The two decades or so after the end of the Quartz Crisis was a fruitful one for the mechanical watch industry as it revived itself. IWC was one of the stars of that revival, a highly technical yet niche brand that appealed to true watch nerds. Everything it did then became the foundations for its modern day success – literally, with the brand still relying on the complications invented then.

One of the most interesting, yet little-known IWC watches from that era is the Da Vinci Tourbillon Four Seasons. A limited edition of 20 watches that debuted in 1999, the Four Seasons (or Quattro Stagioni as it was known at the launch) has a hand-engraved, solid-gold dial – the Da Vinci Tourbillon represents the only instance IWC has bestowed such elaborate dials on its watches.

A year after the launch of the Four Seasons, IWC was acquired by Swiss luxury group Richemont, making it perhaps the major complication the brand unveiled before the change of ownership. Intriguingly, the combination of an engraved dial and complicated movement, as well as the style of engraving, brings to mind some of the Handwerkskunst watches by A. Lange & Söhne, then as now, a sister company of IWC.

But perhaps more important is the movement, which is the only hand-wound calibre in this generation of Da Vinci. Not only is the manual-wind calibre better looking – by a massive margin – but the movement is descended from the Il Destriero Scafusia, the grand complication made for the brand’s 125th anniversary in 1993.

The Da Vinci Tourbillon Four Seasons – one of the 20 is on show at the Beyer Watch & Clock Museum owned by the famous Zurich watch retailer

Kurt Klaus’ bestseller

Though substantially under appreciated now – for a variety of reasons, more on those late – the Da Vinci is an important watch, both for IWC and modern watchmaking.

When the Da Vinci ref. 3750 was unveiled in 1985, it was the first self-winding chronograph with perpetual calendar. And more importantly, it was one of the handful of highly complicated watches on the market, which was then sparse being just a few years out of the Quartz Crisis. It was a hit for IWC, which made a lot of them, explaining why they are still common long after being discontinued.

The original Da Vinci ref. 3750 of 1985. Photo – IWC

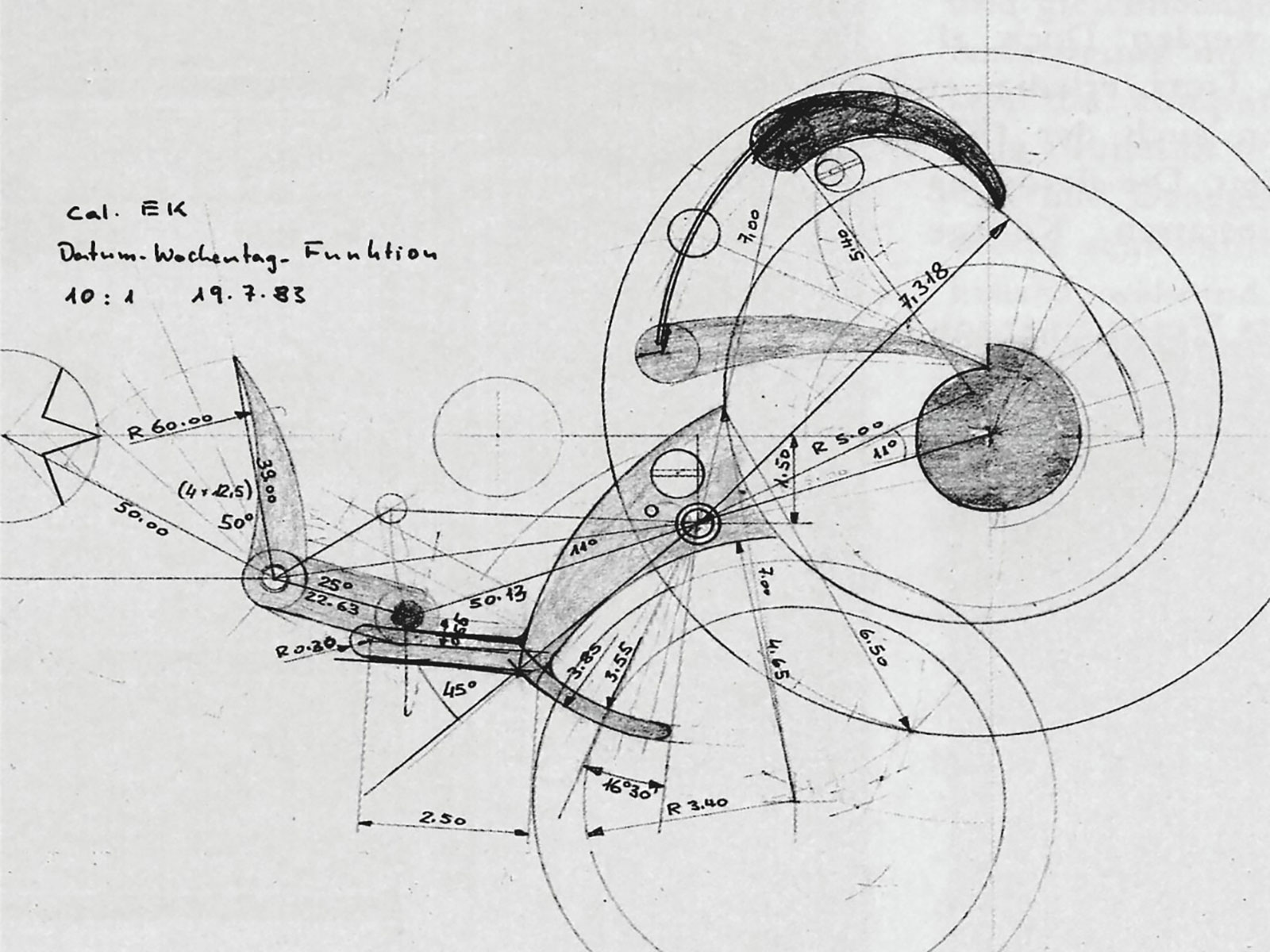

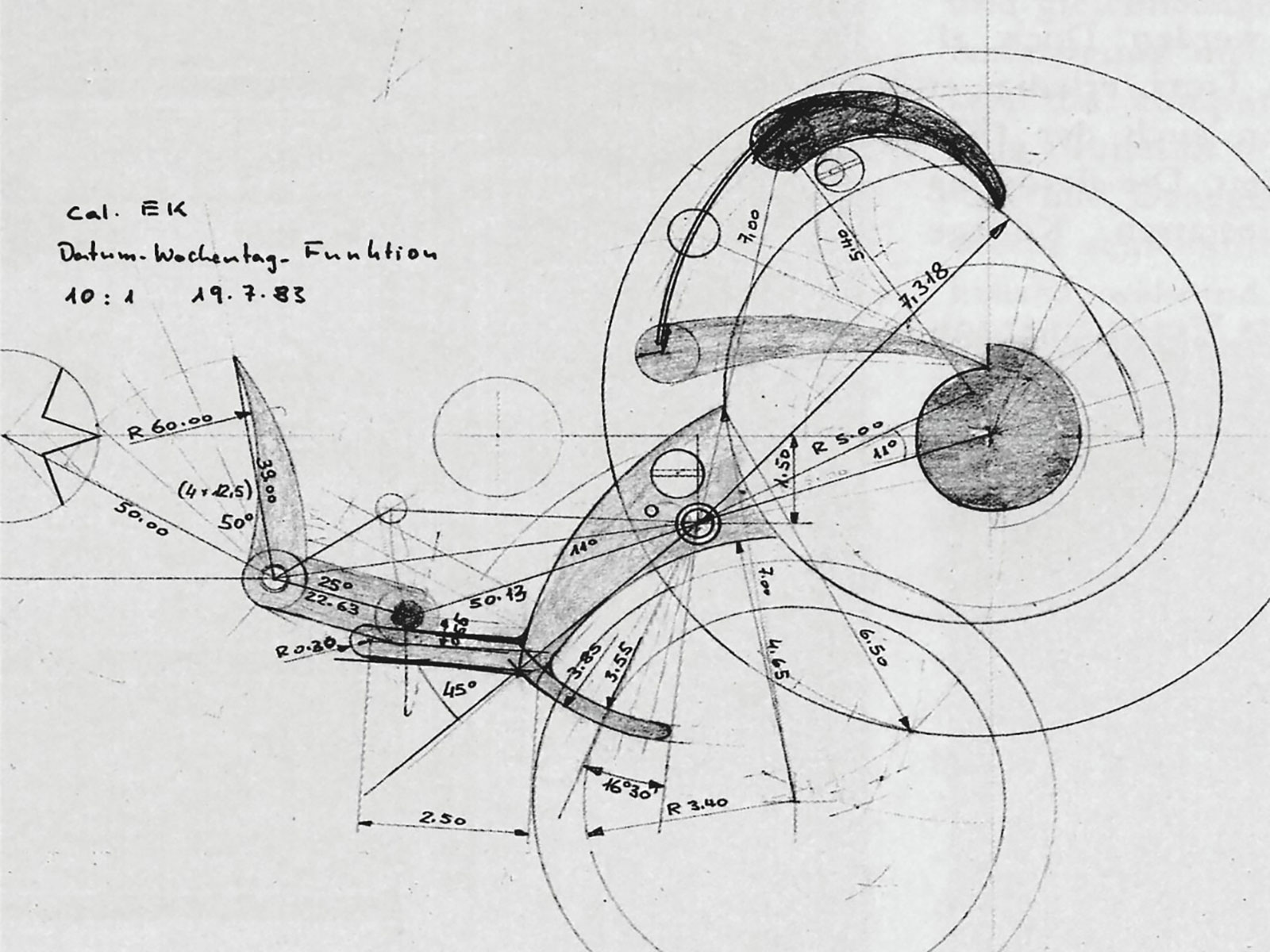

The genius behind the Da Vinci ref. 3750 was not the chronograph, but the perpetual calendar conceived by IWC’s veteran technical chief Kurt Klaus. Developed to be user-friendly and efficient to assemble – the opposite of all perpetual calendar mechanisms till then – Mr Klaus’ calendar module was made up of just 81 parts.

Despite the brevity of construction, the calendar was comprehensive. In a first for wristwatches, the calendar included a four-digit year year, perhaps pointless from a practical perspective but a functional memento mori that serves as a reminder the calendar will long outlive everyone.

All the calendar indications were synchronised at the factory and could only be set forwards via the crown, a great convenience to the wearer, so long as the calendar was not set beyond the current date. Going backwards on the required a trip to the service centre, making the unidirectional setting was a compromise, but a sound and reasonable one. The calendar is robust and practical, which is why IWC still utilises the same mechanism today.

It was installed on a Valjoux 7750 base – Mr Klaus told me the movement was ideal due to its stable and substantial torque – to create the cal. 7906 in the original Da Vinci ref. 3750. (The movement was subsequently improved and evolved into the cal. 79061 and then cal. 79261, though the basics remained unchanged.)

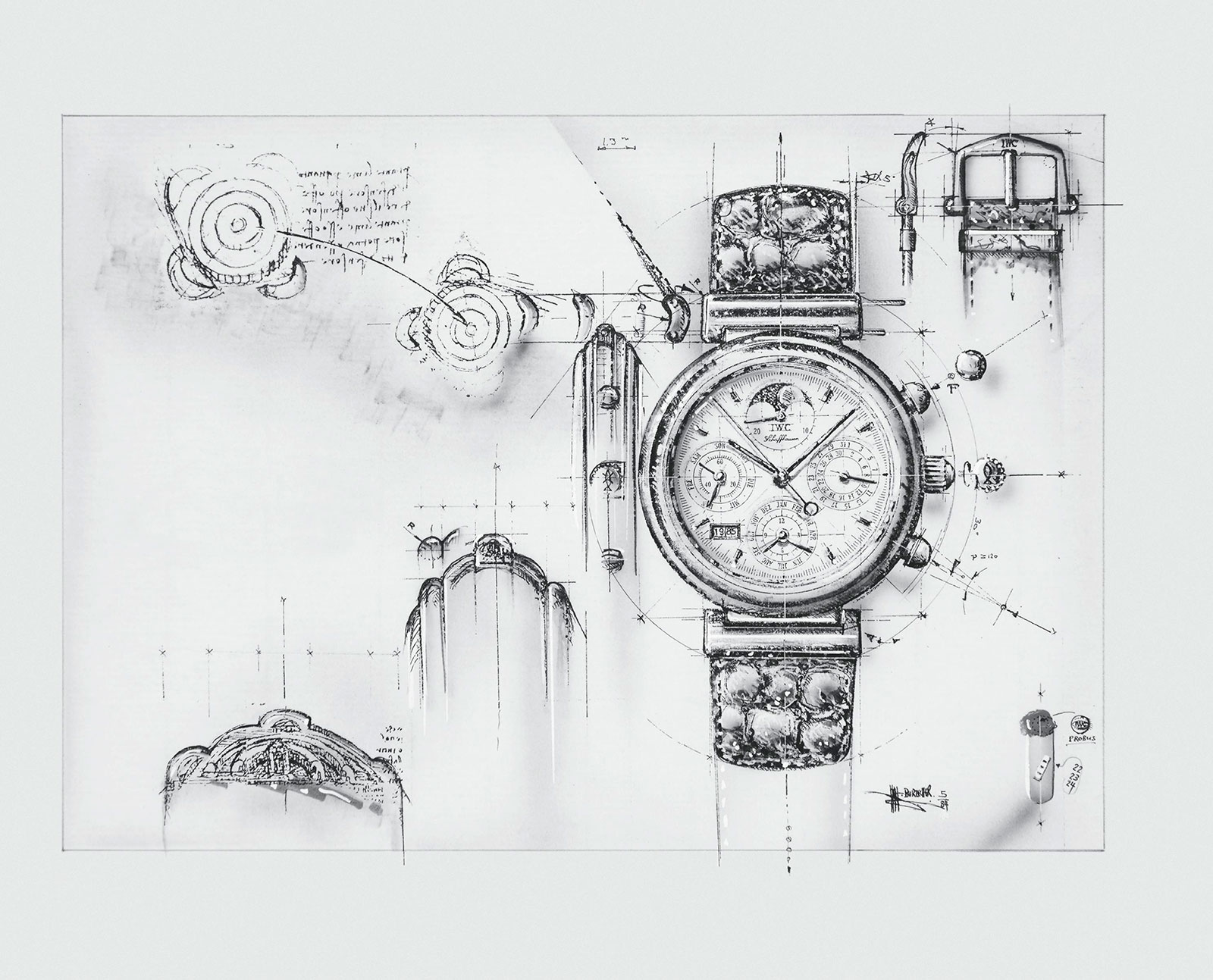

The 1983 sketch for the “Cal. EK”, short for ‘ewiger kalender’, German for “perpetual calendar”. Photo – IWC

While Mr Klaus’ role in developing the Da Vinci is well publicised, the man responsible for the simple-yet-recognisable case is less known.

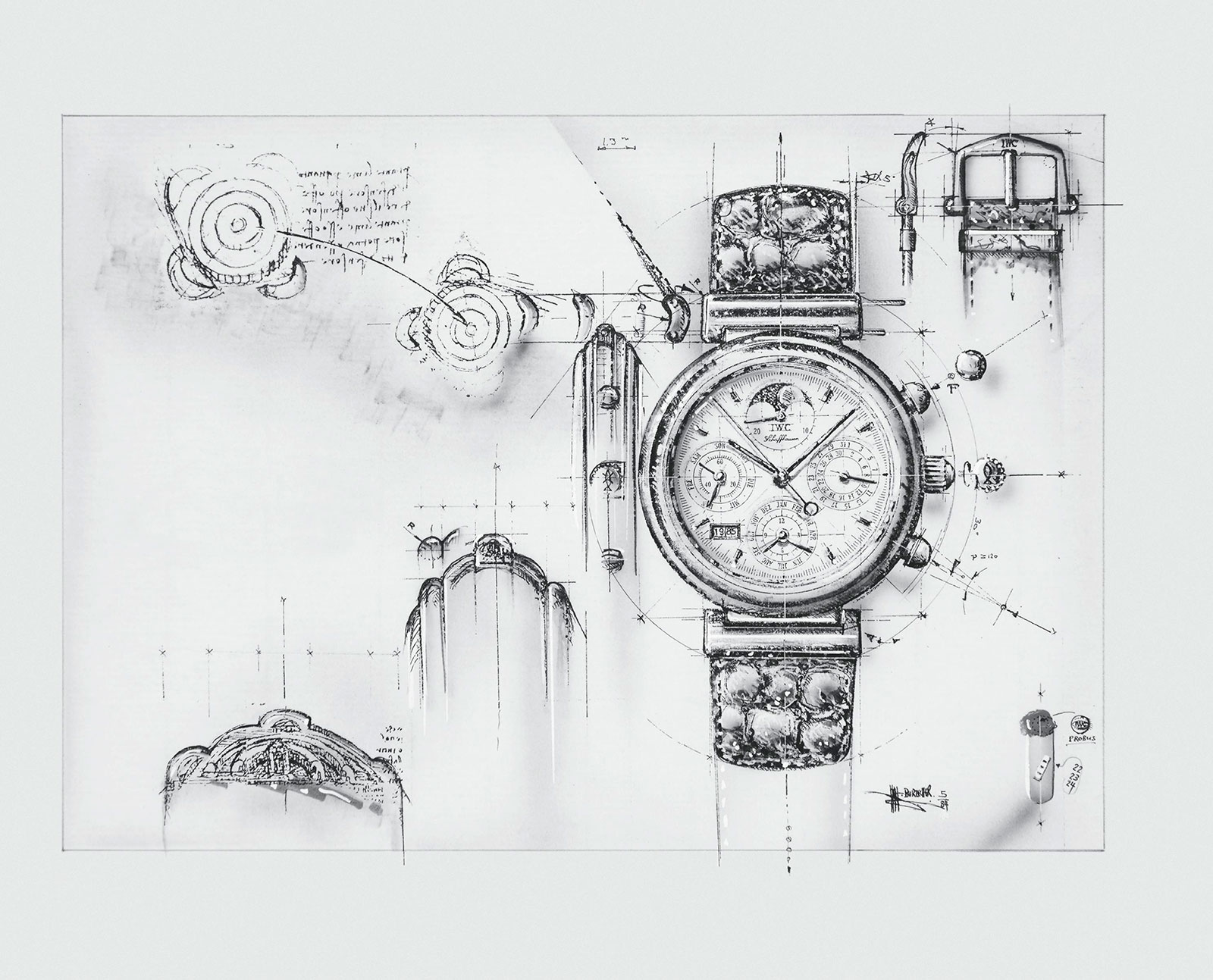

Hanno Burtscher, then the brand’s chief designer, formed the Da Vinci case after being inspired by sketches Leonardo Da Vinci had made for a fort, which were in turn inspired by the real-life Fortress of Piombino. When viewed from the side, the thick case of the Da Vinci reveals sloping, stacked layers that do indeed bring to mind a medieval fort.

As for the bar-type or “Vendome” lugs, legend has it Mr Burtscher encountered similar lugs on a vintage IWC watch, and put them together with his castle-inspired case. But a more prosaic explanation could simply have been the popularity of this design in the 1980s, with successful brands of the era like Cartier and Gerald Genta being leading proponents of the style. So the Da Vinci does look very much like a 1980s watch, making it either dated or classic, depending on whether you like it.

Hanno Burtscher’s sketch for the Da Vinci. Photo – IWC

Growing the family

In 1995, IWC celebrated the tenth anniversary of the original ref. 3750 with the Da Vinci Perpetual Rattrapante ref. 3751, which added a split-seconds chronograph – appropriately adding a tenth hand to the dial. Even with the added complications, all the variants of the original Da Vinci retained the same 39 mm case of 1985. Not only was it too small for contemporary tastes by the late 1990s, the thickness of the case made gave it a burger-like profile.

And so in 2000 IWC unveiled the ref. 3754, the split-seconds Da Vinci in a 41.5 mm case. The case was enlarged, but retained the same design. Just as importantly, it was upgraded with a sapphire crystal, replacing the Plexiglas of the earlier generation, something out of place on a luxury watch by then. In 2004, the same facelift was applied to the base-model Da Vinci, and it too got a 41.5 mm case along with a sapphire crystal, becoming the ref. 3758.

The upsized models did not just get a new case and crystal, but are also set apart by a different dial that has large Arabic numerals and wide, lance-shaped hands hands. While doubtlessly an attempt to modernise the old-school Da Vinci dial, the redesigned dial lost the elegant simplicity of the original, and ironically appears more cluttered, even though the calendar sub-dials were streamlined.

The Da Vinci Rattrapante ref. 3754 with the enlarged, 41.5 mm case. Photo – Sotheby’s

But the focus of this story is the Da Vinci Tourbillon ref. 3752, unveiled in 1999 to mark the new millennium – and fortunately fitted with the original Da Vinci dial.

Limited to 50 in platinum and 200 in yellow gold, the Da Vinci Tourbillon was essentially indistinguishable from the base-model Da Vinci, with the only giveaway being “Tourbillon” in between four and five o’clock.

More special were the Da Vinci Tourbillon models with engraved dials. Launched the same year was the Da Vinci Quattro Stagioni, Italian for “four seasons”. And then in 2002, 150 pieces of the Da Vinci Tourbillon Leonardo were produced, with 50 in each colour of gold, though I doubt the 150-piece run was completed as they are infrequently encountered. Made to mark the 550th anniversary of Leonardo Da Vinci’s birth, the Tourbillon Leonardo featured a bust of the artist and his inventions on the dial.

A little over a year after the launch of the Four Seasons, IWC’s then-parent company, Les Manufactures Horlogères (LMH), was taken over by Richemont. Along with IWC, the Swiss group also took control of A. Lange & Söhne and Jaeger-LeCoultre. Since then, IWC has not made anything like the Four Seasons, no doubt to leave this particular segment to its sister brands.

The Da Vinci Tourbillon ref. 3752 in its simplest guise. Photo – Sotheby’s

Das tourbillon von IWC

Unlike the Da Vinci variants equipped with automatic movements based on the Valjoux 7750, the Da Vinci Tourbillon is powered by the hand-wound cal. 76061 that’s built on the Valjoux 7760. And the movement traces its lineage back to IWC’s Il Destriero Scafusia uber-complication.

Hand-wound movements bring the wearer a little closer to the life inside a watch, and are naturally more traditional. Being hand-wound elevates the Da Vinci Tourbillon to a slightly more refined realm of complications, despite the humble base movement. And the model was also produced in far fewer numbers than the other Da Vinci variants – which are perhaps too common – making the tourbillon edition slightly more special.

The cal. 76061

More importantly – and very obviously – the cal. 76061 looks entirely different from the self-winding Da Vinci movements, which are not very appealing since they look similar to the stock 7750, explaining why the automatic models all have solid backs. Perhaps because the Da Vinci Tourbillon has a display back, the finishing of the cal. 76061 is a cut above the usual IWC decoration. It’s still workmanlike, but attractive nonetheless.

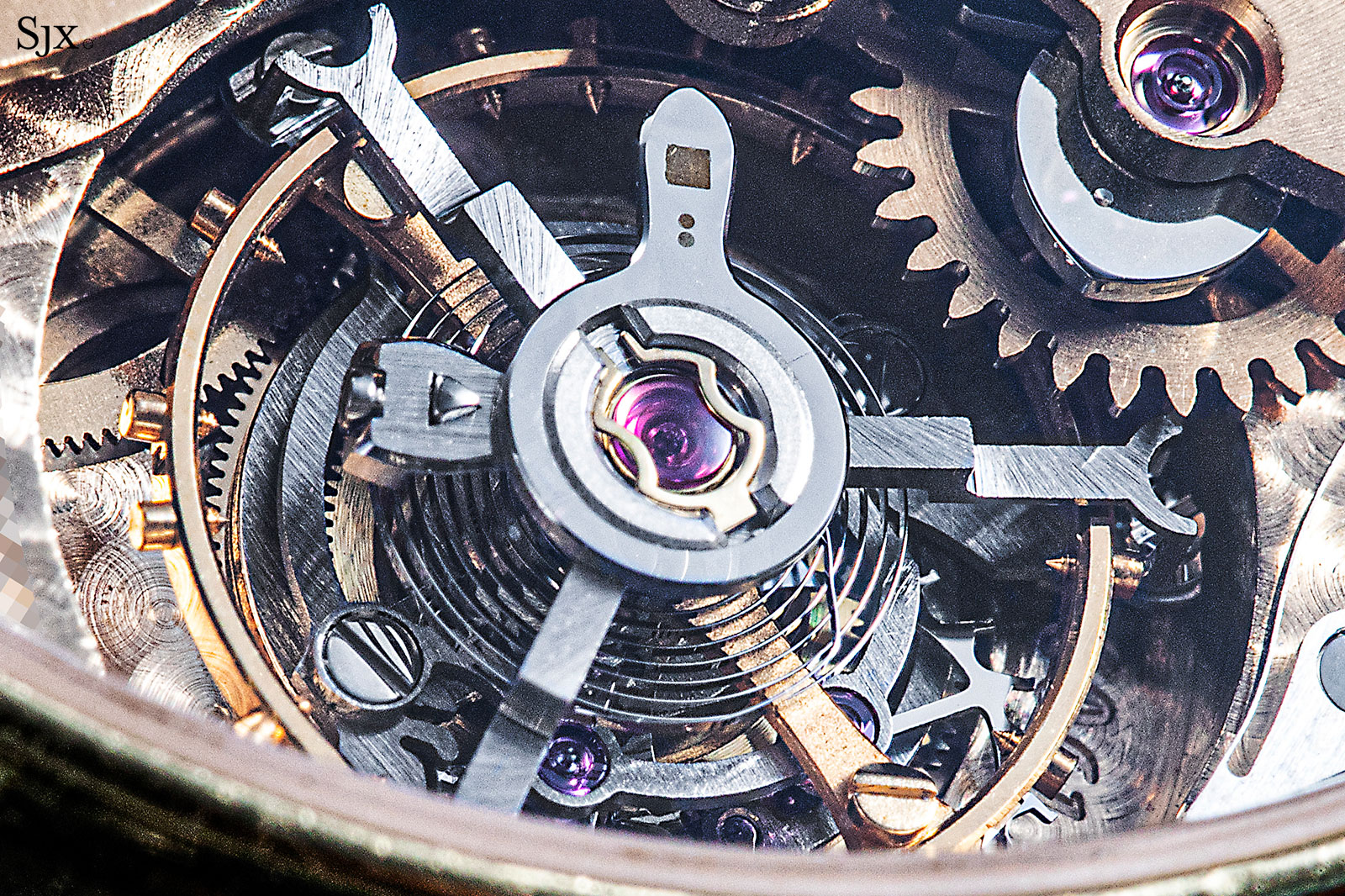

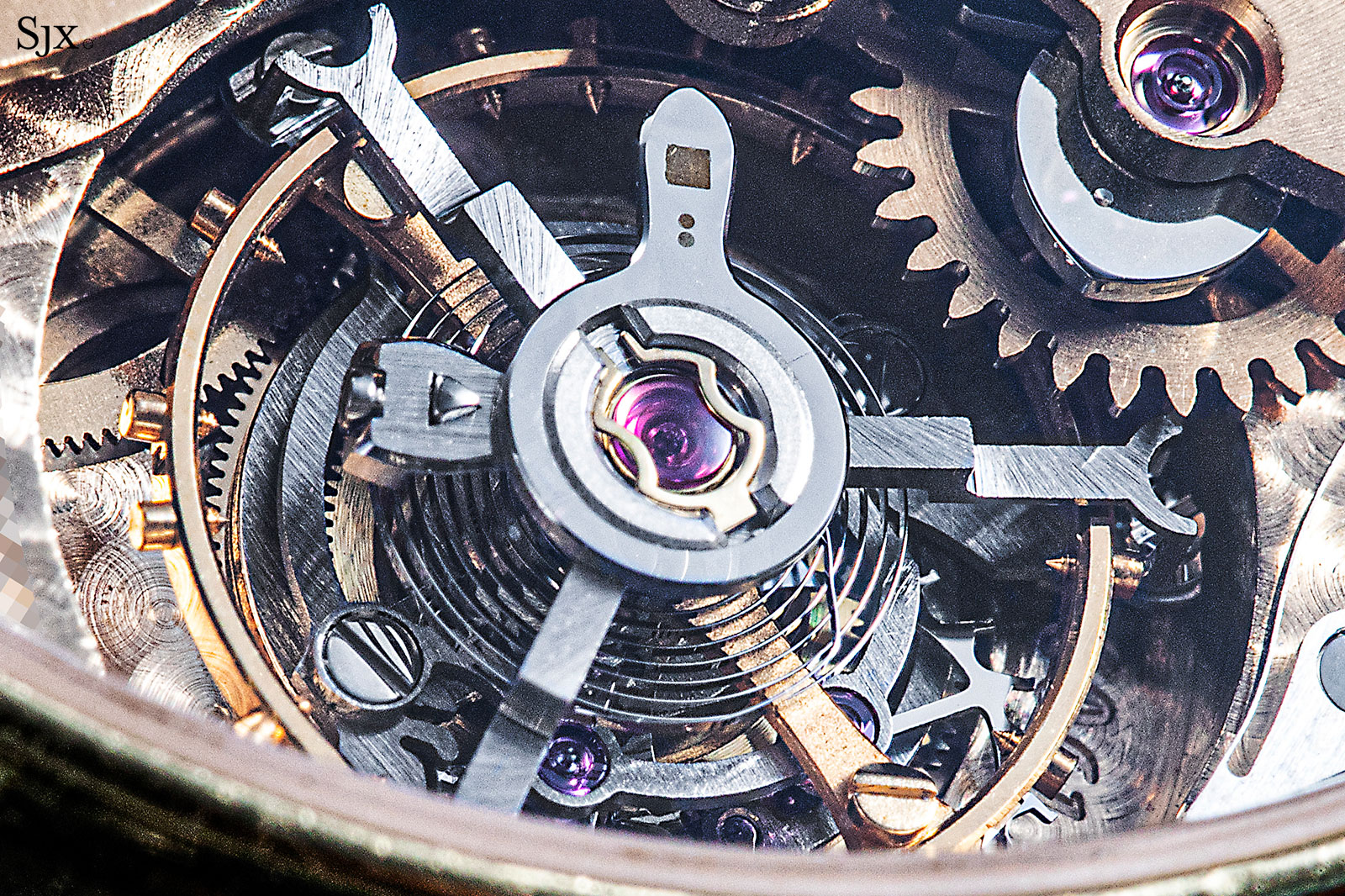

With the cal. 76061, the recognisable 7750 architecture of the automatic Da Vinci gives way to something more unusual, one that is not instantly recognisable as a Valjoux. There are a couple of visible hints that reveal the Valjoux chronograph origins, including visible wire springs and the oscillating pinion that’s a trademark of the movement. But that’s well camouflaged, with the movement dominated by a gracefully-curved, three-quarter plate that reveals the flying tourbillon.

Within the large plate is a whimsical yet practical detail: a little recess that accommodates the centuries slide for the year display of the calendar that will be required for the years 2200 till 2499. In the original Da Vinci, the centuries slide is stored in a waxed-sealed glass vial that’s easy to lose.

A long wait to use it

The flying tourbillon inside the Da Vinci Tourbillon is fundamentally the same construction that IWC still uses today, including in the recent Portugieser Perpetual Calendar Tourbillon Edition “150 Years”.

Its origins lie in a compact flying tourbillon invented by Austrian watchmaker Richard Habring in 1991, a year after he joined IWC. Richard had already built a flying tourbillon regulator two years earlier before he joined the brand – it was larger and installed in a table clock – but the 1991 tourbillon made a big stride forward by replacing the pivots of the cage and escape wheel with ball bearings. The result was a tourbillon that was both more robust and easier to put together.

He then refined his idea over the next two years, giving it a three-armed titanium cage while perfecting the tourbillon regulator as a module that could be installed whole into a movement. The lightweight, compact and high performance tourbillon was then installed in the cal. 18680 of Il Destriero Scafusia.

The tourbillon inside the Da Vinci Tourbillon is practically identical to that in Il Destriero Scafusia. Though radical in its day, the tourbillon features traditional details like a Breguet overcoil hairspring as well as an adjustable-mass balance with 18 screws on the rim and two weights on the arms.

The flying tourbillon invented by Richard Habring

As the identical tourbillons reveal, the cal. 76061 of the Da Vinci Tourbillon is a simplified version of the cal. 18680 in Il Destriero Scafusia, essentially the calibre sans split-seconds and minute repeater. The visual similarity between the two makes the shared heritage obvious.

The three-quarter plates on both are nearly identical, both revealing the heart-shaped reset cam for the chronograph as well as a section of the chronograph levers. Even the serial numbers are engraved on exactly the same spot on the base plate.

The cal. 76061 of the Da Vinci Tourbillon

The cal. 18680 of Il Destriero Scafusia

Quattro Stagioni

Of the several versions of the Da Vinci Tourbillon, the Four Seasons is the standout, quite literally. The inspiration for the watch reputedly came from a customised Da Vinci made in the early 1990s for a European client, whose timepiece featured a gold dial engraved with an allegorical motif. That one-off watch formed the genesis of the Four Seasons, reputedly created at the suggestion of IWC’s Italian distributor at the time, hence the initial model name of Quattro Stagioni.

In every respect the Four Seasons is identical to the standard model, except for the dial. But the dial is the element that completes the watch. While the standard Da Vinci Tourbillon has a brilliant and appealing movement, it is let down by a pedestrian dial.

Made of solid gold, the Four Seasons hand was hand engraved by Wolfgang Siegwart, then the chief engraver at IWC; since Mr Siegwart retired, IWC no longer decorates its watches with hand engraving. Mr Siegwart’s most recognisable work is likely the hand-engraved cursive script on the case back of every IWC Grande Complication, but his best work is probably the Four Seasons dial.

Baroque and slightly ornate for today’s taste, the dial is rendered in intricate detail and shines on the wrist. Four figures are depicted in a stylised and slightly Art Nouveau manner, each representing one of the seasons. Spring, for instance is at 10 o’clock with a bouquet of flowers, while autumn holding a goblet is at five o’clock.

The allegorical motif is inspired by the Classical Greek and subsequently Roman depictions of goddesses of the seasons known as Horae. The four figures sit against a granular background reminiscent of the tremblage engraving found on several Handwerkskunst limited editions of A. Lange & Söhne.

The seasons (clockwise from top left): spring, summer, autumn, and winter

The figure of autumn at four o’clock

Less obvious but equally impressive is the minute track on the periphery of the dial, which is made up of raised hashmarks. Though the hashmarks are of alternating lengths to help legibility, reading the exact minutes is still near impossible.

The moon phase disc is sparkling aventurine glass

Because the calendar was available in several languages, each of the sub-dials are separate discs that can be swapped

Concluding thoughts

I like most variants of the 1985 Da Vinci – the complications are smartly constructed and they are a tremendous value proposition today. IWC made a lot of them, so they aren’t rare watches and are regularly encountered on the secondary market, but they are still good watches by all intrinsic parameters.

Still, the value proposition does come with a couple of caveats. The most obvious is a problem common to all perpetual calendars with the calendar in sub-dials – legibility is average at best, and usually poor when it comes to the tightly packed numbers of the date register.

Another is the smallish, 39 mm case and dinky Plexiglas of the original generation. Though the later, 41.5 mm models fix both of that, the dial on the enlarged Da Vinci doesn’t work with the design.

And then there are the lugs, probably the biggest obstacle for most. The swivel lugs are the element that give the case a dated look. And they also create a silhouette on the wrist that takes some getting used to. But the lugs grow on you, as they have on me. They also wear surprisingly well thanks to the hinged joint. The only drawback is practical: the metallic clink when the lugs swivel.

Because all of the Da Vinci watches look so similar, it is difficult to distinguish them, but any one of the many variants is tremendous value in terms of complication for the dollar.

The standout of the lot, both in terms of technical interest and value, is the Da Vinci Tourbillon. An example of a Da Vinci Four Seasons sold at Sotheby’s Geneva in November 2018 for just 27,500 Swiss francs, while the versions without the engraved dials are usually available for a third less.

That said, the simpler models, namely the base model ref. 3750 and the split-seconds, are typically even more affordable, and perhaps the best value if you find the tourbillon superfluous.

Back to top.