Hands On: Breguet Equation of Time Pocket Watch No. 2492

Traditional and transitional.

A rare Breguet pocket watch with retrograde perpetual calendar and equation of time illustrates the evolution of the house from its founder’s era to the early 20th century, blending historical motifs with modern concessions. Made in 1932, Breguet No. 2492 is one of just four known examples from a series of equation of time movements produced over nearly five decades by the legendary workshops of Victorin Piguet.

In short, it’s a watch with one foot in the 19th century and one in the early 20th. The transitional nature of the watch evidently resonated with collectors, as the watch recently sold for CHF241,300 at Phillips’ Geneva auction in November, some 20% above its high estimate.

Context

It might be surprising, but Abraham-Louis Breguet’s unexpected death in 1823 had no immediate effect on the firm’s output. The firm produced well over a hundred watches each year, which required a staff of skilled workers, as well as A.-L. Breguet’s family, who understood what a Breguet watch was, and could build one without being managed by the man himself.

However, with the old guard’s retirement, and general decline of Parisian watchmaking, things slowly changed. After the Breguet family sold the firm in the late 19th century, turning instead to the more lucrative business of aviation, the firm’s output strayed from A.-L. Breguet’s vision, abandoning Breguet’s signature design language for a medley of styles catering to specific markets.

During this time, the brand mostly finished generic Swiss ebauches, as well as occasionally restoring and reselling old watches from the firm’s better years. It still, however, remained a prestigious name, as evidenced by its lengthy client list of eminent names in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The 20th century bought a more sophisticated breed of collector, and renewed interest in A.-L. Breguet’s work, no doubt in part due to David Salomons’ seminal book Breguet (1747-1823), published in 1921. The brand began selling more watches with Breguet hands, Breguet numerals, coin edged cases, and engine turned dials. Breguet also enlisted Les Fils de V. Piguet, the formal name of the Victorin Piguet firm, to build specialised movements, with off centre time displays, perpétuelle winding, tourbillons, and retrograde perpetual calendars. And of course the firm also started selling wristwatches, then a novelty (but sometimes still very complicated).

Production of these watches spanned decades, with either 18”’ or 19”’ movements. The first known examples being No. 1648 and No. 2492 (the present watch) made in 1928 and 1932, respectively. Cecil Clutton, a collector and friend of George Daniels, bought watch No. 5026 new in the 1950s or 1960s, and Breguet sold the last known example, No. 4377, in 1977. It is hard to say how many exist – especially since one of the four known examples is not recorded in Breguet’s archives – but they are vanishingly rare.

Breguet No. 1648 (left) sold in 1928 and Breguet No. 4377 (right) sold in 1977. Images – Antiquorum

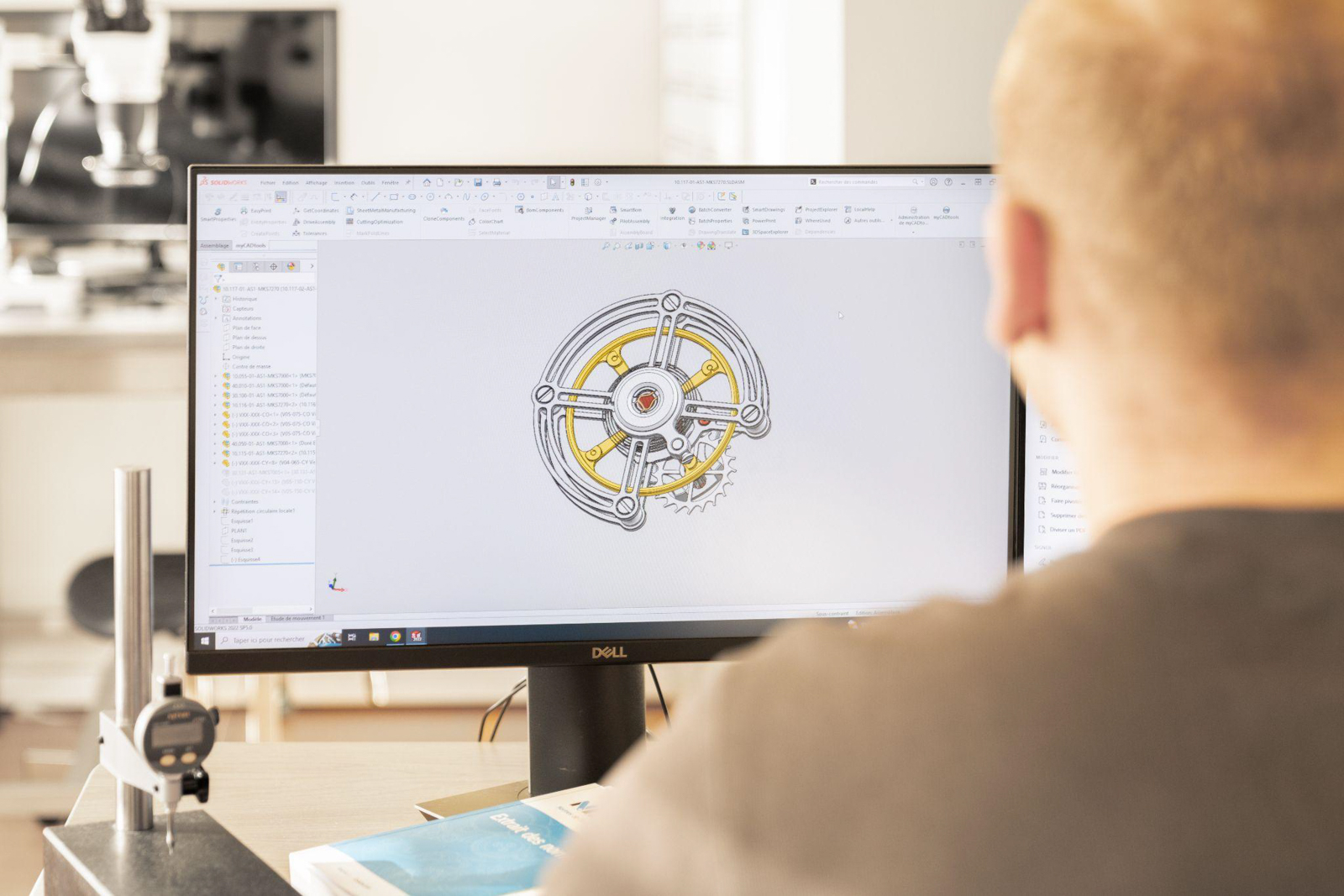

For the production of these watches, and indeed most of the brand’s complicated pocket watches produced during the 20th century, Breguet turned to the workshops of Victorin Piguet. A native of the Vallée de Joux, Victorin Emile Piguet (1850-1937) founded his own company in 1880 with his brother in Geneva. He returned to the valley in 1883 to establish a workshop in Le Sentier, which went by the name Les Fils de V. Piguet for most of the 20th century. His firm quickly became Patek Philippe’s go-to supplier for its most complicated or unusual movements, including the Henry Graves Jr Supercomplication, which would have been nearly complete when this watch was sold.

Breguet was another key customer, and Les Fils de V. Piguet developed bespoke movements and complications based on the brand’s history, such as bumper-automatic pocket watches as well as these retrograde equation of time watches. It is worth noting that the workshops of Victorin Piguet also constructed a run of similarly Breguet-inspired movements with instantaneous aperture perpetual calendars for Patek Philippe.

Images – Breguet, Phillips, Antiquorum

Despite the near-extinction of fine watchmaking during the wristwatch era that forced other complications specialists to adapt or die, Victorin Piguet’s grandson, Henri-Daniel Piguet (1904-1997) continued the tradition into the modern era. This was mostly at the service of Patek Philippe – with whom Piguet signed an exclusivity agreement to produce wristwatch perpetual calendar modules in 1949 – but also Breguet and others.

Case and calibre

During the mid-to-late 1760s, Jean-Antoine Lépine pioneered the flat, fusee-less style of watch movement using bridges rather than plates and pillars. This modern style of construction, which is still in use today, results in a much slimmer watch. A.-L. Breguet was an early adopter of Lépine’s approach, which he used almost exclusively later in his career (except for his tourbillons) making his watches remarkably slim for the time. While A.-L. Breguet was ahead of his time in adopting Lépine calibres for his movements, they had become industry standard by the time the present watch was created.

That said, while Lépine-style movements were already common in the early twentieth century when these watches were made, watch No. 2492 is illustrative of A.-L. Breguet’s propensity for doing things differently. For example, rather than using generic ebauches, A.-L. Breguet worked with his blantiers (located mostly in Paris and Switzerland) to develop bespoke ebauches, a practice that was key to the distinctiveness and diversity of his watches.

That tradition can be seen in action with the base movements of pocket watches like No. 2492, as well as the Breguet-inspired Patek Philippe watches mentioned earlier, which feature an off-centre “centre” wheel, which is responsible for the eccentric hour and minute hands that sit slightly below the centreline of the dial. Today this effect is often achieved using a dial-side add-on, such as a the perpetual calendar module found in the modern Breguet Classique Calendrier 7337.

The movement is styled and finished like a fine Genevois watch of the time. While not true to A.-L. Breguet’s original style, this look had broader appeal at the time that it was made and features many of the touches we now view at traditional, including finely ground Côtes de Genève striping, lavish anglage and a bright rhodium finish.

The movement represents the evolution of the house of Breguet in other ways as well. For one thing, it lacks a Breguet overcoil hairspring, found in most watches of the time, likely a concession to thinness. It’s also a complicated watch without a repeater, which was once the brand’s most popular complication; according to George Daniels, A.-L. Breguet built more watches with repeaters than without. That No. 2492 lacks a repeater speaks to the ways in which the world changed between the time of A.-L. Breguet and when this watch was made; the proliferation of gas and electric lighting meant most users could read the time around the clock without the need for a chiming complication.

The mixed metal chain reflects prevailing tastes of the Art Deco era. Breguet sold a number of mixed-metal watches during this period, and while this 51 mm Murat-style case is not one of them, the chain comprises yellow and white gold links, capturing the spirit of the time. The mixed metal aspect means these chains can be paired with white or yellow gold cases interchangeably. For example, another Breguet from the same collection, a white gold minute repeating perpetual calendar, has an identical chain.

The calendar

To account for the varying lengths of months, a perpetual calendar must skip up to three days at the end of some months. Until the mid-19th century, continental watchmakers usually accomplished this using a retrograde date display. Advantageously, a retrograde date can return to the first from any arbitrary date, making it ideal for perpetual and annual calendars. A.-L. Breguet used this approach in two perpetual calendars (No. 92 and 160) and one annual calendar (No. 1230), though the calendar works were actually made by a close collaborator named Lallemand.

Importantly, the calendar mechanism of the present watch, and its siblings, was executed in the style of Breguet, rather than the more recent retrograde perpetual calendars made by the Swiss during the 19th century, such as those by Marius LeCoultre.

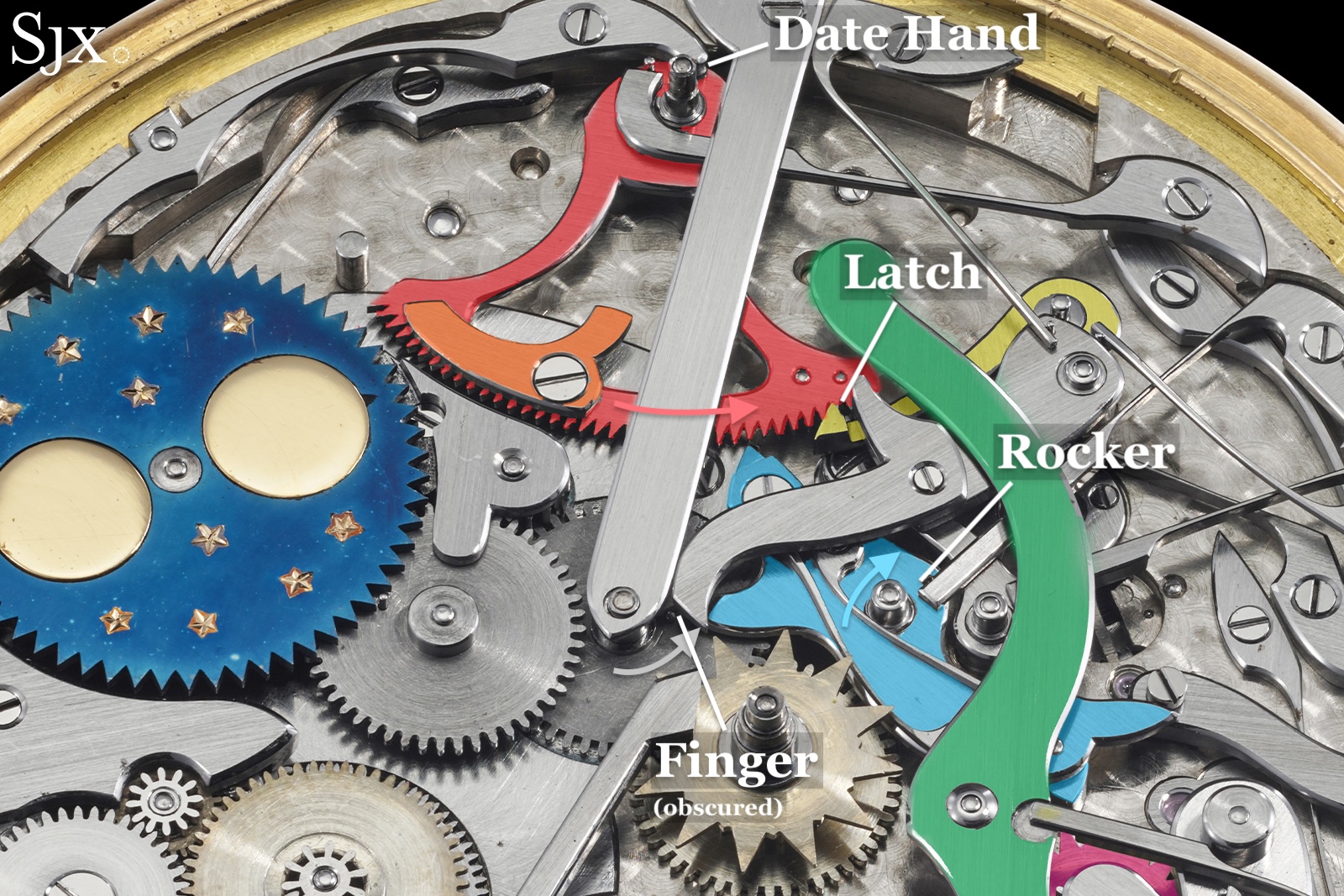

A 31-tooth rack (red) displays the date. The rack is held under tension by a spring, which pushes it to the left. Every 24 hours, a finger causes a rocker (light blue) to pivot slightly, which advances the red rack by one tooth to the right, which is held in place by a latch (yellow).

Image – Phillips, annotated by the author

On the other side, the blue rocker also advances a star wheel (magenta) by one tooth, which turns the equation cam through a train of wheels. The equation cam makes one rotation each year, and is read by a lever and displayed by the hand at six o’clock. This displays the difference between local mean solar time, as kept by a clock, and apparent solar time, as measured by a sundial.

Somewhat confusingly, this can be expressed as apparent solar time relative to mean solar time, or mean solar time relative to apparent solar time, but the former is the norm for watches and clocks. So, here the equation segments reads as the sun being about four minutes behind the watch, which is correct for early July.

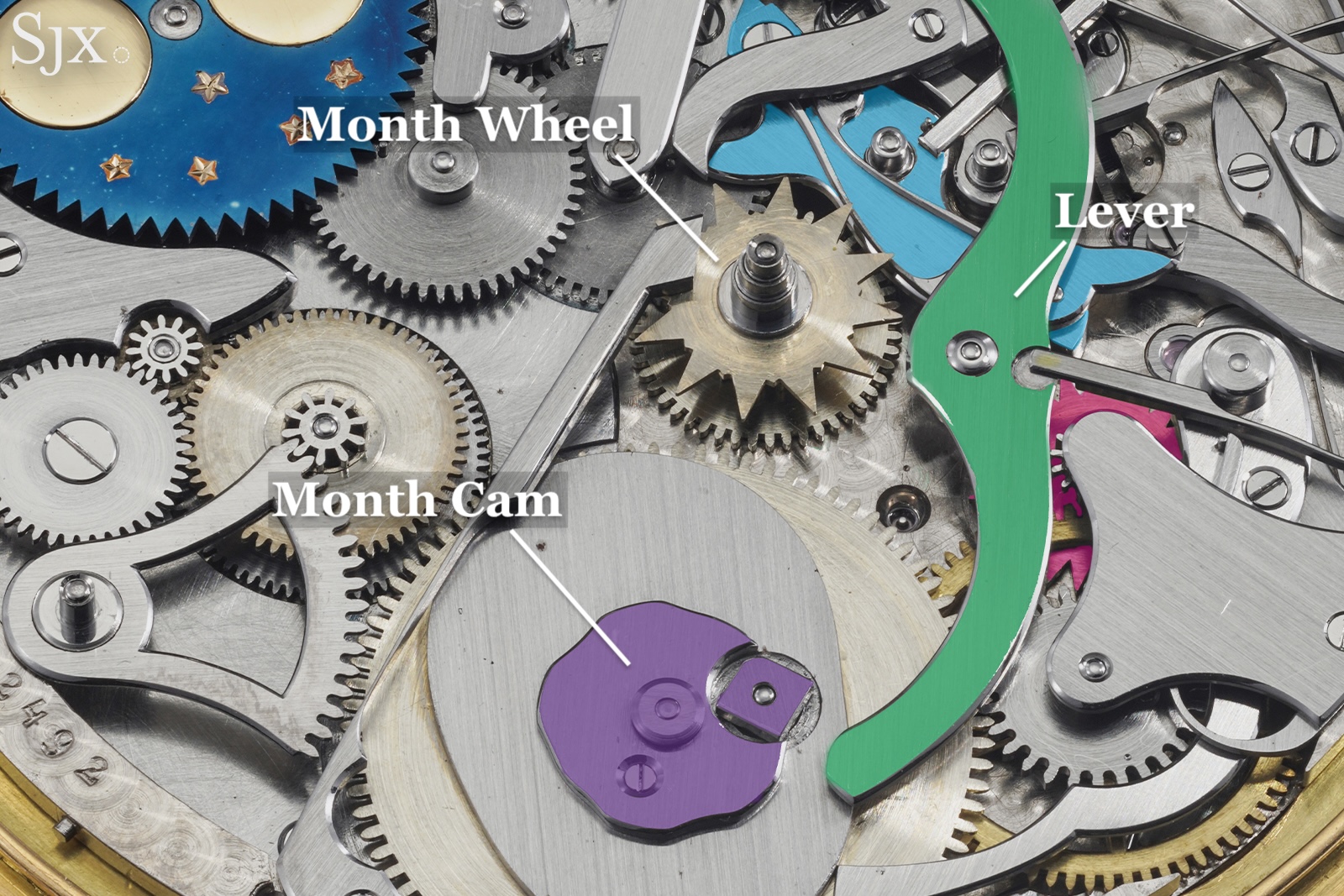

The month cam sits on top of the equation cam. All twelve months are represented, with the valleys being months with 31 days, and the peak being February with 28 or 29 days. An unseen Maltese cross mechanism turns the February piece by 90° each year, to account for leap years. There is also a 12-toothed month wheel coaxial with the cannon pinion that displays the month, but isn’t directly connected to the month cam as it is in most perpetual calendars.

Image – SJX composite/Phillips

As the rack approaches the end of the month, the release piece (orange) pushes against a lever (green), which pivots towards the month cam (purple) until it makes contact and can move no more. This happens after 28 to 31 days, depending on the position of the month cam.

Once the lever can no longer yield, the next time the rack tries to advance, the release piece (orange) moves instead, pivoting to lift the latch (yellow) to allow the rack to fly back to its starting position once the rocker (light blue) pulls back. The release piece also pivots another lever, which nudges the month wheel forward.

Image – SJX composite/Phillips

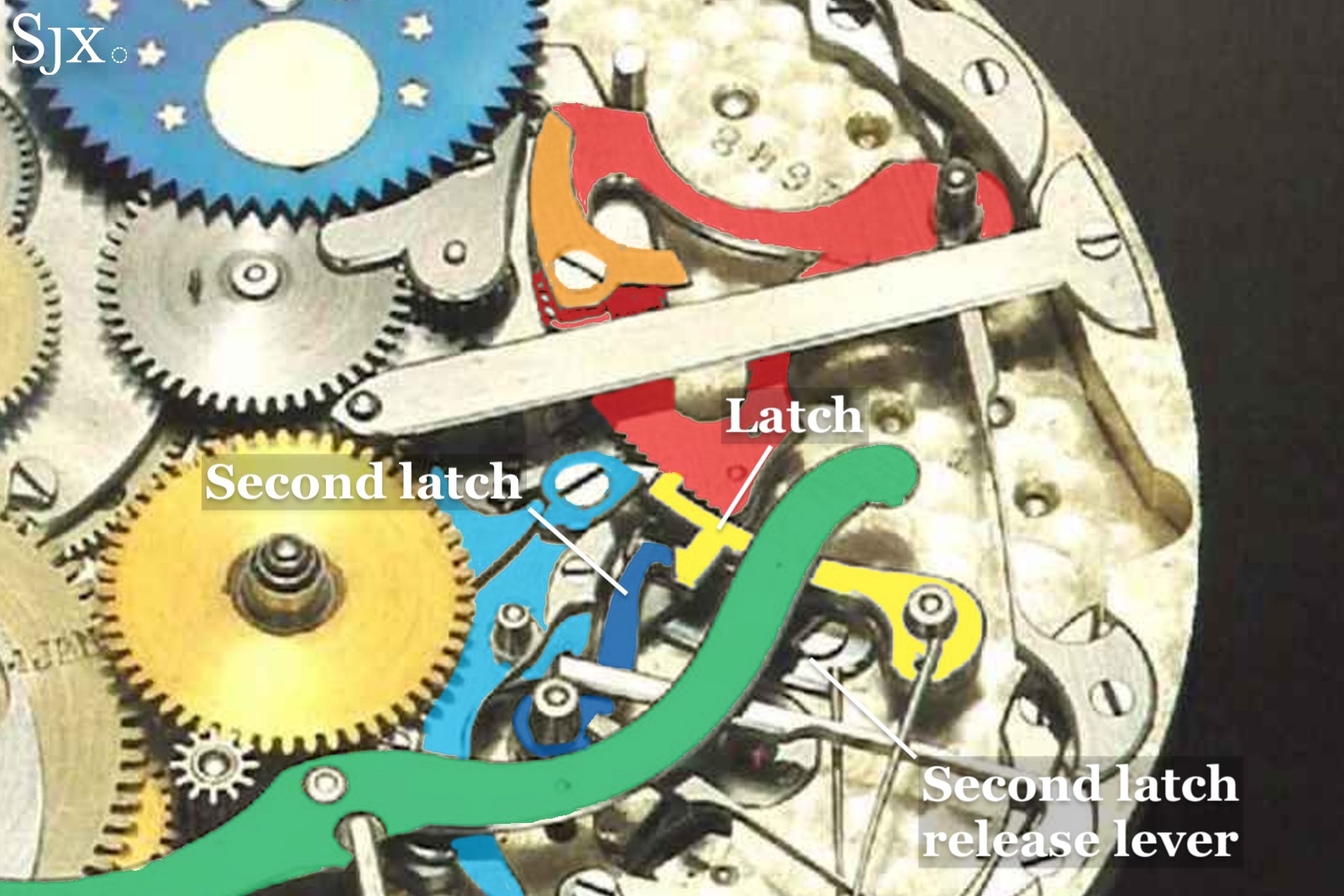

Once lifted, the latch (yellow) is held in place by a second latch (dark blue), which is obscured from view in this watch, but clearly visible in No. 1648. This ensures the rack can return to the first. Later, a barely visible release lever underneath frees the latch (yellow) from the second latch (dark blue).

Image – SJX composite/Antiquorum

Setting the perpetual calendar is quick and easy if the watch has been stopped for only a few days or weeks. Pressing the pin-pusher corrector in the case band near six o’clock pivots the light blue rocker, advancing the date, month and equation of time all at once. A second pin-pusher near 11 o’clock sets the moon phase, which is independent of the perpetual calendar. You must be careful not the overshoot though, as the calendar can only be adjusted forward; turning the hands counterclockwise across midnight only affects the moon phase, leaving the date unchanged.

The source material

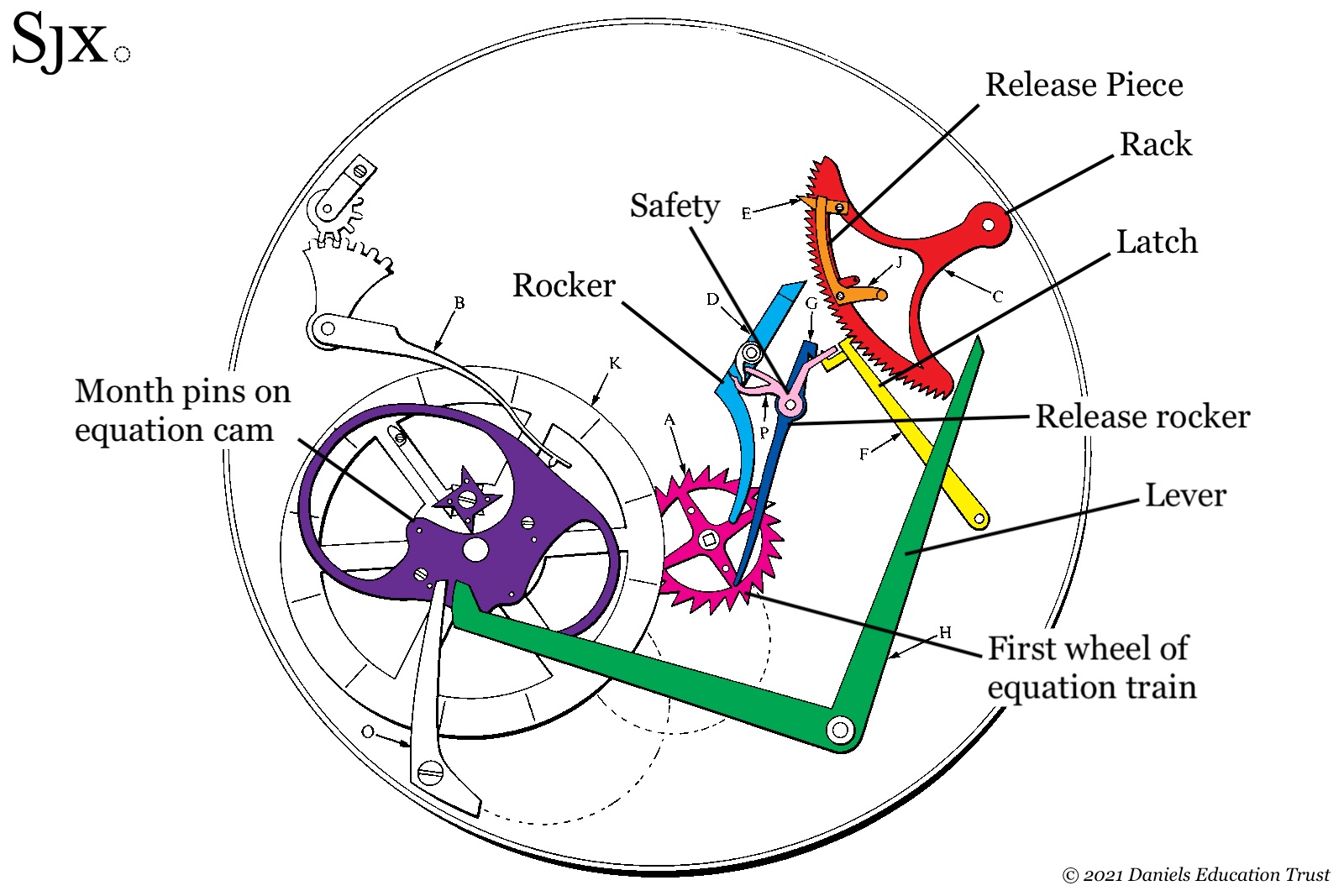

Conceptually this is the same as Breguet’s historic perpetual and annual retrograde calendars. Below are the calendar works of No. 160, showing how similar this watch is to Breguet’s most famous watch, even a hundred years removed. Here, the first wheel of the equation train (magenta) turns counterclockwise and carries pins to actuate the rocker (light blue), a release rocker (dark blue). It also advances a day display (not shown).

The perpetual calendar works of No. 160 as depicted in the Art of Breguet by George Daniels, annotated by the author. Notice the month cam is replaced by a series of pins on top of the equation cam. Image – The Daniels Education Trust, annotated by the author

It adds a safety (pink) that blocks the latch (yellow) from being released except when the rocker (light blue) advances the rack. During this window (when the safety is disengaged) on the last day of the month, the release piece (orange) nudges the latch (yellow) just enough for the release rocker (dark blue) to grab it, and hold it in the released state. This allows the rack to return to the first of the month once the rocker (light blue) is no longer acting on it. Finally, a pin on the first wheel of the equation train (magenta) pivots the release rocker (dark blue), which lets go of the latch, allowing it to fall back into place.

Back to top.