The latest from Austrian watchmaker Habring2 is the Chrono-Felix, a single-button chronograph powered by the A11C-H1 movement. Like the rest of the brand’s line-up it is smartly constructed and eminently well priced, but more importantly it illustrates the tremendous evolution of Habring2, the company founded in 2004 by watchmaker Richard Habring and his wife Maria. In fact, the tale begins almost 30 years ago, when Mr Habring first joined IWC and encountered the Valjoux 7750 movement.

Compared to the earlier timepieces of Habring2, the Chrono-Felix looks and feels a good deal more refined, both inside and out. As with all Habring2 timepieces, the best thing about the Chrono-Felix is its movement.

The architecture of the movement is based on the Valjoux 7750, the robust ETA chronograph calibre that is the most common mechanical chronograph movement in the world, with tens of millions have been produced). But crucially, Habring2 modified the construction and design to a significant degree, improving both its technical qualities as well as its aesthetics, to create a proprietary calibre named the A11C-H1.

Diving into the nuts and bolts – literally – of the A11C demonstrate the tremendous improvements Habring2 has made, creating a calibre (actually, a family of movements) that essentially boasts all of the 7750’s qualities but none of its weaknesses.

Hello 7750

The A11C-H1 inside the Chrono-Felix is the third in the A11 family of movements, which includes the time-only Felix and the Doppel Felix split-seconds.

While its construction was derived from the 7750, nearly all of the A11’s components are produced by independent suppliers, with nothing being made by ETA, Switzerland’s biggest movement manufacturer. In fact, Mr Habring is keen to point out of the dozens of different specialists responsible for the components inside the Chrono-Felix movement, only one, CHH Microtechnique in Le Brassus, is part of the Swatch Group, which owns ETA.

The 7750 is long in tooth, having made its debut in 1972 at Valjoux, a movement maker now part of ETA. It was developed to be a no-frills movement by watchmaker Edmond Capt in the midst of the Quartz Crisis, partially in response to the self-winding chronograph movements that emerged in 1969, namely the Zenith El Primero and the Chronomatic developed by Breitling, Buren, Dubois-Depraz and Heuer. Since then, tens of millions have been produced, both by Valjoux and other manufactures, since the patents on the design have long expired.

Mr Habring’s history with the 7750 is a long and distinguished one. He is best known for developing the condensed rattrapante mechanism that sits on top of the 7750 inside IWC’s many split-seconds chronograph, which made its debut in 1991. Another of his key creations was the compact flying tourbillon with a titanium cage that was installed in the Il Destriero Scafusia of 1993, the most complicated watch IWC ever made, but nevertheless based on a 7750 movement.

The cal. 18680 inside the IWC Il Destriero Scafusia

The flying tourbillon inside the Il Destriero Scafusia, with the split-seconds mechanism on the top right

“Before I joined IWC I did not know the 7750 at all,” recounts Mr Habring, “Starting to work with it brought me to the point where I preferred it over all other movements IWC used that time. And it was also an important movement at IWC, driving both the Da Vinci as well as the Grand Complication.”

“The product engineering around the 7750 done by IWC showed how universal this movement is while being probably one of the most reliable movements in the market,” explains Mr Habring.

“As somebody who generally prefers simple solutions over complicated ones, Edmond Capt’s design – which will soon be 50 years old – appears to me to be absolutely genius especially considering his age [just 26 years old] when he designed it.”

“It is also reassuring that the IWC split movement is the oldest one that is still in production that has never been modified,” adds Mr Habring, “We have to thank Edmond Capt; it proves the quality of his movement.”

Farewell 7750

But for all its strengths, the Valjoux 7750 is made to be cost-efficient in production and assembly. On the other hand, the A11C movement was conceived to be robust but also easy to repair (and not replace) long into the future. The A11 was constructed to be superior to the 7750 on several levels, spanning the entire production process.

The first level of the A11C’s superiority starts at the very foundation of the movement with the make-up of individual components, which were designed to be more long-lived as well as easier to service and adjust. Some of the changes are obvious: the A11C uses a tangential screw regulator index instead of the common Etachron.

Most of the other improvements are less obvious, but arguably more important. While many of the parts in a 7750 are welded together in a speedy automated process, the equivalent components in the A11C are separate, assembled by hand and secured with pins. An example is the chronograph cam, which in the A11C is made up of two pieces connected with a pin, as compared to three parts welded together in the 7750.

That approach also allows for finer adjustment of the chronograph mechanism, bringing about an improvement that’s tangible to the wearer – feel of the chronograph mechanism is markedly more crisp and less stiff than a 7750.

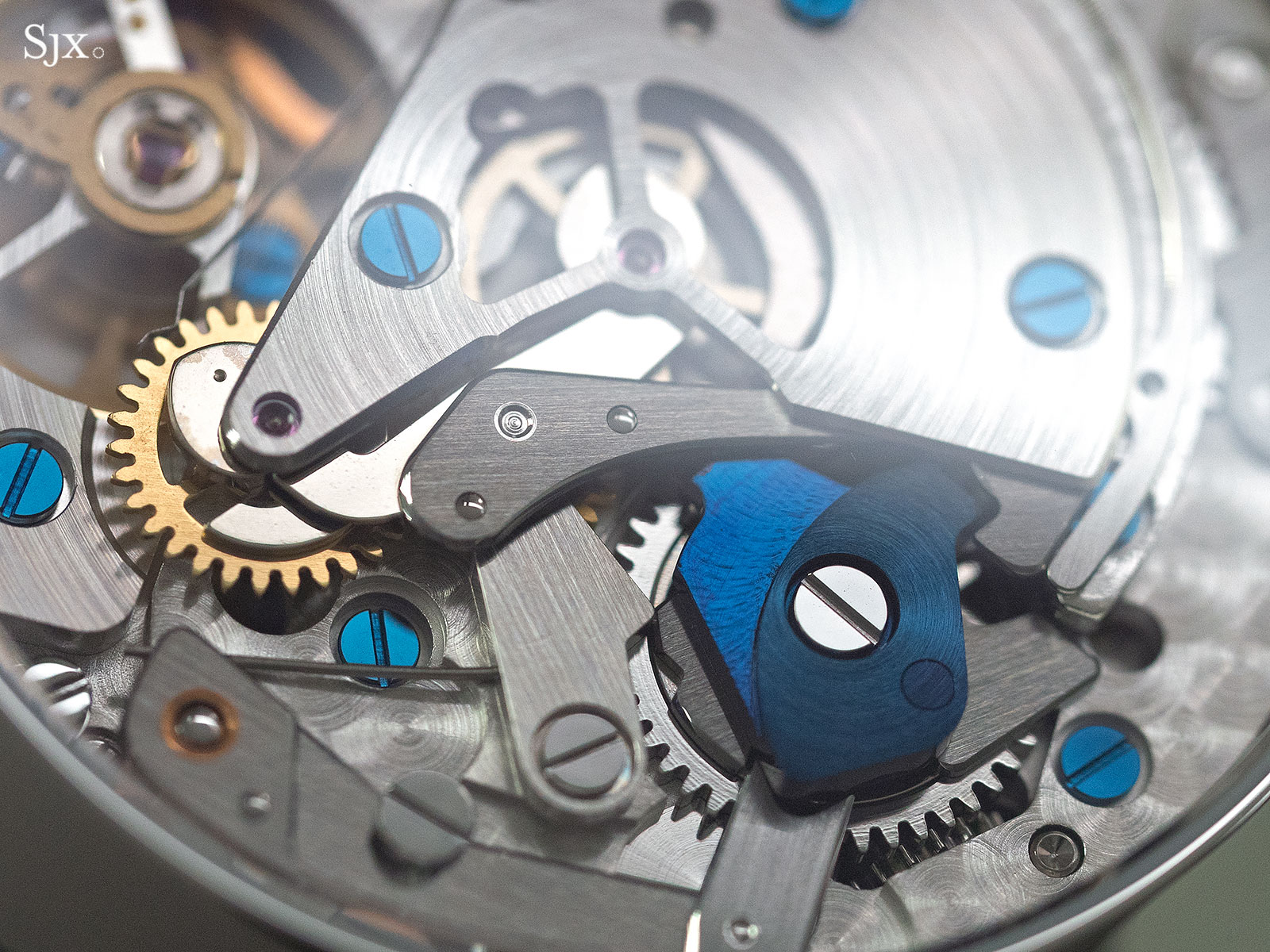

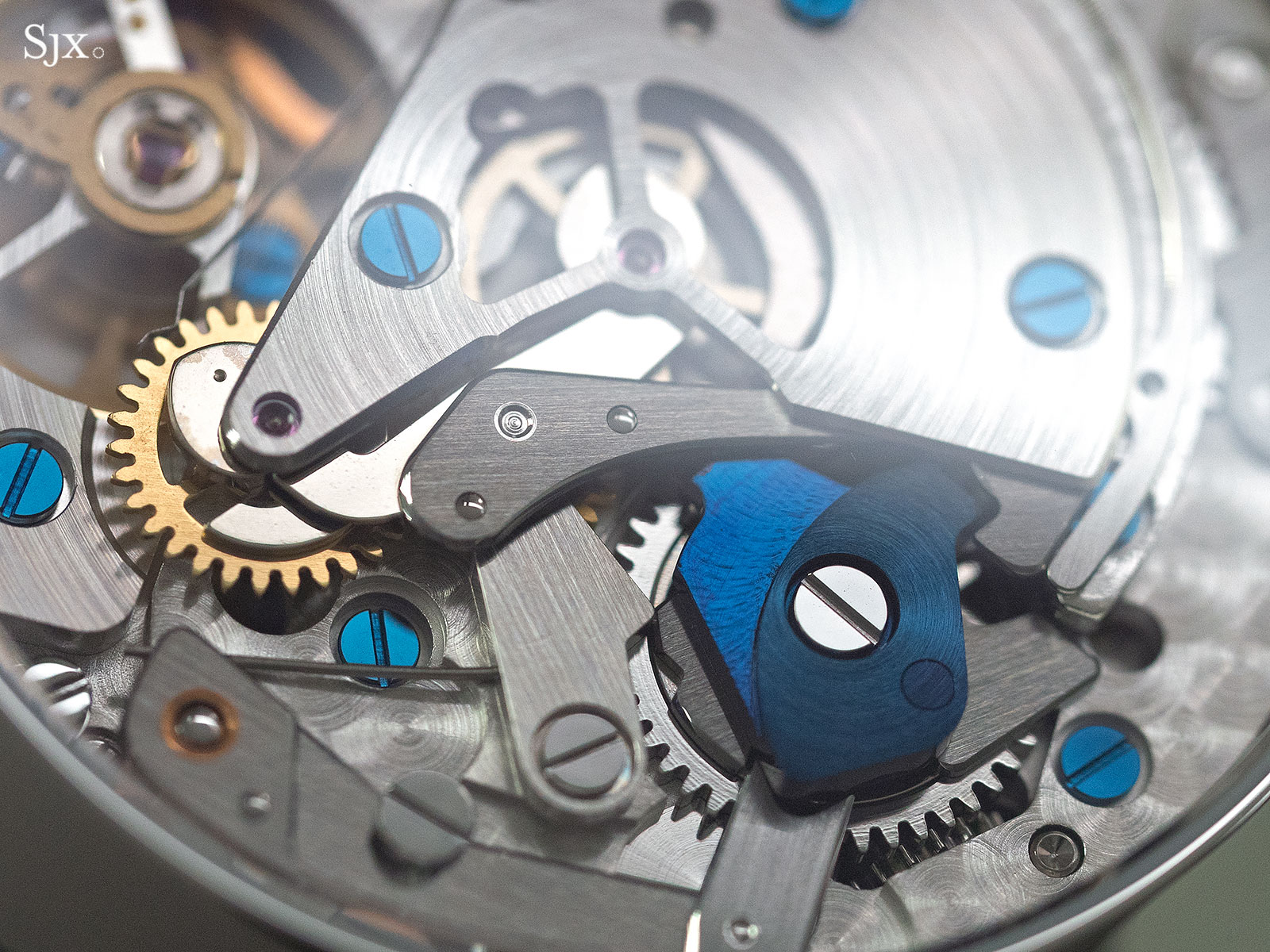

The cam in blued steel

Other improvements made in the name of robustness include a brass bushing for pin of the chronograph lever; in a 7750 it sits “naked”. Another is the use of a machined spring for the chronograph operating lever, which replaces a bent wire in the 7750.

Past the movement construction is the second level of the A11C’s prowess: the production processes used to make the parts are of higher quality. Many moving parts in a 7750 are stamped and then tumble polished, resulting in a characteristic semi-shiny, wavy surface, most obvious in the lever of the chronograph mechanism.

In contrast, the moving parts in the A11C are fabricated by laser micro-cutting, essentially where a CNC machine uses a laser to cut tiny components. This results in parts of greater precision that are also more visually attractive, appearing cleaner and neater.

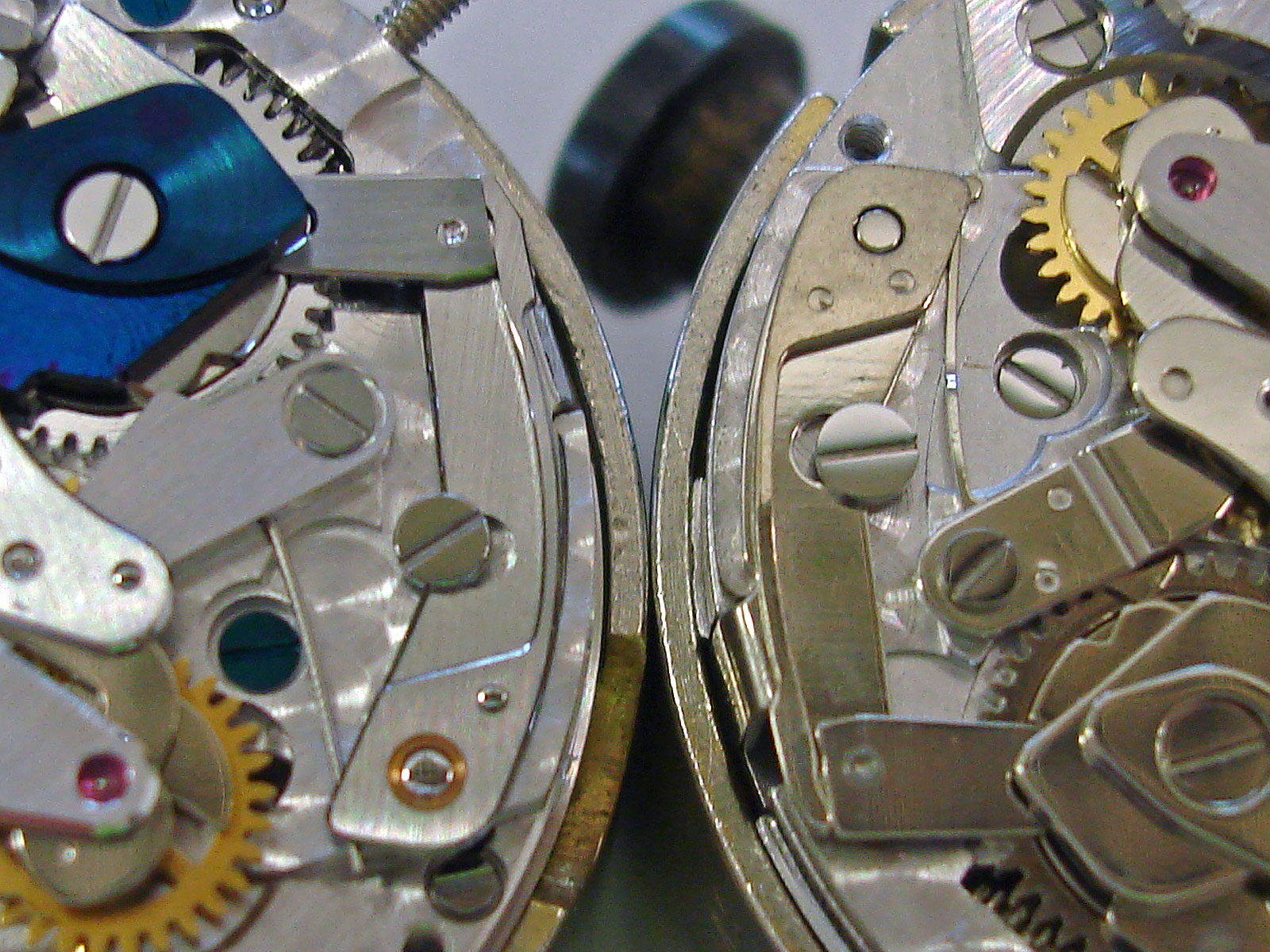

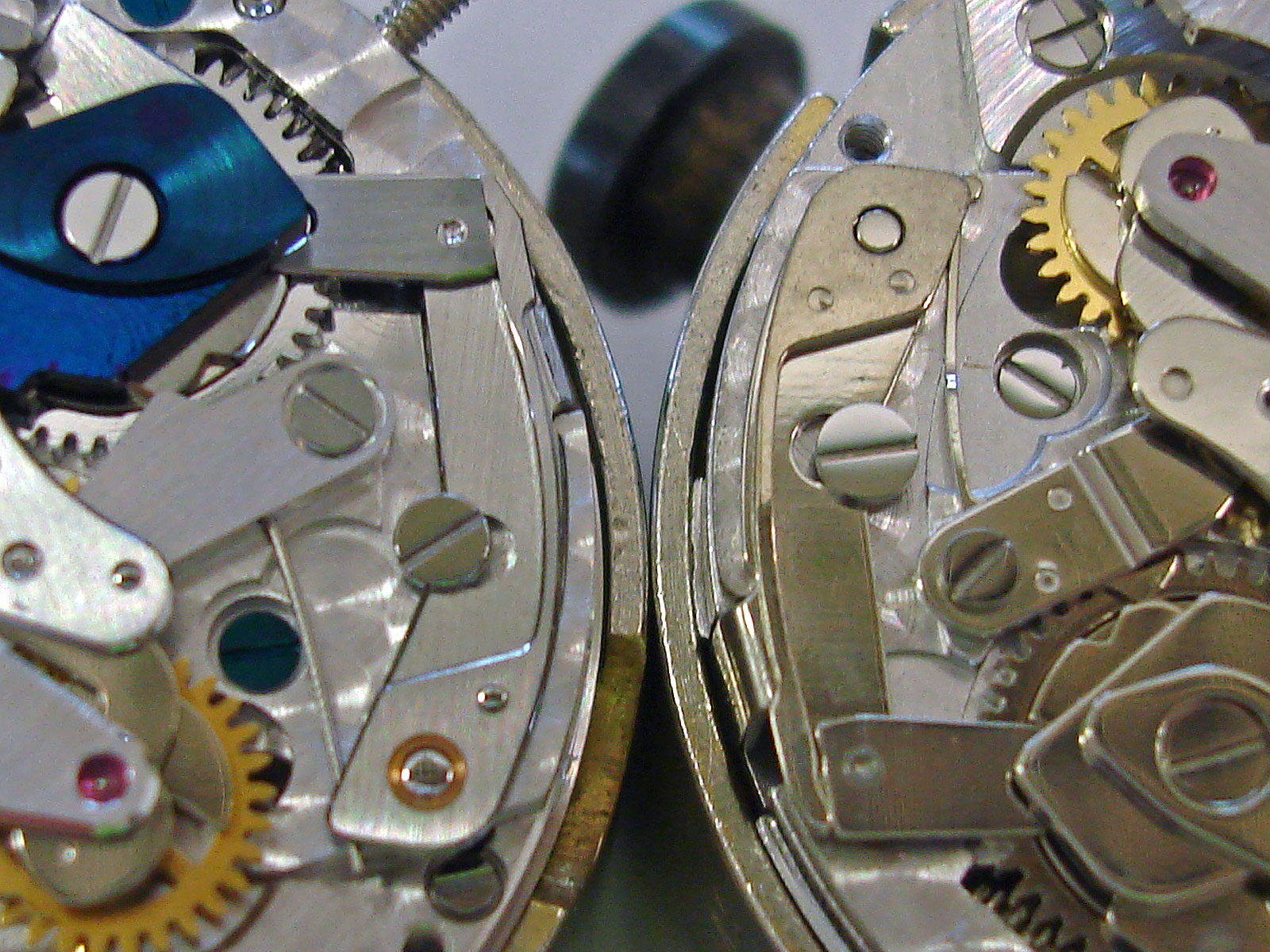

A11C on the left, 7750 on the right. Note the differences in the operating lever on the edge of the movement. Photo – Habring2

The operating lever of the A11C. Photo – Habring2

Similarly, the larger parts that are milled, like the bridges and base plate, are made to finer tolerances, giving them more refined surfaces and edges.

Dressed up

And that leads to the third level of the A11C’s revamp vis a vis the 7750 – aesthetics. The decorative improvements are arguably just as significant, because the original 7750 is so common, and so often elementary, it is entirely forgettable. But the Habring2is undoubtedly the most visually appealing 7750-derived movement in a long, long time. It looks good.

The bridges are finished with a circular graining and bevelled edges, while the base plate features perlage. Most of the chronograph levers are straight grained, with their edges bevelled and polished. The finishing is a mix of hand- and mechanically-applied decoration, but all of it is neat, careful and catches the light nicely.

A liberal use of blued steel screws, along with a blued steel chronograph cam, combined with several gilded components, gives the movement a pleasing colour palette. Even for a seasoned observer the good looks of the calibre, given its origins and price, is surprising.

The road ahead

“One important point – if not the most important – when it comes to its construction is that we had to keep a certain compatibility to the 7750 in order to use our own parts for the service or repairs of the watches we made in the past using ETA components,” explains Mr Habring. The compatibility with the 7750 also means that future servicing of the A11C will be relatively easy for a competent watchmaker, even one not trained by Habring2.

Mr Habring, however, is conscious that the use of the 7750 as a starting point inevitably brings comparisons with the low-cost movement. “We often ask ourselves whether this was the right step, especially when a first look at the movement speaks of ‘something ETA’,” he says, “Honestly we’re not sure about that, time will show.”

And it is also important to note the A11C is still being improved, thanks to Mr Habring’s endless quest for better engineering. “We are still working on further modifications, like a more refined blocking lever for the chronograph and a higher quality minute counter wheel,” points out Mr Habring, “The minute counter wheels we use now are what we have left from past ETA supplies, but by next year those will have all been used, so the new wheels will then be finished with circular graining.”

The fact that Habring2 accomplished all of that, despite the affordability of the Chrono-Felix, is an admirable achievement. “The production of such a number of components in small volumes costs a fortune,” says Mr Habring, “The ebauche of the A11C – just the parts, before assembly – costs five times more than the fully assembled 7750 supplied by ETA in the past.”

With a 7750 or equivalent priced at between US$200 to US$400, the A11C would cost well over US$1000. That means the movement is a substantial portion of the total cost of the watch, perhaps a tenth to a fifth of the retail price. That compares with the 2% to 5% of retail price that an ETA movement costs, when installed inside a watch made by an establishment brand.

Habring2 style

On the front the watch is similar to the Felix and Doppel Felix in style. Typical of the brand’s styling since its start, the Chrono-Felix has a straightforward dial design that’s vaguely retro but not distinctively so.

The dial is silvered and grained, while the hands are blued steel and to the point. The only decorative elements on the dial is the red “12” and the arrowhead minute counter hand.

At 38.5mm in diameter, the case is a moderately sized and eminently wearable. It does, however, feel slimmer than Habring2‘s earlier watches, not so much because it is actually much slimmer, but because of the design. The lugs are shorter and end in a point, the bezel is sloping and flat, while both the back and sapphire crystals are less domed. Together they help make it seem slimmer, which makes the watch feel relatively compact.

The Habring2 Doppel 3 next to the Chrono-Felix

The Chrono-Felix sitting on the Doppel 3

The modest dial and case, in contrast to the remarkably accomplished movement, are entirely in keeping with the philosophy of Habring2, which emphasises engineering, mechanics and instrinsic quality of the watch (and only the watch, for the strap is just plain).

Pricing

The Chrono-Felix costs €6250 including 20% Austrian sales tax, or about €5208 before taxes. That’s equivalent to just over US$6000.

For comparison, the Chrono-Felix costs a modest 10% more than the IWC Pilot’s Watch Chronograph powered by an actual 7750. The Chrono-Felix is a lot of watch – a lot of movement, actually – for the money.

It’s already available, either direct from Habring² or any of its retailers.

Back to top.