Complicated Collectors: John Pierpont Morgan

J.P. Morgan and the history of European horology

As part of a continuing series on great watch collectors, following the first studies dedicated to Elliott Cabot Lee and Thomas Engel, the third instalment turns to the horological world of John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (1837-1913). Based on the famous 1912 Chiswick Press catalogue, this analysis reflects the range and typological structure of his collection. These watches span devotional and allegorical forms, astronomical instruments, and multi-functional works of mechanical synthesis.

While Morgan’s approach has sometimes been described as encyclopaedic rather than selective, the collection itself tells a different story, one in which historical resonance and technical refinement consistently overlap. The selection offers a tangible expression of Morgan’s collecting logic, in which cultural meaning, mechanical ingenuity, and symbolic intent were sought in equal measure.

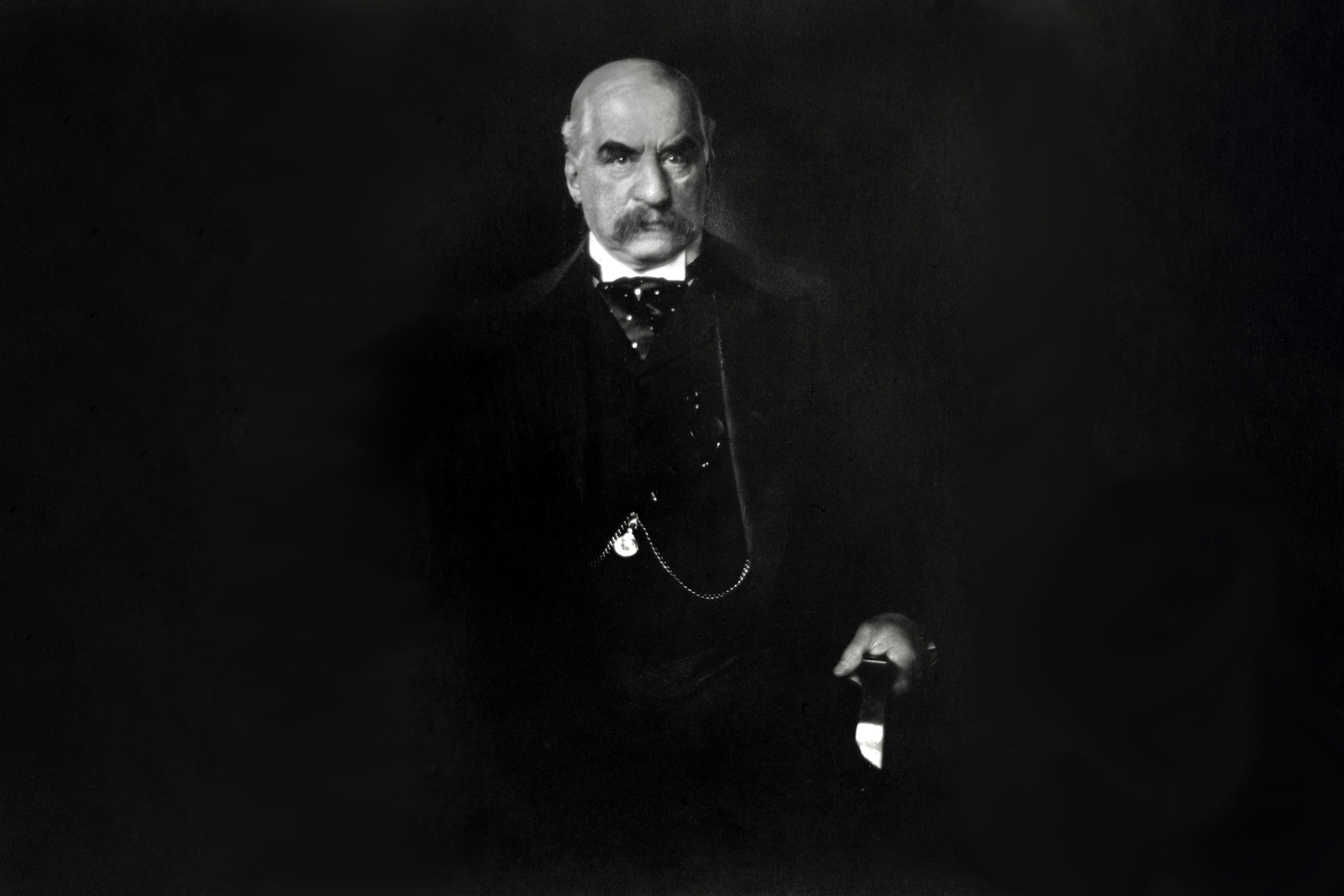

The man

In the pantheon of American capitalists, J. Pierpont Morgan occupies a singular place: titan of industry, consolidator of empires, and paradoxically, one of the greatest cultural preservationists of his age. Born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1837, the son of an ambitious transatlantic banker, he came of age amid the expanding architecture of American finance.

His education, from early childhood, was European. He studied in Switzerland and later in Germany, where a brief period at the University of Göttingen introduced him to the German language and the foundations of art history. These formative years abroad left a lasting impression, nurturing an affinity for the past that would become central to his intellectual life and collecting temperament.

Publicly, Morgan was cast in steel and steam. He orchestrated the reorganisation of American railroads, brokered the creation of U.S. Steel, and stabilised markets during the Panic of 1907 with such authority that for a time he stood above the state itself. He was famously imposing, physically and in terms of presence.

But beneath the glint of power lay a private man of subtler and more enduring pursuits. His character, as remembered by contemporaries, was less imperial than monastic. He lived in sparse personal quarters, detested ostentation, and surrounded himself with books, artworks, and ecclesiastical artefacts arranged with the discipline of a museum.

Some of Morgan’s collections are on show at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, now a museum open to the public

His collecting began early, first with autographs and rare books, before expanding into paintings, sculpture, and the decorative arts. Watches came later, but were embraced with the same intensity and system. To those outside his circle, he appeared as a figure of remote grandeur; to those within it, he revealed a temperament marked by warmth and sharp, unaffected wit. The two aspects coexisted without tension.

His passion for objects matched the depth of his command of capital, guided by intent and a clear sense of purpose. He collected as one might build a library: with logic, narrative ambition, and a sense of cultural duty. “Everything I own,” he once told a friend, “belongs to the American people,” and by the time of his death, more than 7,000 objects, many of them among the finest of their kind, had entered the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

That legacy was anything but improvised. Morgan’s approach to collecting was governed by structure and permanence. He acquired with the intent to preserve, documented with scholarly care, and donated with a vision for institutional memory. Where others saw trophies, he saw typologies; where others prized fashion, he valued continuity.

Some later commentators have misunderstood this as indifference to quality, yet the collection reveals the opposite: works of exceptional craftsmanship were selected precisely because they embodied technical or symbolic milestones. In the words of European horologists who observed his acquisitions with both admiration and regret, Morgan was described as a custodian, a man who “collected as if history were his inheritance and legacy his responsibility.”

The collector

Morgan’s collecting impulse favoured completion over display. His temperament lent itself to systems, and in collecting, as in banking, he gravitated toward structure rather than spectacle. Watches held meaning for him as expressions of mechanical philosophy, portable artefacts in which time, craftsmanship, and civilisation converged. By the early 20th century, he was acquiring them with characteristic rigour, focusing on entire collections rather than isolated pieces, and privileging typologies over trends.

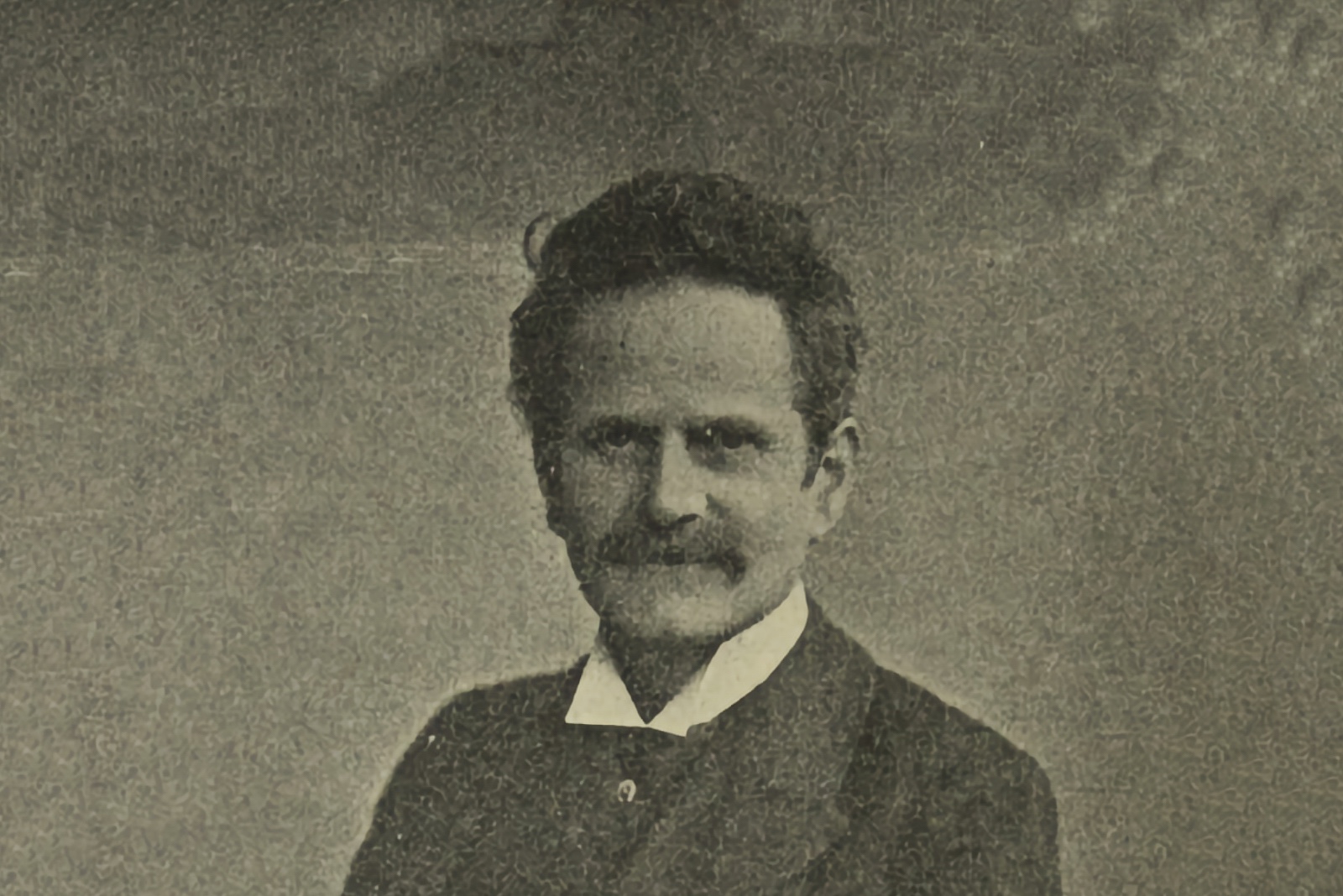

Heinrich Marfels (1854-1929). Image – Wikipedia

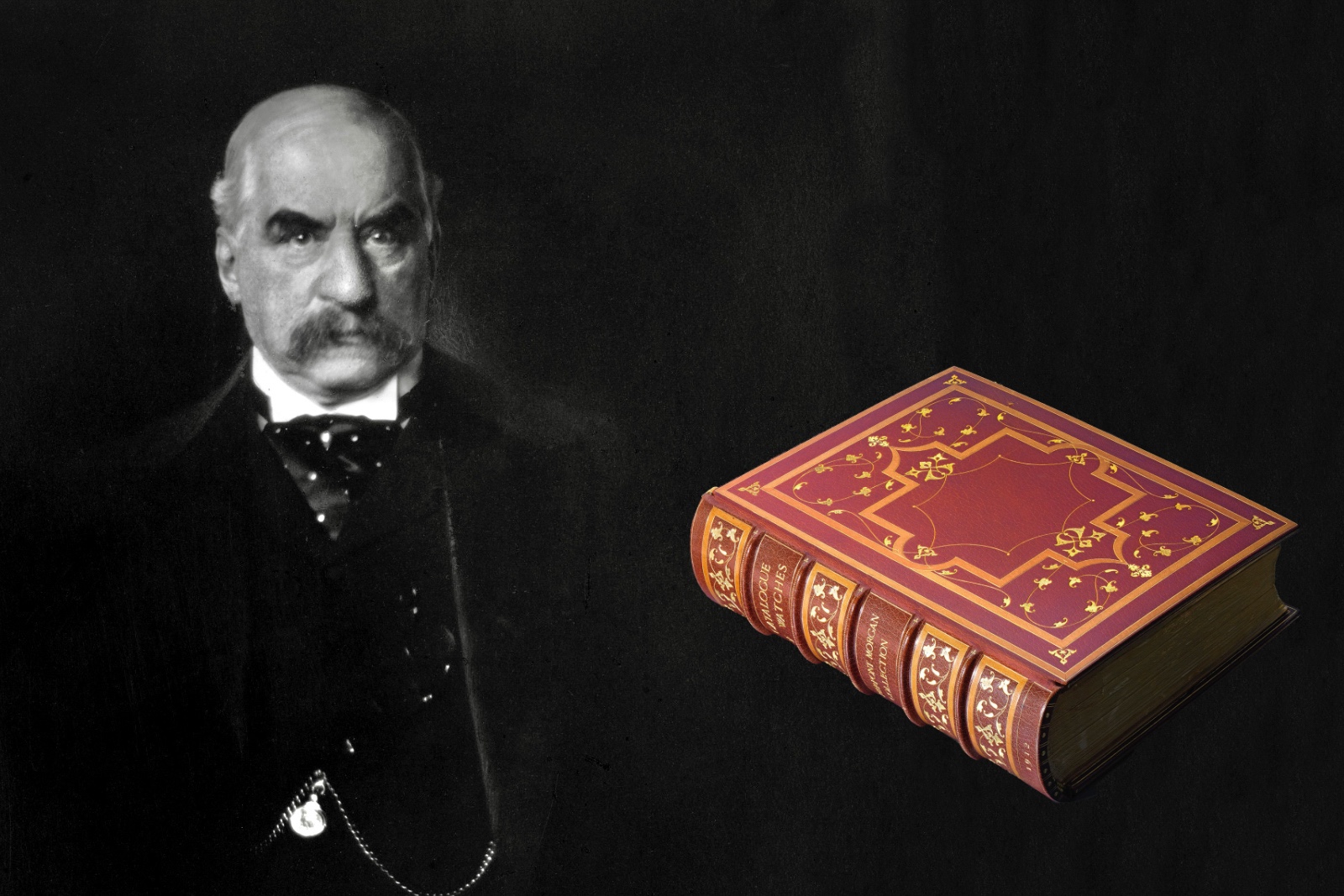

Two landmark acquisitions defined the core of Morgan’s horological holdings: the collections of Carl Heinrich Marfels and F. G. Hilton Price.

The Marfels purchase occurred in two stages, as reported in both German and French trade journals. The first tranche, comprising around forty watches, was acquired in September 1909 for 750,000 francs. The second, in early 1910, added eighty more for 1,875,000 francs. Combined, they represented one of the most ambitious and costly horological acquisitions ever undertaken by a private individual.

Contemporary German and Swiss commentators spoke openly of a cultural loss, noting that their finest domestic pieces had crossed the Atlantic to what one journal called “the land of the dollar kings.” Marfels had been a prominent and affluent dealer, but his asking price exceeded what any German museum could afford. Morgan alone met it, and did so decisively.

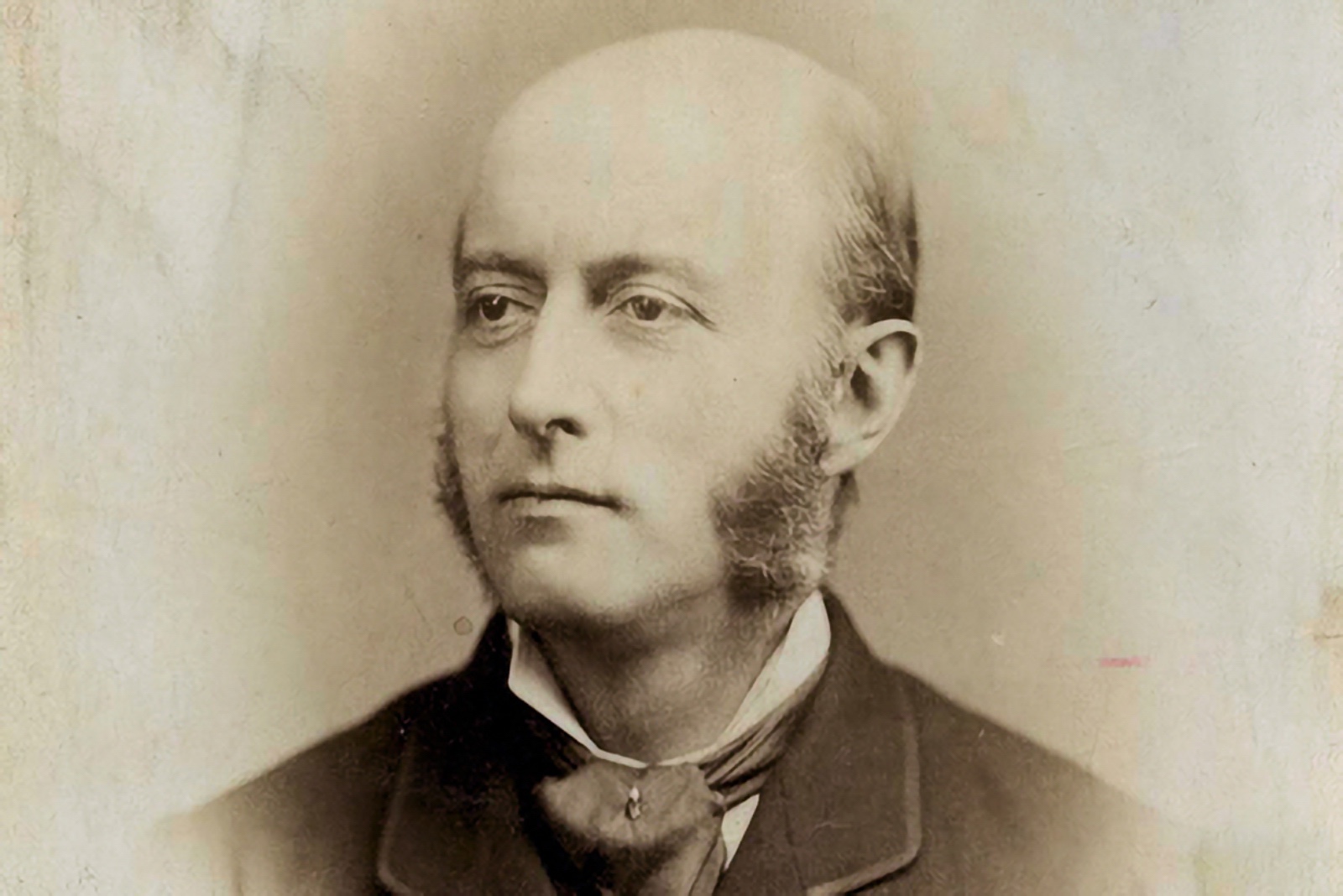

Frederick George Hilton Price (1842-1909). Image – Wikipedia

The Hilton Price acquisition, sold privately in London following the collector’s death in 1909, introduced another significant body of Renaissance and early English watches into Morgan’s holdings. It included works by David Ramsay, Nicholas Vallin, and members of the Cuper family.

The Marfels and Hilton Price collections gave Morgan’s horological project its shape, a foundation from which to trace a historical arc through form, function, and purpose. These were watches of scientific ambition and devotional complexity: rock crystal pendant pieces, enamelled allegories, and table clocks with astronomical dials, all selected with an eye toward continuity and mechanical significance. Instead of rarities or novelties, Morgan pursued categories, building what one German obituary described as “every essential phase of watchmaking history.”

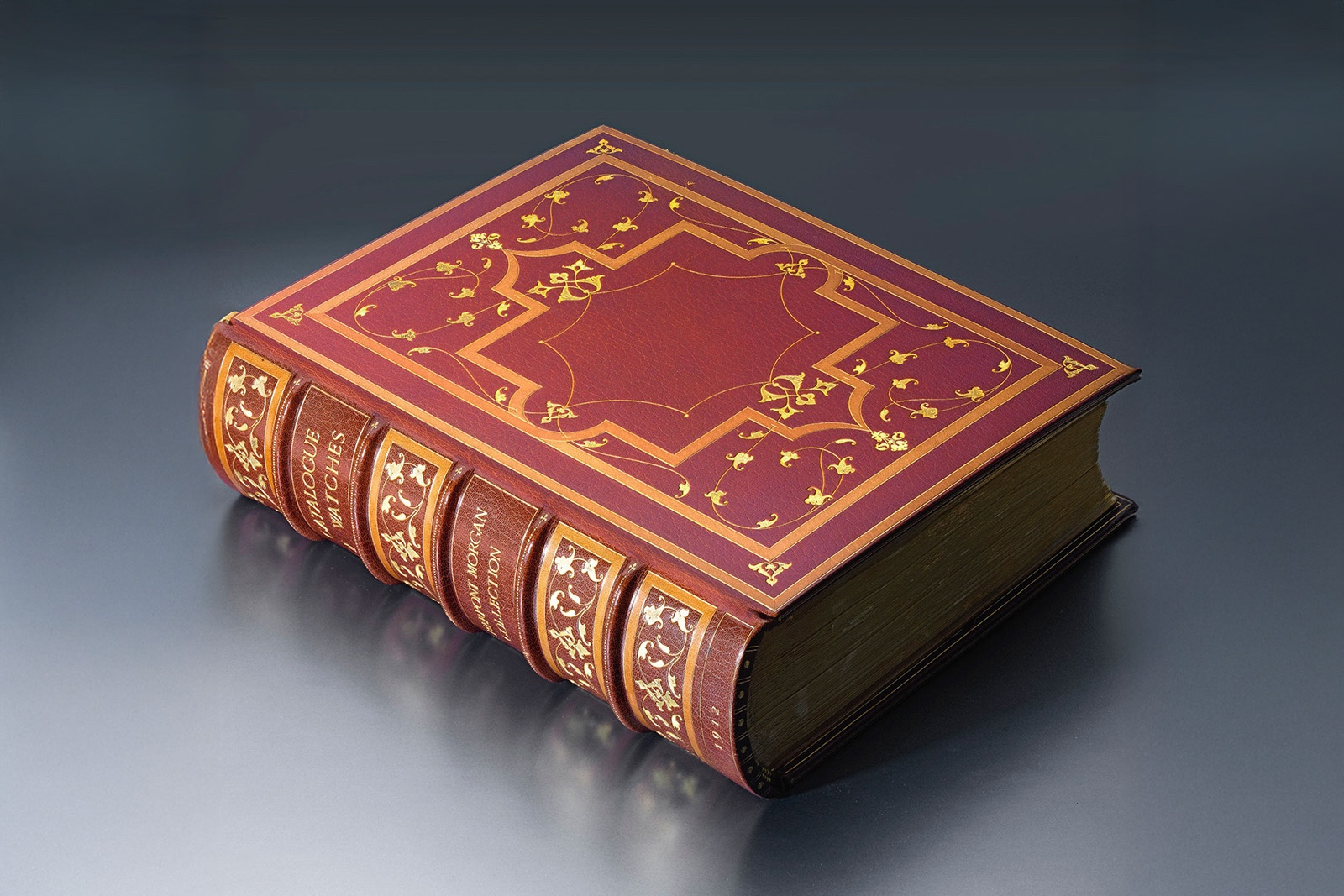

What distinguished his approach was the scholarly infrastructure that followed. In 1912, he commissioned a private catalogue of the collection, masterfully printed by the Chiswick Press in London and authored by art historian George Charles Williamson. For collectors of horology or bibliographic rarities, this vellum-bound volume remains a landmark. Though not essential for reference today, the book is highly desirable as an object, an example of early 20th-century scholarly printing at its finest.

Bound in vellum with gilded edges and hand-painted plates – and weighing some 6 kg – the catalogue was conceived as a cultural document. It organised the collection both chronologically and typologically, pairing technical detail with iconographic commentary. Across Europe, it was praised as a bibliographic achievement. By the mid-1920s, journals such as Deutsche Uhrmacher-Zeitung and the Allgemeines Journal der Uhrmacherkunst were citing it as a reference, even if few of their readers had seen the watches it described.

Commentators of the period were consistent in their view: Morgan had assembled the most significant private watch collection of his generation. Retrospectives published in 1912, 1913, 1924, and again in 1929 described the collection as encyclopaedic, coherent, and shaped by intellectual ambition.

His 1913 obituary in Deutsche Uhrmacher-Zeitung referred to him as “a guardian of horological culture,” whose holdings extended “from the Gothic to the Industrial Age,” and whose intention was “nothing less than a monument to human ingenuity in timekeeping.” By 1924, the same journal named him “the last of the true encyclopaedic collectors,” likening his methods to those of the Enlightenment savants who assembled collections as instruments of historical understanding.

The 1912 catalogue documents 16th-century rock crystal pendant watches, skull- and cross-shaped devotional pieces, astronomical timekeepers with planetary gearing, enameled cases from Blois and Augsburg, and technical masterpieces by British makers. At the centre stood the most intellectually demanding objects in the collection: astronomical and calendar watches that distilled scientific models into portable instruments, collapsing the cosmos into miniature, mechanical form.

Important German collectors: Ernst von Bassermann-Jordan, Carl Heinrich Marfels, Wilhelm Triebold and Max Engelmann. Image – DGC Freunde Alter Uhren, nº XV 1976. Image – Bayerisches Nationalmuseum.

By the time of his death in 1913, the collection had grown to several hundred watches, most of which were transferred to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1917 by his son, John Pierpont Morgan Jr., better known as Jack Morgan, who was a collector in his own right. That gift, part of a broader act of cultural philanthropy comprising more than 7,000 objects, helped establish the museum’s Department of Western Art, where many of the clocks and watches are still held. The transfer reflected Morgan’s belief that private taste was, in the end, best served by public memory. It preserved the integrity of the collection, ensuring that the watches would remain together, catalogued, studied, and periodically exhibited.

To write of Morgan as a collector is to describe a man who applied the logic of systems to the poetics of time. His horological pursuits were archival, architectural, and openly didactic. In an age increasingly defined by speed and spectacle, he constructed a chronology of slowness, watches conceived for contemplation rather than wear. His legacy departed from the fashions of his contemporaries, guided instead by structure, discipline, and a view toward permanence. Morgan approached the past as something to be preserved through intention and craft, assembling a collection that continues to instruct long after its completion.

The collection

The watches Morgan assembled span three centuries of European horology, from the early Renaissance to the threshold of industrial standardisation. Within that span lies a clear sequence: devotional and rock crystal timepieces from the German-speaking world, allegorical and enamelled works from Blois and Geneva, English watches of technical sophistication, and astronomical complications of remarkable ambition. Each segment reflects a different intersection of mechanical ingenuity and cultural symbolism, all shaped by a broader logic of typological completeness. Morgan selected examples that traced lineage, how form, function, and meaning developed across time.

The earliest watches in the collection include sixteenth-century pendant types with Gothic and Mannerist features: drum-shaped cases, Latin inscriptions, and rock crystal chambers with fire-gilded movement plates. These are followed by cross- and skull-shaped pieces, combining religious symbolism with early escapement technology. The materials, silver, rock crystal, champlevé enamel, convey both austerity and wonder, and their inclusion within the collection reflects Morgan’s interest in horology’s origins as a union of mechanical invention and spiritual expression.

Devotional and form watches

Among the most symbolically charged works in Morgan’s collection are the devotional and form watches, objects shaped as crosses, skulls, or miniature ecclesiastical forms, conceived as instruments of time and moral reflection. These belonged to an era when horology was intimately tied to religious contemplation. Crafted in silver-gilt, rock crystal, and enamel, and often engraved with biblical passages, Passion motifs, or memento mori inscriptions, they fused visual devotion with mechanical order.

Rock crystal cross-shaped pendant watch, C. Cusin, circa 1580–1600. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Catalogue, p. 4, Plate III)

One of the earliest and most architecturally structured examples is a rock crystal cross-shaped pendant watch made around 1580-1600 by Charles Cusin of Autun. Set in a clear rock-crystal case with a bevelled cover, the movement is signed “C. Cusin.” The face is richly engraved in the style of Etienne Delaune with religious scenes: above the dial circle are clouds with letters, below is Christ bearing His cross, and on either side are emblems of the Passion including the skull, dice, chalice, hammer, pincers, and ladders. The case and lid are bordered with silver engraved with leaves and foliage.

Cruciform watch, Lyon, circa 1600, attributed to Pierre Combret of Lyon. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Catalogue, p. 24, Plate XIII)

A similarly complex example is a cruciform metal watch attributed to Pierre Combret of Lyon, dated circa 1600. The stackfreed movement is signed “Pierre Combret a Lyon” and features a balance cock pinned on with ratchet adjustment. The metal case is richly engraved in the style of Etienne Delaune, with the front showing the Crucifixion in the centre, the Virgin and St. John on either side, the Dove of the Holy Spirit above, and the Agnus Dei below. The back depicts the Virgin and Child with saints, possibly representing the four Evangelists.

Silver skull-form watch, Blois, circa 1600, attributed to Isaac Penard of Blois. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Catalogue, p. 13, Plate VIII)

The skull-form tradition is represented by a silver watch attributed to Isaac Penard of Blois, made circa 1600. The dial is hidden beneath a hinged jaw formed by the central teeth. The surface is engraved with floral ornaments and a rose motif at the centre, bordered by black-inked numerals. The design draws on the memento mori tradition, inviting the wearer to contemplate time as both a measure and a form of existential reckoning.

Rock crystal cross-shaped watch by Anthony Arlaud of Maringues, circa 1600. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Catalogue, p. 28, Plate XIV)

Another devotional example is the cross-shaped watch by Anthony Arlaud of Maringues, circa 1600. The movement is signed “Anthonie Arlaud” and the case is entirely of clear rock-crystal mounted in metal-work. The face features chased metal-work with a silver hour dial, and the decoration below represents Christ rising from the tomb, with the cock above and emblems of the Passion on either side. The centre of the hour dial shows a landscape with a shepherd and his sheep.

Although these watches entered the collection through earlier acquisitions, Morgan recognised their place within horology’s devotional origins. He regarded them as essential entries in the chronology of European watchmaking, positioned at the intersection of private devotion and early portable technology, where mechanical movement supports the architecture of belief.

Scientific and astronomical watches

Within Morgan’s collection, a smaller but intellectually concentrated group of watches explores the alignment between horology and the observation of natural phenomena. Works designed to articulate the structure of time through astronomical, calendrical, and symbolic systems. Whether configured as planetary models, seasonal indicators, or mechanical calendars, they reflect a view of time governed by celestial rhythm and made legible through intricate design.

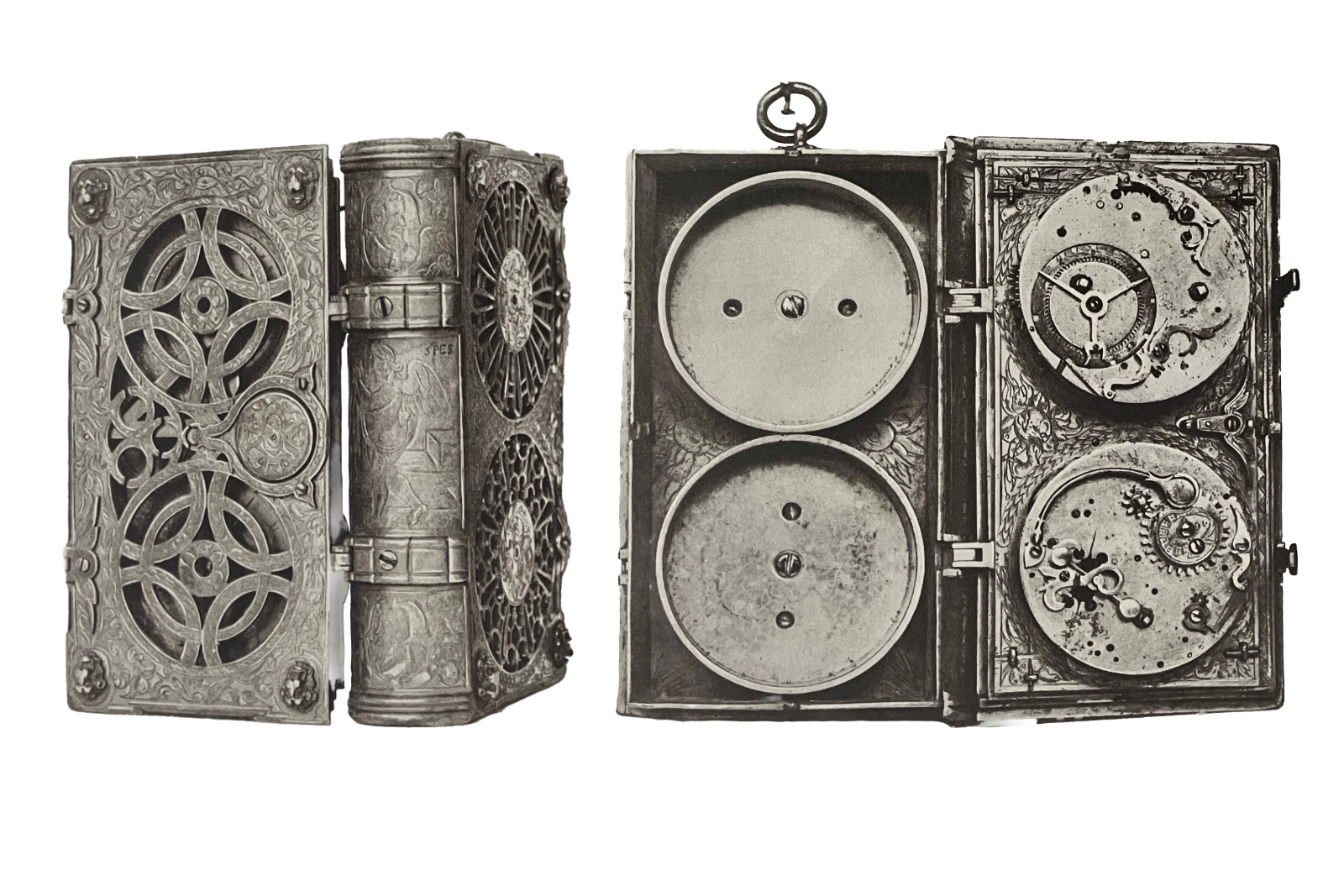

Book-shaped astronomical watch by Hans Schnier, Spires, late 16th century, with two movements, sundial, compass, and lunar indications. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Plates LII and LIII)

Among the most mechanically ambitious pieces is the very large book-shaped watch from Spires by Hans Schnier. This exceptional timepiece bears Schnier’s signature and initials, with portraits believed to represent Emperor Rudolph II and his mother, Maria of Austria. The watch features two separate movements, one with an alarm, and includes in the interior of its lid a sundial, compass, and geometrical dials for recording the age and phases of the moon, the months, and other astronomical divisions. The movement retains its original stackfreed and foliot.

Oval astronomical watch by David Ramsay, London, 1610–1625, with zodiac, planetary and lunar indicators, enamel by Reymond school. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Plate LIX)

David Ramsay’s very remarkable oval watch represents another pinnacle of astronomical complexity. This London-made timepiece, dating from between 1610 and 1625, features complex dials indicating hours, months, days of the month, days of the week, signs of the zodiac, movements of the planets, and the ages and phases of the moon. The enamel work is signed by one of the members of the Reymond family, making it both an important portable timekeeper and an example of Limoges enamel decoration.

Silver calendar watch by Thomas Alcock, London, circa 1635, with moon-phase disc and star-studded dial. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Plate LXIII)

Johan Bock’s egg-shaped watch from Frankfurt, circa 1620, demonstrates German astronomical craftsmanship. The movement is signed “Johan Bock, Franckfort” and features two silvered numeral rings, one for hours and another for days of the month, plus a small circular dial with its own hand giving the days of the week, and two small openings showing the movements of the moon and the signs of the zodiac. The exterior is silvered and depicts Queen Esther before King Ahasuerus.

Silver calendar watch by Thomas Alcock, London, circa 1635, with moon-phase disc and star-studded dial. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Plate LXIII)

Thomas Alcock’s circular silver double-case calendar watch from London, circa 1635, represents the English contribution to scientific horology. The dial is an exceedingly fine example of engraved silver indicating the ages and phases of the moon by means of a central rotating disk, and the day of the month by a rotating ring outside the hour band. The centre is semé with silver stars on a black ground, creating both mechanical precision and visual poetry.

These astronomical and calendar watches demonstrate Morgan’s appreciation for timepieces that functioned as portable observatories, instruments that collapsed the complexity of celestial mechanics into personal, wearable form. They represent horology’s highest intellectual ambitions, where the measurement of time served both practical and philosophical purposes.

Allegorical, devotional, and painted watches

The decorative watches in Morgan’s collection preserved iconographic languages and narrative forms that had passed from the hands of manuscript painters to the new surface of portable time. From as early as the 16th century, enamellers working in Blois, Lyon, and Geneva created miniature compositions that rivalled painted panels in complexity and intent. These watches integrated mechanism with theological, literary, or mythological imagery, forming objects in which timekeeping and representation were joined by design.

Enamelled watch with Judgement of Paris scene, by G. Gamod. Plate XX – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue Enamelled watch with scenes from classical mythology, by Auguste Bretoneau. Plate XV – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue Watch with enamel decoration from Greco-Roman mythology, by Nicholas Gribelin the Younger. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Plate XXII)

Morgan’s holdings included several such examples, notably works by the Gribelin and Vauquer families of Blois, whose enamelled surfaces drew from religious and classical sources.

The death’s head watch by Isaac Penard, for instance, presents a stark memento mori in silver, with a hinged jaw concealing the dial, an object of personal reflection as well as precision (Catalogue, p. 13, Plate VIII). Other examples depict scenes from the Old Testament and Greco-Roman mythology: the Judgement of Paris, Antony and Cleopatra, the Calydonian Boar hunt, subjects rendered by G. Gamod (Plate XX), Auguste Bretoneau (Plate XV), and Nicholas Gribelin the younger (Plate XXII) (Catalogue, pp. 38–48).

Shell-shaped enamelled watch with symbolic decoration, by Gribelin of Blois. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Plate XXI)

Although many of these watches entered the collection through the Hilton Price acquisition, they served as essential anchors in Morgan’s historical framework. Their presence acknowledged horology’s early alignment with sacred and allegorical meaning. Shell-shaped cases, monstrance forms, and topaz-mounted frames, such as the enamelled watch by Gribelin (Catalogue, p. 48, Plate XXI) or the rock crystal and gold piece by Jean Hubert of Rouen (Catalogue, p. 76, Plate XXXI), illustrate the multiple functions of these objects as gifts, devotional artefacts, or instruments of courtly display.

Even when the movements lacked technical completeness, the cases retained their full documentary value. Morgan recognised these watches as part of horology’s cultural infrastructure. To chart the evolution of watchmaking without them would be to leave its visual and symbolic history unexamined. The painted watch, in this context, served as both mechanism and message, a record of artistic languages embedded in time.

English horology and the architecture of precision

Within the broader framework of Morgan’s collection, English watches held a distinct position. They reflected a tradition defined by technical refinement, chronometric ambition, and a restrained visual language grounded in geometry and proportion. While French and Swiss makers frequently pursued embellishment, the English school favoured structure, legibility, and regulated accuracy. Morgan’s preference for this tradition aligned with his appreciation for systems, both mechanical and institutional, and with his Anglo-American cultural position.

Double-case silver watch by Daniel Quare, London, circa 1690, with engraved silver dial and piqué leather outer case. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Plate LXXIII)

The catalogue includes multiple examples from London workshops active in the 17th and 18th centuries. Daniel Quare, dated circa 1690, is represented by a double-case silver watch with movement signed “D. Quare, London.” The inner case is plain silver; the outer is covered in reddish-brown leather piqué with gold and silver studs. The engraved silver dial includes inner and outer rings for hours and minutes, maintaining formal clarity within a decorative setting. The design reflects the principles of late 17th-century English domestic production: structurally robust, legible, and balanced.

Large silver travelling clock-watch with alarum, rotating month dial, pierced floral case, by Thomas Tompion. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Plate LXXI)

Thomas Tompion, often regarded as the father of English watchmaking, is represented in the collection by several examples. Among them, his unusually large silver travelling clock-watch with alarum, signed “Thos. Tompion, London,” exemplifies the sophistication of English horology at the close of the 17th century. The dial is engraved in silver and features a central rotating disc to indicate the months, with its own hand, surrounded by three winding squares positioned beyond the month ring. The case is distinguished by large pierced openings engraved with floral designs, while the back of the movement reveals complex and richly executed work, including a boldly engraved cock.

Melon-shaped silver watch with engraved foliage and river scene dial, retaining original key, by Edward East. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Plate LXII)

Edward East, a prominent maker of the previous generation, is represented by several watches (Nos. 134, 135, 137). Watch No. 137 features a melon-shaped silver case divided into engraved segments, each filled with stylised foliage. The silver dial includes an engraved river scene and retains its original jointed key, attached by a steel chain. This was a form East favoured for his smaller pocket watches, and one that Charles II is said to have used when wagering at pall-mall.

Though quieter in ornament than their Continental counterparts, these watches express a different kind of ambition. They present a philosophy of construction in which function governs form and clarity sustains elegance. In collecting them, Morgan reaffirmed the place of English horology within the historical arc he sought to preserve, an arc grounded in precision, coherence, and continuity.

Mechanisms of synthesis and the late mechanical age

The later segment of Morgan’s collection reflects a period in which technical layering became an expressive principle in its own right. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, watchmakers fused functions, chiming mechanisms, musical trains, automata, and calendar work, into unified mechanical programmes. These timepieces reveal a matured mechanical intelligence, where invention advances tradition, and complexity affirms mastery through integration and refinement.

Gold repeater and musical watch, circa 1800, with enamel portrait of Napoleon and pearl-set bezel. Unsigned. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Plate XXIX)

Among the most sophisticated examples is an unsigned circular gold repeater and musical watch, circa 1800. The movement is configured to play a tune at the top of each hour and to repeat the hours and quarters on demand. The inner case bears engraved instructions “Musique. Montre. Aiguilles” with arrows indicating the winding directions for music, movement, and hands. The dial is entirely of engraved gold with burnished numerals; the back shows a finely executed enamel portrait of Napoleon, framed by a border of large pearls that also surrounds the dial. The bow is richly ornamented with additional pearls. The watch was reportedly presented by Napoleon to Murat after the Battle of Marengo in 1800.

Gold box watch, circa 1700, with triple dials, automaton, and enamelled scenes. Unsigned. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Plate XL)

An even more elaborate synthesis appears in a rectangular gold box (circa 1700) that opens in three hinged divisions. The centre serves as a compartment, the right contains a watch with three dials, two in white enamel for hours and minutes, a third in copper for seconds, while the left houses a musical movement with automaton figures: a shepherdess tending sheep beside a water wheel. The exterior is decorated with enamel scenes of pastoral and mythological character, framed by rows of pearls.

Metal repeater and calendar watch by N. Vallin, London, circa 1635, with pierced case and month indication. Image – J.P. Morgan Watch Catalogue (Plates LXV and LXVI)

Calendar complications provide a more restrained but equally thoughtful form of synthesis. The circular metal repeater watch by N. Vallin of London (No. 144) demonstrates the integration of chiming and calendar functions within a single mechanism. The movement is signed “N. Vallin at London” and features both repeating capability and calendar complications. The dial displays a silvered hour ring with a separate silver ring denoting the months, the centre decorated with flowers and leaves. The case is of remarkable excellence, wholly of metal, richly engraved and pierced, with the lid perforated to reveal the face.

In these works, Morgan’s vision reaches its most intricate expression: time measured through deliberate layering of function and meaning. These final pieces selected from the collection demonstrate how technical mastery could serve utility and aesthetic ambition alike, objects conceived as instruments, artworks, and enduring symbols of human ingenuity.

Conclusion

J.P. Morgan Sr.’s watch collection was shaped by a temperament that valued structure over impression, lineage over novelty, and continuity over interruption. It followed no passing trend and responded to no market imperative. Its coherence emerged from the careful accumulation of forms, functions, and meanings drawn from three centuries of European horology. Across these objects, devotional, astronomical, musical, or enamelled, Morgan traced a long arc where timekeeping served as a means of measurement and a form of cultural language.

His collecting logic extended from the private to the institutional. Through the 1912 catalogue, he created a bibliographic monument equal in ambition to the objects it described. Through his 1917 donation to the Met, he ensured that the collection would remain intact, accessible, and preserved within a public framework. The watches he assembled continue to instruct in matters of craft and technique, as well as in the broader intersections between mechanical invention, belief, science, and beauty.

Back to top.