Inside Akrivia’s Enamel Workshop in Geneva

Visiting Émailleurs de la Cité.

The world of Swiss watchmaking is a small one; everyone seems to know everyone. This is especially true among the exclusive ranks of enamellers. In total, there are about 120 practicing enamellers in Switzerland, largely concentrated in Geneva, which has been a leading hub for fine enamelling for more the 400 years.

Of these, four artisans have recently taken up residence at Émailleurs de la Cité (EC) in Geneva’s Old Town. A newly established enamel workshop founded by Rexhep Rexhepi of Akrivia and Florent Olivier Martin, EC crafts a small number of grand feu enamel dials annually for Mr Rexhepi’s own watches and for select clients like Biver.

Though recently opened, the workshop has the feel of a mature and highly organised operation, benefiting from the obvious experience of the staff – Mr Martin was formerly the production director at the respected dial specialist Olivier Vaucher – and the attention to detail for which Mr Rexhepi is known.

The enamel workshop is a fitting addition to his growing empire, and is conveniently located just steps away from Akrivia’s watchmaking atelier on Grand-Rue, the picturesque cobblestone thoroughfare that runs through the Old Town.

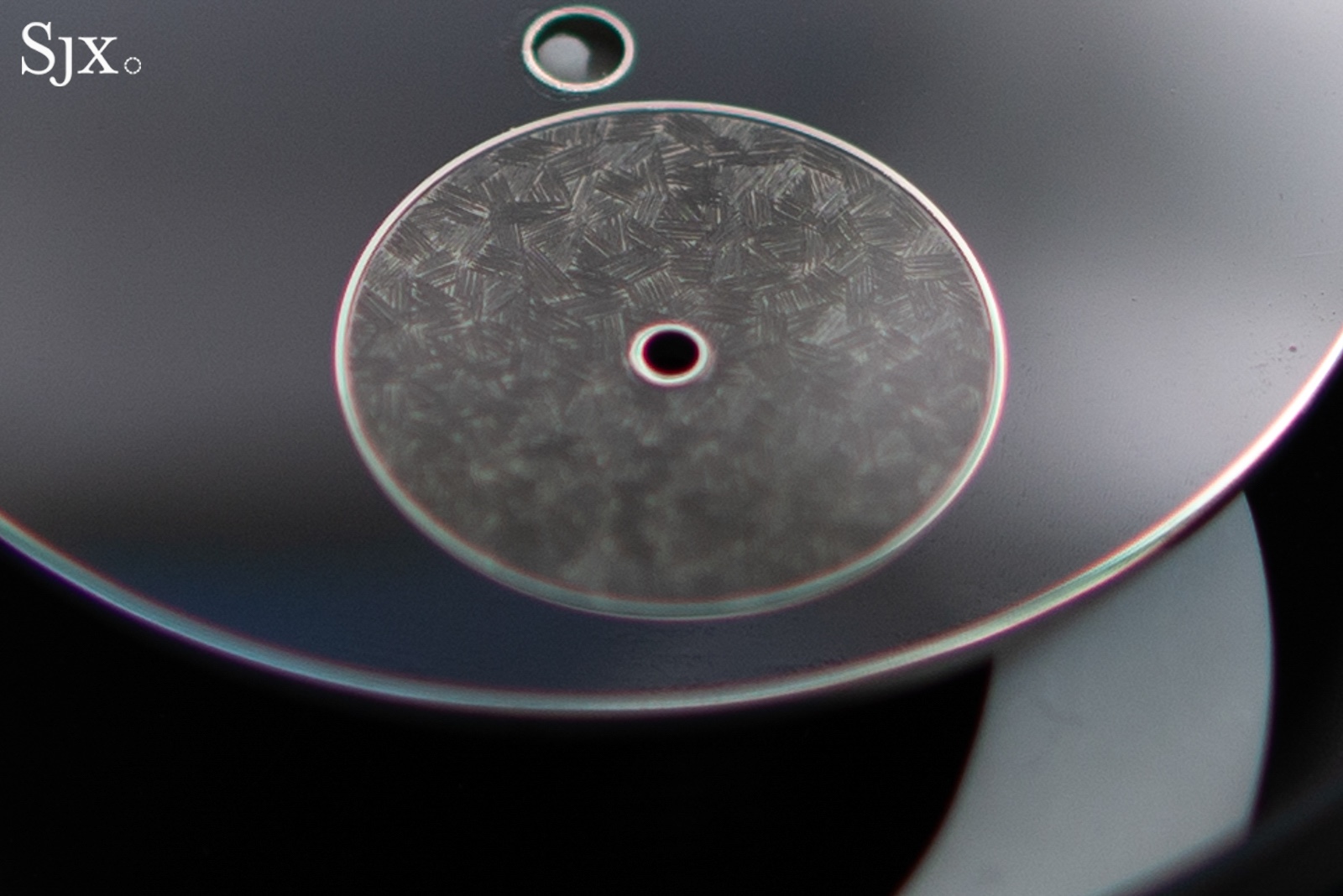

The hand-engraved gratté pattern is applied personally by Mr Rexhepi.

The art of enamel

Brands like Patek Philippe consider enamel a “rare handcraft”, and for good reason. While industrial groups like the Swatch Group seem to have largely mastered the production of quality enamel dials at (vast) scale, the very best dials still require the dexterity of an artist, the patience of a saint, the mind of a winemaker, and the tools of a dental clinic – more on this later.

Due to the complex, sensitive nature of the material, enamel dials are known to have a very high rejection rate; even with painstaking preparation and meticulous effort, many dials develop flaws during production that render them worthless. The cost of this wastage is rolled into the price of finished dials, which can push the value of a single dial into the low five-figure range.

It’s an almost organic process, and there are a lot of things that can go wrong. For example, if the enamel frit (essentially powdered glass and pigments) is not perfectly clean, the impurities can burn and stain the dial. Similarly, tiny air bubbles can act like ticking time bombs, popping when heated, creating pockmarks that can’t be polished out. Even fluctuations in the humidity and temperature in the workshop can change the behavior of the enamel.

But the finished dials that emerge successfully often possess a degree of ethereal perfection and permanence that makes the costly effort worthwhile.

A completed dial for the Rexhep Rexhepi Chronomètre Contemporain II Diamant

The initial stages: Grinding and preparation

The enameller starts by choosing a colour of enamel frit from a vast assortment kept in inventory. This sounds like it should be the easiest part of the process, but colour selection is actually quite nuanced since the colours often change when they are fired, with the final shade being determined by the specific firing temperature.

This requires the enameller to have a sommelier-like understanding of the behavior of different pigments at different temperatures, in order to be able to select the right coloured frit for the desired outcome.

Once the colour is chosen, the frit is ground manually with a mortar and pestle. Distilled water is used to wash the frit at different stages to remove any impurities that may be present. The grinding and washing process is repeated until the desired grain size is achieved; only the smallest, most even particles are used to ensure uniform behavior during heating and cooling.

Washing the enamel frit

The enamel is then carefully painted onto the surface of a grey gold dial base. Grey gold is an alloy of gold and palladium, prized by enamellers because remains stable even after repeated firings. To help the enamel adhere evenly, the dial blanks are left with an intentionally coarse unpolished surface.

Firing

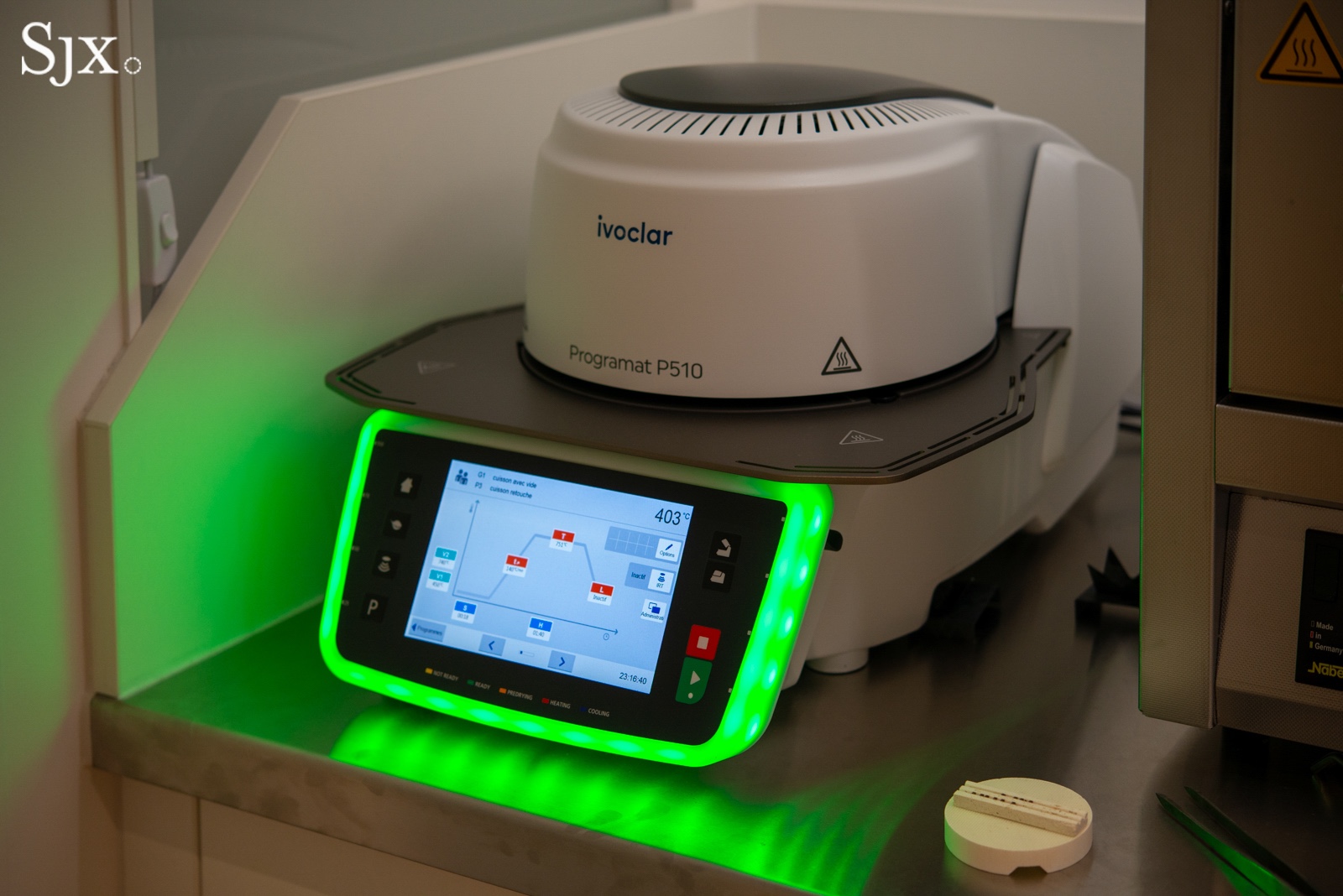

Things start heating up when the dials are transferred to the firing station. The firing process begins by placing the dial in a dental-grade vacuum furnace, akin to a small oven that sucks out all the air while maintaining a precisely controllable temperature. This type of machine is more commonly used by dental technicians to create ceramic crowns, but it works just as well for enamel dials.

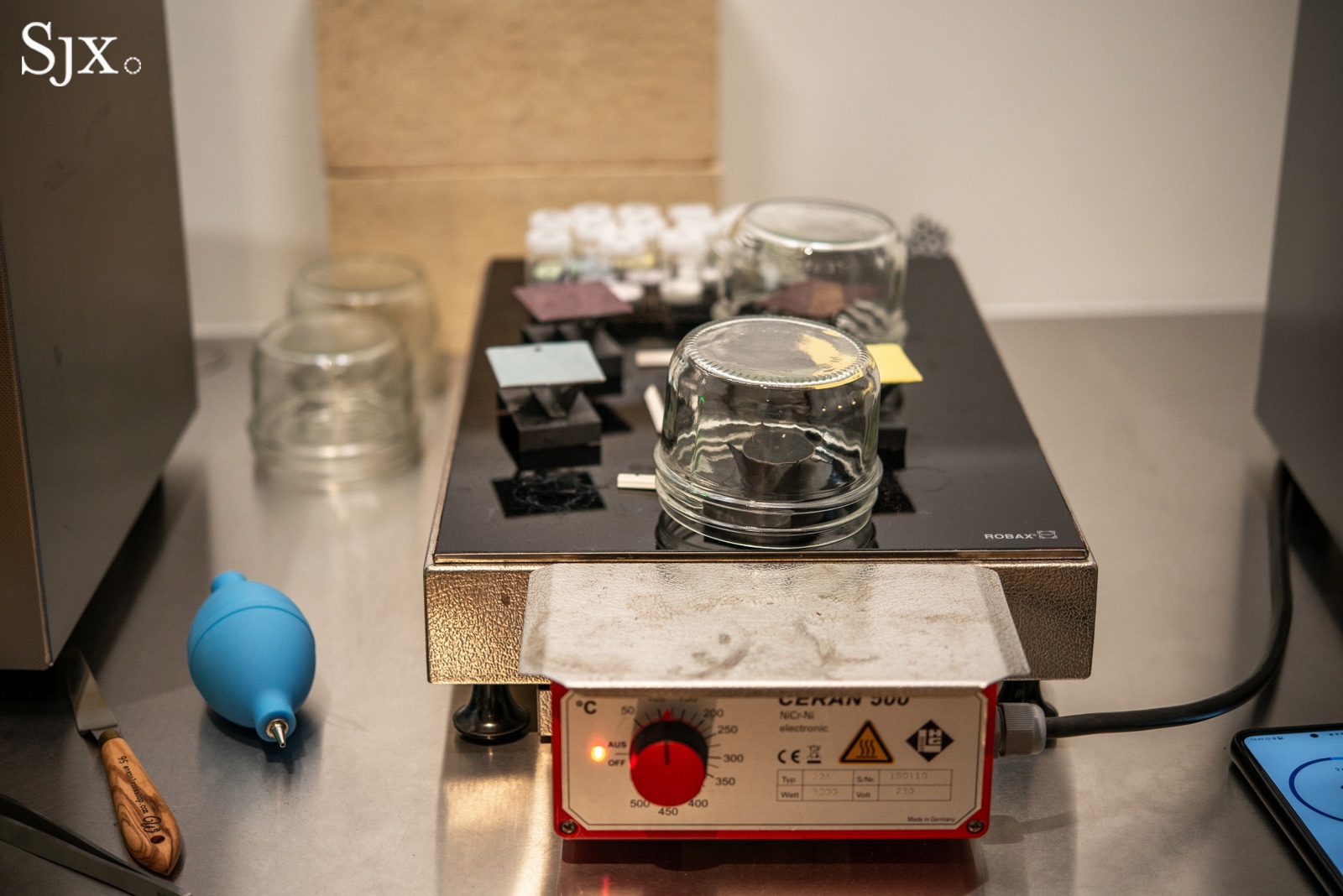

From left, the vacuum furnace, oven, and heating plate

By applying heat under vacuum, this device helps eliminate air bubbles prior to firing. In dental work, an air bubble can cause a crown to crack; in dial-making air bubbles can pop leaving behind unsightly divots in the dial surface.

The vacuum furnace in action

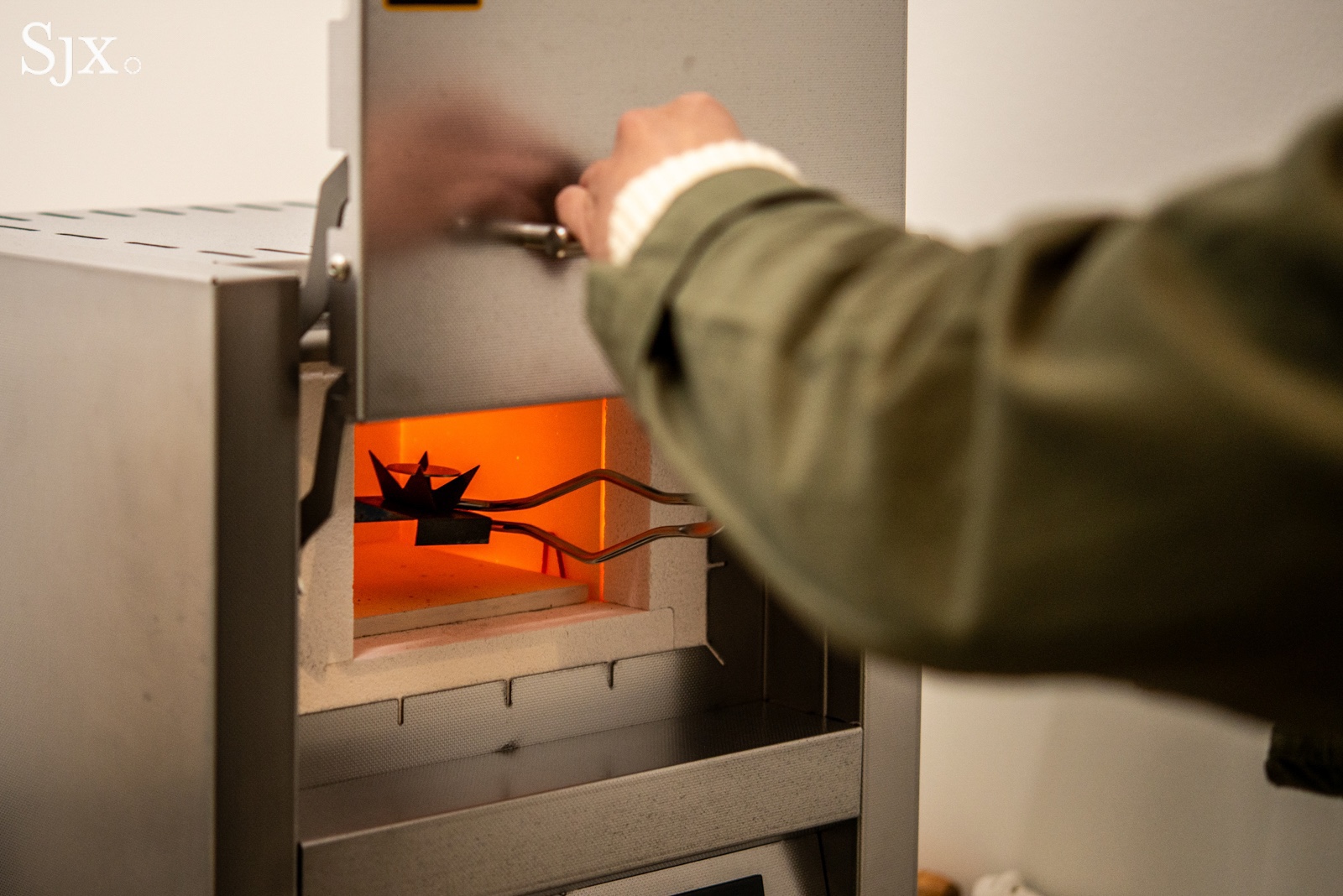

After a stint in the vacuum furnace, the dial takes a break on a dehumidifier plate. Once the desired resting temperature is reached, the dial goes into the oven, supported by a special holder designed to facilitate even heating.

The dehumidifier plate

An enamel dial going into the oven

Since enamel and grey gold have different coefficients of thermal expansion, the dials can warp when exposed to significant temperature fluctuations, causing the enamel to crack.

For this reason, all high-end dials, like those made at EC, are counter-enamelled, meaning the back of the dial is also enamelled. The counter-enamel functions like the stays on a suspension bridge, providing a counter-balancing force to keep the dial flat.

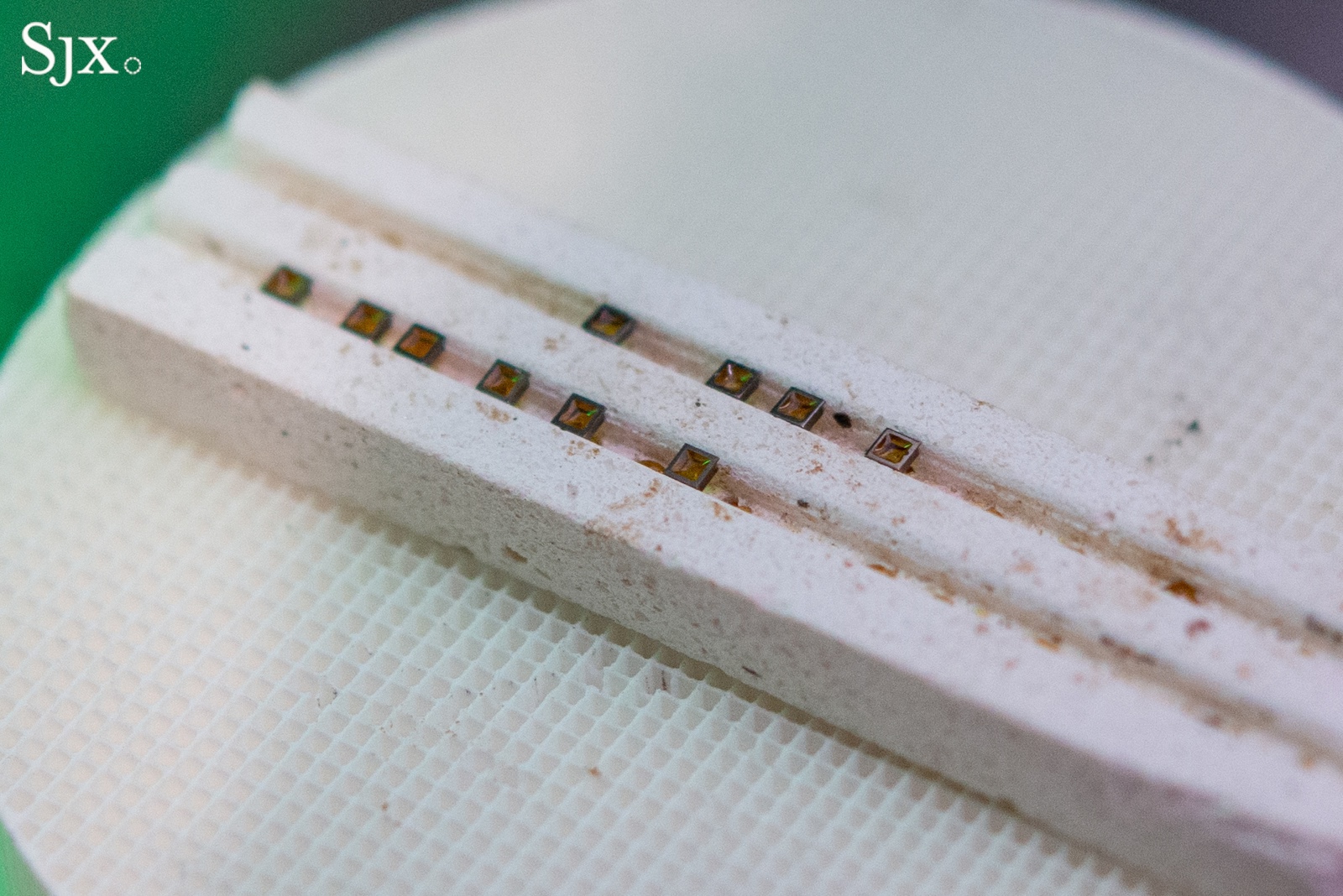

Hour markers for the Louis Vuitton x Rexhep Rexhepi LVRR-01 Chronographe à Sonnerie feature translucent enamel; here several are shown cooling

Polishing

After a dial has been fired and found to be within spec, the polishing stages begin. The dials are ground against progressively finer polishing wheels, following the same steps used to achieve the perfect optical-grade finish of eyeglass lenses. This methodical step-by-step polishing process eliminates the dimpled orange peel-like texture that is often seen on lesser enamel dials.

This is a very manual step that requires the artisan to be able to maintain even pressure and ‘feel’ when the dial is ready to proceed.

A look at what the dial looks like between polishing stages

The polishing stages are absolutely critical to achieving the flawless mirror-like perfection that makes the best enamel dials stand out.

A few days after visiting EC, I had the chance to discuss this exact topic over a quick breakfast with Jean-Claude Biver, who selected EC to make the dials for the Biver Automatique Japan Edition. Mr Biver lauded EC for making some of the best enamel dials he’s seen in his 50-odd years in watchmaking.

Tampography

Tampography is the process of printing the dial with a gelatinous transfer pad. A routine practice throughout the industry, we’ve seen this process before at other dial makers like F.P. Journe’s Les Cadraniers de Genève.

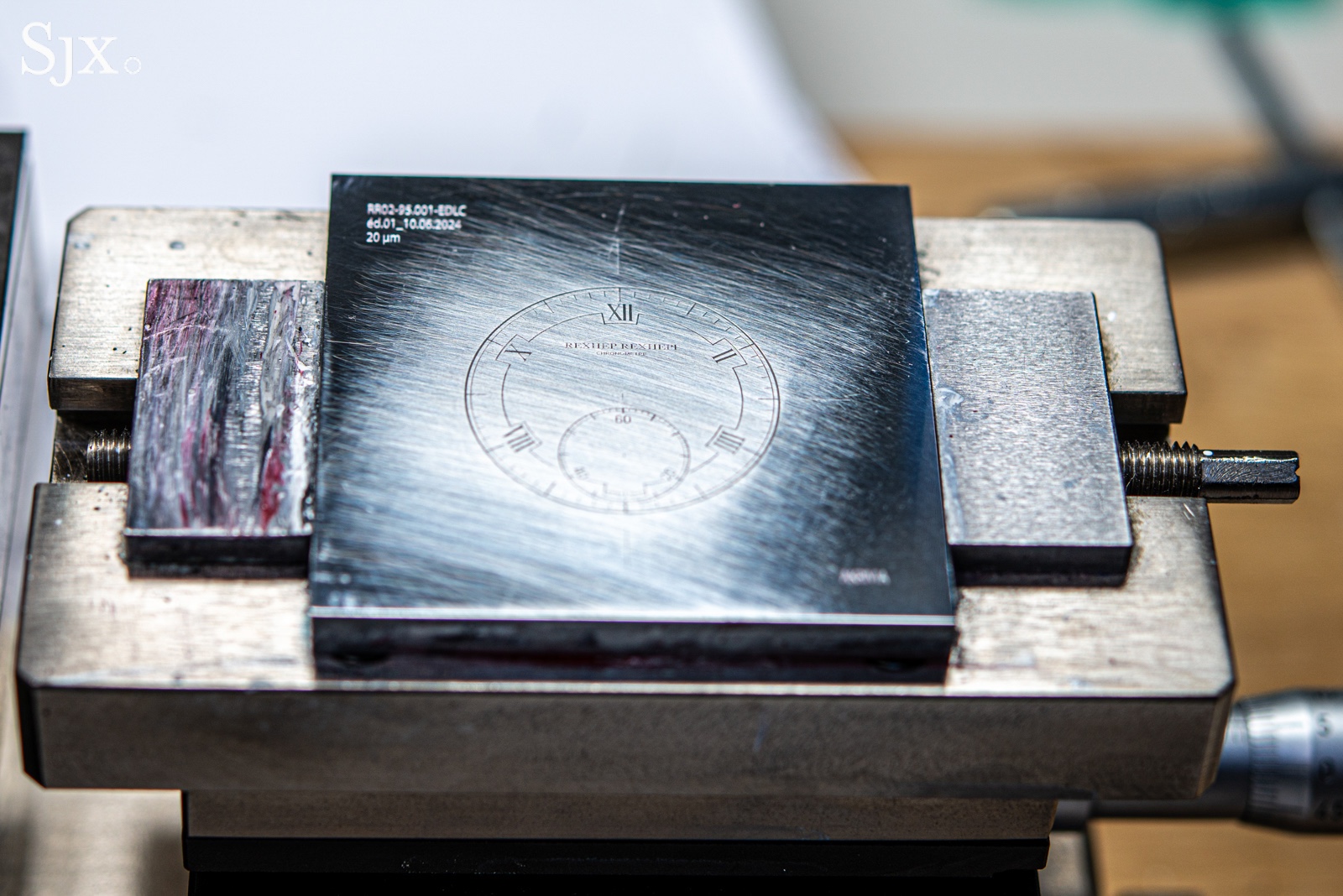

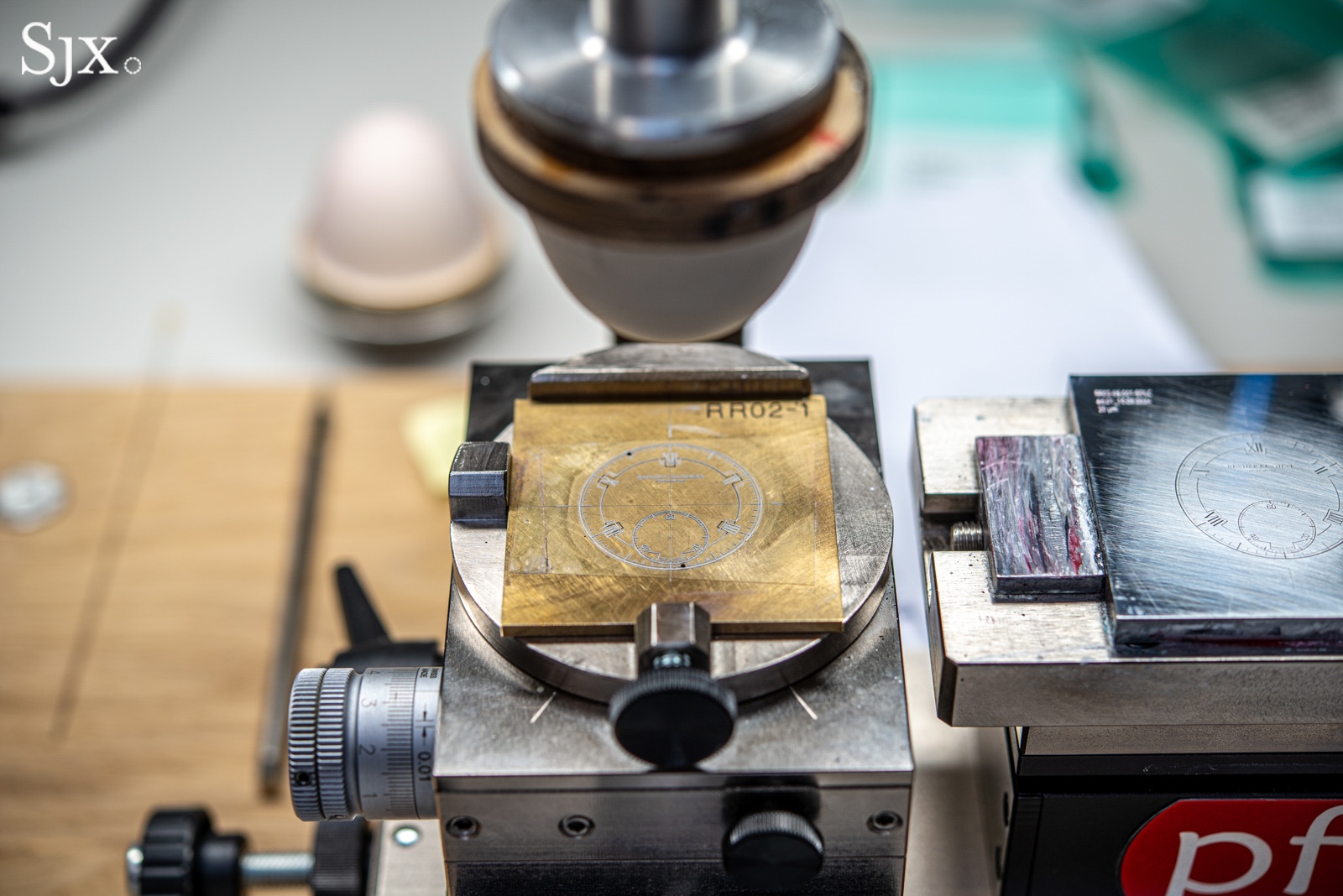

In short, the paint used on the dial is applied to a plate engraved with the master copy of the dial, which is then wiped clean with a blade, removing all the paint except what is left in the engraved markings. The egg-shaped transfer pad is then pressed down until it flattens out, picking up a painted image of the dial.

The ‘master copy’ of the dial

The plate then slides away, bringing the real dial into place underneath the transfer pad, which is then brought down swiftly, printing one layer on the dial. The process is usually repeated multiple times to achieve the glossy, domed markings that most collectors expect.

For the black enamel dial of the Chronomètre Contemporain II in platinum, a type of white acrylic paint is used. On the 18k rose gold model, which features a warm, translucent white enamel dial, enamel paint is used for the markings.

The enamel paint requires an extra layer of fondant, or clear enamel glaze, on top. This finishing touch has its roots in the grand tradition of the Geneva school of enamelling, which first championed the use of clear fondant as a means of protection for elaborate miniature enamel paintings.

While the tampography workshop was being renovated, construction workers discovered something strange. Carved into the foundation, which dates back centuries, a carved face was discovered, which seems to be a charming caricature with long lashes and a bowl cut.

The EC team is still deciding what to name this character, but they’ve already finalised plans to make this the ‘face’ of the workshop in the form of their maker’s mark. In the future, all EC dials will bear this emblem as a hallmark hammered into the back of the grey gold dial base.

The EC maker’s mark

Closing thoughts

Over the years, I’ve seen enough enamel dials with dimpled, uneven surfaces to feel slightly jaded about the whole proposition of enamel. But seeing the process at EC end-to-end opened my eyes to just how much control skilled artisans can exert over this unpredictable medium. Yes, the rejection rate is high, but the perfection of the dials that do make it through feels hard-won.

The enamel’s sensitivity to things like temperature and humidity reminds me of winemaking. Like grapes in a vineyard, enamel is capricious and demanding. Like a vintner, the enameller must anticipate the effect that small actions will have on later stages of the process, and the smallest oversight at any point can ruin an otherwise perfect creation.

Reflecting on the process end-to-end, enamelwork is a fascinating blend of art and science. Though the process for creating modern enamel dials benefits from tools like computer-controlled vacuum furnaces, there is a great deal of artistry found in the enameller’s dexterous touch and intuition for transformation.