Explained: Dial Making at A. Lange & Söhne

The cadraniers of Glashütte.

Since its rebirth in 1994, A. Lange & Söhne has built an enviable reputation among collectors, based in large part on its rich portfolio of movements. Visiting the manufacture in Glashütte, it’s easy to see why; nearly all of the roughly 650 staff are engaged in some aspect of movement production. As a result, in little more than 30 years, Lange has commercialised 75 distinct calibers and has the manpower to apply a consistent level of finishing across the entire range, from the simple to the sublime.

Historically, this single-minded focus on movements has meant that dials have often taken a back seat. Though uniformly high quality and made of noble materials like sterling silver and solid 18k gold, the brand’s dials tend to be simple, classical, and austere. An obvious exception that springs to mind is the sapphire crystal-dialed Lumen series, but sapphire crystal is a common material in watchmaking and these dials tend to be produced in a relatively industrial manner.

Despite its focus on movements, Lange began to stretch its wings with artisanal dials as far back as the year 2000, first with enamel and later with mother-of-pearl, guilloché, tremblage, free-hand engraving, aventurine glass, and onyx. Most of these dials were produced by suppliers, but the brand has quietly built an immensely talented team of engravers and enamellists since launching the Handwerkskunst editions in 2011, and now crafts some of the industry’s most extraordinary dials within its own four walls.

Champlevé enamel

To get a feel what what Lange is capable of, one need look no further than the recently launched 1815 Tourbillon Black Enamel, a limited edition of 50 watches with the dials all made in house.

Unassuming at first glance, the glossy piano-black dial is produced using the champlevé technique. The term translates roughly as ‘raised field’ and means the dial markings, like the logo and large Arabic numerals, are not printed on the surface of the enamel, but are instead raised up from dial base to sit flush with the enamel surface.

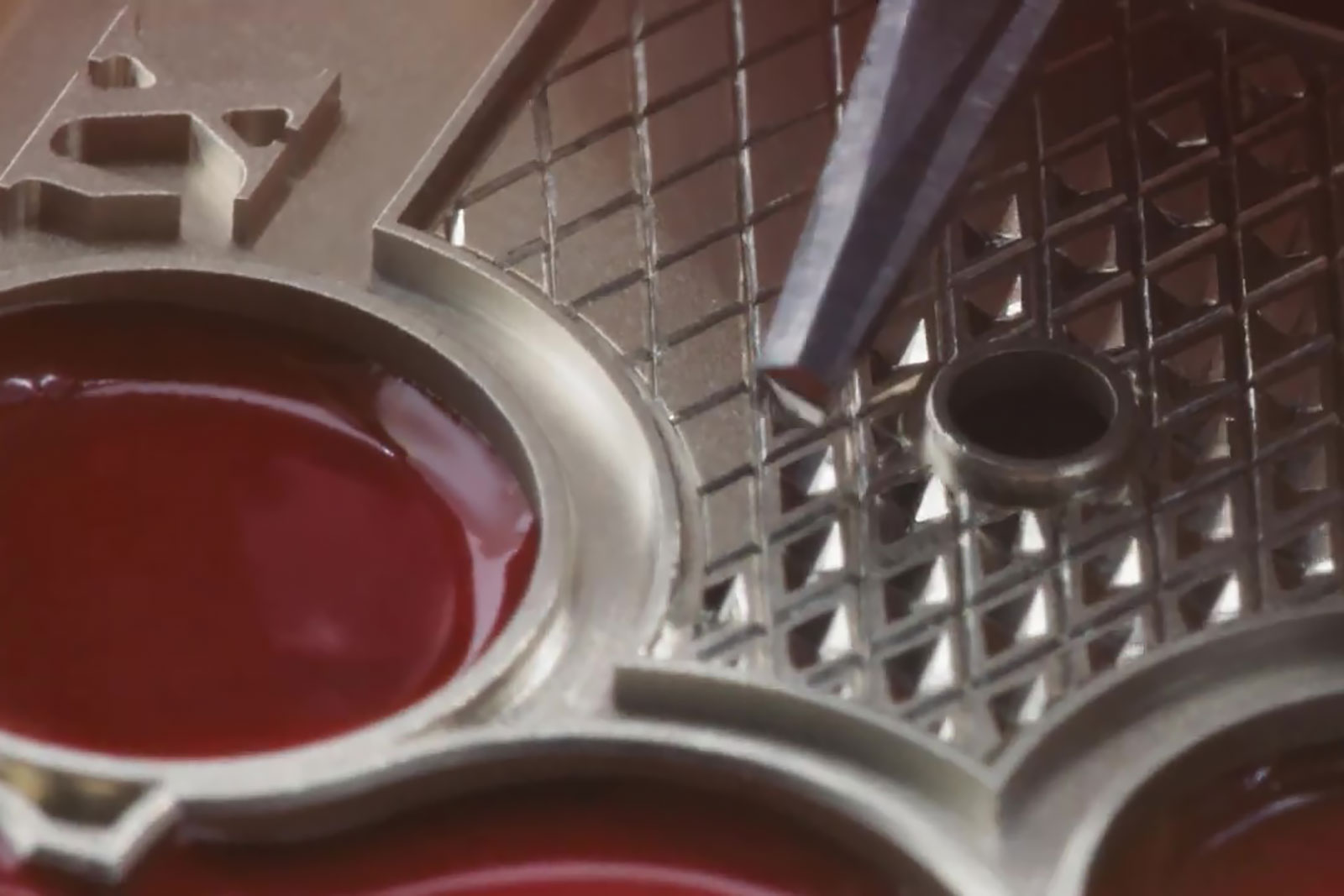

When done well, and the dial of the 1815 is done very well, the effect is almost magical. In the case of the 1815, the dial begins life as a solid disc of 18k white gold, which is precisely milled to create the logo, numerals, and minute and seconds tracks in relief. An enamellist then grinds enamel frit into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. The powder is mixed with distilled water and painted into the recesses of the dial by hand.

Painting the enamel by hand. Image – A. Lange & Söhne

When exposed to heat, the water evaporates leaving a thin layer of enamel frit on the dial surface. Repeated firings cause the enamel to melt, filling the milled cavities in the dial base.

Firing to set the enamel. Image – A. Lange & Söhne

Note that at this stage of production, the hole for the tourbillon has not yet been drilled, and even this section of the dial is enameled to equalise the pressure across the dial and prevent deformation during repeated firings in the oven.

The mirror-flat dial after polishing. Image – A. Lange & Söhne

The dial is then polished by hand against a grinding wheel, using progressively finer polishing wheels, as observed at Émailleurs de la Cité. The polishing stages are critical for achieving a perfectly flat surface. Polishing is especially crucial when it comes to champlevé, and is the secret to getting the surface of the dial perfectly flush with the raised dial markings.

The resulting look is ethereal. Since the lettering is raised from underneath, there’s no paint bleed; the edges of all of the dial markings are perfectly crisp and will remain so permanently. Due to the dial’s extreme flatness, the play of light is extraordinary, with the polished gold markings completely disappearing into the inky black surface at some angles, while practically glowing at others.

The Lange 1 Tourbillon Handwerkskunst

The new 1815 Tourbillon Black Enamel is not the brand’s first foray into champlevé in its in-house dial workshop. That honour goes to the Lange 1 Tourbillon Handwerkskunst edition from 2014, arguably the most desirable Lange 1 reference yet made. Like its sibling, the dial of the Lange 1 Tourbillon Handwerkskunst is enamelled across its entire surface before the hole is cut for the tourbillon and its black polished bridge.

Given the effort Lange has taken to develop this competency in-house, I’m hopeful we’ll see more of this in the years to come.

Traditional grand feu enamel

Lange’s experience with enamel isn’t confined to champlevé, and extends to traditional grand feu enamel dials as well. The first was the Langematik Anniversary introduced in 2000, which was followed by the Richard Lange Pour le Merite in 2009.

At this stage in its development, the brand was reliant on suppliers for these dials, which exhibit a degree of variability from one to the next. For this reason Langepedia sagely recommends examining any specific example prior to purchase. I’ve also observed at least one Richard Lange Pour le Merite dial that exhibited an orange peel-like texture when viewed at an angle; a sign of incomplete polishing.

The Langematik Anniversary was the brand’s first watch with an enamel dial. Image – Langepedia

But since bringing this skill set in-house, the quality appears to have improved and become more uniform. A good outcome like this is by no means certain; specialists exist for a reason and often have experience that’s difficult to replicate. That Lange has pulled it off is a testament to the dexterity of its artisans and what must be a thorough training programme.

The three-piece enamel dial of the Richard Lange Minute Repeater.

Lange often applies different skillsets within a single dial, and even when producing a traditional enamel dial with printed markings the brand sometimes can’t help but go a little further.

In the case of the Minute Repeater Perpetual Calendar, the black enamel dial features four separate white gold rings set into the dial to help define the chapter ring and each of the three sub-dials. But unlike the flush-fit champlevé numerals of the 1815 Tourbillon Black Enamel, the Roman hour markers on the Minute Repeater Perpetual are applied to the dial surface.

Natural stone dials

Stone dials have become something of a trend over the past couple of years, up and down the price spectrum. Evidently this trend reached eastern Germany earlier this year when the brand launched the 30th Anniversary edition of the Lange 1 featuring a glossy black onyx stone dial.

Though used once before about two decades ago, stone dials represent new territory for Lange. Naturally, the brand approached its recent development with characteristic attention to detail, affixing a thin wafer of onyx to a solid silver dial base to enhance longevity. Onyx is surprisingly similar to black fired enamel visually, but while the enamel dials are now made in house, Lange taps specialist suppliers for its stone dials.

The Lange 1 30th Anniversary Limited Edition features a wafer-thin disc of natural black onyx affixed to a sterling silver dial base. Image – A. Lange & Söhne

While stone dials feel increasingly common across the industry, most makers seem to be sticking with eye-catching minerals like malachite, turquoise, and tiger iron. In contrast, Lange’s choice of black onyx, which could easily pass for enamel, suits the brand’s austere aesthetic.

I expect we’ll see more onyx dials in the future, but the brand has shown enough restraint with its unusual dials in the past that I doubt we’ll see it often enough for it to lose its novelty.

The glossy black onyx dial of the Lange 1 30th Anniversary Limited Edition could almost pass for black enamel. Image – A. Lange & Söhne

Tremblage

Tremblage is a type of engraving that involves thousands of mostly random scratches created free-hand using a sharp handheld tool called a burin. When done well, it results in a uniform frosted surface designed to contrast with raised, polished borders and dial markers.

Lange deserves credit for popularising the use of tremblage in contemporary watchmaking. While quite popular today, the technique was almost unheard of when the brand launched the Richard Lange Tourbillon Pour le Mérite Handwerkskunst in 2011. Since then Lange has used the technique sparingly, only on pieces within the Handwerkskunst series.

The extraordinary dial of the Zeitwerk Handwerkskunst.

At first glance, the tremblage dial of the 1815 Tourbillon Handwerkskunst is remarkably similar to the machined dial base of the 1815 Tourbillon Black Enamel examined above.

The 18k pink gold dial base begins life in much the same way, and manages to be both simpler and more labour-intensive than its glossy black counterpart. The railroad tracks around the main chapter ring and tourbillon cage are pad printed, but the recessed surfaces are given a matte finish through several thousand short cuts of the burin, giving it an indestructible, almost medallion-like look and feel.

Whether tremblage looks good or bad depends in large part on the size of the indentations and their uniformity. The best dials require a close look to see any individual marks, and appear evenly frosted at a distance.

Free-hand engraving

Free-hand engraving is another strength of Lange, which is famous for its hand-engraved balance cocks. But the brand’s in-house engravers havealso used this technique dial side on select Handwerkskunst pieces including the Cabaret Tourbillon and Lange 1 Tourbillon Perpetual Calendar.

The free-hand engraved dial of the Cabaret Tourbillon Handwerkskunst. Image – A. Lange & Söhne

The dial of the former appears far too uniform to be the result of handwork, but close examination reveals indelible traces of the human hand. Straight lines and geometric patterns are dangerous in watchmaking because they tend to reveal imperfections more easily than more organic designs. This is why Clous de Paris, among the simplest of all guilloché patterns, is one of the most challenging to execute perfectly since the slightest misstep will stand out vividly.

Free-hand engraving the geometric pattern on the dial of the Cabaret Tourbillon Handwerkskunst. Image – A. Lange & Söhne

This is what makes the dial of the Cabaret Tourbillon Handwerkskunst so impressive; the center of the dial is decorated with a geometric diamond pattern cut entirely free-hand. As discussed previously, Lange likes to mix decorative techniques so when the engraver was finished the pattern was further embellished with a layer of clear enamel, on which the logo was pad-printed. The process of applying transparent enamel over an engraved surface is known as flinqué.

The flinqué enamel layer on the dial of the Cabaret Tourbillon Handwerkskunst. Image – A. Lange & Söhne

Another Handwerkskunst edition that blends enamelling with engraving is the 1815 Rattrapante Perpetual Calendar, which gets the full champlevé treatment on both its dial and hinged case back.

The latter features a show-stopping engraving of Luna, the Roman goddess of the moon, while the surrounding night sky is rendered in translucent blue enamel to match the dial.

The mixed methods continue on the Lange 1 Tourbillon Perpetual Calendar, which features free-hand engraved florals against a tremblage background. With a combination of methods like this, there’s one simple rule: don’t slip up. I can only imagine the engraver’s sigh of relief when the final stroke has been made.

Aventurine glass

A few years ago Lange got bitten by the bug for aventurine glass dials, which were already becoming somewhat common. Aventurine glass, which the brand terms ‘gold flux,’ is a man-made material that first emerged in Venice about 400 years ago. It is produced by adding metal oxides to molten glass; as the mixture cools, the oxides crystallise into reflective particles that create the material’s characteristic sparkle.

The Saxonia Thin was the brand’s first model to feature a dial made from aventurine glass. Image – A. Lange & Söhne

The brand debuted this material on the Saxonia Thin, before later expanding it to the Little Lange 1. The material suits Lange’s refined, formal aesthetic; it’s subtle at a distance but reveals a shimmering personality up close.

Mother-of-pearl

Though Lange does not have any mother-of-pearl dials in its current line-up, the brand has used this material, with and without guilloché, to give certain limited edition models a distinct personality over the years. Though naturally occurring, mother-of-pearl, also known as nacre, is not a mineral stone like onyx, and is instead produced by certain mollusks inside their shells by the same organic processes that produce pearls. Due to its natural translucency and iridescence, mother-of-pearl has been prized as decorative element in jewelry for thousands of years.

The Grand Lange One Limited Edition for Dubail, ref. 117.040. Image – Phillips

As a dial material, mother-of-pearl is appealing for several reasons. Chief among them is the fact that since the material is organic, no two dials are exactly alike. Each dial will have a different degree of translucency and the naturally occurring patterns, which often resemble clouds, will also vary from dial to dial even within the same series.

Mother-of-pearl wafers can also be set atop coloured plates, changing their characteristics and enabling dial makers to bring out specific textures present in the material to suit the theme of a particular watch. Even aside from variations in the nacre material itself, this helps explain the numerous colours on offer across the industry.

Though mother-of-pearl is most commonly used for women’s watches, I find the material quite appealing and would not hesistate to wear one personally if the overall colour and design were to my liking.

Guilloché

Historically, engine-turning never really caught on in Germany in the same way that it did in France, England, and Switzerland, but Lange has employed the technique selectively over the years to good effect. The most significant example is probably the Lange 1A from 1998, but the technique has also been applied to other models, including some with mother-of-pearl dials.

Lange makes no secret of the fact that its guilloché dials are engraved using CNC rather than a hand-operated rose engine. This takes away some of the romance, but the outcome is nearly indistinguishable.

Guilloché by CNC is a happy medium between engine turning and stamping, since the former is extremely labour-intensive and the latter loses the crisp edges of the real thing. CNC milling also opens up new possibilities for patterns that would be especially difficult or even impossible with a traditional rose or straight-line engine.

The guilloché pattern similar to that used for the Lange 1A has also been featured on the mother-of-pearl Lange 1 Soirée ref. 110.030 and a few Little Lange 1 references as well. It’s a fussy, baroque affair that is somewhat at odds with the typically austere Lange look.

To my eye, guilloché somehow feels more Lange-like with a simpler pattern, like that used for the 165th Anniversary Homage set from 2011, which confines the engraved pattern to just the central portion of the time display.

Concluding thoughts

For a brand known primarily for its movements, Lange has produced a diverse range of exceptional dials in a short period of time. While some are produced with the help of elite suppliers, a growing number are fabricated in-house. Looking at the brand’s history, a couple of themes emerge.

First, Lange is disciplined. With exceptions so rare they prove the rule, the brand has reserved hand-engraved dials for its Handwerkskunst series and has used materials like onyx, mother-of-pearl, and enamel selectively for limited editions. This discipline helps the brand stay focused on movements and prevents fatigue among its customers.

The second theme is the remarkable quality of these dials. Though the brand experienced some irregularity in the enamel dials it sourced externally in its early years, it learned that if you need something done right, sometimes you have to do it yourself, and later developed the in-house skill to do so.

Back to top.