The Oregon High Desert might seem like a strange place to find a watchmaker, but if you happen to stop in Bend, the region’s largest city with about 100,000 residents, you’ll have a chance of running into Keaton Myrick.

Inspired by the likes of George Daniels and Philippe Dufour, Mr Myrick produces largely handmade watches in small numbers for connoisseurs of independent watchmaking. Setting up shop this far from the robust supplier networks of Switzerland has proven challenging, but Mr Myrick’s story of overcoming these headwinds reveals a degree of resilience and independence that embodies the spirit of the American West.

We’ve been following Mr Myrick’s career for more than a decade, profiling him in 2013 after he debuted his first watch at Baselworld 2012. Now delivering the final pieces of his 1 of 30 series, Mr Myrick has moved into a new, larger workshop and evolved many of his manufacturing processes, so we thought it was worth a visit to see what’s in store for the future of watchmaking in the Pacific Northwest.

A later example from the ‘1 in 30’ series.

Origins

As you might have guessed, Bend, Oregon is not a hotbed for watchmaking. In Mr Myrick’s case, pursuing a career in watchmaking meant relocating across the country to study at the Lititz Watch Technicum (LWT) in Pennsylvania, where he became WOSTEP-certified and began his stint at Rolex, working in after-sales service and restoration.

The founder at his bench.

But it was not long before Mr Myrick’s independent nature compelled him to leave the safety of a corporate watchmaking career and set up his own shop. He moved back home, to the majestic beauty of the Pacific Northwest, and began doing freelance restoration work while developing his first wristwatch.

While Mr Myrick’s time at LWT prepared him for his early career at Rolex and gave him the idea to create his own watch, it did little to equip him with the skills needed to become an independent watchmaker; those skills he picked up doing restoration work.

It was the process of restoring historical clocks, pocket watches, and marine chronometers that exposed him to devices like the grande sonnerie-style winding click that would later find their way into his own work. “In some ways I find high level restoration work to be more challenging than manufacturing,” notes Mr Myrick, “I believe restoration should be the foundation for anyone wanting to manufacture watches.”

Growing pains

As an independent watchmaker, Mr Myrick acknowledges he got off to a rough start and made some early decisions that limited his ability to deliver consistently. For example, he initially did not expect to have to make his own cases in-house, but after an order was canceled by his supplier at the last minute (the supplier pushed back his delivery date to prioritise an order from a larger brand), he realised the lack of control was untenable, and began investing in this capability.

Conversely, he also tried to do too many of the wrong things at the beginning. For example, he went to great lengths to make as much of the movement himself as possible, even making each individual screw by hand at a cost of between US$80 and US$110 per screw. He later realised this was a misallocation of his time, and has subsequently found a reliable external supplier that provides screws for his needs.

A Haas OM1 CNC machine.

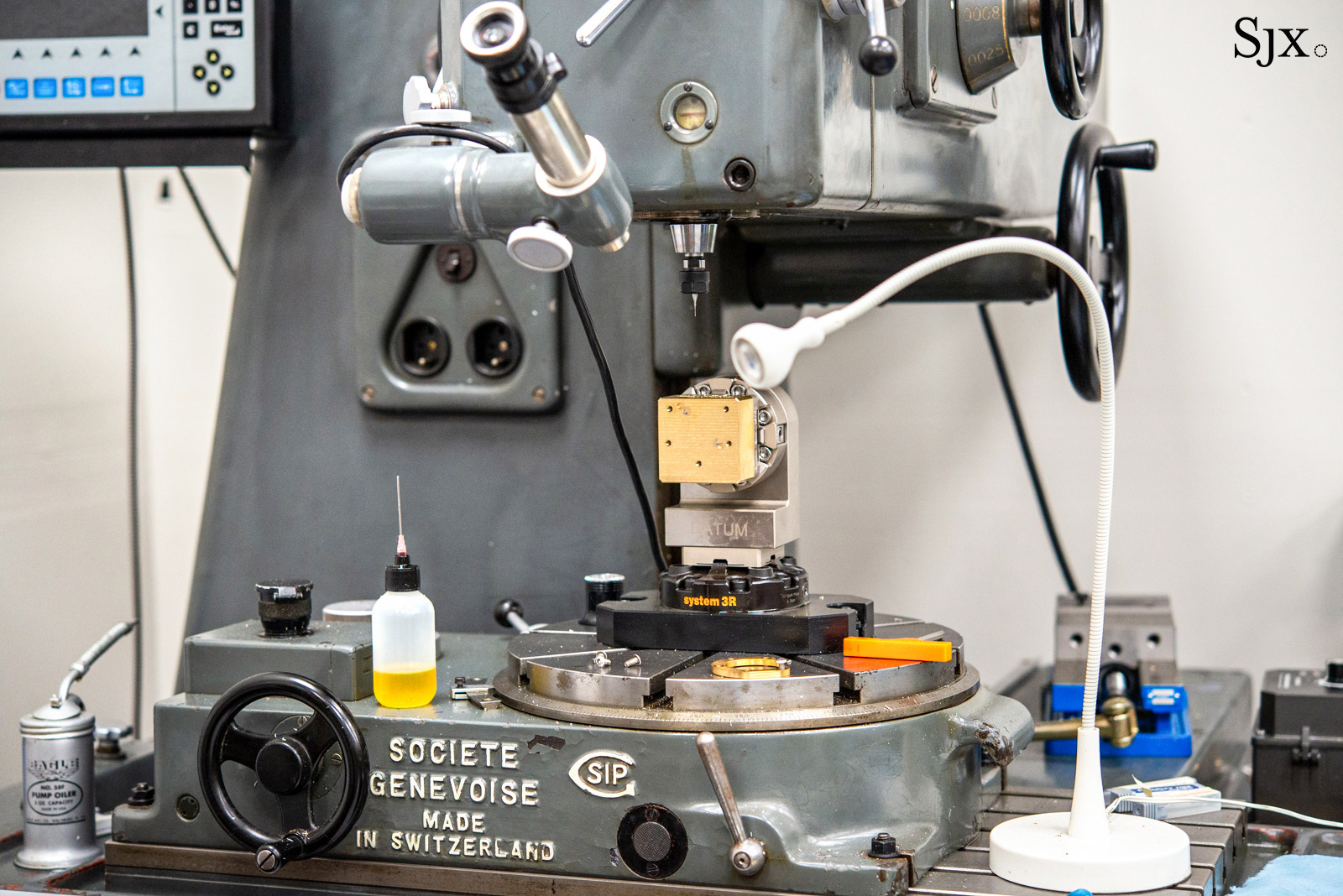

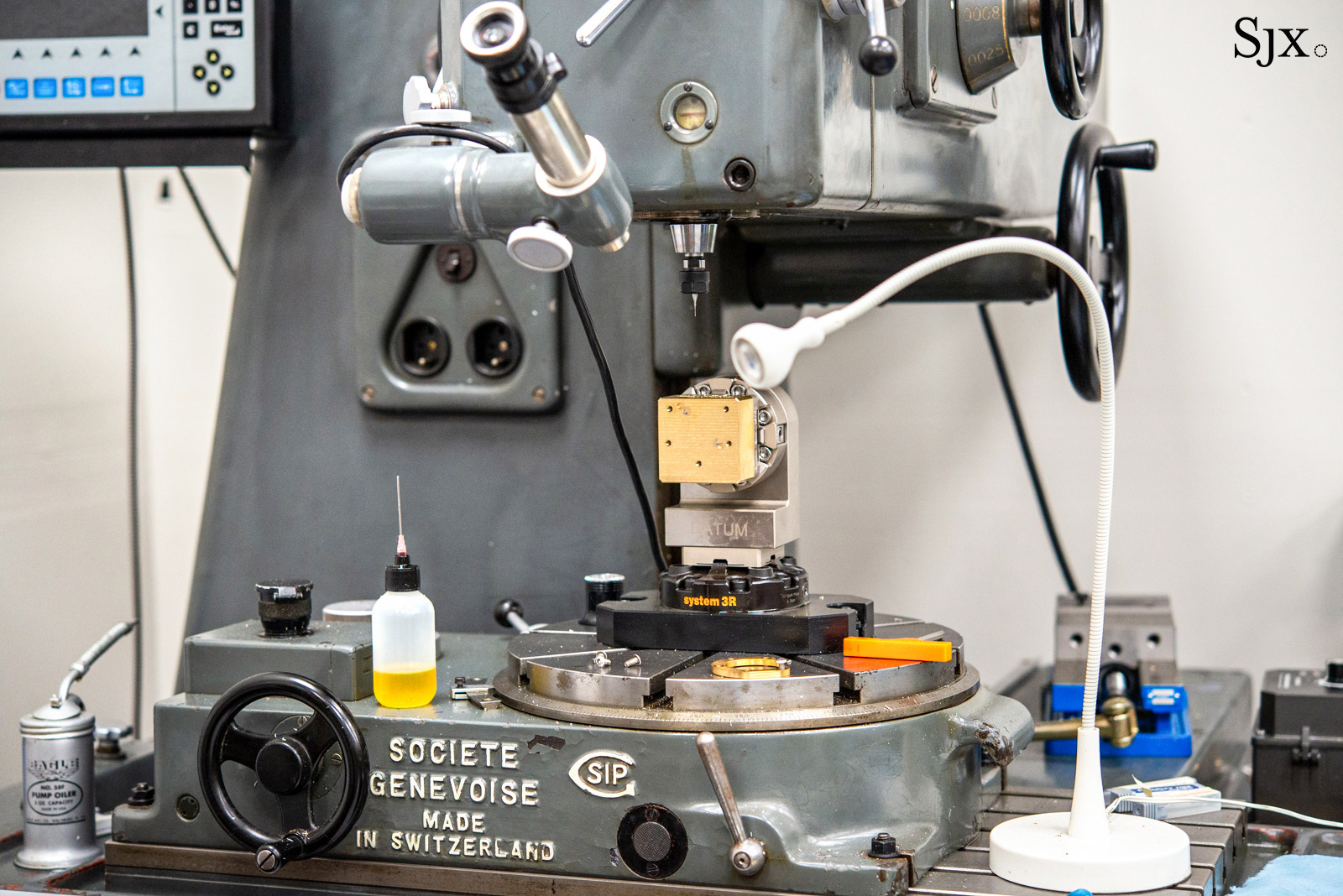

More recently, he has been able to drastically increase his production efficiency by migrating to a zero-point headstock system from Sweden-based System 3R. This system enables Mr Myrick to seamlessly transition components between various lathes, including his straight-line and rose guilloche engines and his CNC machine.

This system required retrofitting some of his antique lathes, but reduces the amount of time required to set up and adjust machines between operations, meaning he can take a zirconium dial straight off the rose engine and put it in his CNC to drill screw holes, all with minimal adjustment.

An antique milling tool, modified by Mr Myrick to be compatible with the universal System 3R headstock system.

Stable footing

Some of these operational changes coincided with his move to a new, larger workshop in 2021 that provided enough space for all the new tools. Since then, Mr Myrick has nearly caught up on his scheduled deliveries and has begun conceptual development of his new series, which will be limited to 28 pieces.

While about 80% of his time is allocated to producing and delivering his own watches, his revenue stream is diversified by making components for other independent watchmakers and selectively accepting pieces for restoration, primarily from his existing client base.

Going into 2025, Mr Myrick is on track to produce 5-6 watches per year. For a bespoke watch, he quotes a 2.5 year delivery time, but believes that to be a conservative estimate. As the sole proprietor of his business, Mr Myrick has no external investors, beyond the clients who entrust him with their deposits.

Mr Myrick is not afraid of using advanced tools like this laser engraving device, which is used for engravings on the new, slimmer case backs.

What happens in the workshop

In total, Mr Myrick produces just over 80% of the components for his watches in his workshop. While the conceptual architecture for the cal. 29.30 is based on the ubiquitous ETA 6497, there’s nothing industrial about it by the time he is finished.

While Mr Myrick uses US-sourced materials whenever possible, he prefers to use the best materials he can get, even if that means choosing a European supplier. For example, US-sourced German silver does not patina in the same way, and is more difficult to machine, than material produced in Europe. For these reasons, he sources raw German silver from a supplier in Europe, before machining it in-house to produce the mainplate, bridges, and dials for his watches.

A balance bridge made in rose gold.

The batwing-shaped balance bridge is inspired by observatory tourbillon calibers like those made by Patek Philippe and Jaeger-LeCoultre. While typically offered in black-polished steel, Mr Myrick has made the skeletonised bridge in rose gold upon request. Interestingly, he notes that compared to a steel bridge, gold is soft enough to actually add a bit of extra shock protection for the balance staff, though in practice this is likely more of a piece of trivia than anything, since the Incabloc system does most of the work of protecting the movement from shock.

For balance springs, Mr Myrick is working through his stock of Nivarox 1 hairsprings, the same material used by elite brands across the industry. That said, he has a soft spot for traditional Elinvar, which George Daniels considered the gold standard for hairsprings. He’s recently acquired a stock of vintage size 10 Elinvar hairsprings, which he plans to use for a future project.

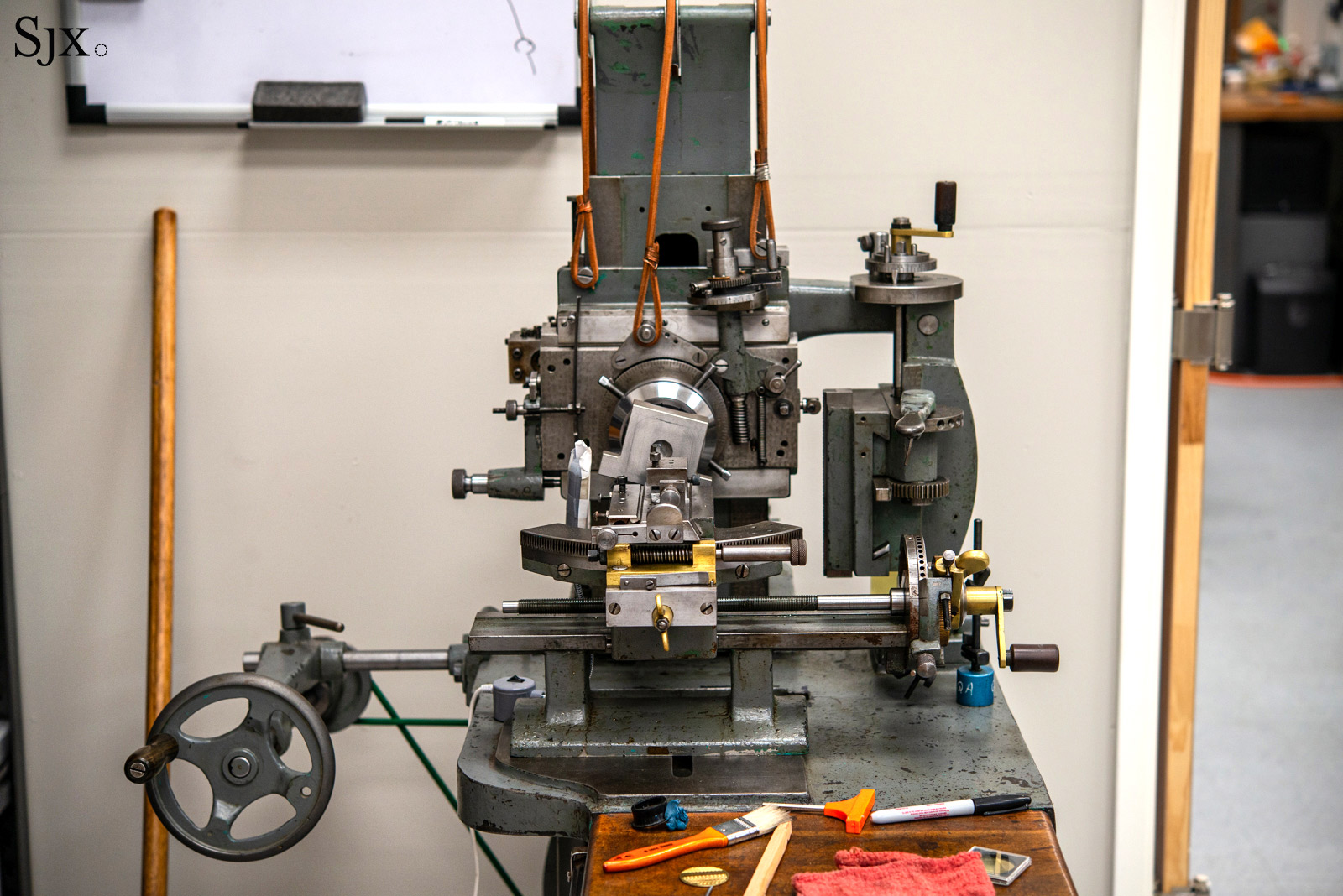

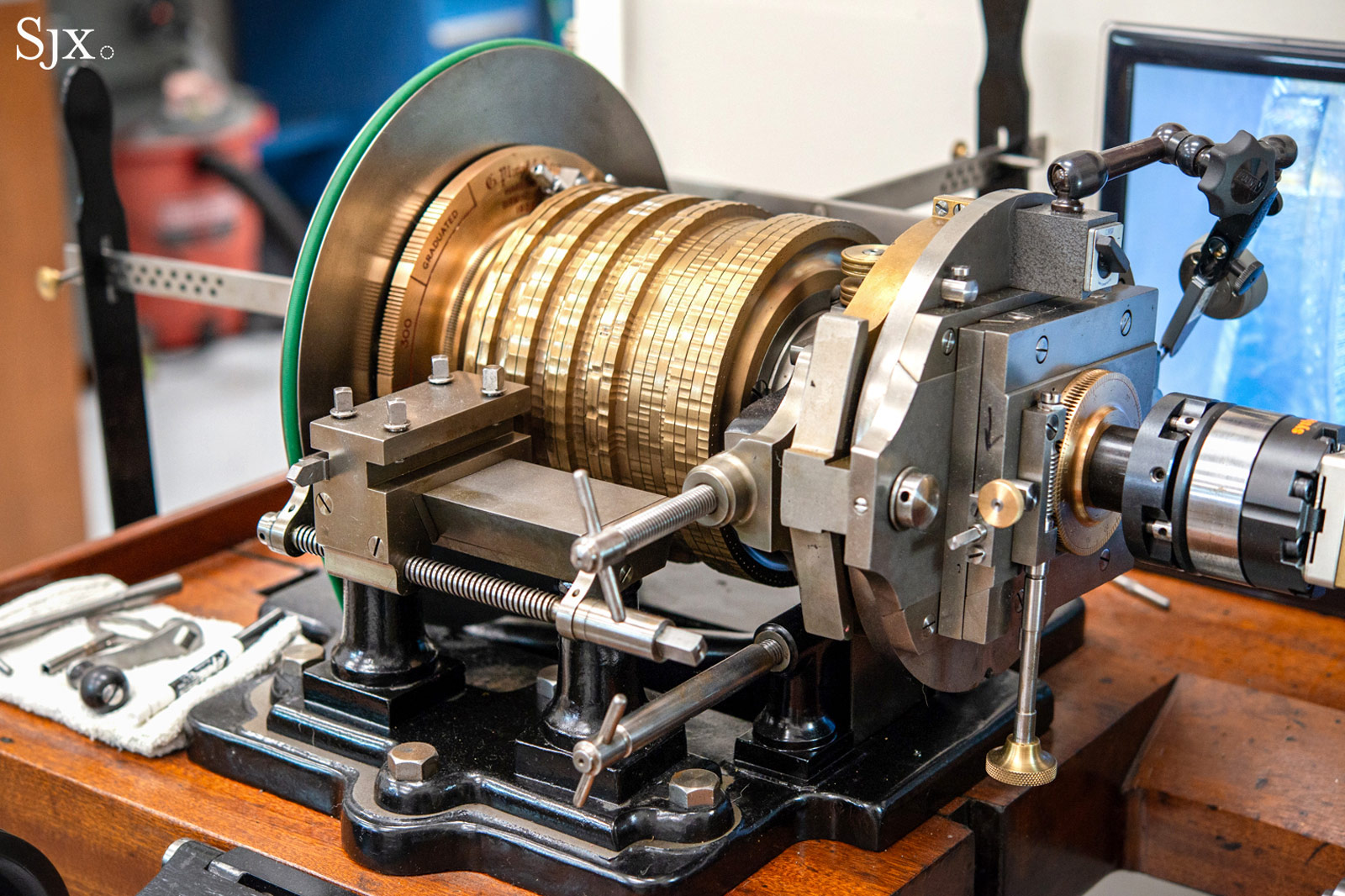

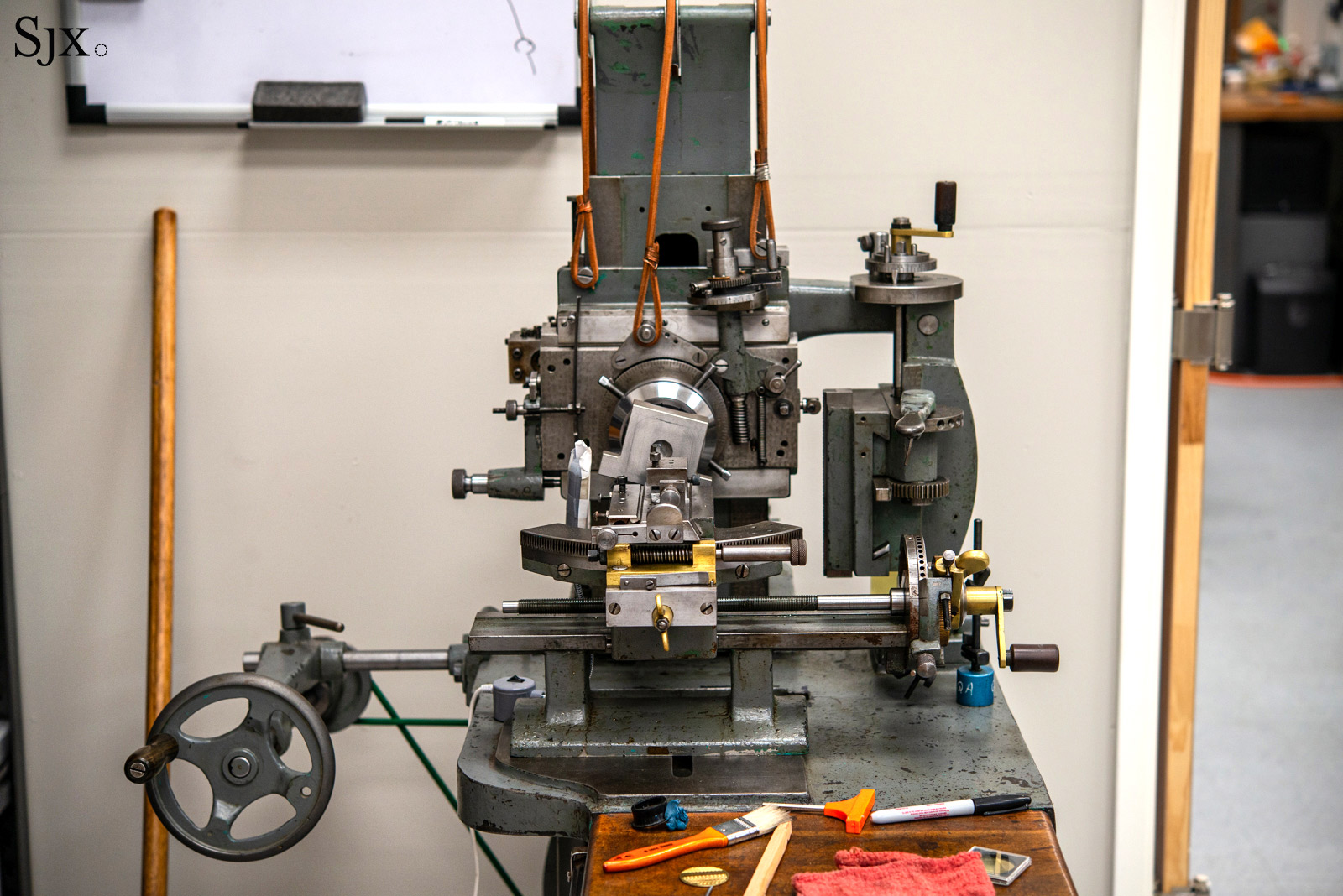

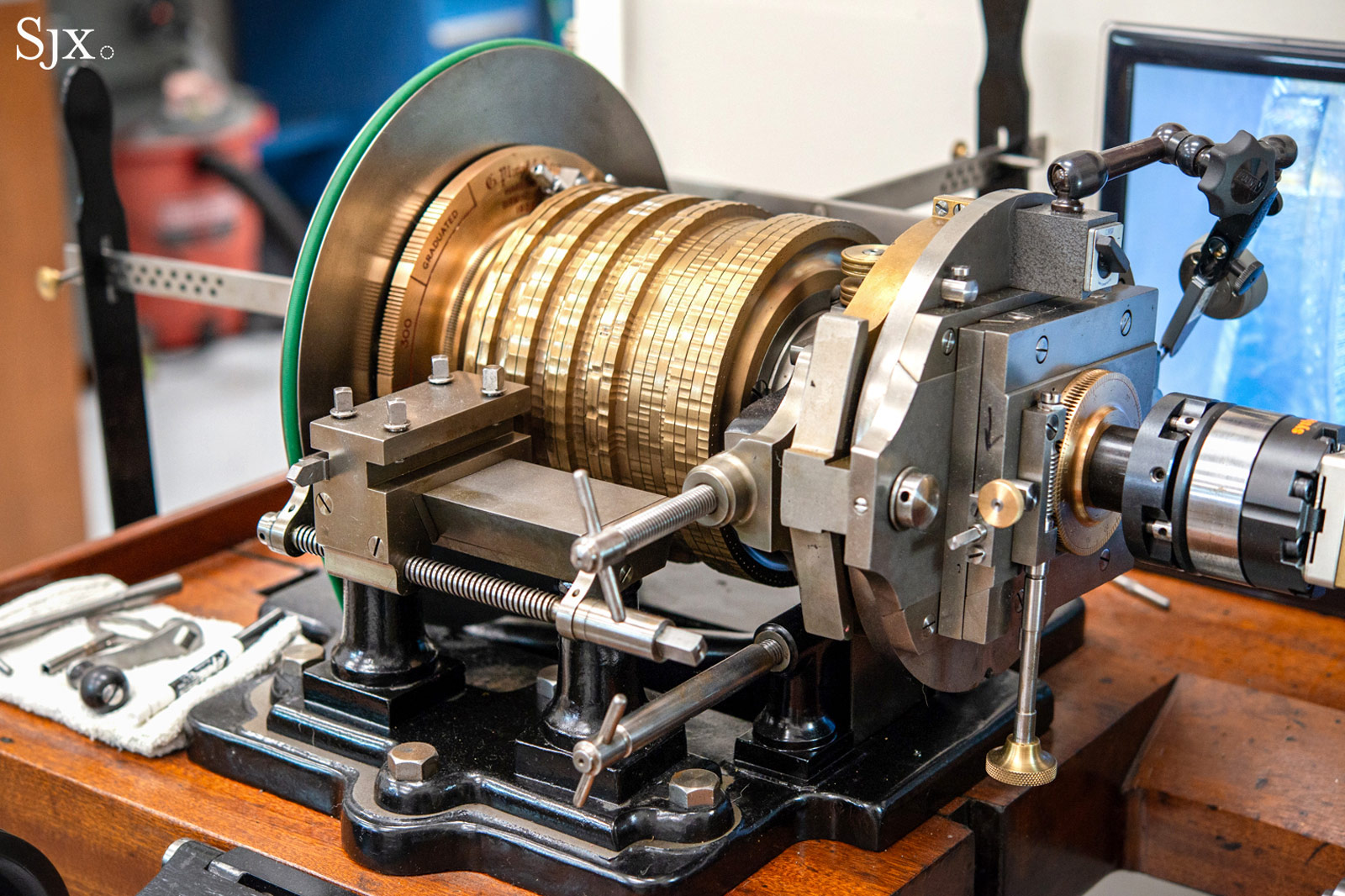

An antique straight-line guilloche engine.

Mr Myrick also makes his own balance wheels in-house, which is quite unusual. Even established independent brands like FP Journe typically source these components from specialist suppliers.

After CNC machining, the balance wheels are poised using an ultrasonic Jema poising tool to ensure they are perfectly balanced.

This device is used to poise balance wheels. An ultrasonic tremor is sent to the wheel, causing the heaviest section to drop to the bottom, where tiny metal shavings are removed to bring it to poise.

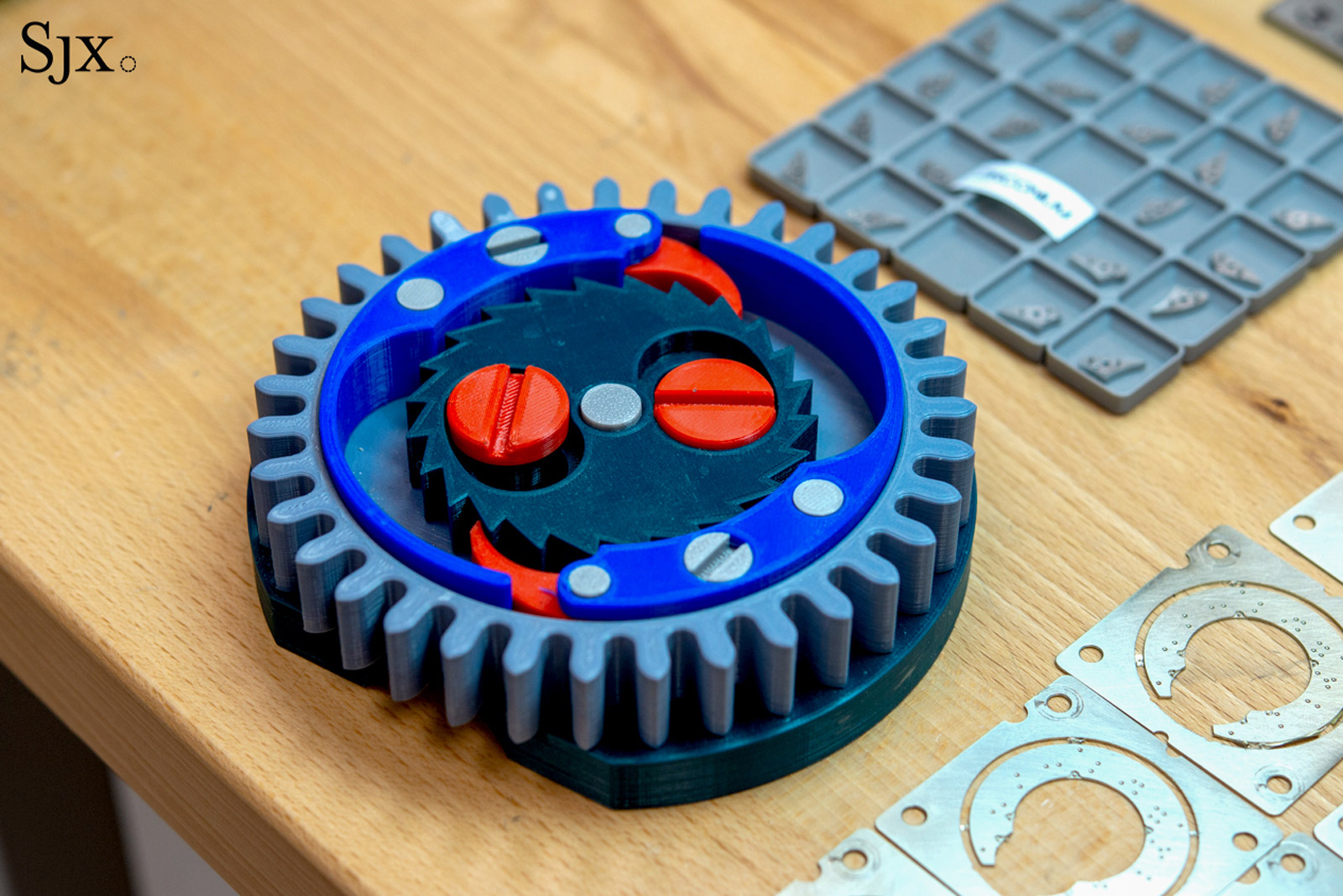

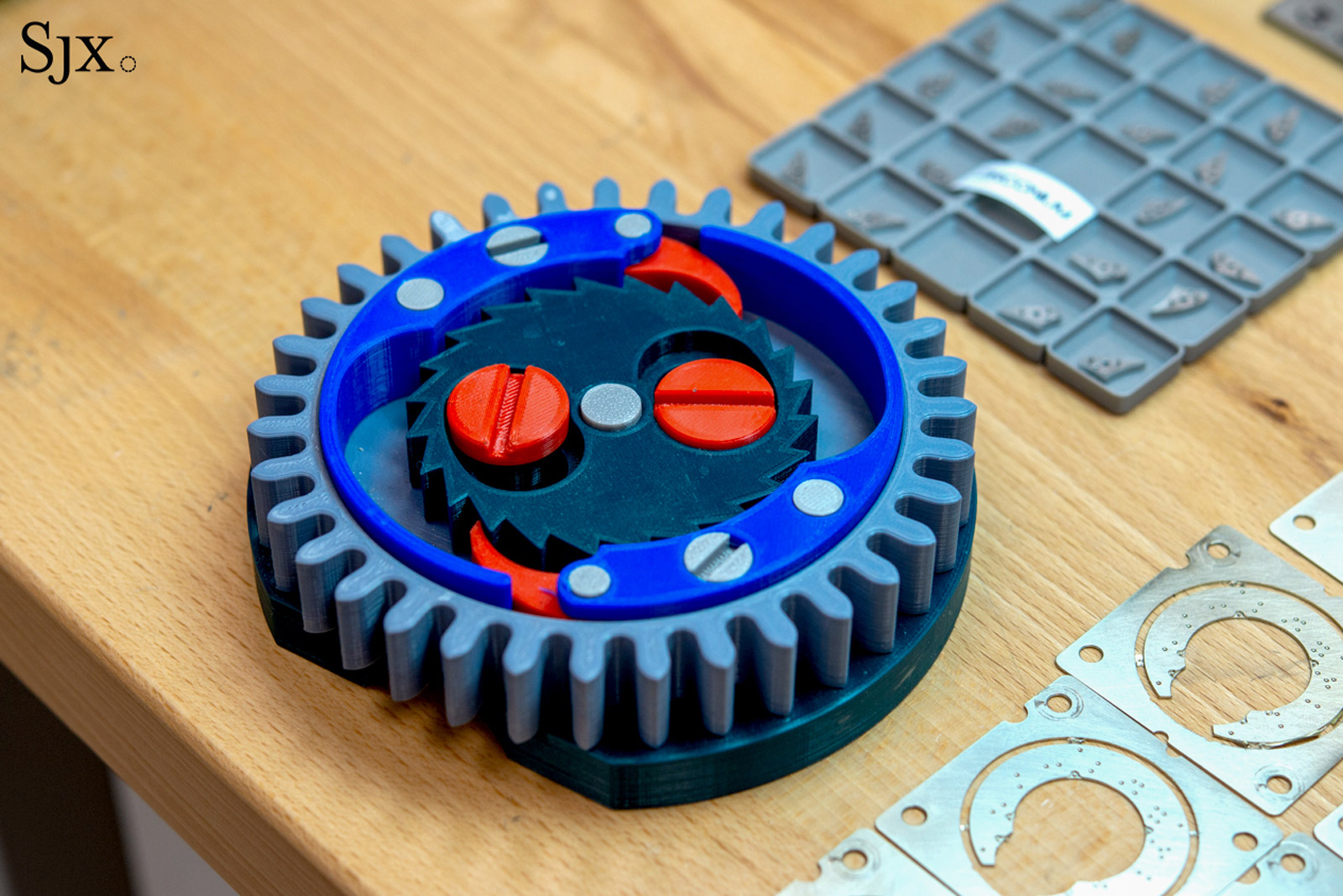

One of the defining technical characteristics of Mr Myrick’s work is his proprietary grande sonnerie-style winding click. A key benefit of his design is that it provides a degree of recoil to protect the mainspring from overwinding. This design required the development of a special hardened steel ‘lift system’ between the mainplate and the three-quarter plate to give clearance over the winding tube, but the chronometric benefits are worth the extra complexity.

Mr Myrick’s proprietary black polished and heat-blued grande sonnerie-style winding click features recoil slots to help protect the mainspring, seen here on an early ‘1 in 30’ piece.

A 3D-printed model of the winding click, with dial blanks crafted from German silver also in view.

The winding click also shows off his skillful application of black polishing, which is likewise apparent on the light and airy balance bridge. It’s rare to see such thin and graceful steelwork, which in some ways reminds me of the work of Voutilainen.

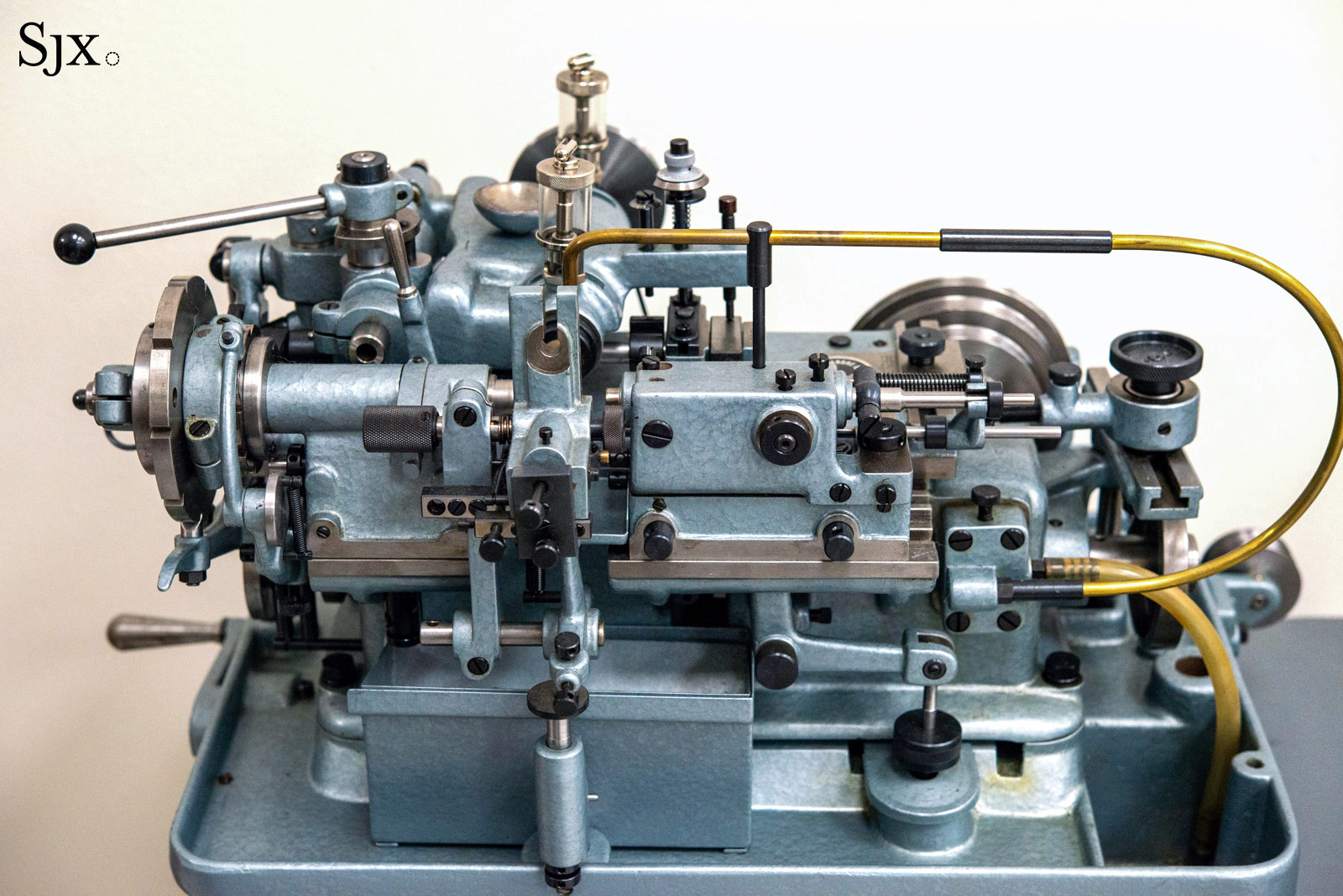

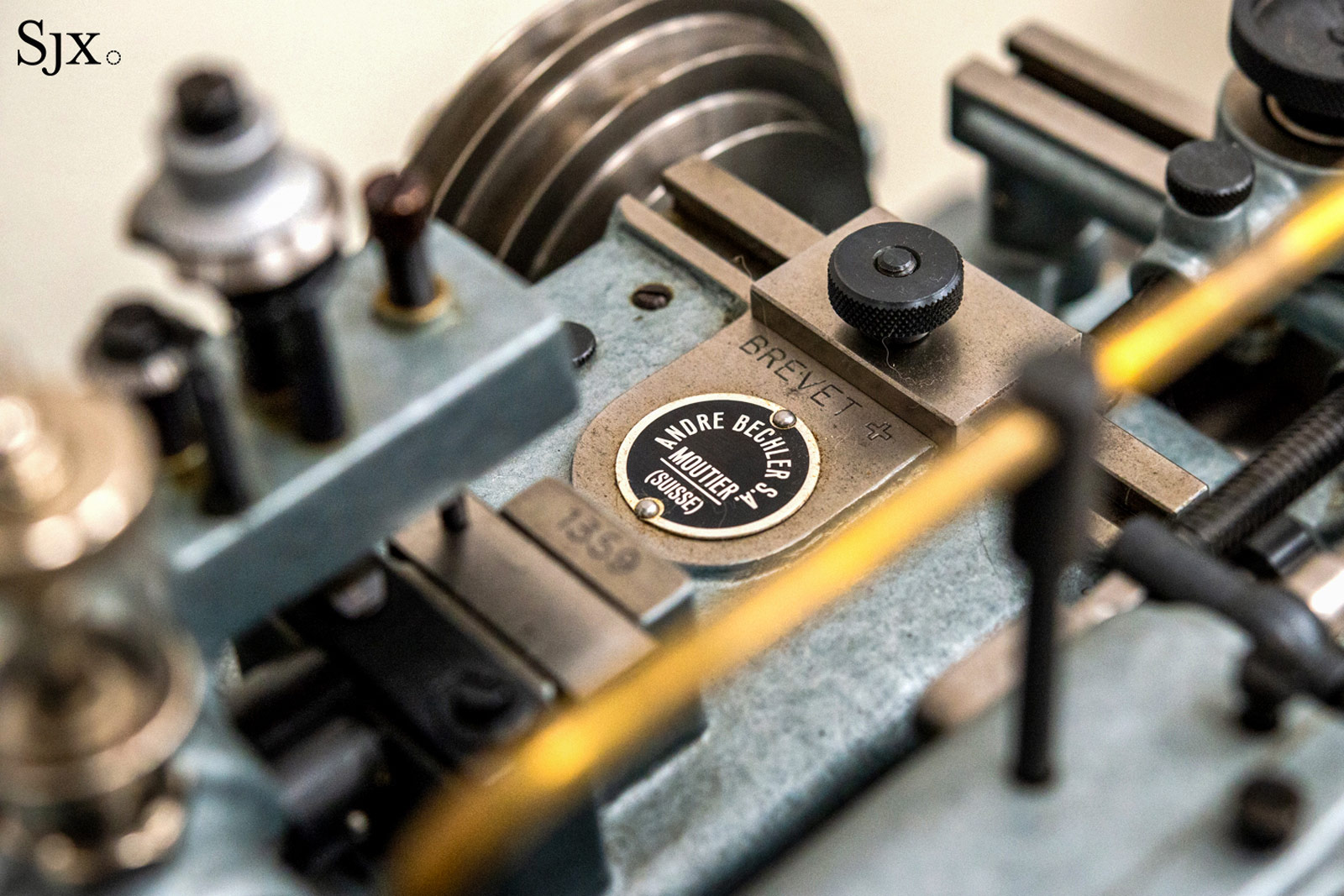

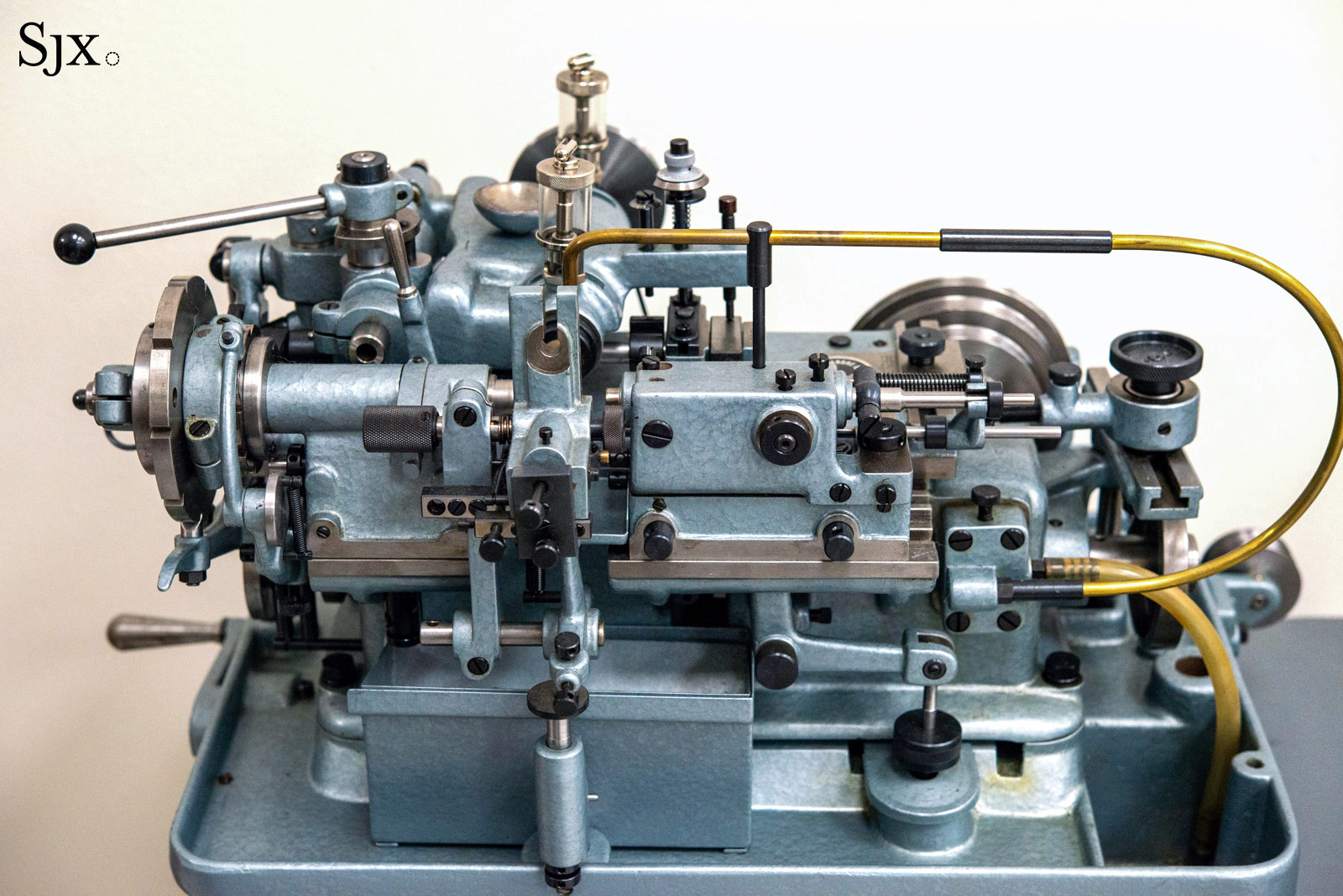

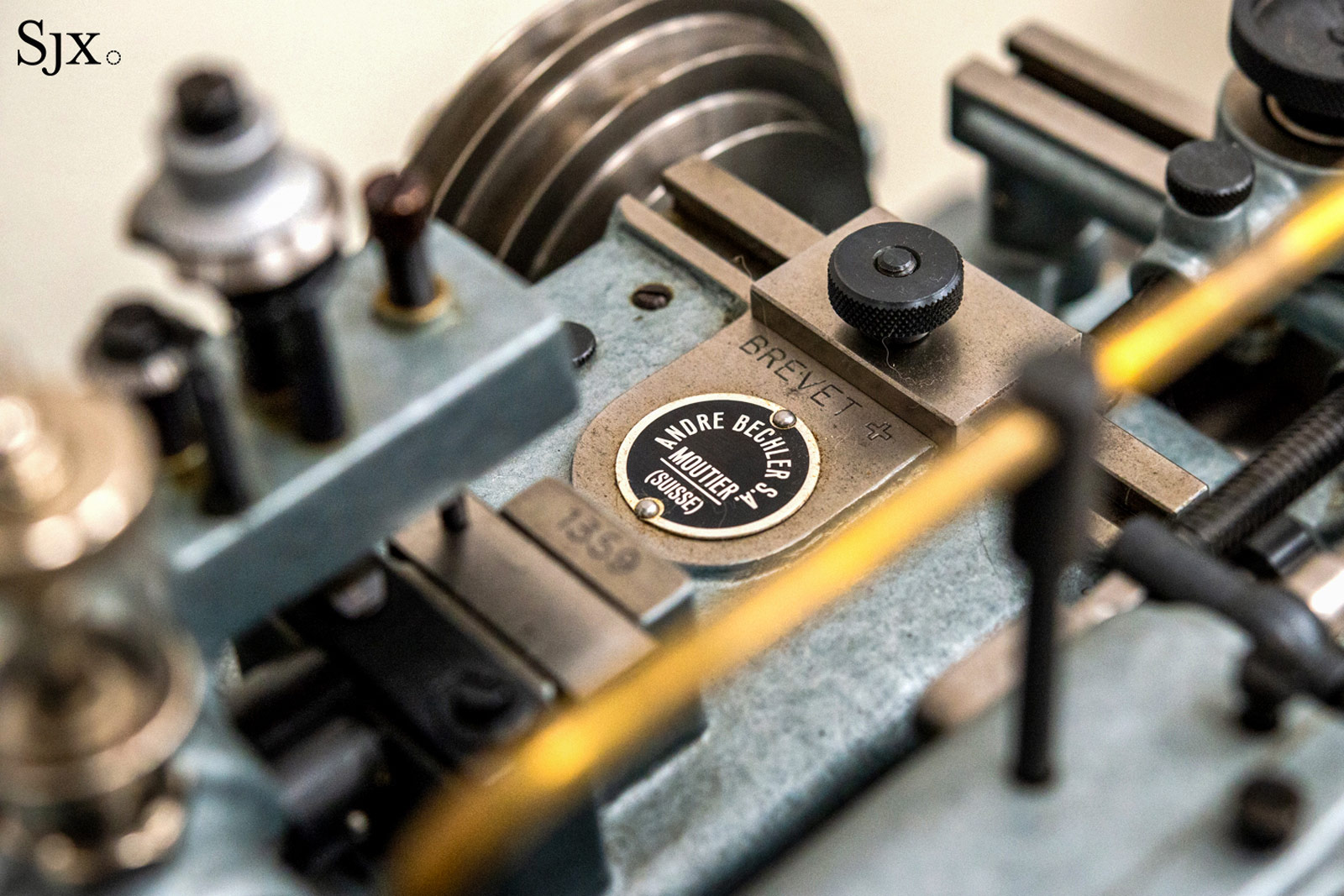

A new old stock Bechler lathe for making pinions.

While early watches used standard cal. 6497 pinions, Mr Myrick has recently invested in a vintage “new old stock” Bechler lathe to produce pinions in-house, so the gear trains are now of his own construction. This machine gives Mr Myrick the ability to control the depth of engagement of the teeth in the gear train, improving the smoothness of energy transmission to the escapement.

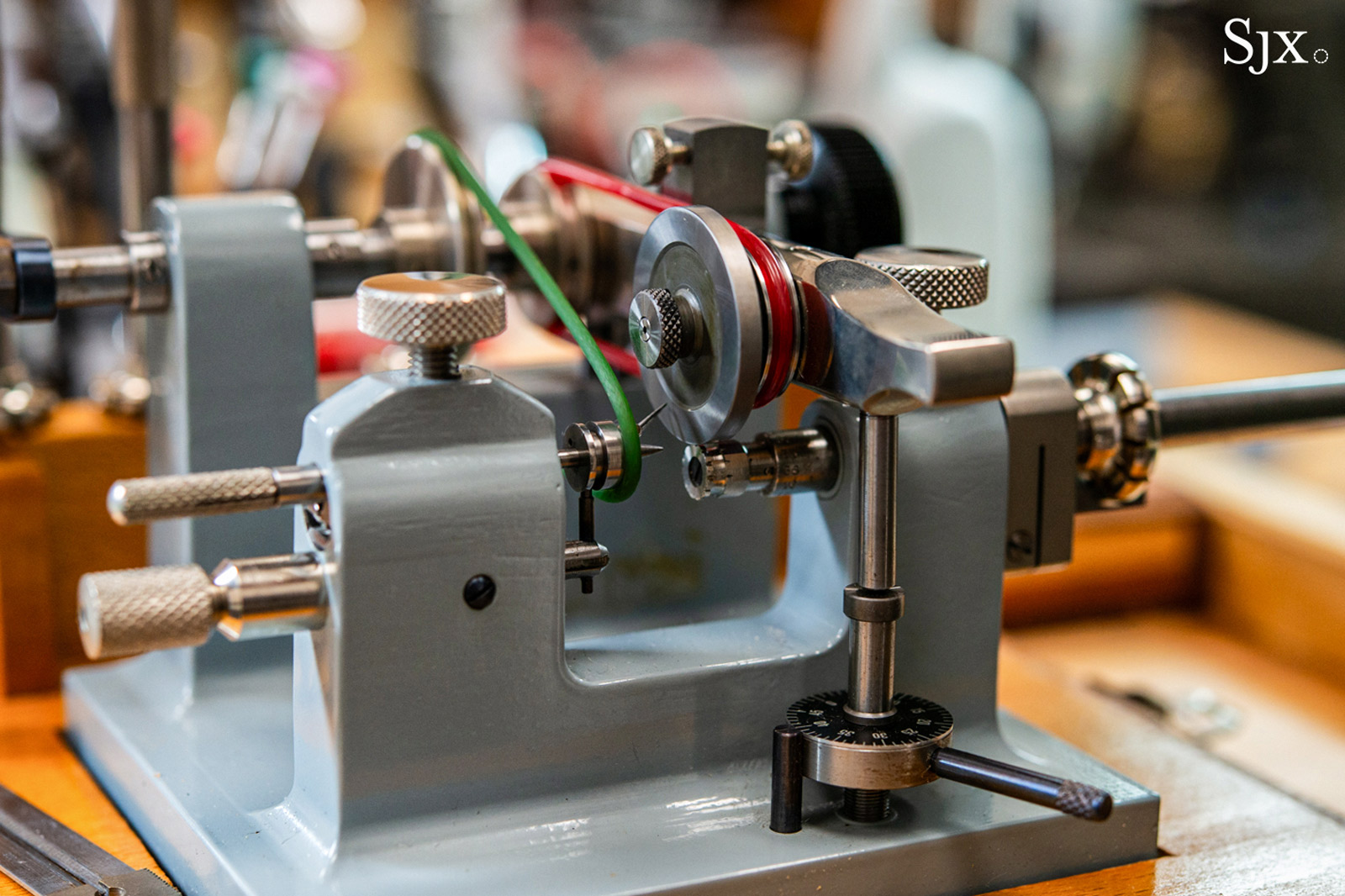

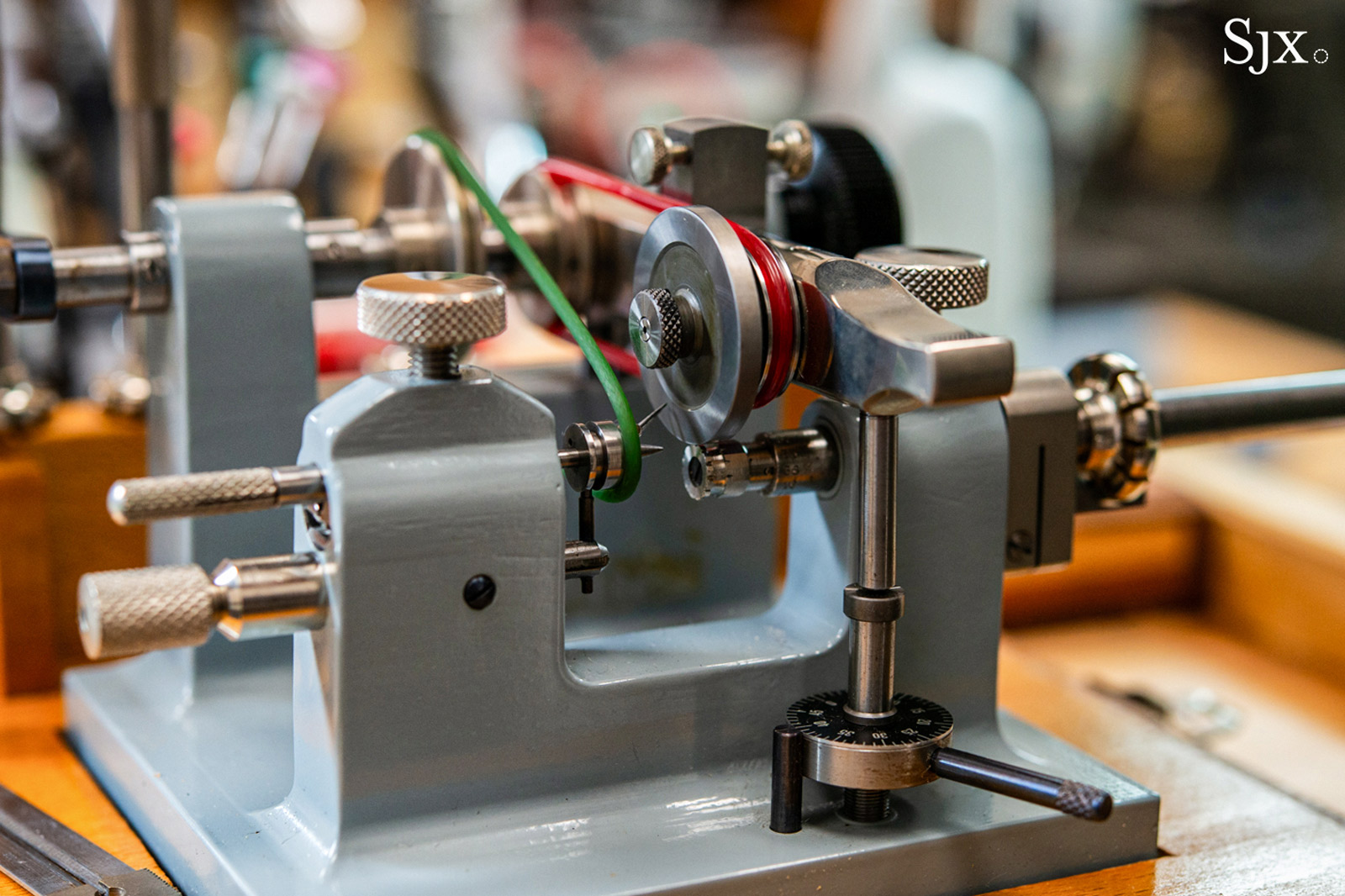

Walking around the workshop, it was refreshing to see so many old-school analogue devices in regular use. For example, Mr Myrick polishes pivots using an antique burnishing tool that enables him to achieve micron-level tolerances to help ensure reliable operation for the (very) long-term.

An antique device used to burnish pivots with micron-level precision.

Dials

Dials and hands are produced entirely in-house, giving clients plenty of latitude for customisation. The materials are mostly traditional: frosted German silver, polished white gold, and polished or heat-blued steel.

The antique rose guilloche engine Mr Myrick uses to hand engrave his zirconium dial plates; note the bespoke headstock that is compatible with the System 3R.

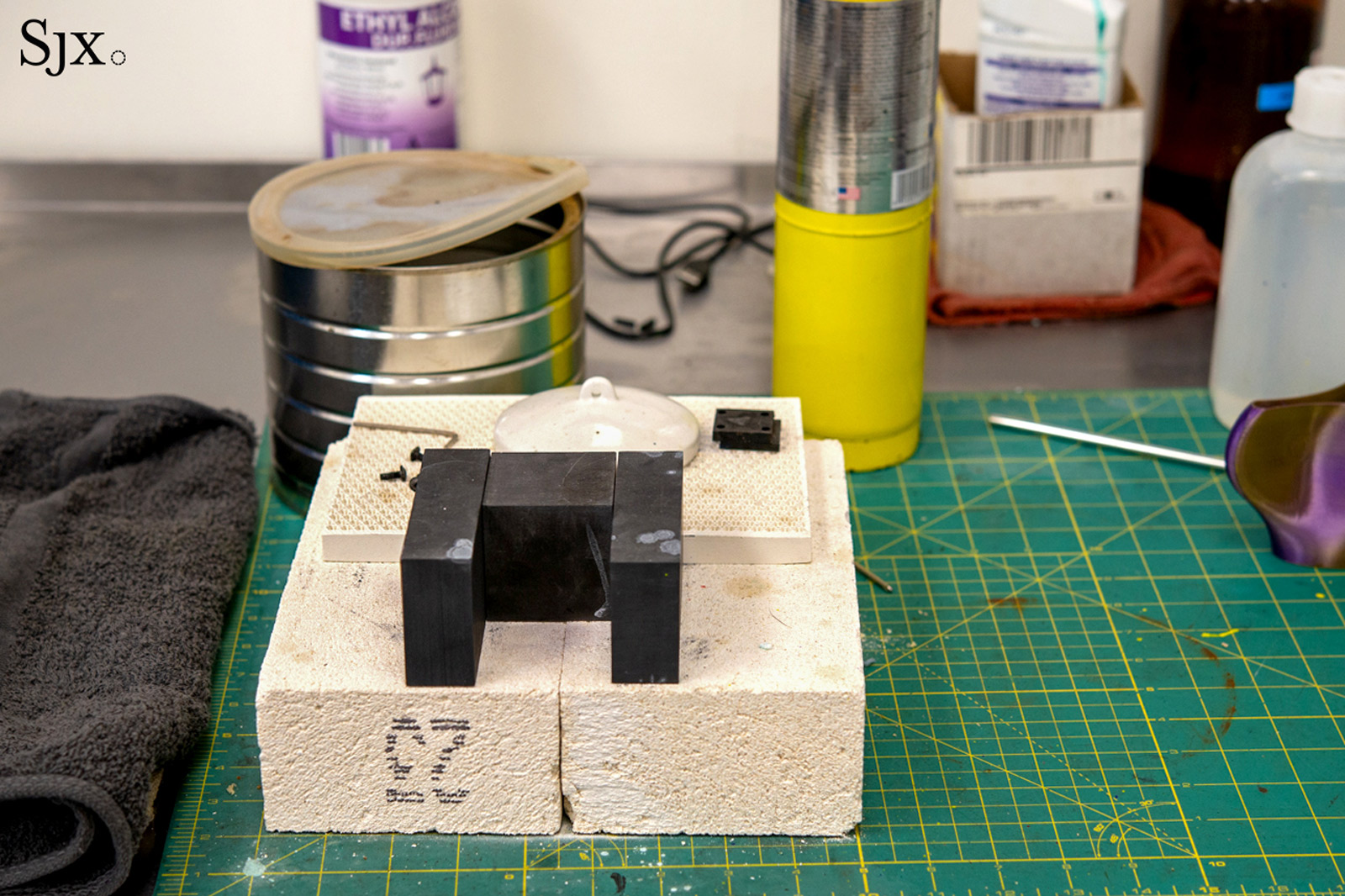

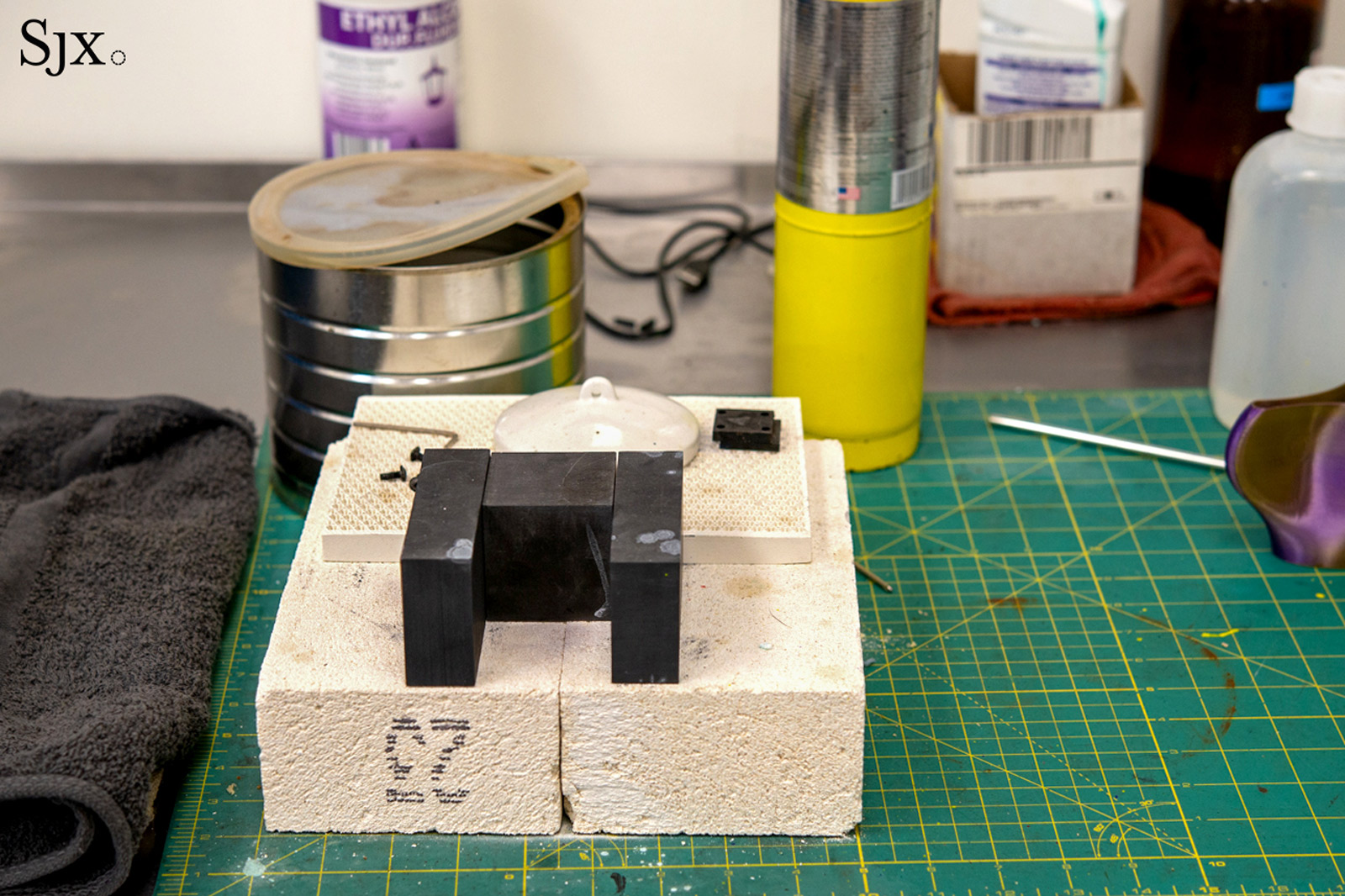

Later pieces in the series feature a heat-blackened zirconium dial plate, hand-turned on a rose engine. Zirconium is a tricky material, chemically unstable in its raw form and prone to warping when heated. Mr Myrick has overcome these challenges using indirect heat to oxidise the material, which gives it a shimmering grey-black coating that helps stabilise the material’s more volatile characteristics.

A heat station for bluing steel and blackening zirconium.

After countless hours researching zirconium, Mr Myrick has learned to love the material and has numerous ideas for using it in his next series.

A later ‘1 in 30’ model with the prototype alongside.

Cases

After his initial case supplier left him stranded, Mr Myrick acquired the tools and know-how to produce cases in-house. Making cases requires an altogether different skill set than that of a watchmaker, which is why case making is often outsourced to specialists.

Mr Myrick CNC-mills his cases from 316L steel and tests each to a pressure of 3 ATM, the industry norm in Switzerland. Despite their simple form, the construction is quite nuanced. For example, to ensure perfectly aligned (and straight) spring bar holes, the lugs are actually drilled all the way through from the outside, and then plugged, welded, and polished. This avoids having to drill the spring bar holes at a slight angle, which is what many brands do when they don’t have the resources to invest in the specialised tooling to drill holes at 90-degrees.

The borders of the state of Oregon are milled into the crown with outstanding precision.

An appealing detail of the later pieces in the One in 30 series is the crown, ‘signed’ with an outline of the state of Oregon. I was surprised to find out Mr Myrick produces this in-house, with a tiny 0.2 mm milling tool, similar to the size required to mill the applied numerals on the dial. The outline is impressively accurate and crisp, which is a testament to the maker’s skill.

The tiny milling tool used to engrave the crown.

Concluding thoughts

While the United States was once an industrial watchmaking powerhouse that forced the Swiss watch industry to modernise, much of that infrastructure, and the reputation that went with it, is gone.

Contemporary American watchmakers like Mr Myrick, Joshua Shapiro, RGM, Nico Cox, Jacob Curtis, and Dewey Vicknair are each doing their part to forge a new reputation for the American watch industry, based on artisanal craft and respect for the past.

Mr Myrick shared some examples from the golden age of American pocket watches. Pieces like this inspire his work.

Mr Myrick’s sense of humour on display.

In other words, in an almost perfect twist of irony, the new generation of American watchmakers is finding relevance by embracing the endangered skills and techniques that the old American watch industry helped make obsolete.

Keaton Myrick is putting his own stamp on this new era of American watchmaking, producing small numbers of handmade watches infused with the independent spirit of the Pacific Northwest.

Updated January 21, 2025: Edited for clarification of the status of the next series of watches.

Back to top.