Five Things to Know About Bovet, Straight From The CEO

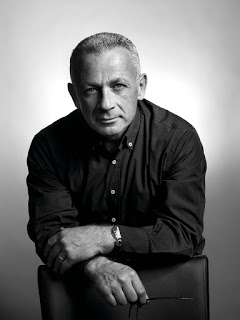

An interview with Pascal Raffy.

Bovet chief executive Pascal Raffy is a man passionate about watches who bought a watch company, turning it into a manufacture specialising in high-end complications housed inside its patented convertible case.

A lawyer by profession, Pascal Raffy acquired Bovet 1822 in 2001. Based in Fleurier, also the home of Parmigiani and Voutilainen, Bovet was then merged with Swiss Time Technology (STT), the dial and movement manufacturer Raffy took over in 2006. Bovet’s history, however, stretches back centuries.

Founded in 1822, Bovet was established to manufacture high-end timepieces for the booming market in Imperial China. One of the most prominent names in China in the 19th century, Bovet’s lavishly enamelled pocket watches, often set with pearls, are rare and valuable today. That distinctive, ornate aesthetic is echoed in the style of contemporary Bovet timepieces, the product of Raffy’s vision for the company.

Bovet is an independent, haute horlogerie watchmaker that makes 3000 only watches a year

“When you have a wedding, you go to your tailor, you take your time. He even asks you to come back two, three, four times. That’s normal, because you are doing something handmade. True luxury is only three things: a clear identity, very little quantities, and handcrafted. If you have what everybody has, then it is not luxury. If it is made in [numbers] of more than 8000 to 9000 timepieces per year, it’s not luxury; it is an industrial process. Of course that luxury in little quantities is more expensive because for the same number of employees you do one-tenth of the quantity.

Take your loupe, to every single detail – anglage, polishing, engraving, miniature paintings – you must find perfection. Or nearly perfection, knowing that true perfection does not exist. Every single component is hand-finished, polished, angled, engraved. And I sign my certificates, every single one, by hand. The 3000 timepieces we do per year we handcraft. What is the capacity of Bovet? Six thousand pieces per year. Do I want to go above that number? No. Perhaps it’s the luck of being independent. You don’t have to report to your shareholders, you must give them 20% dividend every year.”

.jpg) |

| Detail of a hand-engraved Bovet dial |

Bovet is vertically integrated manufacture that produces many of its own movements, and also supplies other brands with movements and parts

“Is it important to be able to handcraft your own movements? Yes, to sustain one thing: passion. As my general manager says, the big luck we have in Bovet is that the owner is not a watchmaker. I made a decision to offer my collectors more than what they are paying for, because I am a collector. And how do I do it [and remain viable]? It’s a mixture of passion, wisdom and perhaps good management.

When I took over the facilities, some brands were clients of Bovet. I respected the existing clients, but after [the contracts ended], I wanted to concentrate on my babies. And we respected every single existing contract, in dials, movements and hairsprings. Nowadays we still have a few of them, not as a necessity, but to behave as gentlemen.”

Bovet’s signature is the pocket watch inspired-Amadeo convertible case that can be swiftly transformed from wristwatch to pocket watch to desk clock

Referring to the Amadeo Braveheart tourbillon: “You have a baby here with six patents, from the bow to the crown to the dial to the cage – everything is symmetrical. The Amadeo system is a patent; the fixed bridge for the tourbillon is a patent.

|

| Amadeo Fleurier Braveheart |

By pressing [on the buttons in the bow], you can open [the Amadeo case] smoothly, and you can wear it on the other side. It’s the most unique expression of time on the market. This case is 130g of platinum. This angle [for the stand for the watch as a desk clock] took seven years of study. I put my timepiece here [on the desk], and I can read the time without moving.”

Bovet specialises in tourbillons, because Pascal Raffy loves them

“I love tourbillons because I am a man of passion and I need to see the heart beating. Not because it’s the fashion. And on top of everything, [the Amadeo convertible case] is the true meaning of tourbillon, which was invented for a pocket timepiece, not for a wrist timepiece. I need a timepiece to talk to me. If a timepiece from another house talks to me, I collect it. I’m not closed because I’m the owner of Bovet. I need to find substance and true values.”

.jpg) |

| A Bovet tourbillon regulator |

Bovet was one of the first Swiss watchmakers to arrive in China, and the recent economy slowdown there has had little impact

“Never has Bovet left Mainland China since 1822. But have we reached the position in China that I am dreaming about? No. Am I sad? Not at all. Because when I took over Bovet, I promised myself that I would restore the brand, and it took me 14 years.

To accommodate the demand from China you have to be prepared. It’s exactly what we did for the last 14 years. So in 2016 we will return significantly to Mainland China. The big luck we have is that 80% of our turnover is done in the other 43 countries [we are in]. I’m not in a position where Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan is 70% of our turnover. Because of that, the way we consider Mainland China is much more serene. It is a bonus; it’s not a pressure at all. When we go back, we go back home.”

Back to top.

.jpg)