Hands-On: Brivet-Naudot Eccentricity

Hand-made and mechanically exotic.

French watchmaker Cyril Brivet-Naudot made his debut two years ago with the Eccentricity, a time-only watch that’s fascinating and impressive on many fronts. Not only is it almost entirely made by hand, the Eccentricity is intriguing in design and mechanics – from the overall architecture to details like the key-winding mechanism and regulator-style time display with a twist, and above all, the proprietary escapement.

Just 29 years old, Mr Brivet-Naudot began working on the Eccentricity after graduating from the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), one of Switzerland’s best technical universities. Prior to that, he earned a diploma in watchmaking from the Lycée Edgar Faure in Morteau, a small town in eastern France that borders Switzerland. The school has gained a reputation for producing imaginative watchmakers, many pursuing a similar style that’s inspired by 19th century pocket watch movements, including Theo Auffret, a peer of Mr Brivet-Naudot.

The result of three years of development, the Eccentricity is very much in the same vein as the watches produced by Mr Brivet-Naudot’s fellow graduates. It artfully combines a 19th century aesthetic sensibility with exotic features, including a novel, free-eccentric escapement, for which the watch was named. And it is built by hand: with the exception of the mainspring, hairspring, jewels and crystals, every component of the watch was made from scratch by Mr Brivet-Naudot, without the aid of CNC machines.

Case and dial

Made entirely by hand, the case is simple in form and execution – essentially a container for the movement. It’s stainless steel and a compact 39 mm across, with brushed flanks and a polished bezel, which contrasts nicely against the gold frosted dial. The simplicity of the case directs attention to the dial and movement, but also reveals the limitations in case making for independent watchmakers.

Though it seems slightly smaller due to the absence of a crown, the case has a distinctive presence as a result of its perfectly round shape that is accentuated by the rounded bezel. The lugs are narrow but tall, and look fairly stiff at a distance, but they are slightly angled for a marginally closer fit on the wrist.

No crown, just key

Even though the case is simple, it reveals Mr Brivet-Naudot’s attention to detail: the case back is secured to the case middle by six hand-made screws with eccentric heads – featuring two circular slots of unequal size – that echo the wheels of the going train visible through the back. The “eccentric” motif of a large and small circle side by side is something that recurs subtly throughout the watch.

The back with its six eccentric-head screws

The dial – which is actually the base plate of the movement – is notably well-executed and visually engaging. Continuing the theme of the watch, time is displayed in a sub-dial with a “eccentric”, regulator-style time display. It is made up of a rotating minute ring that surrounds the hour indicator.

The minute ring is attached to a clear sapphire disc that is mounted on the second wheel, making one revolution every hour, with the current minute indicated by a fixed, blued-steel pointer.

Fixed to the revolving sapphire disc is the tiny hour sub-dial and its even tinier blued-steel hand that relies on a darkened dot to indicate 12 o’clock. Because the hour sub-dial is nestled within the minutes, it also makes one revolution every hour.

But it is important to note the hour sub-dial is not a planetary display; it sits in a fixed position relative to the minute ring, rather than maintaining a vertical alignment throughout its motion. That makes reading the hours a little confusing, especially given the tiny hour sub-dial.

The time above is 12:05

The gold plaque that bears the watchmaker’s name is finished with a brushed surface and polished, bevelled edges – and secured with “eccentric” screws

But the time display is not the only animation on the face – positioned next to it is the massive balance wheel that beats at a slow and attractive pace of 2.5 Hz, creating near-perfect symmetry.

Free-sprung and fitted to an overcoil hairspring, the balance is held in place by a frosted, gilded balance cock that makes it even more striking, and emphasises the absence of the escapement.

Free eccentric escapement

Due to the elaborate construction of the escapement – it comprises a total of 19 components – it is located at the back of the watch. The escapement was developed with the help of Luc Monnet, a watchmaker who spent his career as a builder of prototypes at Greubel Forsey and Audemars Piguet before setting up his own workshop specialising in restoration and of course, prototypes.

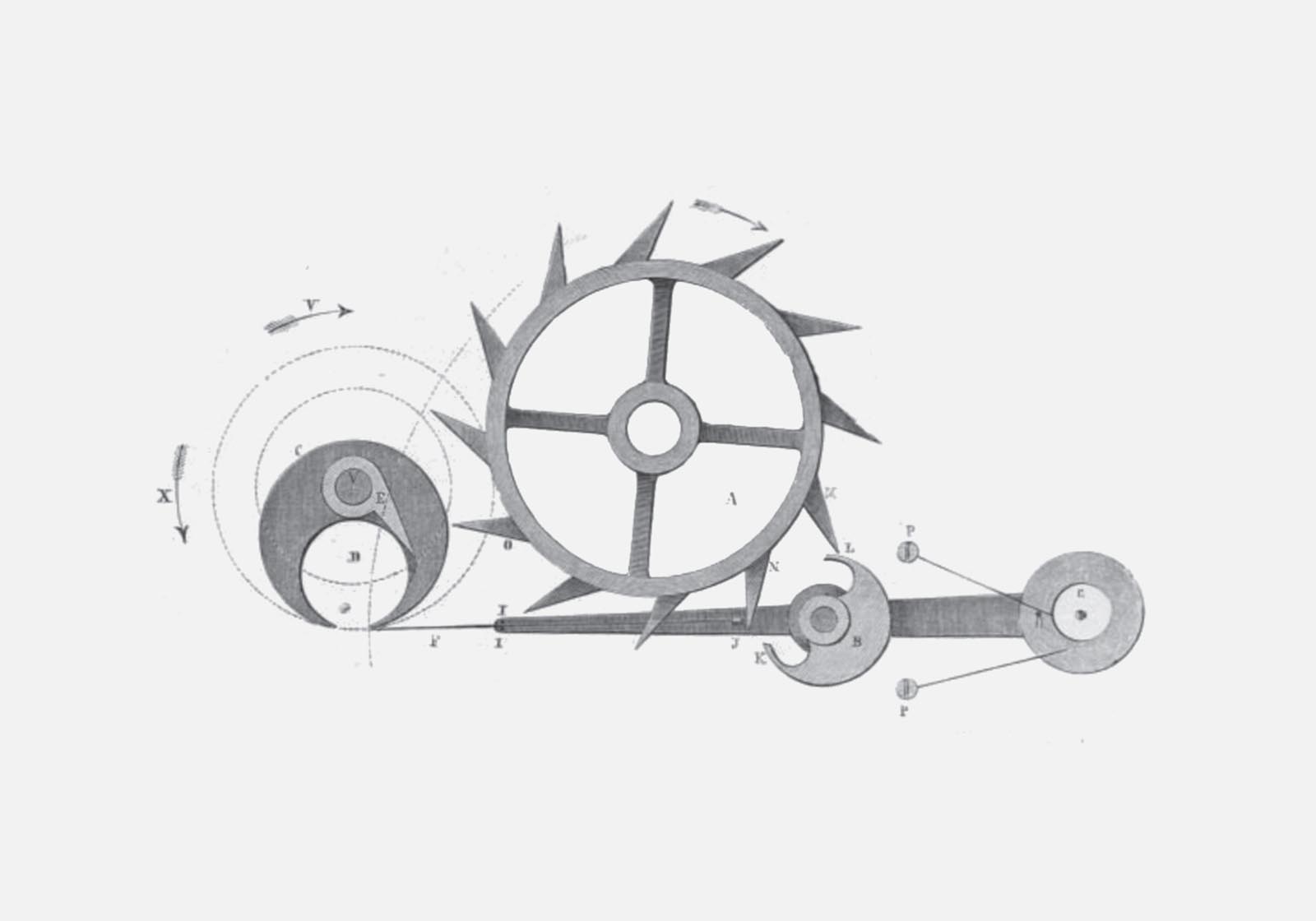

Mr Brivet-Naudot named the invention the free eccentric escapement, or échappement libre excentrique, after the eccentric roller on the balance staff. It is an updated version of the eccentric escapement invented by the great, 19th century chronometer-maker Louis Richard (1812-1875), who was one of the first Swiss producers of marine chronometers on a large scale, along with Ulysse Nardin and Henri Grandjean.

The original escapement invented by Louis Richard. Photo – Brivet-Naudot

Put simply, an escapement regulates the “escaping” of energy from the mainspring. It usually is made up of two key elements: a controlled locking and unlocking system for the escape wheel, which makes the watch tick; and second, a method of providing an impulse to the balance wheel to keep it oscillating.

The ubiquitous Swiss lever escapement does both of this via the pallet fork, a Y-shaped component with pallet jewels in each arm of the “Y”. While it is the de facto standard for mechanical movements worldwide, the Swiss lever escapement is not perfect.

One major drawback of the Swiss lever escapement is that the impulse from escape wheel to balance wheel is indirect – force is not transmitted directly from one to the other, but instead via the pallet fork. And the pallet fork jewels create sliding friction when they forcefully mesh with the teeth of the escape wheel. Also, there is some “draw”, or recoil, in the escapement – the escape wheel springs backward ever so slightly on every beat, due to the unlocking action of the pallet fork.

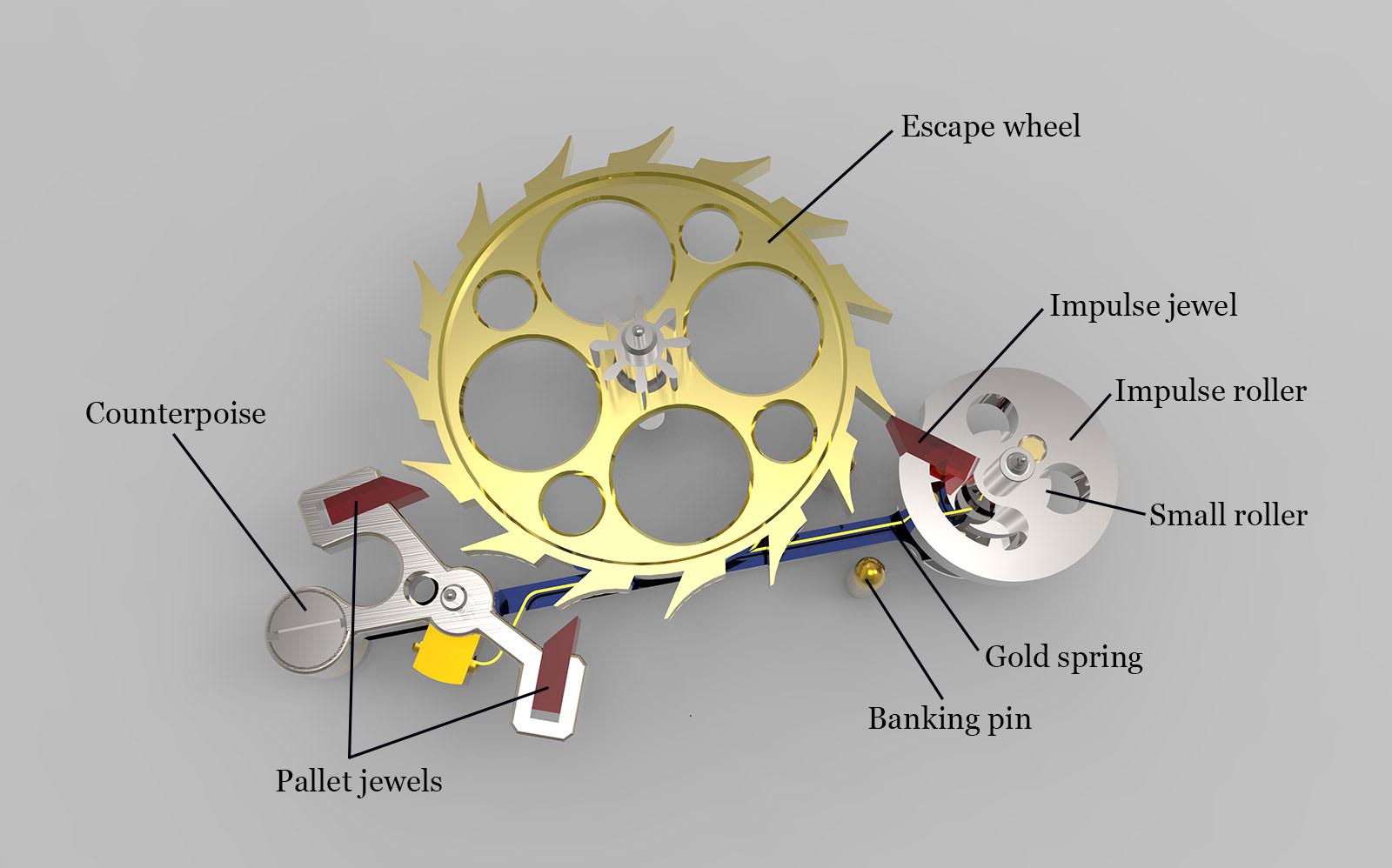

Brivet-Naudot’s escapement, as with other alternatives to the Swiss lever escapement (including the spring-detent, the co-axial, natural, as well as the Robin escapements), is designed to minimise these issues by combining elements of different past constructions. It combines the Swiss lever escapement’s locking and unlocking motion of the escape wheel, with the direct impulse of a detent escapement.

In the free eccentric escapement, the escape wheel tangentially impulses the balance wheel via an impulse pallet, resulting in negligible sliding friction since the contact between the two is tangential. And unlike a Swiss lever escapement that has two impulses per oscillation, this escapement only has one – much like a detent escapement, improving the isochronism of the balance wheel (which refers to a constant period for the oscillation of the balance wheel, regardless of the angle through which it travels – stable timekeeping, in other words).

Diagram – Brivet-Naudot

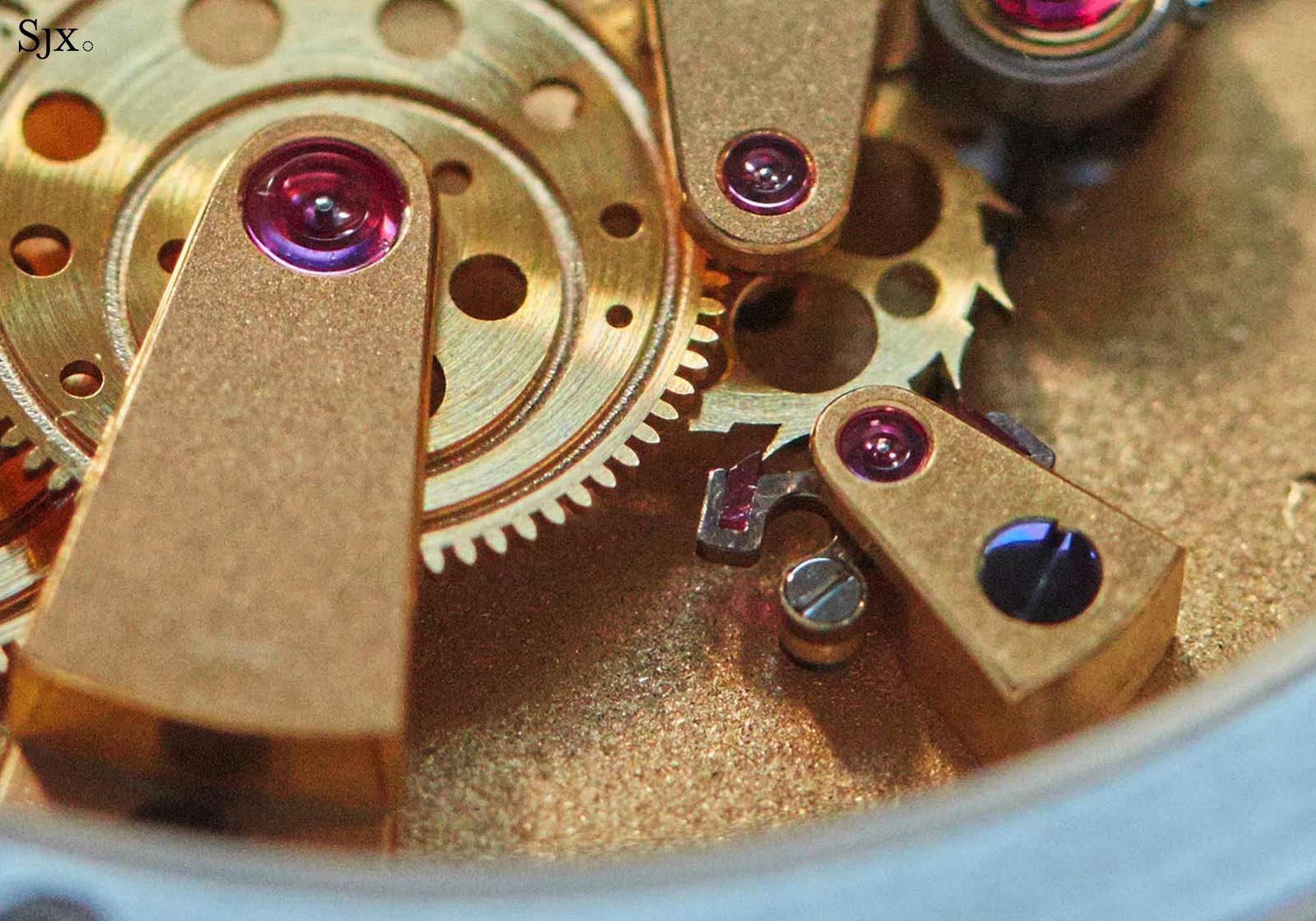

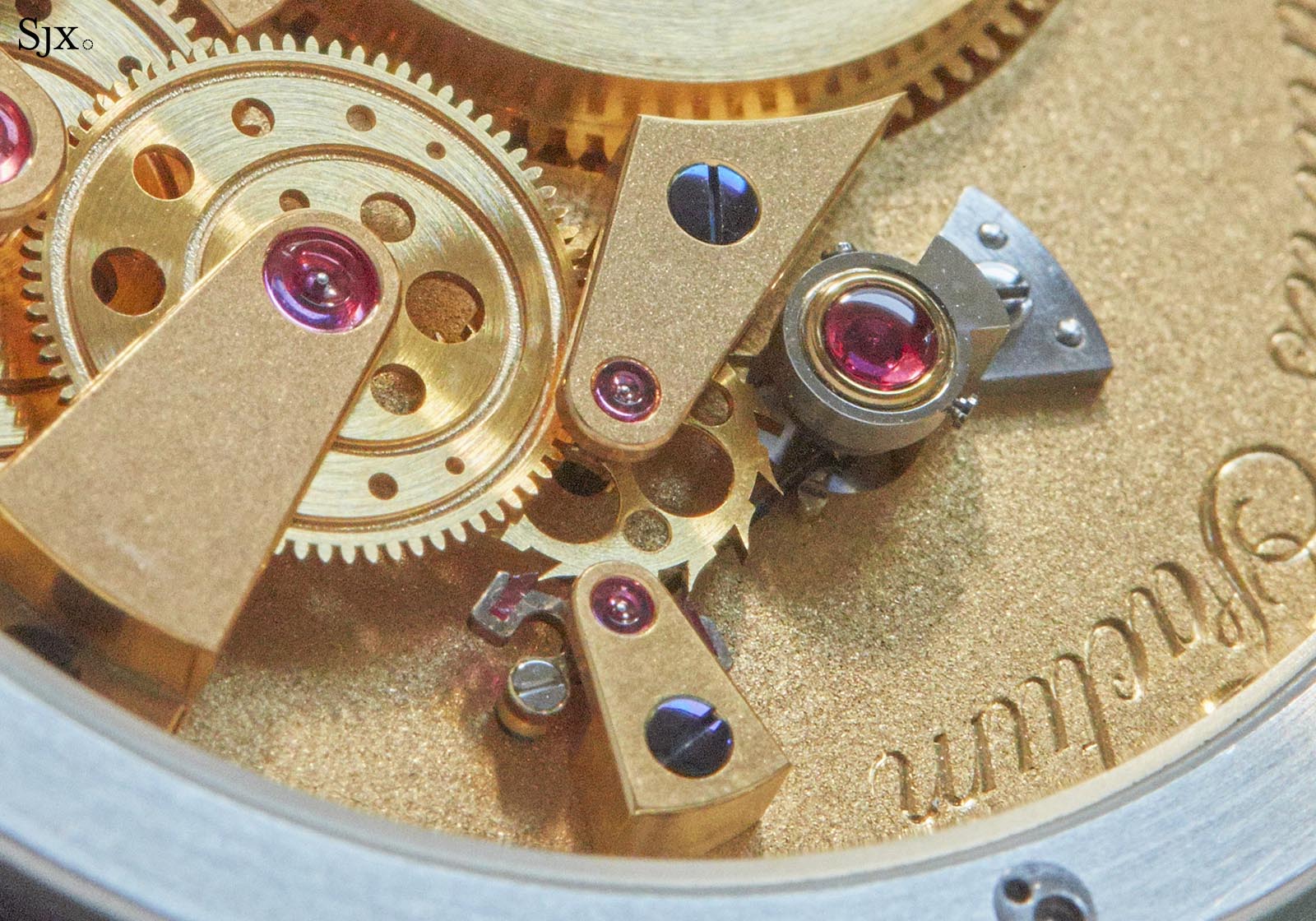

The escape wheel is locked and unlocked by a pallet lever with two pallet jewels, and the pallet lever itself relies on the long gold spring

However, the unlocking of the escape wheel is managed via the familiar pallet lever, with a twist. The pallet lever incorporates a long, stiff gold spring that extends towards the balance wheel, which has a tiny, eccentric roller at its base. With every swing of the balance wheel, the roller pushes against the gold spring, pivoting the pallet lever and causing the escapement to unlock.

If that sounds complicated, it is. As a result, the pallet lever assembly is collectively is made up of an impressive 12 components that form a single part.

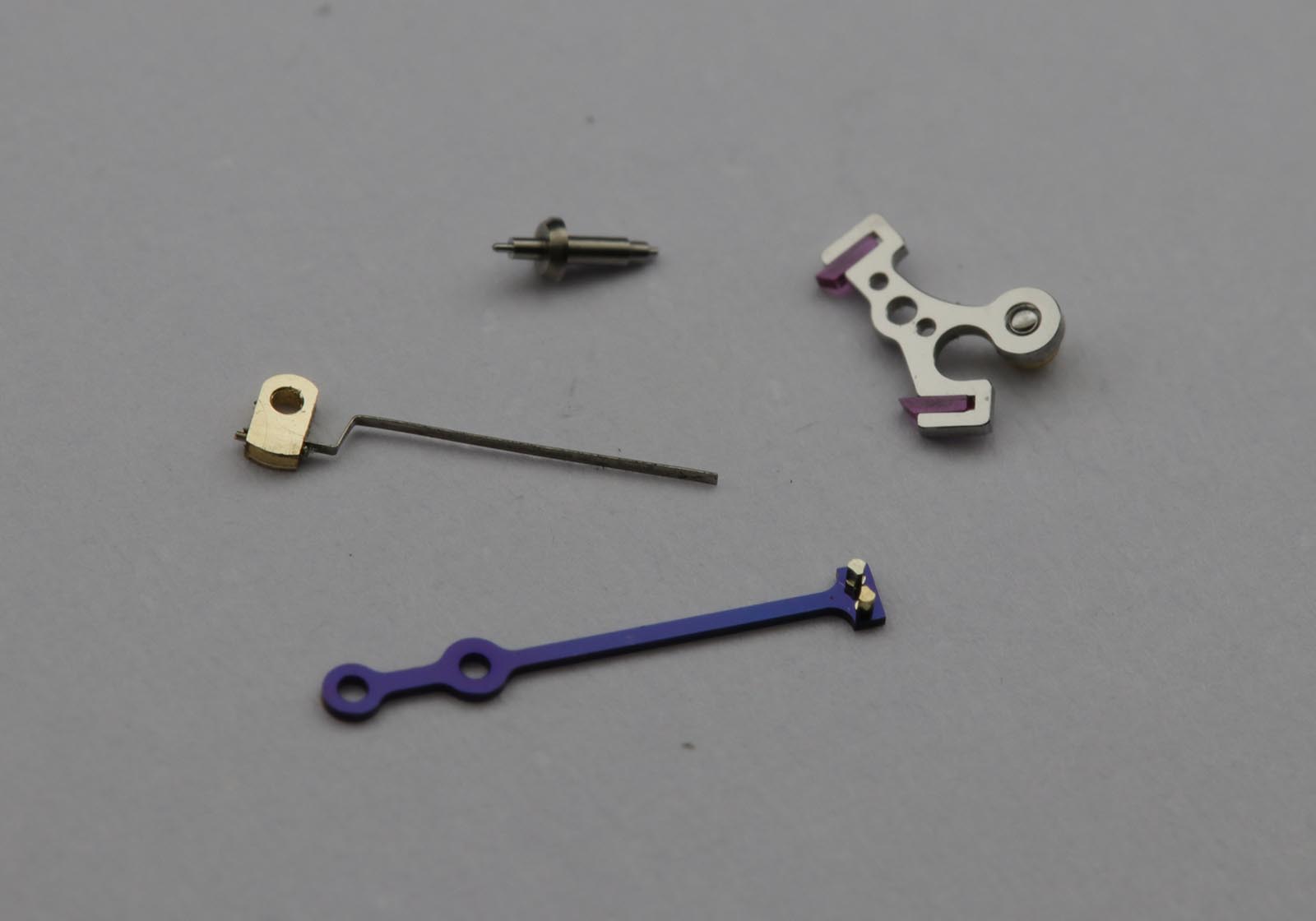

The 12-part pallet lever. Photo – Brivet-Naudot

The pallet lever partially dissembled. Photo – Brivet-Naudot

Retaining a fairly conventional pallet lever in the free eccentric escapement was a measured decision made to avoid most of the drawbacks of the detent escapement that was historically found in marine chronometers.

Firstly, the free eccentric escapement is less prone to accidentally unlocking upon shocks; detent escapements can stop dead with shock, explaining why they have only been installed in a handful of wristwatches.

Also, with excessively high amplitude (where the balance wheel travels in an arc far wider than it should), a detent escapement may unlock twice when the balance wheel swings a full 360°, which doesn’t happen in the free eccentric escapement.

The only drawback is of the free eccentric escapement is it appears to not be self-starting, since the escapement impulses the balance only in a single direction. In other words, it would probably require a gentle shake to start, even after the mainspring’s been wound.

But that is arguably a worthwhile compromise to achieve the more robust overall construction, while maintaining precision timekeeping.

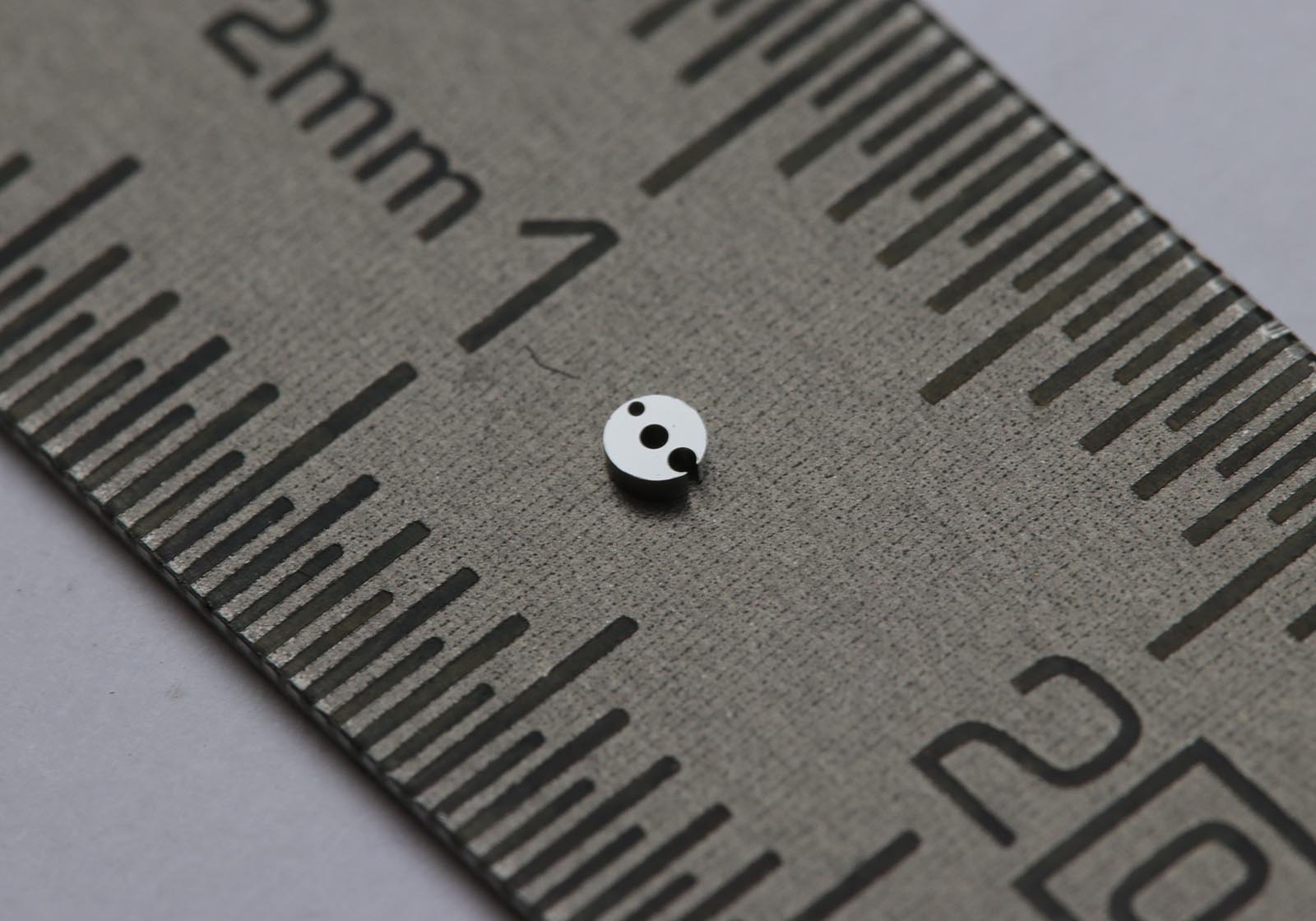

It’s important to note that Messrs Brivet-Naudot and Monnet paid attention to the robustness of the escapement, a quality that is usually absent in exotic, detent-inspired constructions. Even the shape of the small balance roller that engages the long gold spring was designed with less eccentricity compared to the equivalent part in 19th century detent escapements, so the entire balance wheel assembly is less susceptible to shocks.

The small eccentric roller that releases the gold spring. Photo – Brivet-Naudot

The escapement is impressive not only in conception, but also in execution, especially since escapement parts must be manufactured to tolerances within a micron, or a thousandth of a millimetre – 0.001 mm.

Despite the accessibility of modern production methods such as photolithography, Mr Brivet-Naudot opted to produce the parts himself and by hand as far as possible. All 19 escapement components were made using traditional methods and materials – from the cold-working of the gold spring to the cutting of the escape wheel.

Everything else eccentric

As it is with the dial-side of the movement, the parts on the back are finely decorated in an artisanal style. The finishing is finely done and obviously done by hand, but without the elaborate accents found in movements best known for finishing by the likes of Voutilainen or Akrivia. But the watch pictured is also a prototype, and there is no doubt Mr Brivet-Naudot will elevate his finishing with time, given that he has already demonstrated his skill and desire.

Stylistically, the movement is perfectly suited to the philosophy and inspiration of the watch. The layout is reminiscent of pocket watches, while still being unusual and distinct.

Each component of the wheel train is held in place by an old-fashioned finger bridge that has been scaled in proportion to the size of the accompanying component, resulting in a strong visual equilibrium amongst the parts. The pallet fork, for instance, is held in place by the tiniest finger bridge, while the mainspring is secured by a huge bridge.

While the second wheel is visible on the dial side, the third and fourth wheel are located at the back. All of these components, as well as the escape wheel and screw heads, feature the recurring “eccentric” motif of a large and small circle – a testament to the fact that they were made in-house, from scratch. Besides a proof of origin, the unusual detailing also gives the movement a subtle, quirky character that is not often present in the early work of young watchmakers.

An unusual technical detail is the ratchet wheel, which is strikingly small, much smaller than usual. For comparison, the ratchet wheel visible on the back of the Greubel Forsey Signature 1 is two-thirds the circumference of the barrel.

And the reason for that is key winding. Instead of being wound by a crown, the watch is wound with a two-sided key – one just as “eccentric” in style – that inserts into a square slot on the barrel ratchet. Time setting is done with the other end of the key, by inserting it into an “eccentric” slot below the barrel bridge.

While a charming detail in theory – key winding replicates a feature of pocket watches from 200 years ago – winding and setting with a key is inconvenient since it requires, well, a key, essentially something tiny, easy to lose, and difficult to replace.

The Eccentricity with its key in the winding slot. Photo – Brivet-Naudot

Concluding thoughts

The Eccentricity is a remarkable accomplishment both inside and out. The only rub is the price tag of 75,000 Swiss francs, a hefty sum for a time-only watch from a watchmaker new to the scene. But given the tremendous amount of handwork as well as the uniqueness of its design and technical qualities, including a novel, 19-part escapement, the Eccentricity can perhaps be forgiven for its ambition.

Key facts and price

Brivet-Naudot Eccentricity

Diameter: 39 mm

Material: Stainless steel

Water resistance: 30 m

Functions: Hours and minutes

Winding: Key-wound

Frequency: 18,000 beats per hour (2.5 Hz)

Power reserve: 40 hours

Strap: Brown alligator

Availability: Direct from Brivet-Naudot

Price: 75,000 Swiss francs

For more information, visit Brivet-naudot.com.

Back to top.