Ulysse Nardin Illuminates the Freak S with Flinqué Enamel

Freaky and flinqué.

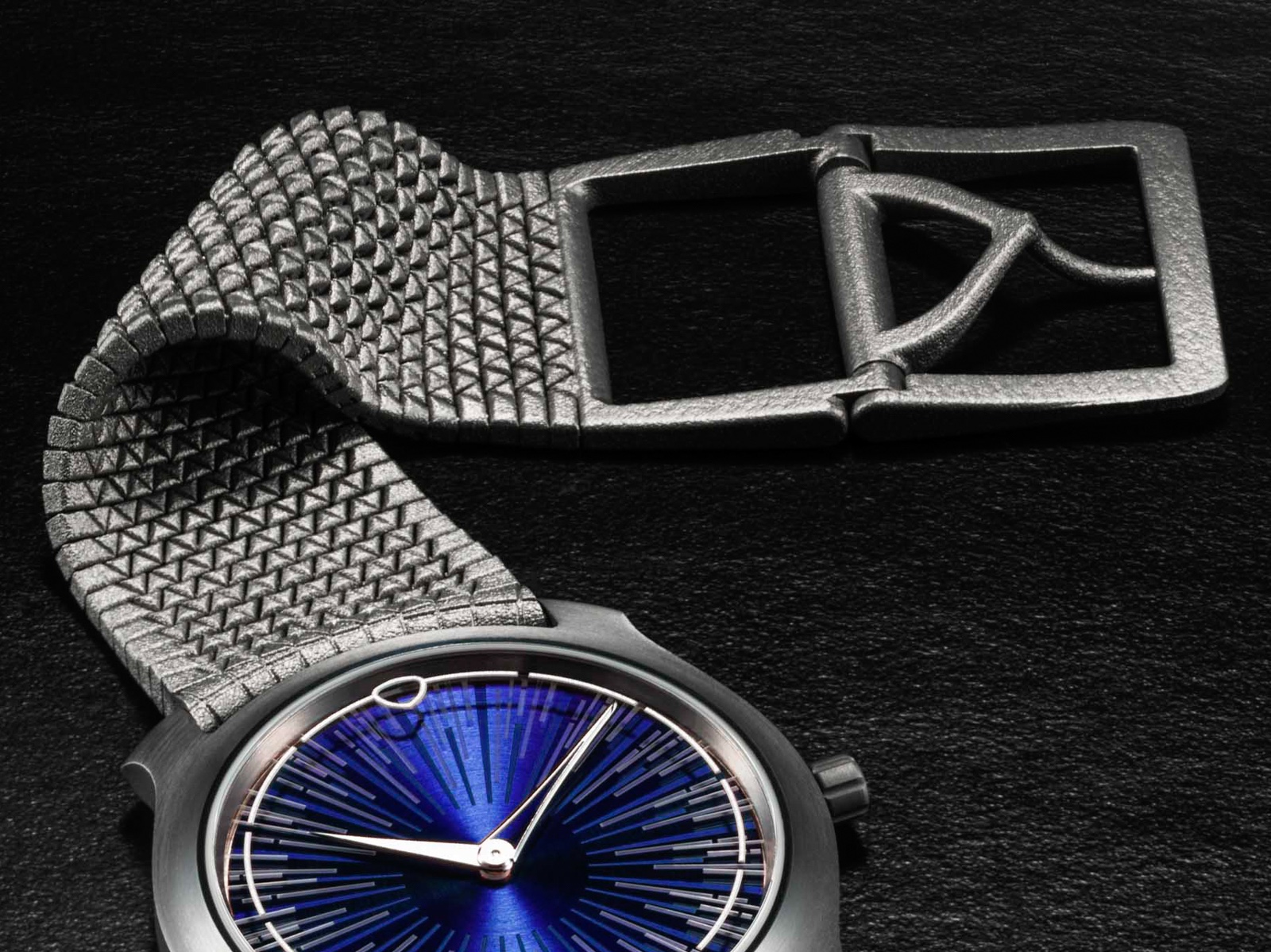

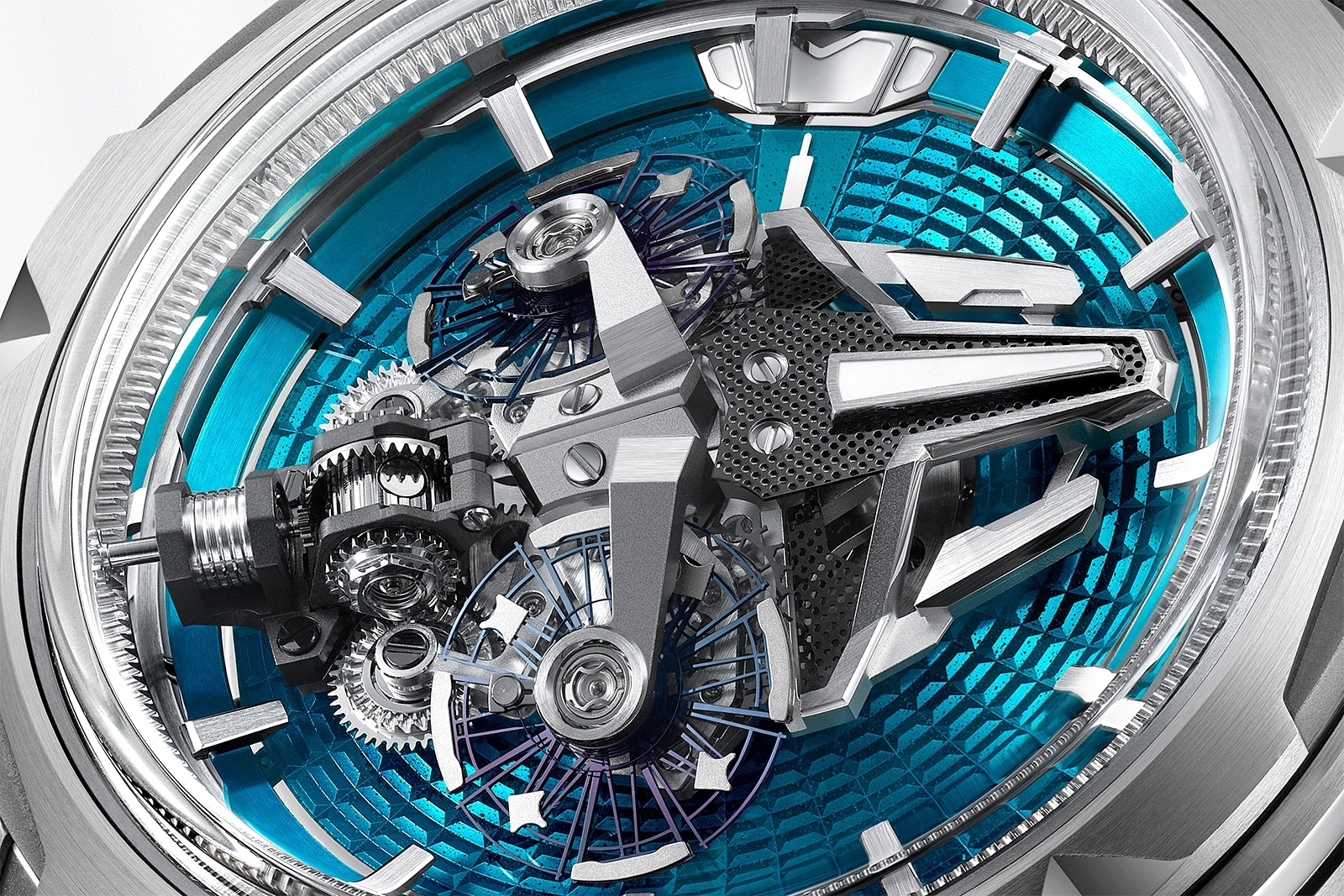

Ulysse Nardin has revealed a new take on its flagship complication, the Freak S Enamel, now offered with a silvery titanium case and with the choice of either red or turquoise translucent flinqué enamel over an engine-turned guilloché dial. While mechanically unchanged, the cleaner case design and high-gloss dial plate transform the overall visual impression and intensify the focus on the central carousel, which serves as both the time display and the heart of the movement.

A limited edition of 50 pieces in each colour, the enamel edition is the fourth member of the Freak S family, which was launched in 2022 as a higher-end, dual-balance evolution of the Freak Vision.

Initial thoughts

Since its debut a quarter century ago, the Freak collection has given Ulysse Nardin (UN) freedom to push the boundaries of movement design. While the usually crownless case and central carousel have become familiar over the years, each iteration still manages to feel like an experiment.

The new enamel edition is the most aesthetically restrained Freak S yet; paradoxically, it also feels the most luxurious, trading exotic material combinations for polished titanium and brightly coloured enamel. The result is a watch that feels as radical as ever, but more refined.

The 45 mm case, for example, is the simplest Freak S case to date: no carbon flanks, and no PVD coating. The traditional brushed and polished finish helps the large case fade into the background to allow the enamel dial and starship-like carousel to really shine. For a collection known for its hyper-aggressive styling, the return to a more natural metallic finish somehow feels fresh.

The same is true of the rotating dial plate, which features a new radial fluted guilloché pattern coated in transparent flinqué enamel. Available in either red or turquoise, the enamel adds welcome colour without stealing focus from the carousel. In fact, the presence of a raised retaining ring around the guilloché disc has the optical effect of shrinking the dial, making the carousel appear even larger than it does in other Freak S models, which is an unexpected but welcome tweak to the proportions.

Unfortunately, the press images reveal the presence of tiny air bubbles in the enamel, giving the dial a slightly dirty texture under magnification. To be fair, it’s possible these are pre-production samples, and the final product may be better. Either way, at arm’s length the effect is rich and satisfying, and the central carousel remains the star of the show.

The Freak has never been a cheap watch, historically positioned at or near the top of the range for UN. That said, it’s always offered a unique value proposition, being so original in concept. This holds true for the Freak S enamel, which is set to retail for CHF153,000 including Swiss VAT. The double balance system linked by a differential is typically a six-figure proposition in its own right; putting a system like this on a carousel ups the ante, to say nothing of the Freak’s unmistakeable visual identity and historical significance.

Freaking familiar

The engine powering the Freak S enamel is the same UN-251 movement we’ve covered in-depth before. While visually chaotic, the movement is conceptually elegant, with a carousel mounted to a fixed ring gear, driven from its center, that rotates once per hour to act as the minute hand. Underneath, the dial plate doubles as the top of the mainspring barrel and makes one rotation every 12 hours, serving as the hour hand.

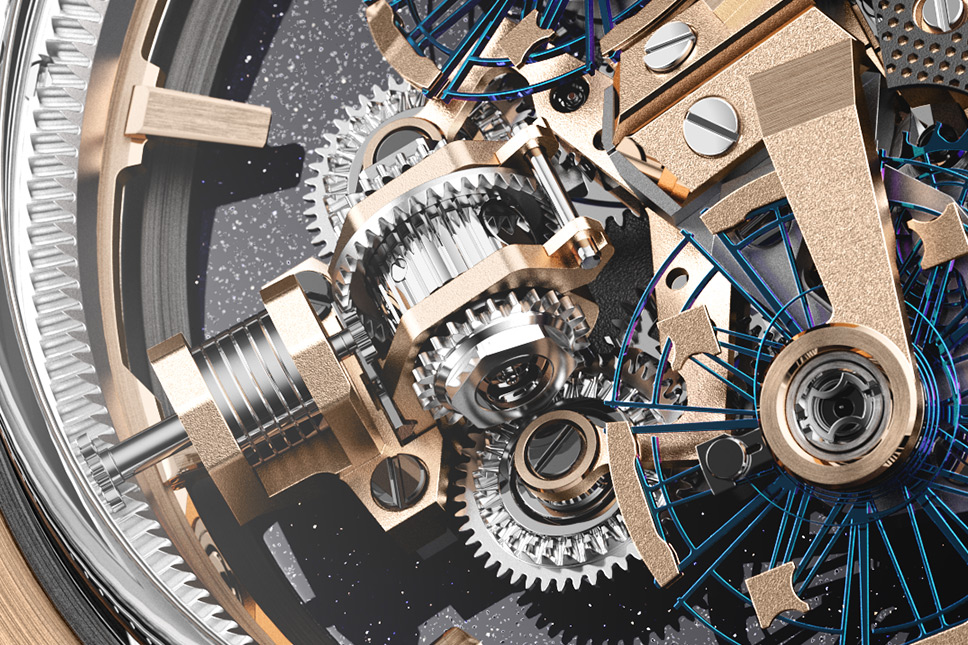

The movement architecture is extravagant, using every bit of space within the case for maximum effect; it’s one of those watches you wouldn’t want to be any smaller. The differential, exposed in all its glory, is a visual feast for the mechanically inclined, an effectively averages the rates of the twin free-sprung balances.

A close-up of the differential, shown here in the original Freak S from 2022.

Without a seconds hand, the effect is difficult to measure; the value is primarily intellectual. That said, the movement is tested to a standard similar to COSC, ensuring that each Freak S runs within 0 to +10 seconds per day. The timekeeping performance is assisted by an especially efficient proprietary winding system called the Grinder, named after the winch systems used on sailing yachts.

The Grinder system use four pawls to wind the watch quickly and keep the mainspring within the optimal segment of its torque curve. Taken together, these attributes make for a singular and intellectually coherent whole.

The Grinder automatic system is shown here in the original Freak S.

Dialling up the colour

While the movement hasn’t changed, the dial plate most certainly has. In the short history of the Freak S, UN has dressed the dial plate in a variety of materials, including aventurine glass for the debut and raw guilloché and crystallised ruthenium for subsequent editions. Flinqué enamel seems almost mainstream by comparison, but it works well.

The hand-turned guilloché dial is engraved in-house the old fashioned way, and the radial fluted pattern creates a stadium-like feel, with the focal point on the rotating carousel. As is common for high-end enamel dials, the dial base itself is made from a white gold alloy with a high palladium content, chosen specifically for its resistance to thermal expansion. Thermal stability is crucial, because the enamel must be fired repeatedly at temperatures approaching 800° C, and any warping would render the dial unusable.

The engraved dial base is then painted with enamel paste and fired repeatedly until the correct colour and depth are reached. The glowing, refractive nature of the richly coloured translucent enamel enhances the look of the signature carousel.

Key facts and price

Ulysse Nardin Freak S Enamel

Ref. 2513-500LE-6AE-RED/3A

Ref. 2513-500LE-3AE-TUR/3A

Diameter: 45 mm

Height: 16.65 mm

Material: Titanium

Crystal: Sapphire

Water resistance: 30 m

Movement: UN-251

Functions: Hours and minutes

Winding: Automatic

Frequency: 18,000 vibrations per hour (2.5 Hz)

Power reserve: 72 hours

Strap: Rubber strap with titanium folding clasp

Limited edition: Yes, 50 pieces in each colour

Availability: At Ulysse Nardin boutiques and retailers

Price: CHF153,000 including 8.1% VAT

For more, visit Ulysse-nardin.com

Back to top.