In-Depth: J. Player & Son Supercomplication – All 77 mm of It

The swan song of English complicated watchmaking.

Phillips’s upcoming sale in Geneva has the most attention-grabbing roster of the Geneva auctions, including the return of a record-setting Patek Philippe ref. 1518 in steel. Yet it was the J. Player & Son No. 11’901 that most affected me. Dubbed the “hyper” complication by Phillips, the watch belongs to a rarified group of swan-song supercomplications that memorialise the final days of English fine watchmaking. Despite being over a century old, the watch easily holds its own against the fine watchmaking of today, both in decoration and mechanics.

By the turn of the century, the traditional watchmaking centers of England and France were besieged by vertically integrated American super-factories from the West, and cheap but skilful Swiss labour from the East, both of which benefited greatly from mechanisation. During the waning years of English fine watchmaking, the most prestigious firms responded by attempting to move even further upmarket with highly complicated watches, and the firms remained confident in the appeal of their products.

“If they are more expensive, as they must necessarily be, they last the purchaser a lifetime,” said a representative of Nicole, Nielsen & Co., the company that built this watch, said of English watches in 1912, “The better classes, indeed, have always bought, and will always buy, English-made watches, and will not buy any others”.

Swiss prelude

This watch started life in Switzerland as ebauche number 7’321, according to Fritz Von Osterhausen’s book on Louis Elisée Piguet (LEP), a leading etablisseur in the Vallée de Joux specialised in complications. On December 9, 1902, LEP delivered the ebauche – prepped for, but without its present tourbillon – to Capt & Cie. in Le Solliat, the Swiss arm of London-based Nicole, Nielsen & Co., for 2,100 francs. Incidentally, David Candaux now occupies Capt & Cie.’s former workshop, while Philippe Dufour lives and works just down the same street.

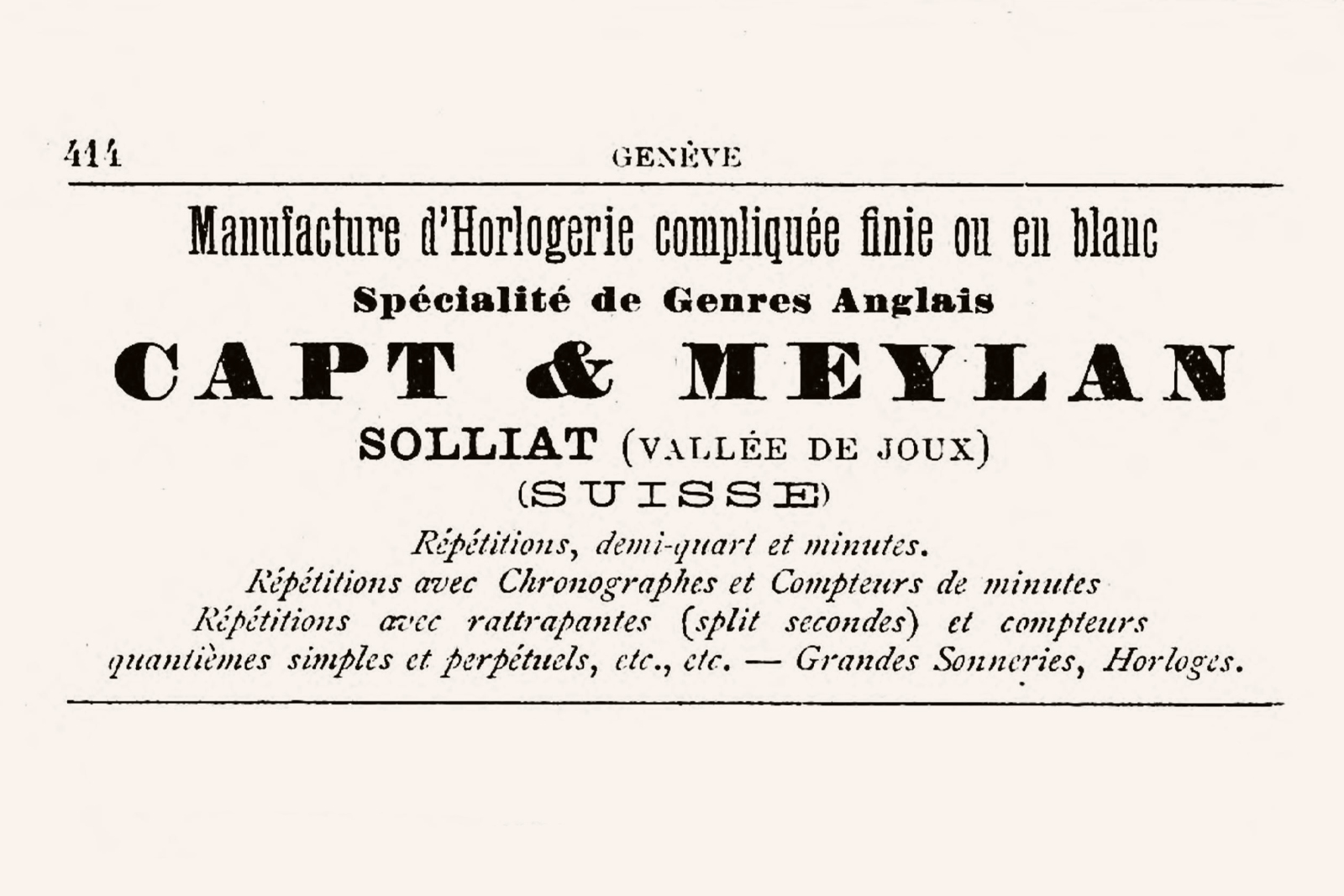

Advertisement in Indicateur Davoine by Capt & Meylan (later Capt & Co) circa 1900. Meaning in English, “Manufacturer of complicated watches and ebauches, specializing in the English style”. Image – Indicateur Davoine 1900

This is the third-highest price recorded in LEP’s books, only surpassed by a pair of two Westminster supercomplications, also made for Nicole, Nielsen. It is hard to say exactly where the present lot ranks, but it is easily among the ten most complicated English watches, and is probably the most complicated with only a single dial.

Adolphe Nicole founded his firm in 1839 as Nicole & Capt. The company later became Nicole, Nielsen & Co. when Danish watchmaker Sophus Emil Nielsen joined as partner around 1870. Besides founding the company, Adolphe Nicole – or one of his employees – invented the modern chronograph, and possibly also the rattrapante.

The firm was the leading manufacturer of high-end and complicated English watches, supplying most renowned brands like Dent, Frodsham, Smith, etc. Nicole Nielsen could make most of their simple watches domestically, but still relied on their partners across the channel for highly complicated ebauches. But they were not alone, as the best firms from Geneva, Paris, and Dresden did the same.

The movement probably reached London in 1903, still without a tourbillon. Nicole, Nielsen completed the watch for J. Player & Son, a Coventry firm that retailed J.P. Morgan’s astronomical watch – also furnished by Nicole, Nielsen.

A line engraving of the watch appears in a 1990s reprint of 1910 Nicole, Nielsen & Co. catalog as the “Type 52”, with pricing on request. From there I tracked it to a 1993 Christie’s auction in New York, where the current owner won it for almost US$600,000, after which the trail ran cold, until now.

First encounter

The watch makes a strong first impression, dominating the other watches in its display case. Pocket watches display better than wristwatches – especially 77 mm ones. Bigger is better when it comes to pocket watches, at least to a point, and this is possibly a little past that point.

London dial manufacturer T.J. Willis made the enormous vitreous enamel dial for this and most other English complications of the day. Each of the five sunken sub-dials are separate parts, soldered into the main dial. While proportionally small, in absolute terms each sub-dial is quite large and easy to read.

The front and back of the dial, signed “Willis”. Image – Phillips

The lettering is hand painted, and intentional. The month sub-dial uses serifed letters for every month except January to mark the new year. The lettering also shifts styles to add emphasis, such as the sans-serif J. Player & Son signature, and “before” and “after” on the equation of time arc.

The equation of time expresses the difference between local mean solar time (or clock time) and apparent solar time (or sundial time), which defines noon as when the sun is at its highest point in the sky and varies over the course of the year. Unlike time of sunrise or sunset indications, which must be re-cammed for a different latitude, the equation of time is based on longitude, and will work for any location if you set the watch to local time.

The up/down scale shows the hours since last winding, with “up” being fully wound and “down” being fully exhausted. When fully wound, the watch will probably run for 30 hours or so. However, the scale ends early at 24 hours, marked “wind”, as winding a watch every 24 hours gives the best performance.

The hands show their age more than the enamel dial, but their quality is still evident. While the hour hand appears ordinary at first glance, it is significantly more substantial and three-dimensional than normal spade hands. The rose gold equation hand is another standout, appearing to be welded together from multiple parts.

To help differentiate the two seconds hands, the split seconds hand is gilt and topped with a star while its counterweight is arrow-shaped. Both hands bend ever so slightly towards the dial, making them easier to read against the sub-seconds scale. And then there is the enamelled gold moon phase disk. It is highly polished, with stars engraved through the enamel to reveal the gold underneath, while the moon is delicately textured.

As for the perpetual calendar, from images of the under dial works it appears to be of the instantaneous variety, using a cam (red) and spring (blue) to store energy before releasing it instantly around midnight – which also makes it difficult to damage the calendar by using the quick adjustment tabs (secreted under the front bezel) at an inopportune moment. The calendar is attributable to Leon Aubert, being a perfect match to one of the master’s drawings shared by his grandson Daniel Aubert.

Pressing the tab at three o’clock advances the day, date, month, leap year, and equation of time in sync, while the tab near six o’clock adjusts the moon phase individually. There is no quick correction for just the month, as that would de-synchronise the equation of time, which is controlled by the large kidney shaped cam (yellow) and read by a spring loaded rack (green). You can also spot a bimetallic strip for the thermometer from 10 to 12 o’clock.

Image – Phillips, annotated by the author

A six function crown

Despite its complication and age, the watch is easy to understand and use as everything is labelled, including the “alarum” – a spelling no longer in use today. Turning the crown clockwise winds the strike barrel, and counterclockwise winds the timekeeping barrel, which is the norm for two-train clock watches.

Holding the button right of the crown allows you to wind the alarm. The crown doesn’t pull out to set – known as negative setting – like on most Swiss or American watches of the time. Rather, turning the crown while holding the pin to the left sets the time (and automatically disables the strikes while doing so) while the pin to the left allows you to set the alarm.

Image – Phillips

A pocket-sized grandfather clock

Traditionally, the term “clock” meant a timepiece that chimes the hours – from the Latin word clocca, meaning bell – which is where the term “clockwatch” comes from. This watch chimes on three gongs, with a fourth for the alarm. During my time with the watch, it happily chimed under its own power, with good cadence. The enormous scalloped case acts as a resonance box, and the chimes sound best with the case back closed.

In “hours” mode, the watch strikes out the full hours and quarters each quarter. Francophones use the term grande sonnerie to describe this functionality. In “quarters” mode (petite sonnerie) the watch strikes out just the quarters on the quarters, and only strikes the hours on the new hour – which is less annoying and also extends the power reserve. Pressing the button at three activates the trip minute repeater on demand.

Watchmaking of the highest calibre

The 27.5”’ calibre is one of the most impressive movements I’ve seen, partially because of its complication and exquisite decoration, but also its domineering size – about 62 mm. For comparison, the movement in the Henry Graves Supercomplication is only 25”’, or about 56 mm in diameter.

A massive, gilt, three quarter plate conceals most of the movement, as is the English way, drawing all focus to the enormous tourbillon. The tourbillon subassembly is approximately 20 mm in diameter, larger than many entire movements.

An English heart

In Watches, George Daniels claimed a Nicole, Nielsen tourbillon “…is as fine a watch as has ever been made, and one whose performance can hardly be bettered.” Of course, Daniels was more than a little biased towards English watchmaking, but I cannot argue with his assessment. The Swiss were hesitant to combine tourbillons with complications, while the English were eager, going so far as to hide them inside complicated duo-face watches.

This tourbillion in particular is among the finest made by the firm, using a “duo-in-uno” or semi-helical hairspring – half flat and half helical. The justification being it is more compact than a helical hairspring while being similar in terms of performance. Notice how the specular polished arms of the cage step upwards to accommodate the helical section. James Ward Packard and Elliot Cabot Lee both owned complicated Dents with this type of tourbillon. The latter has an extremely similar chronograph, and is coming to auction in New York this December.

Something of a calling card for Nicole, Nielsen, the late horological scholar Reinhard Meis dubbed this style of open-worked half-bridge the “Nielsen 2” style. In fact, there are two other lots in the same auction with it: Frodsham no. 09’857, one of the many minute repeating tourbillon rattrapante watches made for J.P. Morgan, and S. Smith & Son no. 1’900-1, a triple complication with tourbillon.

Image – Phillips

It is equipped with an English lever escapement, using a ratchet-toothed brass escape wheel rather than the typical club-tooth steel escape wheels of the Swiss lever. The latter geometry is more efficient, with smaller drops, though in practice both could perform extremely well. If anything, the English escape wheel’s greatest weakness was its fragility, not its slight inefficiency, requiring a lighter and more careful hand from the watchmaker.

The anchor appears unjeweled at first glance as the jewels are held in place from the top and bottom, rather than the sides as on Swiss levers. The Germans did the same, though their levers (and escape wheels) were often hardened gold rather than steel. There are cap jewels on both the escape wheel and fork pivots, and a gold weight on the other side of the cage to balance the escapement’s weight. I cannot say for sure without partial disassembly of the tourbillon, but the cap jewels for the balance are possibly diamond.

Chronograph

Like many complicated English tourbillons, an oscillating pinion links the tourbillon cage to the chronograph seconds wheel. Pressing the crown starts, stops and resets the chronograph, while the button to the right of the crown toggles the rattrapante. The chronograph works take a circuitous route around the movement. The linkage between the column wheel and oscillating pinion snakes across the alarm bridge, which is free-hand engraved with “J. Player & Son, Coventry & London” and the serial number.

There is an unoccupied screw hole within the chronograph seconds wheel, probably meant to secure the friction spring that prevents the chronograph seconds hand from jittering. Or, it might not be missing at all, and was relocated at the last minute to under the chronograph seconds wheel bridge for aesthetics – like many other English chronographs – leaving an unused screw hole.

If it is missing, it would be an easy replacement for any skilled watchmaker. In theory, every part can be repaired or refabricated if needed, to keep the watch going for centuries ahead.

Key facts

J. Player & Son No. 11’901 (Nicole Nielsen Type 52)

Diameter: 77 mm

Material: 18k yellow gold

Crystal: Glass

Water resistance: Dust and moisture resistant only

Movement: 27.5”’

Functions: Hours, minutes, running seconds, grande et petite sonnerie on three gongs, trip minute repeater, tourbillon, alarm, instantaneous perpetual calendar, moon phase, equation of time, split seconds chronograph with 60 minute counter, wind indicator, thermometer.

Winding: Manual

Frequency: 18,000 beats per hour (2.5 Hz)

Power reserve: ~30 hours

The J. Player & Son no. 11’901 has an estimate of CHF400,000-800,000, or about US$501,000-1,000,000, and it will be sold Watches: Decade One (2015–2025) auction on November 8, 2025 in Geneva.

For more, visit Phillips.com.

Back to top.