Watches once owned by prominent personalities are captivating. Paul Newman’s “Paul Newman” Daytona, the Rolex “Bao Dai”, Buzz Aldrin’s Speedmaster Moonwatch, the Henry Graves Supercomplication, and even J. Pierpont Morgan’s lost pocket watch, are amongst most sought after timepieces in the world. In fact, a good number of the most expensive watches ever sold at auction have notable provenance, which turns a mere watch into a historical artefact.

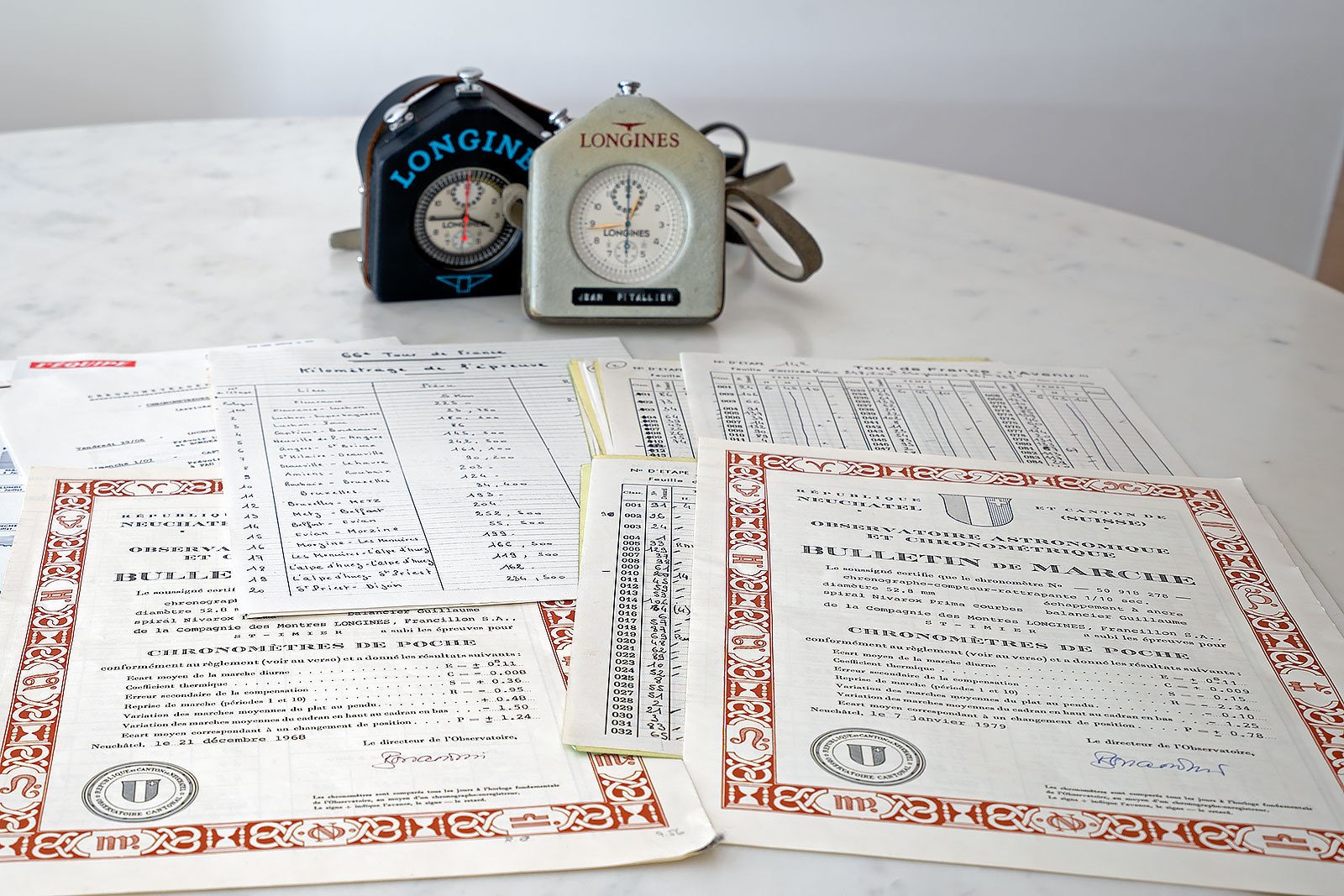

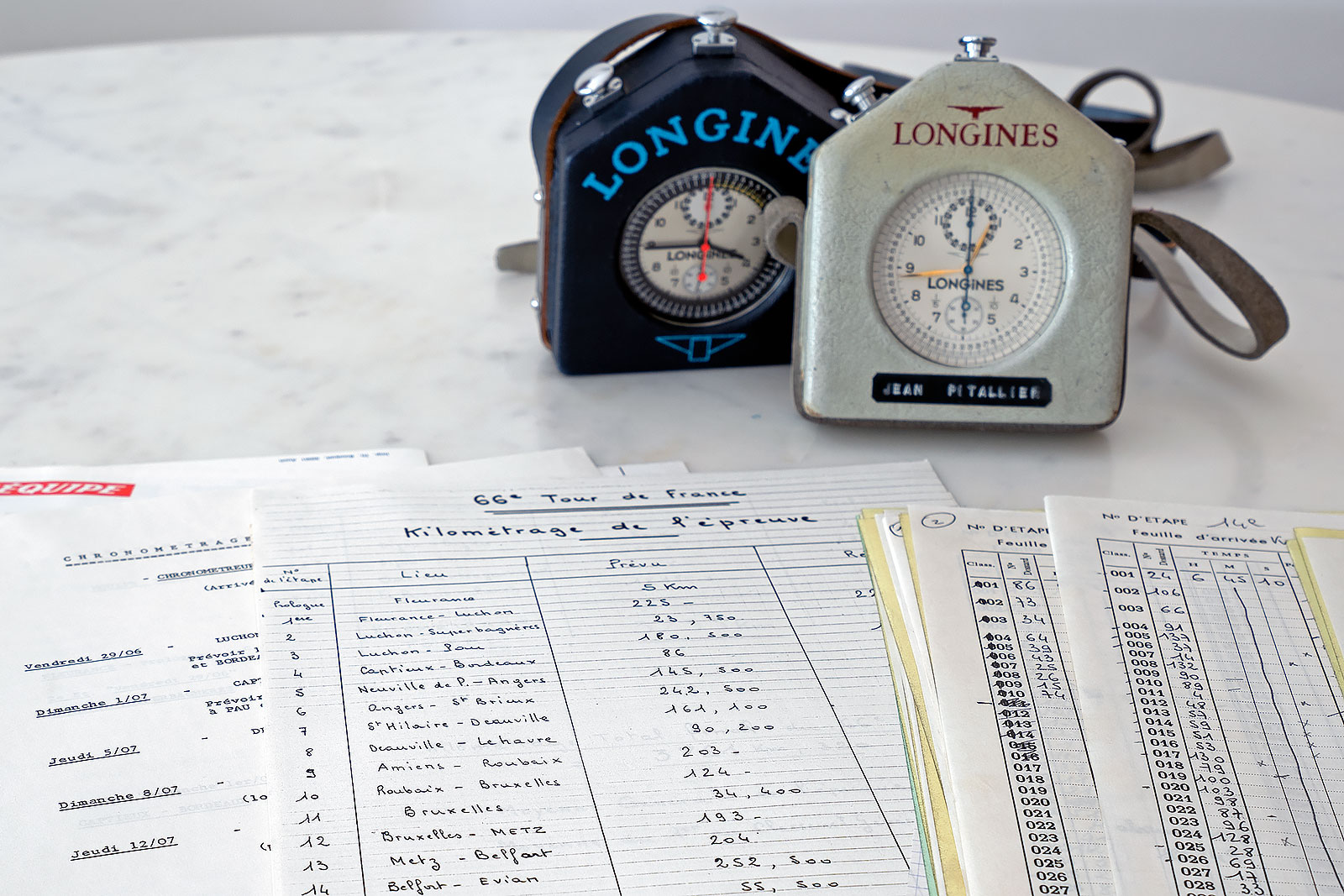

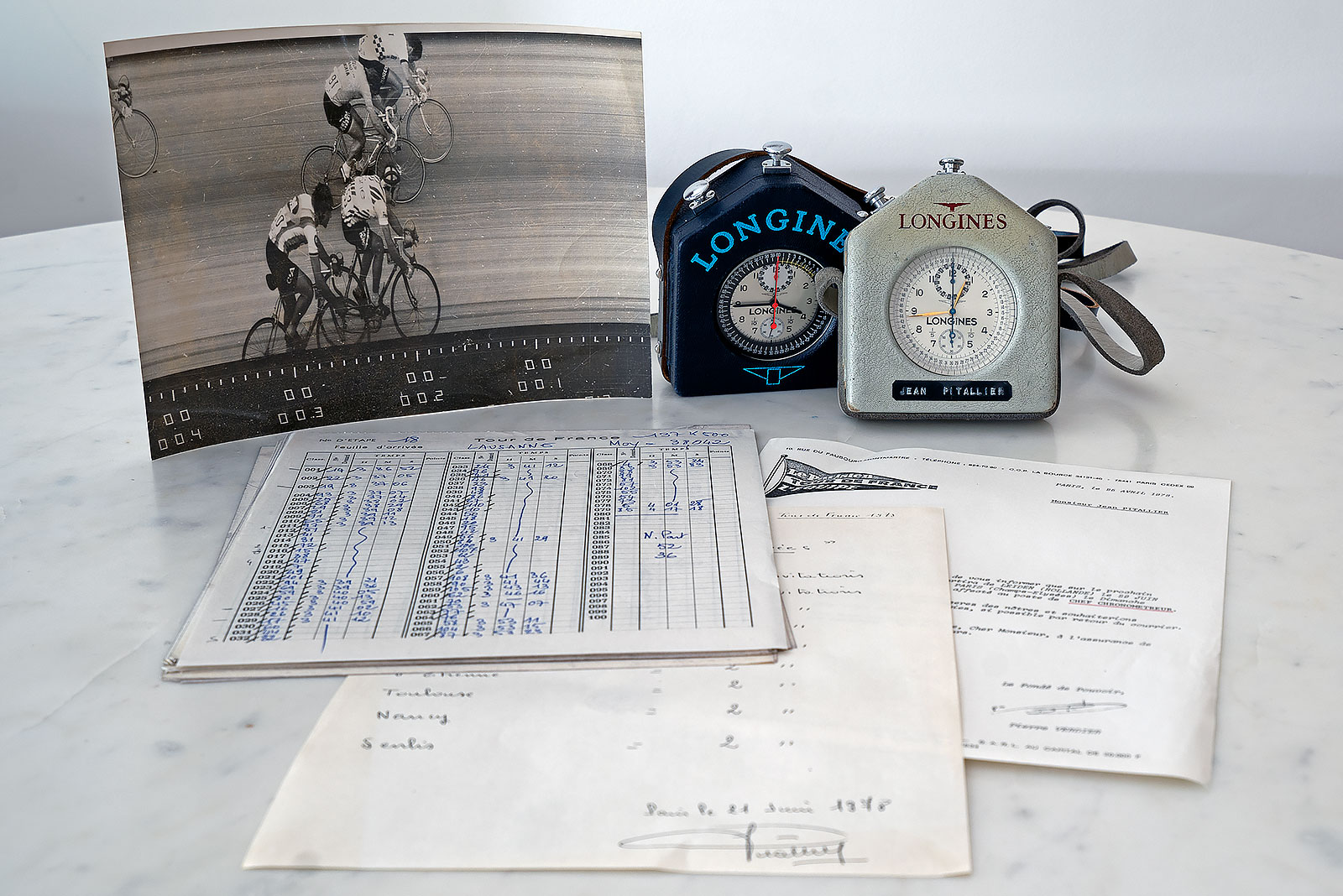

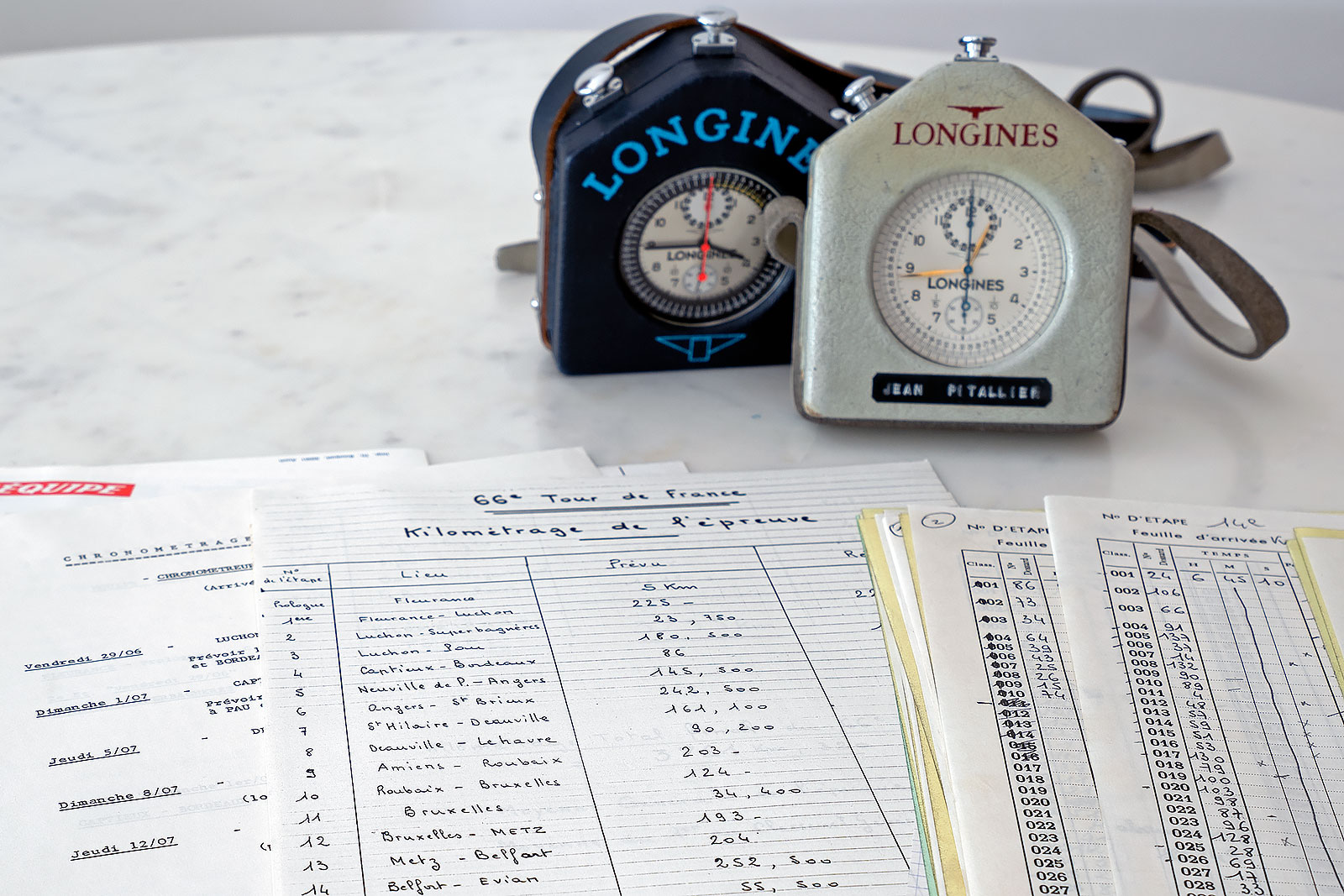

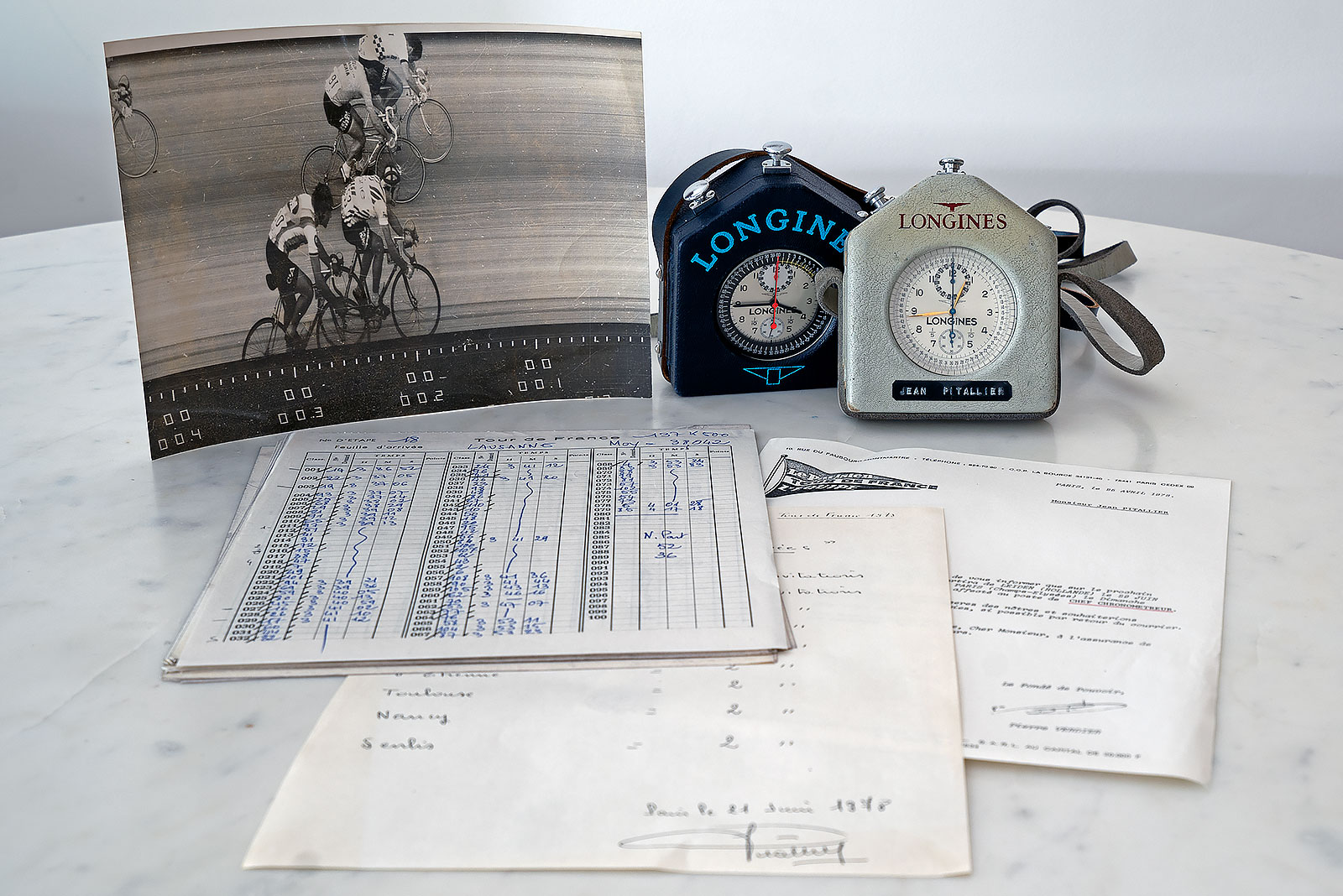

Probably the most important timekeepers in cycling, these are a pair of Longines split-seconds stop watches – refs. 7411 and 8350 respectively – that were used by Jean Pitallier, the former president of the French Cycling Federation, to time the Tour de France in the fading glory days of mechanical sports timing, just before quartz stopwatches took over.

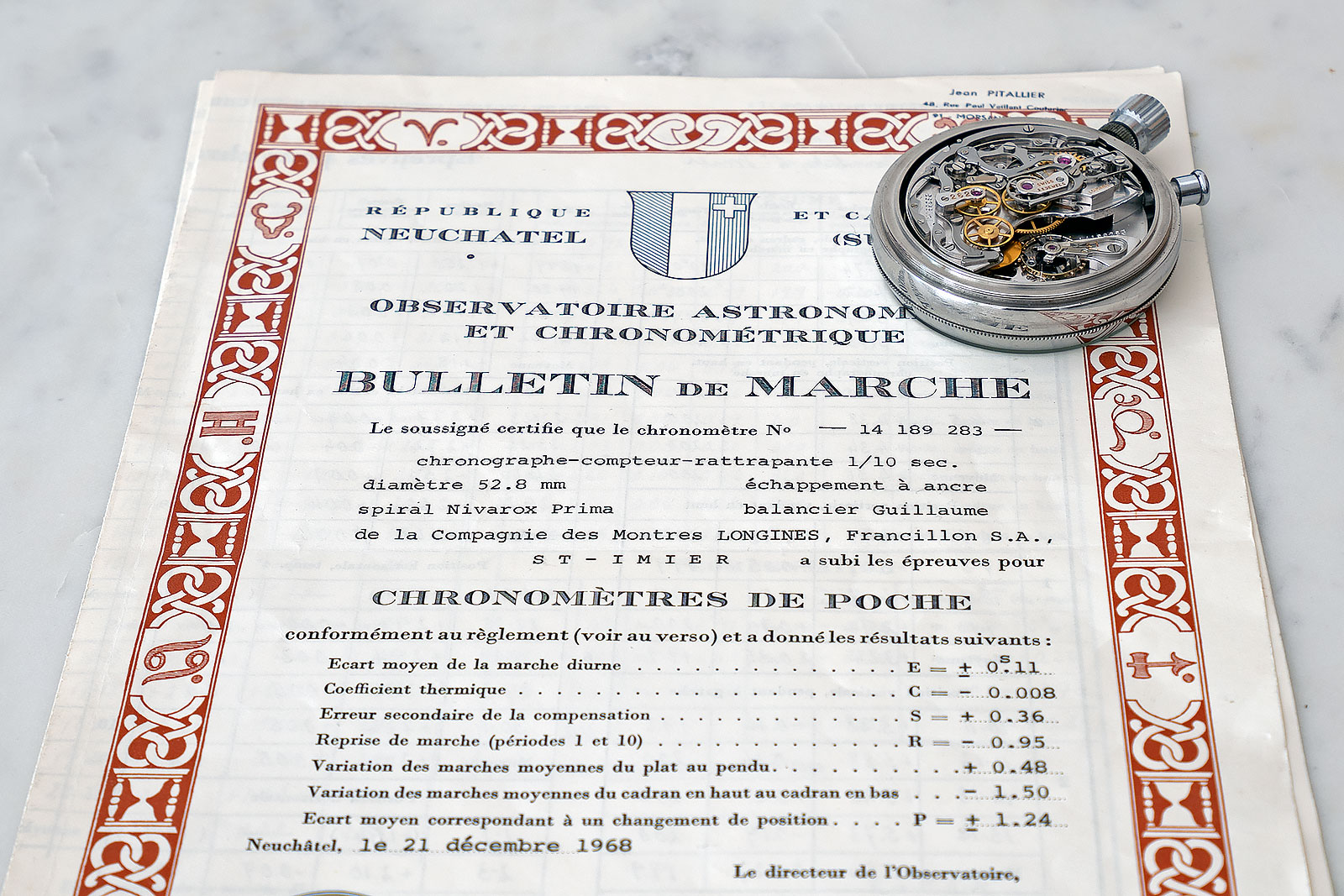

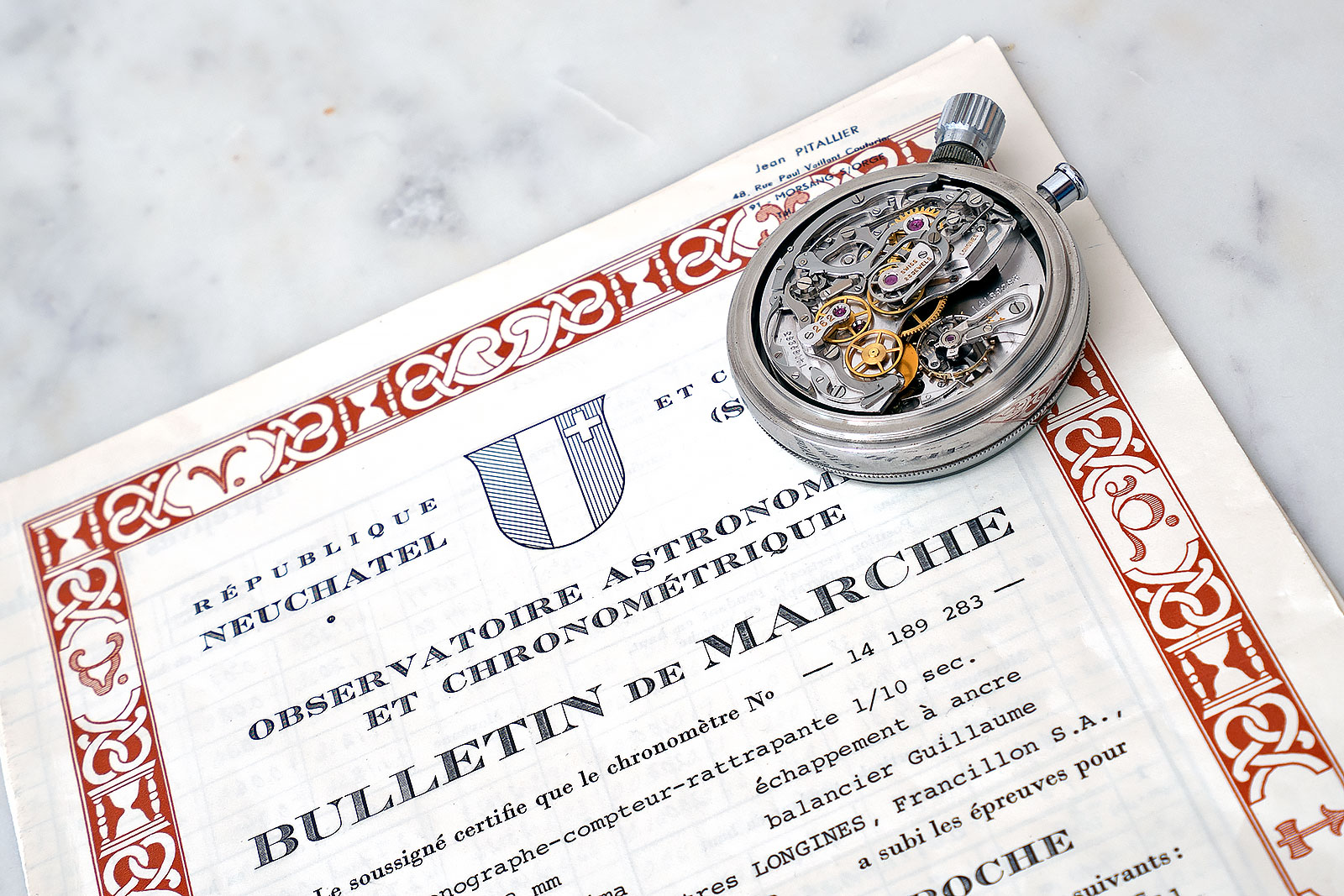

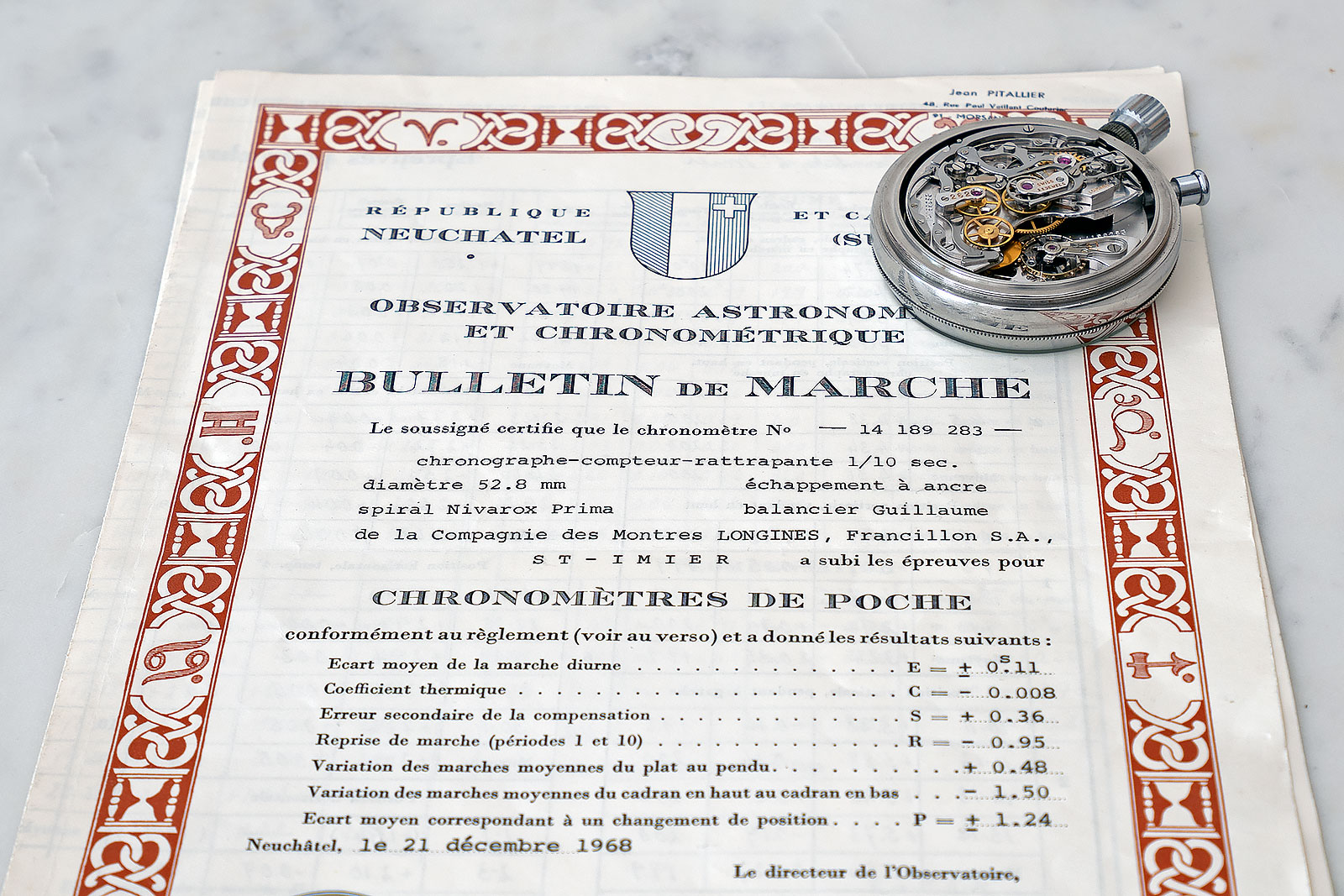

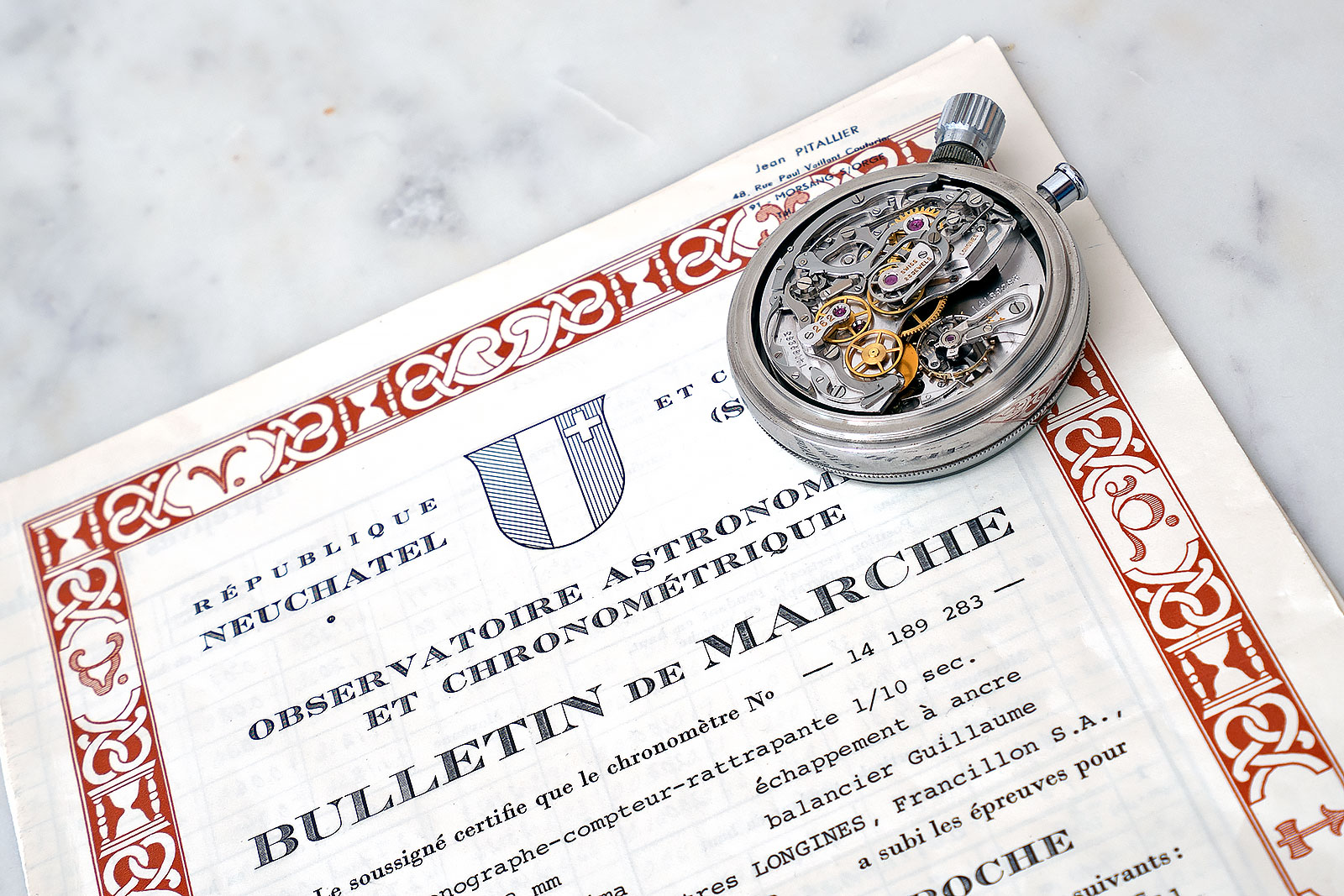

In fact, the pair of stopwatches are not merely chronographs, but also observatory certified chronometers.

Watchmaking once represented the cutting edge research of mechanical engineering. Observatory time trials at Neuchatel, Geneva or Kew were rigorous scientific affairs, with movements Peseux 260 and Zenith 135 competing to be the most accurate movement in the world.

But such movements were three-hand, time-only. Aside from tourbillon movements, very few complicated calibres were submitted to timing contests. Mr Pitallier’s pair of Longines were both certified by the Neuchatel observatory.

The swan song of competitive timekeeping

In modern day watch collecting, complications like the chronograph and tourbillon (some might argue the tourbillon is not a complication per se but that’s for another article) are appreciated and desirable because of their decorative and mechanical beauty, as well as the craft that goes into building them. But that forgets the fact that such complications they were first invented not as collectibles, but to fulfil specific, functional purposes.

Chronographs or stopwatches were used extensively in motor racing, athletics, aviation, as well as in various branches of the military. These demanding applications meant that chronographs made for professionals had to be carefully adjusted to a high standard.

The split-second, or rattrapante, chronograph was the ultimate tool for professional timing, being able to measure two independent but simultaneous elapsed times, like two cars on the track for instance. Rattrapante chronographs such as Omega Olympic ref. 6713 and various Heuer stopwatches were widely used during the Olympics and Formula 1 racing until the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Interestingly, Mr Pitallier chose to time the Tour the France not with the more common standard Omega or Heuer stopwatches, but instead a pair of Longines split-seconds chronographs.

The pinnacle of stopwatches

Large, top quality stopwatches produced exclusively for professional use, the Longines refs. 7411 and 8350 were constructed with a four-part, 67mm steel case that contains the legendary cal. 262.

Unlike modern split-second chronographs that are haute horlogerie and cased almost exclusively in precious metals – and in steel they cost even more – Mr Pitallier’s Longines are both in steel, and double-cased in fact.

Like most professional stopwatches of the era, the pair of refs. 7411 and 8350 are both housed in a protective steel case. These outer cases were designed for the stopwatch to be activated while inside the case, protecting the watch from shocks or damage during use.

The movement was conceived to be the most precise split-second chronograph on the market and it succeeded. The cal. 262, and its predecessors like the cal. 260, was responsible for timekeeping at several Olympic Games in the mid 20th century, including the Winter Olympics in Oslo (1952), Squaw Valley (1960), Innsbruck (1964), and the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. The chronograph also kept time at other major sporting events of the 20th century, including the Tour de France and Donald Campbell’s attempts to set the world land and water speed records in a rocket-powered vehicle.

In fact, the cal. 262 was some of a last hurrah for high-end mechanical timekeeping just before the Quartz Crisis almost wiped out the industry. It incorporated almost all of the technical innovations developed to perfect mechanical timekeeping, making it pinnacle of mechanical, professional timing.

The cal. 262 is manually wound, high frequency movement that runs at 36,000 beats per hour. It’s a large, robust movement with a diameter of 24’’’, or just over 54mm, with 26 jewels and a special Nivarox hairspring, self-compensating Guillaume balance and swan-neck micrometric regulator index.

More importantly, the cal. 262 also includes a remontoir, or constant force mechanism, in the escapement, to ensure stable timekeeping even with the chronograph engaged.

And the ref. 8350 even took the obsession with timing to the dial: it was equipped with a vernier scale for the split seconds hand for more precise measurement.

Complicated movements, especially split-seconds chronographs, were significantly more difficult to regulate for observatory time trials two main reasons.

For one, there is less space for the balance and gear train. Secondly, running the chronograph consumes a significant amount of energy, both instantly at the moment of engagement and during its operation, which affect the amplitude of the balance.

Yet both these chronographs managed to achieve observatory chronometer-standard timekeeping – running within 0.78 and 1.02 seconds per day respectively – during tests in four different positions and temperatures that lasted over a month.

Monsieur Pitallier

Jean Pitallier was the former president of the Fédération Française de Cyclisme (FFC), or French Cycling Federation, and a living legend in the field. A former competitive cyclist himself, Mr Pitallier occupied a string of senior positions in the federation after he stopped racing in 1962.

In fact, Mr Pitallier’s love for the sport reputedly started at age three when he first watched the Tour de France with his godfather, which eventually inspired him to become a keen amateur cyclist himself. He won five races in 1956 before he was called up for mandatory military service, where he took part in the Algeria War.

After the war, he joined national utility Gaz de France as an engineer, while taking on the roles of race official and timekeeper for Tour de France for two decades. He was elected as general secretary of the FFC in 1981 before assuming the top job at the French federation in 2001.

Elected to the FFC’s top job in the wake of a doping scandal, he served as president for nine years, a period when French cyclists won a total of 562 medals, including six at the 2008 Olympics. After three terms, Mr Pitallier did not to seek re-election in 2009, a year after a spat with the UCI over jurisdiction over the Tour de France.

Before he became management, Mr Pitallier personally timed every Tour de France from 1973 to 1980 with the pair of Longines split-seconds stopwatches, the refs. 7411 and 8350.

And he meticulously recorded everything on paper, evidenced by the sheaf of hand-written documents that accompany the watches. The lap results of all the participants and points they earned during the matches were carefully recorded and calculated as shown in the original documents. Some finish line photos were also captured to determine the ranking, in addition to the timing results.

Han Lou is a scientific research professional based in the United Kingdom and has been a watch collector for 10 years. He is particularly interested in observatory chronometers and independent watchmaking of the 1990s, and chronicles his hobby on Instagram.

Correction August 14, 2019: Amended text to reflect the fact that Longines’ stopwatches did not keep time at all Olympic Games during the mid 20th century, as stated in an earlier version of the story, but only some of them.

Back to top.