In-Depth: The Bexei ‘Vox Vinum’ Grande Sonnerie Wristwatch

A major work from Hungary.

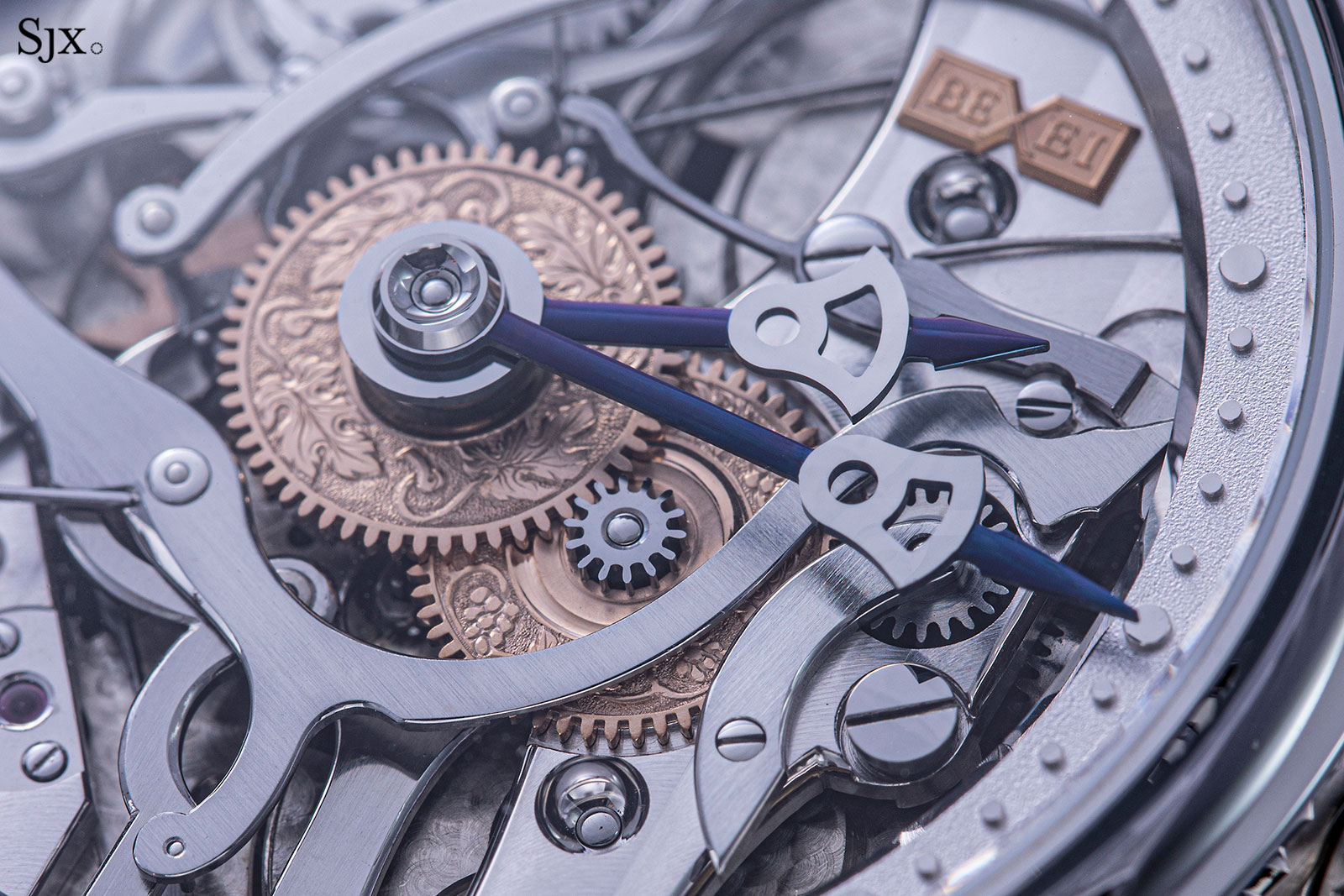

The only independent watchmaker in Hungary, Aaron Becsei, or more properly Becsei Áron, has created a distinctive style for his eponymous brand, Bexei – ornate, Gothic engraving; a double-ellipse case; and top-class movement finishing. His latest creation, a custom and unique grande and petite sonnerie wristwatch named Vox Vinum, is all of the above, except in a more conventional round case.

Created at the behest of an important, Asian collector of independent watchmaking, the grande sonnerie took more than a year to complete. It is the first, and so far only, striking watch ever produced by Bexei.

The grand sonnerie

A grande et petite sonnerie – French for “large and small strike” – is widely regarded as the pinnacle of mechanical watchmaking. Also known as a clockwatch, it strikes the hours and quarters en passant, as they pass. And it is also a minute repeater, being able to chime the time on demand.

Modern day grande sonnerie wristwatches are exceedingly rare – the number of watchmakers having produced one can be counted on both hands. The most notable makers of grande sonnerie wristwatches are Patek Philippe with its Grandmaster Chime, F.P. Journe with the recently discontinued Sonnerie Souverain, and Greubel Forsey as well as Vacheron Constantin, both of which use the same base movement in their respective grande sonnerie wristwatches. But the pioneers in the field were Philippe Dufour in 1992, and followed shortly after by Gerald Genta in 1994.

Besides a grande and petite sonnerie, the movement also boasted a tourbillon, perpetual calendar and automatic winding

Though only just completed, the Bexei Vox Vinum grande sonnerie is powered by a finished pocket watch ebauche that’s over a hundred years old – which was the starting point of the commission, as the owner wanted the base to be a classical movement.

Consequently, the Vox Vinum is similar to a 19th century grande sonnerie pocket watch in function and sound – except the movement decoration has been executed to a tremendously high level.

As it was with all classical grande sonnerie movements, the ebauche used for the Vox Vinum has two barrels and going trains, one for the time and the other for the striking mechanism. But unlike many pocket watch grande sonnerie movements that had the winding click and spring sitting on top of the barrel ratchet wheel – usually a signature feature of the grande sonnerie – this movement has the click and spring positioned beside the barrel ratchet.

The Vox Vinum can strike the time in passing, but also on demand as a minute repeater. The repeating function is activated by a pusher at 12 o’clock, while the slide at six o’clock selects the strike mode: grand strike, small strike, or silent.

And the button at four o’clock is for engaging the time-setting mechanism; the crown is otherwise only for winding, turning it in each direction winds either of the two barrels thanks to a crown wheel on a pivoted, rocking arm.

Here’s a clip of the striking mechanism in action:

Bexei of Buda

The third generation in a family of watchmakers, Aaron finished his first clock in 2003, having learnt the trade at school and also from his father, who owned a watch and clock repair business. But wanting to create his own watches, Aaron also studied computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing at the Hungarian Chamber of Engineers, where he graduated with honours in 2005.

Bexei, named after the anglicised version of his last name, is now based in two workshops in Budapest, each five minutes from the other. Some time next year, both locations will be merged into a new building that’s now under construction. With about 3000 square feet of space, the new workshop will be able accommodate all of Bexei’s employees and equipment, as future expansion.

Besides Aaron and his wife, Eszter, who handles administration and management, the company recently grew to four employees – a newly hired mechanical engineer who develops and modifies the production equipment, a CNC programmer, a watchmaker who does assembly, and an artisan who performs movement finishing.

Aaron himself still does a lot of the watchmaking, but having a team allows him to spend more time developing new watches. Annual output is now between three to five watches, with Aaron only planning to grow modestly to perhaps ten in several years.

Building the case

The Vox Vinum started with a commission from its owner, who was already the owner of several Bexei watches, but wanted something to top them all. Specifically, the owner wanted to Aaron to start with a vintage, Swiss ebauche.

So it began with an ebauche produced by Compagnie des Montres Invar, a watchmaker in La Chaux-de-Fonds founded by watch entrepreneur Achille Hirsch, who also owned a host of other watch brand names. Active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Invar made its own movements, including this one.

As an ebauche, or movement blank, a major amount of work was needed to complete it, both in terms of filling in the blanks with newly produced parts, as well as refinishing and reshaping the old components. But first, the style of the watch had to be decided. This would have an impact on the movement, as you’ll soon discover.

Being an ebauche for a full sized pocket watch, the movement diameter was about 46mm, or about 21”’, but the owner wanted a case that was as small as possible. At the same time, the case had to maximise the volume and resonance of the chimes. So Aaron had to apply some creativity in building the case, which was done entirely in-house.

To make the case as small as possible, the movement had to be first shaved down slightly. By reducing the edges of the base plate and bridges to the minimum practical size, the movement was reduced by about 1mm, allowing for a case of 46.3mm in diameter. That’s only about half the thickness of a conventional case, a feat Aaron managed by making the case more of a shell.

Thin-walled and hollow on the inside, the case has the movement sitting snugly against its sides. According to Aaron, the thinness of the case also enhances the sound of the sonnerie. As a result, the case is one piece, almost like a cap over the movement, so the movement enters and exits via the front, which is secured by a screw-down bezel.

Because of the shell-like construction, the lugs are separate – each lug is actually three pieces – and secured to the case by lateral screws. Despite being joined, the tolerances between the lugs and the case are tight enough that the finished whole almost appears seamless.

But not only do the screws secure the lugs to the case, they extend into the base plate and hold the movement in place. Positioning the screws was especially tricky according to Aaron, because they had to screw into the movement at exactly the right spot, where they would not reach any of the moving parts.

The pusher for activating the repeater, integrated into the lugs and flanked by blued titanium screws that also secure the movement

To minimise the footprint of the watch on the wrist, the lugs are short with a steep curve downwards, so the grande sonnerie wears reasonably well for a watch that large. And the fact that the case is steel and hollow also means it’s fairly lightweight, which improves the ergonomics.

Aaron also tweaked other aspects of the case to minimise its perceived size. The bezel is concave to reduce its bulk, while the sides of the case are gently convex so as to avoid the verticality of a thick case with flat sides. And the crown was made large, making winding easier but also to keep it proportional with the case.

Decorating the case

Aaron has a strong eye for decorative detail, and that is obvious in the case.

To create some colour contrast, the functional elements of the case – slide, buttons, crown and screws – are made of heat-blued titanium. Aaron opted for the lightweight alloy instead of traditional blued steel because titanium does not rust, while steel can.

And like much else in the watch, the titanium parts are all finished by hand. The pushers, for instance, have polished tops and bevels, and brushed sides.

Especially complex and impressive is the oversized crown. It’s made of steel, but topped with a blued titanium cap that’s secured from the inside with screws.

The cap is there to hold a 1.2 carat, princess-cut diamond cabochon that sits almost flush with the cap – a most discreet way of incorporating a large diamond into the watch.

And just as it was for the lugs and other components, custom-made tools were built to finish the cap. In this case it was a rod to hold the cap, plus a block with a spherical divot that’s thinly covered in abrasive paste, in order to mirror polish the curved edges of the cap.

One of the few elements of the watch not done in-house was the engraving of the case and a few wheels of the movement, though it was done locally by a Hungarian artisan who is Aaron’s go-to specialist.

Covering both flanks of the case, the engraved motif depicts grapevines, because the owner of the watch loves wine. That also explains the name of the watch – vox vinum is Latin for “voice of wine”.

More unusually, the underside of the lower pair of lugs are engraved with the first names of the watchmaker and engraver, done at the request of the owner.

According to the owner, his bespoke or custom watches usually carry the signature of the artisans who worked on the watch. In the owner’s collection, it’s often the signature of the enamel artist on the dial – the owner has a fondness for enamel dials – but here the owner wanted the engraver to sign his work, which is rarely done in watchmaking.

Remaking the ebauche…

Reducing the diameter was only the first step in the long process of finishing the movement blank. Once completed, the movement totalled over 400 parts.

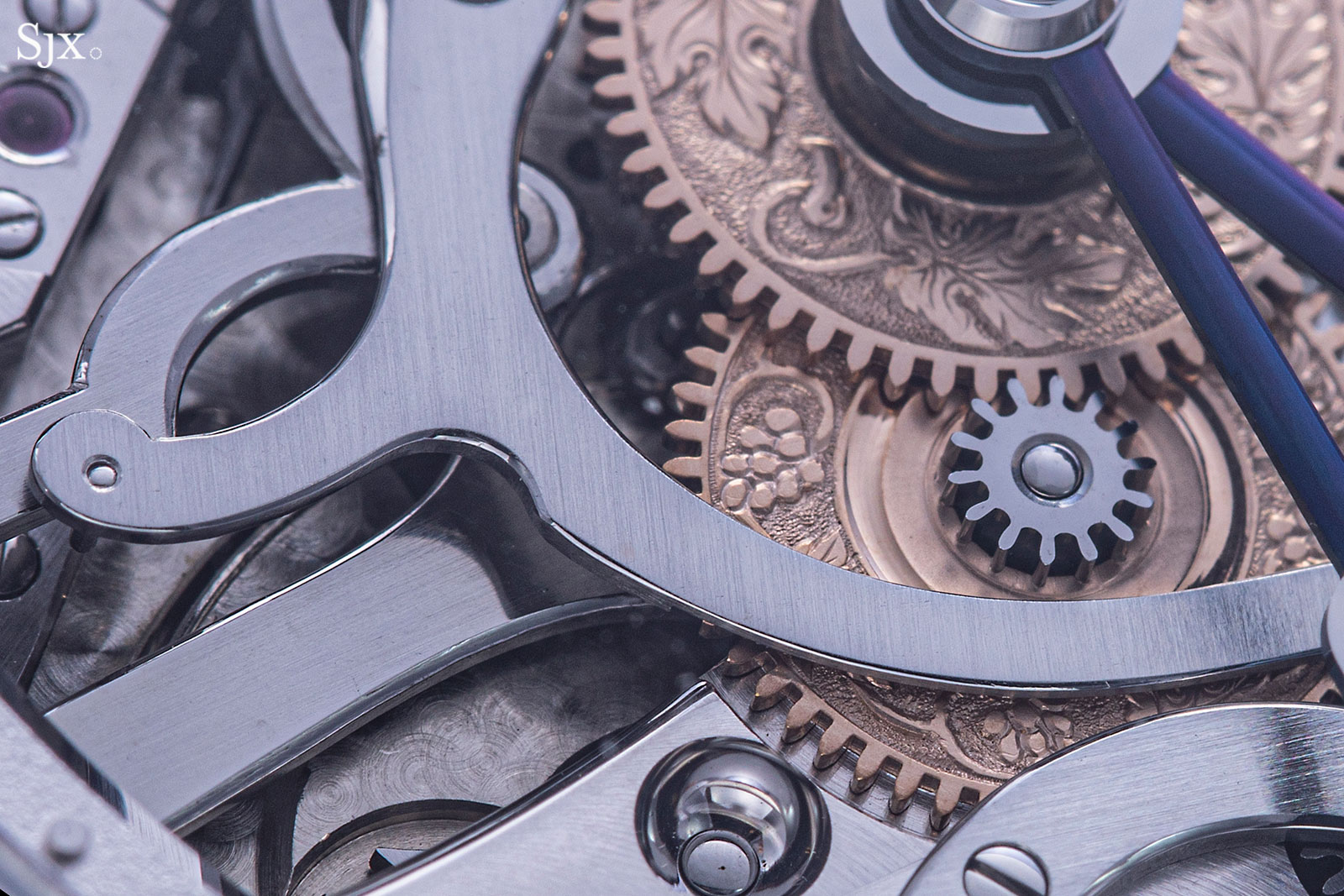

Many components had to be produced from scratch, including many screws, which Aaron turns in-house, starting from raw steel bars. Aaron also to fabricate some bridges, while others had to be reshaped to conform to Bexei’s elaborate style emphasising flourishes in the bridge shapes.

Most of the important, large bits of the original movement, including the hammers, gongs, centrifugal governor, and bimetallic balance wheel, were retained but entirely refinished.

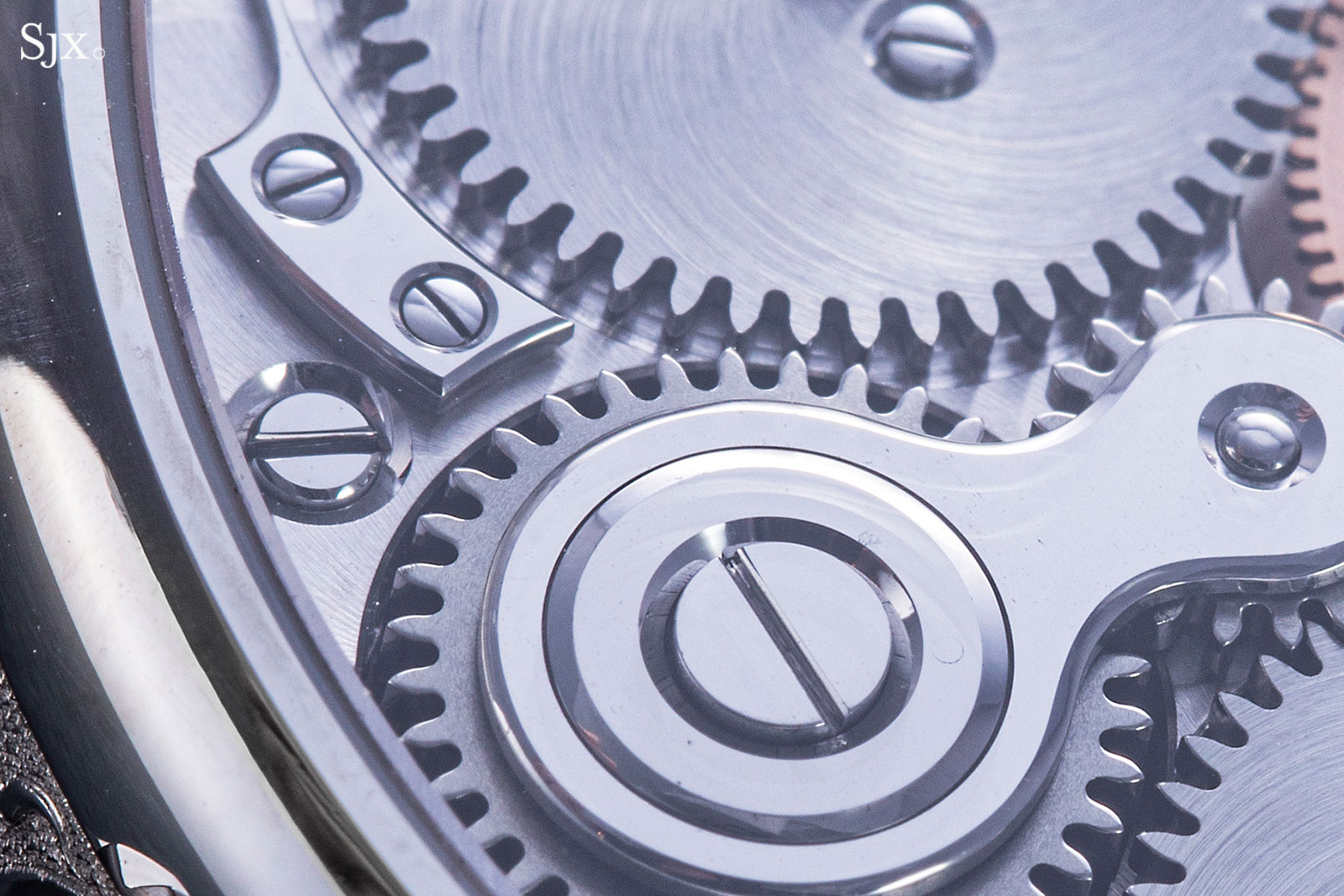

Notice the lovely bowl-shaped anglage on the countersinks for the screws on the barrel ratchet wheel

But the revamp of the movement was more than cosmetic.

One of the important, but obscure, improvements Aaron made to the movement was the installation of a KIF shock resistance mounting for the balance staff jewel, illustrating his attention to even the smallest details. Shock absorbers are often neglected in refinished vintage movements – which usually don’t have them – but important in a wristwatch, which is subject to more impacts than a pocket watch.

And the KIF spring was not merely removed from its packaging and installed; according to Aaron the spring was polished before use.

And dressing it up

One of Bexei’s key strengths is its movement finishing, and this lives up to expectations. A great deal of effort was expended in finishing the movement, right down to its most minor components.

The movement is hand finished to a high standard, one that’s amongst the best today. Bridges are decorated with Cotes de Geneve and anglage, wheels have grained faces, chamfered spokes and inner edges, small steel parts are black polished and chamfered, large steel parts are straight grained and chamfered; the list goes on.

High-grade finishing is already tedious on a brand new movement, but Aaron points out that finishing the steel components original to the 19th-century ebauche was especially difficult as the steel is harder and more difficult to achieve a mirror finish on.

At high magnification, a handful of inconsistent spots in the finishing can be found, but they’re more likely the result of the movement’s age than anything else.

The large gold chaton for the centre wheel jewel that’s secured with screws that have mirror polished, rounded heads

Even the chapter ring bearing the minute markings on the edge of the dial is finely decorated. Attached to the base plate of the movement with screws, the chapter ring was first milled on a CNC machine to create the rough shape, which included the raised minute markers.

First it was given a frosted finish, and then each minute marker was individually finished by hand – chamfering to create a sloping, bevelled edge, followed by black polishing, both on the flat tops and the chamfers.

Also finished to a similar degree are the hands, which both have a bell-shaped tip, a reference to the striking movement. The hands are first milled on a CNC machine, then filed, rounded, polished and blued by hand.

Concluding thoughts

The Bexei Vox Vinum Grande Sonnerie is a strikingly impressive watch, no pun intended. The skill and effort expended in its completion is tremendous and obvious; the rigorous quality of work marks Aaron out as one of the leading talents of his generation.

Granted, Bexei’s Gothic house style is an acquired taste; the look is heavy and ornate (and sometimes reminds me of Dracula). But the style works well with the grande sonnerie, probably because of its size and complexity, but can feel a bit much on the simpler Bexei watches.

But most importantly, Aaron is still a bona fide independent watchmaker – he owns the entirety of his company – which is usually a crucial factor in long-term success.

Buying a Bexei

Aaron’s entry-level Dignitas, a time-only wristwatch in a double-ellipse case, starts at about €60,000.

He has not yet made another striking watch – and this grande sonnerie is a unique piece – but a repeater or sonnerie built in a similar manner to the one above would cost between €300,000-500,000.

Because Aaron offers a high level of customisation, the price for an individual watch can vary substantially. Bexei watches are available only direct from the company.

Addition October 23, 2019: Added a description of the grande and petite sonnerie complication, as well as the brands that have made such wristwatches. Also included the origin of the ebauche, Invar of La Chaux-de-Fonds.

Back to top.