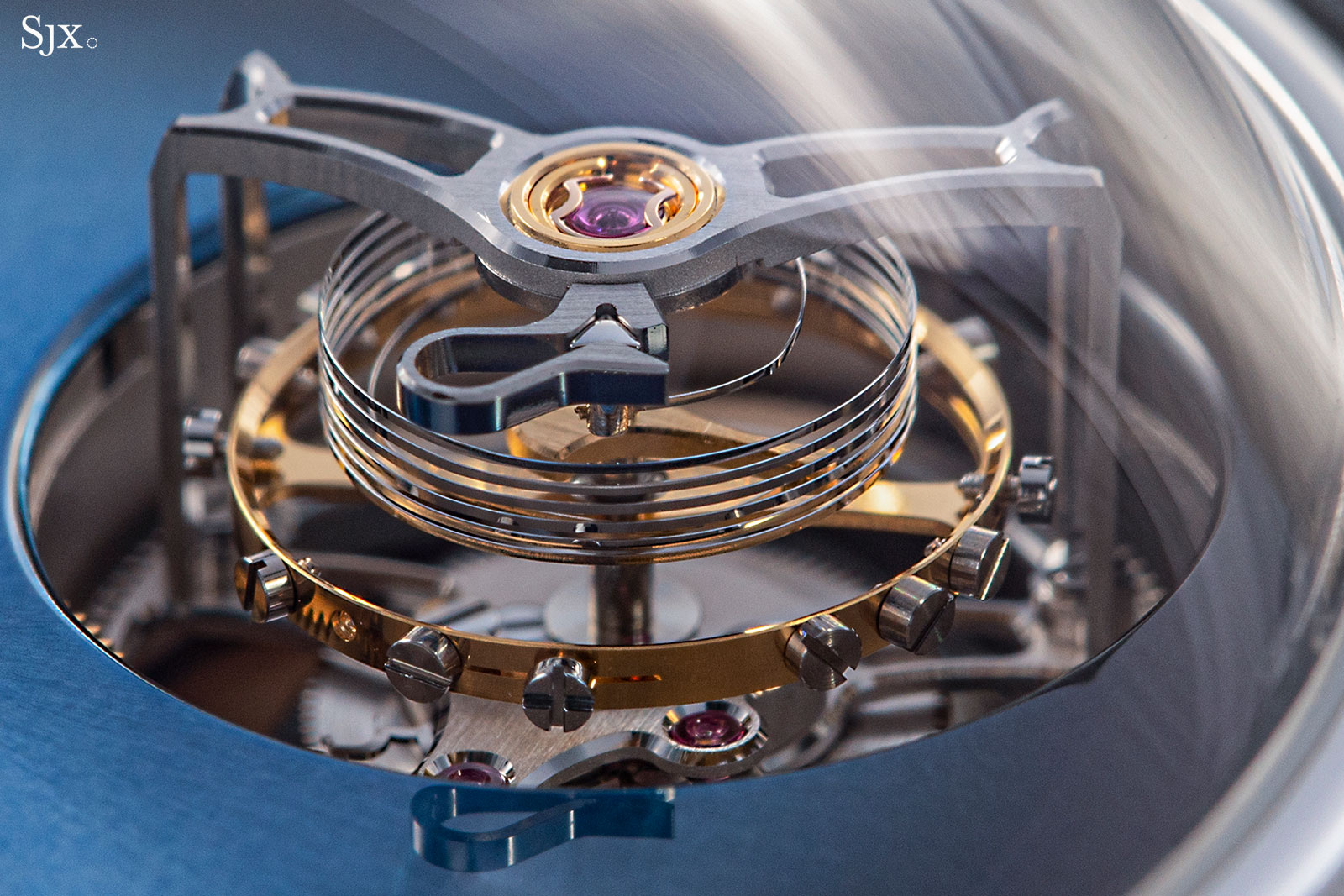

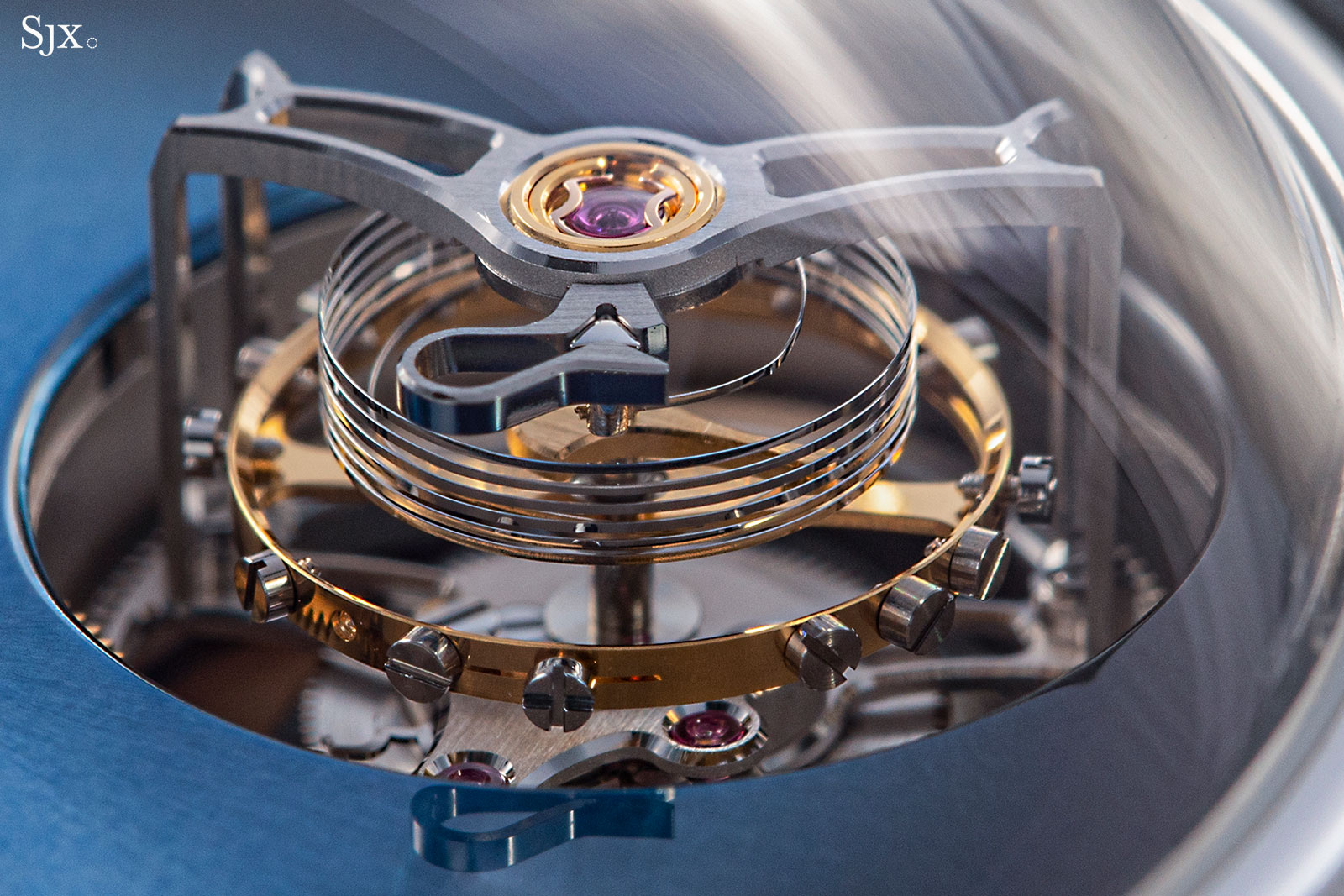

Twenty twenty-five marks the 350th anniversary of the hairspring – it’s hard to believe the spiral ticking away in tens of millions of mechanical watches is already over three centuries old. The hairspring’s history is marked by revelations, disputes, and technical advancements, driven forward by creative horological minds, making the story of the hairspring a fascinating one.

But behind all of that lies the question: who invented the hairspring? There are two familiar contenders for the title and it’ll take a deep dive into history to figure out who deserves credit.

The motivation

Prior to the invention of the hairspring, most timekeepers were clocks. Watches existed, but were essentially miniature clocks that still relied on some sort of gravity pendulum, making such early watches wildly inaccurate. So the hairspring was born of necessity, the need to transform clunky, stationary clocks into relatively precise portable timekeepers.

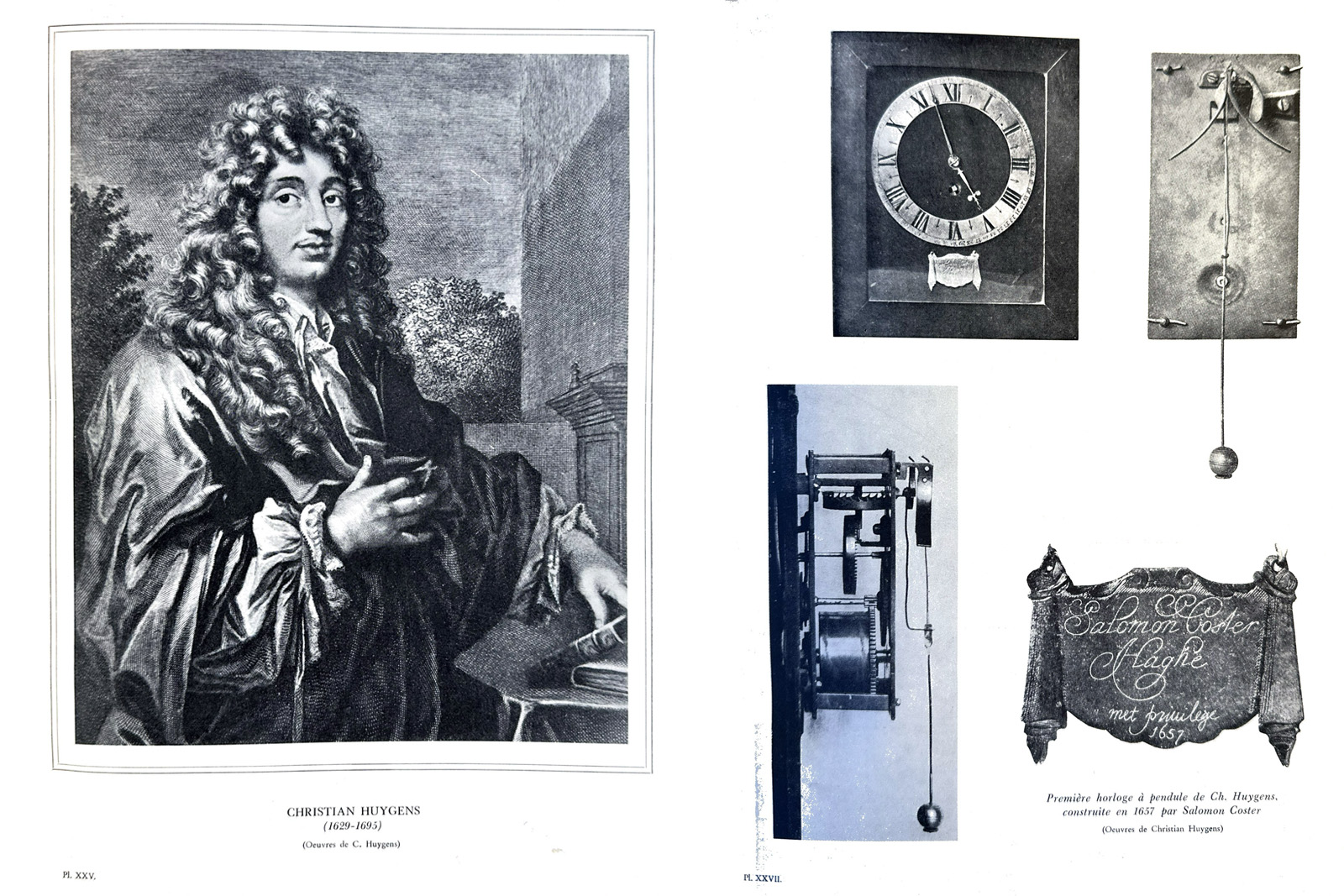

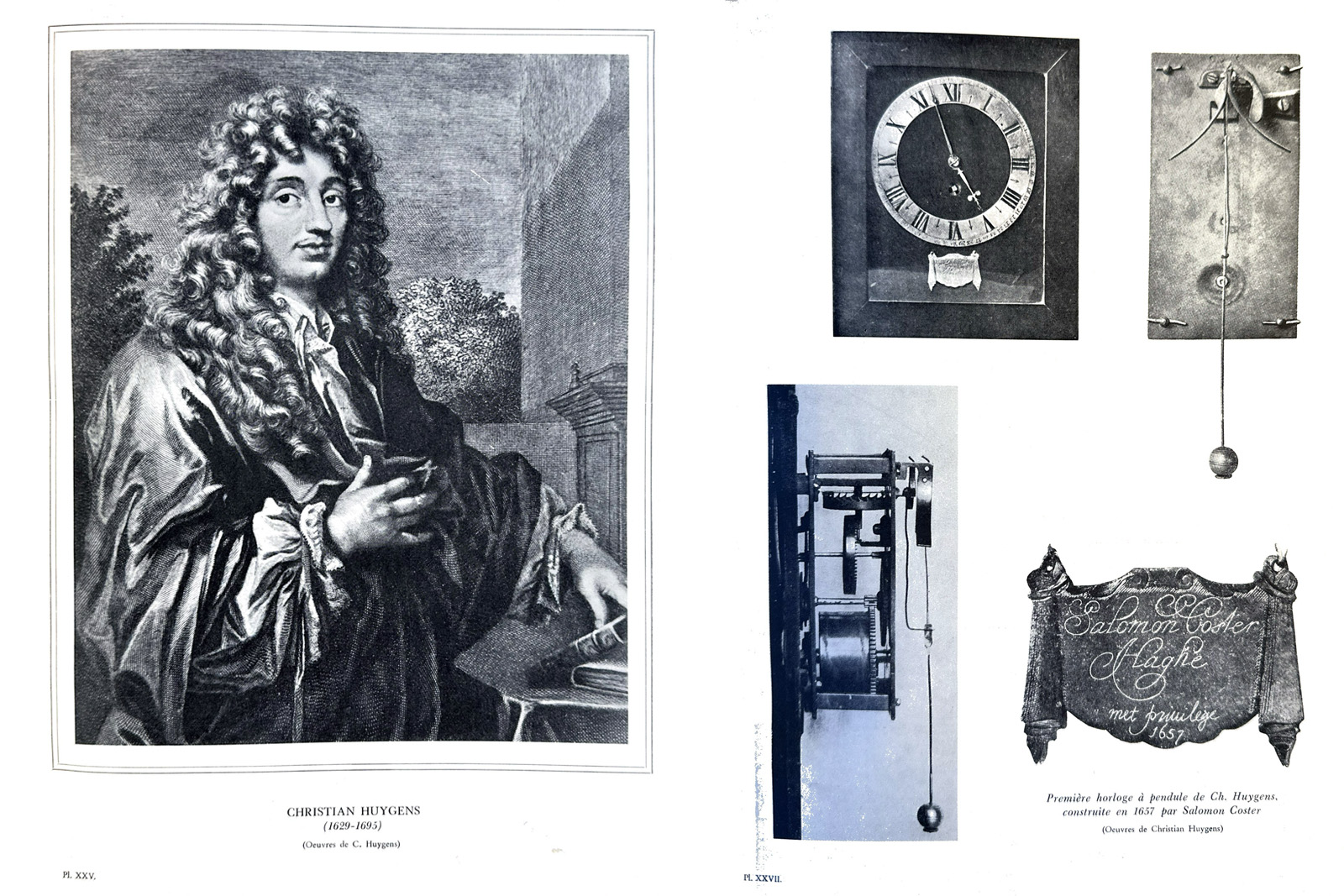

By the mid 17th century, Dutch mathematician and physicist Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695) had already demonstrated a swinging pendulum could indeed serve as a reliable base unit of time measurement for a mechanical timekeeper. He designed his own cycloidal pendulum clocks equipped with oscillating bobs that were only dependent on gravitational acceleration and the cord’s length, making them true isochronous timekeepers. The first such clock was built in 1657 with the help of clockmaker Salomon Coster.

“Isochronous” refers to an oscillator whose vibration period is absolutely independent of amplitude, temperature, friction and other external disrupting factors. Horologists, however, use the term to describe an oscillator which has the same period of swing regardless of its amplitude. True isochronous pendulums were arguably invented by Huygens, who attached a weight to the end of a flexible cord that would be limited by a pair of cycloidal cheeks during its swing, dynamically shortening it at large amplitudes (illustrated below right).

Plates XXV and XXVII from L. Defossez

In time clockmakers adopted simpler, fully rigid pendulums that were meant to oscillate at small amplitudes (a few degrees at most) and which would, for all practical reasons, behave isochronously.

Before Huygens introduced the pendulum as a rigorous timekeeper, clockmakers of the era used rotating inertial bodies (much like balance wheels) that would somewhat regulate the discharge speed of a going train through a verge escapement. The great flaw of this system was the fact that the inertial body had no swing period of its own and the clock’s running would depend heavily on the power supplied to the escapement. Through his work with pendulums, Huygens practically started the era of precision timekeepers.

While precision timekeeping had become a reality, these sophisticated pendulums were designed to be kept stationary, at constant temperatures and in somewhat protected environments. The need for portable timekeepers was starting to become more and more pressing, especially for seafarers. This was tied to the quest for the precise determination of longitude at sea, another challenge that was later solved by English clockmaker John Harrison with his marine chronometer.

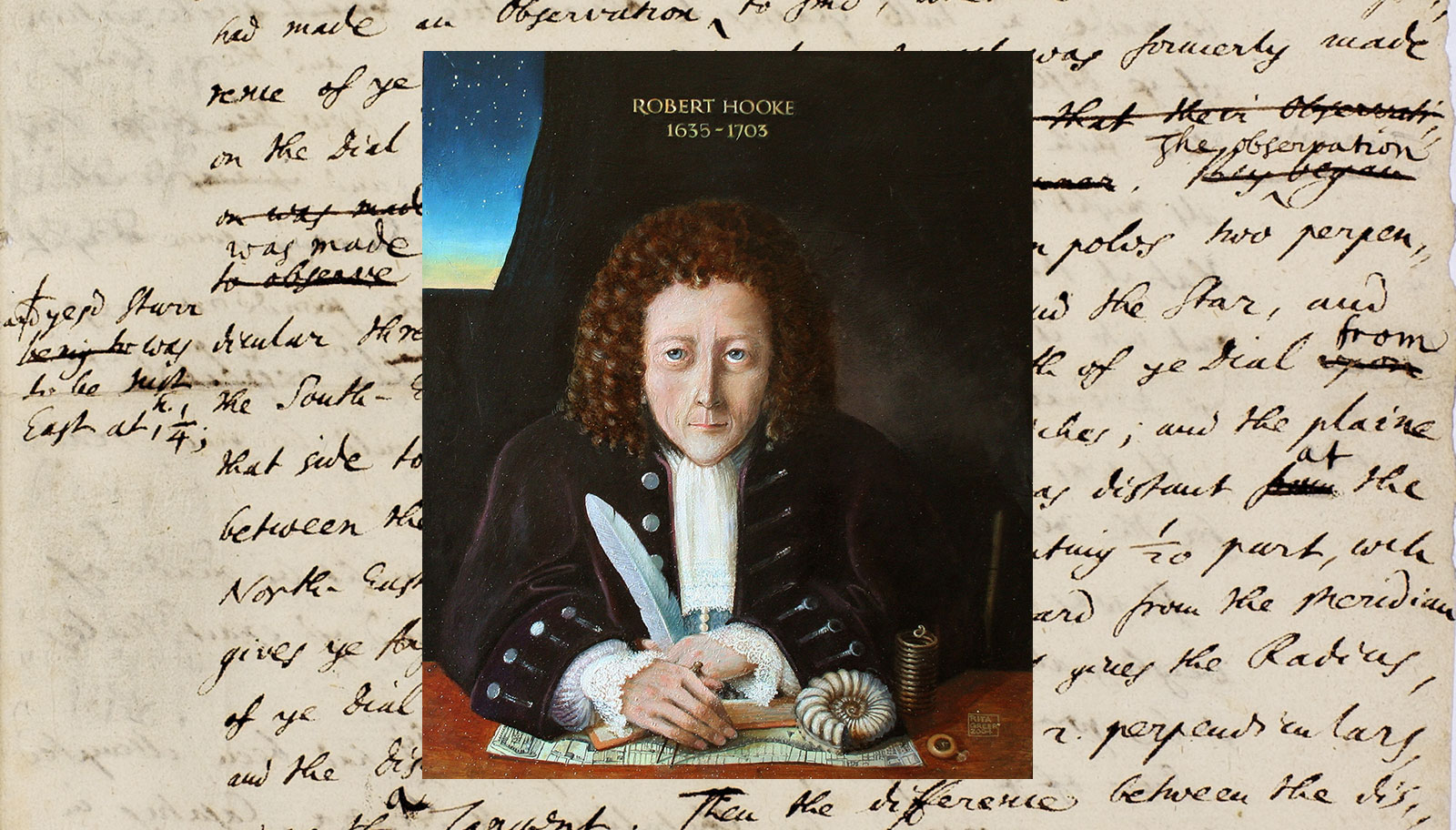

Robert Hooke

In order to break free of the dependance on gravity, a portable oscillator needed to rely on another force that would make a displaced body vibrate harmoniously around an equilibrium position at equal intervals. This is where the English scientist Robert Hooke (1635-1703) first makes his entrance in this field, particularly with his famous law regarding spring behaviour: Hooke’s law.

Hooke was a very influential figure of his era, who preoccupied himself with all kinds of branches of science. While no one can deny his extensive and diverse work, he was notorious for not completing what he started, be it physics concepts or half-perfected inventions.

Robert Hooke portrait by Rita Greer.

As Rupert T. Gould puts it in his seminal work The Marine Chronometer, its history and development:

“It must be admitted, however, that [Hooke’s] attention was never steadily directed for any length of time to one subject, and that he seems to have considered that any hints he threw out as to the nature of his various incomplete inventions or calculations must secure to him all the credit of their actual completion in practical form.”

Gould also notes “[Hooke] was jealous, vain, and quarrelsome, and it will readily be understood that his fellow scientific workers must have regarded him with very mixed feelings,” summing up Hooke’s character and working method.

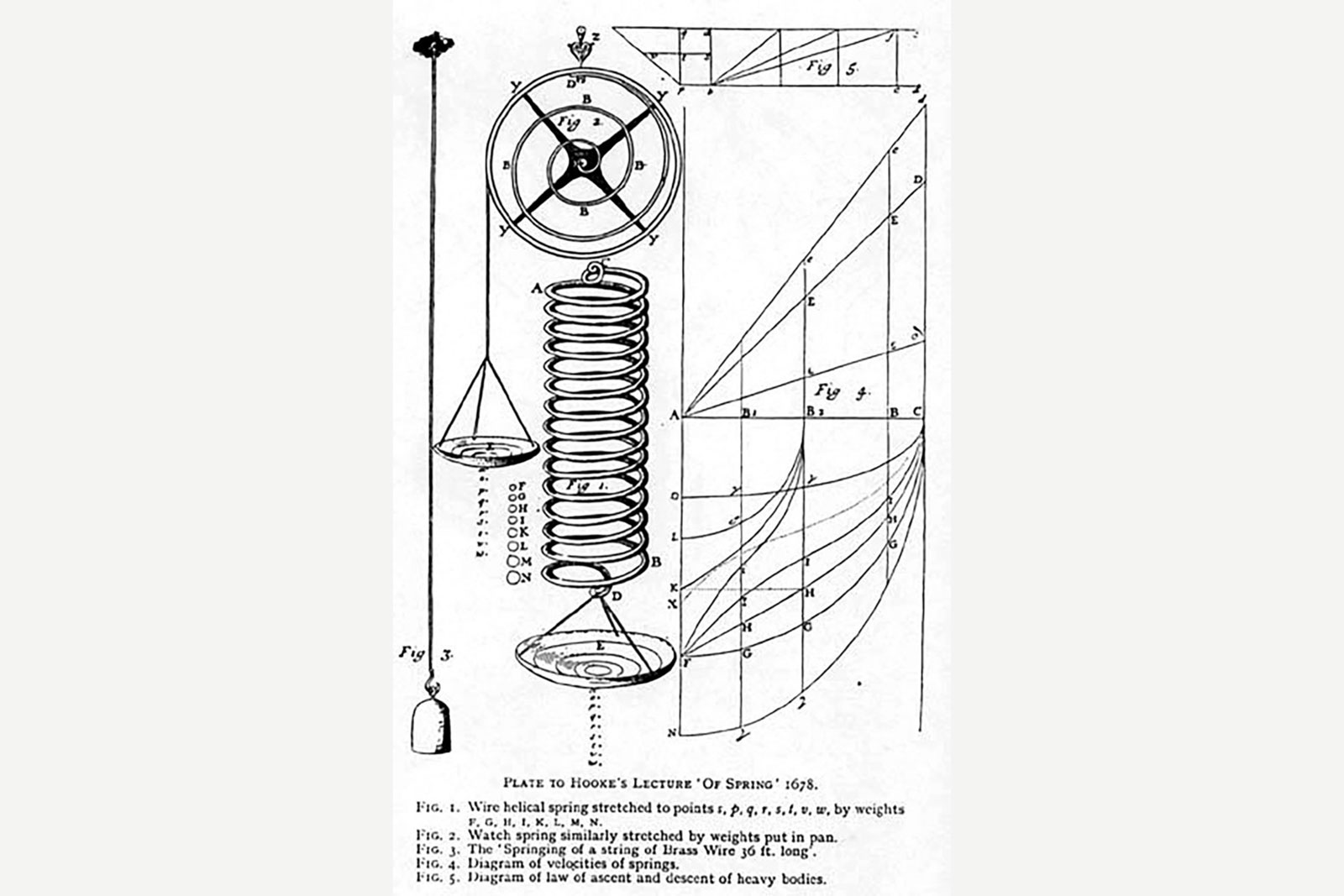

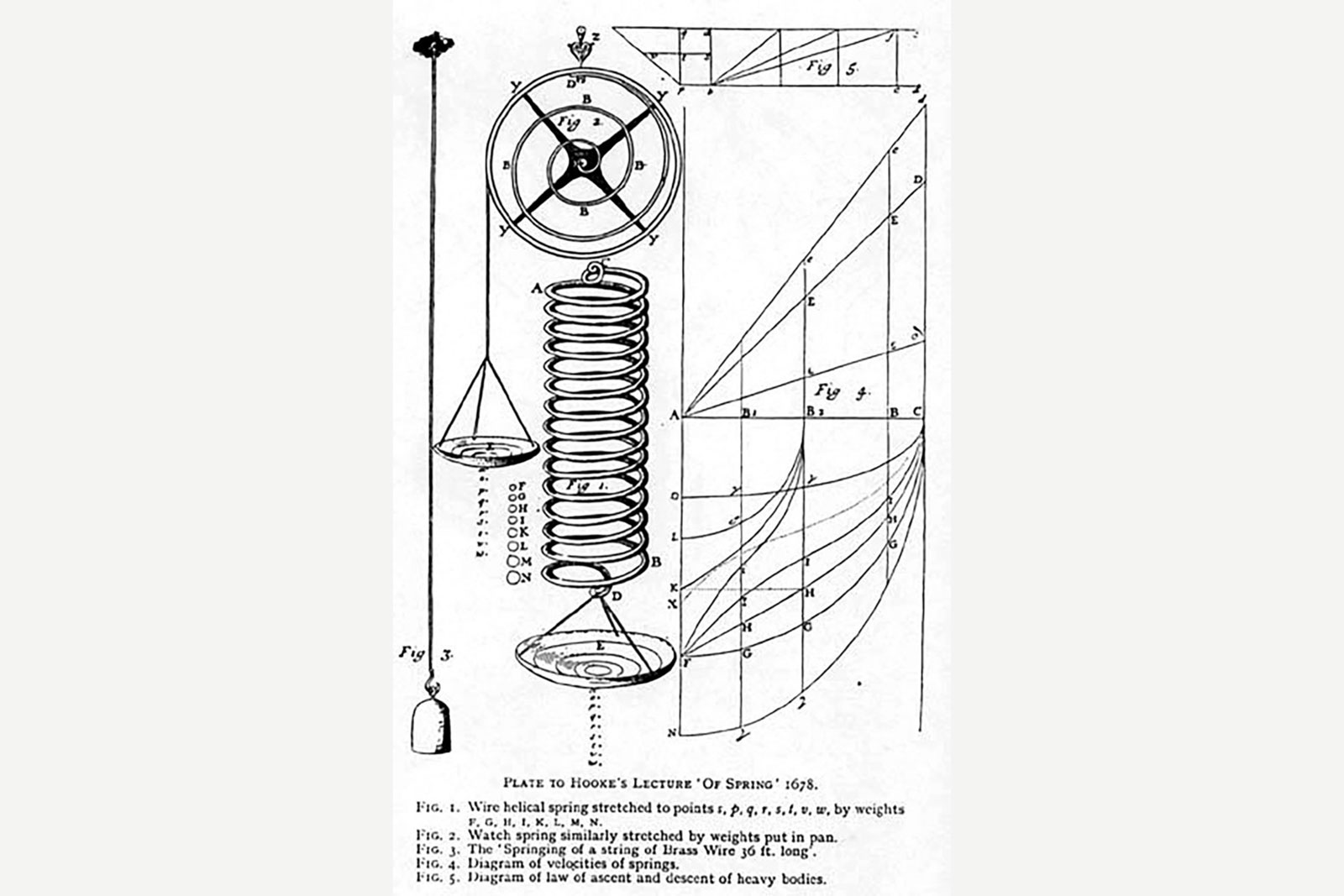

Hooke’s law states the restoring force exerted by a spring is proportional to how much said spring is displaced from its equilibrium point. This seemingly simple principle was enunciated by Robert Hooke in 1678 by way of anagram (as it was common then for protecting scientific communications). Decoded, the Latin anagram reads “Ut tension, sic vis”. Translated, it reads “As the tension is, so is the force”.

While the law was only thoroughly enunciated in 1678, Hooke claims he was well aware of it as early as 1660 and that he spent a great deal of time studying springs and their various mechanical applications. Some of those experiments would relate to the mechanical clock.

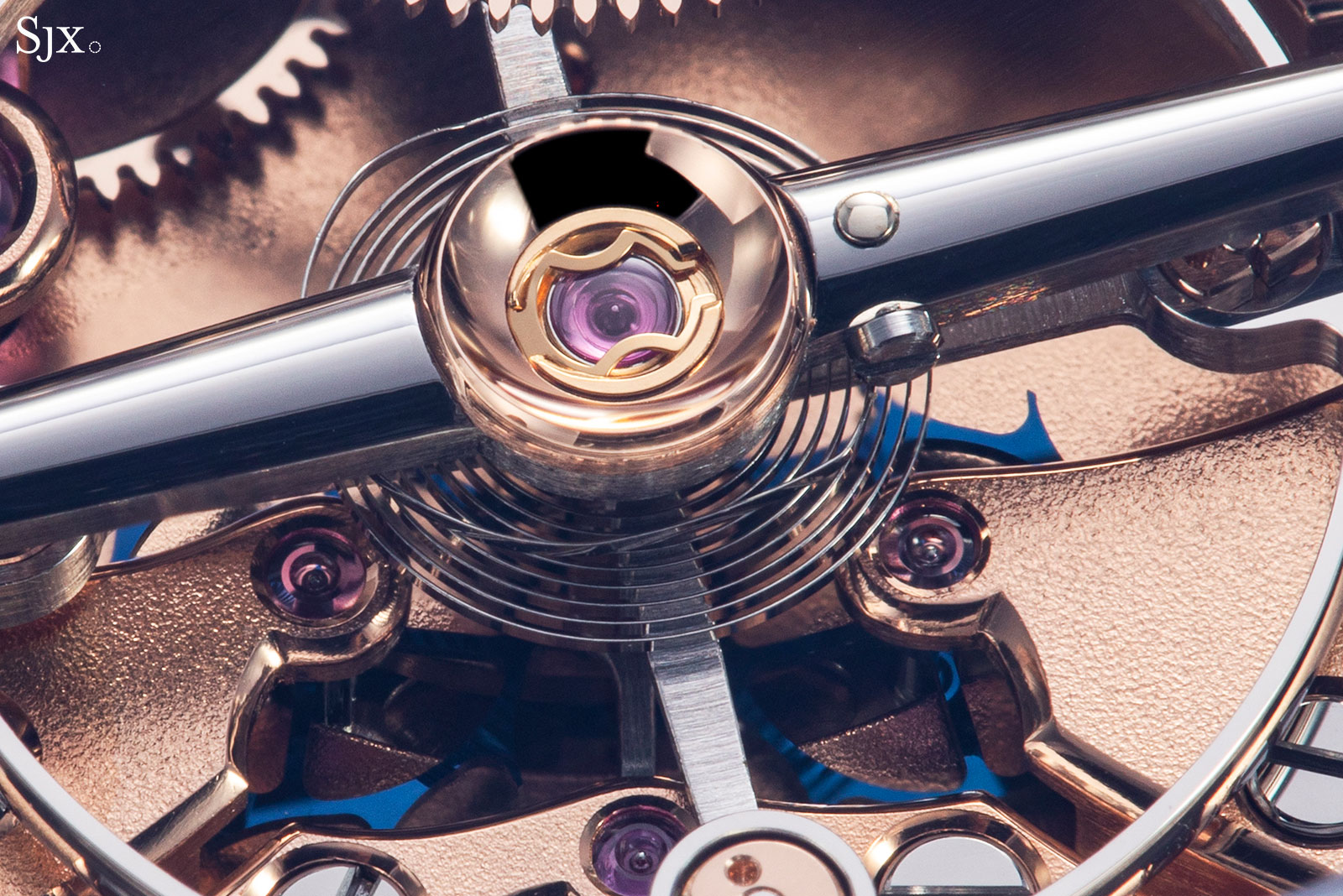

The first hairspring

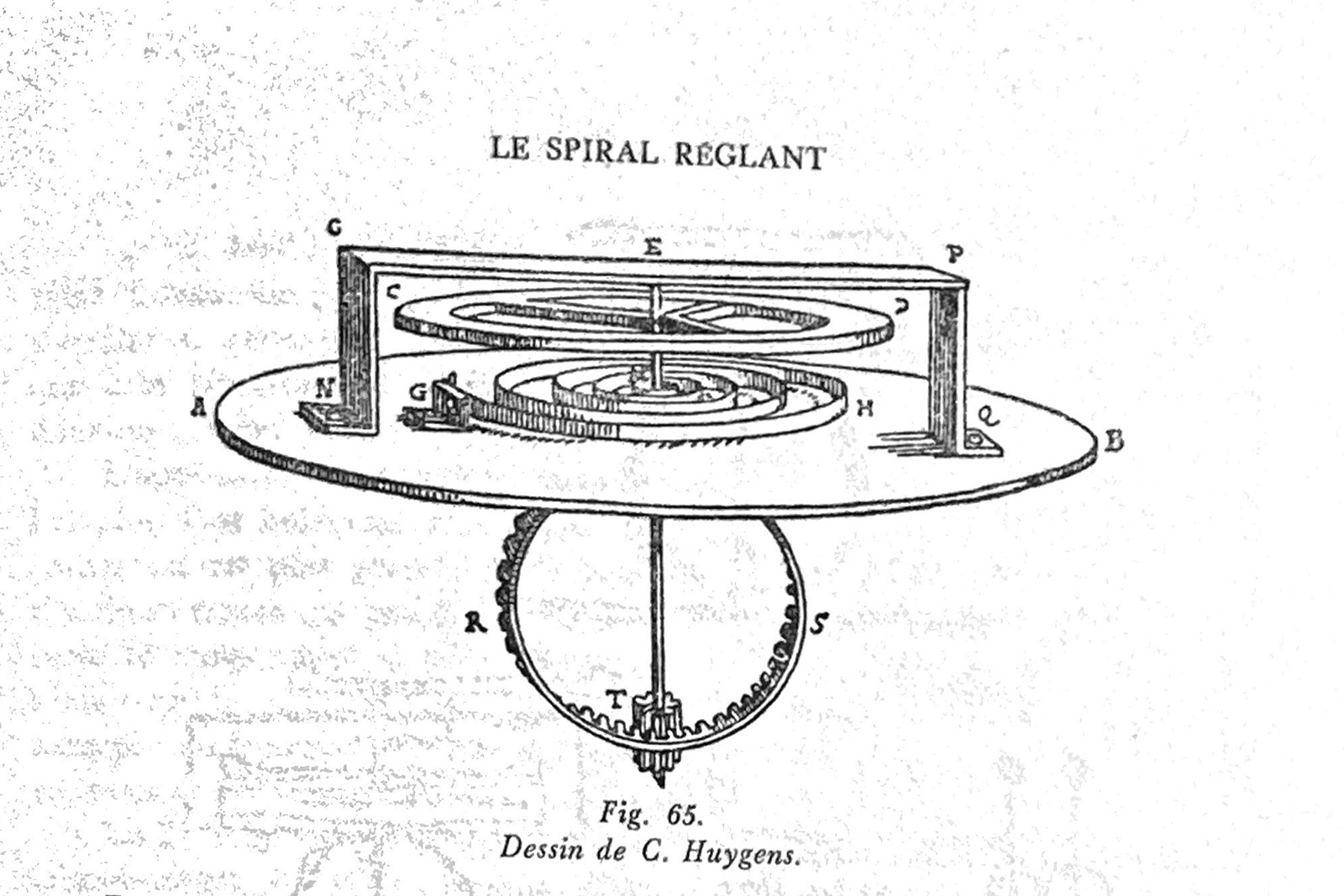

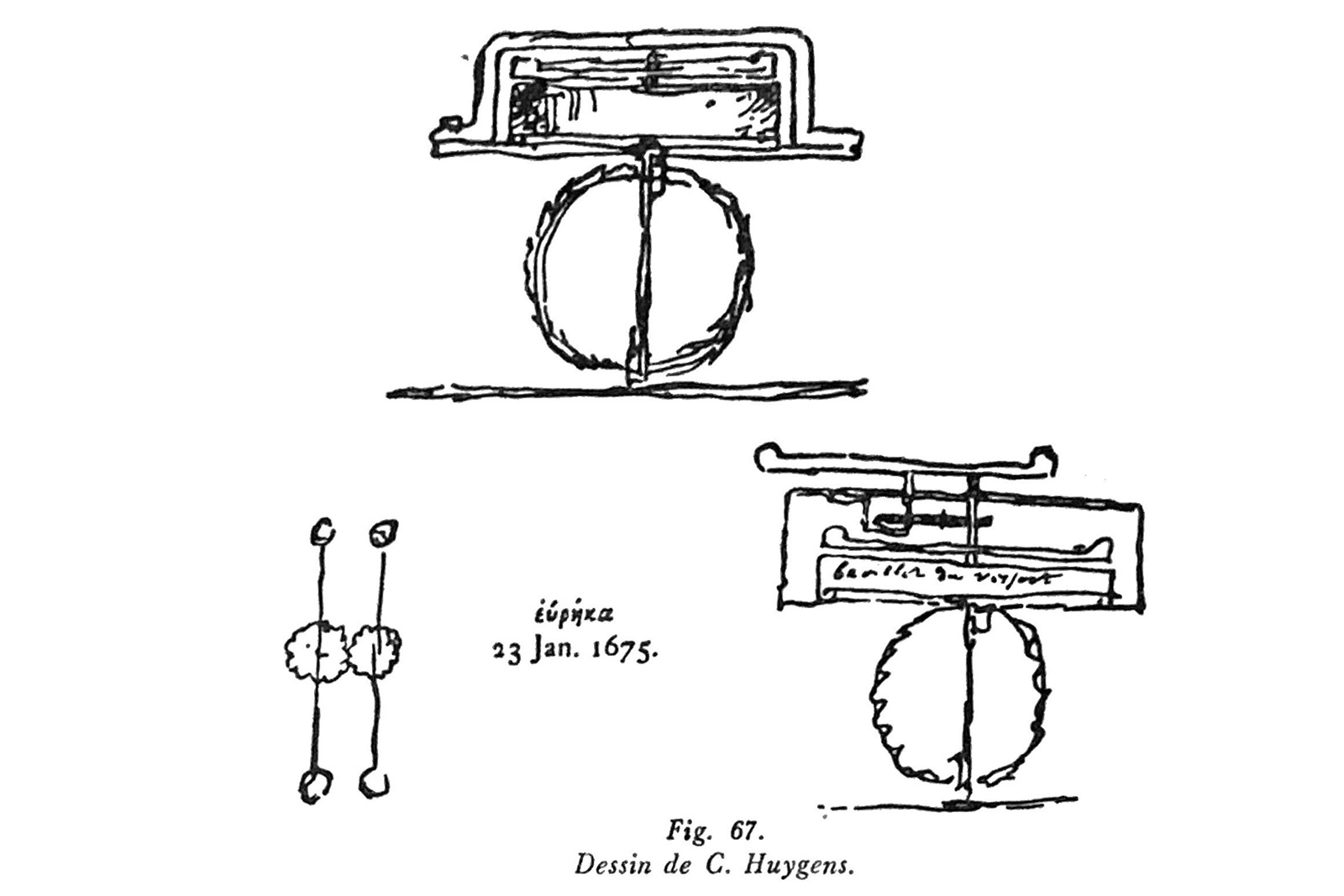

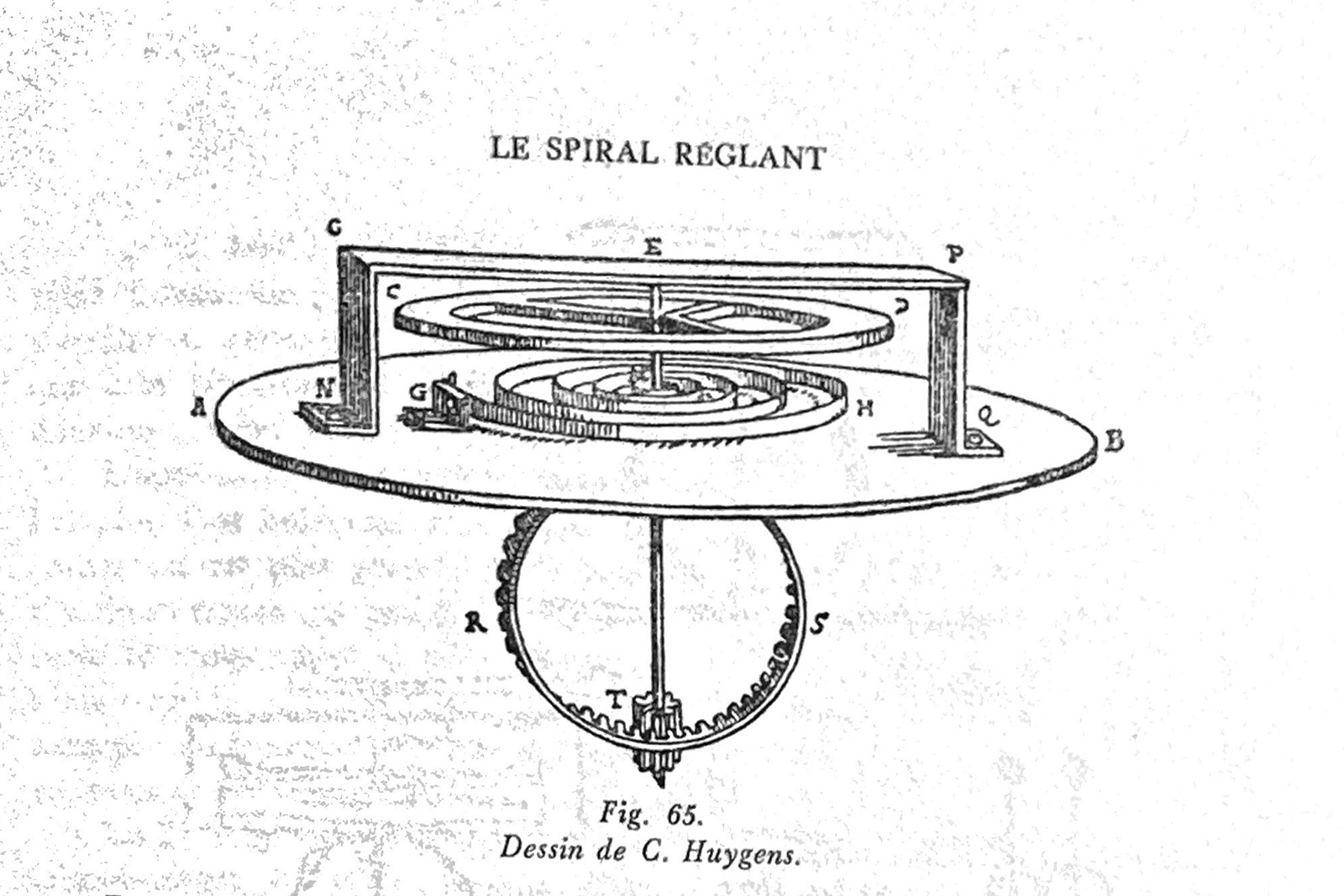

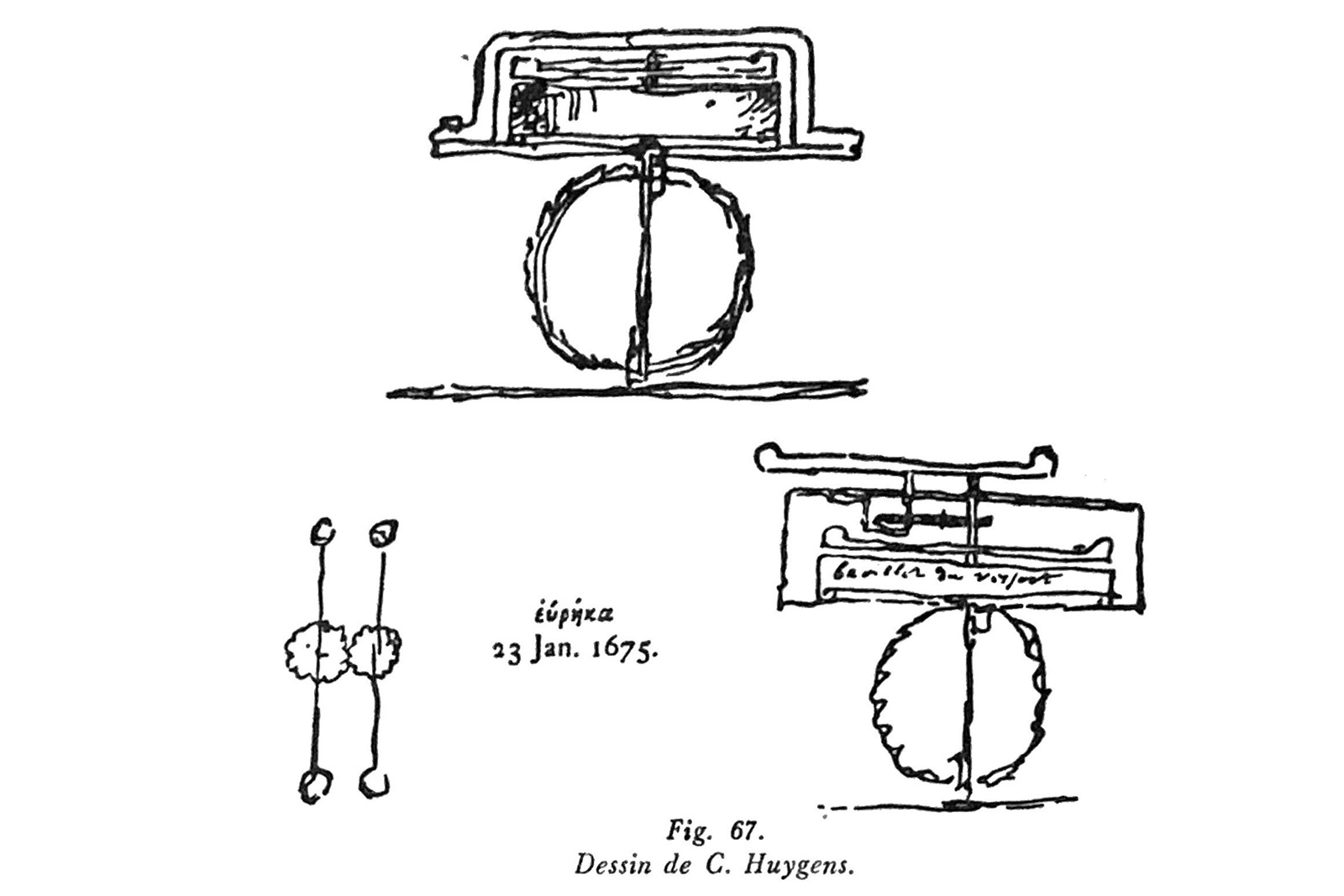

The hairspring as we know it was first devised by Huygens on the January 20, 1675. Leopold Defossez recounts in his excellent book Les savants du XVIIe siècle et la mesure du temps, Huygens’ first models had a spiral spring, made of iron or copper, with five to six turns and with its inner end solders to the balance arbour. Its outer end was pinned to a plate. In Huygens’ own words, “The spring must stand in the air in the drum and be riveted to the side and to the shaft; the ring-shaped balance as in ordinary watches”, referring to the plate and balance bridge assembly as “drum”.

Figures 65, 66 from L. Defossez

On January 22, 1675, Huygens commissioned a Parisian watchmaker to build a working model for him as a proof of concept, and on January 30, he publicly announced his invention, the hairspring, by a note sent to Henry Oldenburg, Secretary of the Royal Society. The letter contained an anagram: “axis circuli mobilis affixus in centro volutae ferrae”, which translates as “the axis of the mobile disk attached to the centre of an iron spiral”. This seemingly simple concept has been defining the horological (and to some extent the larger) world ever since.

Defossez considers the invention of the hairspring as instrumental to watchmaking as was the introduction of the pendulum, only less than 20 years earlier. The fact that both devices were devised by the same scientist is baffling.

Figure 67 from L. Defossez. Further improvements of the hairspring assembly, including a double balance, imagined by Huygens

The main dispute

In one of his works from 1677, Robert Hooke talks about some 20 ways of pairing an inertial body (balance wheel) with springs of different shapes and sizes, without fully describing any of them. It is important to note that nothing from his vague explanations was close to what we have come to know as a spiral hairspring.

Hooke also claimed somewhat defiantly that he knew some more better ways of pairing a spring to a balance wheel for a making a very good oscillator, but that he kept them secret so he could personally profit from their eventual implementation. He also claimed to have developed all this in the early 1660s, preceding Huygens by a considerable margin and thus claiming priority.

All that we know about Hooke’s sprung balances comes from his lectures Lectiones cutlerianae, where he indeed spoke about the possibility and advantages of paring springs with inertial bodies for creating oscillators.

In the Philosophical transactions published in 1675, Oldenburg writes that he was certain Hooke made some timepieces according to his claims, without ever publishing that portion of his work.

Plate from Hooke’s “De potentia restitutiva or of spring” paper

Hooke responds by saying this indeed was the case and that he openly discussed the clocks with the public during the Sir John Cutlers Lectures in 1665. When talking about these lectures, Hooke actually refers to what was spoken there, rather than the printed courses.

The definitive edition of those lectures came out in 1679 and was a collection of six treaties printed between 1674 and 1678 (as per Defossez). The treaties contain no description of Hooke’s application of springs to balance wheels.

An account by William Derham, a fellow of the Royal Society and a colleague of Hooke, describes Hooke’s sprung oscillator as follows: “a tender straight spring, one end whereof played backward and forward with the balance”. This system differs widely from Huygens’ hairspring.

Defossez was convinced that Hooke made some watches with a sort of sprung balance before Huygens, but he is confident there is no definitive evidence that Hooke ever made a timepiece using anything similar to a flat coiled hairspring

The other disputes

While Huygens is credited for the invention of the spiral hairspring, his priority was chiefly disputed by Hooke and also by the French Isaac Thuret and Jean de Hautefeuille. We covered some aspects of the Huygens-Hooke dispute and now we’ll touch a little on the other two individuals who played a part in this tale.

Isaac Thuret was a talented Parisian watchmaker which held the title of Horloger du Roi, or “Watchmaker to the King”. Thuret was a renewed manufacturer of precision clocks (which were made according to Huygen’s principles). He was the one tasked by Huygens to build a proof of concept model of a hairspring timepiece on January 22, 1675, two days after the Dutchman announced his invention.

Thuret built two models, presenting one of them as his own invention and even trying for a patent. His actions were swiftly criticised by Huygens and eventually the Parisian renounced his claim, apologising to Huygens, who was left with a bitter taste.

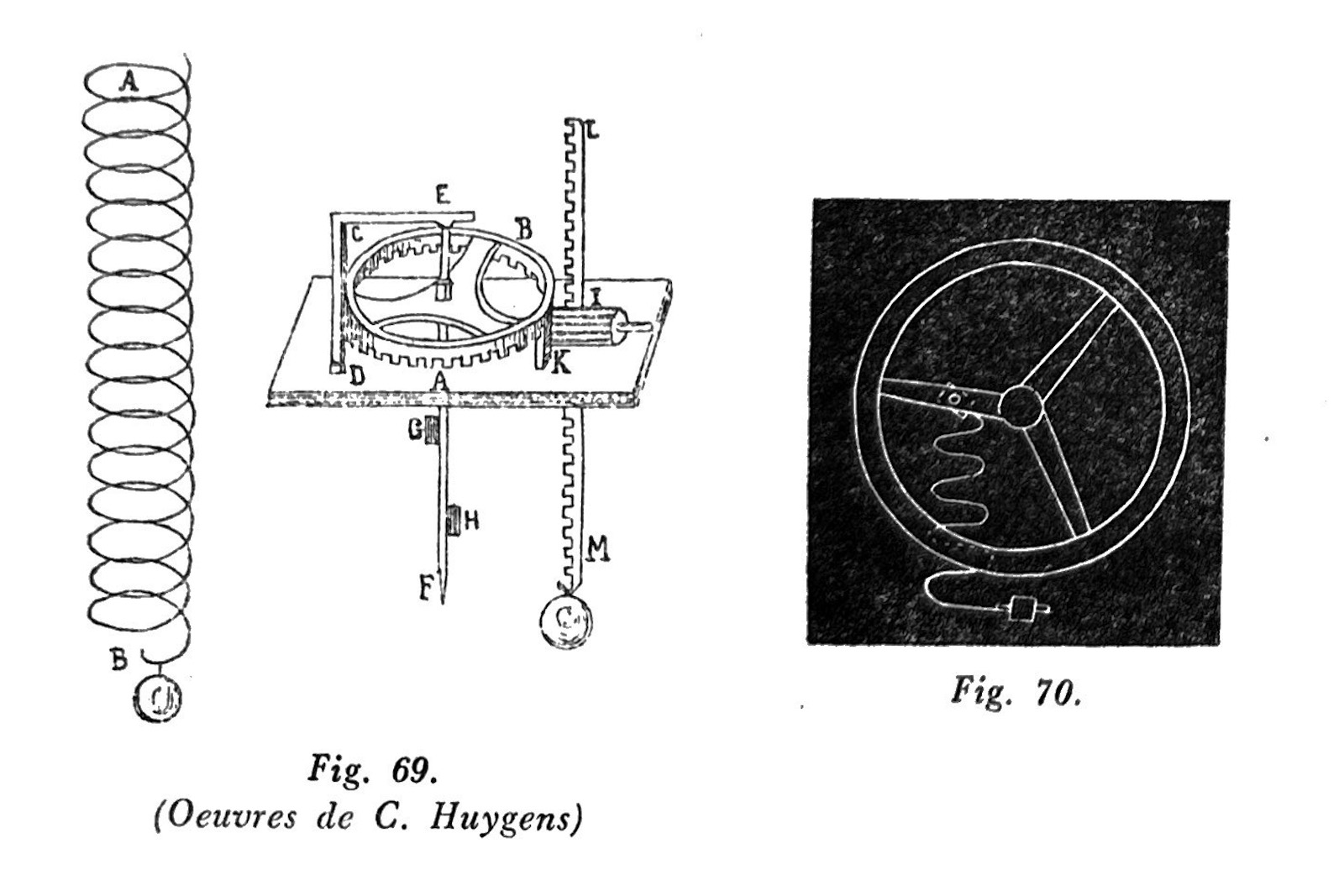

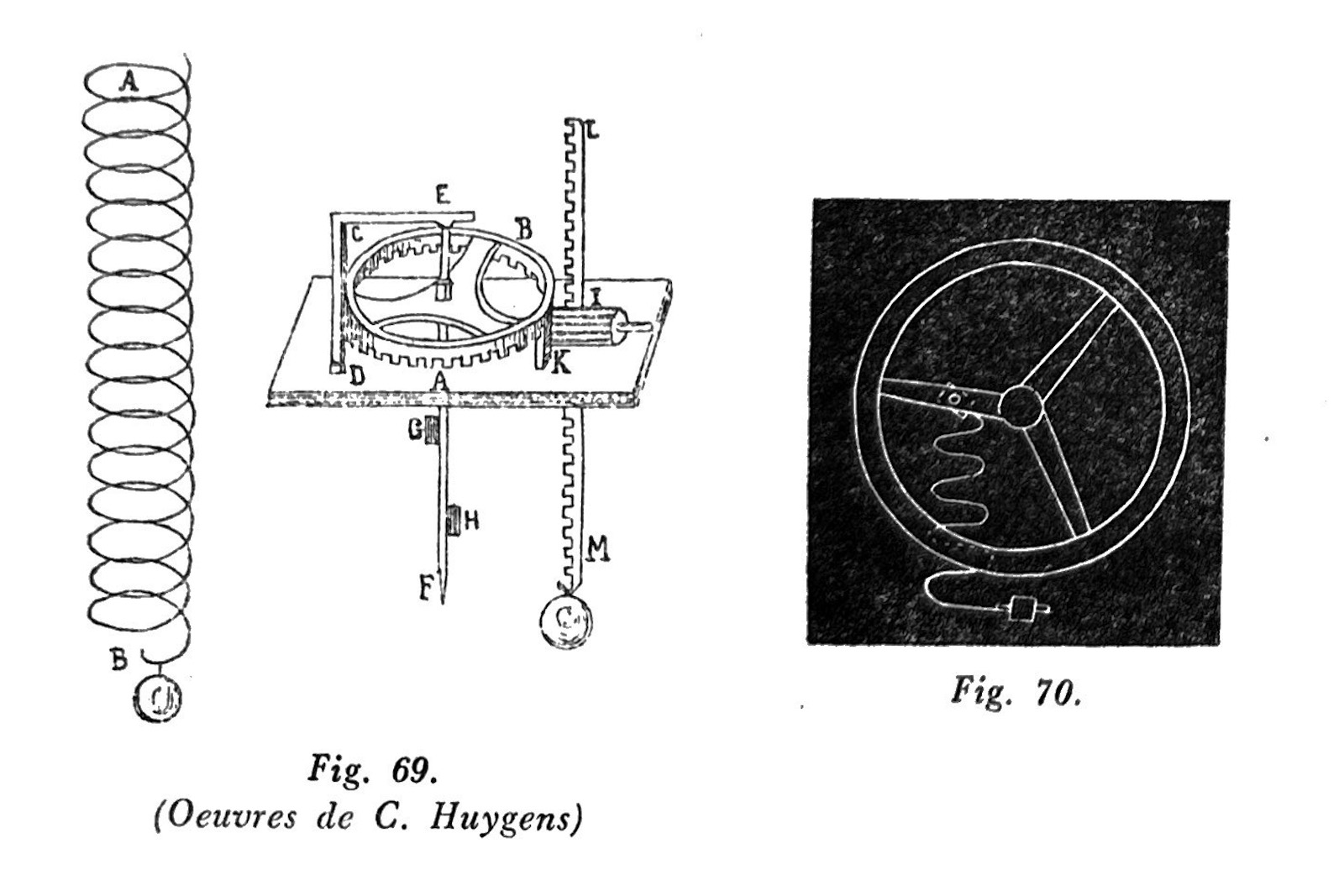

Figures 69, 70 from L. Defossez. Left figure shows Hautefeuille’s vertical oscillator and right is De Hire’s take on the sprung balance.

Jean de Hautefeuille also laid claim on the invention of the hairspring, going as far as accusing Huygens of plagiarism. Indeed, the de Hautefeuille described on July 7, 1674 in a note to the French Royal Academy of Sciences a sprung pendulum structure that could possibly work as a base unit of time measurement.

The big difference between his invention and Huygens’ balance spring was that de Hautefeuille’s pendulum was a linear system which relied on a cylindrical spring’s tensional elasticity, which would rock a weighted rack, while the hairspring was a rotational system which employed the coiled spring’s torsional elasticity in conjunction with a balance wheel.

De Hautefeuille’s claim can thus also be discarded, since the two devices didn’t work at all in a similar manner and his system never proved satisfying. Inspired by de Hautefeuille’s ideas, Philippe de La Hire came up with a sprung balance structure of his own which didn’t prove all that effective.

Conclusions

Regarding the main dispute around the hairspring, I believe it is correct to credit Hooke as the inventor of the sprung balance and Huygens as the inventor of the spiral hairspring. Indeed Hooke came up first with the idea of attaching an elastic body to the balance, but he failed to perfect the concept enough, leaving plenty of space for other innovators to invent something more definitive.

During that period there were many scientists trying to apply some sort of a spring to the clock oscillator. Even Blaise Pascal was looking into the idea in the 1660s, as was at some point the German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz. Only because Hooke eventually enunciated his famous law doesn’t mean he held any sort of monopoly over everything sprung and his reluctance to openly publish his alleged work seems to have worked against him.

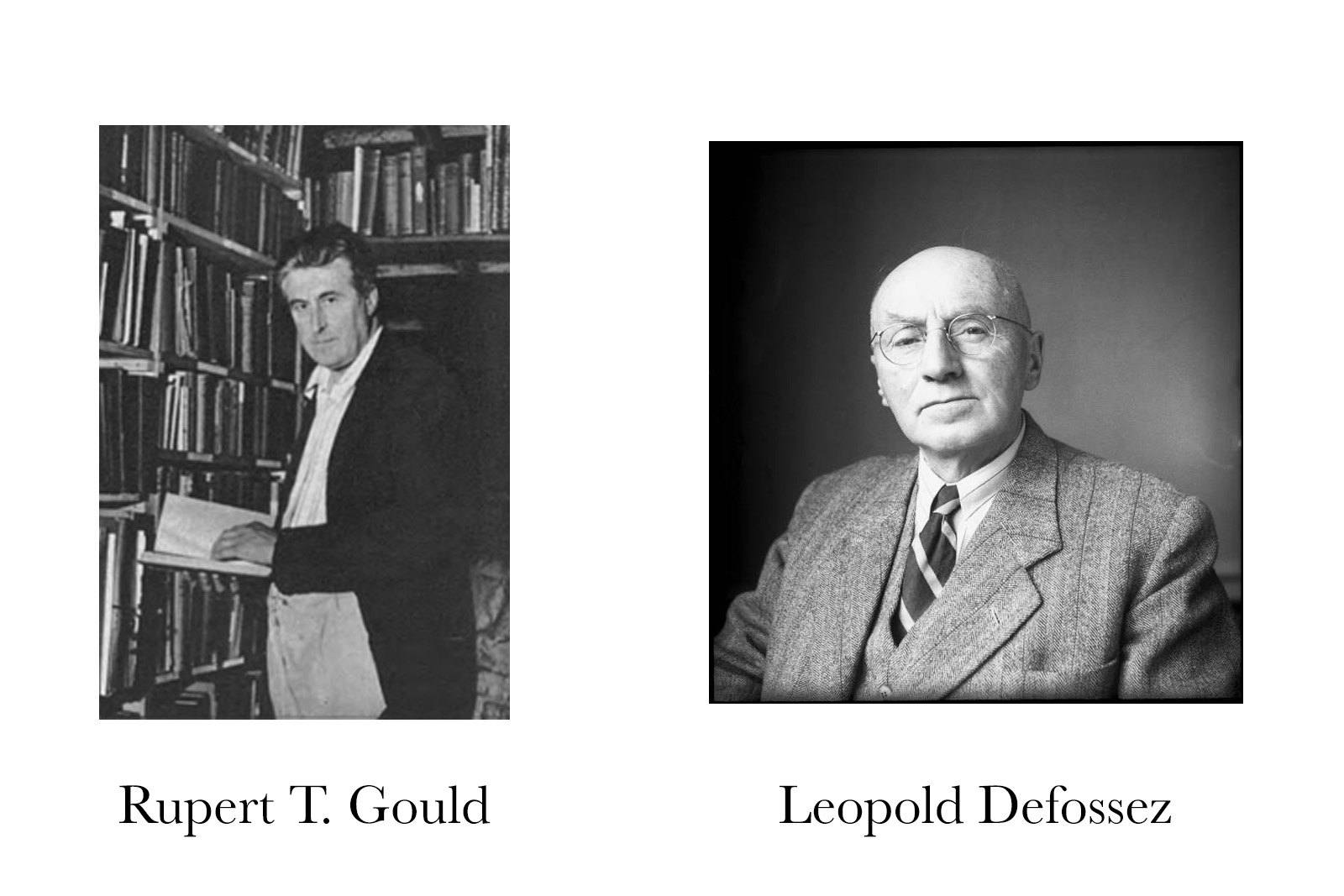

After so many years, the matter of personal preference of scholars comes into play as well. R. T. Gould openly sides with Hooke in his work, arguing that the idea of attaching a spring to the balance was firstly the Englishman’s. Defossez, however, sides with Huygens, saying that the hairspring as we know it remains entirely the Dutchman’s creation.

The two scholars to whom we owe much of what is known about the history of horology

Hooke also experimented with magnetic balance wheels in a triangular shape at some point but never reached good results (a magnetic force does not vary linearly so it wouldn’t fit well with the oscillator equation). When he presented a magnetic prototype on the May 27, 1669 to the Royal Society, the timepiece did not work properly and Hooke blamed a faulty pinion for the malfunction. There is no record of further developments on the matter. It is curious that he publicly presented the failed timepiece, but never came forward officially with a sprung balance watch.

Back in 2019, we covered Hooke’s long-lost folio: a collection of official notes from the Royal Society, one of which describes a prototype watch Hooke showed to the public on June 23, 1670.

From Hooke’s folio, the author of the 2019 story drew a different conclusion from myself. For me, Huygens is correctly acknowledged as the inventor of the hairspring as Hooke’s claims in the folio are vague and do not explain in any way how the prototype actually worked. Crucially, he did not mention if it indeed used any sort of spiral hairspring.

There is record of a spiral spring clock made by Thomas Tompion in 1675 (after Huygens’ announcement) which was presented to the king. The timepiece was bearing an inscription indicating that the principle was discovered by Hooke as early as 1658 (again, without definitive proof). This is consistent with accounts by both L. Defossez and professors I. Vardi and S. Henein. The latter two gave an extensive lecture on the subject of oscillators and their history at the Congrès International de Chronométrie 2019, hosted by the Société Suisse de Chronométrie.

Hooke never gave much more than vague descriptions of sprung balances to the larger public, and could not produce a prototype of a hairspring timepiece made before Huygens’ invention announcement. His various experiments were mostly never finished — as Gould himself states — and his method wasn’t the most reliable.

While Huygens commissioned a proof of concept two days after he completed the design of his hairspring clock, Hooke supposedly sat on the miraculous invention for about 15 years. This seems rather unbelievable, given the high stakes of creating reliable portable precision timekeepers at the time. Crowning Christiaan Huygens as the definitive creator of the spiral balance spring is reasonable, although Hooke’s contributions shouldn’t be downplayed.

Bibliography

L. Defossez, Les savants du XVIIe siècle et la mesure du temps, Lausanne, 1946

R. T. Gould, The Marine Chronometer: Its History and Development, London, 1923

I. Vardi, S. Henein, À la recherche du temps précis: la découverte de l’oscillateur, Neuchâtel, 2019

Back to top.