In-Depth: The Bespoke (and Custom) Experience at Andersen Genève

The long road to exactly what you want.

When applied to watches, “bespoke” brings to mind the ultra-complicated timepieces made for famous historical figures like James W. Packard and Henry Graves Jr., who each commissioned a succession of one-off watches that pushed the technical boundaries of watchmaking in the early decades of the 20th century. One of those watches, the landmark Patek Philippe “Supercomplication” made for Graves, long held the title of most-expensive-watch ever sold.

In the modern day, watchmakers continue to create unique watches. Patek Philippe does it quietly for its best clients, while Vacheron Constantin is more public with its Atelier Cabinotiers department that specialises in customised timepieces. Similarly, artisanal independent watchmakers like Voutilainen often accept commissions.

But as a collector, how easy is it to dip your toes into the waters of bespoke or custom watchmaking? This is my maiden experience with such watches, which started at Andersen Geneve some six years ago.

Svend at work

Industrial vs. artisanal

I first wanted to get involved in the creation of a custom watch in 2014. I already knew then it could not merely be changing colours on the dial or hands, neither could it be an engraved monogram. What I wanted was a truly unique world-time watch with a Louis Cottier-type mechanism.

At the same time, I had a certain budget in mind, so I approached independent watchmakers that made watches I liked, but with steel cases. Somewhat naively, I thought adding a time-zone function would be straightforward and not too expensive, essentially something I could write off without too many sleepless nights if things didn’t work out as planned.

I made enquiries with the exhibitors the AHCI booth at Baselworld that year – and had no luck. In hindsight, I realised one of the major obstacle was the budget. It is not possible to offer a truly bespoke watch while maintaining a proportionately-reasonable premium relative to the retail price of the standard model, especially when the watchmaker relies on suppliers who produce components on an industrial scale.

Such industrial production leads to zero economies of scale for custom watches, since such watches are, by definition, one-off creations. So making a custom watch with industrially-produced parts means fixed overheads that are ordinarily amortised over hundreds, if not thousands, of components, are instead applied to just one unit, resulting in an an astronomical inflation of the price. As a result, I had to shop more smartly and seek out a more cost-efficient approach to one-off watchmaking.

To improve my chances of success, I also increased my budget by a sum equivalent to the typical premium to go from a steel to an 18k gold watch case, or about 10,000 Swiss francs. That brought my budget to 50,000 francs. And with that I found a willing master watchmaker – Svend Andersen of Andersen Genève.

The art of Svend Andersen

Turning to Svend for the project was not a random choice, as at the time I already owned all of Svend’s standard-production world-time watches, including several discontinued models. But Svend has only ever made watches in precious metal, so it was not feasible to approach him before I had modified my initial goal of a steel world-time watch.

Now 78 years old, Svend has been making custom watches since 1979 when he established Andersen Genève. And having been inspired by the Louis Cottier-type world time watches he worked on while he was at Patek Philippe in the early 1970s, he introduced his first world-time watches in 1989, and since then they have been part of the catalogue in a variety of forms.

More importantly, Svend and his workshop boast both the skills as well as the hand-operated machines that are necessary for cost-efficient production of single parts, meaning that industrial-scale minimum orders are not needed, allowing him to produce custom or bespoke watches priced within the realm of reason. In fact, the equipment and knowhow possessed by Andersen Genève is the very same required for vintage watch restoration, which is also part of the company’s repertoire.

Svend Andersen gifted the prototype of the world’s smallest calendar watch to noted Swiss watch retailer René Beyer (left) for the Beyer Watch Museum, located in the basement of the eponymous store in Zurich; the calendar functions of the watch are packed into a module just 1.4 mm high that’s installed on an equally petite LeCoultre cal. 104. Photos – Beyer Chronometrie

Svend’s small-scale production is almost always concerned with complication mechanism, rather than the base movement. He instead opts to rely on industrially-produced, high-quality movements as the base, allowing him to keep prices for custom watches bearable. For that reason, the mechanisms for his signature complications – namely world time, calendars, and automatons – are all constructed as add-on modules.

Collectors often have reservations against modular movements, usually in relation to the increased height compared to an integrated complication. Yet Svend has proven time and again that smart construction still allows for extraordinary thinness. His miniature calendar watch for instance, is the smallest calendar watch ever. Another accomplishment is a world time module that’s just 0.5 mm high, which is part of the Mundus, the thinnest world-time watch on the market.

The Mundus is only 4.2 mm high in its entirety; the watch is powered by the Frédéric Piguet cal. 21 while using the underside of the dial as the plate for the world time mechanism to keep the movement as thin as possible. Just 24 in platinum were made in 1993.

The Andersen Genève Communication 750 world time of 2011 that became a unique piece as the model never made it beyond the prototype stage

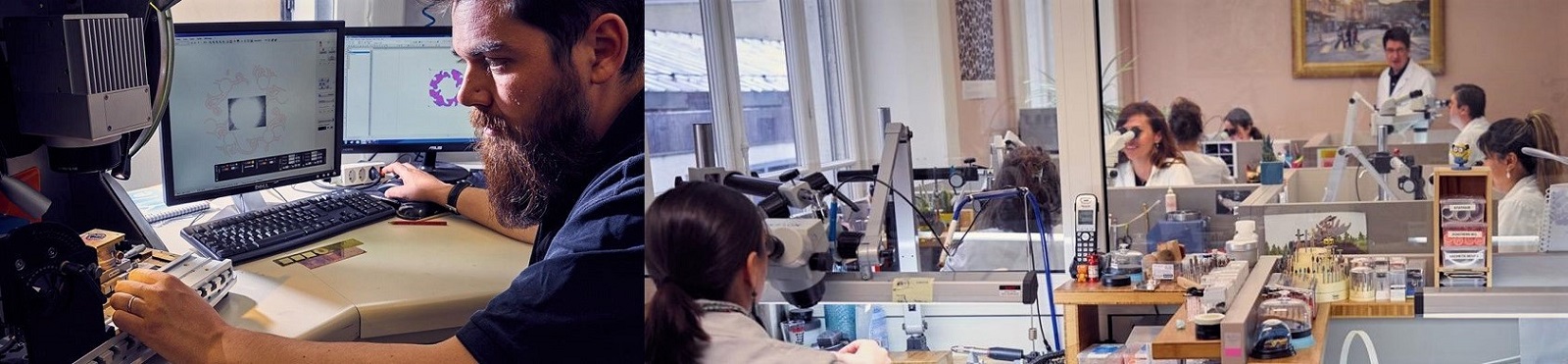

While he does most of the work in-house, Svend acknowledges he has not mastered all the crafts that go into making a watch. And so he calls upon a small group of specialists from time to time, choosing the best artisan for each task. Svend’s collaborative approach means he prefers to work with specialists who can contribute their own ideas to the conception of a watch, rather than just skilfully execute a design.

Friendships and the short distances between most workshops make for efficient communication between Svend and his suppliers, allow them to easily sit down and brainstorm – and the client is always welcome to join in. That has resulted in long-term relationships with a variety of local artisans, including engravers, miniature painters, stone setters, and guillocheurs – a wide pool of talent that means the client obtains the best work in every respect.

One of Svend’s favourite artisans is engraver Kees Engelbarts (left), who is also an accomplished illustrator, which allows the customer to avoid hiring a professional graphic designer

But beyond the making of watches, something that sets Svend apart as person is the tremendous generosity he has shown in passing on his knowledge. Amongst the many watchmakers who passed through his workshop over the decades are Franck Muller as well as Felix Baumgartner of Urwerk, both of whom worked at Svend’s workshop long before they became famous.

The same desire to develop young watchmaking talent also led him to establish the AHCI, along with his peer Vincent Calabrese, in 1985. In that sense, Svend is one of the original independent watchmakers.

The young Franck Muller worked with Svend from 1984 to 1991, and his earliest watches, signed “Franck” and often labelled première mondiale, or “world premiere”, were made in Svend’s workshop

Defining unique

Svend describes each of his custom-made watches as pièce unique, a common label in watchmaking. But often it doesn’t take much for a watch to be “unique”; a minor change of colour on a tiny part usually justifies the accolade.

I myself prefer definitions that Roger W. Smith outlined on an older version of his website, though they have since been removed.

“Unique commissions” were described as “a completely individual watch” that “requires a deep collaboration [with the client]… as well as an existing insight and understanding of [the Roger W. Smith] approach”.

One step down was the next “level of personalisation”, defined as incorporating “details to vary the standard appearance of the existing series watch”, but with the changes limited to “decorative aspects… such as material choice and specialist metal treatments, which can include unique engraving designs”.

In my mind, “bespoke” is appropriate only if I can help formulate the movement and its functions, in addition to the case design. On the other hand, “personalisation” is when I am limited to changing the decoration and graphics of an existing watch in the watchmaker’s catalogue.

Several years ago, I commissioned a pair of Andersen Geneve watches in each of those categories. But instead of moving upwards in the degree of customisation as most would do, I did it in reverse – first bespoke, and then personalised. This is a detailed account of the experience.

Bespoke (left), and personalised

Bespoke – Andersen Genève Retrograde World Time

Since Svend founded Andersen Genève, custom watches have been a core part of the business. His sales brochure has long included a leaflet that invites you to design your own watch, quite literally, by offering a page of ruled squares ready for a sketch.

“Ninety per cent of my inspiration comes from people asking if something is possible,” said Svend in The Hands of Time, a book published to mark the 25th anniversary of the AHCI, “I never say no, [instead] I will always think about it.”

As a result, the catalogue of Andersen Genève encompasses such diverse designs that absent the name on the dial, it would be difficult to attribute any of the watches to Svend. Such an approach is unusual in today’s watchmaking landscape where most independent watchmakers want a recognisable, signature design to go with the brand name.

But Svend offers a unique freedom for someone who aspires to inject his own taste into a watch, and working with a client to realise an idea is clearly something he relishes, even after having done it for decades. He still enthuses about the creativity and taste of Italian watch collectors, who were his biggest customers in the 1980s and 1990s. Many took the invitation in the leaflet literally, turning up armed with ideas and sketches, allowing Svend to sit right down and jump into the details of what they wanted.

The Andersen Geneve leaflet that invited you to let your imagination run wild

But when I turned up at Svend’s workshop and sat down with him to discuss the world-time wristwatch, Svend had a peasant at the table in comparison to the Italian aficionados of the 1980s. My everyday watch at the time was an Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Offshore, so I thought anything smaller looked puny.

So the main criteria for the custom world time was a large case, larger than what Svend offered at the time, with a minimum diameter of 42 mm. And the dial had to be made of blue gold with guilloché, something I particularly liked after having seen it on other Andersen Geneve watches.

Having depleted my ideas after putting forward these two specifications, Svend stepped in to help further develop the idea such that it would be sufficient for a watch. He went over to the safe and removed a tray filled with boxes of abandoned and incomplete watch projects, hoping that something would inspire me and further my ideas.

In one box I found a preliminary study for a world-time watch with a regulator-type time display that caught my eye, especially since I knew of no other world-time with this dial arrangement.

Refining the design

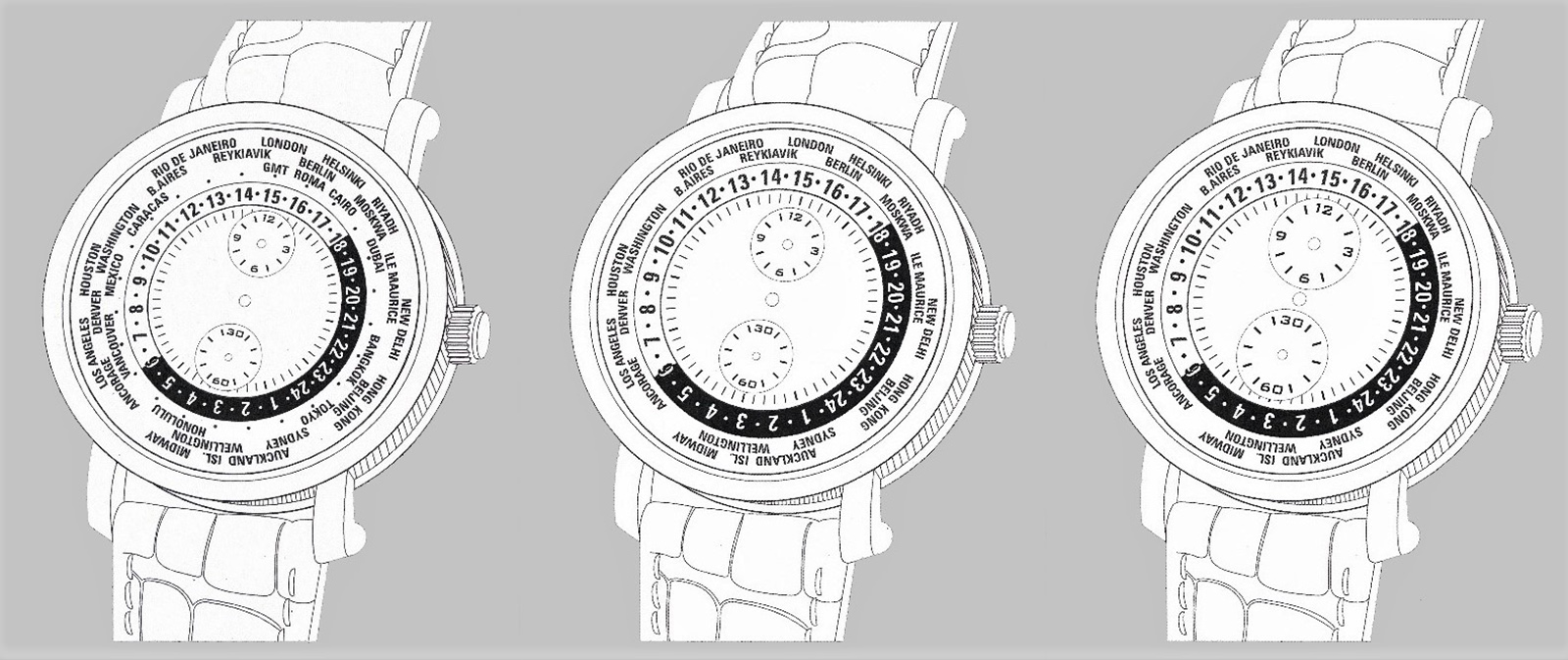

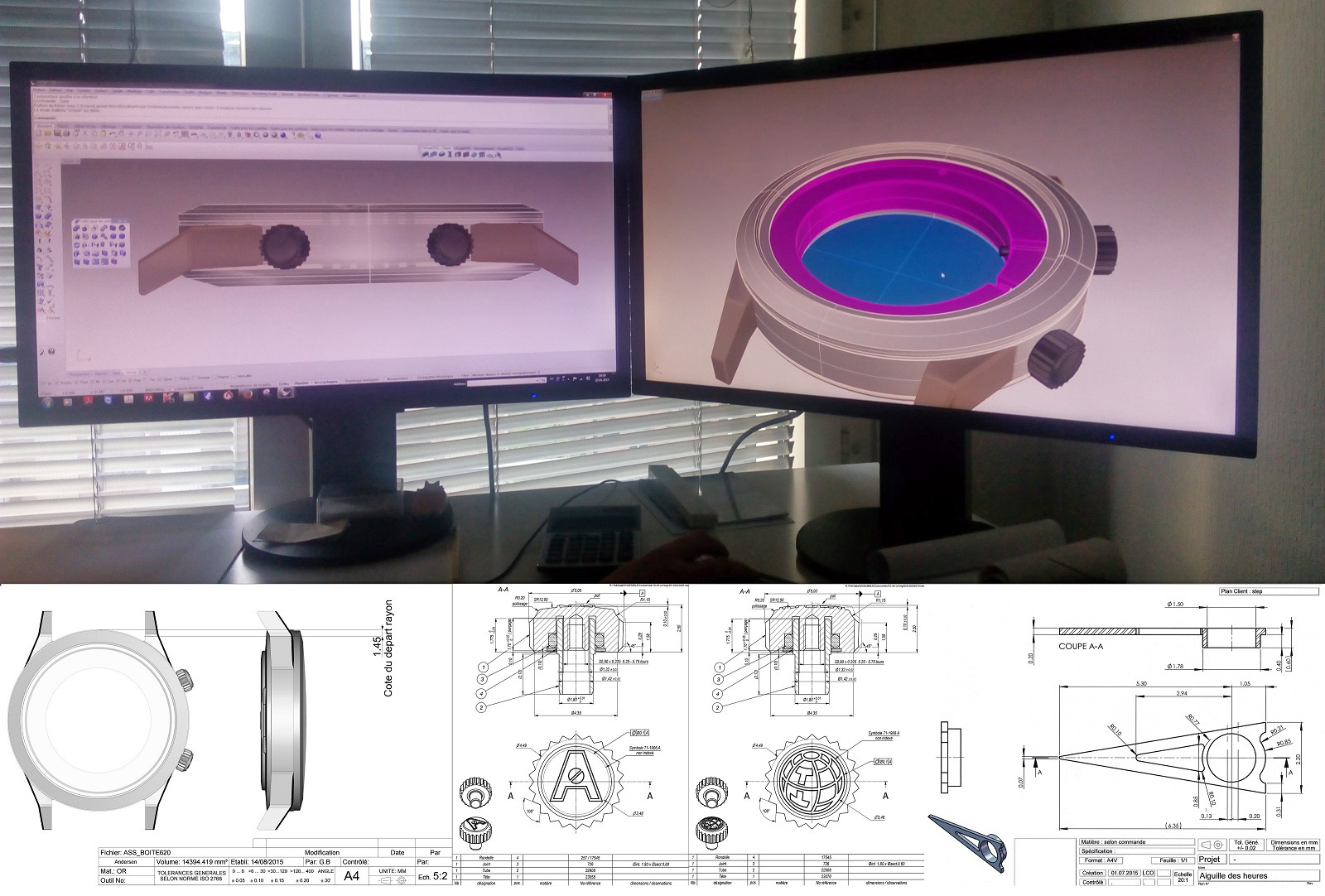

But I had no idea how such an unconventional dial layout would work. Solving that problem was easy: Svend offers monochrome renderings done by his long-time graphic artist, François Martinoli, as part of the customisation process. While basic, the drawings were very helpful in allowing me to play with elements of the dial. In this instance we streamlined the city names from three rows to two, as well as enlarged the sub-dials for hours and seconds, resulting in better proportions.

Should a customer require something more concrete and three-dimensional in order to get a better idea of the design, Svend can also provide photorealistic renderings created by an external designer who specialises in computer-generated imagery of watches. But such specialists typically charge around 10,000 Swiss francs for a set of images, making it entirely out of question for me.

Renderings done by François Martinoli showing the different arrangements of the city names as well as sub-dials of different sizes

A photorealistic rendering of the unique Andersen Tempus Terrae World Time made for Only Watch 2017

Because a Louis Cottier-type world time requires several basic elements, namely the concentric dial rings for the 24-hour scale and reference cities, there was hardly any freedom to change the dial layout substantially, at least in terms of the world time display.

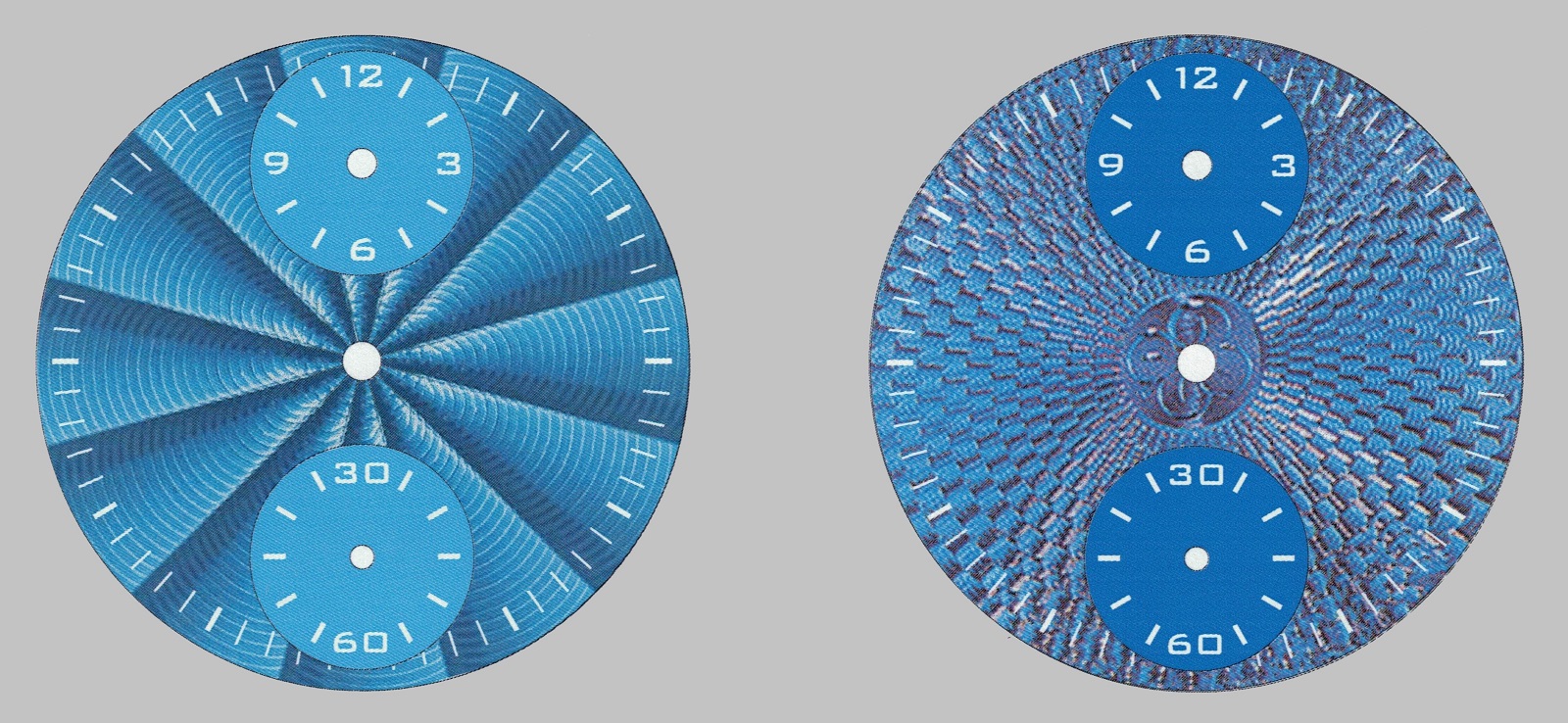

But the advantage of having a modular construction lies in the fact that the base movement is separate from the complications, allowing me to tweak the complications, aside from the world time. That gave me the freedom to rearrange the time indications, and also experiment with the dial decoration, with Svend providing additional illustrations of different guilloché. I decided to go with the pannier, or basket, motif (below right) as I judged the pattern unusual yet versatile.

On the other hand, I was beginning to doubt the regulator-style dial. I feared it would leave the central portion too busy, and not fit in with the rest of the dial. Svend was quick to address my concerns, suggesting a retrograde hour display instead.

The solution that worked for George Daniels also worked for my watch, where the retrograde display improved the proportions of the dial. The appeal of the retrograde hours was confirmed by illustrations Svend provided, which reinforced the necessity of such drawings when configuring a watch.

George Daniels emphasised the importance of proportion in achieving elegance, something he always strove for in his designs. Between 1969 and 1973 he built eight watches with retrograde hours (an example above left), which were all similar but not identical. The dial layout of my bespoke world-time watch also features a retrograde hour scale of 120 degrees. Photo of Daniels – Sotheby’s

Building the module

At this stage, the only thing discussed was design; the implications of the design on the mechanics below had not yet entered the picture.

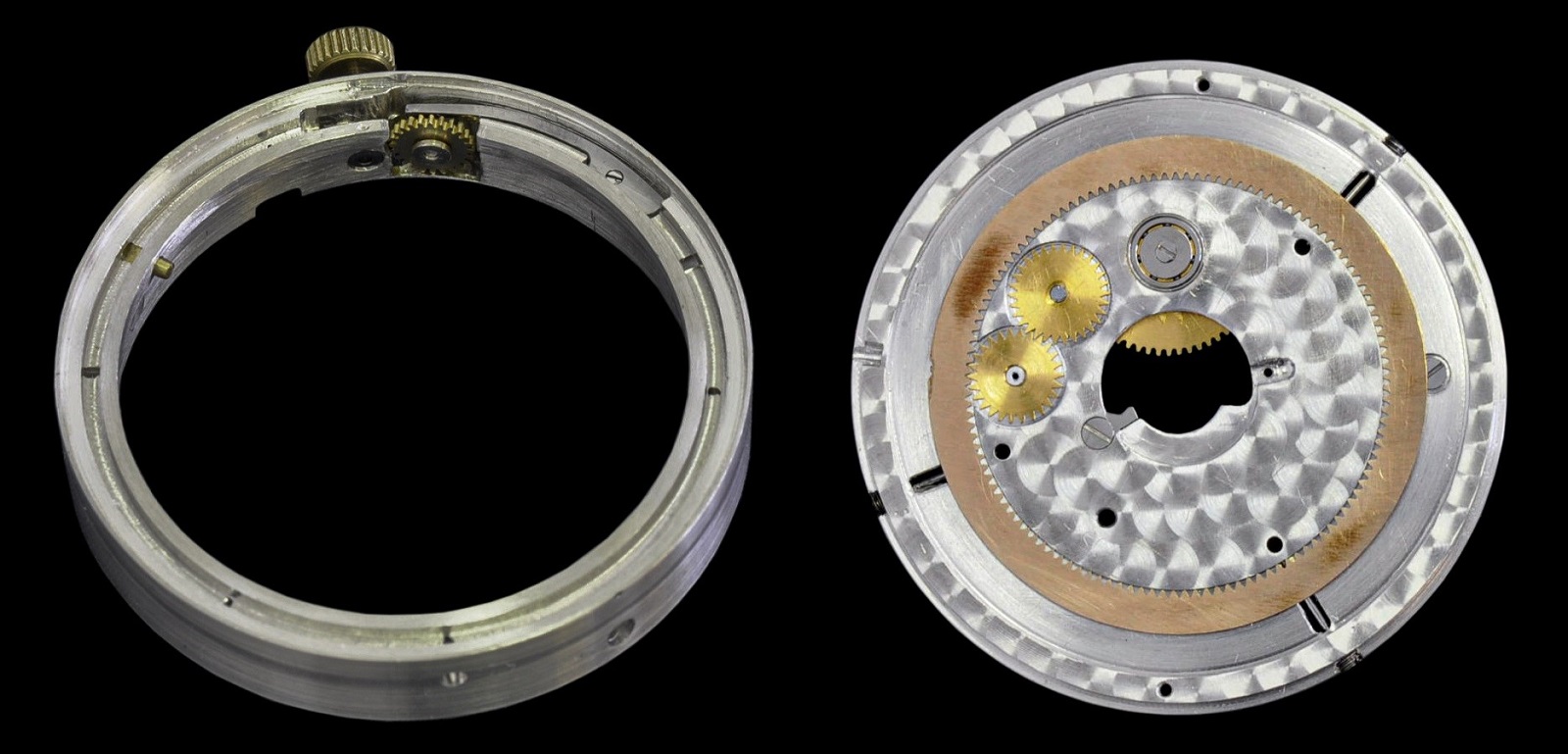

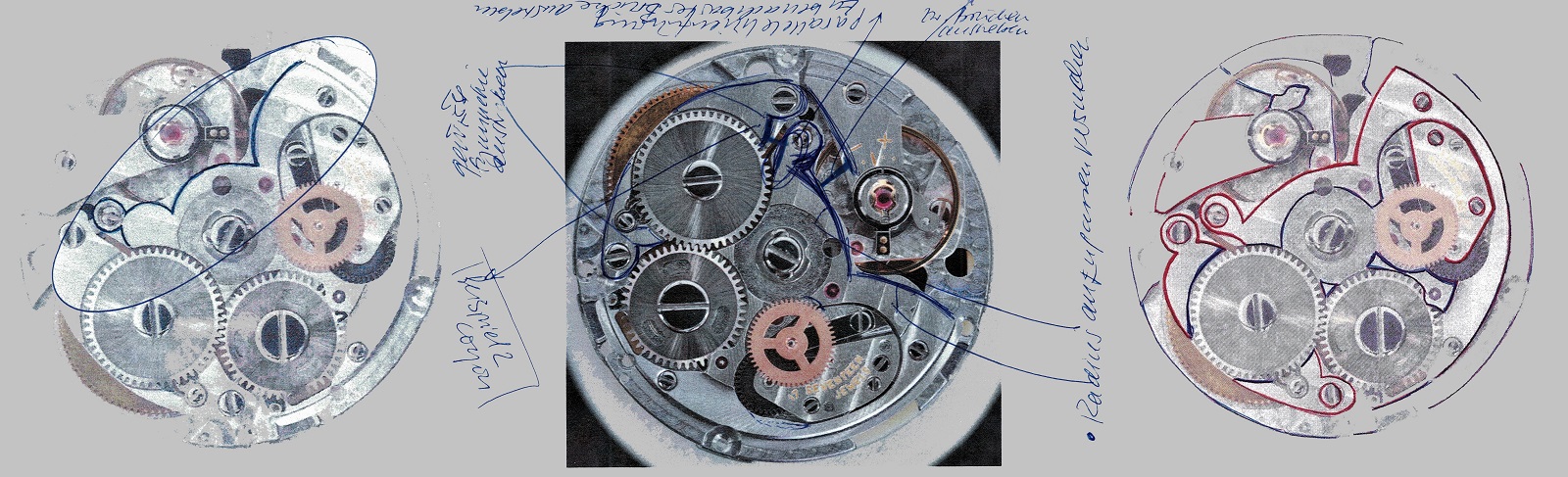

Fortunately, the space in the case was enough to build a module to suit the dial design. In fact, the case also had additional space in between the walls of the case and the base movement, allowing for a module on as well as around the base. So Svend built a two-part module, with the bulk of the world time mechanism in a ring and the rest of the complication mechanism on a plate.

Svend combined the movement-retaining ring and the module by integrating an adjustment mechanism for the time zones into the ring (left), including a spring-loaded device to secure the ring in the right position vis-à-vis the reference cities. The part of the module mounted on the base plate (right) includes the 24-hour display and retrograde hours; in order to minimise its size while making it robust enough to hold the jumping hour hand, a ball bearing is used to hold the pinion of the retrograde hand.

The mechanism for the retrograde hour display in the centre of the module includes a tiny, coiled damper spring to shield the jumping hand from excess shock. The module before the 24-hour and cities rings are installed (left), and after the installation (right).

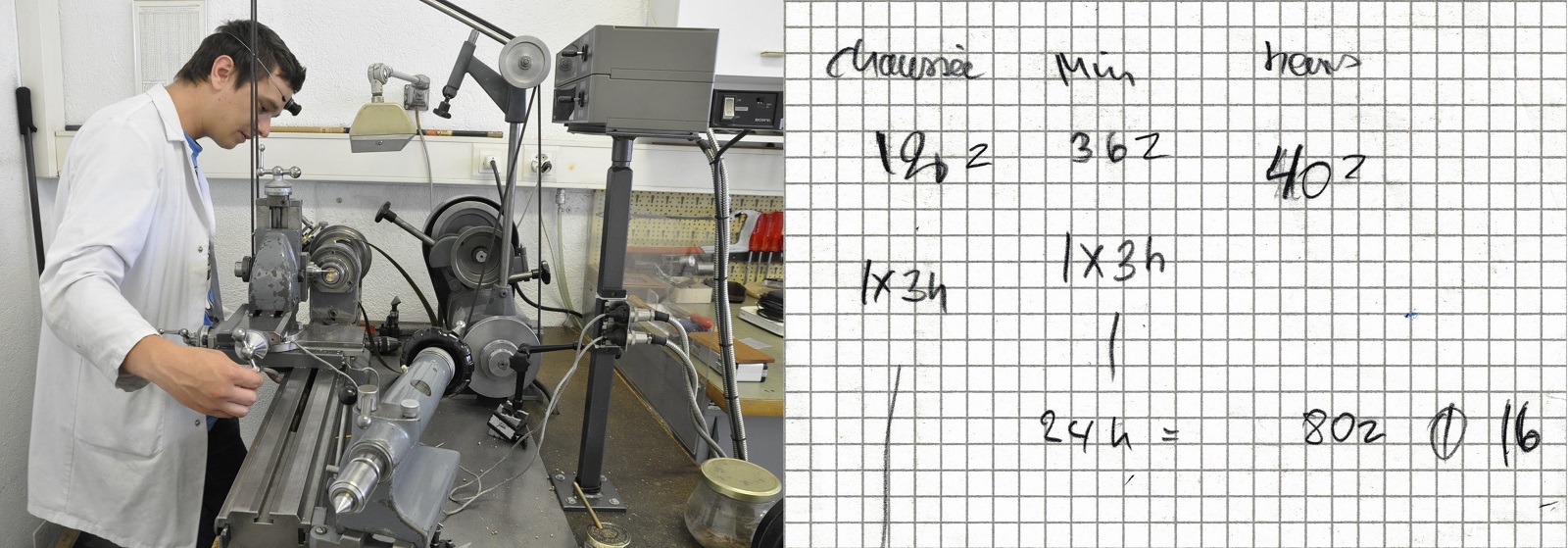

As I noted earlier, the set up of Svend’s workshop allows him to produce parts on an artisanal scale, so only the raw materials for the springs as well as the ball bearings had to be bought from suppliers. The other parts of the module were produced in the workshop, made by hand and refined with a good eye – but without a detailed plan of the mechanism.

The process is surprisingly swift. The experienced watchmakers in Svend’s workshop only need the basic calculations for gears and can then move onto machining the parts. And with raw materials stored in the back room, it takes only a couple of minutes to cut slices from the rod or sheet of metal alloy for the blanks that will be machined into components.

In fact, the artisans at Svend’s workshops are so expert that they have a “feel” for the material – the quantity needed for minimal wastage, the ideal way to work it – a trait, according to Stephen Forsey, that is indispensable for successful micro-mechanical work.

This approach to production and construction is something that Svend’s workshop does on a regular basis. His popular automaton watches, notably the Eros erotic timepieces, are a good example of how it is simply not possible to calculate everything in advance.

Usually the customer for an automaton complication already has a detailed drawing of the scene that will be animated on the watch. Such a scene will often have 10-16 moving parts, each moving at different amplitude and speed, but in a fixed sequence. Since most of the scenes are unique, so are the moving elements that make up the scene. Consequently, all of the mechanisms that drive the moving elements, including pinions, pins ,and levers, are one-off constructions.

As a result, there is a substantial amount of trial and error when fabricating the parts – but the proportion of “error” is small given the tremendous experience of Andersen’s craftsmen. At the same time, the hand-made nature of the parts mean they are often technically straightforward, which helps with reliability as well as repairs in the future, since they can be reproduced by a skilled craftsman.

The lack of detailed technical plans was not a problem for me. Given the hardy nature of the alloys used to build the movement, I am confident there will always be enough of any component to allow for reverse-engineering if something needs replacing, much like the restoration of centuries-old clocks and watches. More practically, minimal planning means saving time and money, which is eminently useful when working to a budget.

Bona fide hand-made

Nowadays even ostensibly “hand-made” watches contain some parts made by automated processes in computer numerical control (CNC) milling machines or automatic bar lathes. This not only ensures absolute interchangeability of parts, but minimises manufacturing time, which the watchmaker can instead devote to hand-finishing.

That said, before CNC machines can do their work, a movement constructor has to create detailed drawings for each part, then translate the drawings into manufacturing directives that can be fed into the machine. The translation is usually done by another specialist using computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) software, and will include technical details like the specific tools required and the ideal machining sequence.

All of that is time-consuming, and consequently expensive, meaning that such industrial production methods are not viable for a one-off watch, especially when the customer wants to keep the cost close to that of a comparable, serially-produced watch. As a result, and somewhat ironically, hand-made parts make more sense when it comes to one-off watches.

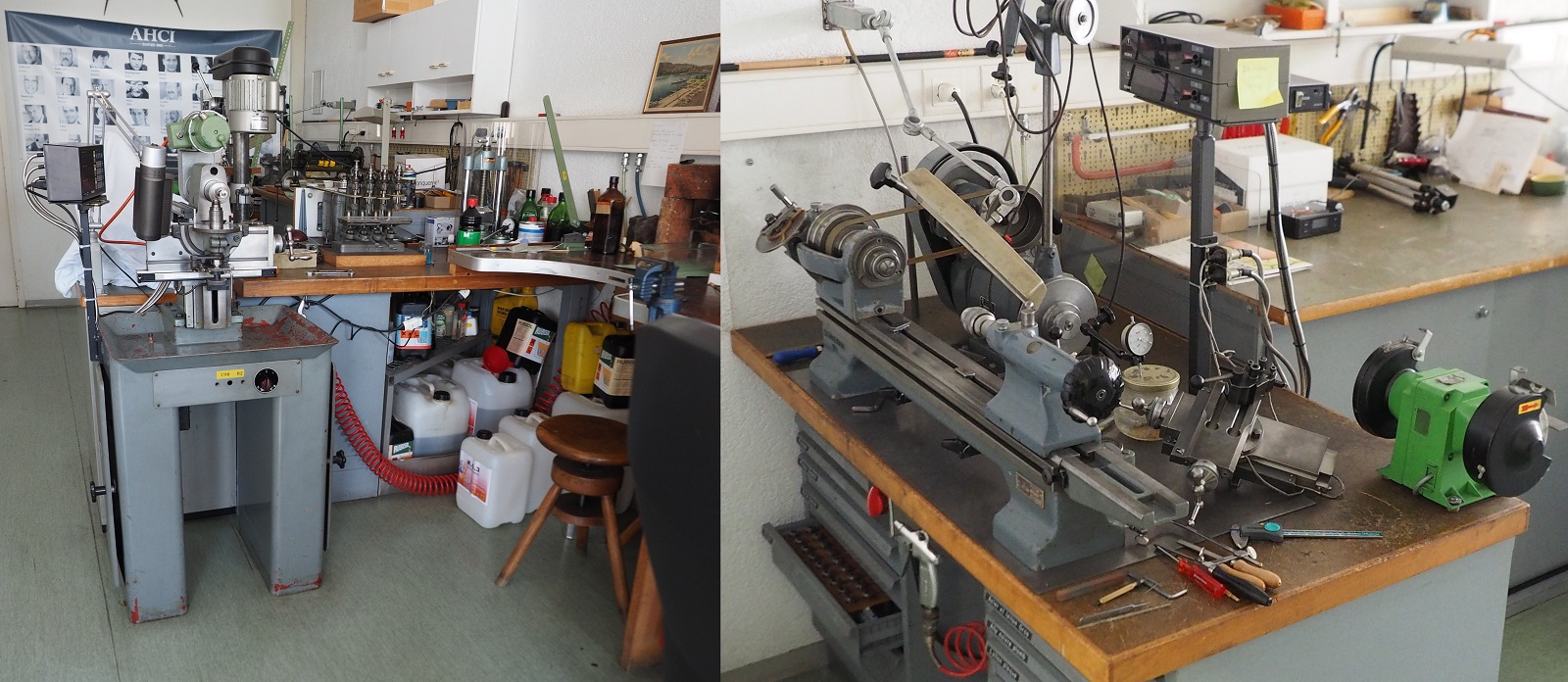

Svend can produce nearly all the parts of a watch in his micro-mechanical machine shop

For movement components that require precision, “hand-made” still requires some degree of mechanical assistance in the form of manually-operated machines, but guided by a skilled operator whose hands replace the computer programming of a CNC mill.

Such skilled operators are increasingly difficult to find, even in the watch industry, where “hand made” is frequently touted as a key element of watchmaking. When Greubel Forsey unveiled the Hand Made 1, the announcement noted that even manually-operated machines can achieve tolerances of up to 2 micrometres – or two-thousandths of a millimetre – but the skills necessary to achieve such precision are no longer taught in watchmaking school.

Svend and his team, on the other hand, have been applying such skills for a long, long time – and have all the tools to do it, some of which are over a century old. His workshop includes a facing lathe, otherwise known as a burin fixe, which is driven by hand with a pulley and handle.

Not just an antique prop for photos, the facing lathe is an anachronistic bit of equipment used only for very specific tasks, and it is not representative of the whole. The machine shop is mostly made up of equipment of 20th-century industrial quality, the very sort required to achieve the precision called for in a watch movement.

The most useful machine for one-off parts production is the universal tool milling machine (left), while gear wheels are produced on the Schaublin lathe (right), a familiar sight in watchmaking workshops

Svend bought most of the machines during the Quartz Crisis of the 1970s when major brands ended mechanical watch production or went into liquidation. But despite the diversity of equipment, most of the work relies on two well-used pieces of kit, the universal-tool milling machine or an ordinary watchmaker’s lathe.

The comprehensive production capability of Svend’s workshop, from the micro-mechanical machine shop to the storeroom of raw materials, means Svend does not have to deal with external suppliers too much, avoiding the accompanying issues of logistics and quality control. As a result, his artisanal vertical integration is cost efficient for both the company and the client, something that is reflected in the price of the watch.

Svend’s workshop can produce more than movement parts – because no suitable hands could be found in the supplier’s catalogue, Svend made his own, first cutting them from a sheet of metal on a milling machine, and then hand-finishing them with bevelling and straight graining.

But Svend’s workshop goes beyond just having a full range of hardware. It is staffed by a strong pool of talent, many being young watchmakers, whom Svend is always happy to advise and enlighten.

As with his production methods, Svend’s method of teaching allows for lots of independence, as well as trial and error. He believes that doing is the best way of learning, so he demonstrates the technique once, and then leaves the watchmaker to do the work himself. Svend doesn’t do step-by-step training or demand repetitive drills.

As a result, only enthusiastic, motivated, and skilled watchmakers survive for long in his workshop, but nothing makes Svend more proud than seeing his youthful colleagues gaining confidence as they work.

At the same time, Svend understands that any watchmaker of substantial talent will eventually want to strike out on their own, meaning that his best students have all come and gone, often onto careers of fame and occasionally, fortune.

Gaël Petermann, who worked for Svend before starting his own brand, shown here producing a gear on the lathe (left), working from rudimentary calculations (right)

As a visiting customer, observing the goings-on at the workshop were fascinating and also reassuring – a watchmaker working calmly at the bench, before suddenly getting up and going over to the lathe, where he produces the part, tempers it over a flame, and then returns to the bench, almost in one unbroken motion.

On a more practical level, Svend’s colleagues are crucial in reducing the time needed to execute bespoke projects. In my own experience, custom or bespoke work can linger for years when done by a single watchmaker. In contrast, my bespoke Andersen world time took only 8 ½ months from confirmation to delivery.

A scene from Svend’s workshop: having turned a pinion on the lathe, the watchmaker now tempers the part over a flame, before fitting it into the movement

The base movement

For all his accomplishments in terms of complications, Svend has never had the ambition to build his own base movement, for two main reasons – flexibility and cost.

The requirements for a base movement vary, depending on what the customer wants. For example, an elegant, simple watch calls for a slim movement, but a highly complicated watch will require a powerful base calibre. As such, an outfit like Andersen Geneve that offers a diversity of timepieces would need not one but several movements.

Even a more specialised brand that requires just one straightforward movement still needs to make a massive investment to get there.

Richard Habring of Austrian independent watchmaker Habring² provided an insight into the extraordinary cost of building an in-house movement during a recent talk at the Horological Society of New York, where he outlined the investment Habring² had to make to develop the A11 movement.

Even though the A11 started with the architecture of the tried-and-tested Valjoux ETA 7750, the development process took some 2,500 hours.

Habring² chose the 7750 for the underpinnings of the A11 so that its existing complication modules, which were all made to fit the 7750, were compatible with the A11. But even then the cost was eye-watering, some €500,000, a number that included the set-up costs for small-scale production of parts at external suppliers.

Given the small scale and custom nature of Svend’s output, the additional costs from amortising such an investment over relatively few watches would result in prohibitively high prices. Simultaneously, Svend also wants to avoid the inevitable teething problems found in newly-created movements, and the first few clients essentially having to beta-test the new calibre.

So Svend always relies on existing movements, especially vintage calibres made in the second half of the 20th century. He is particularly fond of those made by A. Schild (AS), which he likes for their robust, high quality.

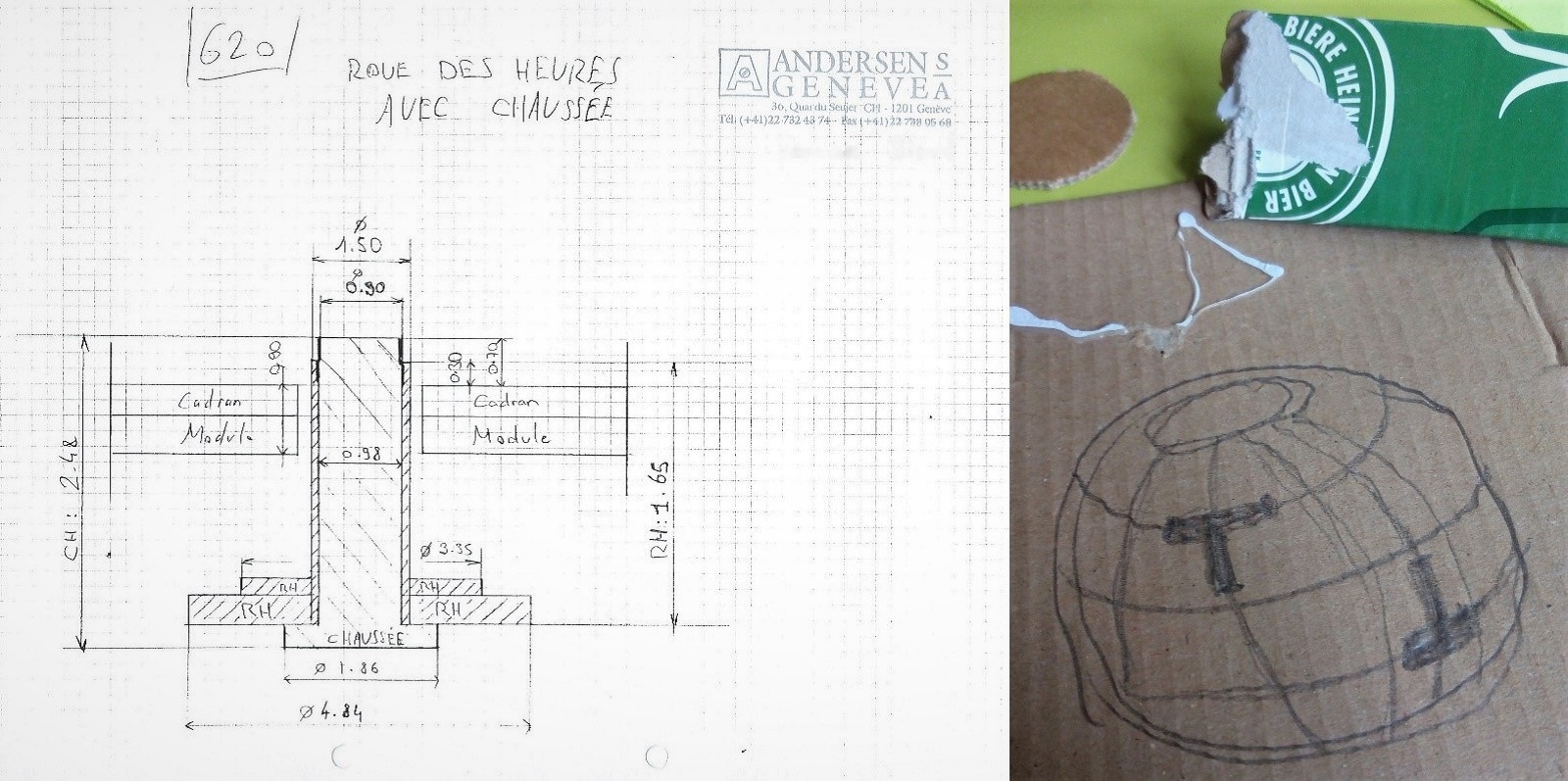

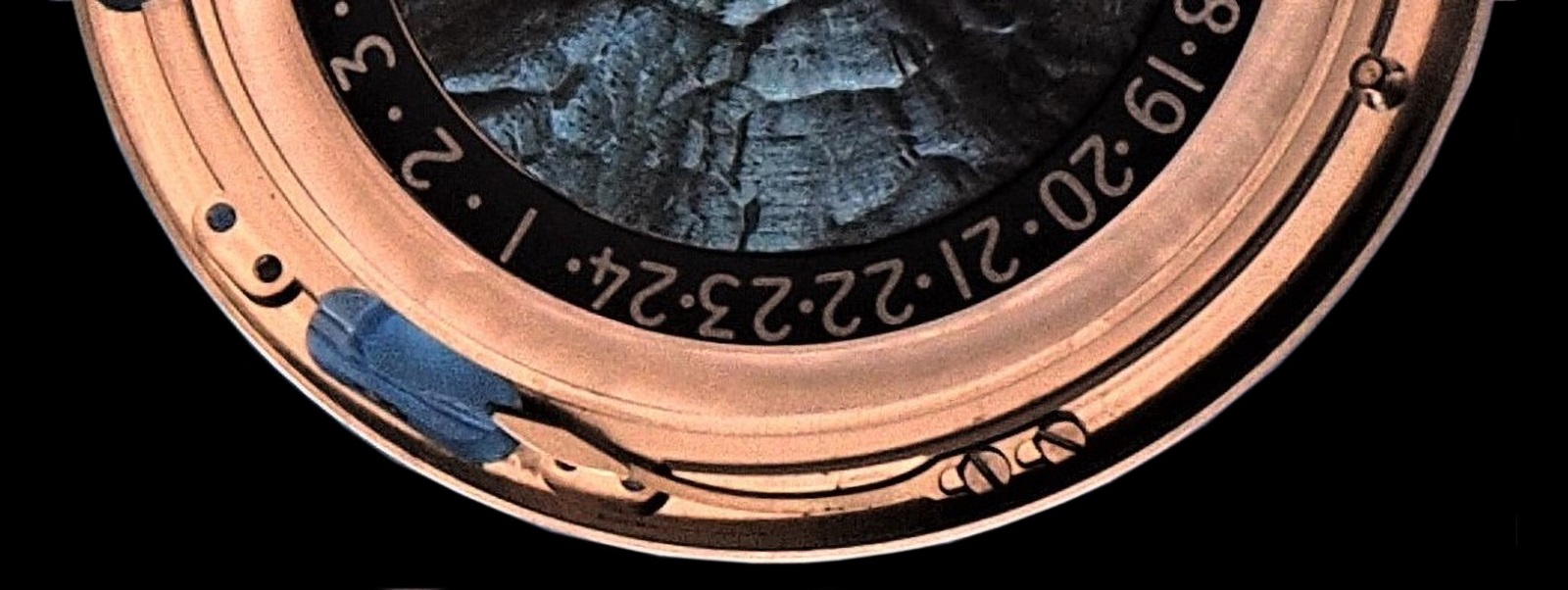

That said, the base movement is a functional and practical choice that depends on the design and functions of the watch. For the bespoke world time, the key factors were the seconds at six and a large diameter so as to maintain a good distance between the central and seconds axes. That led Svend to the AS 1130, a so-called “Wehrmachtskaliber”, or “Wehrmachtswerk”, of 29.33 mm diameter, which also enjoys an ample supply of spare parts.

The AS 1130 was one of several movements by different makers that were built to specifications laid out by the Wehrmacht, or German army, which required robust and reliable movements for its issued watches

Given its military origins, the original AS 1130 had no decoration at all, so it had to be dressed up. To spare me the cost of movement-specific tooling to apply Geneva stripes on the bridges – at least 800 francs – Svend found a specialist in the Jura that still had the vintage tooling for this movement. As for the bevelling of the bridges, it fell to Gaël Petermann. He had recently arrived at Svend’s workshop from A. Lange & Söhne, where he gained substantial experience in applying anglage.

Though I was satisfied with the decoration, had I wanted something different after it was complete, the movement could have been replaced at modest cost – one of the advantages of an easily available calibre.

Decorating the movement is as far as Svend will go in terms of movement aesthetics. Because he only chooses base movements of a minimum technical quality, Svend sees no point in camouflaging the original design with new bridges of his own, a popular technique for facelifting vintage movements. In fact, Svend believes that results in nothing gained except extra cost.

To avoid a case back with an overly-wide rim, Svend fabricated a ring in blue gold to fill up the space between base movement and module; the blue gold ring was also hand-engraved, turning it into a decorative element

The case maker

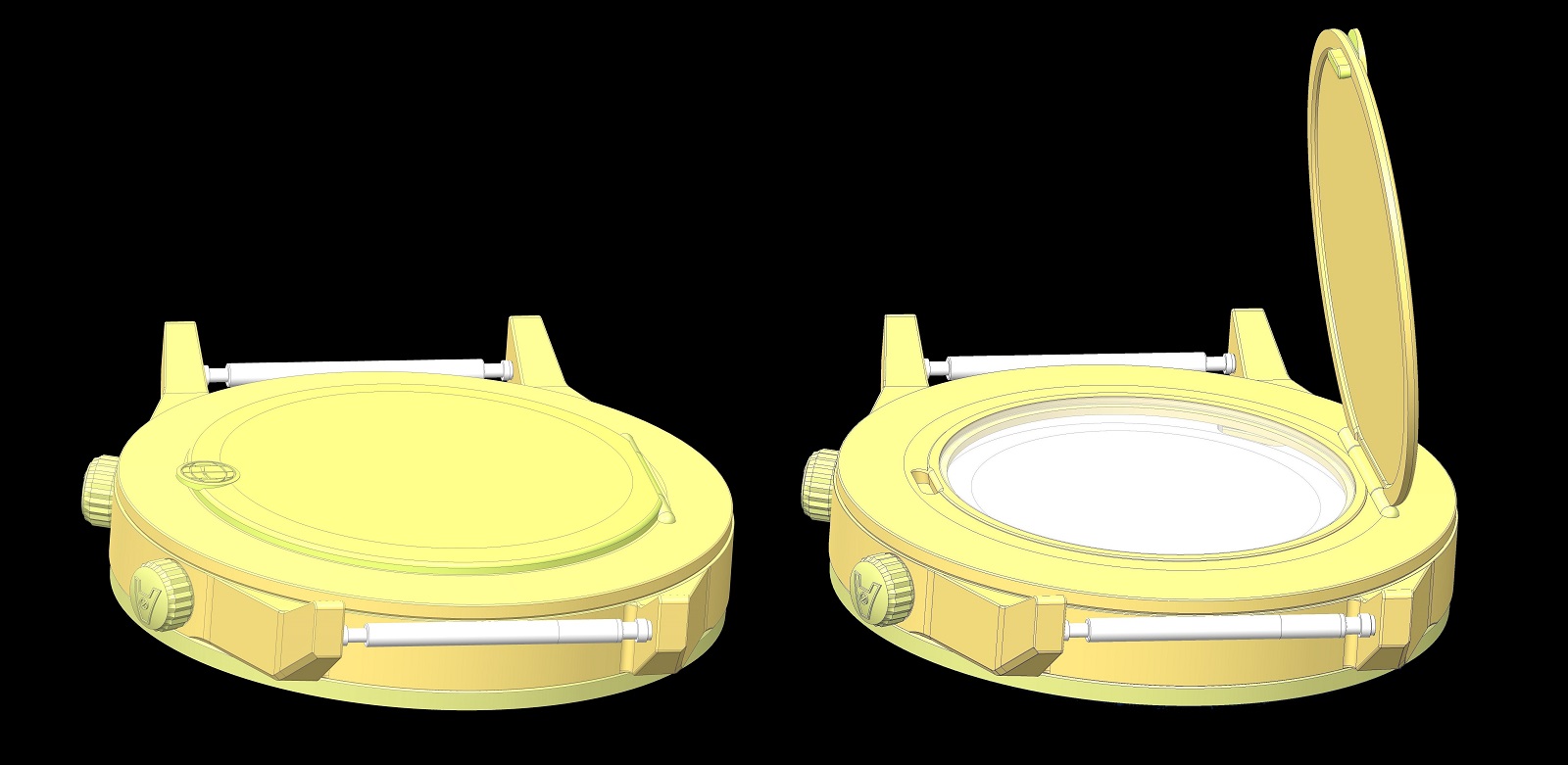

For the bespoke world time, Svend proposed a case design often known as “Empire”, a classical style but one versatile enough to be made taller in order to accommodate a thicker movement.

Amongst the typical elements of an Empire-style case is a fluted case band, which I opted to forgo as I found the fluting old-fashioned. I questioned my decision when I saw the finish case and its wide expanse of polished metal on the sides, but Svend dispelled my doubts by pointing out the case was merely a frame for the visual centrepiece, the guilloché dial in blue gold.

The case was made by Jean-Pierre Scherrer, who more recently also produced the Empire-style case of the Andersen Genève Montre a Tact for Only Watch 2019. He, along with Jean-Pierre Hagmann, has long been the case maker of choice for Svend.

Both are considered amongst the best case makers of their generation, but each approaches the craft in a subtly different manner. Mr Scherrer prefers to work with the lathe, while Mr Hagmann is particularly good with complex and form cases that require soldering to join various parts of the case together.

Like most artisanal case makers, Mr Scherrer doesn’t need many machines. In fact, he has never used a CNC machine, and made most of the case for the world time on a lathe.

The finished but empty case by Mr Scherrer

The finished watch

It is easy, in principle, to acquire a one-off watch, when working with a watchmaker like Andersen Genève. But the ease was mitigated by my tastes and preferences at the time, and how I utilised the technical possibilities offered by Svend.

My inexperience when I began the project led to some silly decisions, including wanting a large case. I also lacked knowledge about material properties as well as the variety of decorative techniques available. Neither I did have the imagination to see the end result in my mind, which would have helped me to explore the possibilities more fully.

An example of where more could have been done is the dial. While the dial centre is guilloche blue gold, the cities ring and day-time half of the 24-hour ring are off-white, an attempt to inject a bit of elegance. But I did not pay much attention to the typography or arrangement of the city names, neglecting to eliminate the spaces in-between certain city names. While the font used for the cities is not the most elegant, Svend likes the simple and bold typography, and appreciates its readability.

It does require experience for a collector to correctly specify a watch from scratch, and even then a positive result requires good advice from the watchmaker. But being sensitive to criticism, watchmakers are often careful with their advice, making it sometimes difficult for the client to learn.

That is why I stress the importance of collaborating with the watchmaker in such projects. When I proposed my ideas for the world time to Svend, they were not orders to be followed without question, but rather the opening salvo in an exchange of ideas where the watchmaker was welcome to give his unvarnished opinion. Only then could I, or any collector, benefit from the watchmaker’s experience.

Despite having developed keener eye for detail since I commissioned the watch six years ago, I still love the Retrograde World Time, not the least because it opened up a new world of bespoke horological adventures. While the price came in under my budget of 50,000 francs, I now realise that extensive personalisation of an existing watch – rather than building something from scratch – might have been the better start.

And so extensive personalisation is exactly what I did with my next world-time watch, where once again I turned to Svend.

Personalised – Andersen Genève Tempus Terrae

Several years ago, a collector from the Middle East commissioned a world time watch of a modern yet elegant design, one that took inspiration from the Patek Philippe ref. 2523 HU of the 1950s, otherwise known as the double-crown world time.

When the watch was finished, the collector allowed Andersen Genève to produce a variant of the watch as a limited edition, which became the Tempus Terrae, a world time watch ready for personalisation.

The Patek Philippe ref. 2523 HU wasn’t a hit in its day, reputedly due to the high price but also the bold and angular design, most notably the lugs, but now the rare watch is worth seven-figures

Andersen Genève presented the Tempus Terrae at Baselworld 2015, with an intriguing detail on the dial: “Moskwa”, which is Russian or Polish for “Moscow”, rather its spelling in English as done for the other cities

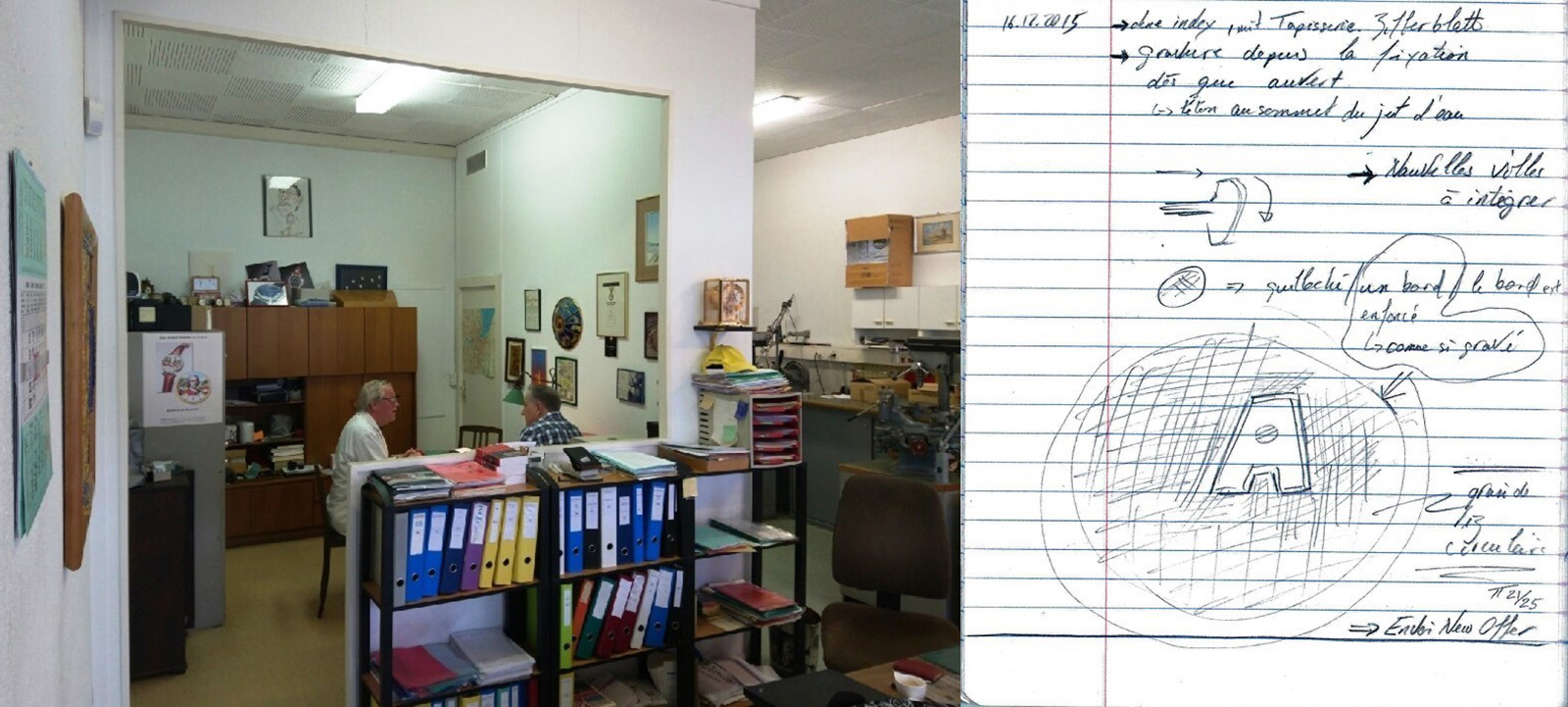

The Tempus Terrae was conceived as template for customers who want a one-off watch but do not want to start from scratch. But the Tempus Terrae still manages to offer significant freedom in personalisation, going well beyond minor cosmetic tweaks. And an intrinsic part of the personalisation process is the discussion with Svend and Pierre-Alexandre Aeschlimann, who took over Andersen Genève in 2015.

My discussions with the two gentlemen were extensive, as I wanted a greater degree of personalisation than most clients. Importantly, Andersen Geneve was extremely reasonable in its charges for all of the extra work.

In most instances, Andersen Geneve added no markup of its own to the bills from external specialist, so I essentially paid Andersen what it paid its supplier. So my substantially-customised Tempus Terrae cost only 16% more than the standard model, which was reasonable and well worth it.

The first discussion with Svend takes the client into the life of the workshop with its easy and informal atmosphere

Designing the personalisation

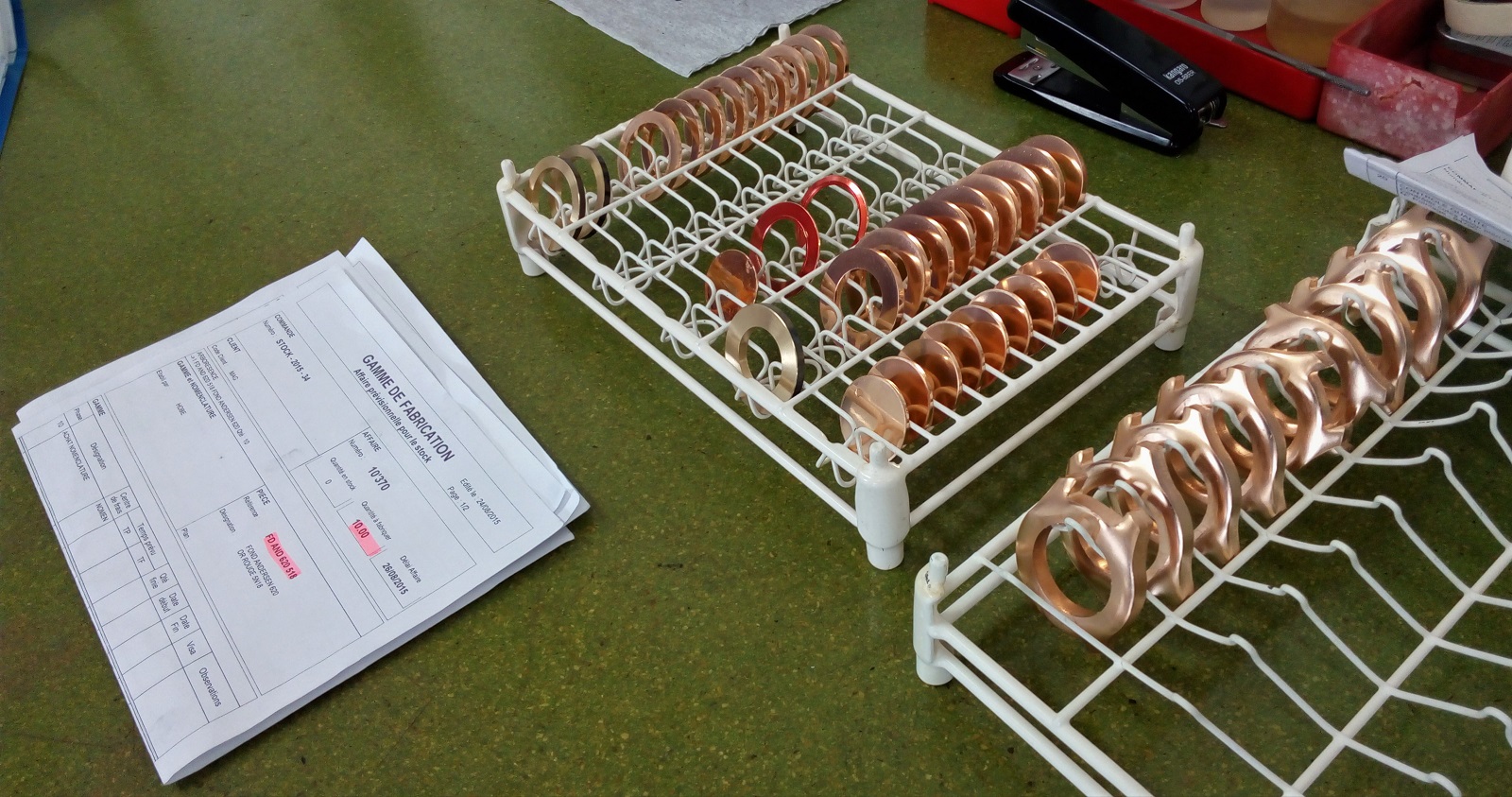

The nature of the Tempus Terrae meant that its design had to incorporate the possibilities and limits of personalisation, especially since many of the components are made by industrial manufacturers, who can produce the quantities necessary for the 75-piece limited edition, a number far larger than Andersen Genève’s typical production runs.

Majority of the personalisation options for the Tempus Terrae are to do with the dial and hands, with only minimal space for manoeuvre in the rest of the watch. The design and construction of the case, however, were done in such a way as to allow for artisanal decoration like gem setting or engraving.

Set with 36 baguette diamonds, the jewelled Tempus Terrae looks more discreet on the wrist than in photos, with the polished gold bezel partially visible through the diamonds, giving the impression of a fluted bezel when seen from a distance

The case, which is milled from a solid block of gold (instead of being cast) is one major element that is fixed in shape and style. Still, I made an attempt to customise it.

Andersen Genève ordinarily offers the choice of yellow, rose, or white gold for the case, but I wanted platinum. The case supplier – a large outfit instead of an artisan like Jean-Pierre Scherrer – insisted a change of material required reprogramming the milling machine and new milling tools, though that opinion was not shared by some other case manufacturers. Consequently, the quote for a platinum case was so high that Pierre-Alexandre didn’t even bother telling me what it cost, and I settled for a white gold case.

Svend and his watchmakers still do the initial technical drawings and design sketches the traditional way, by hand. Technical drawings, like that for the hour wheel arbour (left), are done on graph paper; while designs are done on beer cartons, as with the sketch for the engraving on the crown (right)

The partners making basic parts converted Andersen’s hand-drawn plans into the CAD renderings required for industrial-production – above are the plans for the case and crowns

The case supplier was also insistent that a new set of tools were needed to apply the brushed finish on the case band, a detail I wanted in order to create contrast with the polished top surfaces. Fortunately Svend came to the rescue by hand finishing this part of the case himself, managing to do it without any new, specialised tools.

These limitations in customising the case showed me how a watchmaker sacrifices flexibility when working with certain industrial suppliers, reinforcing the appeal of Svend’s small-scale, artisan production.

The Tempus Terrae cases were produced in batches of 10 at a time, and not the 75 of the entire series at a go

Fortunately, the case was designed to have generous space for engraving, most notably with the hunter case back, a standard feature for the Tempus Terrae. It’s a blank slate perfect for larger-scale customisation on both faces.

Developed by Andersen Genève and the case maker specifically to have an unobtrusive, inset hinge, the hunter back sits relatively flat, in contrast to the sometimes bulky hinged backs found on other watches.

A new attachment was developed for the hinged lid that allows it to be secured from the underside of the case back via two tiny screws in the hinge, making it easier to remove the lid for engraving work, which avoids the risk of damaging the soft gold parts or delicate hinge pins. Diagram – Andersen Genève

The thinness of the hinged cover is obvious in the metal

I chose to have the back engraved on the inside and engine turned on the outside. The guilloche on the outer face was the more straightforward of the work, and cost 1,500 francs.

The choice of guilloche pattern for the outer back was grains de riz circulaire, or “circular grains of rice”, but I also wanted the Andersen “A” emblem integrated into the centre of the engine turning. I took it upon myself to create the mockup for combination, using a pair of scissors and glue to put together an approximation of what I wanted.

Because I wanted several small details done exactly right, including a groove at an exact position to enclose the guilloche, I played it safe and sent Andersen Geneve my home-made cut-and-paste specifications

But despite the seemingly simple task of engraving an “A” and then engine-turning the rest of the back, it turned out to be a challenging process.

The challenge began with Kees Engelbarts, who started the work by engraving the “A” in the centre. He did the job perfectly, but did not consult with the guilloché workshop on the specifics of the transition between the engraved letter and the engine turning. And then the guillocheur got another surprise with the slightly-convex shape of the back, usually an absolute no-go in guillochage, which requires a flat workpiece.

But fortunately the talented artisans managed to solve the problem together. In such situations the customer is always better off when the craftsmen involved are talented and have a friendly relationship, which usually makes the impossible possible.

Integrating the hand-engraved “A” into the guilloche was particularly tricky; the guilloché also creates an intriguing optical illusion of a sunken case back

Engraving the inner face

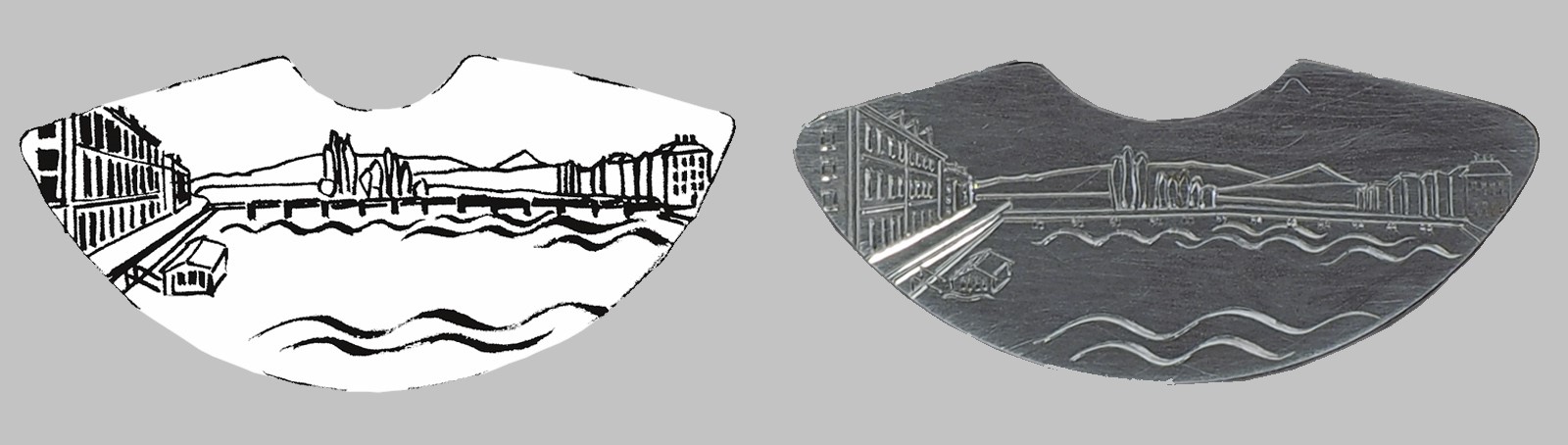

As it turned out, the guilloche on the outer side of the case back was the simpler of the two. Wanting something that could be discreetly admired, I opted for an engraving on the inside of the hunter back.

The process of specifying the engraving taught me pictorial engravings can be a source of frustration for watchmaker and customer – what one imagines the other might conceive of entirely differently, and then the engraver might be thinking of something else altogether.

I asked for an abstract engraving on the inside back, something depicting a typical view of the city along with its quintessential symbols. The broad strokes were easy to pin down: Lake Geneva with the Jet d’eau, the city’s coat of arms with its eagle and key, and the mountain range just beyond the city.

Svend suggested Olivier Vaucher, a renowned Geneva workshop that mostly does work for big watch brands. The initial proposal from the workshop of Olivier Vaucher was unconvincing. It was overly detailed, conceived to be done in the bank note-style of engraving , and a poor match for the streamlined design of the watch to my eye.

An idea can be interpreted completely differently: François Martinoli delivered the abstract motif I wanted (right), while the earlier proposal from Olivier Vaucher (left) was too dense

Established in 1978, Olivier Vaucher offers 17 traditional techniques for the decoration of watches and jewellery. Photos – Olivier Vaucher

So it was left to Svend’s graphic designer François Martinoli, who managed to transform the dense drawing into something bold and abstract. He even added in a few extras, incorporating Saint Pierre Cathedral as well as the Palais des Nations with its sculpture park.

The engraving cost 1,800 francs, inclusive of the drawings and sketches. But the subtle charm it bestows on the watch made it money well spent.

A detail I wanted right was the horizontal alignment of the engraving – it had to be parallel to the plane of the watch, so that the engraving could be admired with the watch laid face down

The differing interpretations of my idea for the engraving illustrates one of the hurdles when the watchmaker works with a third-party specialist for decoration, particularly when the specialist is a company instead of a one-man operation.

The customer has no direct line to the artisan actually doing the work, and layers of bureaucracy make it difficult even for the watchmaker to communicate with the artisan. As a result, an exact drawing for the decoration is indispensable. The engraver will first use the drawing to do a laser etching that will serve as a guide, and then hand-engrave over the etching to fill in the detail and definition.

The back opens to reveal a rotor finished to match the dial

Decorating the dial

An element on a world-time watch ready for customisation is the cities ring. On the Tempus Terrae, the colours of the city names can be changed at no charge, but it costs about 1,200 francs extra for the cities to be printed in a different font, or if the city names are changed.

But the ability to make changes doesn’t mean changes are ideal. It is easy to underestimate the magnitude of a change that appears small on a mockup, but looks disproportionately large on an actual dial.

I learnt that when I asked for the usual 24 cities I have on all my world-time watches, including the Argentinian capital spelled out in full, not being keen on the abbreviated “B. Aires” found on most watches. But the result was a bit of a mess as the full name meant several cities bunched together on that part of the world time ring.

Buenos Aires took up more space than envisaged

To accommodate further customisation, the blue gold centre of the dial has been kept clean, with no logo; the brand’s emblem is instead on the cities ring, along with the use of hand shaped like an elongated “A”.

Andersen Geneve has several standard options for that, including two guilloché patterns, Tapisserie or Scale, though the customer can go beyond the usual, with a different dial material or guilloché for instance. I chose the Tapisserie guilloche, because its more pronounced pattern better matched the design of the case, while also introducing softer, irregular lines to contrast the otherwise taut lines on the watch. But the rest of the dial, including the hands, I largely kept as standard.

The two guilloche dials offered. Photo – Andersen Genève

Off the menu

Conceived to be a slim watch, the Tempus Terrae has a case diameter of 39 mm and a height of only 9 mm, including the hunter case back, so there is no room within the case to add more complications. Still, I insisted on an additional mechanism that clicks the cities ring into place when adjusting time zones, because the standard version of the movement uses a freely-rotating cities ring that felt imprecise to me.

In his usual ingenious way, Svend found space in between the world-time module and case walls that was just enough to accommodate a spring. Featuring a lozenge-shaped tip, the spring tensions the toothed wheel of the cities ring to create the clicking rotation. Svend made this spring by hand, relying on trial and error for the perfect fit, resulting in a click that functions without creating wear on the rest of the movement.

Few watchmakers will create an additional, unplanned mechanism to satisfy a customer’s demand

A bit more of my persuasive power was required when asking for customised movement decoration. Never too keen on finishing movement parts purely for decorative purposes, Svend was happy with the standard movement finish, namely Geneva stripes on the bridges, perlage on the base plate, graining on the wheels, and a blue gold rotor with guilloché. I, on the other hand, believed the AS 1876 base movement could be further refined.

At that point in time, Svend had no one in the workshop with experience to do the decoration I wanted, so I suggested Nathalie Jean-Louis, a decoration specialist in Le Brenets. During a visit to her workshop with Pierre-Alexandre, the two of us realised quickly that she also does anglage for Greubel Forsey.

The standard decoration of the Tempus Terrae movement

Anglage specialist Nathalie Jean-Louis at work. Photo – Décoration Horlogère Nathalie Jean-Louis

Despite her skills, conveying exactly what I wanted was a challenge. Highly specialised craftspeople like Ms Jean-Louis usually work to detailed specifications provided by manufacturers. It was difficult for me as layman to provide comparably detailed instructions, so it took a few attempts for me to get my ideas across.

The initial, sharply-cut bridge shapes Ms Jean-Louis proposed (left) were not to my taste, so I tried my hand at a sketch showing a “flowing” outline (centre). She then refined the idea and created a drawing (right) that I gave to Svend for approval

Another challenge was the base movement itself, which had small and thin bridges that were never designed to accommodate fine finishing. Svend was concerned about the components getting even thinner and deforming.

Because of the extensive decoration I wanted, Svend had to provide a fresh, undecorated movement, instead of one from his existing stock of AS 1876 movements that were already finished. That would give Ms Jean-Louis more room to work.

I asked Ms Jean-Louis to do several things, while keeping in mind the slim parts: a fine frosting, or sablage, of the bridges and base plate; reshaping the outlines of bridges for more elegant shapes; discreet bevelling and polishing of the bridge edges; and all visible wheels to be circular grained.

The extensive decoration of the movement cost a little under 1,600 francs, which I judged to be well justified. I am happy with the result, which has a subdued elegance created by the details and silvery rhodium finish.

My nitpicking with the movement went beyond the finishing to the rotor, which is ordinarily finished to match the dial. While I liked colour and decoration of the rotor, its shape lacked a substantive feel, looking instead like it was stamped from a thin sheet of metal.

My initial idea was anglage for the rotor, which was not possible due to the blue gold alloy used, so I suggested an engraved insert instead.

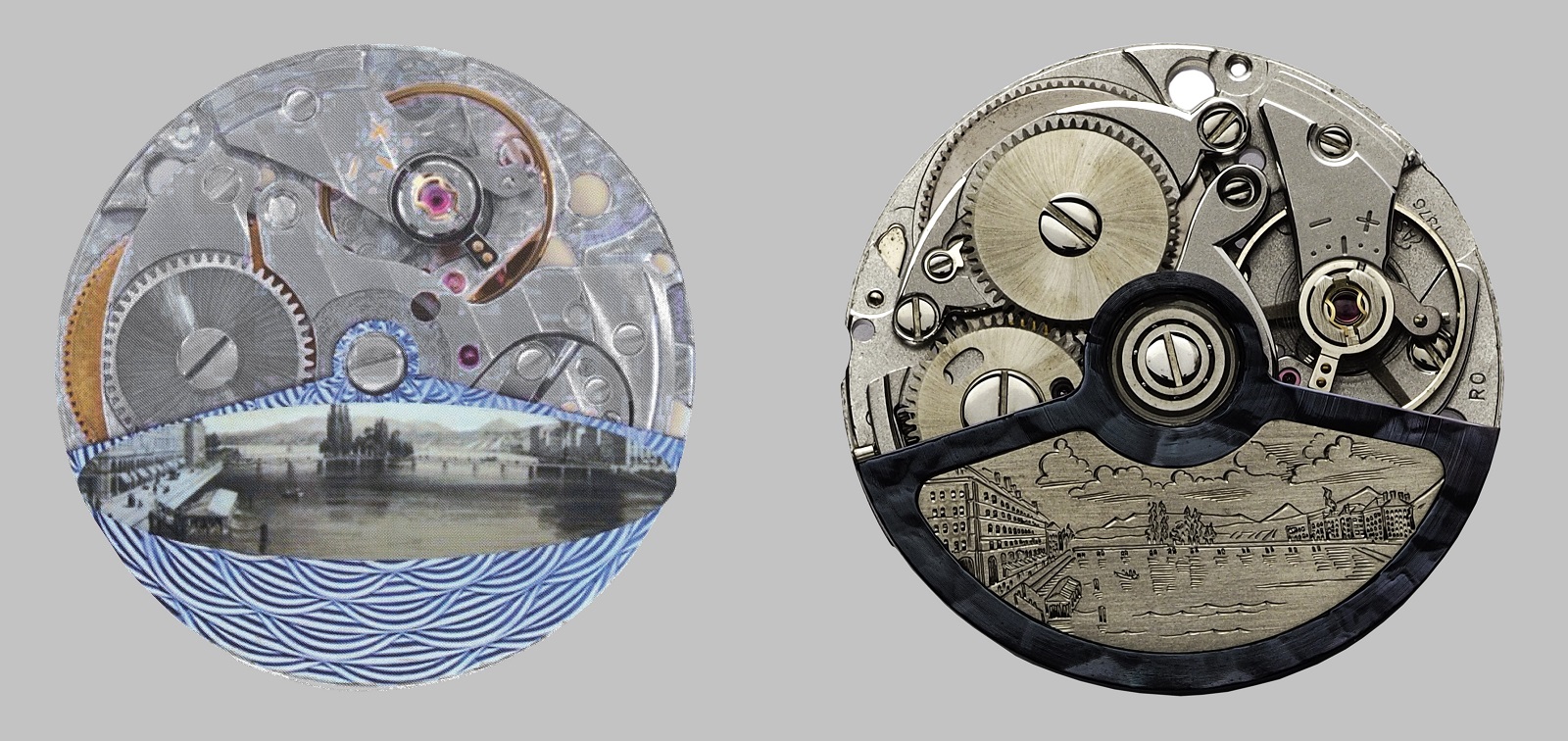

As is often the case for engravings, the inspiration was a landscape on a print I found that depicted a view of Lake Geneva with the mountains in the background, as seen from the bank of the Rhone River – the very same bank where the Andersen Genève workshop is located in fact. The print could not be reproduced exactly as an engraving, needing artistic adjustment to fit the rotor, and Kees Engelbarts was the man for the job.

An engraver by profession, Kees also makes watches under his own name, which gives him a better ability to judge how engraving can fit into a watch, allowing him to share useful opinions with customers, instead of just engraving whatever proposals he receives

Artwork or photos used as a reference must be refined to create a successful engraving, including accounting for the narrower range of expression with engraving, which has no colours

With the print I supplied, Kees created a beautiful engraving on a white gold insert (above right). Unfortunately, nobody had thought of giving him the hinged back as a reference to ensure that the two engravings were done in a similar style. Kee’s first engraving was detailed, and ironically more like the initial drawing of the case back engraving I had rejected.

While I wanted to keep the first version of Kees’ work, I still needed a more abstract engraving for the watch. Once again, I turned to Svend’s graphic designer, and once again I was unable to articulate exactly what I wanted. After two proposals that were not quite right, I gave up and arranged a meeting with Kees, hoping it would bring better results – which it did.

But that wasn’t quite the end of it. After Kees’ simpler, second engraving had been installed, Svend declared it sacrilege to have used the plainer insert instead of the more detailed initial version.

Graphic designer François Martinoli successfully created the drawing for the engraving of the hinged back, but applying the same formula to the rotor inlay did not result in similarly success as I was not happy with the degree of abstraction, which did not take into account the limits of engraving. This illustrates the challenge to the designer, who sometimes has to consider the techniques of a different craft, like how an engraver cannot create dark areas with colour.

Kees sketched a rough outline with pencil on paper (left), which was then used to transfer the outline to the metal inlay for engraving. I liked the simplified, abstract lines of this, but compared to the engraving on the case back, the lines are less bold, something that’s unavoidable without first laser etching the outline given the small size of the part.

Decorative techniques were applied to an industrially-produced movement not designed for hand finishing, but the process was a success. Though the thinner parts of the movement do not showcase anglage and polishing prominently, the finish does nevertheless create a kind of sparkle.

Doing it differently

I was satisfied with the finished Tempus Terrae, but I still pondered various details long after it was delivered. For instance, I wondered about the lack of a border around the blue gold centre of the dial.

Due to the uneven surface created by the Tapisserie guilloche, applied hour markers were not feasible. Other customers opted instead for printed markers of small triangles or squares, but I was unconvinced. But then I saw an example with a railroad minute track combined with the same guilloche found on my watch – and I knew what I had to do.

Svend had to dismantle the watch one more time in order to install the new dial, but that is an advantage of patronising accommodating independents – I can always go back for changes and nobody complains too loudly.

With this post-delivery modification, Svend once against demonstrated the integrity in how he conducts business. With the watch paid for and complete, he could have charged substantially more to add the minute track, and I would have had no choice. And that could have been justified, since the watch had to be disassembled for the dial to be printed. But Svend only charged me 270 francs.

The dial with the addition of the railway minute track

At arm’s length the minute track creates a transition from the dial centre to its busy periphery; but under magnification the difficulty of precise printing on the uneven guilloché surface becomes evident.

Down the rabbit hole

Though customising an existing model might be akin to learning painting with colouring books, having a template allows the client to have an approximation of the outcome. Personalising the details can still make a huge difference to the watch, even though the tweaks are being made to a known design.

The Tempus Terrae shows how “personalisation” can take on a different meaning, even within the offerings of a single independent watchmaker. And it also demonstrates where the client can add the most value to the process, both in terms of his own experience and the finished product.

Though certain aspects of the Tempus Terrae are already fixed, the options for decoration allow a client to get in touch with artisans, a key aspect of the process that’s very close to the experience of a bespoke commission. Customising the decoration is also the most sensible route for an amateur, since it is where the client with less experience can give the most useful input.

And that is enough for most. The imagination and stamina needed to work through simple personalisation, like that for a Tempus Terrae, is already more than what most enthusiasts can muster. For that reason, I can see why Roger Smith has removed the bespoke watch option from his site.

The Retrograde World Time. Photo – Justin Hast

But for others, that is not enough. Getting a taste of personalisation will then lead down the road of bespoke watchmaking.

An accommodating independent watchmaker like Andersen Genève is ideal for such a project. But its openness to a client’s wishes also shifts some of the responsibility for the outcome to the client, so it is more important the client knows what he, or she, is doing.

Another one-off world-time watch created by Svend shows what is possible when the customer has a flair for style and proportions. This elegant chronograph with perpetual calendar and world time resulted from the same brief I had given to Svend for the Retrograde World Time, but the client had professional experience in the fashion and watch industry.

The Frédéric Piguet cal. 1185 used as the base movement didn’t allow for the standard Andersen world-time module, so the world-time mechanism had to be integrated; the unusual hinged lugs were designed for a better fit on the owner’s slender wrist.

My own apprenticeship in bespoke watches is not yet finished. I am still toying with the idea of designing my own watch case, something that I have not seen in the market.

Because no existing case can be used as a starting point, hiring a designer is obviously necessary to translate my idea into a technical drawing that can be produced.

Even Vianney Halter, whom most will attest possesses a vivid imagination, said so in an interview. “I work with designers,” he explained, “This is because I know that I am not able to translate my ideas into shapes and drawings. Even if I tried, the result would not be what I have in my mind.”

That will come at substantial cost. Hiring a professional for the watch case adds at least 18,000 francs to the bill. And doing that does not automatically solve the problem of communicating the idea well. Once again, I would have to overcome the difficulties in making my ideas understandable to the designer.

But hiring a designer is an extreme level of customisation that few aspire to. Already basic personalisation of an existing model with labour-intensive, artisanal decoration is a costly exercise. Though Svend included a good part of his work relating to the personalisation in the base price, my custom Tempus Terrae still cost about a fifth more than the standard model.

Given the challenges and cost of bespoke or custom watches, it is prudent to commission such watches only when you have strong personal conviction in your own ideas, or are prepared to accept honest advice from the watchmaker in order to get it right on the first try.

Back to top.