Complicated Collectors: Henry Graves Jr.

Made for Manhattan.

By the early 1930s, Henry Graves Jr lived a life shaped by precision, inheritance, and permanence. It was from this vantage — both social and literal — that he took up residence behind the limestone façade of 834 Fifth Avenue, Rosario Candela’s neo-Renaissance co-operative that replaced hulking mansions with what contemporary coverage called “a series of luxurious homes” in a building that was promised to be “a worthy and lasting landmark”.

The promise held: in 2007 the New York Observer called the address “the most pedigreed building on the snobbiest street in the country’s most real estate–obsessed city.” This reputation was sustained in part by its prodigious roster of illustrious owners, from Berwind and Rockefeller to Murdoch and Blavatnik, names that reflect the same social altitude that drew Graves there in the first place.

834 Fifth Avenue where Henry Graves Jr. lived when he received the Supercomplication in 1933. Image – The New York Public Library/collage.

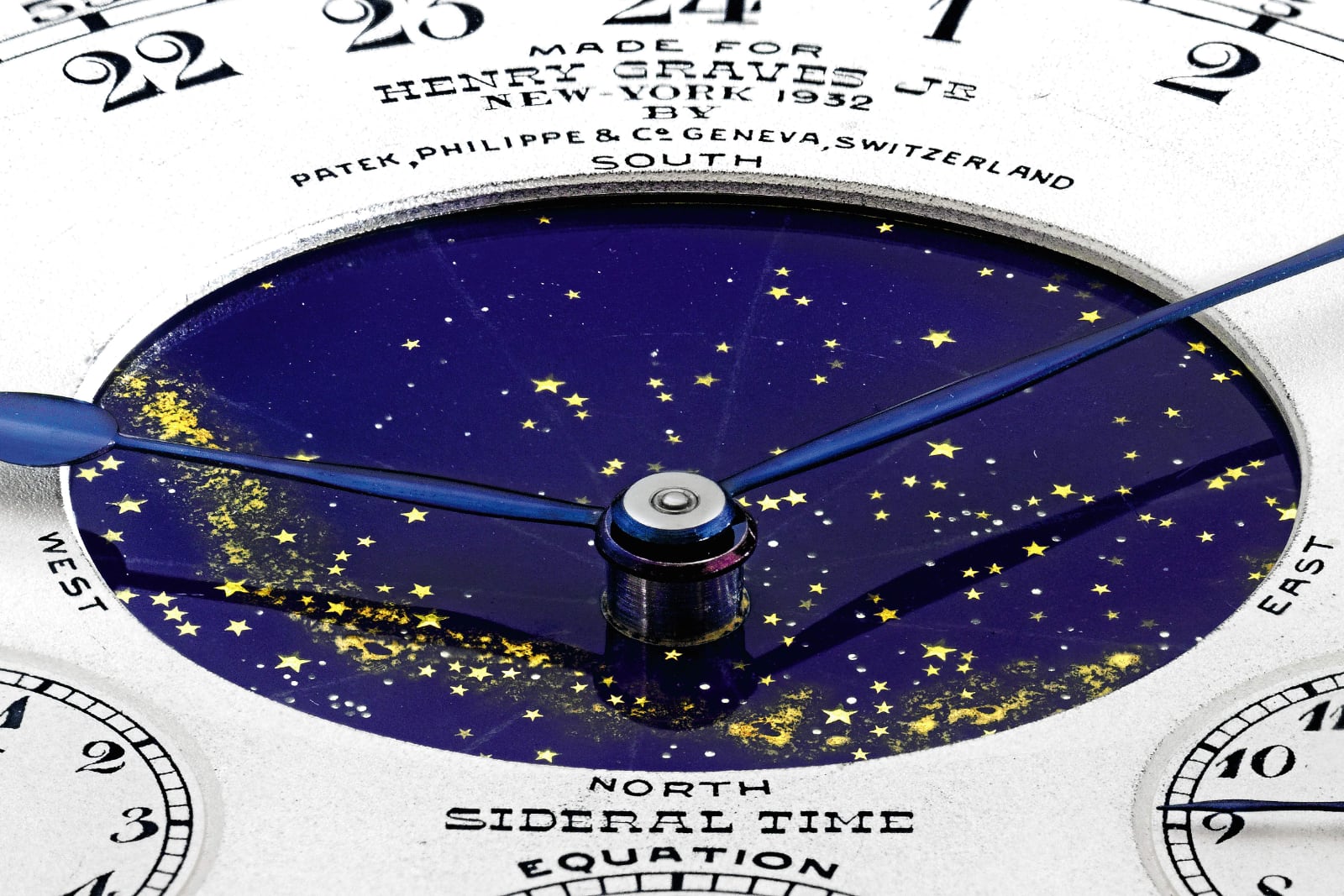

From the window of his high apartment, Graves could watch the constellations lift over the dark mass of branches and the curving drives, the lamps along the park paths thinning as the air cleared towards the river. Inside, in a room lined with paintings and prints, a heavy yellow gold watch lay on a table.

Opened on its reverse dial, it carried that same sky, compressed into enamel and gold, calculated for this exact latitude and this exact view. The Supercomplication framed the night above New York as a rotating chart, a map centred on 40°41′ north, with the Milky Way and the principal stars of the northern hemisphere plotted as if the back of the case were a small observatory dome turned flat.

Made for Manhattan

The astronomical display on the back of the Supercomplication was not decorative; it was carefully conceived for a single address. Inside the watch, a dedicated sidereal train runs at stellar speed, completing one rotation in a sidereal day, and the celestial disc on the back turns with it. The horizon line and the curved limits of visibility mirror what he could see when he looked out over Central Park.

At the edge of the disc, a 24-hour scale links sidereal and mean solar time, while the equation-of-time cam translates the difference between them into minutes that appear on the day-side dial. Sunrise and sunset for New York step forward across the year on a pair of sector scales, fixed to the same geographical assumption: the watch belongs under this sky. Wherever it travels, the rear dial remains loyal to Manhattan.

The Henry Graves Supercomplication No. 198’385 delivered in 1933. Image – Sotheby’s/collage

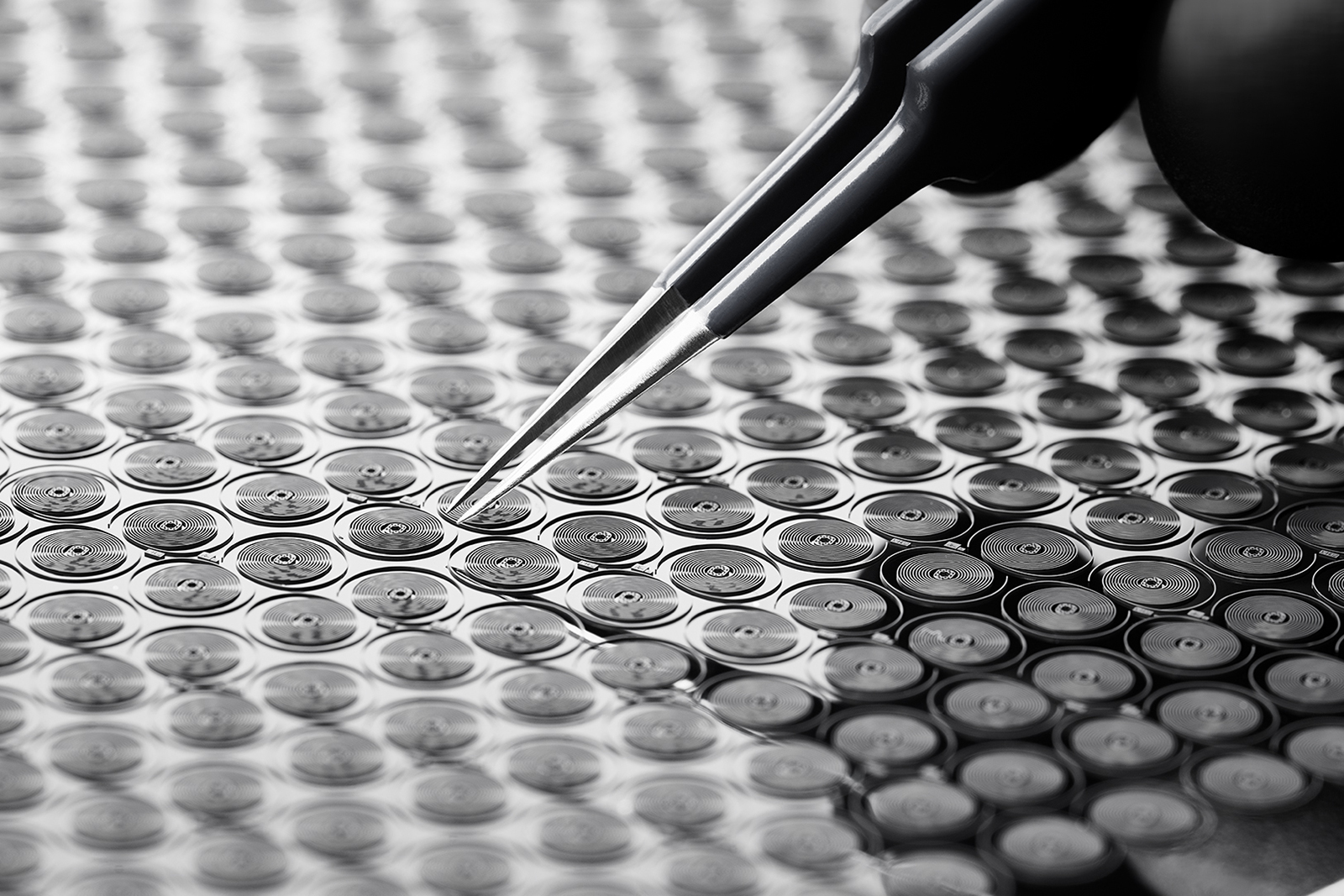

The path that brought this object to 834 Fifth Avenue runs through a different landscape. In the Vallée de Joux, far from Fifth Avenue, constructors and régleurs in and around Le Sentier spent nearly a decade moving from sketch to mechanism. The Piguet workshop, by then trading as Les fils de Victorin Piguet, took on the ébauche and the architectural responsibility. Victorin Emile Piguet’s sons and grandson divided tasks among a small constellation of specialists.

Paul-Auguste Golay built the calendar with its leap-year cam and discs for the day and month. Juste Olivier Aubert designed the winding and hand-setting works, making sure that a single crown and a ring of discreet push-pieces could govern every train. Luc Rochat and other case makers formed the thick bassine case that would house five gongs, two heavy dials and a forest of levers without ornamental embellishment.

The watchmakers’ correspondence shows that they thought in terms of lineage as much as in terms of any single client. When they argued about pricing, they reached instinctively for the benchmark complications that had defined the previous century such as Breguet’s “Marie Antoinette” and the Leroy no. 1. One letter weighs up the true cost of the so-called “Marie Antoinette”, another sets out the margin Breguet once achieved on a perpetual calendar and urges similar prudence for their own work.

A separate exchange drills into the leap year mechanism, checking that the year wheel’s 365¼-day rotation avoids cumulative error that would push the calendar several days adrift after a single cycle. The Graves commission, in their hands, becomes a reply to an entire tradition. The client’s name remained distant; their dialogue was with Breguet and Leroy as much as with Patek Philippe in Geneva.

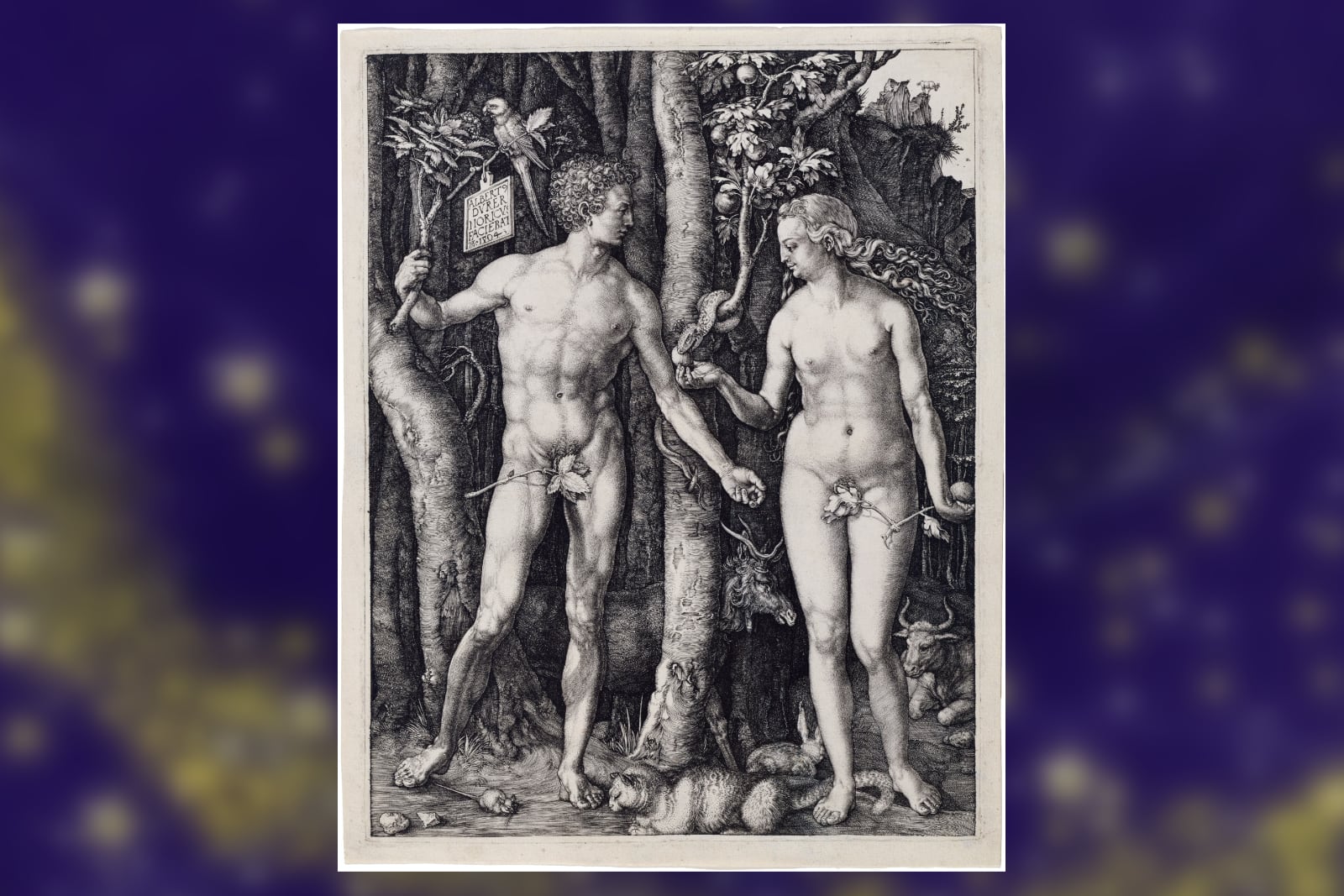

Dürer’s “Adam and Eve”, once in the collection of Henry Graves Jr. Image – Wikipedia/collage

In New York, the outlines of Graves’ life formed a different sort of constellation. Born in Orange, New Jersey in 1868, he inherited an “economic princedom” from his father, a founding partner of the Maxwell & Graves brokerage firm. The firm’s offices at 52 Broad Street generated substantial income from railroad and industrial securities, yet Henry Jr preferred to act as a trustee rather than as an entrepreneur.

He managed the assets and maintained his father’s seat, but devoted much of his energy to collecting paintings, engravings, coins, and paperweights. An auction of his prints, Masterpieces of Engraving and Etching: The Collection of Henry Graves Jr, saw a Dürer Adam and Eve reach US$10,000, a substantial figure in 1936 equivalent to nearly a quarter of a million dollars today.

The early years

Of course, he also collected watches. An early watch that anchors his horological story is almost modest in outward form. In the 1910s Patek Philippe built a 50 mm gold pocket watch with hours, minutes, subsidiary seconds and a power-reserve display. The movement went through the Geneva Observatory trials and received its rating certificate in 1920. After casing, the firm shipped it through an American retailer. Graves acquired it in 1925 and had his family coat of arms and motto, Esse Quam Videri, engraved on the back.

The papers remained with the watch, folded and creased over decades. In December 2010 that combination of movement, case, crest and documents resurfaced as Lot 79 in Christie’s New York sale and realised US$242,500, identified by specialists as the 16th Patek Philippe watch traced to Graves’ collection.

Patek Philippe No. 178’483, “Extra Special” delivered to Bailey, Banks and Biddle on October 14th, 1921. Image – Christies/collage

This gold observatory chronometer embodies the characteristics of precision and achievement that appealed to Graves. When Patek Philippe eventually compiled an internal list of watches made for Graves, the brand tallied 39 pieces delivered between 1922 and 1951. Among these 39 watches, a striking proportion were associated with Observatory trials and featured Guillaume balances or tourbillon regulators.

Graves’ art collection showed that he was a man who could appreciate decoration, but his fundamental requests to the workshops concerned performance. As such, the family coat of arms graces several movements that had already been tested in public competition.

Patek Philippe movement No. 97’589, manufactured in 1895, encased in wristwatch form in 1927. Collected by Henry Graves personally in Geneva on the June 16, 1928. Image – Christies/collage

At the same time, his interest in chiming watches materialised in wristwatch form. In 1927 he ordered a yellow gold minute repeater from Patek Philippe. It features a large tonneau case nearly 40 mm from lug to lug, and was among the first minute-repeating wristwatches the firm produced. On June 16, 1928, after a transatlantic crossing on the RMS Olympic, Graves walked into the salon at 41 rue du Rhône and collected it. A little more than 90 years later, in November 2019, Christie’s sold the watch for CHF4,575,000. These early acquisitions fueled Graves’ ambition as a collector.

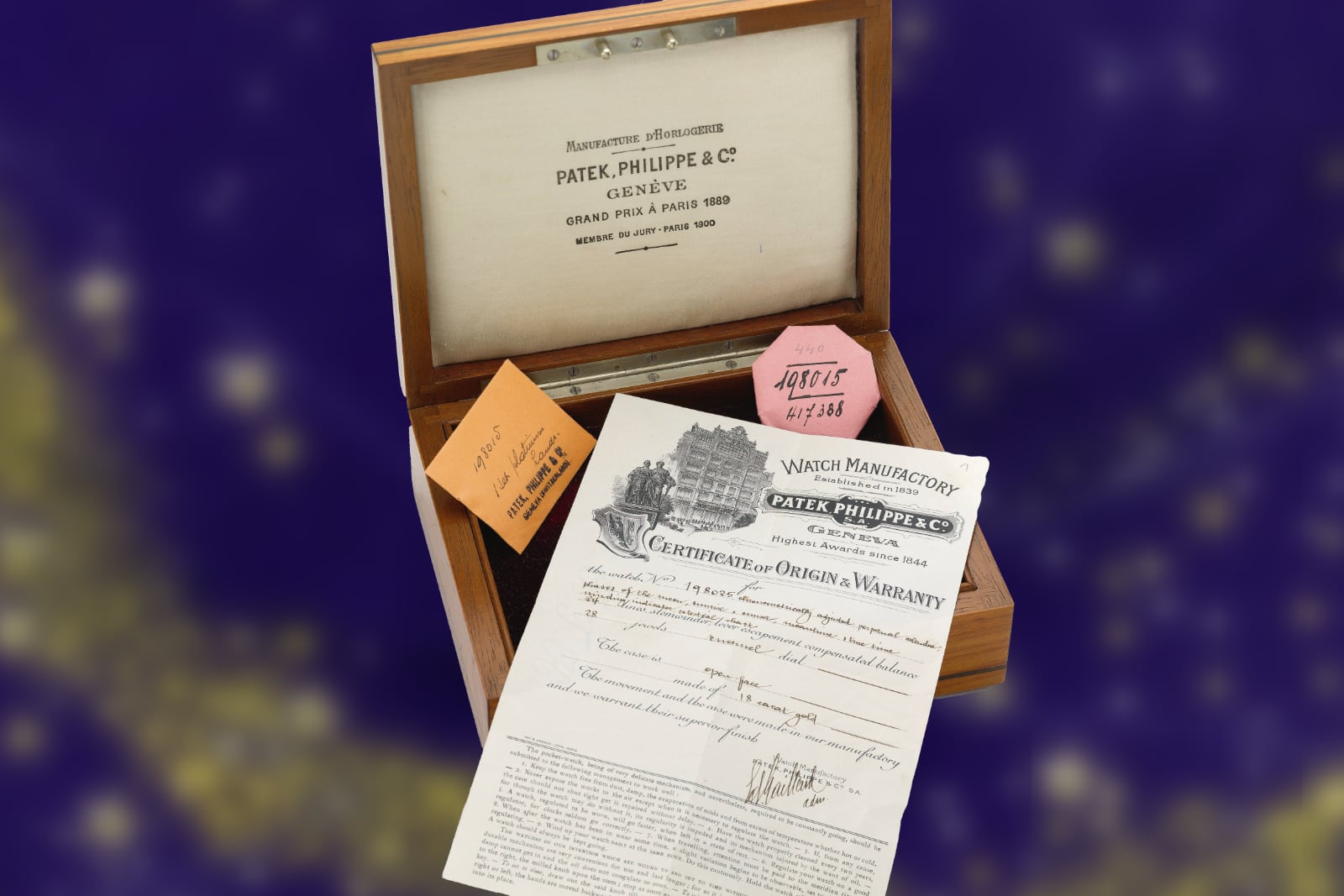

Even as production of the Supercomplication was consuming the specialists in the Vallée de Joux, other watches entered and left Graves’ orbit, including a keyless grand complication pocket watch with minute repeater, grande et petite sonnerie, perpetual calendar, split-seconds chronograph and moon phase. Decades later, the watch, along with its box and certificate, was discovered in a shoebox under his granddaughter’s bed. Sotheby’s and Christie’s treated it as a companion to the Supercomplication — its terrestrial twin with similar density packed into a more conventional format.

No. 198’052 acquired by Henry Graves in 1928 and later found in a shoebox. Image – Christies/collage

During those years, another American client occupied Patek Philippe’s order books: James Ward Packard, a noted engineer and automobile manufacturer. Packard commissioned a series of highly complicated pocket watches, some with as many as 16 complications, including sunrise, sunset and a star chart programmed for his hometown of Warren, Ohio. The experience gained making these watches proved vital when Graves later requested that Patek Philippe “plan and construct the most complicated watch, and in any case more complicated than Mr Packard’s”.

The story of a direct rivalry between the two men would only emerge later. In the 1990s, as Patek Philippe prepared anniversary books and Sotheby’s prepared the Time Museum sale, the idea of an “arms race” between Packard and Graves offered a neat way to dramatise the catalogue. As Alan Downing reports, Alan Banbery of Patek Philippe later acknowledged that he had been the source of the Packard–Graves rivalry story, originally floated in the early 1990s as a promotional narrative for the brand’s high complications and revived ahead of the 1999 sale of the Supercomplication. The archival record shows two separate client histories that overlap in time, yet never intersect in a way that suggests the two collectors maintained a conscious rivalry.

Esse Quam Videri

Around the same time, Patek Philippe reserved several of its Observatory prize-winning tourbillons for Graves. Movement 198’311, a 17-ligne tourbillon with a Guillaume balance and a cage by James Pellaton, took first prize in the 1933–34 Geneva Astronomical Observatory contest with 872.2 points, a record in its category. Cased in platinum with a bold Roman dial of the sort popular with American collectors, it was sold to Graves on July 29, 1935.

A similar watch with movement no. 198’427 surfaced at Christie’s Geneva in May 2004, complete with its observatory timing sheets and wooden box, hammering for CHF2,252,000. A third platinum tourbillon, movement no. 198’247, also ties back to Graves and, together with movement no. 198’310, now resides in the Patek Philippe Museum. Christie’s catalogues later pointed out that the only platinum tourbillon watches of this type known to exist were all made for Henry Graves Jr.

No. 198’311 tourbillon from 1932 with Guillaume balance and a polished steel three-arm tourbillon cage produced by James Pellaton. Image – Christies/collage

These platinum pieces form a clear picture of Graves’ mindset as a collector. Their visual language is sober: monochromatic dials, discreet signatures, and the family motto in small letters below a crest: Esse Quam Videri, which translates as ‘to be rather than to seem’. The contrast between invisible inner complexity and outward restraint fascinated the Christie’s specialists enough that they spelled the motto out in the lot notes, drawing a direct link between the Latin in the coat of arms and the aesthetic of the watches.

Missing pieces

Mystery surrounds a few of Graves’ other commissions, but the evidence that remains is tantalising. The most evocative absence is the ship’s bell watch. Research documents it as a grande sonnerie with a ship’s bell striking system, conceived as a thematic parallel to a similar piece produced for Packard. Its original presentation box, certificate of origin and spare crystal surfaced at Sotheby’s in a sale of Graves’ grandson’s estate, described in the catalogue with a careful note that the current whereabouts of the watch itself were unknown. Its movement and case numbers appear in the brand’s archives, yet the watch does not appear in any photographs or illustrations.

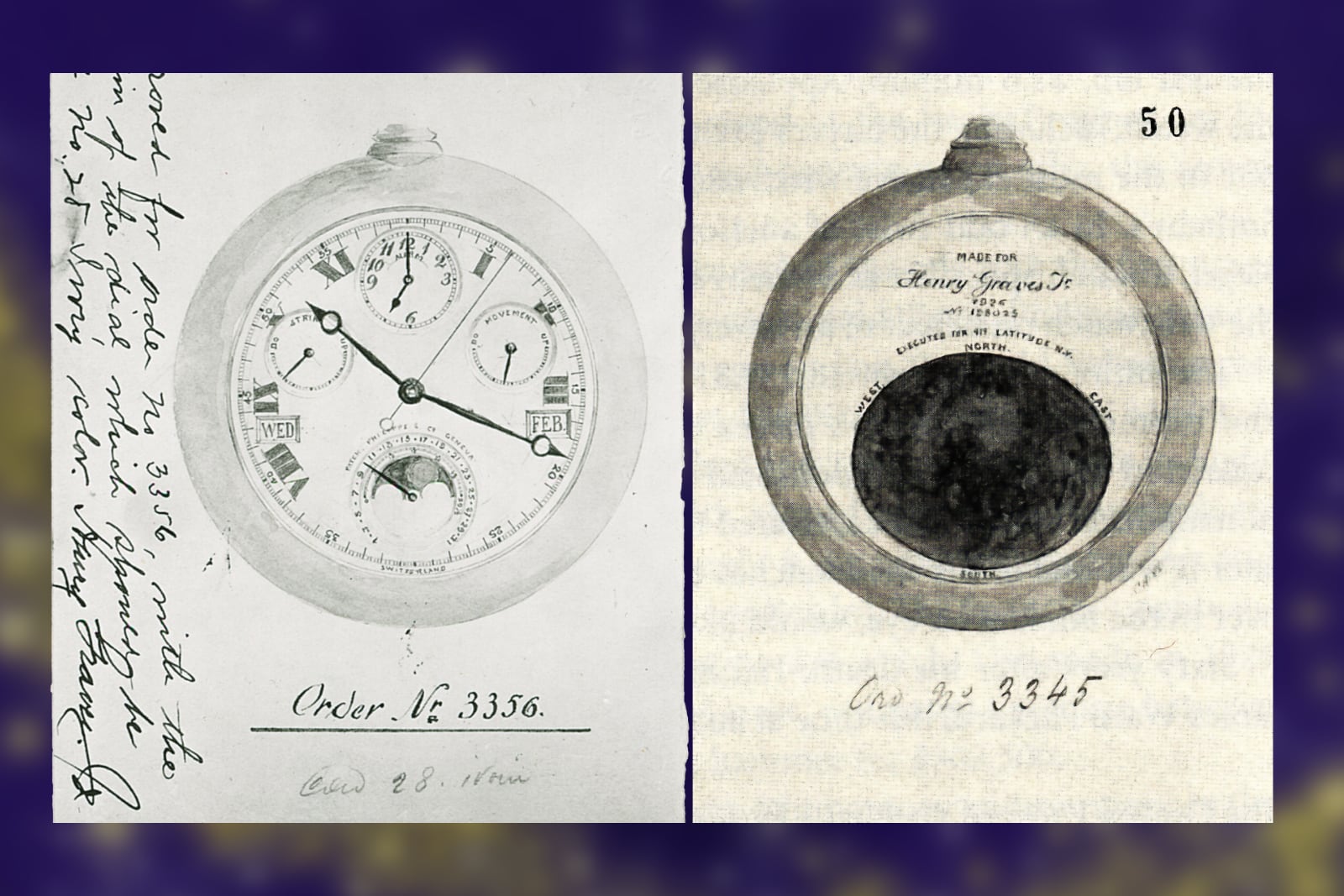

The mystery case revealing the existence of No. 198’015 and 198’025. Image – Sotheby’s/collage

Two more gaps share the same status. One concerns movement 198’025 with case 417’388, a platinum Observatory chronometer recorded in the factory books and in private archives for Henry Graves Jr, but with no secure public trace. The other is a “mystery” sky-chart watch, speculated by some writers to have been a second astronomical masterpiece, perhaps intended to accompany or follow the Supercomplication. Without a confirmed sighting or photograph, these mysterious commissions haunt the imaginations of scholars and collectors.

More mysteries. Image – Sotheby’s/collage

Interested parties

After Graves’ death in 1953, his various collections were dispersed. His Patek Philippe watches passed mainly to his daughter Gwendolen and his grandson Reginald H. “Pete” Fullerton Jr, while the art and prints moved through other auction channels. In January 1969, Patek Philippe wrote to Fullerton to say that another client had expressed interest in the Supercomplication and would be willing to pay a high price. Fullerton met the industrialist Seth Atwood in New York that February and showed him the Graves collection.

The sale was finalised a month later, making the Supercomplication one of the earliest major acquisitions for what would become the Time Museum in Rockford, Illinois. Atwood’s museum eventually expanded into a survey of 4,800 years of timekeeping, from Stonehenge to atomic clocks, with the Graves watch featured as a central exhibit. For almost three decades the Supercomplication sat in Rockford, occasionally studied by visiting specialists.

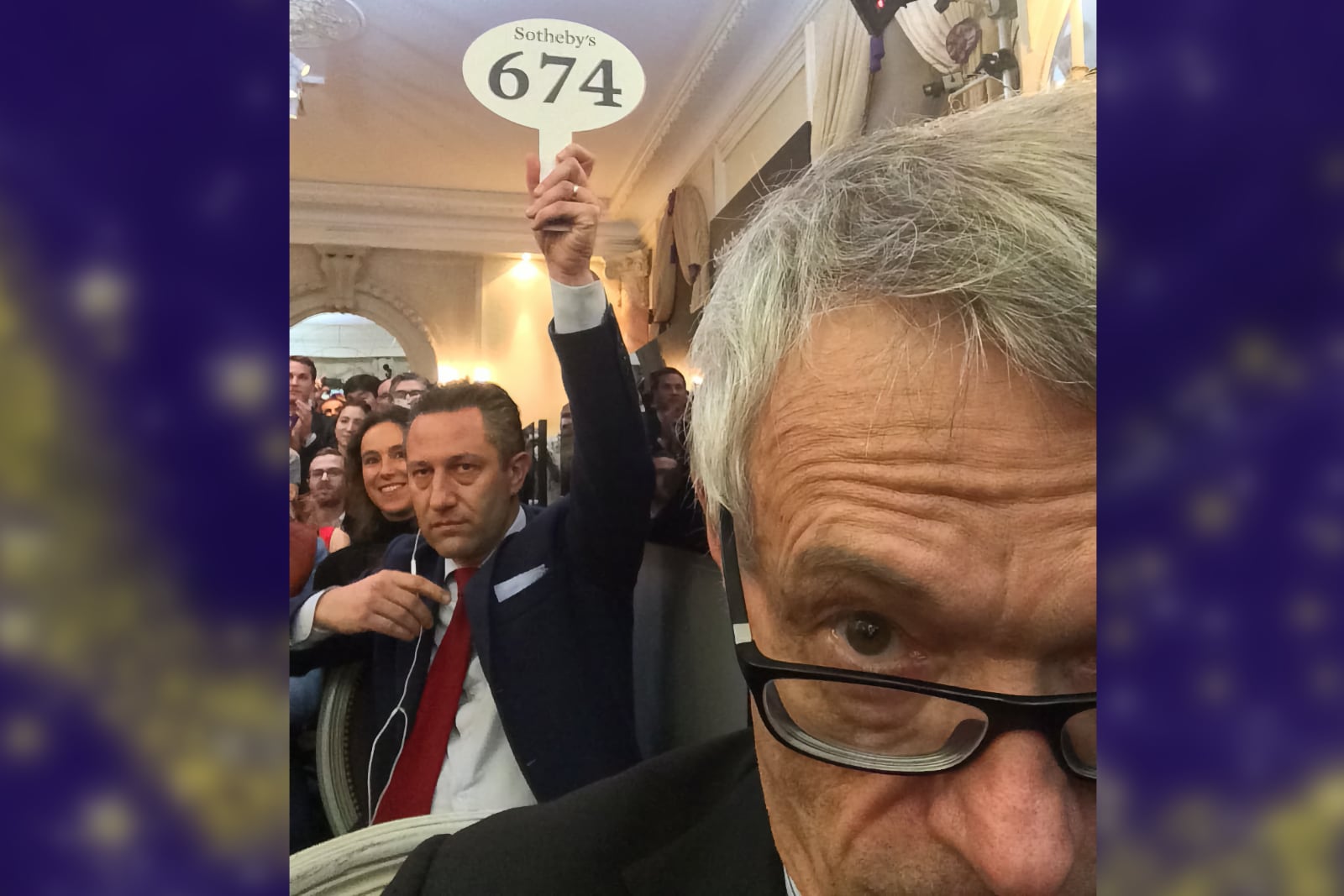

The New York Sotheby’s sale of the Henry Graves Supercomplication in 1999. Image – Sotheby’s

On March 12, 1999 the horological world learned that the Time Museum would close. Patricia Atwood announced that Sotheby’s would sell a group of masterworks, including the Graves Supercomplication. The sale, Masterpieces from the Time Museum, took place on December 2, 1999 in New York. Eighty-one lots crossed the block. Lot 7, the Supercomplication, entered the room with a low estimate of US$3 million dollars.

Bidding quickly eclipsed both low and high estimates — two phone bidders didn’t even bother joining the fray until the high estimate of US$5 million had been reached. When the hammer fell, the price stood at US$11,002,500, a world record for any horological object. The sale total reached US$28 million, four times the low estimate, establishing several records at once and fixing the Graves watch in the public imagination as the most expensive watch ever sold.

Movement No. 191’434, First Prize Observatory chronometer delivered to Henry Graves in 1927. Image – Sotheby’s/collage

Around the same period, other Graves pieces began to surface. The keyless grand complication appeared in the early 2000s, its discovery in a shoebox providing a useful human detail for the catalogue. The platinum tourbillons emerged at Christie’s Geneva in 2004 and 2008, with descriptions that emphasised their observatory history and the Graves family’s motto on the back.

Meanwhile, the Supercomplication followed a path that eventually linked it to another collecting dynasty. The anonymous buyer of 1999 was later identified as Sheikh Saud bin Mohammed Al-Thani of Qatar, a central figure in that country’s museum-building programme and one of the most active buyers of art and artefacts of his generation.

As financial pressures mounted, he pledged several pieces, including the Supercomplication, to Sotheby’s Financial Services. After his death in 2014, the watch returned to the auction room in Geneva. On November 11 2014, Sotheby’s offered it again; bidding carried it to CHF23,237,000, roughly US$24 million at the time, once again setting a world record for a watch at auction.

Paddle no. 674 in the hands of Aurel Bacs bidding the Henry Graves Supercomplication for 23,237,000 Swiss francs. A moment immortalised by Dr. Crott in a now famous “selfie” Image – Dr. Helmut Crott

The 2014 sale coincided with a different kind of attention in the Vallée de Joux. The Espace Horloger in Le Sentier mounted a “Star Watch” exhibition devoted to the Supercomplication and the people who built it. Philippe Dufour spent time with the watch for a 3D film, opening the case and tracing the path of its levers for the camera. It was a rare moment when local craft and global market spectacle met around a single object. For the village that had hosted the Piguet and Rochat families, the watch became a mirror of its own history.

The Graves legacy

Through all of this, the sky above Central Park has stayed the same. The skyline along Fifth Avenue has shifted over the decades; 834 has seen new owners and new furnishings. The family’s estate on Eagle Island has passed through the Girl Scouts and into the care of preservation groups who invoke Graves as a benefactor and as a symbol of a gentler sort of privilege. The watches themselves have also moved on: some returned home to Geneva where they are on display in the Patek Philippe Museum, while others disappeared into private safes. A few others might exist, but there’s little more than paperwork to prove it.

The Henry Graves Supercomplication Sky Chart depicting the sky over 834 Fifth Avenue in New York. Image – Sothebys

Looked at as a whole, the Graves collection resembles a night sky: bright points where provenance is secure, dim clusters where information is incomplete, and a handful of dark spaces where something significant might have once shone but has since slipped from view. The Supercomplication stands at the centre of that map, a mechanical image of the very sky that hangs above 834 Fifth Avenue and the streets below. Its star chart remembers where Graves lived and what he asked his watchmakers to do: fold his world, and his sky, into wheels and springs. The watches that remain, and the watches that have gone missing, all circle that decision.

Back to top.