Hands On: Breguet Four-Minute Tourbillon No. 1890

The best watch by the best watchmaker.

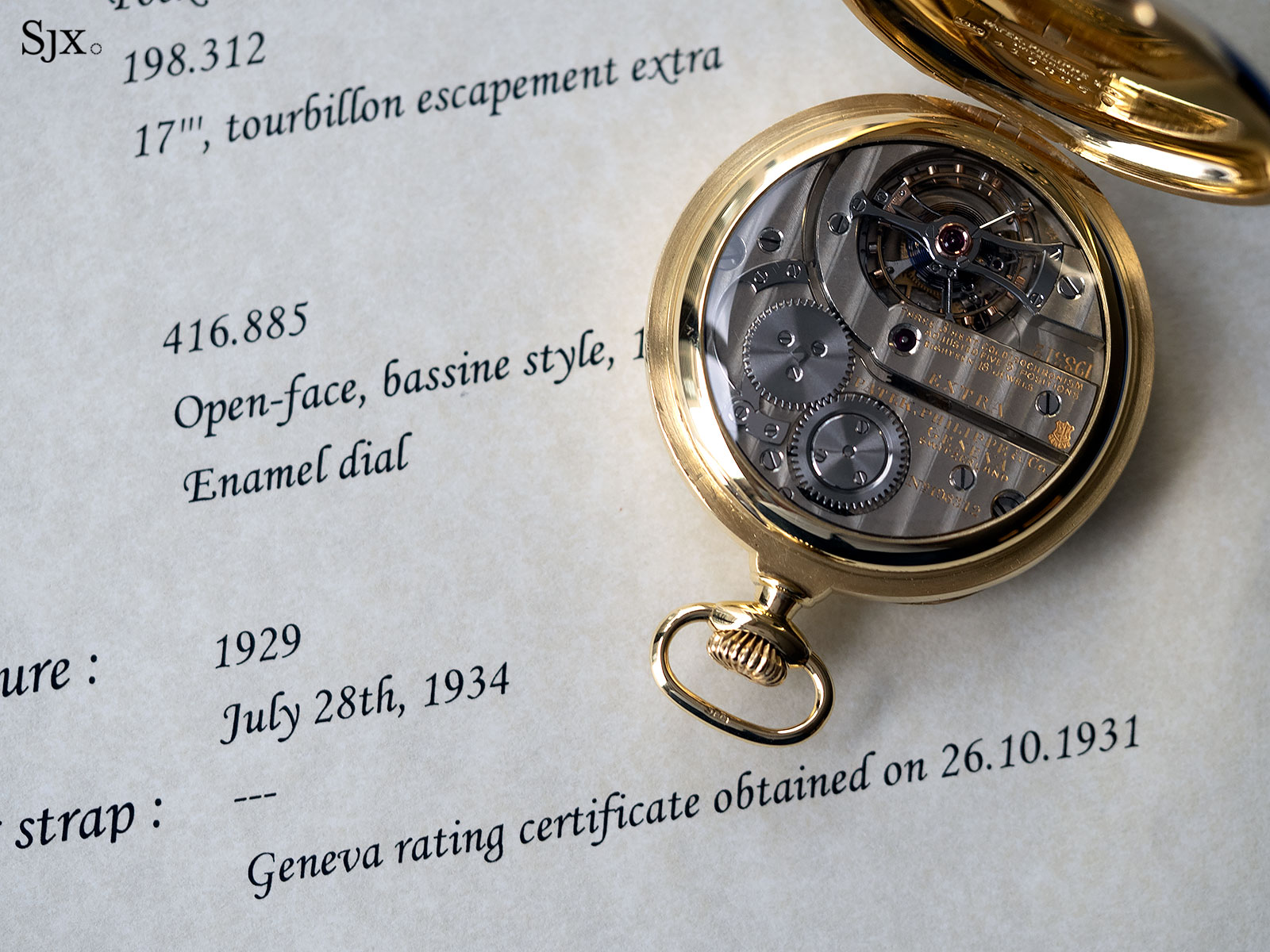

In the coming weekend, one of the most important watches of this auction season will go under the hammer at Sotheby’s Breguet’s 250th anniversary thematic sale November 9 – Breguet no. 1890, a pocket watch with tourbillon and natural escapement made by the firm by Breguet while Abraham-Louis Breguet himself still helmed the company.

The gilt dial with a regulator-style layout might seem familiar – the recent Classique 7225 reproduces this dial design. In fact, Breguet no. 1890 isn’t the only watch in this style; it belongs to a series of pocket watches all equipped with a four-minute tourbillon and échappement naturel from the early 19th century that were among the finest watches of the time.

Breguet built just eight four-minute tourbillons with natural escapement, all of which thankfully survive, and only three with gold dials. King George III ordered the most famous example – almost identical to this watch – during the Napoleonic wars. For context, that would be like Churchhill (who owned a Breguet himself) ordering an A. Lange & Söhne watch during the Second World War. As such, it was signed Recordon, Breguet’s London agent, to disguise its French origins.

Whirling About Regulator

Almost 225 years ago, the French Ministry of the Interior granted A.-L. Breguet a patent for his most famous creation, the tourbillon – a clever exercise in lateral thinking.

For a mechanical watch to keep the same time across all vertical positions the combined balance, staff, roller, collet and even balance spring must be as close to perfectly balanced as possible – to say nothing of the rest of the watch – which is challenging even with today’s modern hairsprings and specialised machines.

His invention rotated all the components most relevant to timekeeping along the same axis as the balance over a short period, meaning, theoretically, any arbitrary vertical position is the same as any other, when measured over a few minutes or more.

Interestingly, Breguet’s original patent for the tourbillon, and nearly all modern-day tourbillons, have a one minute period of rotation. However, most of the approximately 35 tourbillon pocket watch watches built during Breguet’s lifetime (and also tourbillon clocks and a chronometer) were of the four or six-minute variety, which reduces the load exerted on the mainspring.

Later, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th century, the tourbillon became associated with high performance timekeepers, in part because it was a natural fit for chronometry trials using the Plantamour rating system, which emphasised consistency across positions.

Today the tourbillon has been successfully industrialised in Switzerland and China, and more tourbillons are built in a single day, even by a single company, than during A.-L. Breguet’s entire life.

A Patek Philippe tourbillon tested by the Geneva Observatory.

The Watch

The watch going on the block at Sotheby’s is something of a celebrity, featuring prominently in the book Watches by Cecil Clutton and George Daniels. Clutton, the penultimate owner of this watch said “daily wear regularly shows a maximum variation in daily rate of five seconds, but generally very much closer, seldom exceeding two seconds.” While not remarkably impressive by today’s standards, the watch was already 150 years old at the time – over two centuries old now.

The dial is immediately recognizable the as the inspiration for the modern company’s recent ref. 7225. The engine turned dial is solid gold with à grains d’orge – or barley corn – pattern and held in place by a single blued screw. All markings are engraved into the dial and filled with black wax, similar to the coveted champlevé enamel of some midcentury Swiss watches.

A cartouche at 12 o’clock proudly announces the presence of a Regulateur à Tourbillon or tourbillon regulator, only a few dozen of which existed at the time. Two seconds dials flank the main, and what appears to at first be a repeater piston in the crown stops one of the two seconds hands – stop seconds remains a rarity in today’s tourbillons. This “observation seconds” system involves a rudimentary vertical clutch.

Image – Sotheby’s

The exaggerated size difference between the Breguet style hour and minute hands follows the same philosophy as later regulator clocks, making confusion between the hours and minutes impossible. Both hands are set with aid of a key by a square in the centre.

Breguet’s books log the sale of this watch to Frédéric Frackman in May of 1809. Frackman was an agent of Breguet in Russia – an important market for the firm then and now – not the end customer.

The first owner was Count Alexey Razumovsky. In addition to Breguet’s usual double secret signatures either side of 12 o’clock, the dial is also signed “Comte Alexis de Razoumoffsky” between eight and four o’clock. This is the only known Breguet with a customised secret signature.

Just below, the power reserve indicator, which is always useful on a precision timekeeper, ideally it should me wound every 24-hours for best timekeeping. Though the watch should run about the same at any level of wind due to the chain and fusee.

Constant Force

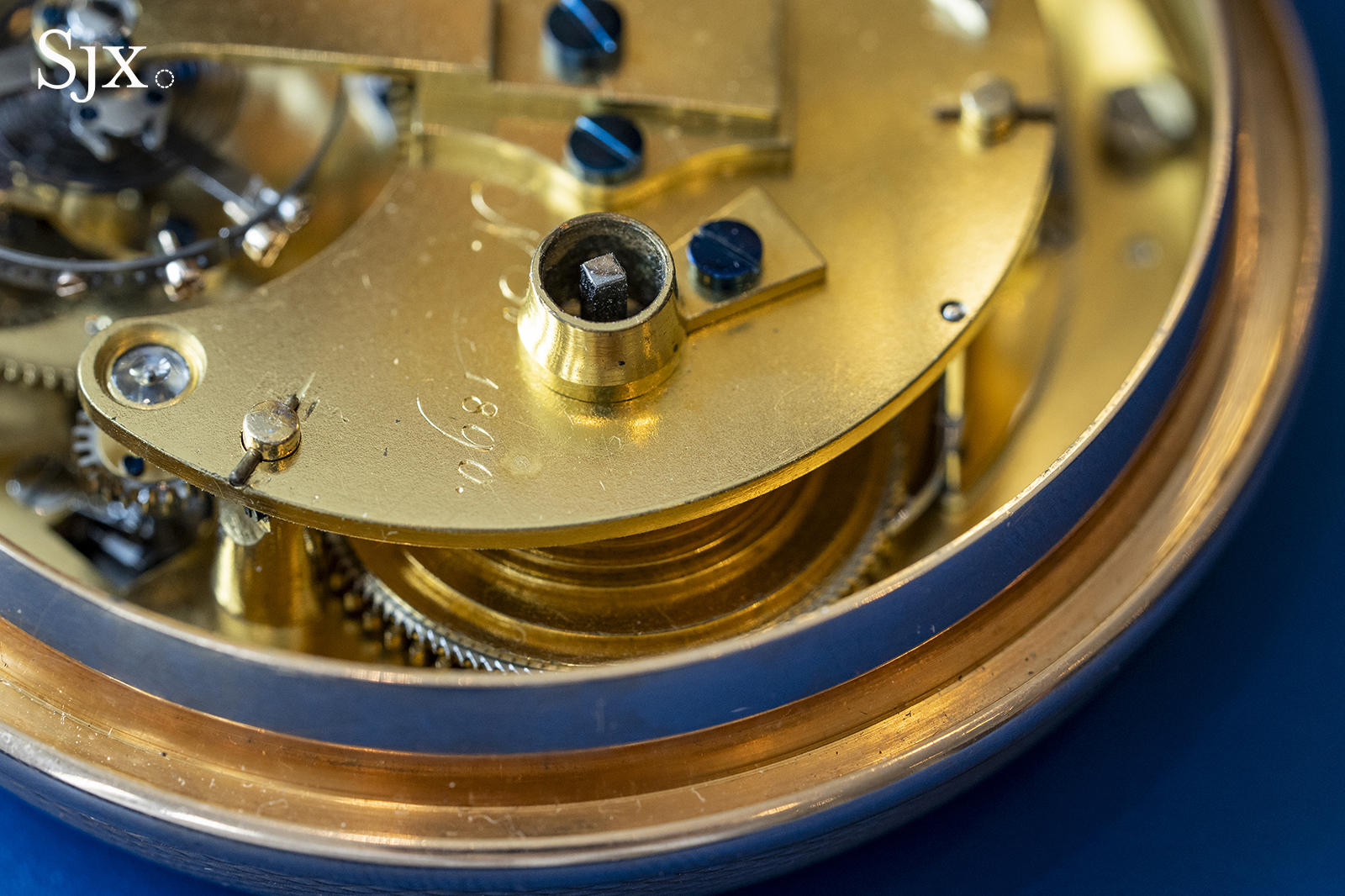

The chain and fusee system resembles a bike chain in appearance and function, essentially changing gears as the watch winds down to maintain even torque. While already challenged in watches by better mainspring designs and materials during Breguet’s time, the chain and fusee survived all the way into the middle of last century in marine chronometers.

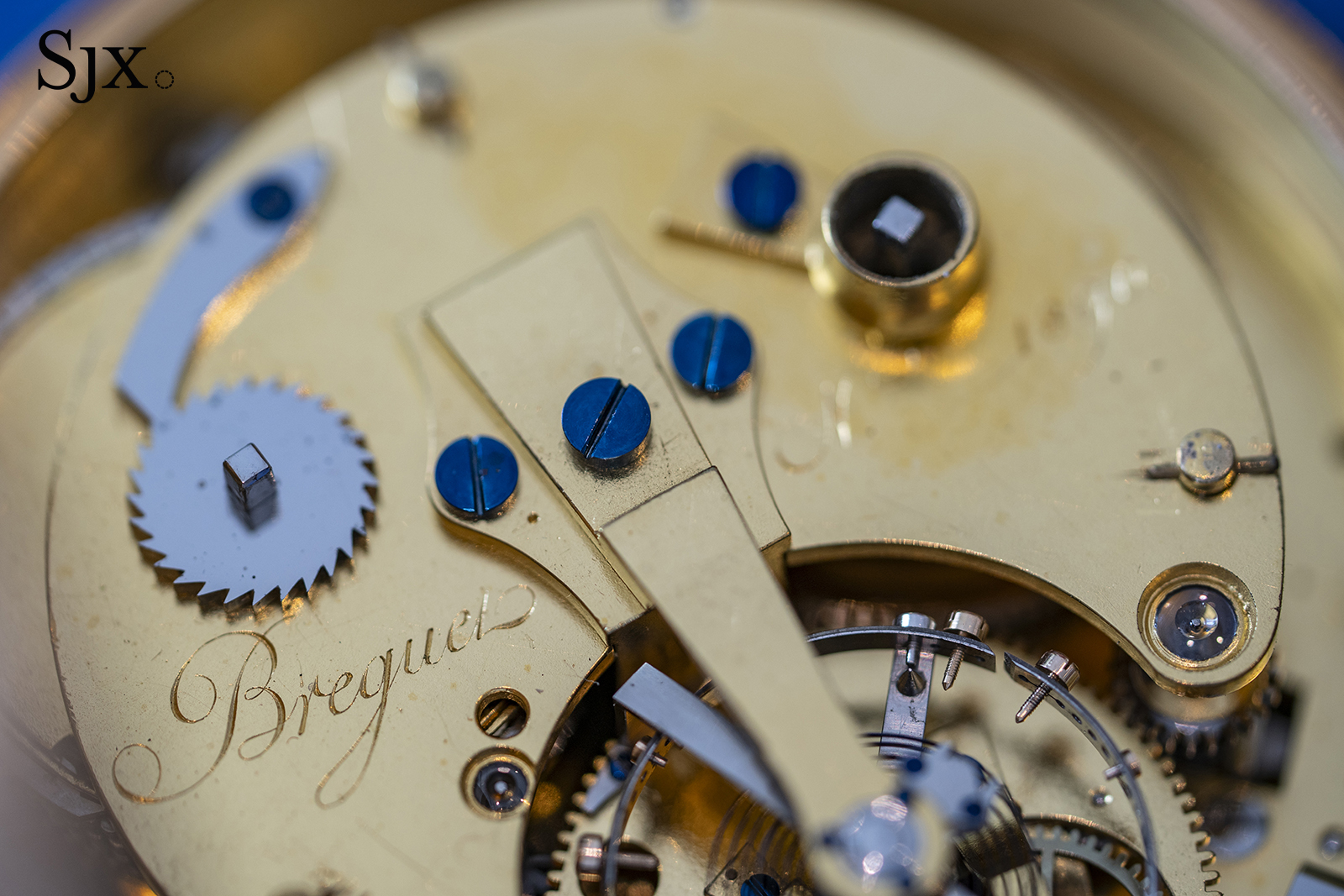

The movement uses pillar and plate construction, with its origin in clock movements, which was also retained in marine chronometers. Pins fasten the guilt three quarter plate to the pillars, instead of screws.

Each of the hundres of parts that comprise the chain were stamped out on a hand operated press. Obviously no one would do that today.

Unlike most verge fusee watches, which falter during winding, fusees of the era had the additional refinement of “maintaining power” by way of a small spring that takes over momentarily to drive the train during rewinding – it stores a few minutes of power in total. The silver tone wheel at the base of the fusee is the maintaining ratchet wheel.

The winding square.

Also like a marine chronometer, there are two squares on the back. The winding square sits on top of the fusee, while the setting-up square atop the barrel allows the watchmaker to tension the mainspring – never touch this.

The set-up square.

The dust cover only allows access to the correct square, and the watch should be wound with the dust cover closed to avoid mistakes. An arrow serves as a reminder that fusee watches (usually) wind counter clockwise.

Bifurcated Train

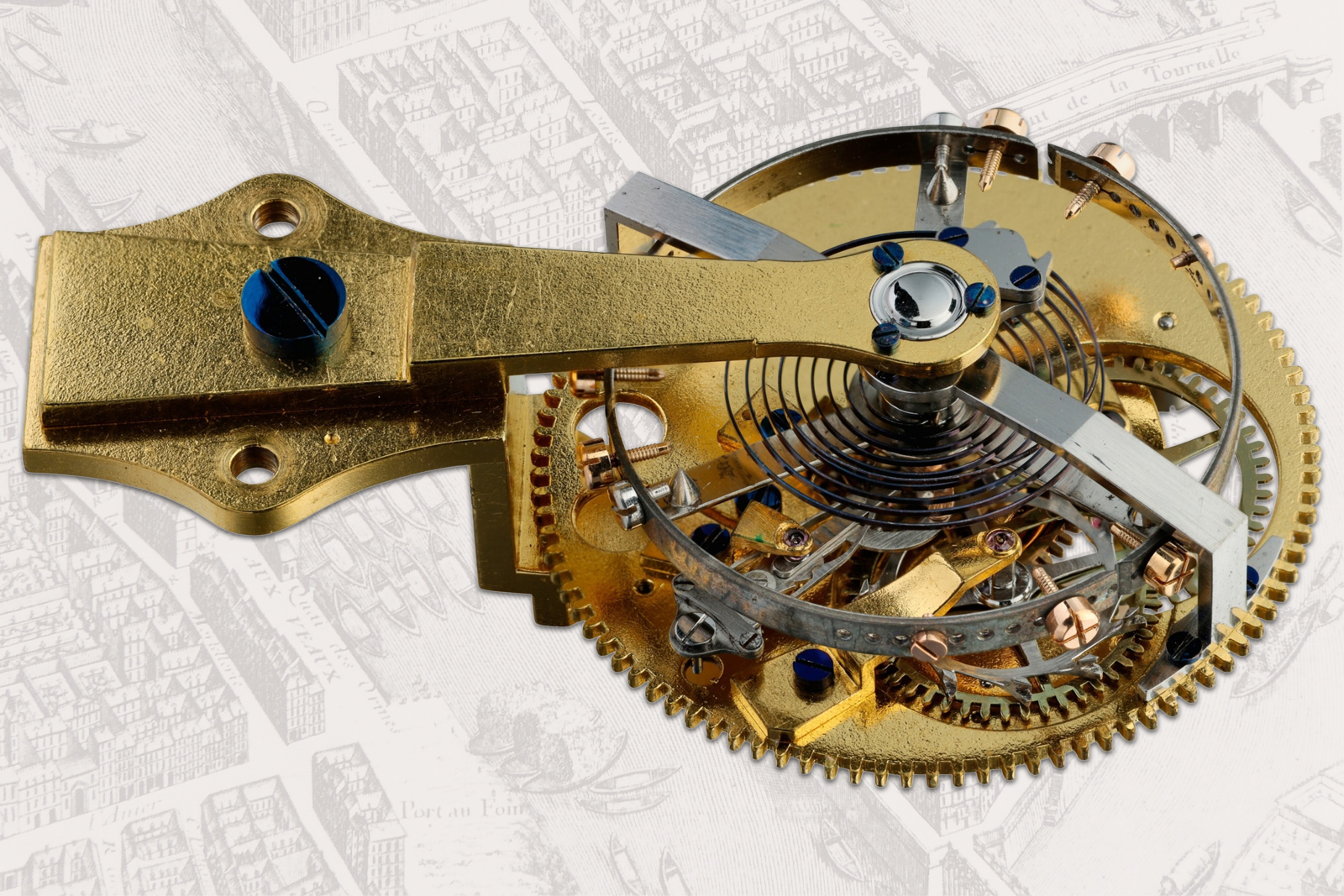

The fusee director the centre wheel, but after that the flow of power is hard to track as it occurs on the dial side, like a Chronometre Souverain. The left pinion carries the running seconds and drives the four minute tourbillon, which in turn drives the pinion carrying the stoppable seconds hand.

This early natural escapement doesn’t have two escape wheels, rather it has an escape wheel, with 12 teeth, and an escape pinion, with three. Each has three levels of teeth. The lowest teeth connect the escape wheel and pinion, the next impulse the balance directly, and the topmost interact with the sprung locking detent.

The latest natural escapement from the modern Breguet company, which I covered when discussing the upcoming sympathique does all of this on one level, thanks to modern design and manufacturing technologies.

The tourbillon cage must be poised as well, note the two sections of removed material to balance the assembly. Image – Sotheby’s

Breguet equipped his four-minute tourbillons with a free-sprung temperature compensation balance and an overcoil balance spring. The balance beats at 3 hz, which is remarkable considering even 2.5 hz was a high beat rate for the time.

The balance has three arms, which are brass on the outside and steel within. The mismatch in coefficient of thermal expansion between the who materials causes the arms to flex inwards as temperature increases (speeding the watch up) outward at low temperatures (slowing it down), which compensates for the effect of temperature on the balance spring.

Interestingly, the tourbillon assembly is modular, able to be pulled from the movement by removing two screws. Today, H. Moser & Cie uses this approach to streamline servicing. Oddly, the carriage appears unjeweled. In fact, they are but the usual arrangement is reversed, with the jewel bearings on the tourbillon cage and the pivots on the bridges.

The tourbillon module extracted from the movement. Image – Sotheby’s

Despite its obvious significance, this pocket watch arguably isn’t a “hot” watch in the current market. However, there are probably two or three collectors out there who will bring it well past the seven figure mark. Ownership of a watch like this comes with the responsibility of preserving an important milestone in humanity’s pursuit of mastery over time, a heavy burden.

Breguet no. 1890 has an estimate of CHF350,000-600,000 (US$430,000-960,000). For more, visit Sothebys.com.

Back to top.