In-Depth: Blancpain Grande Double Sonnerie

Blancpain strikes a new chord — sealed with a Kiss.

Blancpain has just unveiled its most complex modern-day watch, the Grande Double Sonnerie, to mark its 190th anniversary. This CHF1.7 million grand complication signals Blancpain’s return to the highest tier of haute horlogerie.

One of the most technically ambitious chiming wristwatches ever made, the Grande Double Sonnerie incorporates traditional complications: grande and petite sonnerie, minute repeater, flying tourbillon, and retrograde perpetual calendar, but also offers an unexpected twist with two distinct chiming melodies, a Westminster chime plus a a bespoke sequence composed for Blancpain by Eric Singer of rock band Kiss.

Initial thoughts

It has been some time since Blancpain unveiled a truly headline-grabbing complication. The manufacture made its name in this arena with the 1735 of 1991, but in the decades since, its output has leaned toward more conventional high-end offerings — perpetual calendars, tourbillons, carrousels, and chiming watches — while its commercial momentum has come largely from the Fifty Fathoms and Villeret triple calendar.

The unexpected Grande Double Sonnerie is therefore a reminder of what Blancpain can do at the very top level of watchmaking. The Le Brassus-based manufacture tends to be overlooked when speaking of high horology today, but the Grande Double Sonnerie should remind enthusiasts how sure-footed Blancpain is in this regard.

Even before considering the many complexities of the timepiece, the watch impresses from the first sight: a sea of polished levers, gears and hammers fitted with eccentric sub-dials and a wide tourbillon aperture.

It takes a moment to get acquainted with the Grande Double Sonnerie’s dial; there is a set of central time telling hands, a thin date sector paired with a pointer hand, a day of the week indicator and a co-axial leap year cycle and month indicator — hinting at a perpetual calendar complication. Despite this complexity and metallic palette, the dial is surprisingly legible once you get used to it.

But the true centrepiece is the chiming mechanism. Although the name “Double Sonnerie” might suggest the familiar pairing of grande and petite sonnerie, here it refers to the ability to sound the time in two different melodies: the traditional Westminster chime or a bespoke sequence written exclusively for Blancpain.

The composer behind that second melody will surprise many: Eric Singer, best known as the long-time drummer and occasional vocalist for Kiss. Blancpain approached him to create a signature tune for the watch — an unlikely meeting of classic haute horlogerie and hard-rock pedigree, made more unexpected by the fact that Singer was tasked with composing a soft, lyrical melody.

This collaboration might be one of the most unexpected of recent times. Blancpain, an utterly classic manufacture, working with a famous hard rock drummer would seem unlikely — especially since said drummer was tasked with coming up with a soft sonnerie chime.

The result is a chiming watch unlike any before it. Owners can switch freely between the two melodies, in addition to selecting the various striking modes, and they can also activate a minute repeater. These are familiar elements of high-end striking watches, but the ability to alternate between two distinct chiming patterns is genuinely novel.

At 47 mm the watch is large, yet it’s surprisingly slim and comfortable enough on the wrist — an encouraging sign for a complication of this scale. The case is deliberately understated, allowing the mechanics to take centre stage, while the finishing throughout is at Blancpain’s highest level, on par with many independents.

In fact, the finishing of the movement is entirely traditional – almost everything is done by hand, including anglage with entirely manual tools, in a small workshop dedicated to high-end complications. This old-school approach to finishing is uncommon at large brands, and underlines Blancpain’s haute horlogerie capability.

The two precious metal versions side by side.

Two versions are offered, in 18k white or rose gold, with output capped at two pieces per year. Between the two versions, the one in rose gold looks more luxurious, although I personally prefer the more restrained white gold version. The colder, crisper look of white gold and grey hues seems to suit the complicated piece better.

The price of CHF1.7 million (taxes included), reflects the rarity and ambition of the project.

A most modern sonnerie

Watchmakers and collectors alike hold the grande sonnerie in especially high esteem. True clockwatches like this remain rare.

Blancpain brings something new to the small circle of brands that have managed to produce this complication: the ability to choose the specific tune on command, using a simple pusher on the case that, when actuated, switches between the classic Westminster carillon to Blancpain’s own Singer-composed tune.

The Westminster chime (also known in clockmaking as “Cambridge quarters”) refers to a specific chiming sequence, which makes use of four different hammers and four different gongs to sound the time each quarter of an hour. The name comes from the Westminster clock tower, better known as Big Ben.

A grande sonnerie chimes every full hour and then the hour and quarter, every quarter. A petite sonnerie chimes the full hour on the new hour, and then only chimes the quarters on the quarters without repeating the hours. Notably, while most clock watches only chime the hours on the new hour, the Grande Double Sonnerie chimes out all four quarters, like a real grandfather clock.

Having four hammers and four gongs provides the complication with a richer and more nuanced sound, compared to simpler chiming watches with only two or three hammer and gong pairs. With this arrangement, the movement can play four distinct notes. In the Grande Double Sonnerie’s Calibre 15GSQ those notes are E, G, F, and B. This palette naturally raises the question: could another melodic sequence be created from these four pitches? As it turns out — yes.

Eric Singer is a drummer and watch collector, famously part of the Kiss. He’s also collaborated with Black Sabbath, Gary Moore and Brian May throughout his career. Also a friend of Blancpain chief executive Marc Hayek, Mr Singer was a fitting choice for “orchestrating” Blancpain’s alternative chime. The artist accepted the challenge of composing a special melody — which turned out to be a real challenge, since four notes may be a lot for a movement, but apparently quite constraining for a musician.

Blancpain says the watch took more than eight years to develop, resulting in 21 patent applications and 13 patented solutions incorporated into the final construction. The key innovation is the mechanism that allows the user to switch between two musical sequences — a system that required entirely new components and multiple safety devices to prevent damage during operation.

The symmetric rounded pushers are for changing the chime melody and for actuating the minute repeater. A conventional slider for selecting the sonnerie mode: Petite, Grande and silent.

Without diving too deeply into the mechanics of chiming watches, it’s helpful to outline the basic principle behind the melody switching. In simple terms, a watch chimes because a toothed rack, driven by the movement, engages the hammers in sequence. Each tooth lifts a hammer and then releases it onto its gong, producing a note. The melody is determined entirely by the arrangement of teeth on the rack.

This basic explanation shows that the tune depends solely on the rack’s tooth pattern — much like the pinned cylinder of a music box. Change the pattern, and you change the melody. That, in essence, is what Blancpain has achieved, albeit in a highly sophisticated form.

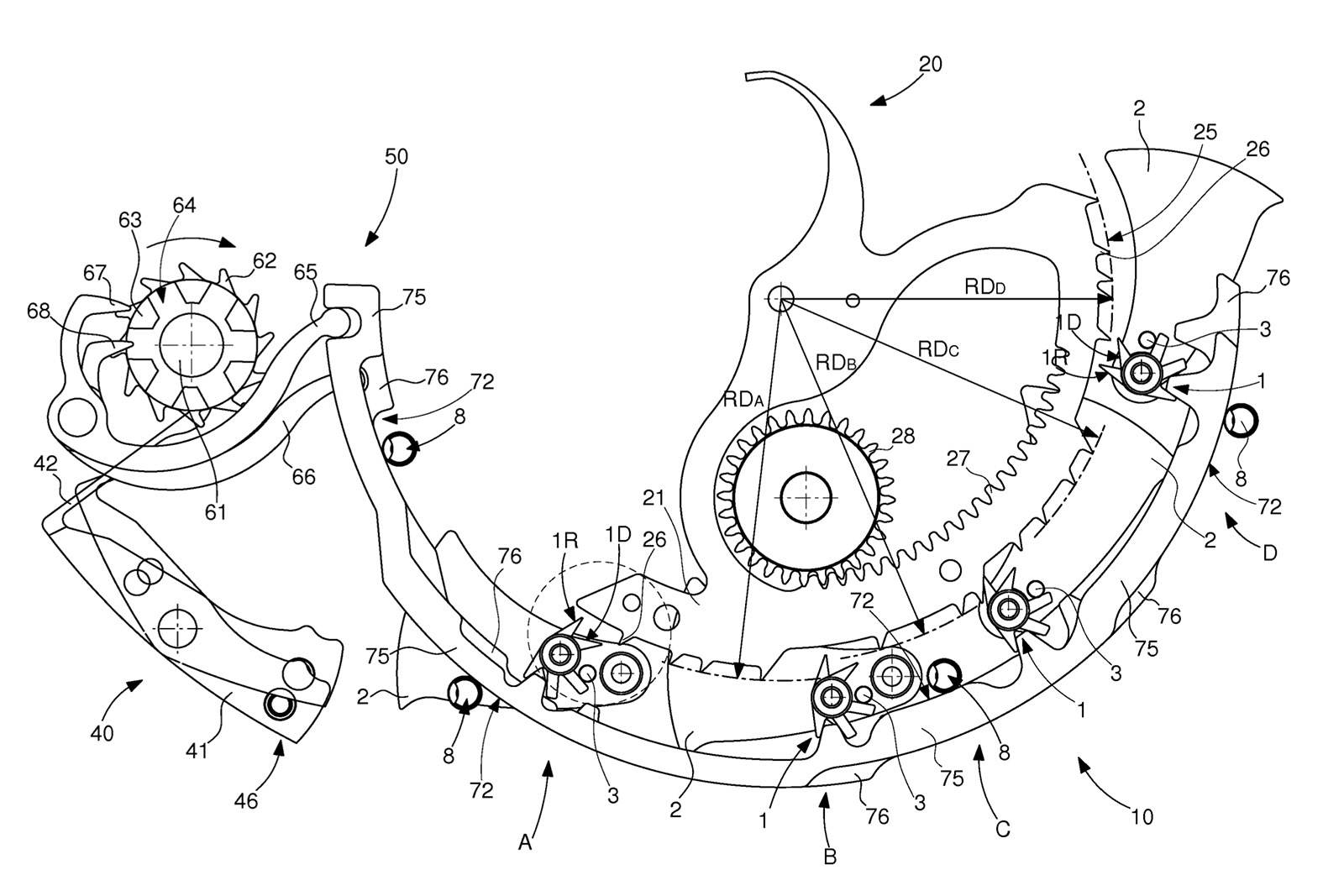

The figure below is extracted from patent EP3136188 and shows a glimpse of the simplified selector mechanism. As we’ve established, two differently-toothed racks make for two different chiming patterns. Blancpain went to implement a double-levered rack, with each level encoded with a specific melody: one with the Westminster chime and the second with Mr Singer’s bespoke composition.

Each of the four hammers has a set of hooks, which can take up different positions. The hooks are arranged on two levels and are independent. The hooks on each level can be either active or inactive — meaning they are either raised and can be engaged by the toothed rack or they sit flush with the hammers.

Two long lever arms engage with the hook pieces. The lower lever controls the lower hooks and the upper lever the upper hook members respectively. The gist of this interaction is that cam-like profiles in the levers synchronously force the hooks in either their active or inactive positions.

The column wheel and two-level racks are visible on the caseback side.

The levers are moved by a column wheel—similar to the control system of a chronograph—which ensures that the two positions (active and inactive) are complementary. In other words, only one set of hooks can be active at any given time; the two sets are never active simultaneously.

As the chiming starts, the double-level rack glides over and engages whichever set of hooks is active. Thus, it is either the Westminster chime that is played or Mr Singer’s. During the chiming sequence, one level of the rack engages the hammers in its preprogrammed sequence, while the other simply glides over the inactive hooks. Clever geometry was also employed to make sure that each toothed sector on the rack engages only the right hammer, so the rack profile has decreasing radii.

An underside view of the double level rack.

Some more patents cover the safety system which assures the user can’t switch up melodies mid-chime, which would probably either break or bind the hook assemblies. Other more “common” safety implements assure the sonnerie works are isolated during chiming, such as blocking time setting or the actuation of the minute repeater. In total, there are five distinct safety mechanisms protecting the Grande Double Sonnerie.

The four circular gongs were designed specifically for this calibre, with a novel construction and geometry (also the subject of a patent) which makes them easier to tune to the desired frequency. In this particular embodiment, two gongs are concentric and stem from the same fixture, with two other arranged underneath, in a more classical fashion. Blancpain engineers tried out multiple alloys for the best acoustic response and seem to have ultimately settled on a rose gold alloy.

Custom construction of one-piece pair of gongs.

Another patented feature is the 5N gold acoustic membrane that connects the main case body with the sapphire glass fixture. Manufactured through electro-forming, the membrane works as a mechanical amplifier of sound.

Interestingly, the sapphire front glass is not set directly into the bezel or case body, but is rather supported directly by the gold membrane through a dedicated fixture. Thus the sapphire glass and its fixture are allowed to vibrate slightly inside the bezel.

The four hammers are fully visible on the dial side along with a glimpse of the gold gong assembly.

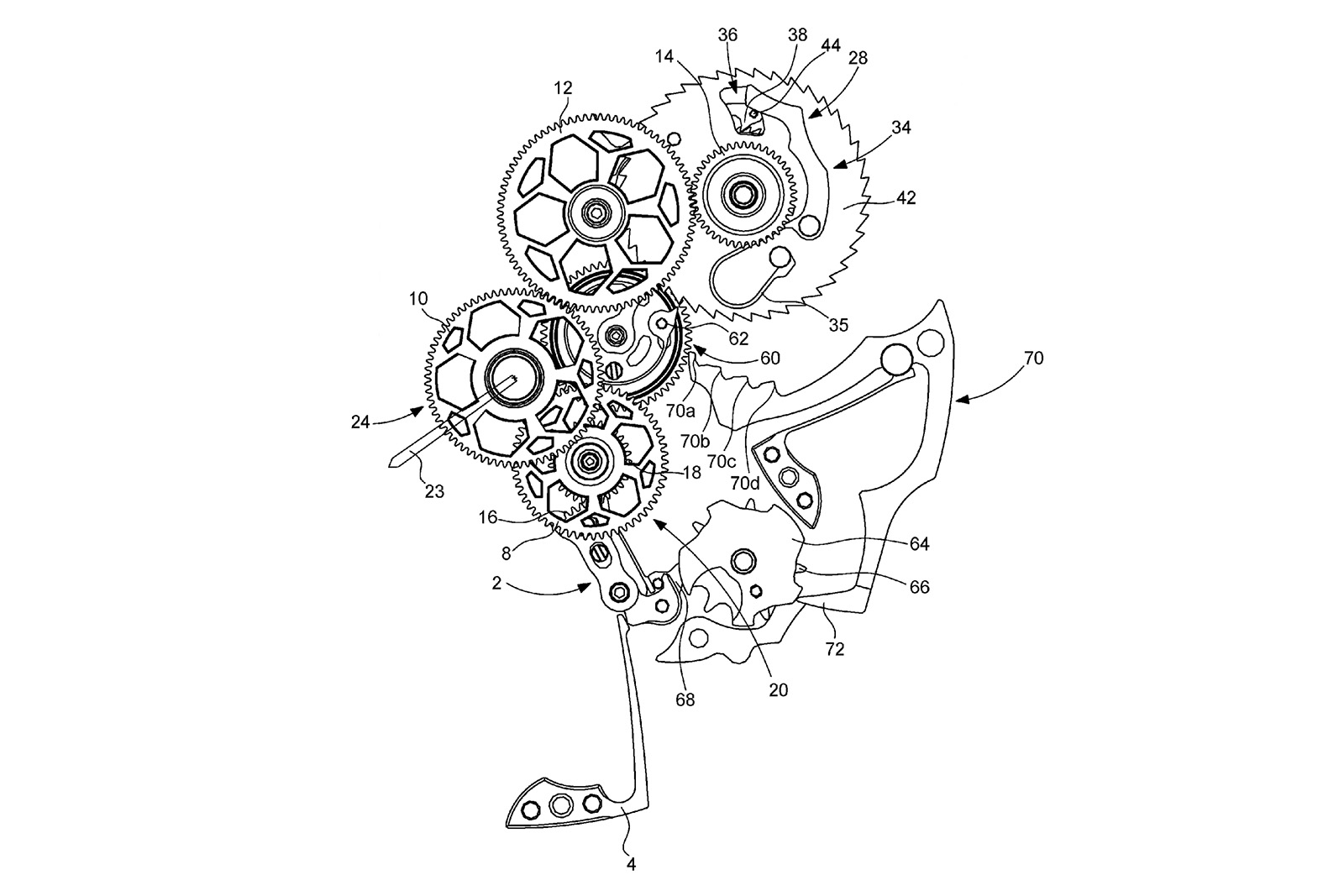

A very modern implement inside this movement is the magnetic governor, which regulates the chiming speed. In any sort of chiming watch, spring power is directly discharged into the strikeworks and there is a need for a device to regulate the striking speed.

Early centripetal governors were even used in gramophones, to regulate the speed at which vinyls were played. They work by acting as a sort of mechanical capacitor, braking the fast-rotating gears by harnessing angular kinetic energy.

The magnetic device used here is a silent governor, braking the discharge speed of the barrel by having a rotor slowed down by moving in a magnetic field. As it revolves, the governor rotor generates an electric potential, which encounters resistance from the magnetic field. The assembly looks a little like a stator, which is a sort of electric generator. Such a system was first used by Breguet in La Musicale, reflecting the innovation shared inside the Swatch Group.

Since the sonnerie function draws its power from its own separate barrel, the minute repeater can also be run from the same source, so there is no need for a sprung slider to arm the complication. As such, it can be activated on demand by a simple pusher on the case. The dedicated barrel stores sufficient energy for a full 12 hours in grande sonnerie mode.

Retrograde perpetuity

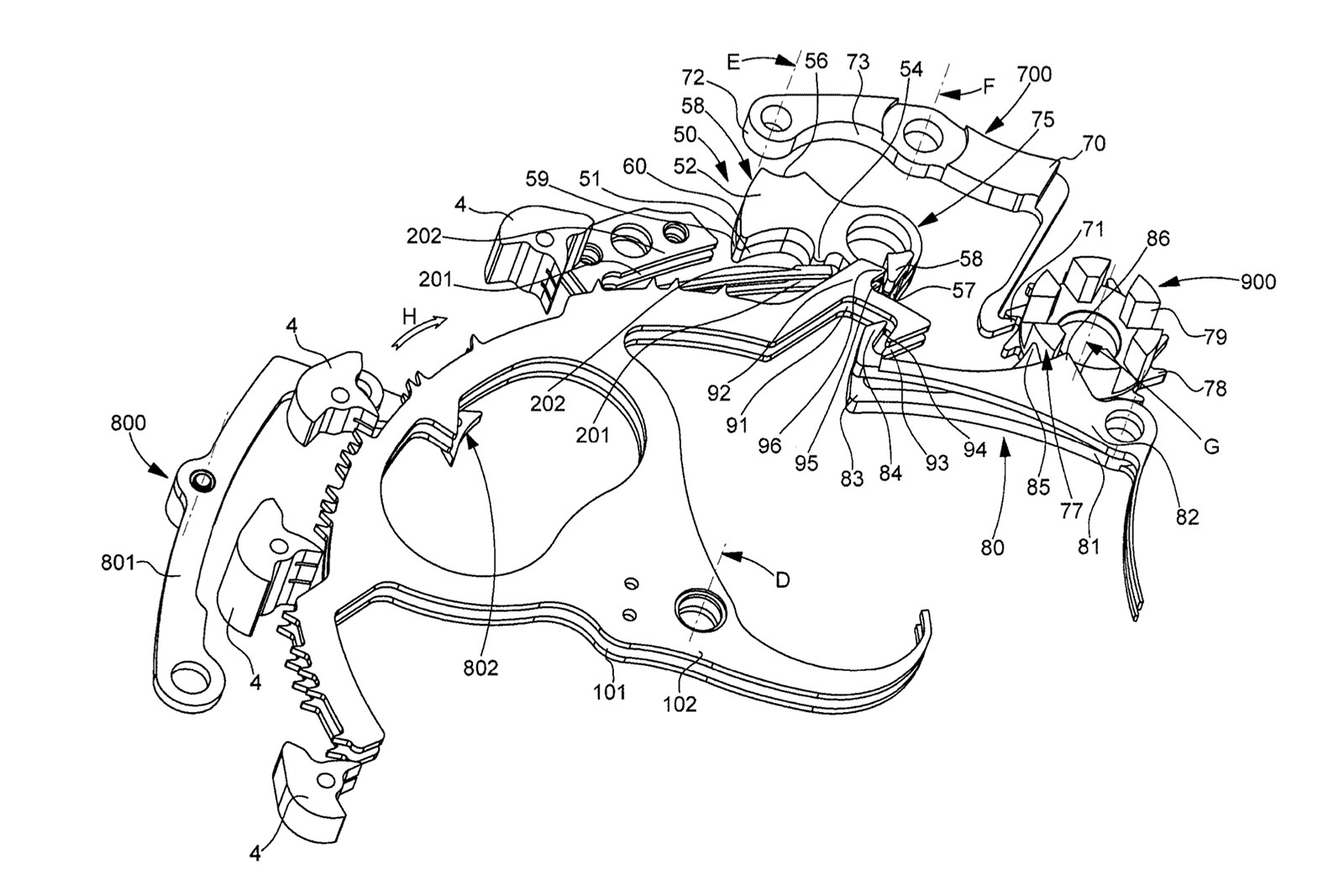

Integrated within this impressive sonnerie calibre — and visible on the dial side — is a compact retrograde perpetual calendar. Although the Grande Double Sonnerie is built around its chiming mechanism, the perpetual calendar is an achievement in its own right.

At first glance it appears to be a fairly conventional perpetual calendar, albeit with an unconventional layout. A large sector on the left displays the retrograde date, while two smaller sub-dials show the day of the week and a co-axial leap-year and month indicator. Where Blancpain could have employed a traditional perpetual calendar paired with a snail cam and rack system, its watchmakers instead chose to rethink the mechanism altogether.

The compact perpetual calendar mechanism is barely discernible on the dial side.

The subject of a couple of patents, Blancpain’s new retrograde perpetual calendar is built to improve some issues associated with both traditional perpetual calendars and generic retrograde indicators. Blancpain engineers argue that in snail cam and rack indicators, the hand is under no direct tension and especially for small increments (like those on a 31-incremented date sector) it may not index properly and over- (or under) shoot its mark.

Blancpain began by reworking the retrograde mechanism itself, replacing the traditional setup with a ratchet wheel, gear train, and linear spring. The retrograde hand is mounted on one of the intermediate gears, so it is never idle and always kept under tension. A conventional date finger engages the large ratchet wheel, advancing it by one step each day.

Just like with the sonnerie function, Blancpain went for a very complex and refined construction for the perpetual calendar, but the gist is simple enough to make out. The system takes advantage of the retrograde’s indication tendency to always snap back to the “1” indication.

A feeler lever engages with a fairly ordinary month cam, reading the months’ lengths. In the case of 31-day months, it triggers part of the ratchet mobile, causing the spring to intension and snap the retrograde back to “1”. In the case of 30, 28 and the occasional 29-day months, the feeler lever simply engages the ratchet trigger earlier and snaps the retrograde hand.

The action is simple in theory, but took a lot of springs, fingers and gear calculations to get right. The concept is not dissimilar to the MB&F LM Perpetual, but this present version bears more resemblance to the George Daniels’ original design used in the Grand Complication. The concept is basically the same, although Blancpain’s construction is definitely the more refined between the two. Setting of the perpetual calendar is done in classic Blancpain style, with concealed collectors under the lugs, which are integrated directly within the movement.

Shapes and finishes

Blancpain has done an impressive job making Calibre 15GSQ not only a technical achievement but also visually appealing. Chiming complications are inherently classical, and such movements are typically paired with closed dials that conceal most of the striking works.

When watchmakers choose to reveal the sonnerie racks and levers beneath a translucent dial, legibility often suffers and the watch can appear overly technical. Striking the right balance between visual openness and elegance is therefore difficult.

The cal. 15GSQ was clearly constructed with complete openness in mind, never meant to be hidden away under a closed dial; both sides of the complex movement are equally visible and thoughtfully arranged. The dial side is especially appealing, since all the supporting bridges are generously cut-out, revealing the various gears and springs underneath.

The dial is just a ring of 5N gold, with raised numerals and a broad sector showing the month dates. The sector is plenty legible, occupying almost half of the precious ring dial. Smaller dials for the perpetual calendar are coarsely brushed, offering some nice contrast with the rest of the polished components.

The four hammers are on full display, mirror-polished with rounded anglage. The magnetic governor is visible as well, framed by a rounded Blancpain name plate. When any of the chiming functions are running, the user can admire the hammers striking and the dynamic dance of the governor on full display.

The bridges and mainplate are not merely plated, but are instead made out of solid 18K white or pink gold, with most visible surfaces mirror polished. The steel parts are finely brushed, as are the gears. All gears have the sporty and intricate spoke design unique to Blancpain, a subtle nod to the manufacture’s past collaborations with Lamborghini.

All visible edges are sharply beveled and the movement contains no less than 135 interior angles. Using gold instead of other metals gives a certain warmth and gravitas to the movement. The bevelling, along with the rest of the decoration, is done by hand the traditional way in a workshop focused solely on finishing high-end complications. For anglage, that means a file to carefully shape the bevels.

One of my favourite parts of the dial side is the the large aperture showing the flying tourbillon. The delicate complication is the latest embodiment of the original inverted flying tourbillon designed by Vincent Calabrese for Blancpain in the late 1980s. Upon its debut, its eccentric design prompted many to erroneously classify it as a carrousel, but it is in fact a tourbillon, albeit one with an off-centred balance wheel.

The modern design has a broad, mirror polished cage and a large free-sprung balance. The regulator beats at a modern 4 Hz frequency and features a silicon hairspring. While the modern material might seem out of place in such a classic timepiece, the tourbillon sits very close to the magnetic governor, so the need for non-magnetic materials is a true necessity.

Blancpain isn’t the only brand that uses a silicon hairspring for its range-topping products; Patek Philippe does the same for the ref. 6301P. The Grande Double Sonnerie runs for about 96 hours on a full wind, which is frankly impressive, coming from a single barrel.

The back of the movement reveals the intricate, multi-layered rack system, including the mechanism that switches between chimes. The high level of finishing continues here, with Geneva stripes on the barrel bridge, black-polished steel components, and two large sonnerie-style click wheels — a nod to traditional chiming clockwatches.

The back also features two discreet power-reserve indicators: one for the chiming functions and another for the timekeeping train. The two barrels are independent — one drives the tourbillon and perpetual calendar, while the other powers all of the striking mechanisms.

Each Grande Double Sonnerie is assembled by one of two dedicated watchmakers, who leave their personal mark on the piece. A hand-engraved name plate bearing the watchmaker’s signature is affixed to the reverse side of the movement. It’s a poetic way of connecting the owner with the craftsman — a gesture common among independent makers but rare for a large manufacture.

Key facts and price

Blancpain Grande Double Sonnerie

Ref. 15GSQ 1513 55B

Ref. 15GSQ 3613 55B

Diameter: 47 mm

Height: 14.5 mm

Material: 18k white or pink gold

Crystal: Sapphire

Water resistance: 10 m

Movement: Cal. 15GSQ

Functions: Hours, minutes, flying tourbillon seconds, perpetual calendar, grande and petite sonnerie, minute repeater and chime selector

Winding: Manual winding

Frequency: 28,800 beats per hour (4 Hz)

Power reserve: 96 hours

Strap: Crocodile with matching folding clasp

Limited edition: No, but production will be limited to 2 pieces each year

Availability: At Blancpain boutiques

Price: CHF1.7 million, taxes included

For more information, visit Blancpain.com.

Back to top.