When I look at the current landscape of watch culture, I see a tension that defines our time. On one side lies the fascination with the way a watch appears on the wrist, and the endless variations of colour and form that drive demand. On the other lies a culture that is older, slower, and infinitely more complex; the science of horology, the mastery of craft, and the knowledge transmitted across centuries. In recent years, I have felt this latter culture slipping into the background, lost beneath the pageantry of style.

Yet at the same time, I have witnessed a counter-movement taking shape in Switzerland, a series of initiatives that seek to protect, project, and transmit the deeper culture of watchmaking. I see in them a form of resistance, a refusal to let horology dissolve into an empty shell of design. This is the rise of Swiss horological institutions.

The Clockmakers’ Museum in London. Originally displayed at the Guildhall, the collection is now on display at the Science Museum.

The early resistance

It is worth remembering that Switzerland, for all its dominance in production, did not take the first steps in creating enduring institutions around horology; Britain anticipated this need by centuries. In 1631, Charles I granted a royal charter to the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, giving formal civic recognition to the craft. What began as a guild evolved into a guardian of standards, a keeper of apprenticeships, and eventually the custodian of one of the world’s great collections, the Clockmakers’ Museum.

That collection, now housed in the Science Museum in London, preserves masterpieces of English horology and the civic memory of a city where watchmaking once formed a part of daily life. Londoners could walk past the Guildhall and see horology granted the same public stature as that of goldsmiths and merchants.

The Horological Journal of the British Horological Institute. Image – collage

By the nineteenth century, Britain deepened this framework with the founding of the British Horological Institute (BHI) in 1858. This was a moment of industrial acceleration, when precision shaped railways, telegraphy, and navigation, and training required structure and certification. The BHI created that structure. Through examinations, publications, and its museum at Upton Hall, it gave coherence to a dispersed trade.

The BHI’s most enduring contribution, Horological Journal, has appeared monthly since its inception, the oldest continuously published technical journal in the world. To read through its pages is to watch horology travel from lever escapements to quartz, from marine chronometers to wristwatches, from imperial circuits to a global industry.

The Antiquarian Horology journal of the Antiquarian Horological Society. Image – collage

A century later, in the aftermath of the Second World War, Britain added another pillar. In 1953, the Antiquarian Horological Society (AHS) formed as a home for collectors, scholars, and enthusiasts. A different mood informed this creation: horology as cultural history, a field worthy of research and preservation.

The AHS built a forum where museum curators, private collectors, and academics could meet. Its quarterly journal, Antiquarian Horology, opened space for technical studies, archival discoveries, and essays on makers and techniques, circulating insights well beyond specialist workshops. The Society showed that scholarship and collecting could sustain the craft’s memory alongside its practice.

These British institutions reveal a long view shaped by circumstances uniquely their own. By the time the AHS formed in 1953, British watchmaking had already lived through its decline. Swiss competition and American mass production had eroded London’s position as a center of fine timekeeping. The workshops that once clustered around Clerkenwell had largely closed or turned to other trades. In this context, the Society’s founding represented something more poignant than professional organisation. In essence, it was an act of cultural rescue, an effort to preserve the memory of a craft that was slipping away from British shores.

Meanwhile in Switzerland

The Swiss, by contrast, had little need for nostalgia. In 1953, the workshops of the Jura hummed with activity. Families passed techniques across generations, valleys specialised in particular complications, and innovation drove production forward. For them, horology was not merely heritage to be preserved but a living practice to be refined. The Swiss were absorbed in the making of timekeeping instruments, their relationship with the craft rooted in the present, active, evolving, and centered on the workshop rather than the archive.

It would take the existential shock of the quartz crisis in the 1970s and 1980s to fundamentally alter this perspective. Suddenly, mechanical watchmaking appeared fragile, its future uncertain. Only then did Swiss makers begin to see their traditions as precious cultural heritage rather than simply industrial practice.

Civic recognition, professional structure, and scholarly attention had supported the culture of horology in Britain while others focused on production alone. The Swiss institutional awakening, when it came, would be informed by this earlier British model but shaped by their own distinct circumstances and needs.

The Musée International de la Horlogerie. Image – MIH

A turning point

In Switzerland, the gap began to close in the 1970s, when La Chaux-de-Fonds inaugurated the Musée International d’Horlogerie (MIH). Ambition shaped the MIH from the start: a civic project to preserve the world’s horological heritage, with a collection that now exceeds ten thousand objects. Its architecture, partly subterranean and echoing the layered geology of the Jura, conveys a sense of horology as a deep cultural stratum. The museum became a reference point for the public, scholars, and professionals alike.

In 1993 it created the Gaïa Prize, honouring the achievements of makers, researchers, and entrepreneurs. During years of upheaval, the MIH held a steady course and affirmed horology as culture with a past, a present, and a future.

The 1970s witnessed parallel developments across the Atlantic, where the United States approached horological preservation through multiple complementary channels. The most visible was the grassroots movement: in 1977, the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors (NAWCC) established the National Watch & Clock Museum in Columbia, Pennsylvania. Unlike the guild-based British model or the emerging Swiss institutional framework, NAWCC represented democratised enthusiasm, thousands of individual collectors pooling resources and knowledge to create a repository of American timekeeping history.

The Library of the Horological Society of New York. Image – HSNY

But America also developed institutional frameworks that paralleled British models. The Horological Society of New York (HSNY), founded in 1866 and thus contemporary with the BHI, had weathered the industry’s various upheavals and by the 1970s was positioning itself as a serious research institution. Its crown jewel became the Maersk Library, housed within the HSNY’s headquarters and containing one of the world’s finest collections of horological literature, technical manuals, and archival materials.

Simultaneously, the Smithsonian Institution significantly expanded its horological collections during this period, with the National Museum of American History becoming a major repository of timekeeping artifacts. This federal involvement added another layer to American preservation efforts, but it was a private initiative that captured the decade’s most ambitious vision for horological display.

In 1971, predating even the NAWCC museum’s founding, industrialist Seth Atwood opened the Time Museum in Rockford, Illinois, housing what many considered the world’s finest collection of timepieces. For over two decades, the Time Museum set the global standard for horological exhibition, with masterpieces ranging from ancient sundials to modern complications. Its closure in 1999 and the subsequent dispersal of the collection through auctions reminded the horological community of the fragility of even the most magnificent private initiatives, underscoring the importance of sustainable institutional structures.

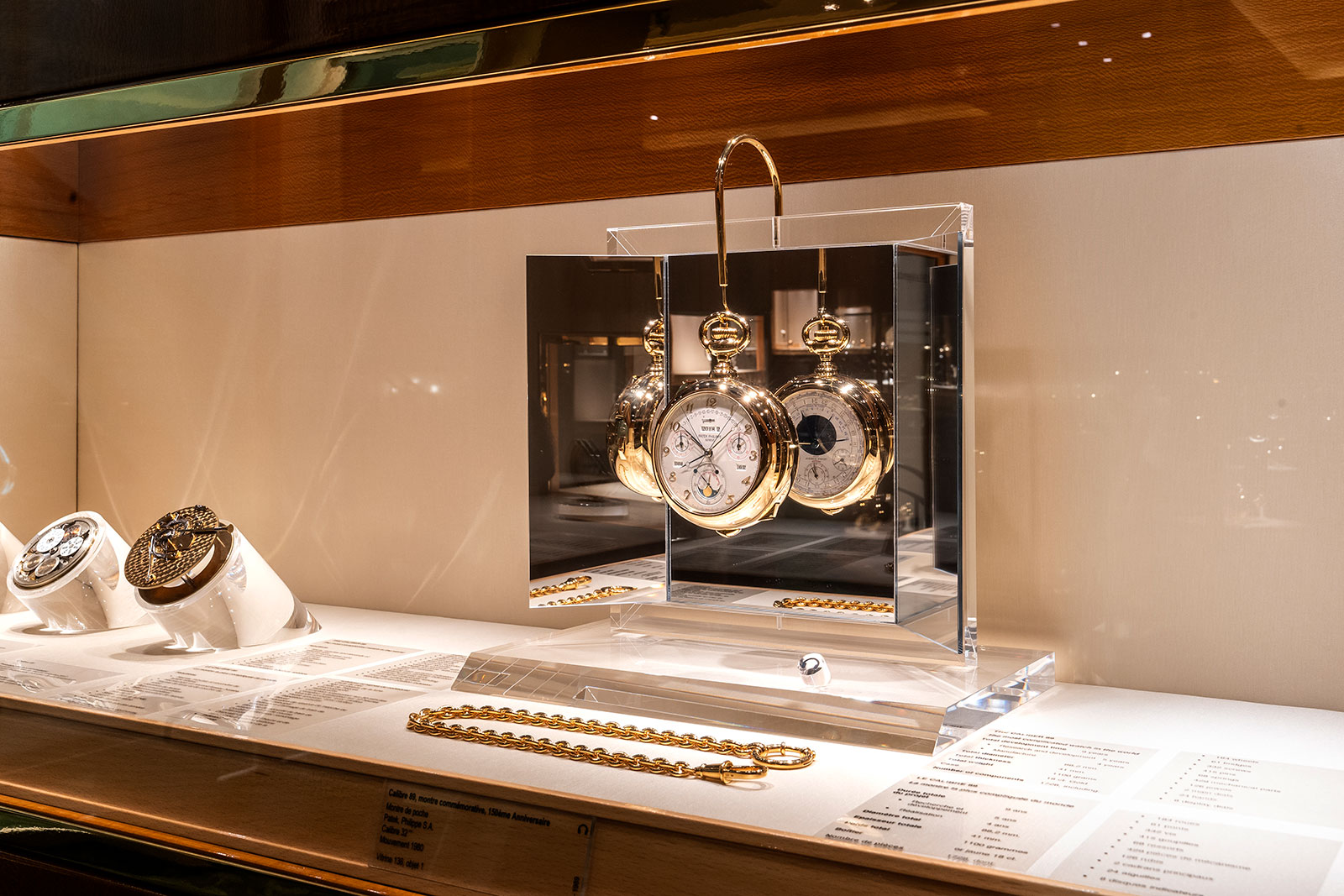

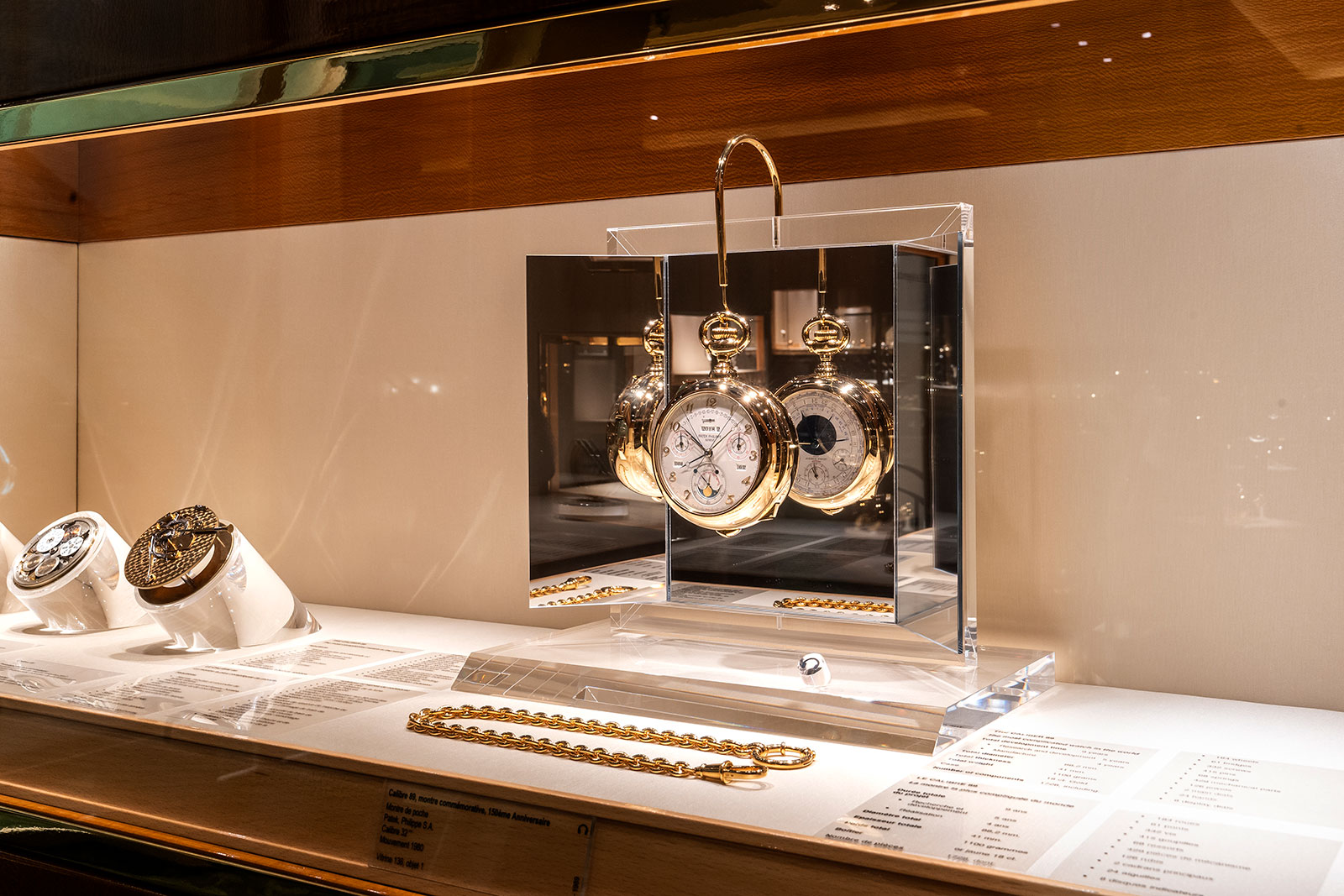

The Patek Philippe Museum – image SJX

Not long after the Time Museum closed its doors for the last time, Geneva welcomed the Patek Philippe Museum. Philippe Stern, then president of the firm, had spent years assembling a collection that braided the history of the brand with an encyclopaedic survey of horology.

Thanks in part to the keen eye of Alan Banbery, the museum now houses more than two thousand watches, automata, and enamels, alongside an extensive library. This private initiative, dedicated to public access and scholarship, set a standard for cultural stewardship within a brand setting and presented the craft in its full breadth.

The institutional developments in Britain and America provided models and lessons, but in Switzerland, the landscape remained more limited. For many years, the MIH and the Patek Philippe Museum formed the centre of gravity. Over the past decade, however, a broader movement has taken shape. Digital and physical projects now appear in quick succession, each with a distinct role, and together they form an ecosystem Switzerland long awaited.

The Europa Star Archives. Image – collage

Hertitage, digitised

The transformation of Europa Star into a living archive marked an early signal. Founded in 1927 by Hugo Buchser, the magazine chronicled the fortunes of the watch industry for almost a century. Under the leadership of Serge Maillard, a large-scale digitisation began; by 2019 tens of thousands of pages had already moved online.

The archive now spans more than sixty thousand digitised pages, searchable by keyword, date, and theme. Researchers and enthusiasts can follow the industry’s voice across time, its response to the quartz era, its approach to the revival of mechanical watchmaking, and its language of luxury through the 1990s. Europa Star’s archive moves beyond nostalgia toward context, granting access to the record on which authentic memory rests.

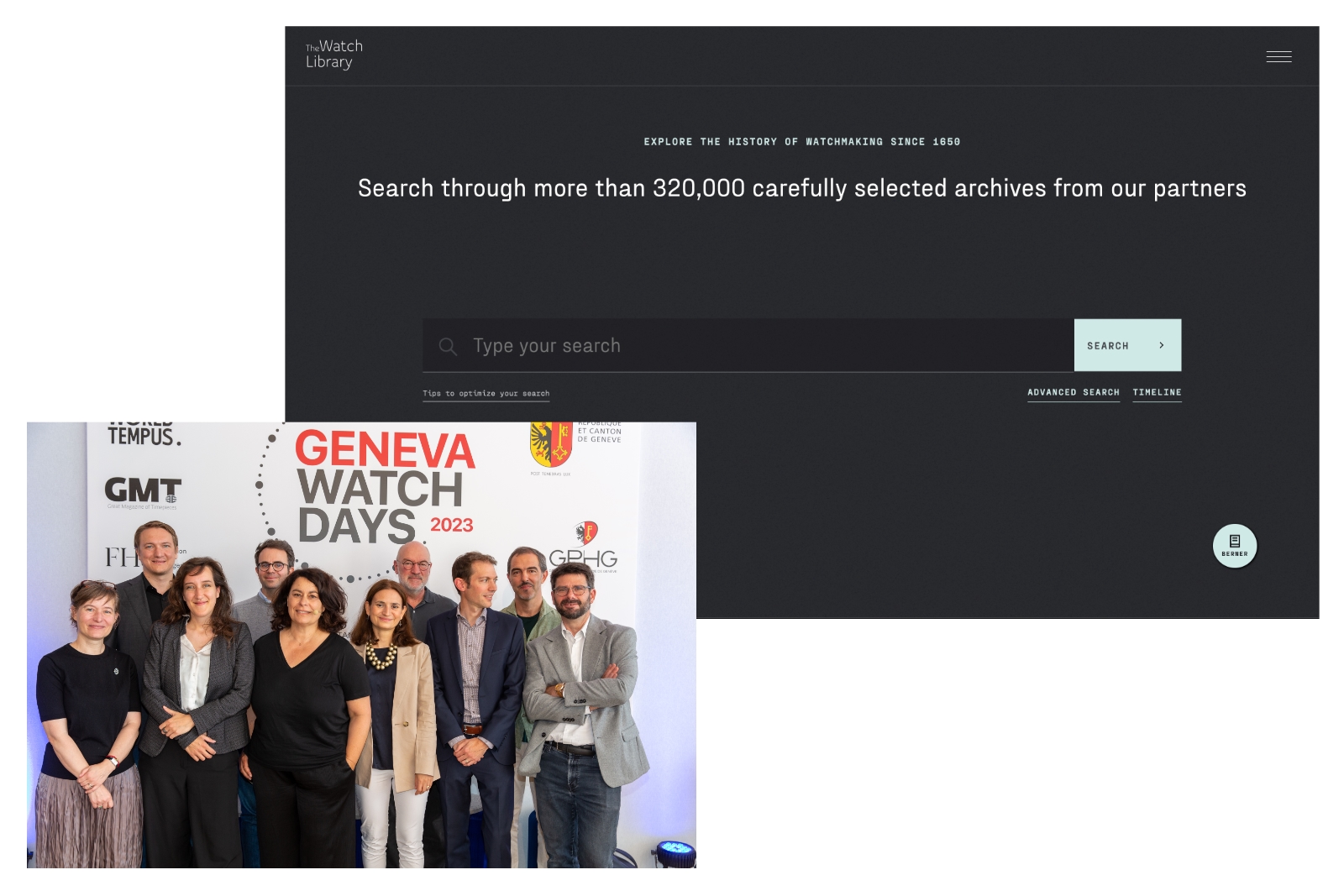

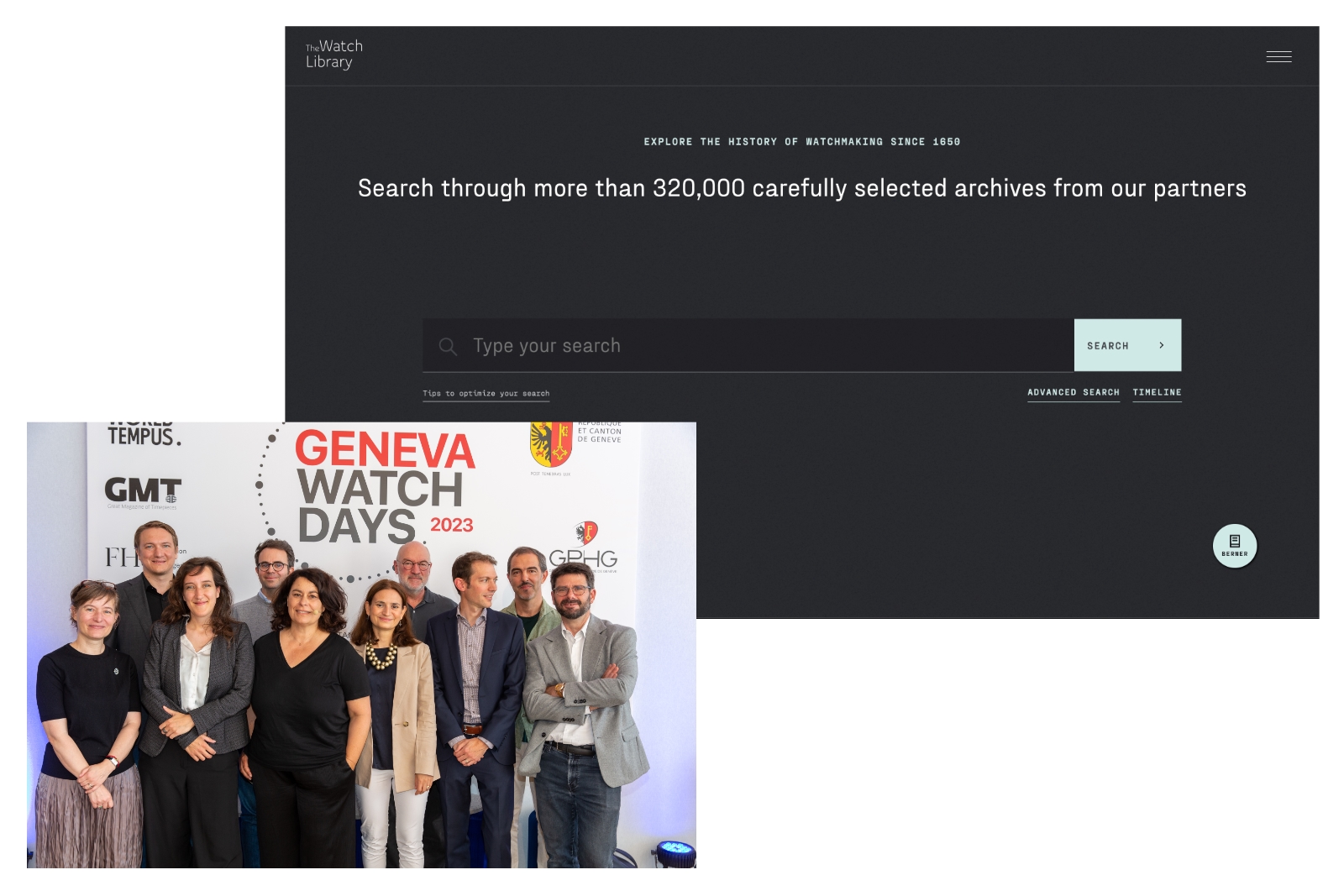

The Library Foundation. Image – collage

Two years later, the Watch Library Foundation took shape. Established in 2021 and recognised as a public-utility foundation in 2022, it brings together archives from museums, brands, libraries, private collections, suppliers, and media. Its board connects publishing, curatorship, and academia: Serge Maillard of Europa Star, Nicholas Manousos of the HSNY, Régis Huguenin-Dumittan of the MIH, and Ellan Spero of MIT, among others. Public authorities, notably the Canton of Geneva, and private patrons, including Audemars Piguet, TAG Heuer, and Richard Mille, support the effort.

During Geneva Watch Days 2023 the platform already offered more than three hundred thousand digitised pages, from seventeenth-century treatises to twentieth-century trade catalogues. Neutral governance, broad partnerships, and technical scale give the Library a singular role: heritage as shared infrastructure, searchable and usable across borders.

The Horopedia Founders. Image – Horopedia

Almost in parallel, a complementary effort gathered momentum under Marc André Deschoux, founder of The Watches TV. In 2022, he launched Horopedia, a free, multilingual, video-based encyclopaedia of watchmaking, and in 2023 it became a foundation of public interest in Geneva. Its council includes Philippe Dufour as president, with Dr. Helmut Crott and André Colard.

Horopedia documents the world of horology through its processes: materials, tools, machines, finishing techniques, mechanical principles, and institutions. The platform already offers more than a hundred films and nearly a thousand pages of definitions and historical notes. Funded by donations, it provides visual pedagogy with expertise at its core, a curriculum for the digital age, open to students, apprentices, and curious viewers everywhere.

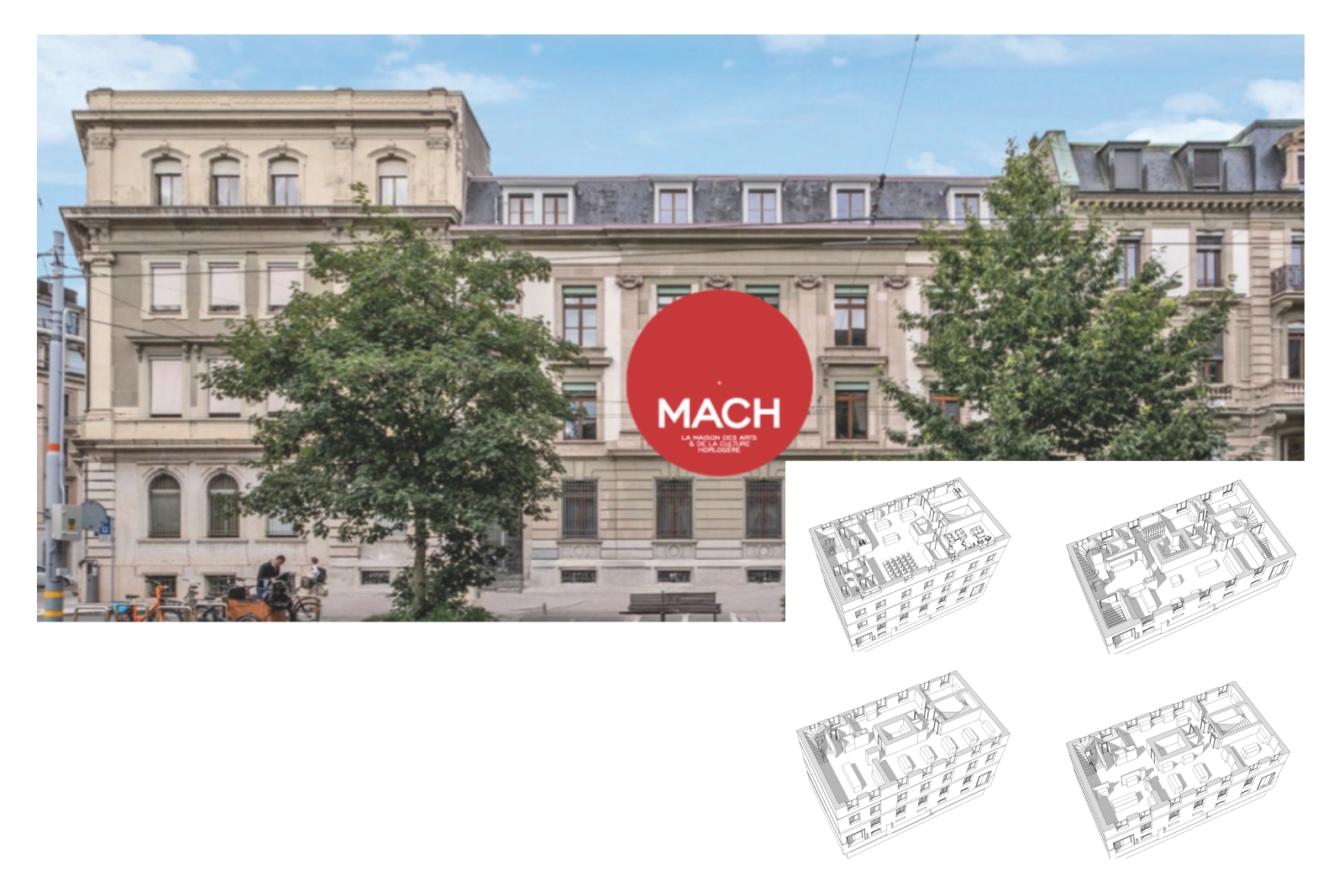

The Maison des Arts et de la Culture Horlogère. Image – collage

From that digital base emerged a physical house. In 2023, the Maison des Arts et de la Culture Horlogère (MACH) was announced for Geneva’s Quartier des Banques, with the opening planned for 2026. MACH will welcome visitors to four public floors with thematic displays on métiers and principles of watchmaking; a historical journey through five centuries with live workspaces and an auditorium for events and teaching.

The founding circle includes familiar names like Philippe Dufour, Helmut Crott, André Colard, and Marc André Deschoux, and draws additional support from figures such as François-Paul Journe and Maximilian Büsser. The aim is simple and ambitious: a civic home where watchmaking stands in the realm of culture, and where young visitors can discover pathways into training and vocation.

The 10:10 Initiative Founders. Image – 10:10

Celebrating World Watch Day

Another initiative, compact in structure and wide in spirit, is the World Watch Day Association. Established in 2023, it proposes October 10, echoing the familiar 10:10 time display, as a global day of horology. Founders such as Jean-Daniel Dubois anchor the idea within a broader cultural recognition, in line with UNESCO’s 2020 inscription of Franco-Swiss mechanical watchmaking and art mechanics as intangible heritage. A single day on the calendar creates a ritual, a moment when watchmakers, collectors, and enthusiasts gather attention and celebrate the craft together.

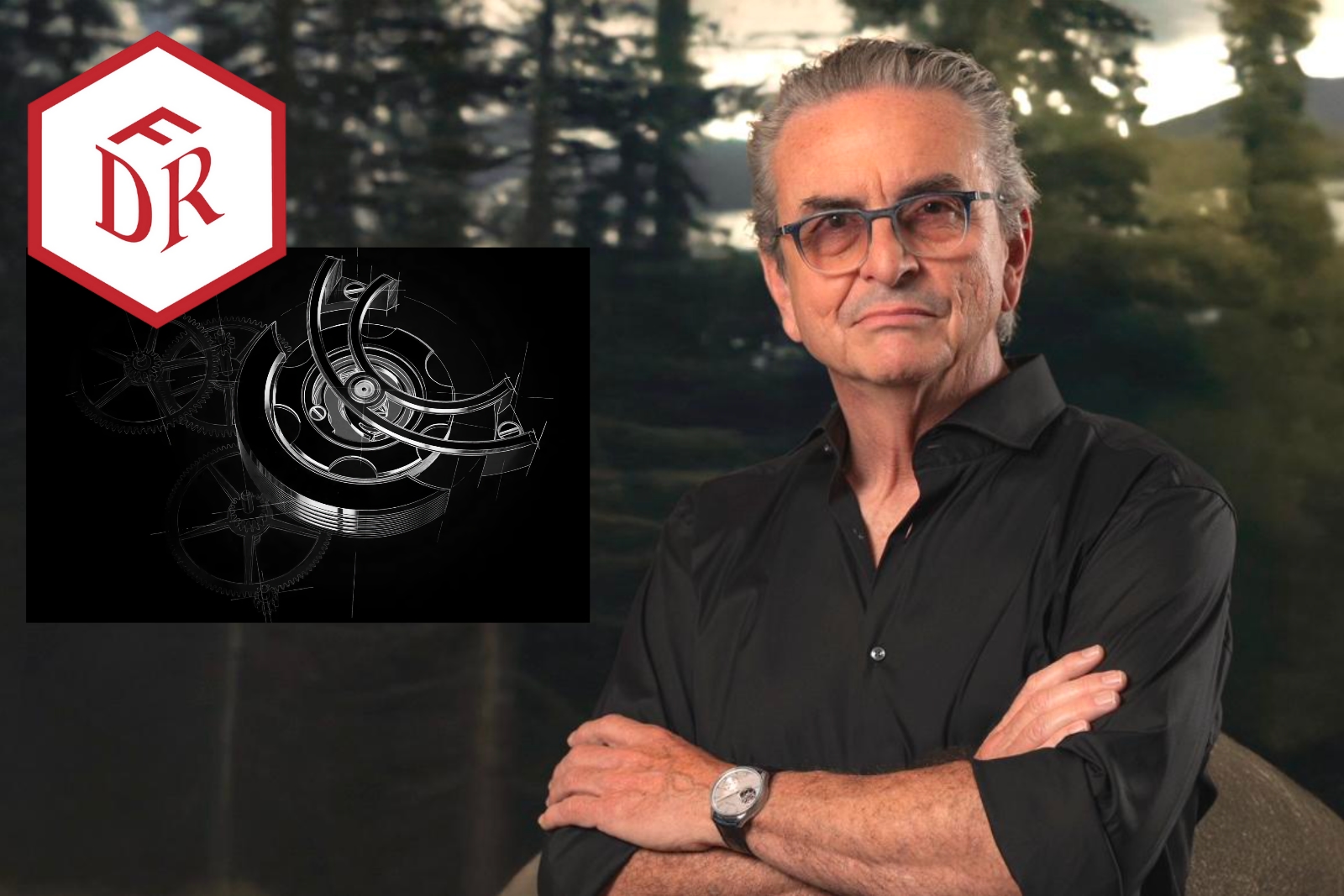

The Fondation Dominique Renaud. Image – collage

Another contribution, anchored in the legacy of an individual maker, is the Fondation Dominique Renaud, created in 2025 in Neuchâtel. Its mission is to safeguard and transmit the creative work of Dominique Renaud, whose forty-year career shaped some of the most advanced complications of recent decades.

The foundation gathers his drawings, prototypes, models, and watches, building a corpus that will serve exhibitions, research, and education. Its board includes Jean-Frédéric Jauslin alongside Dominique Renaud himself, François Cornu, Olivia Dhordain, and Benoît Dubuis. This project extends the institutional landscape by focusing on one master’s ideas, preserving them for scholars and inspiring new generations. It shows how personal innovation can become a shared cultural resource once it is curated and transmitted with intent.

Around these flagship projects, other institutions continue to enrich the field. The Beyer Museum in Zürich preserves one of the world’s oldest private collections, open to the public since 1971. The Château des Monts in Le Locle and the Espace Horloger in the Vallée de Joux illuminate regional traditions and métiers.

The Musée Atelier Audemars Piguet, opened in 2020, presents a brand’s heritage in an architectural setting designed for public discovery. The Omega Museum in Biel, a pioneering mono-brand museum that opened in 1984, and the Time Aeon Foundation, dedicated to hand methods through collaborative projects, broaden the constellation.

For his part, François-Paul Journe is set to open a new museum in Geneva in the coming years, which will display the recently acquired Breguet Sympathique No. 1. The emergence of these private institutions illustrates a country assembling a cultural framework that supports scholarship, teaching, restoration, and public engagement.

The Espace Horloger. Image – Espace Horloger

Concluding thoughts

What stands out in this recent wave is its character. Collaboration, digital reach, and independent governance shape these undertakings. Individuals like Serge Maillard, Nicholas Manousos, Régis Huguenin-Dumittan, Marc André Deschoux, Philippe Dufour, François-Paul Journe, Dominique Renaud, and Maximilian Büsser place conviction and time behind them. Their names matter because institutions gain life through people who understand what is at stake and act accordingly.

The British model showed long ago that horology thrives when guild, institute, and society work in concert. Switzerland now assembles its own version for the present era, open, digital, international, and collaborative. The MIH and the Patek Philippe Museum set early points of reference; the newcomers enrich the field with distinct perspectives. Their significance lies in what they seek to preserve – the history, science, of culture of watchmaking. When horology stands on that foundation, it continues to matter, on the wrist and in the record of human ingenuity.

I consider these projects acts of resistance because they return substance to the conversation. A watch carries invention, skill, and history. These initiatives create spaces, physical and digital, where knowledge finds form and where transmission becomes a shared task. I welcome these initiatives for what they safeguard and for what they set in motion, the outlines of a future where horology is remembered, taught, and renewed.

Back to top.