In-Depth: F.P. Journe Tourbillon Souverain Vertical

The final evolution of the his original invention.

The very first wristwatch François-Paul Journe created was the Tourbillon Remontoir d’Egalité – three prototypes were made in 1993 and he retained the very first example. Arguably the most famous F.P. Journe wristwatch alongside the Résonance, the tourbillon has since evolved into the Tourbillon Souverain Vertical, which is likely the final version of the watchmaker’s take on Abraham-Louis Breguet’s invention.

Conceived for chronometric utility as a wristwatch, the Tourbillon Vertical, or “TV” for short, is the latest iteration of Mr Journe’s interpretation of A.-L. Breguet’s invention. It was launched in 2019 for the 20th anniversary of the Tourbillon Remontoir d’Egalite.

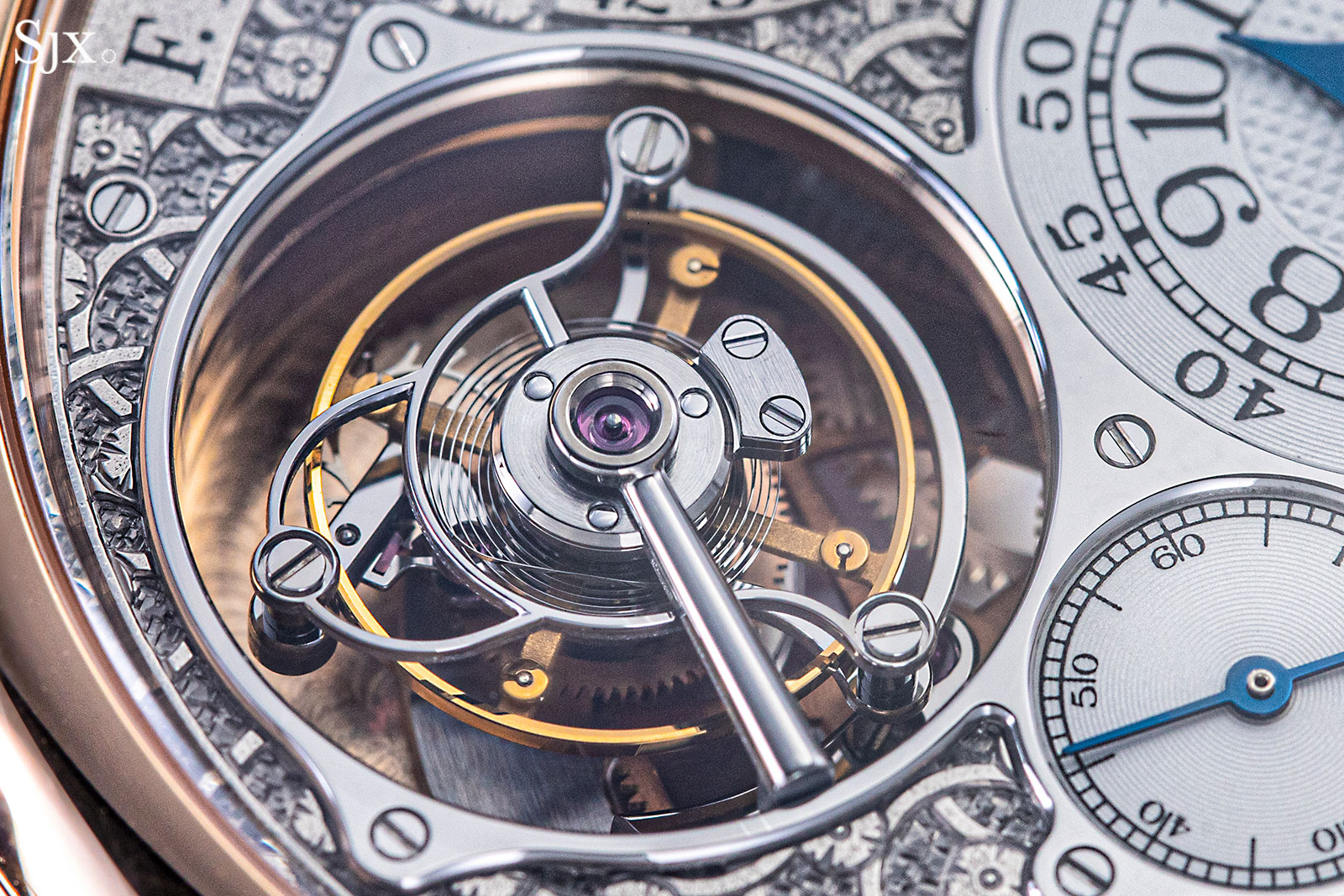

The vertical tourbillon sits in a countersink with mirror-polished sides

The Tourbillon Vertical retains the signature double feature of the original F.P. Journe tourbillon, namely a tourbillon regulator and a remontoir d’egalite, or constant force device. But while the prototype and all subsequent iterations of the F.P. Journe tourbillon had a flat tourbillon on the same plane as the movement, the Tourbillon Vertical is self-descriptive. Its tourbillon sits perpendicular to the movement, with both the carriage and balance wheel standing at a 90° angle to the plane of the dial.

In sophistication, finish, materials, and even size, the Tourbillon Vertical is far removed from the 1993 prototypes. Yet it is quintessential F.P. Journe in its elegant, concise technical approach while also incorporating clever, intuitive details like the high-speed rotation.

Moreover, the Tourbillon Vertical harks back to the original F.P. Journe tourbillon of 1993 in substance and form. At heart, it is still a tourbillon with constant-force device, just like the original, but also in terms of style. In fact, with its exposed, solid-gold base plate and no full dial, the Tourbillon Vertical is almost a literal homage to the seminal original.

One of the three prototypes made by Francois-Paul Journe in 1993

Reorienting the tourbillon

The classic tourbillon invented by A.-L.Breguet is straightforward. The axis of rotation of the tourbillon carriage coincides with the axis of the balance wheel, with the regulator assembly sitting parallel to the plane of the movement. In the past when the primary timekeepers were clocks and pocket watches, this planar arrangement made sense, since pocket watches were primarily worn vertically in waistcoats or other garments, while clocks stood upright.

Because of the vertical orientation, gravity was exerted on the movement in one direction — downwards and perpendicular to the rotational axis of the tourbillon. During the rotation, every part of the balance and hairspring assembly would be equally and progressively subjected to gravitational pull, negating any polar or equilibrium defects. (Interestingly, it has been theorised that Breguet also invented the tourbillon to ensure even distribution of lubrication within the escapement and balance but that’s another topic altogether.)

The third tourbillon ever made by Breguet, watch no. 1176 was sold in 1809, a few years after the invention was patented. Image – Christie’s

The fundamental construction of the tourbillon remained the same over the following two centuries, since the concept remained logical for pocket watches, which were the main form of portable timekeeper until the early 20th century. While esteemed makers such as Alfred Helwig, James Pellaton, and Bahne Bonnikesen tweaked and refined the original concept, the tourbillon’s orientation was undisputed.

Eventually, however, tourbillon regulators started to make their way into wristwatches, experimentally in the 1940s at Omega and then in serial production in the late 1980s with various watch brands. When worn on the wrist, a watch is subject to ever-changing positions, which the tourbillon cannot cover effectively. As such, watchmakers begun questioning the classic tourbillon orientation.

A Patek Philippe tourbillon pocket watch made in 1929 with the tourbillon fundamentally unchanged from Breguet’s invention two centuries earlier

Depending on the wearer’s activity, a wristwatch can undergo any number of positions over a day. But with the norms of modern life, there are some positions in which a wristwatch tends to spend more time in. For example, a wristwatch is in a vertical, crown-down position when the wearer is standing or walking, somewhat equivalent to the vertical position of pocket watches.

While the wearer sits at a table or desk, working a keyboard or merely resting their hands, the watch is in an intermediate orientation between the vertical and horizontal. A wristwatch is in very similar orientation during driving.

And when taken off over night (or stored over longer periods), a wristwatch is usually left resting on its flank or crown, particularly if it has a folding clasp, or flat on its back. This leaves it in either the vertical or horizontal respectively.

Resting on its side with its tourbillon still effective, the 1993 F.P. Journe tourbillon prototype

The ever-changing position of a wristwatch negates the purpose of the traditional tourbillon that is most effective when the gravity acts perpendicular to its rotational axis. On the other hand, when gravity acts parallel to its rotational axis – this is the scenario when a watch lies flat for example – a tourbillon is arguably ineffective and only serves to waste mainspring energy in the extreme case.

Logically, the solution is for the tourbillon to expand its function to cover a greater range of positions, beyond the traditional vertical orientation.

One solution was is the complex, multi-axis tourbillon that covers all the possible positions. It is made up of multiple tourbillon cages, each rotating on different axes that are generally perpendicular one to another. Together they rotate the regulating organ along several axes, putting it in all possible positions over time.

The near-spherical triple-axis tourbillon inside the MB&F LM Thunderdome

The multi-axis tourbillon emerged surprisingly early when English horologist Anthony Randall built a carriage clock with a double-axis tourbillon in 1980. And even earlier in 1928, German watchmaker Walter Prendel finished a pocket watch with a single-axis tourbillon inclined at 30°, which was conceived for the same purpose of rotating the balance wheel in the maximum number of possible planar positions.

Being substantially taller and heavier, such multi-axis systems are difficult to develop and execute because of tight space and power constraints. Multi-axis tourbillons are surprisingly common in modern watchmaking, particularly from independent watchmakers like Thomas Prescher and MB&F, but even with larger brands like Vacheron Constantin and Jaeger-LeCoultre.

But the multi-axis approach is arguably too fussy and inelegant for François-Paul Journe, who has always prized clarity and slimness in his constructions. His solution was the Tourbillon Vertical.

The Jaeger-LeCoultre Gyrotourbillon 3

The “TV”

The Tourbillon Vertical doesn’t resort to any complicated multi-axis cage designs, but instead repositions the rotational axis of the tourbillon by 90°. It seems like a minor change but the reorientation goes a long way in making the tourbillon effective and consistent across common wristwatch positions.

The Tourbillon Vertical puts the regulator’s rotational axis parallel to the plane of the movement. This means that any horizontal positions of the watch (like placed flat on its back for instance) are covered by the tourbillon’s rotation. According to Mr Journe, long-term precision requires a consistent rate and amplitude for both the horizontal and vertical positions, which is more or less guaranteed by the vertical position of the tourbillon.

Due to its orientation, the Tourbillon Vertical covers most of the positions a wristwatch is commonly placed in. However, since it is not a multi-axis system, there are instances where the gravity pulls down parallel to the tourbillon’s rotation axis, rendering it ineffective. Such occasions, however, are admittedly rare and placing the tourbillon in those specific orientations would require the wearer to position their wrist in awkwardly or unnaturally.

Moreover, Mr Journe logically points out that for majority of people, a wristwatch spends a third to half of the day either on its side or flat, when it is taken off at night. In either position, flat or on its side, the vertical tourbillon is in the same orientation relative to the ground, namely perpendicular. Not only is the tourbillon effective in these positions, the movement can also be regulated with these positions in mind, since they would account for a good proportion of its running time.

A high-speed turn

Observe the Tourbillon Vertical in action and it slowly becomes clear that the carriage goes noticeably quicker. Instead of the conventional one-minute rotation, the cage rotates twice as fast, completing one revolution every 30 seconds. This higher rate of rotation theoretically boosts the Tourbillon Vertical’s capabilities.

Theoretically a fast-rotating tourbillon negates the equilibrium defects of the balance more effectively since the balance is put through a greater number of positions in a period of time. While a classic tourbillon takes a full minute to counter gravity’s effects, the Tourbillon Vertical does it in half the time. This is useful for wristwatches, which are rarely in the same position for long periods, making a fast-rotating tourbillon statistically more effective.

Most classic tourbillons complete one full rotation a minute, simply as a matter of mechanical practicality. The tourbillon cage rotates at the same speed as the seconds wheel rate, since the cage is being driven by a fixed seconds pinion. In fact, tourbillon gear trains often retain the same total tooth count as conventional lever-escapement going trains.

The classic set up in the F.P. Journe Tourbillon Souverain, the immediate predecessor of the Tourbillon Vertical

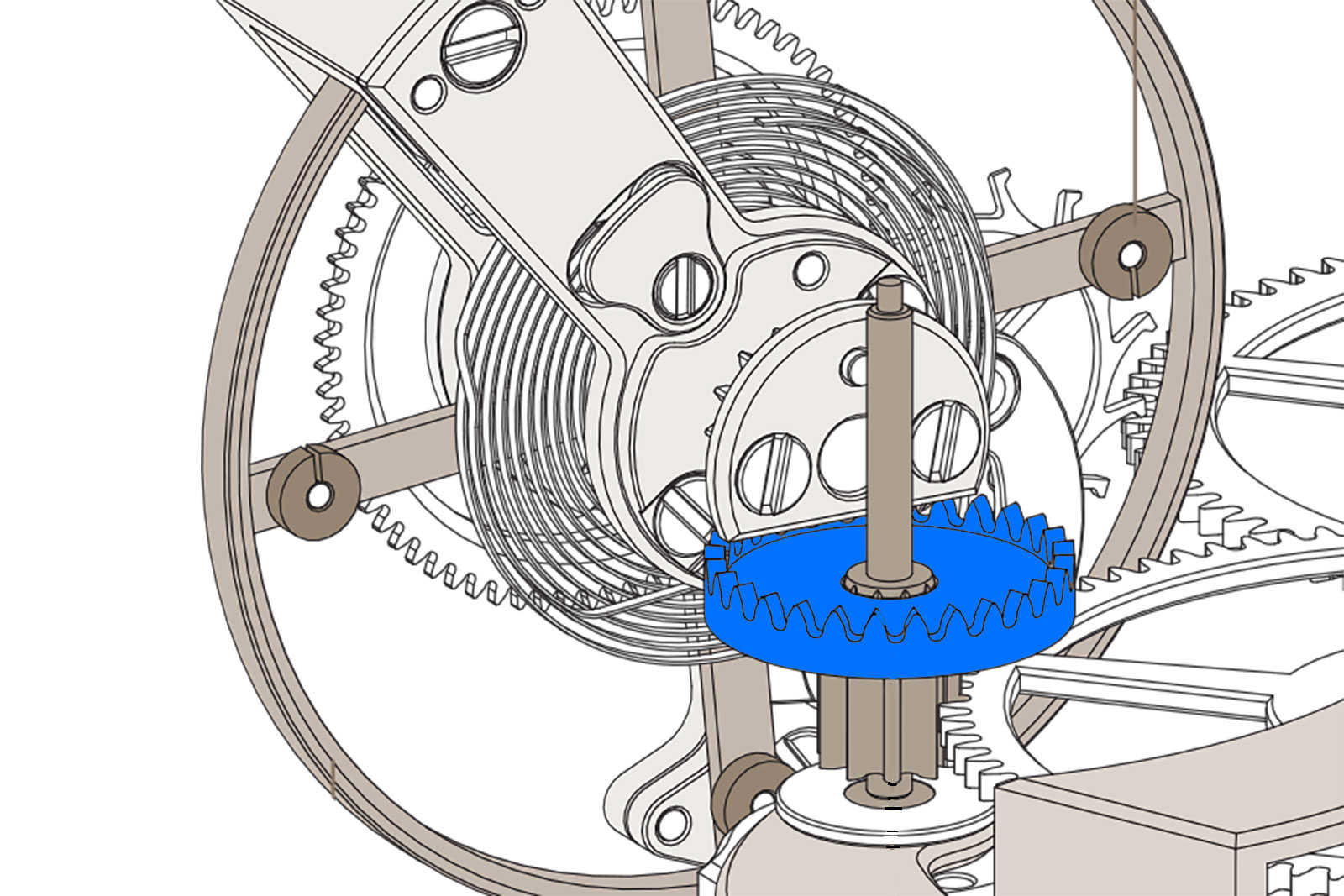

Because of its different position, the Tourbillon Vertical is underpinned by a different mechanical logic. Mr Journe’s choice of a higher speed both useful and intuitive. Because of the 90° angle of transmission between the going train and vertical tourbillon driving pinion, an unconventional connection is required: a 90° lantern gear that engages the tourbillon pinion.

The lantern gear (in blue) sits at a right angle to the tourbillon pinion. Image – F.P. Journe

The transmission ratio between the two components could have been a basic 1:1, but Mr Journe opted for a 2:1 transmission ratio. As such, the crown gear makes one turn every 60 seconds as is convention, but the tourbillon cage is double the speed and makes one rotation every 30 seconds.

In typical F.P. Journe style, its high-speed tourbillon is more mechanically elegant than its counterparts by other brands. Fast-rotating tourbillons by De Bethune or Greubel Forsey require more elaborate gearing in order to accommodate the high-speed rotation of the regulator, because those tourbillons are typically parallel to the plane of the movement.

In contrast, Mr Journe took advantage of the right-angle transmission arising from the vertical position, achieving the 30-second rotational period with no unnecessary complexity.

The vertical orientation of the tourbillon, however, does require extra height since the movement height is equivalent to the diameter of the balance wheel. The cal. 1519 in the Tourbillon Vertical is 34.6 mm in diameter and 10.86 mm high, compared to 32.4 mm and 7.15 mm in the preceding Tourbillon Souverain cal. 1403, an increase in thickness of some 50%.

The tourbillon is perpendicular to the plane of the movement, a position particularly obvious from the back with the red-gold full plate

Vertical construction

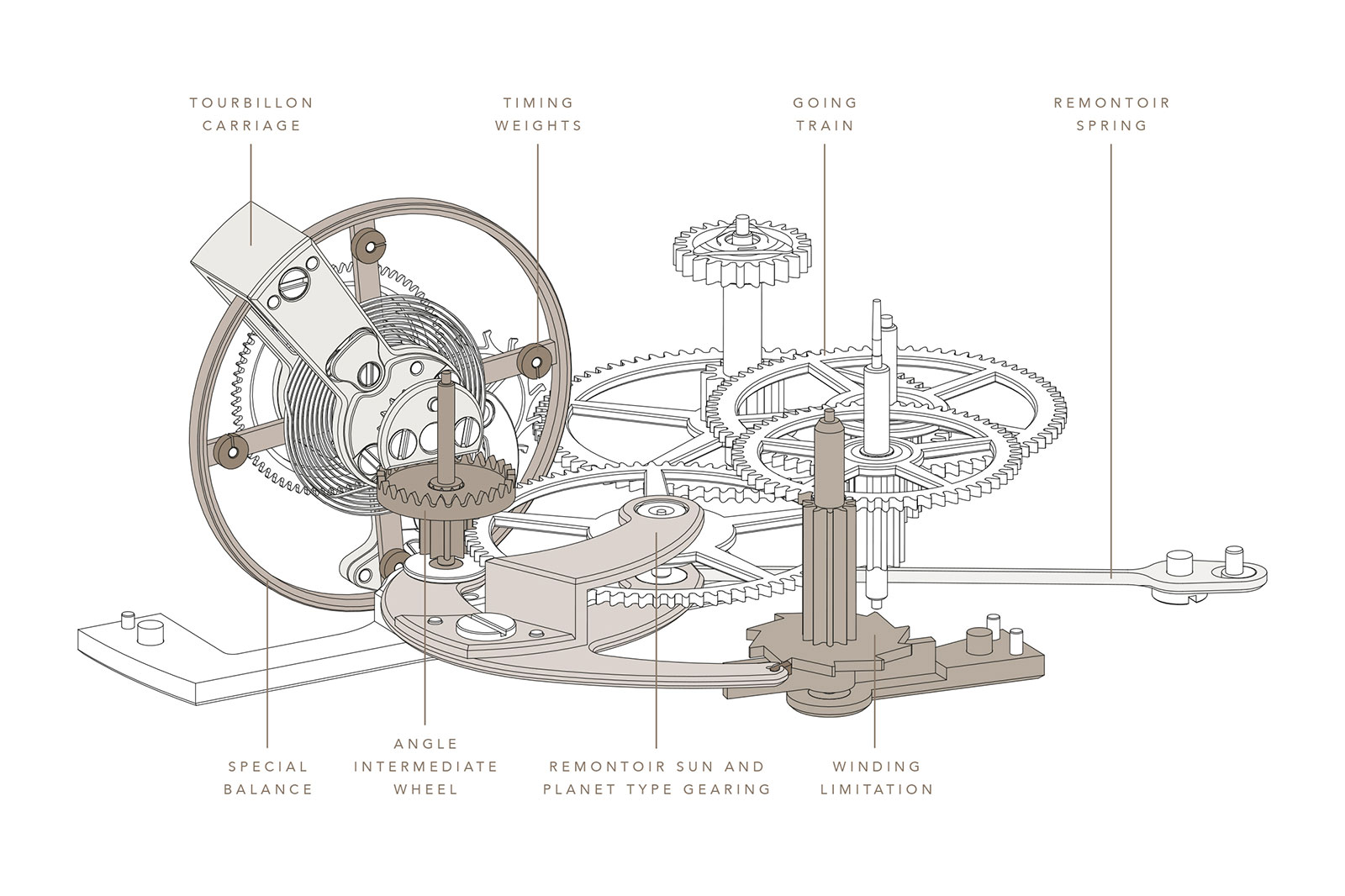

The vertical tourbillon is constructed in the distinctive F.P. Journe style, which makes for some interesting details. As mentioned earlier, the tourbillon cage is driven by a right-angle lantern gear joint (described as a “angle intermediate wheel” by F.P. Journe), which allows the rest of the going train to retain a conventional position.

Interestingly, the tourbillon cage is built upside-down compared to classic constructions. A tourbillon conventionally starts with the tourbillon pinion, followed by the fixed wheel, escapement, and finally the balance wheel. In the Tourbillon Vertical, the layers are inverted, with the balance wheel sandwiched between the driving pinion and fixed wheel.

The construction of the Tourbillon Vertical regulator. Image – F.P. Journe

Compared to typical tourbillons and F.P. Journe’s preceding model, the Tourbillon Vertical has an unusually heavy cage with thick arms. This is easily accommodated by the ample horizontal space in the movement.

Within the carriage is a free-sprung, 3 Hz balance wheel attached to a Phillips overcoil hairspring. Because of space constraints within the tourbillon, the Swiss lever escapement employs a 90° anchor, as opposed to the classic in-line geometry.

Notably, the balance wheel has a moment of inertia of 11 mg/cm^2, higher than the customary 10.1 mg/cm^2 in most F.P. Journe movements, and again made possible by the space in the movement. All things being equal, a greater moment of inertia results in more stable timekeeping over extended periods.

The use of an overcoil hairspring is also notable. Typically associated with chronometers, an overcoil maintains the concentricity of the vibrating hairspring, which in turn improves isochronism and puts less stress on the balance pivots. Such hairsprings are uncommon in F.P. Journe movements, which is surprising and a little disappointing given the chronometrically-oriented nature of its timepieces, though partly explained by the brand’s historical emphasis on maximum thinness, even for complications.

The overcoil hairspring is easily visible due to the vertical position of the tourbillon

As with F.P. Journe’s very first tourbillon, the Tourbillon Vertical is equipped with the brand’s proprietary remontoir d’egalite. A remontoir, or constant force device, is a clever system that assures constant torque flow to the escapement, resulting in stable timekeeping regardless of the mainspring’s state of wind.

Centred on a blade spring and jewelled pallet, the F.P. Journe remontoir was adapted from the gravity-remontoire found in 18th- and 19th-century precision clocks. Now found across the brand’s catalogue in watches as diverse as the Chronomètre Optimum and Vagabondage III, the trademark remontoir stands out as one of the great constant force mechanisms in modern watchmaking, being both simple and effective.

The remontoir in action. Image – F.P. Journe

Regardless of model, the remontoir fulfils the same purpose. As the mainspring is fully wound and then unwinds, the torque it generates fluctuates from excess torque at full wind to declining torque as it runs down. These fluctuations would affect the rate of the movement, but the remontoir eliminates the effect of these fluctuations on the regulator.

The need for consistent torque is even greater for a tourbillon movement because the tourbillon cage needs to be rotated at a reliably consistent speed. The torque requirement is even greater in the Tourbillon Vertical due to the 2:1 driving ratio of the high-speed cage, which puts the last pinion of the going train at a mechanical disadvantage.

All these torque-related issues are mitigated by the remontoir, which acts on the last pinion of the going train. The tourbillon receives near-constant torque for as long as the remontoir is working. The remontoir behaves a little like a capacitor, charging then discharging its load sequentially – one a second in the case of the Tourbillon Vertical.

The remontoir is visible from the back of the Tourbillon Vertical

Concluding thoughts

All in all, the Tourbillon Vertical is a noteworthy update of the classic F.P. Journe tourbillon that arguably makes the tourbillon regulator relevant in the modern era of the wristwatch. It is also a modern F.P. Journe in tangible terms, with the vertical position of the tourbillon dictating a thicker and larger case that measures 42 mm in diameter and 13.6 mm high. Its dimensions are similar to that of the Astronomic, the most complicated F.P. Journe wristwatch ever made.

At the same time, the Tourbillon Vertical also reflects F.P. Journe’s impressive level of vertical integration, particularly for a small, independent brand. It was the first regular production F.P. Journe model to boast a fired enamel dial, which is made in-house at its dial- and case-making facility.

But despite being the newest and most advanced of F.P. Journe’s tourbillons, the Tourbillon Vertical is also a tangible reference to Mr Journe’s original tourbillon prototype of 1993. The three prototypes had no dial, instead the frosted gilt “dial” was the exposed base plate of the movement, while the time-telling was on a silvered guilloche sub-dial. The subsequent Tourbillon Souverain retained the look of an exposed base plate, but the face was in actual fact a dial.

The Tourbillon Vertical once again returns to the original concept, with the grand feu enamel sub-dials mounted on top of the exposed base plate now decorated with clous de Paris guilloche. This reflects the long-running reverence for history in Francois-Paul Journe’s creations, which pay homage to A.-L. Breguet as well as his own works.

This was brought to you in partnership with F.P. Journe and The Hour Glass, the F.P. Journe retailer in Southeast Asia and Oceania. For more, visit Thehourglass.com.

Back to top.