In-Depth: The Unfinished George Daniels Watch

Tourbillon, remontoir, and co-axial.

George Daniels’ contributions to horology, as a watchmaker, historian and educator, were multi-dimensional. Most are widely known, and his watches are now incredibly valuable. But one of his creations – the “Unfinished Daniels” – remains tantalisingly incomplete, residing in the Clockmakers’ Museum within London’s Science Museum (which is also now home to Daniels’ Space Traveller II pocket watch).

Even though he completed only a small number of watches – 23 pocket watches and four wristwatches made by hand, along with the serially-produced Millennium watches – Daniels’ inventions, techniques and philosophy have been deeply influential. His successor Roger W. Smith now practices the Daniels method with his own hand-made watches, but other notable watchmakers, including Francois-Paul Journe, have cited Daniels as an inspiration.

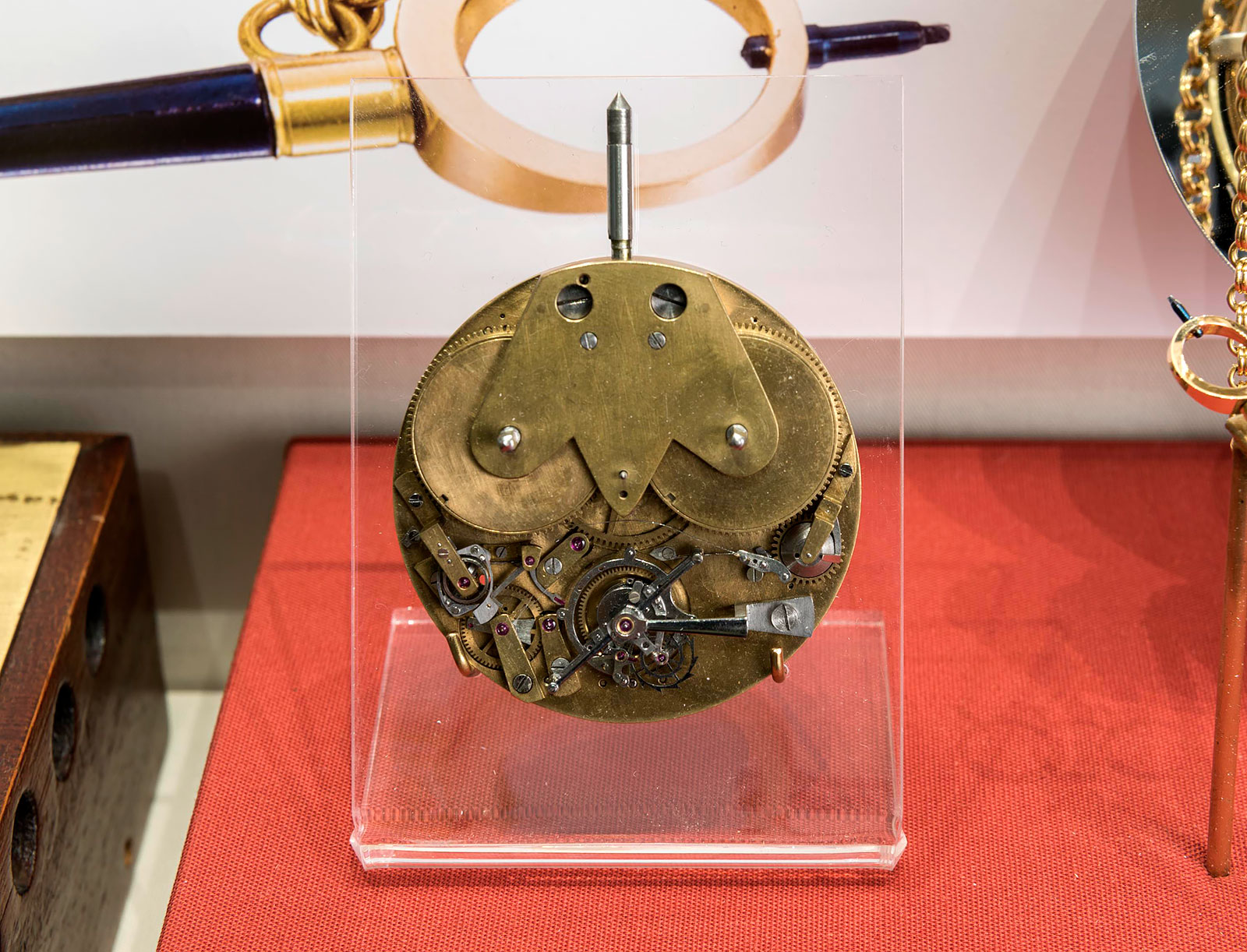

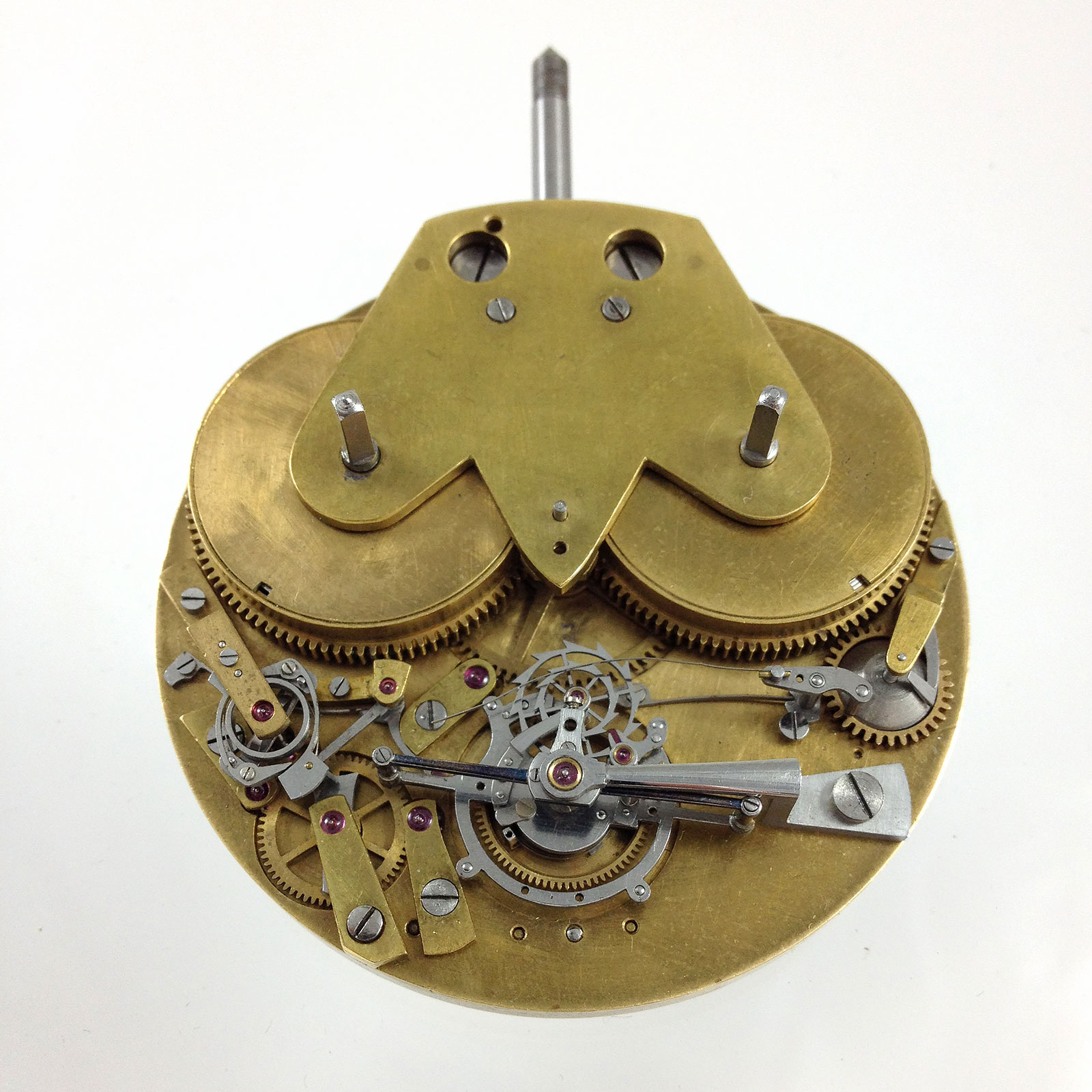

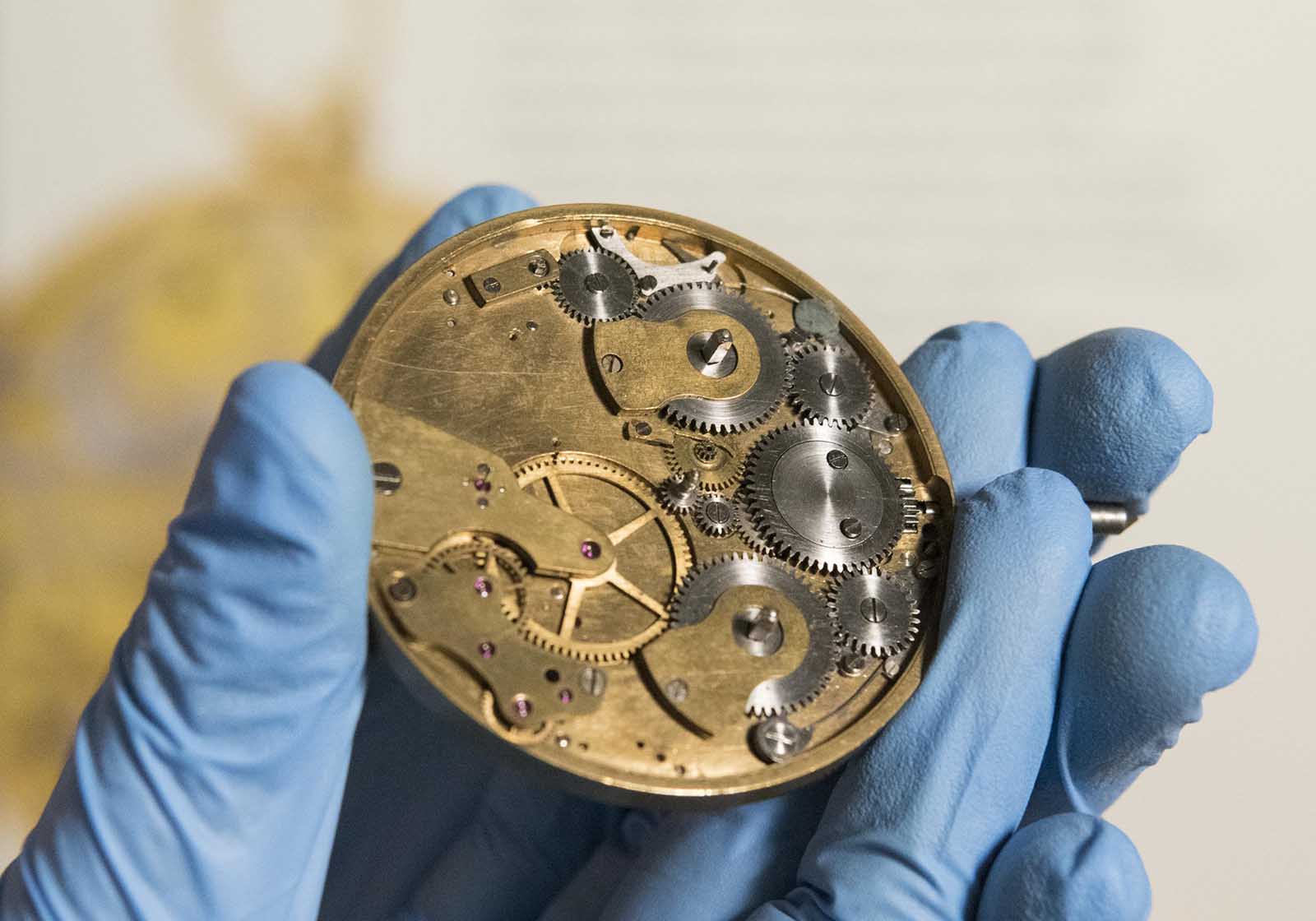

The unfinished Daniels movement in the George Daniels exhibit in the Clockmakers’ Museum. Photo – Science Museum

Like many great watchmakers over the ages, Daniels’ pursued perfect chronometry throughout his career; inventing a novel, superior escapement was perhaps his greatest achievement. And he managed to do it twice.

Having observed that the sliding friction in the conventional Swiss lever escapement affects the rate of a movement over time, he set about developing solutions. He invented two escapement types: one inspired by a 18th century Abraham-Louis Breguet idea, while the other was the entirely original and more famous co-axial escapement.

Despite the tremendous accomplishment of the co-axial, Daniels only incorporated the lubrication-free escapement in nine complete timepieces – seven pocket watches and two wristwatches – and one movement that was still a work in progress when Daniels passed away in 2011.

Ultimately unfinished

Daniels had been working on the movement for over a decade, having started on it in 1998 and then working on it off and on over the following years. But as Daniels’ health began to falter, “life overtook him” as Roger puts it, and work was stopped with the movement half-complete.

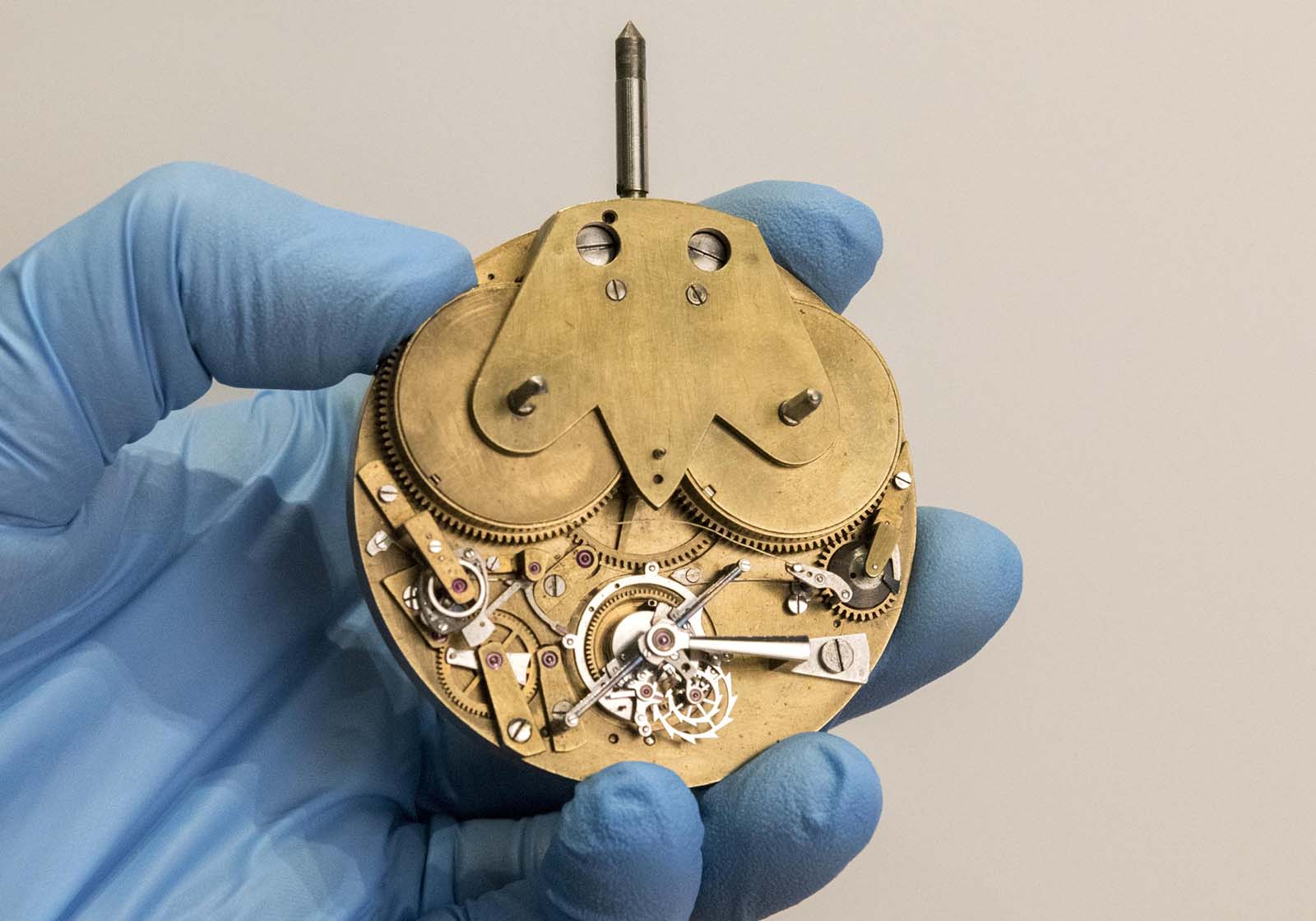

Roger has inherited the task of finishing the watch, which will be a lengthy process. Despite the major components of the movement being present – the notable omissions are the balance wheel and hairspring – there are still bits and pieces that need to be made, as well as substantial refining and adjustment – “lots of refining” according to Roger – of the components.

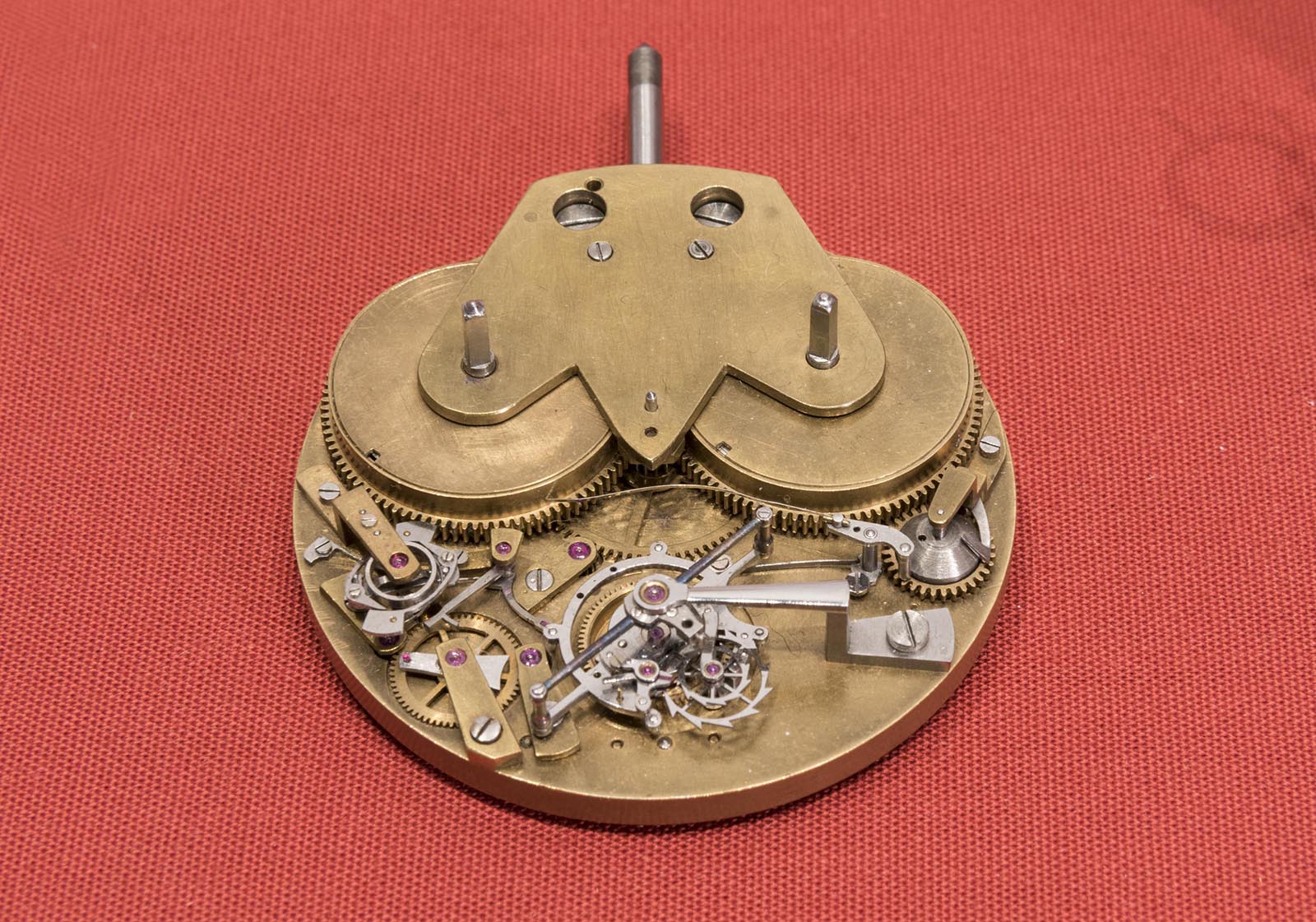

The movement as Daniels left it in 2011. Photo – Science Museum

In fact, filling in the blanks is perhaps as much of a challenge as building a brand new movement from scratch, because Smith has to extrapolate what was meant to be.

“The interesting thing about George and his watchmaking is that there are no detailed drawings for any of his watches. Everything was created in his mind’s eye and then developed as he built the watch,” explains Smith.

“Although George did make a watch with a similar specification in 1975, there are no drawings for this [unfinished movement] and this will be the challenge. First of all, to work out what he wanted to achieve with the piece, and then to try to complete it for him.”

Easily reminiscent of others Daniels watches, the unfinished movement features twin barrels with Daniels’ signature keyless winding and power reserve indicator, as well as one-minute tourbillon with co-axial escapement and 15-second remontoir d’egalite.

The unfinished Daniels, front. Photo – Roger W. Smith

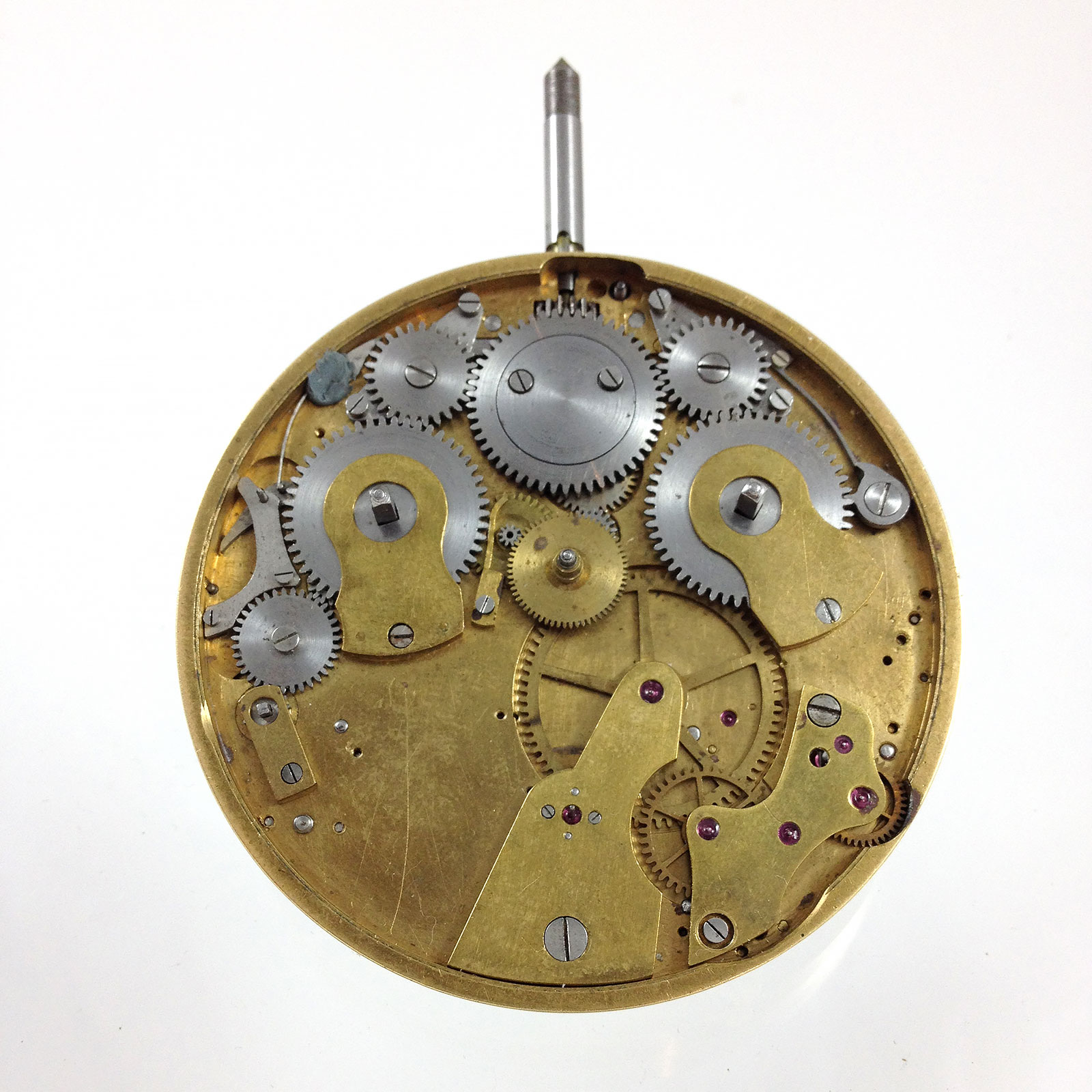

The unfinished Daniels, back. Photo – Roger W. Smith

Double-wheel and co-axial

The particular combination of complications in the unfinished movement is arguably the ultimate evolution of Daniels’ pursuit of precision timekeeping over his five-decade career.

At the same time Daniels was developing the co-axial escapement in the mid 1970s, he also built a pocket watch equipped with an independent double-wheel escapement that was inspired by Breguet’s echappement naturel, or natural escapement.

Commissioned by American industrialist and watch collector Seth Atwood, who wanted a timepiece with an entirely novel escapement, the pocket watch was completed in 1976, but it was inspired by an idea almost two centuries ago. English watch collector Cecil Clutton, a longtime Daniels patron, was so impressed by Atwood’s watch that he ordered an identical example that is now in the British Museum.

Invented in 1789, the natural escapement was Breguet’s attempt at a lubrication-free escapement. Though sound in basic principles, the technology of the day meant that the natural escapement never made it to serial production.

Atwood’s commission for a watch with “an escapement like no other seen before”, as described recently by Roger Smith, led to Daniels taking a slightly different approach from Breguet’s original idea.

The Daniels pocket chronometer with independent double-wheel escapement, made for Cecil Clutton in 1976. Photo – The British Museum

The movement of the Clutton watch. Photo – The British Museum

Daniels’ version had two escape wheels that were each driven by independent gear trains, which eliminated most of the hurdles faced by Breguet – primarily play between the escape wheels – in one masterful stroke.

Though his double-wheel escapement was installed in several watches, including Daniels’ most famous (and now most expensive) watches – the pair of Space Travellers – it was a dead end.

The George Daniels Space Traveller pocket watch, featuring a double-wheel escapement and twin, independent going trains, each powered by its own mainspring

Having been invented to satisfy an important client’s desire for something novel, the double-wheel escapement also had intrinsic limitations.

One was its construction: the two escape wheels, each driven by an independent gear train, could not be combined with a tourbillon. Several years later, fellow English watchmaker Derek Pratt eventually accomplished a tourbillon with a double-wheel escapement – but powered by a single gear train.

Due to the space needed for an additional train of wheels and the limitations in the geometry of the escapement, Daniels considered the double-wheel escapement to be impractical for a wristwatch. Decades later, English watch brand Charles Frodsham became the first and only maker to implement the escapement in a wristwatch with its Double Impulse Chronometer, but it is a large timepiece built for collectors.

Daniels’ ambition

Daniels’ practical approach to innovation – he wanted to change watchmaking on an industrial scale – meant his primary focus was always on the co-axial escapement. It was an invention that could potentially be produced on a large scale and installed in almost any movement.

This was a more compact solution that dispensed with the complication of a second gear train, and could be incorporated into a tourbillon if need be. Most importantly, the co-axial could be industrialised – and it eventually was, by Omega. Today the co-axial escapement is the flagship feature of the Swiss watchmaker’s high-performance movements.

A trio of George Daniels timepieces in the Clockmakers’ Museum, including the Space Traveller II (centre). Photo – Science Museum

Being the very last pocket watch Daniels made, the unfinished movement is naturally fitted with the co-axial escapement. In some ways, it is the final flourish of a dream that Daniels only realised posthumously, once Omega started manufacturing the co-axial on a mass scale several years after his death.

In fact, the movement is both interesting and significant because it represents the first Daniels movement that combined a tourbillon with the co-axial escapement and a constant force mechanism in the form of a remontoir.

The inclusion of a remontoir is particularly notable as the device is rarely found in Daniels’ work, except for the 1975 pocket watch cited by Roger above, which also includes a similar 15-second remontoir, paired with a one-minute tourbillon and a spring-detent escapement.

Constant force

In his book Watchmaking, Daniels described the remontoir as “by far the best method of smoothing the power supply, but it is complex and costly to make.”

He continues, “For this reason, watches with remontoirs are very rare and this, combined with their attractive action, gives them a special place in the affections of the connoisseur of mechanics. The fact that the mechanism is quite unnecessary merely adds to its charm.”

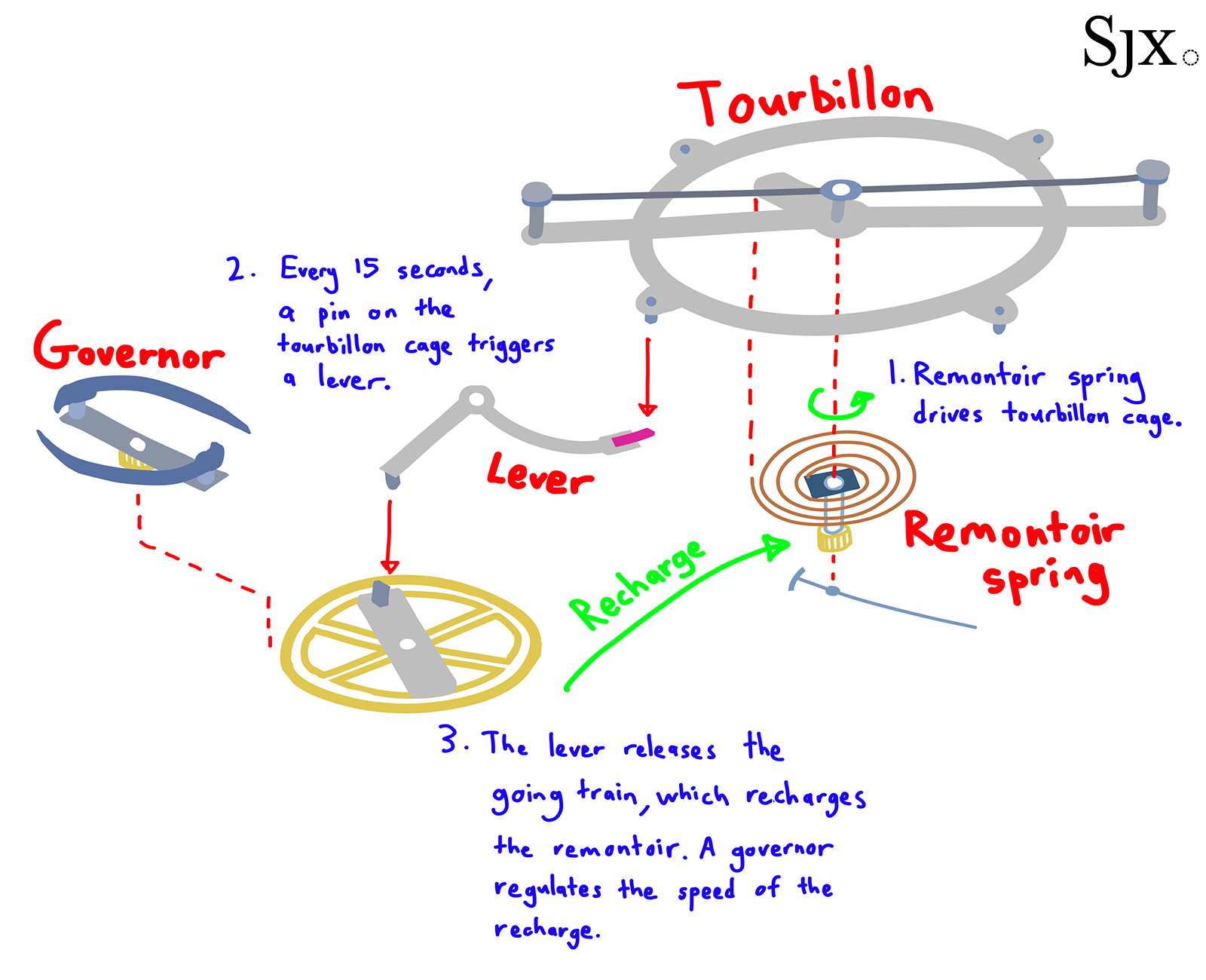

A constant force mechanism centred on a small, coiled spring that discharges and then rewinds after a fixed interval, the remontoir isolates the escapement from the vagaries of the going train. Consequently it eliminates a host of variables that could cause fluctuations in rate, including excess or inadequate torque from the mainspring (when it is fully wound or nearly empty respectively), and friction in the gear train.

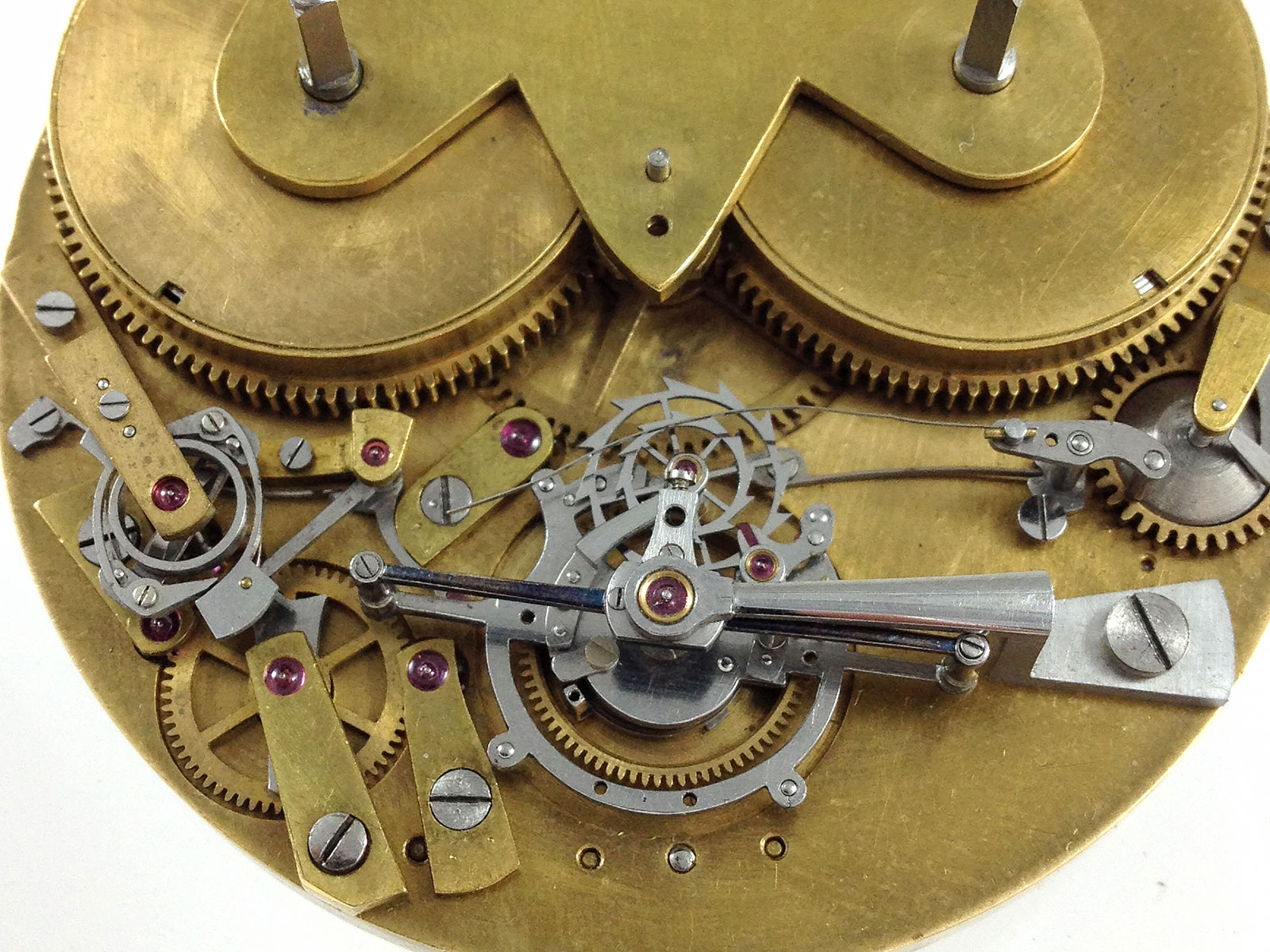

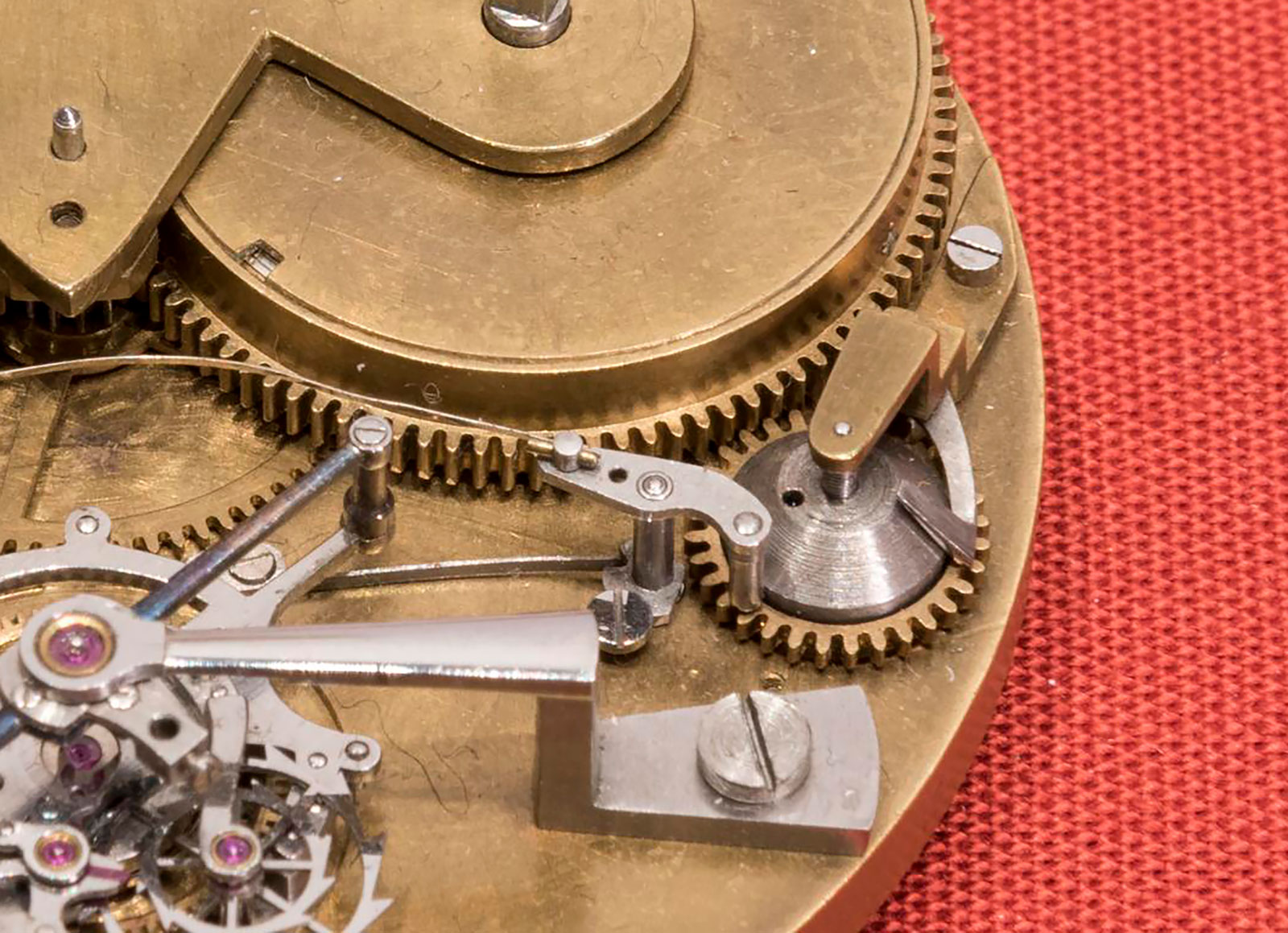

The tourbillon and remontoir, minus the balance wheel and hairspring. Photo – Roger W. Smith

Located on the fourth wheel and hidden underneath the tourbillon cage, the remontoir spring is the only source of power to the escapement, providing a small, constant dose of energy as it unwinds.

The lower cage of the tourbillon is fitted with four teeth, each carrying a pin that catches a pallet jewel at the end of a lever. The lever in turn releases the remontoir train, which rewinds the remontoir spring.

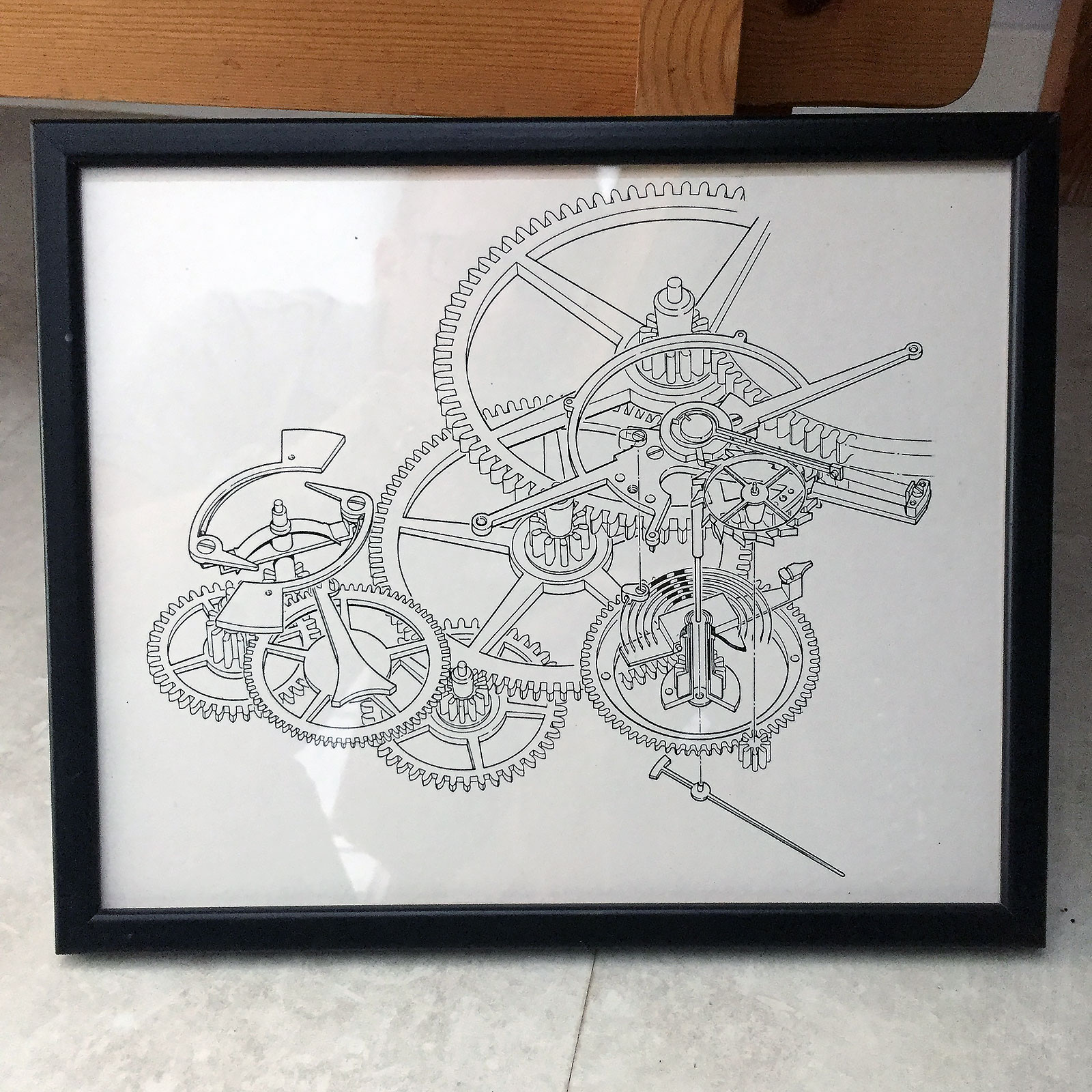

A simplified take on the remontoir mechanism

Because the tourbillon is a conventional one-minute tourbillon with its cage making one revolution every 60 seconds, and the four teeth are equidistant on the lower cage, the release and recharge happens every 15 seconds – an interval favoured by Daniels.

Roger himself has also employed a 15-second remontoir in his own pocket watch in the past. He points out that “a 15-second remontoir is preferable to a one-second because rewinding happens less often and therefore generates less disturbance on the mechanism.”

And on the left of the tourbillon is a governor (similar to that found in chiming mechanisms) that regulates the rewinding mechanism, moderating the rate of the gears when they rewind the remontoir spring. It also allows enough time for the tourbillon cage pin to pass the lever, thus blocking the remontoir train after one revolution and resetting it to its initial state.

The large, gilded third wheel that drives the tourbillon, visible on the left of the central axis. Photo – Science Museum

A detailed drawing of the remontoir mechanism and part of the going train. Photo – Roger W. Smith

The rest of the watch

Dominated by two large barrels, the unfinished movement is stylistically similar to other Daniels calibres, which are in turn often modelled on 19th century Breguet creations.

The movement features twin barrels that drive the second wheel directly and simultaneously; in other words, the mainsprings unwind in parallel.

The other key feature of the movement is the cone-and-screw power reserve mechanism, a recurrent element in many Daniels pocket watches. When it came to the power reserve display, Daniels always preferred the aesthetics of the cone and screw over the differential gear system, according to Roger, as the latter was visually underwhelming.

The cone and “feeler” arm of the power reserve mechanism are visible at three o’clock. Photo – Science Museum

An easily recognisable mechanism due to its distinctive components, the cone-and-screw mechanism relies on a truncated cone that moves up and down along an arbour according to the state of wind of the mainspring. The arbour is in turn linked to the barrel via gear at the base of the cone.

The cone is accompanied by a “feeler” lever that measures the vertical motion of the cone and transmits the information, via a fan-shaped rack and pinion, to the power reserve hand on the dial.

Lastly, as with all of his pocket watches since the mid 1980s, the unfinished movement incorporates another one of Daniels’ inventions – keyless winding. That means the completed watch will have neither a crown nor a stem, but just a bow that works like a crown for setting and winding the watch.

The George Daniels display at the Clockmakers’ Museum. Note that the two pocket watches have keyless winding, with just a bow instead of a crown. Photo – Science Museum

Finishing the unfinished movement

Property of the George Daniels charitable trust, the unfinished movement is now on display at the Clockmakers’ Museum, but will eventually be completed by Roger. Speaking to us in an interview last year, trust chairman David Newman indicated work on the watch might begin this year. What will happen to the watch once it is finished is also unknown, although an obvious possibility is selling the completed watch with the proceeds going to the Daniels trust.

According to Roger, finishing the movement and turning it into a watch would take anywhere from six months to a year – and then Daniels’ final masterpiece will be complete.

Corrections February 24, 2019: Contrary to an earlier version of the article, Daniels did not abandon the idea of the double-wheel escapement, as it was created at a client’s request as a technical novelty, and not meant to be a long-term, industry-changing innovation like the co-axial. The text has been corrected to reflect that as well as include more information on the progress from double-wheel to co-axial escapement, with input from Roger W. Smith.

Back to top.