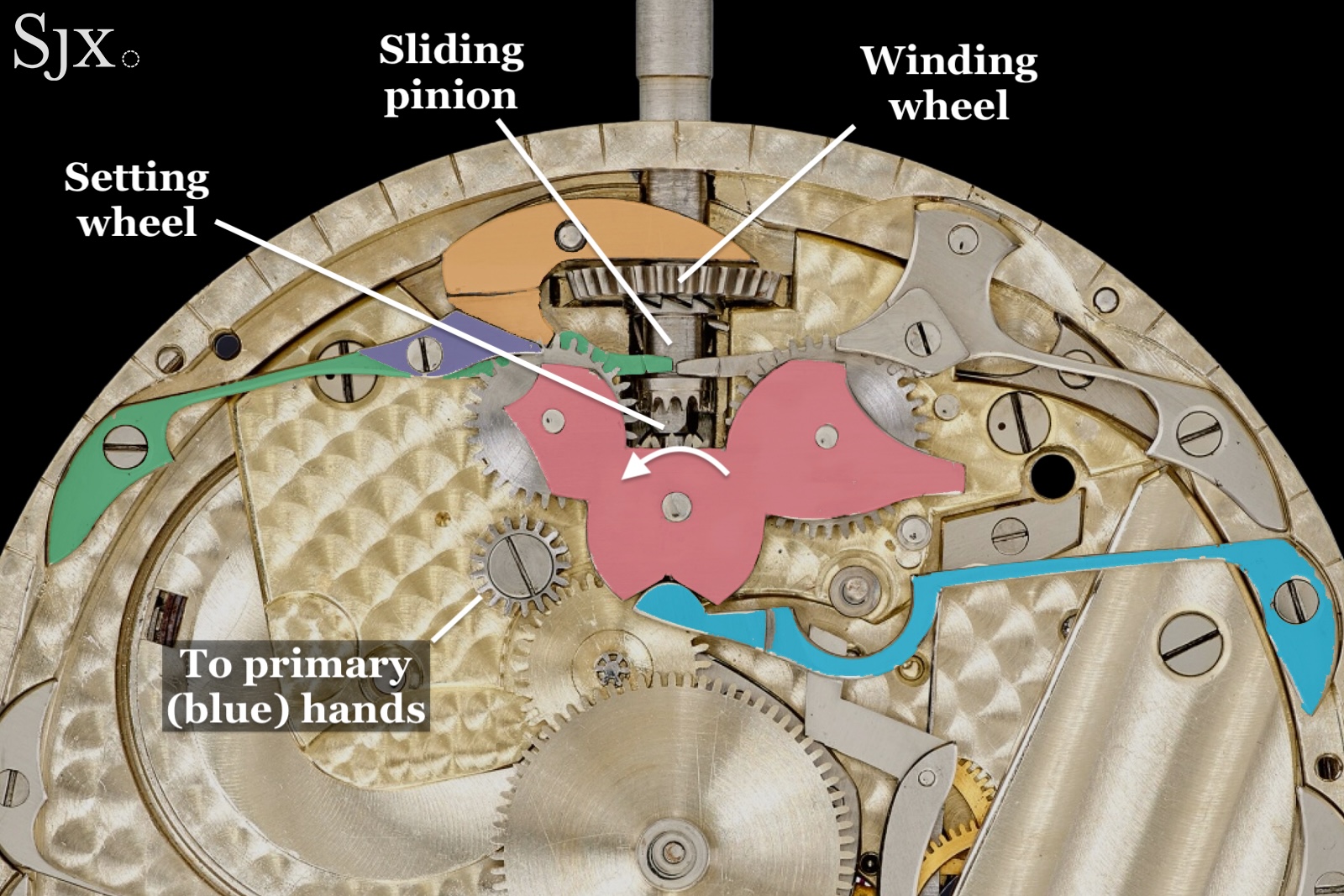

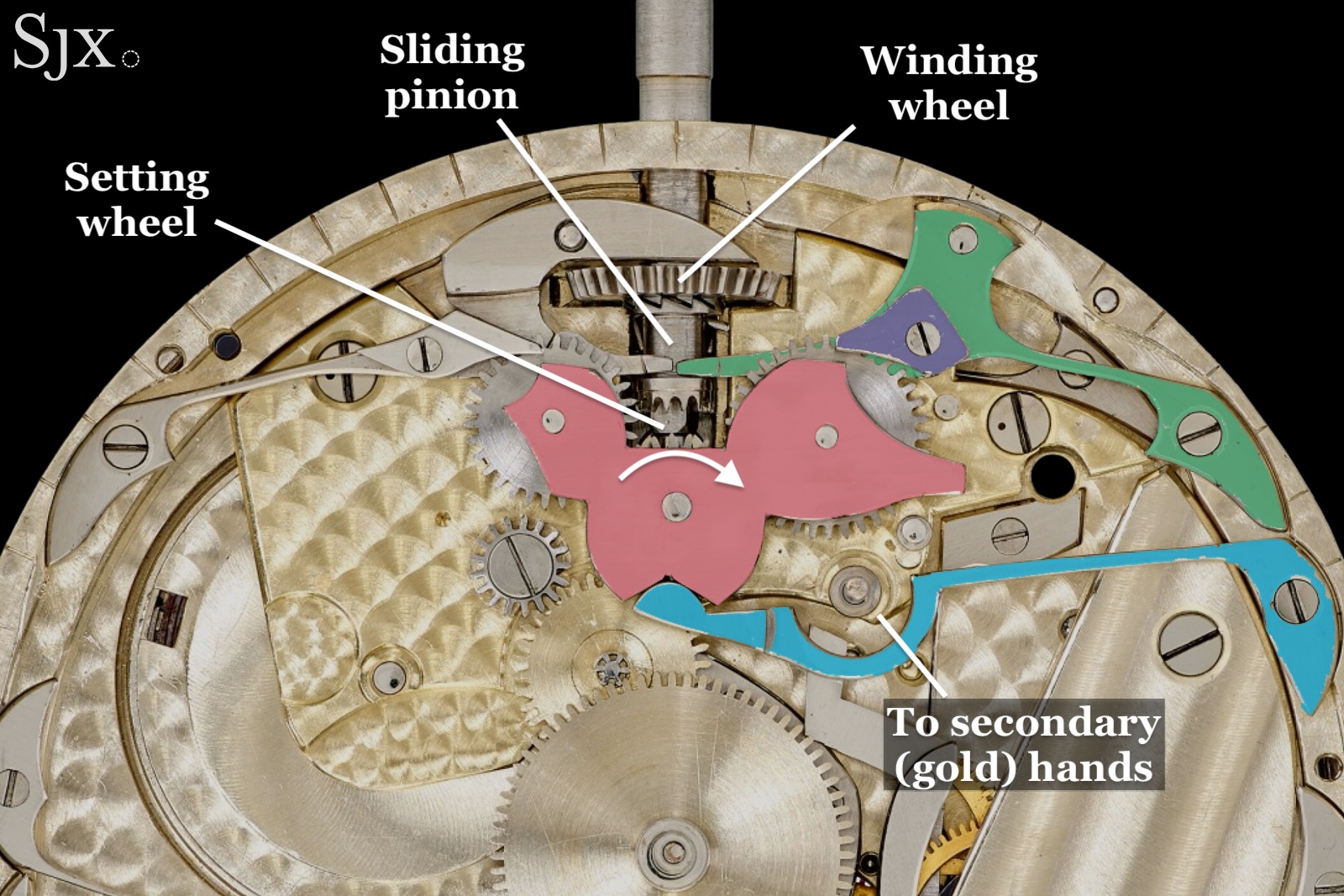

Both double-movement watches use Adrien Philippe’s sliding pinion system, which Patek Philippe still uses today – as does nearly every other manufacturer.

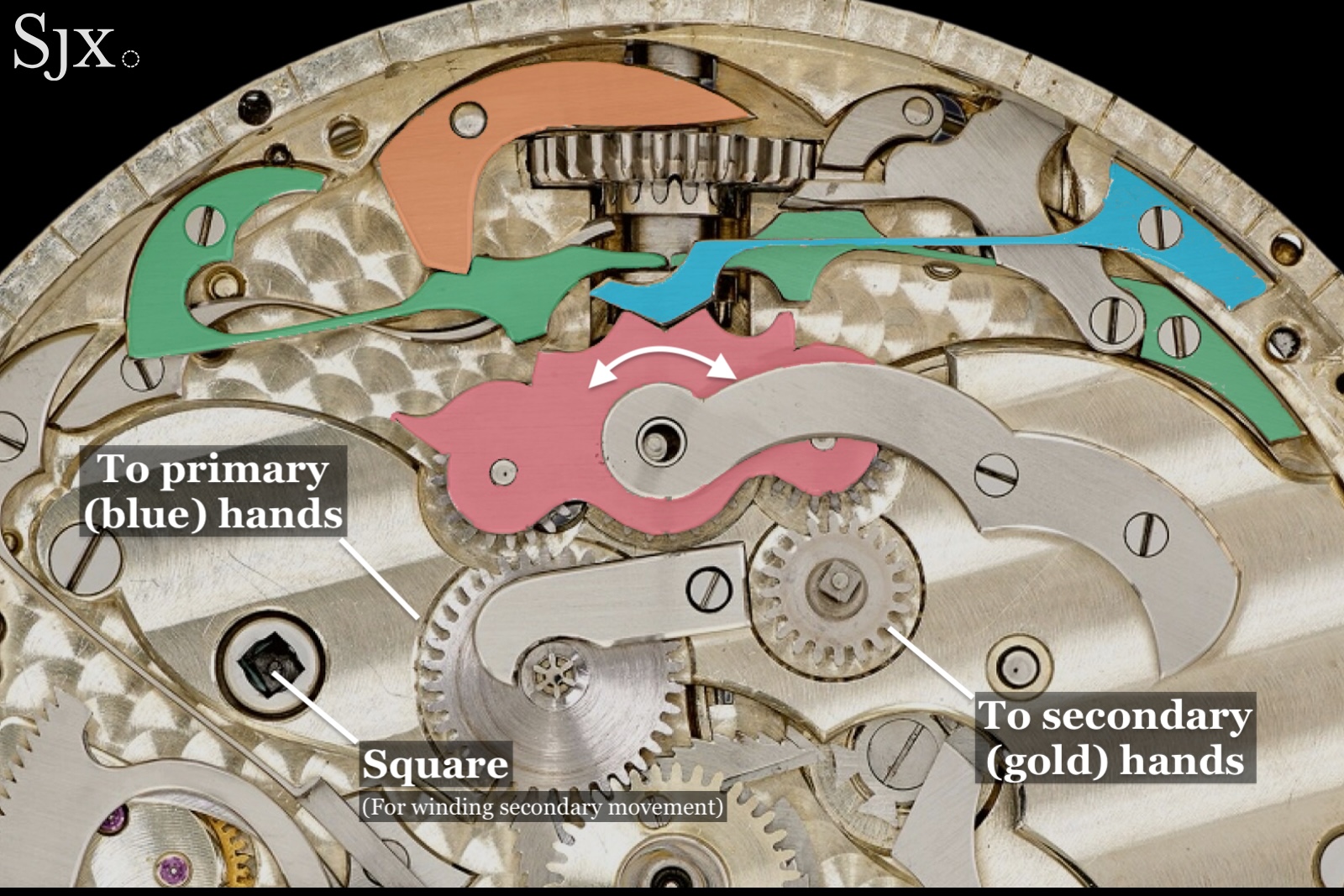

Pulling the crown out causes the setting lever (orange) to pivot, causing the yoke (green) to push the sliding pinion forward, disengaging from the winding pinion and engaging with the setting pinion.

The setting pinion connects to a (red) rocker, a (blue) spring keeps this rocker centred normally, but when the crown is pulled a (purple) piece attached to the (green) yoke pivots the rocker, connecting the crown to the primary movement’s hands.

You will notice that this is mirrored on the other side. Pressing the pin in the case band at two o’clock moves the second yoke (green) pushing the sliding pinion forward to meet the setting wheel. A (purple) piece on the yoke pivots the rocker in the other direction, mesching with a wheel (not shown in this image) with a shaft that connects to the secondary movement.

The same principles apply to the larger watch, as seen below.

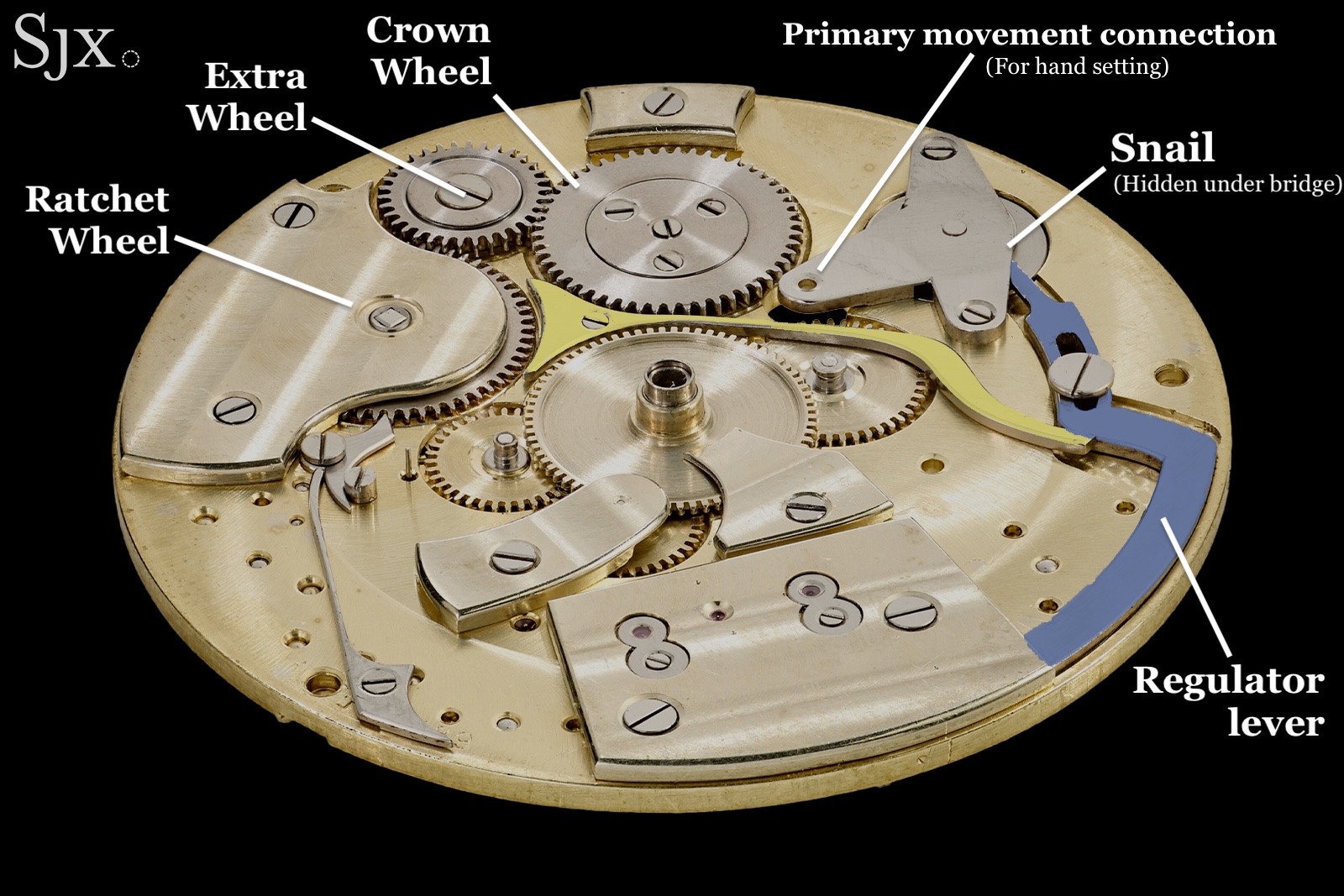

Winding is where the two differ the most. On the smaller of the two, both movements share the same winding pinion, a cutout in the plate of the secondary movement allows it to mesh with the secondary crown wheel. An additional wheel is needed between the crown wheel and barrel, since the secondary crown wheel turns in the opposite direction of the primary crown wheel.

The smaller watch also uses a more elaborate regulator arrangement, a screw that passes through the primary movement and connects to a cam. Turning the screw moves a lever (blue) back and forth which then moves the regulator on the secondary movement.

The screw for the secondary movement’s regulator has scars around it, probably from wayward screwdrivers. Also note that forty is spelt as “fourty”, something you still occasionally see on Swiss watches today.

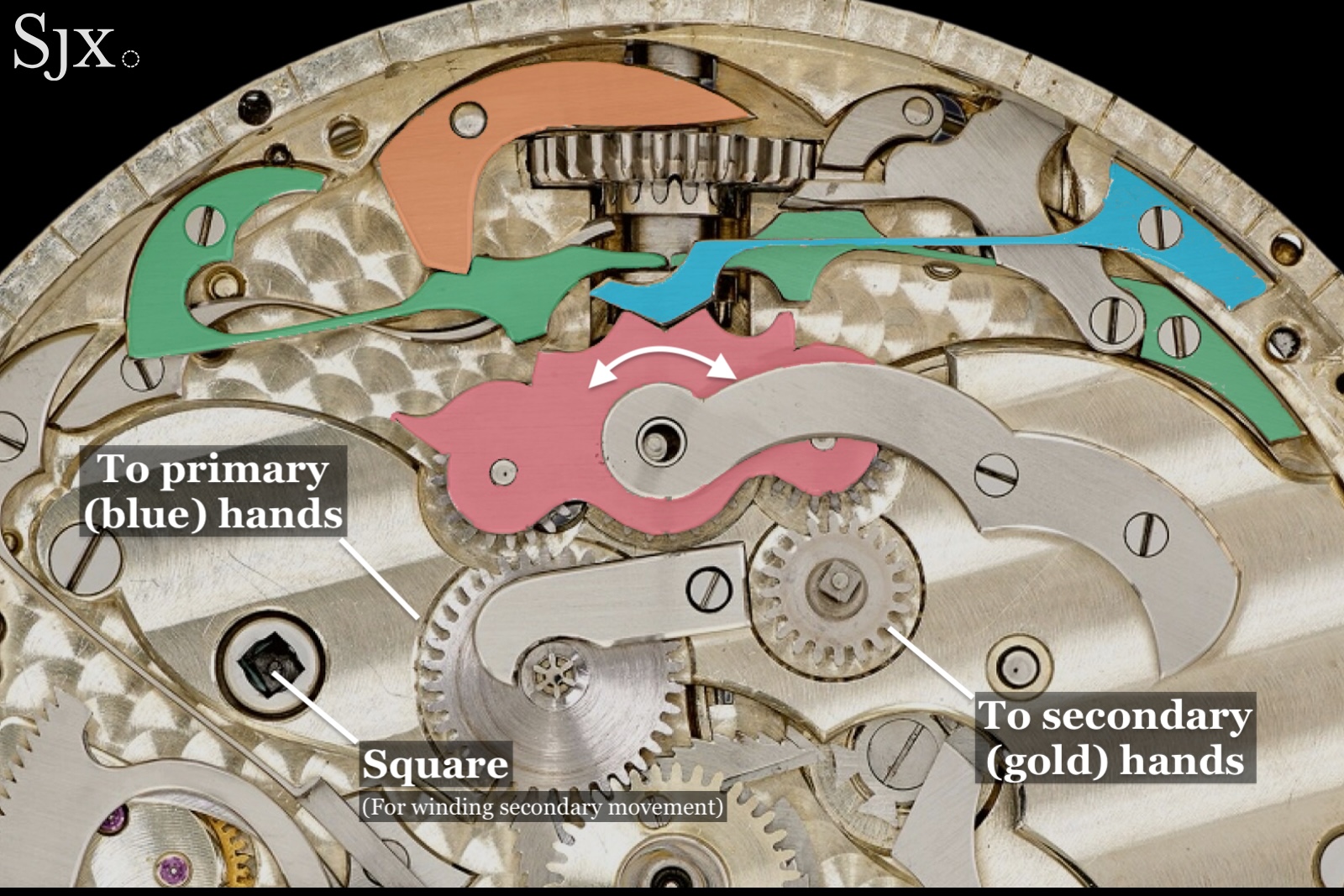

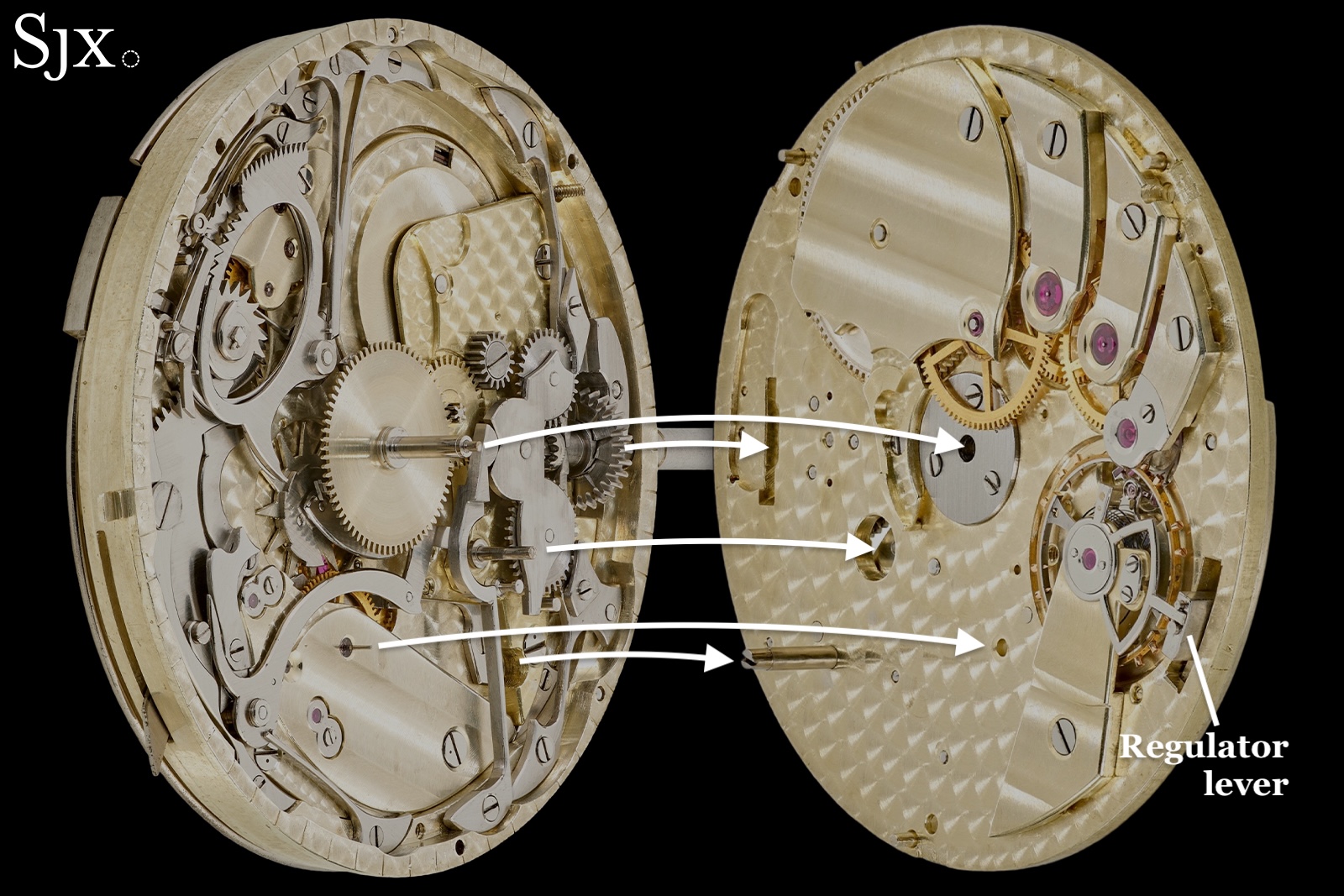

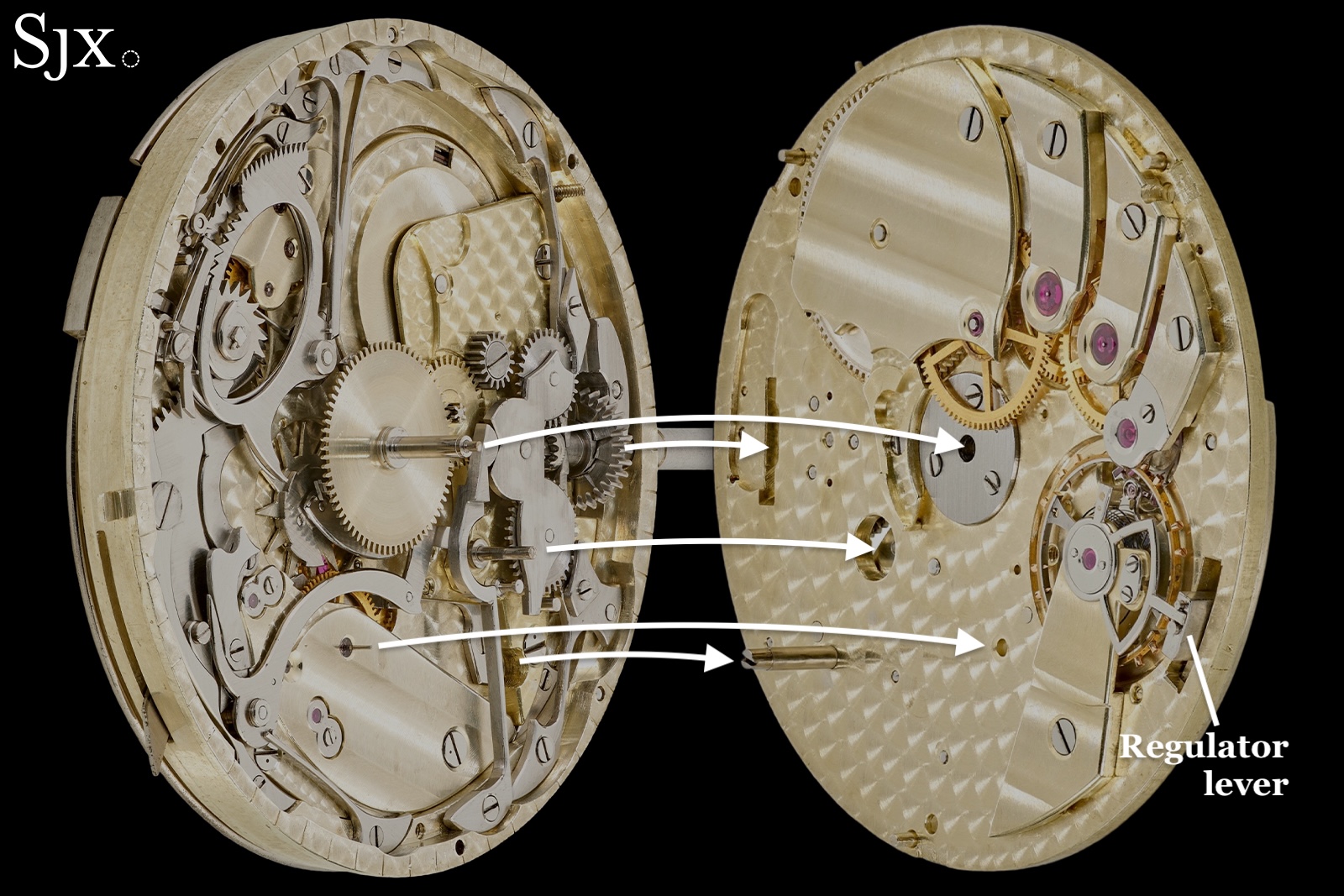

The composite of the movement photos provided by Sotheby’s show the movements as if folded open like a book.

The arrows show how the primary movement passes through the secondary movement. The first arrow (from top to bottom) is for the primary hour and minute hands. Just below is the crown wheel, then the hand setting connection, seconds hand, and finally the connection of the regulator. You will also notice a trio of locating pegs on the secondary movement’s perimeter, and corresponding holes on the primary.

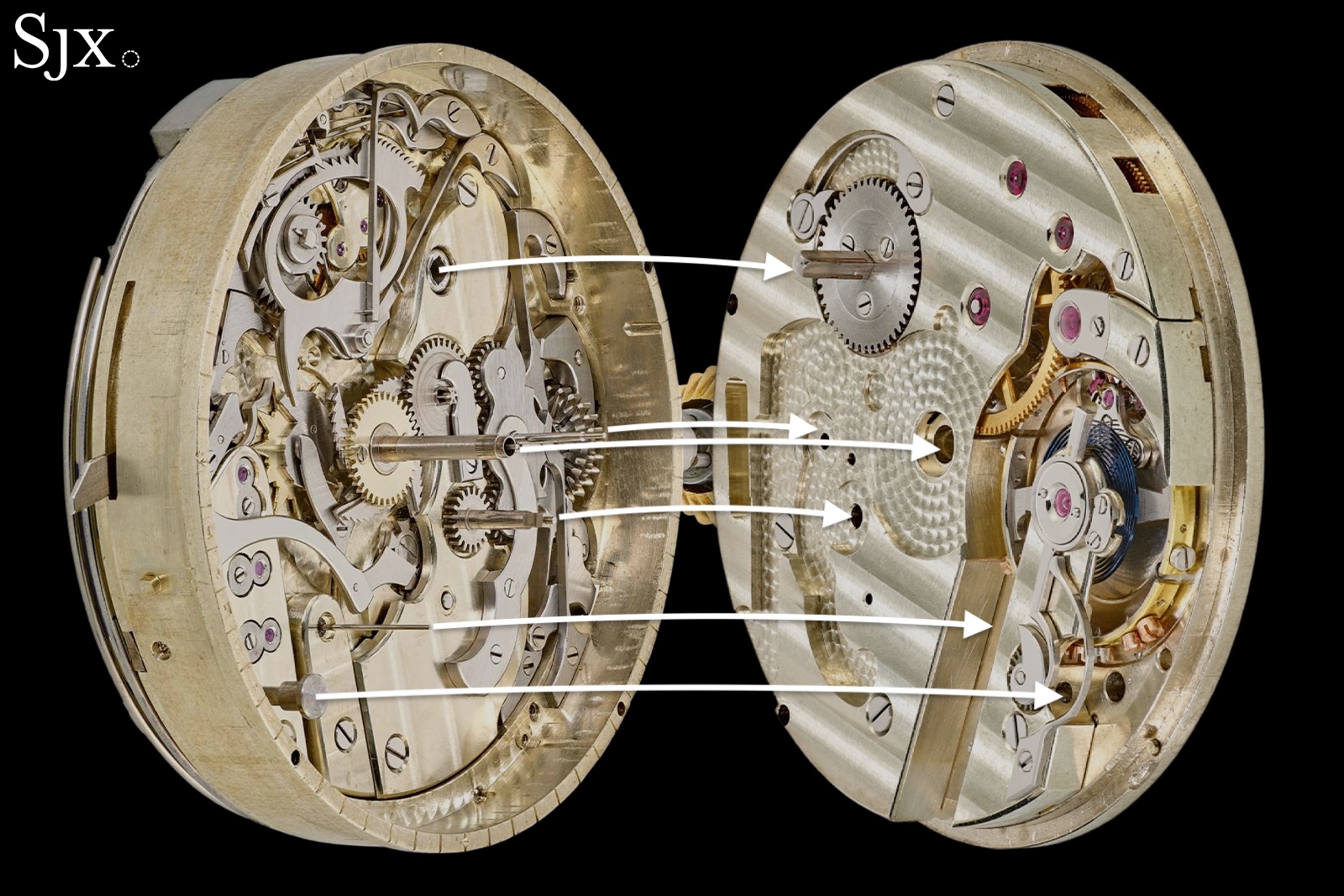

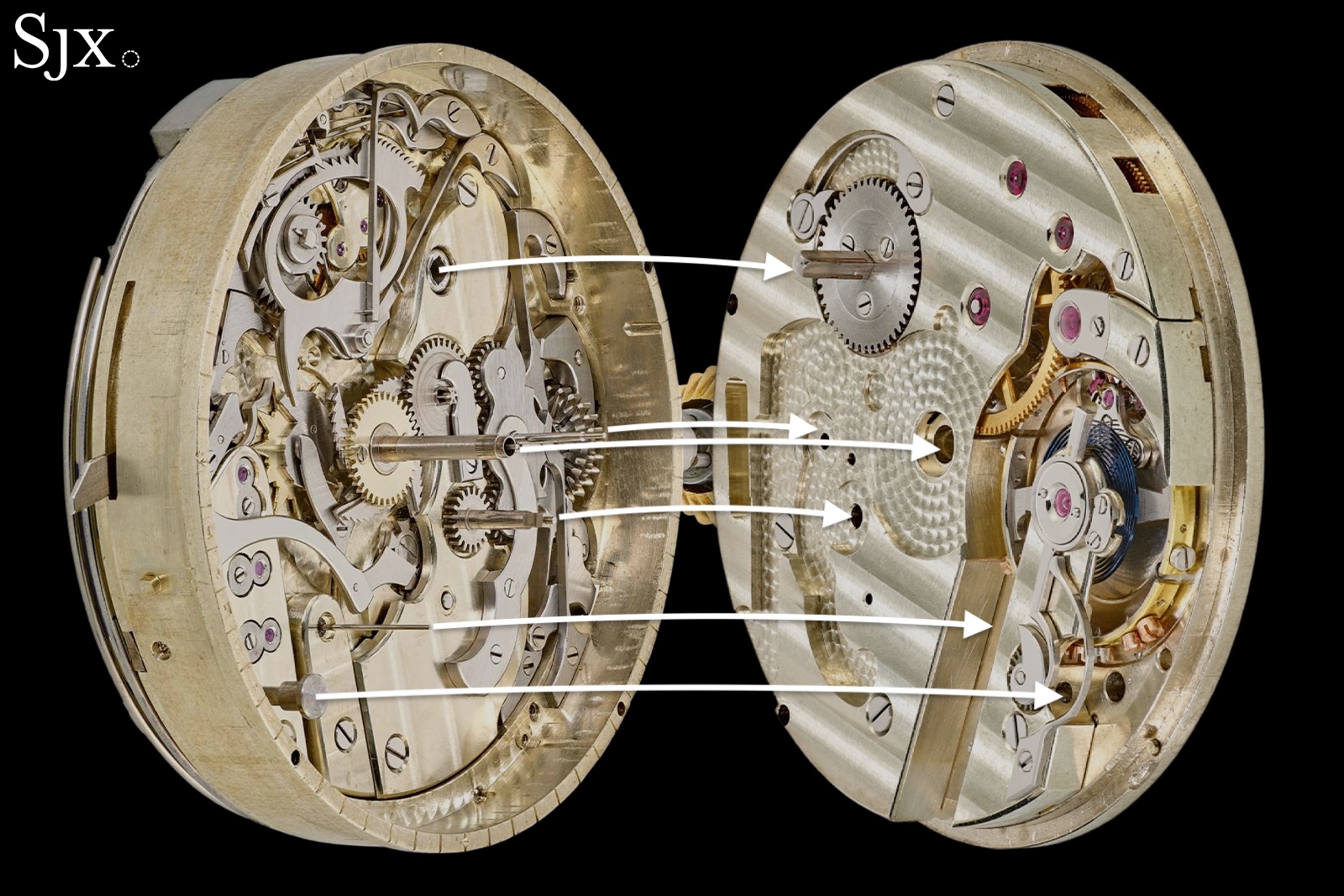

In the larger watch, the secondary movement is essentially a key-wound calibre, and the primary movement holds the key. It uses Sylvain Mairet’s differential winding system, which is found in many high grade two train pocket watches of the time, such as clock watches, trip repeaters or those with independent seconds. There are two reverser wheels, one is connected to the barrel of the primary movement, while the other has a square hole that a square shaft (attached to the barrel of the secondary movement) slots into.

Both barrels only wind when the reverser wheel on top turns clockwise, this is an extra wheel between the crown wheel and the other, allowing each barrel to be wound individually. Since there is an extra wheel between the crown wheel and the reverser over the secondary barrel, turning the crown clockwise winds the primary movement while counterclockwise winds the secondary movement.

The composite images below illustrate the movements folded open like a book to illustrate how, from top to bottom, the winding square, minutes totaliser, hour/minute hands, seconds hand, and regulator interface.

The Patek Philippe double movement watches: no. 197’589 (lot 34) has an estimate of US$300,000-500,000, while no. 197’590 (lot 33) has an estimate of US$500,000-1.0 million. For more, visit Sothebys.com.

Back to top.