Complicated Collectors: James Ward Packard

A private laboratory of time.

On 27 April 1927 a nurse walked into a room at the Cleveland Clinic carrying a leather case. The patient was sixty-four, a section of skull removed, the ache of radiation still working behind his eyes. On the charts he appeared as James Ward Packard, co-founder of Packard Electric and Packard Motor Car Company.

To the nurse he was a difficult case. To Geneva he remained the client for whom Patek Philippe had just completed movement number 198’023, an astronomical watch that had absorbed three years of calculation and bench work.

James Ward Packard. Image – Lehigh University Photograph Collection

Inside the case lay a carillon minute repeater on three gongs, coupled to a full perpetual calendar with moon phase, equation of time, and sunrise and sunset indications calculated for Warren, Ohio. On the reverse, a deep blue sky disk carried five hundred and twelve gold stars, turning at sidereal speed around a small Polaris. The sky above his birthplace had been compressed into a circle of lapis and gold, moving in his hands as it moved above the town where he had been born, built factories, endowed an engineering laboratory, and which he now understood lay beyond any realistic hope of return.

Consolation held little appeal for him. Packard placed his trust in precision, in the ability to describe a situation so exactly that it became bearable. The watch answered a question he had circled since childhood: if the world always exceeds your grasp, can you still know, to the minute, where you stand in relation to it. The astronomical watch translated distance and absence into something that could be wound each morning and consulted at will. Longing turned into a calculation on a dial.

The diary as armour

In 1874 Packard was an anxious eleven-year-old boy on a big ship, sent to Europe on a six-month Grand Tour with family friends. The plan aimed at refinement: cathedrals, galleries, a layer of continental culture over a provincial Ohio childhood. For a child away from his mother for the first time, the experience carried a different charge. London, Liverpool, Paris, Rome became waypoints on an itinerary shaped by adults. Streets unfolded in languages he did not speak. In hotel parlours the conversation flowed over him and around him; he might as well have been another piece of luggage set down in a corner.

Almost by instinct he found that numbers could act as shelter. The diary he kept on that trip survives in family papers. It hardly resembles the usual child’s travel journal. “Left London at quarter of three and to Liverpool at quarter of eight, 201 miles.” No remark on the colour of the Thames, no sketch of St Paul’s, only departure time, arrival time, distance.

The pages feel less like homework and more like a first trial of a method that would shape his entire life. Whenever scale and novelty pressed in, he pulled experience back into the safety of measurement. By the time he returned to Warren he had learnt a lesson that outlasted every cathedral and gallery on the itinerary: a journey turned into a sequence of clock times and distances became something survivable.

The engine that whispered

Two years later, in 1876, he stood in Machinery Hall at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition and watched the future turn. The Corliss engine dominated the building: seventy feet long, a flywheel thirty feet in diameter, twin forty-inch cylinders feeding fourteen hundred horsepower into miles of overhead belts that drove every machine in the hall. Presidents and emperors had pulled its levers on opening day. Crowds came to stare.

Machinery Hall at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition. The Corliss at the center. Image – Library of Philadelphia

What stayed with him was the quiet. Instead of clanging itself apart, the engine moved with heavy grace. The flywheel spun so evenly that a guard could sit beside it reading a newspaper. Noise and vibration sank below the threshold of alarm. Raw power emerged as a regulated flow. To a boy who had just crossed Europe by counting railway miles, the Corliss offered a kind of revelation.

Here stood proof that enormous forces could be tamed through design, that chaos could be guided into predictable motion by valves, governors and careful machining. He would spend the rest of his life pursuing smaller versions of that promise, from the vacuum pumps and gearboxes he designed to the watch movements he specified and commissioned from Geneva, laid out in gold on his desk.

Elsewhere on the fairgrounds, in the long gallery devoted to Swiss horology, Patek, Philippe & Co. had sent what Geneva papers described as a “superb collection” of pendant-wound watches and technical showpieces, displayed under Tiffany & Co.’s banner. The small keyless movements embodied the same idea of obedient energy, expressed in miniature.

The boy who listened to the Corliss whisper through its revolutions wandered through an exposition where the name that would later fill his watch cabinets already appeared, demonstrating that precision did not depend on scale.

Creating perfect emptiness

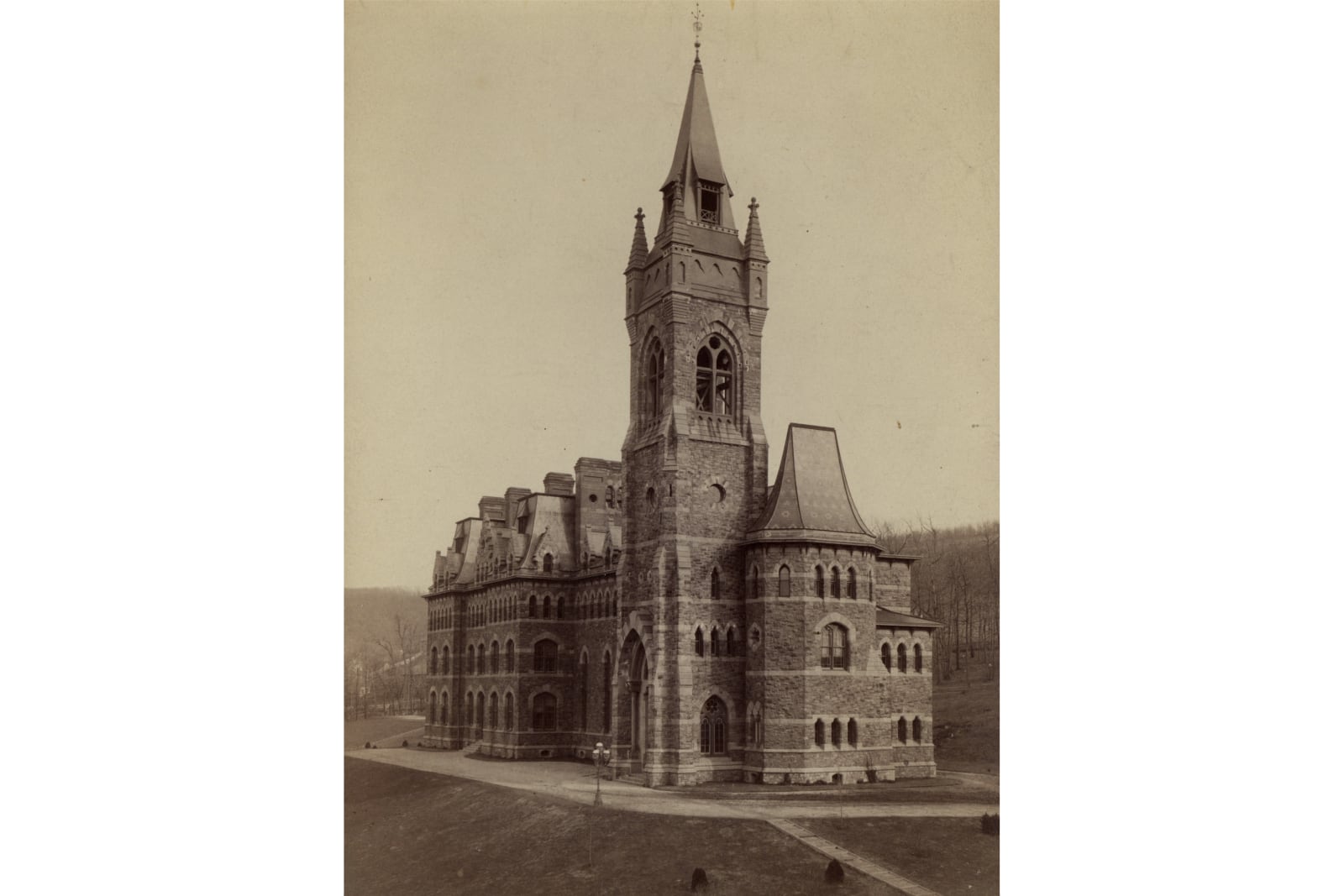

Lehigh University gave him the technical language for what the Corliss engine had suggested in outline. He arrived in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania in 1880 as one of the youngest students in the mechanical engineering programme and treated his dormitory as an extension of the laboratory, wiring his room with bells, switches and improvised telegraph circuits, so that a board by his bed controlled lights and signals throughout his small domain.

Leigh University, ca. 1880. Image – Leigh University

His senior thesis, Design of a Dynamo Electric Machine, trained him to think in flux densities and field strengths, in the relationship between current, voltage and mechanical work. After graduation in 1884 he carried that mindset to New York and the Sawyer-Man Electric Company, where the incandescent lamp war with Edison reached full intensity. The problem on his bench came in a simple outline and stubborn practice: a carbon filament sealed in glass burns out unless the air vanishes from the bulb. Existing pumps worked slowly and left too many residual gases; filaments failed after only a few hours.

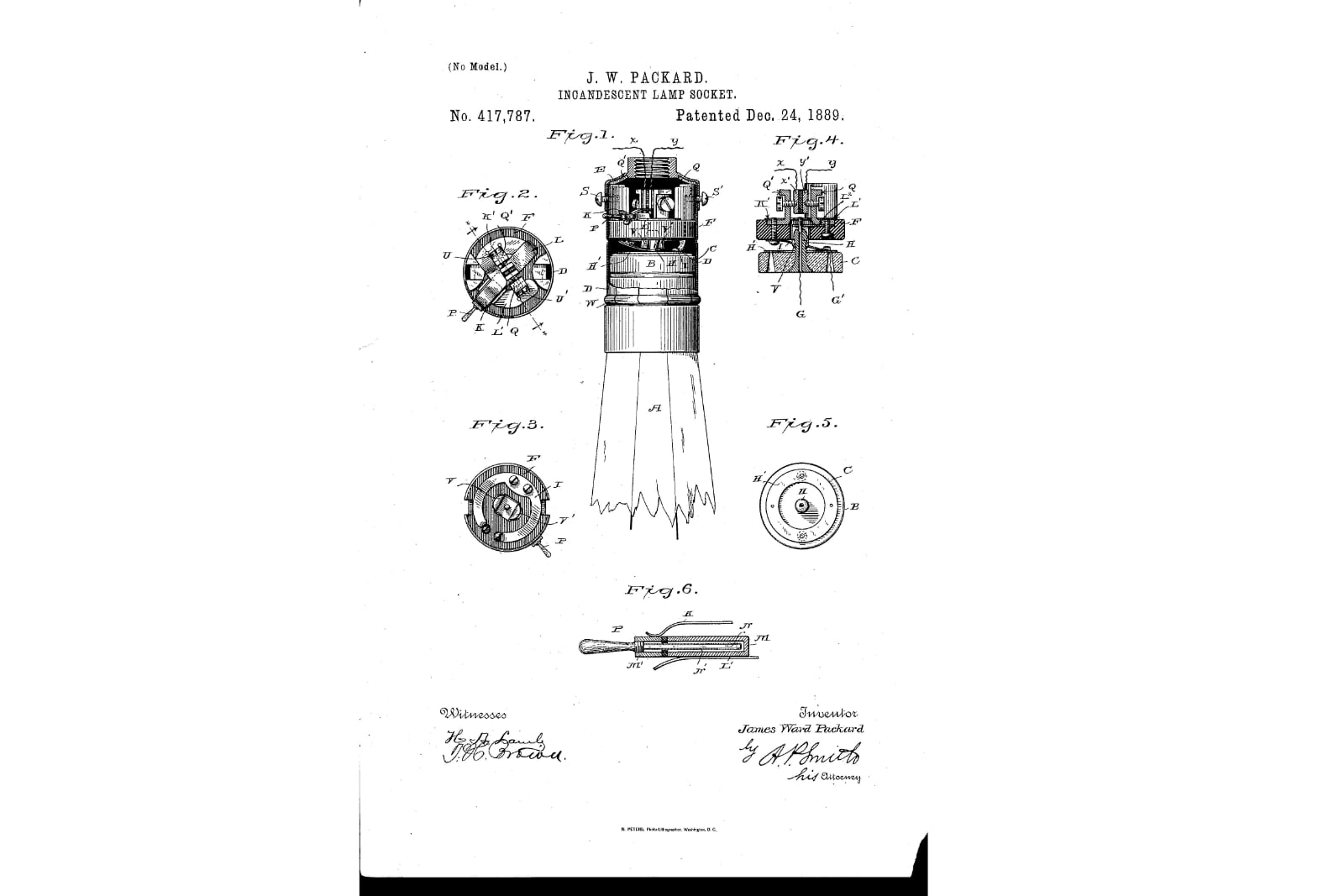

Packard’s answer was the vacuum pump that carried his name. The machine evacuated bulbs faster and to a lower residual pressure than competing designs, leaving so little oxygen in the glass that filaments could glow for hundreds of hours. By 1891 the “Packard pump” sat as standard equipment in American lamp factories, a tool that fixed the internal condition of a bulb so precisely that lamp life could be predicted and guaranteed. In his mind pressure, current and filament behaviour linked together in a calculable way.

J. W. Packard’s incandescent lamp patent from 1889. Image – Wikipedia

During these years he began buying watches: a Victor Kullberg chronometer with minute repeater, an enamelled watch signed Guex à Paris, an 18k verge by Chevalier. They fell short of a collection in the later sense; they functioned as case studies. Each one represented a different way of storing energy in a spring, releasing it through an escapement and translating that flow into sound or motion. The dynamo room and the lamps paid the bills. The watches formed pieces of a private seminar in power management, scaled down to the size of a pocket.

Cars, hills and a pocket laboratory

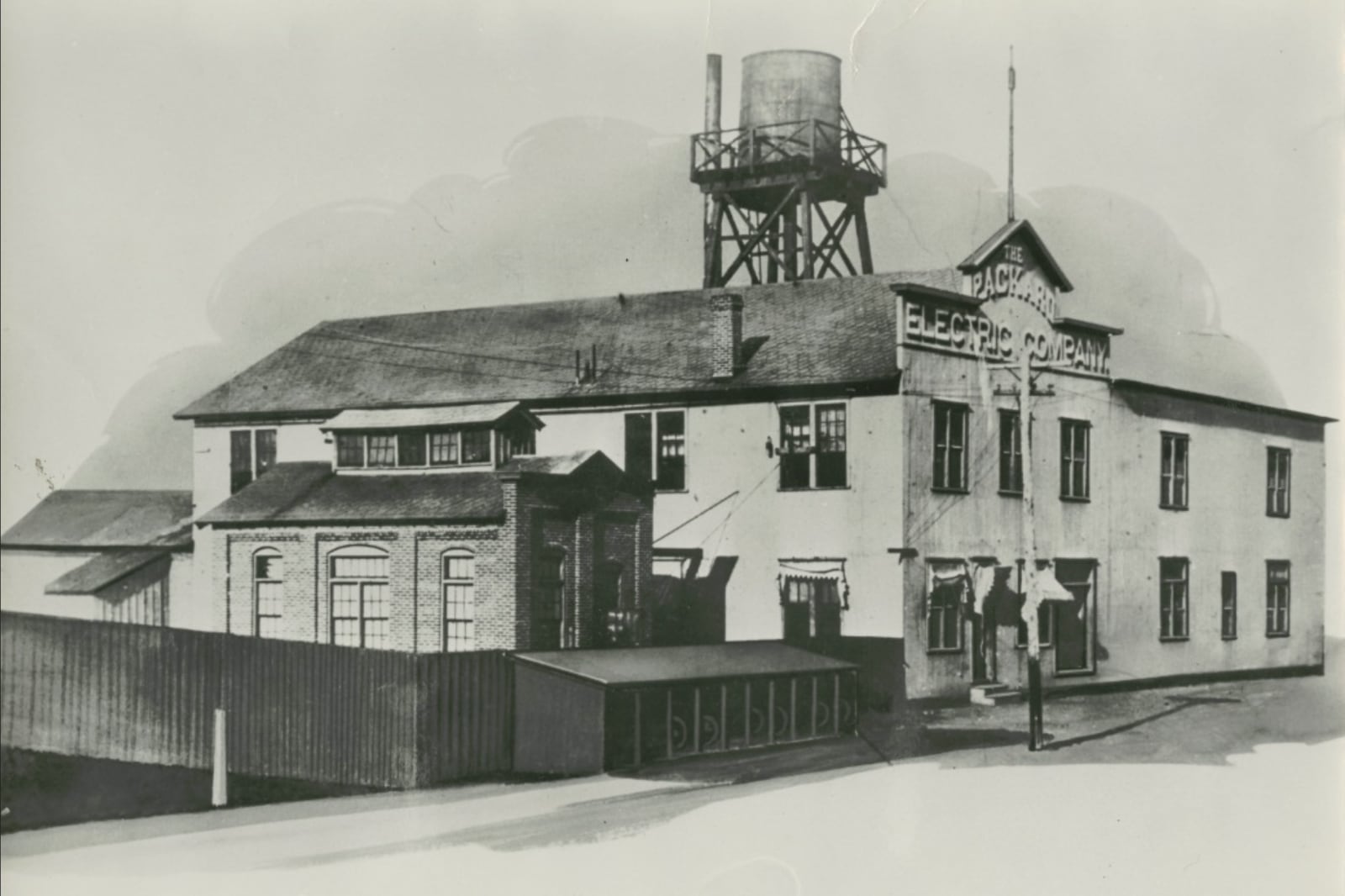

In 1890 he returned to Warren. The vacuum pump and his record as a factory manager had given him weight with investors. With his brother Will he founded the Packard Electric Company, and a few years later the New York & Ohio Company, which handled transformers and other apparatus, but it was the emergent automobile industry that would draw his attention.

The Packard Electric Company Plant in Warren, Ohio, ca. 1890. Image – New York Heritage Collection

His foray into the automobile business began in 1898 when he bought a Winton. On hills it faltered, on rough roads it overheated and shook itself apart. Packard wrote to the maker with a list of faults. Alexander Winton answered that anyone who felt capable of improvement should build his own car. Packard took the remark as an instruction. Five years later, the Packard Motor Car Company opened its factory in Detroit.

The early Packard cars demanded measurement. Road tests around Warren and Detroit took place on rough surfaces, with unreliable fuel and anxious passengers. Packard marked mileposts, timed hill-climbs with passengers aboard, and logged the results in neat columns. Others spoke about how powerful or sluggish a car felt; he wrote down how long it took to cover a given distance uphill with three men aboard.

James Ward and his wife Elysabeth Gilmer Packard in an early Packard car. Image – Wikipedia

He turned to Geneva at the same moment the cars began to carry his name. In 1905, while he still shuttled between Warren and Detroit, he ordered from Patek Philippe movement no. 125’009, an 18k gold clock watch with chronograph, grande sonnerie and perpetual calendar, his first meaningful commission from the firm.

The watch gathered into one case the questions that occupied his working days: the striking train turned stored power into sound on demand, the calendar traced long cycles of months and years, the chronograph broke journeys into measurable intervals. In his study it behaved like an instrument of record, a compact mechanism that handled time in the same analytical way he approached hill-climb runs, lamp life and engine behaviour.

Patek Philippe no. 125’009 with perpetual calendar, chronograph with 60-minute register made in 1905. This is the first known watch to have been sold to Packard. Image – Patek Philippe/collage

Through the next decade he lived in two overlapping worlds. At the Detroit factory he worked with Joy and the engineers on gear ratios, engine smoothness, chassis stiffness. At his desk in Warren he wound watches that compressed the same concerns into springs and levers.

As he gradually relinquished day-to-day control of Packard Motor after 1909, the watch commissions began to take over the space that cars had once filled. The Kullberg chronometer and the English grands complications from S. Smith & Son gave him British benchmarks. The early Patek Philippe commissions showed what Geneva could achieve when asked for elaborate chiming and calendar work. The boundary between his industrial and horological lives grew thin.

The programme in gold

Patek Philippe movement no. 174’129 Grand Complication, 1916. Image – Patek Philippe/collage

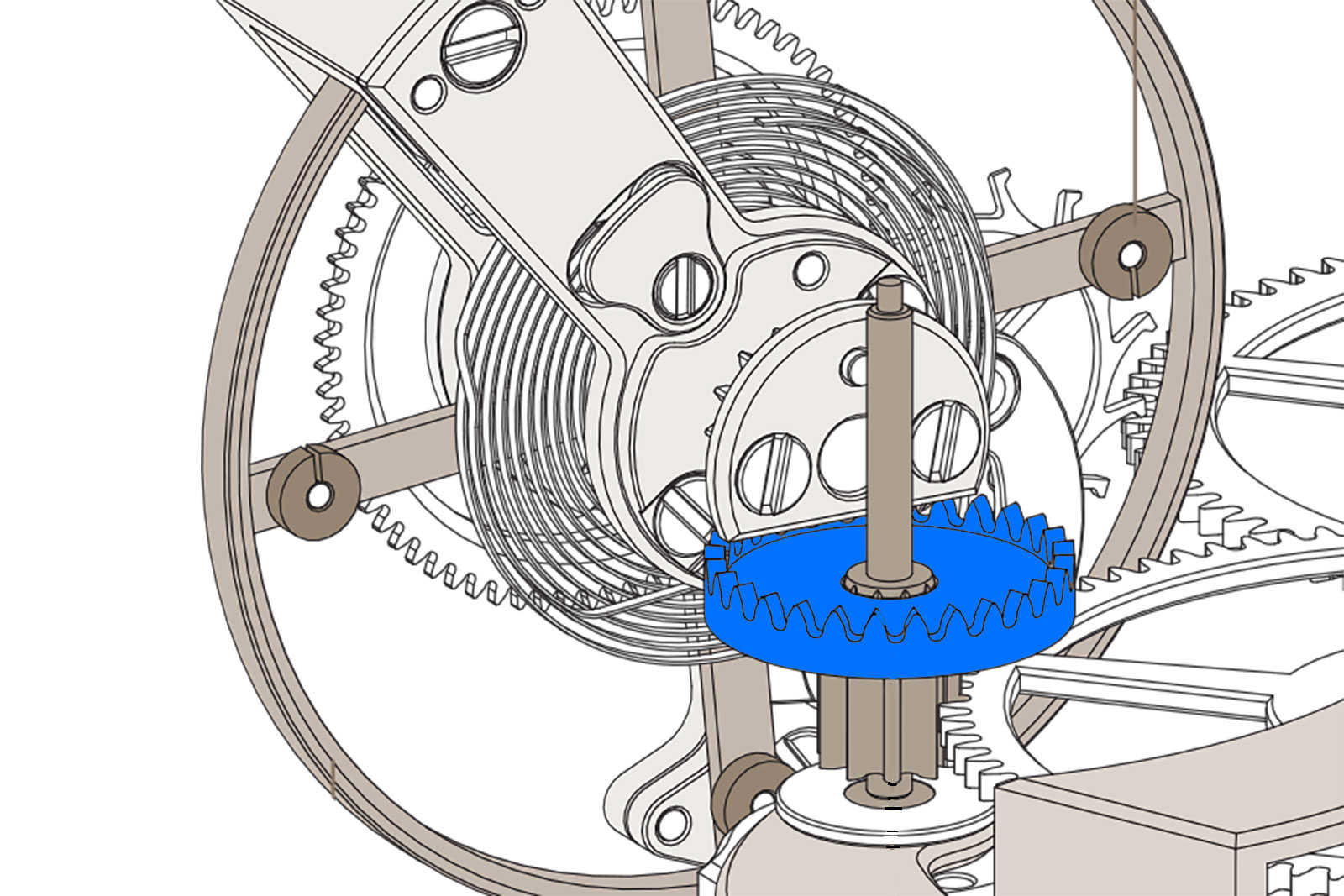

In 1916 Patek delivered movement no. 174’129, a grand complication that still reads as a manifesto. Sixteen functions: grande and petite sonnerie, minute repeater, perpetual calendar, moon phase, split-seconds chronograph, a jumping-seconds train and twin power-reserve indicators. The foudroyante hand, a small seconds pointer that makes five jumps each second, cuts every tick of the main train into visible slices.

When the Horological Institute of America (HIA) later placed it in a showcase as Exhibit No. 12, it chose to single it out as “a great masterpiece of mechanical construction and artistic workmanship,” an exemplary specimen of the “combination type” watch in which multiple mechanisms coexist in one movement.

Patek Philippe movement no. 174’623 eight-day equation watch with sunrise and sunset indications, 1917. Image – Patek Philippe/collage

A year later came movement no. 174’623, the eight-day equation watch with two trains, perpetual calendar, and sunrise and sunset marked on sector scales. In the context of Packard’s notebooks it feels like the next inevitable step.

The boy on the Liverpool train had reduced journeys to miles and minutes. The student at Lehigh had learnt to compute dynamo output. In late middle age he could carry in his pocket a device that told him each day exactly how civil time in Warren diverged from the sun’s behaviour and when light would reach and leave his own front door.

Patek Philippe movement no. 174,720 tourbillon with minute repeater, 1919. Image – Patek Philippe/collage

Alongside these projects, the English pieces he had assembled continued to serve as reference points. The tourbillons and observatory-grade chronometers, checked and re-checked, came from a world where an observatory-tested tourbillon already counted as a rare prize; together they gave him a line of expectation for rate and stability against which any new idea from Geneva had to hold its own.

Vacheron Constantin no. 375’551 with trip repeater, grande and petite sonnerie, half-quarter striking and chronograph, ca 1917. Image – Christies/collage

During these same years he began to work with Vacheron Constantin in a more deliberate way. An early commission brought him an 18k gold open-face watch in 1912, a relatively straightforward piece that established a line of communication and gave him another benchmark in daily use.

By 1917 he felt ready to ask for something less conventional: the 20k landscape watch, no. 233’573, ordered that year and delivered in 1919, with a case in high-carat gold, one dial engraved and another in enamel showing a house in a garden, and a subsidiary seconds dial set into the scene. The movement sat under an exterior that treated the watch almost as a miniature panel painting, an essay in how far decoration could go while timekeeping still remained central.

That same year he received from Vacheron the massive 20k gold chronograph with movement no. 375’551, a piece that united trip repeater, grande and petite sonnerie, half-quarter striking and chronograph in one case. The chiming sequence was arranged so that hours, quarters and the extra seven-and-a-half-minute strikes each had a recognisable voice.

Patek Philippe No 174’907 minute repeater with up-and-down indicator, 1920. Image – Patek Philippe/collage

Viewed through the HIA catalogue, the full group divides clearly. Just under half of the 30 exhibits it displayed under his name were Patek Philippe. Around them, Packard placed English grand complications and chronometers from S. Smith & Son, Dent and Benson, including massive fusee tourbillon chronographs with Kew certificates and Admiralty trial records, along with a watertight explorer’s watch and detent chronometers of a type polar explorers might have carried.

By the early 1920s, the group of watches on his desk and in his pockets reads less like an assortment of expensive objects and more like a survey of scientific inquiry.

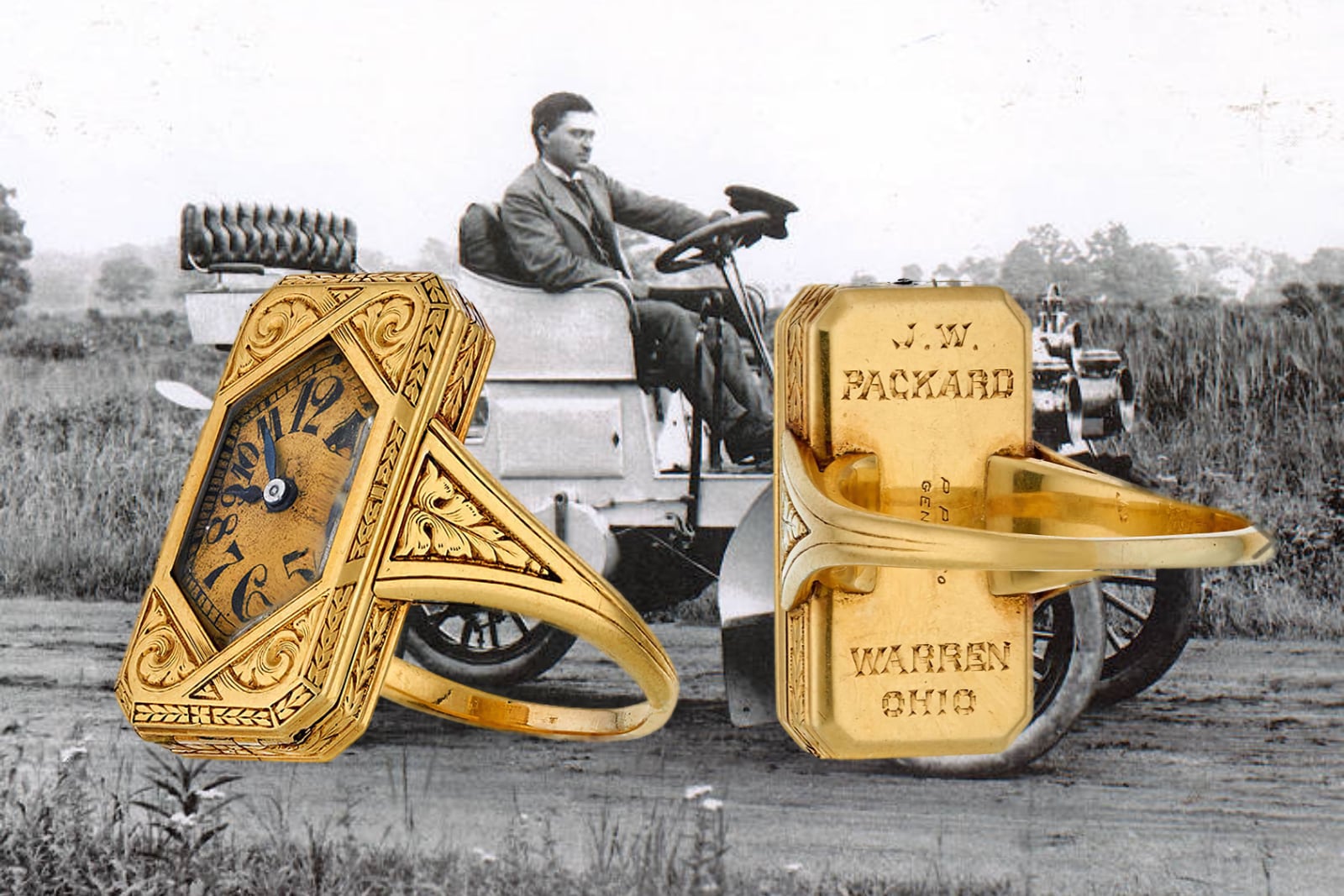

Wearing instruments

As his commissions deepened, the watches moved closer to his body. Patek Philippe movement no. 174’659, the ring watch, compressed a complete keyless movement into a signet. A slight rotation of the hand sufficed to read the time, avoiding the gesture of drawing a watch from a pocket.

Patek Philippe movement no. 174’659 ring watch. Image – Patek Philippe/collage

Patek Philippe’s movement no. 174’826, the cane watch of 1918, pushed ergonomics further. Every evening in Warren he walked the railway line, counting ties, judging distance, logging pace in his notebooks. A pocket watch required a pause. A dial set into the silver knob of an ebony cane let him read the time in stride.

Patek Philippe movement no. 174’826 cane watch, 1918. Image – Patek Philippe/collage

The ship’s-bell clock watch, Patek Philippe movement no. 174’876 delivered in 1920, drew on sounds that belonged to water and watch together. On ships and lake steamers the day comes in four-hour watches, marked by bells: one at half an hour, two at an hour, up to eight at the end. The sequence tells crew and passengers where they stand in the watch without any need to look at a dial.

Patek Philippe movement no. 174’876 ship’s-bell clock watch, 1920. Image – Patek Philippe/collage

By then Packard’s life ran between Warren and his house at Chautauqua Lake, where boats and launches formed part of the setting; Patek Philippe compressed that maritime pattern into a pocket watch.

Yacht christened Manana owned by James Ward Packard underway on Chautauqua Lake. Image – Lakewood Historical Society

Sound and the missing voice

As the programme of pocket watches expanded, sound captured more of his attention. He had spent his working life among industrial noises, from the hiss of pumps in lamp factories to the layered note of car engines at different loads. Repeaters and sonneries translated some of that experience into chimes that lent themselves to scrutiny. In the 1920s he began to ask for pieces where acoustic behaviour and daily use came together more deliberately.

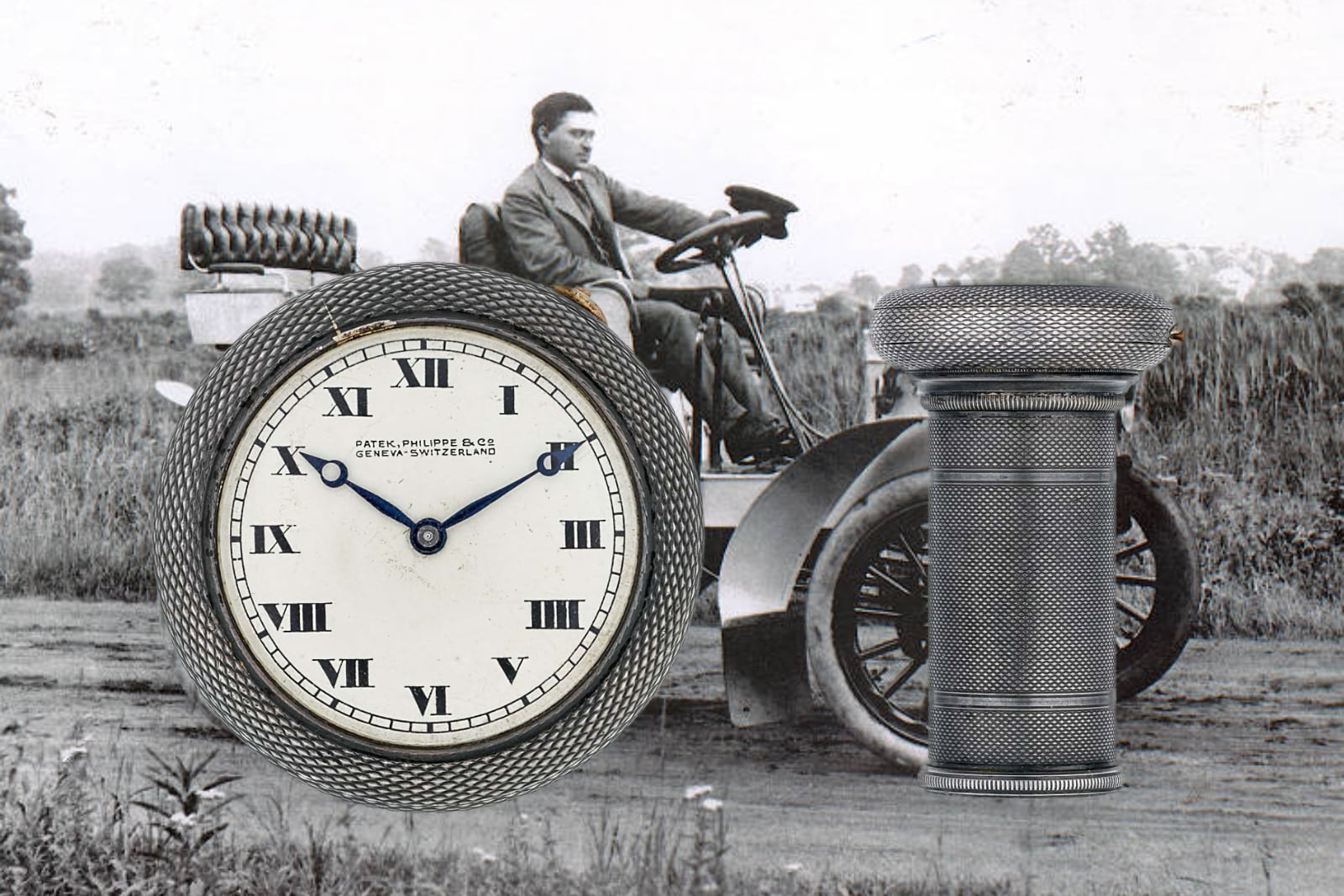

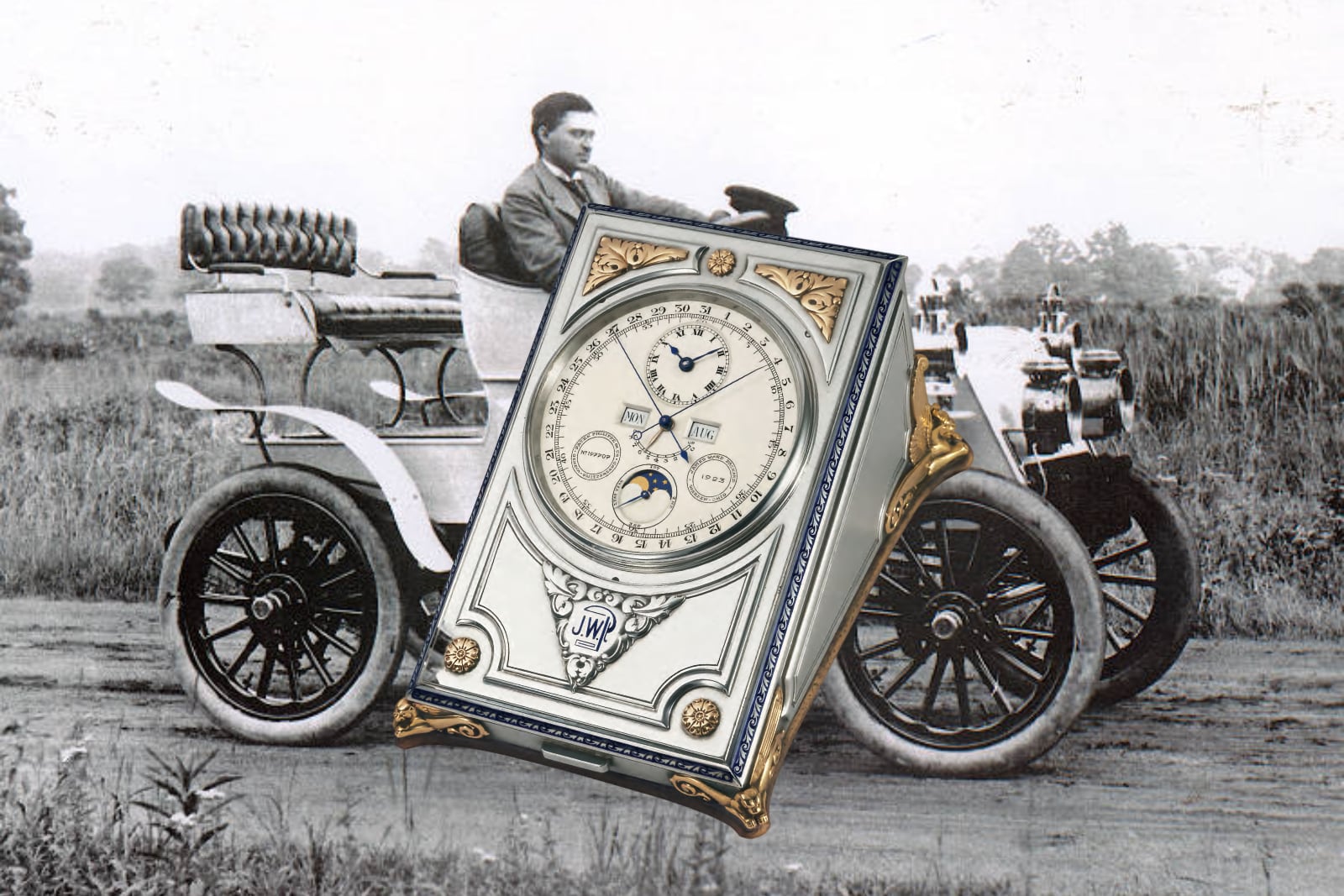

Patek Philippe movement no. 197’707 Presse-papiers desk clock, 1923. Image – Patek Philippe/collage

The presse-papiers desk clock, Patek Philippe movement no. 197’707, belongs to this phase. Delivered in 1923, it is a compact, heavy clock in a low silver case with gold details and his monogram engraved beneath the glass.

Inside sits an eight-day movement with double barrels driving a perpetual calendar, moon-phase display, leap-year indication and power-reserve sector. The striking work can repeat the time on demand. On his desk at Oak Knoll it acted as a quiet regulator of rhythm, a visual reminder of the link between winding, duration and rate that had occupied him since his lamp and dynamo years.

Patek Philippe movement no. 197’791 clock watch with carillon, 1924. Image – Patek Philippe/collage

In March 1927 Patek sent a different chiming piece, the musical alarm, movement no. 198’014. At first glance it looks like an oversized gold repeater, closer in weight to a deck watch than a conventional pocket watch.

The difference lies behind the dial. Instead of a simple alarm hammer, a pinned cylinder drives a tuned steel comb, playing the berceuse from Benjamin Godard’s Jocelyn when the alarm trips. The choice of melody was specific: a lullaby his mother had valued.

Patek Philippe movement no. 198’014 musical alarm, 1927. Image – Patek Philippe/collage

The Jocelyn watch takes a piece of family memory and folds it into the same language of pins, teeth and springs, showing that by the late 1920s the material reaching his desk already carried emotional freight as well as answers to abstract questions of power reserve or striking sequence.

Patek Philippe movement no. 174’749 with perpetual calendar, Westminster carillon and double power reserve, 1925. Image – Patek Philippe/collage

The portable sky

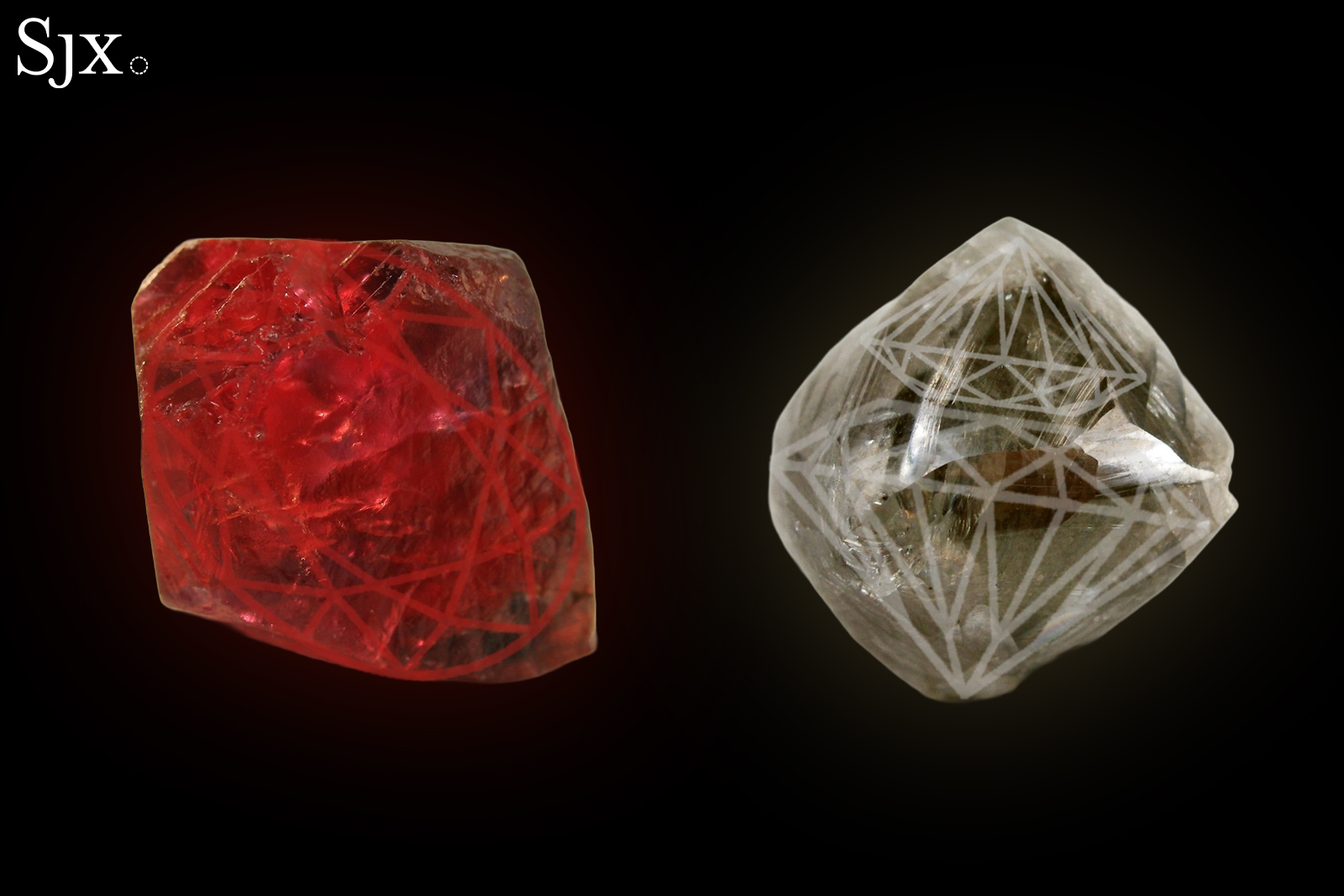

All of this leads back to the astronomical watch that entered the story at the beginning, the piece that reached him in the Cleveland Clinic only weeks before his death. Patek Philippe movement no. 198’023, completed in 1927, gathers into one case almost everything he had been asking from Geneva for two decades.

The front dial carries civil time, perpetual calendar, moon phase, equation of time, sunrise and sunset for Warren; a ten-complication layout that reads as a summary of his interests in rate, reserve and the relation between clock and sun. On the reverse, a rotating sky disk in deep blue enamel shows the stars above Warren at 41 degrees 20 minutes north, 80 degrees 48 minutes west, moving at sidereal speed around a fixed pole.

Patek Philippe “The Packard” no. 198’023 double-faced with 10 complications completed in 1927. Image – Patek Philippe/collage

Within the history of watchmaking, this watch occupies a specific position. In modern horology, the Leroy 01, made for António Augusto Carvalho Monteiro, had introduced a portable celestial chart in 1904. Packard’s watch came next, taking the same principle and applying it to a sky calculated for an American town where a hardware store, an electric company and a car factory had grown.

After the engineer

Death turned his instruments into property. The same probate process that counted his shares and real estate also had to assign a number to watches without real comparables. Most of the watches would end up in the hands of Packard’s preferred beneficiary, the HIA.

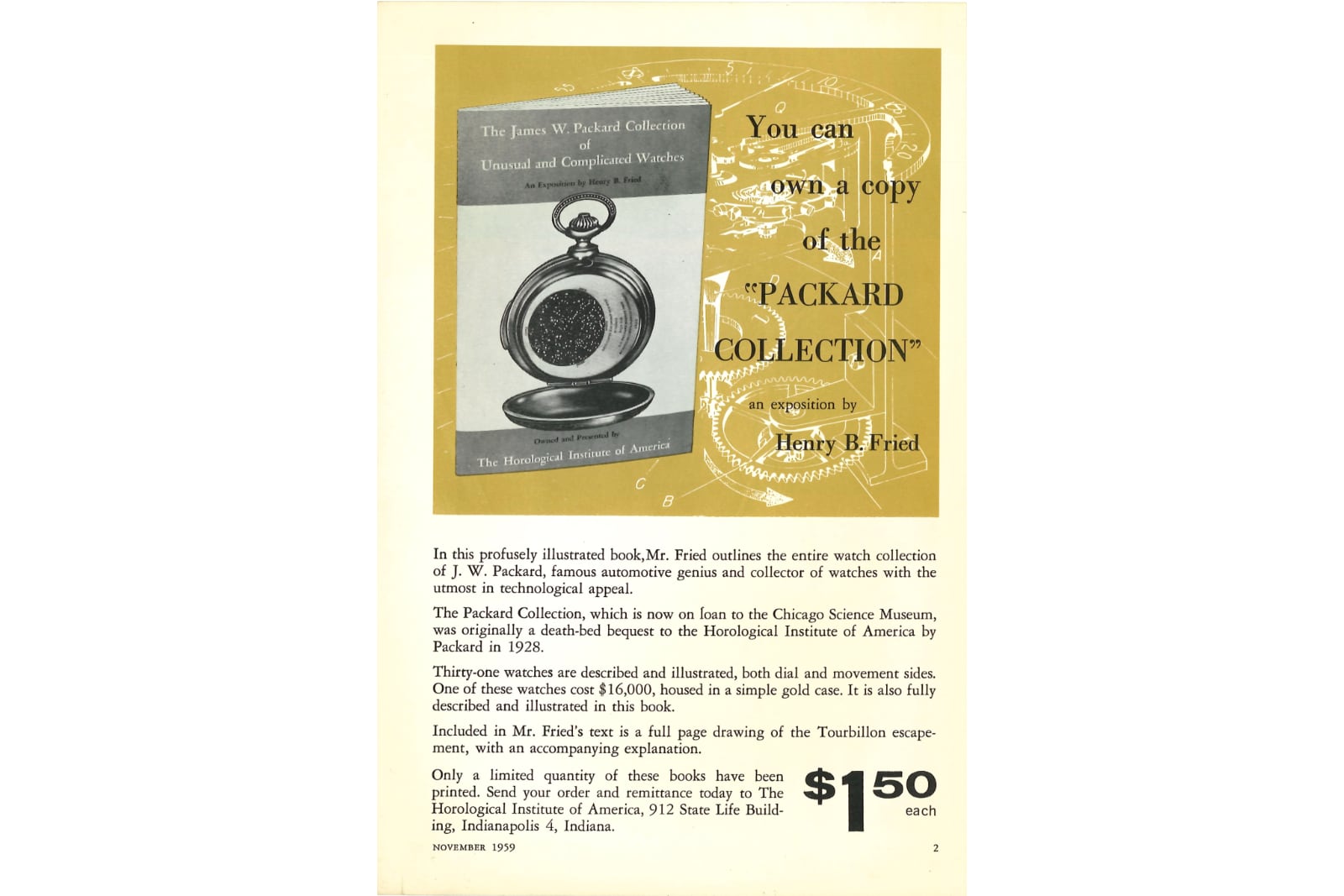

The HIA at once framed the watches as a teaching collection, publishing a brochure that described them as an example of “the highest development of human ingenuity as applied to horological mechanisms”, acquired from a mechanical engineer whose own career showed what disciplined curiosity could achieve.

The “Packard Collection” booklet produced by Henry B. Fried in 1959. Image – The HIA Journal of Modern Watchmaking

After keeping the watches in the public eye for decades, the HIA faced a difficult landscape by the 1980s. Quartz technology, changing patterns of training and limited resources pushed it towards a choice. It needed capital, and the Packard watches were its most liquid assets.

In 1988 the HIA sold four of them, including the astronomical watch, to seed a perpetuation fund. Patek Philippe, preparing its 150th anniversary and thinking about a museum, acquired no. 198’023 and brought it back to Geneva. The watch that had crossed the Atlantic to reach a hospital bed in Ohio crossed it once again to become P-704 in the Patek Philippe Museum.

Other pieces followed quieter routes, dispersed into a small constellation of private collections and brand archives, while a handful of watches stayed in Packard family hands for decades in a safe-deposit box. In 2011, Christie’s brought them to market in New York under the heading “Property from the Collection of James Ward Packard”.

For many collectors this sale offered the first time the name on the dial and the story on the page met in a tangible way. Among the various watches sold, the Vacheron Constantin, with its JWP cartouche and rich gold relief work, crossed the seven-figure line.

A rivalry, debunked: Henry Graves Jr.

In the late twentieth century a different story grew around this material. Patek Philippe, emerging from the quartz crisis, began to frame two American patrons as antagonists in a polite race: James Ward Packard and Henry Graves Jr. The symmetry helped. Both came from the United States. Both ordered astronomical watches. Both had their names attached to pieces that later set records. From symmetry it took little effort to reach the idea of rivalry.

The narrative worked well for marketing and auctions. When the Graves Supercomplication came up for sale in 1999 and again in 2014, catalogues and articles leaned on the image of an arms race in complications, a back-and-forth between the engineer from Warren and the banker from Fifth Avenue. That frame helped the Supercomplication carry estimates and hammer prices that echoed far beyond the watch world.

Henry Granes and James Ward Packard. Image – Wikipedia/collage

The surviving paperwork offers a plainer view. Packard and Graves moved in different social circles and left no trace of direct contact. Packard’s major Patek commissions sit between 1905 and 1927, with the 1916 grand complication and the 1927 astronomical watch as poles. Graves’s deepest engagement with complications begins around 1919 and crests with projects finalised after Packard’s death. When Patek’s technical staff drew the Supercomplication, the obvious benchmark lay in Paris, in the Leroy 01 of 1904.

The contrast between the two collectors matters. Graves assembled the apex of what workshops offered: supercomplications and observatory champions that had already proved themselves at Neuchâtel or Geneva. His taste belongs to a connoisseur culture that prizes best-in-class status. Packard commissioned objects that behaved like research tools.

The questions he posed to Geneva grew directly from his own life and professional instincts. Graves sought the summit; Packard sought experiments. Their watches now sit a few steps apart in Geneva and in the literature, yet they speak distinct dialects.

The Packard legacy

Strip away auction headlines and brand narratives and Packard’s importance settles into the continuity of his method. The boy who turned journeys into tables of distances and times became the engineer who asked Geneva for instruments capable of probing mechanical limits in a structured way.

For contemporary independent watchmakers, his story offers a working pattern for collaboration: a patron who treats a workshop as an extension of his own laboratory, and workshops that respond with coherent sequences of ideas rather than isolated showpieces.

For collectors, his scattered watches show what provenance can reveal when it points to a mind asking specific questions, instead of only pointing to a celebrated name in a catalogue heading. For historians, his bequest to the Horological Institute of America and the later dispersal of the collection trace how technical culture moves through teaching collections, funding pressures, and eventually institutional museums and private holdings.

The image that remains at the end is the hospital room in 1927, an engineer in his sixties turning an astronomical watch under bright clinical lights, thumb passing over an engraved outline of the hills around Warren, listening to a chime sequence he had approved years earlier at a desk in Ohio; the very existence of the watch a byproduct of a life spent insisting that questions about distance, rate and position deserve exact answers.

The watches that left Ohio for the Horological Institute, then for Geneva, then for other safes and display cases, sit inside that same framework. At the end of that line stands a double-faced watch that describes the sky above a town he could no longer reach. That movement, still turning in Geneva, keeps sidereal time for a place its first owner left for the last time in 1927 and remains a precise record of the way he chose to think about the world.

Back to top.