Despite being just 33 years old, Masahiro Kikuno makes wristwatches by hand in a rigorously traditional manner, inspired by the craftsmen who built wadokei, or traditional Japanese clocks, in the 19th century.

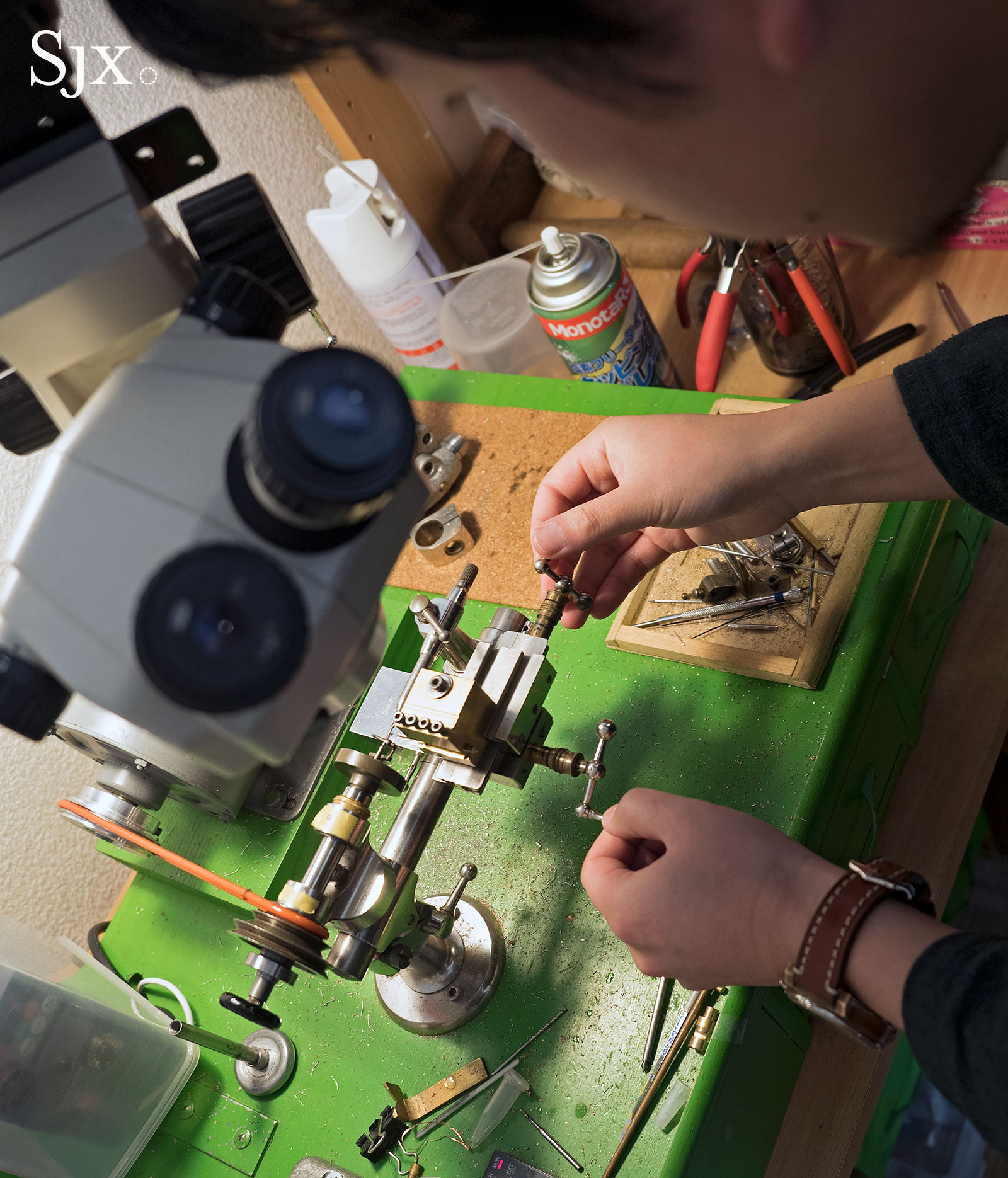

Based in the small city of Matsudo, an hour’s drive from Tokyo in Chiba prefecture, Kikuno crafts his timepieces inside his home, working in a converted bedroom, while the garage is the machine shop and the spare toilet a metal treatment facility. Shared with his wife, Kikuno’s house is compact, clean and comfortable, like many Japanese homes.

The upstairs bedroom that’s been turned into a workshop

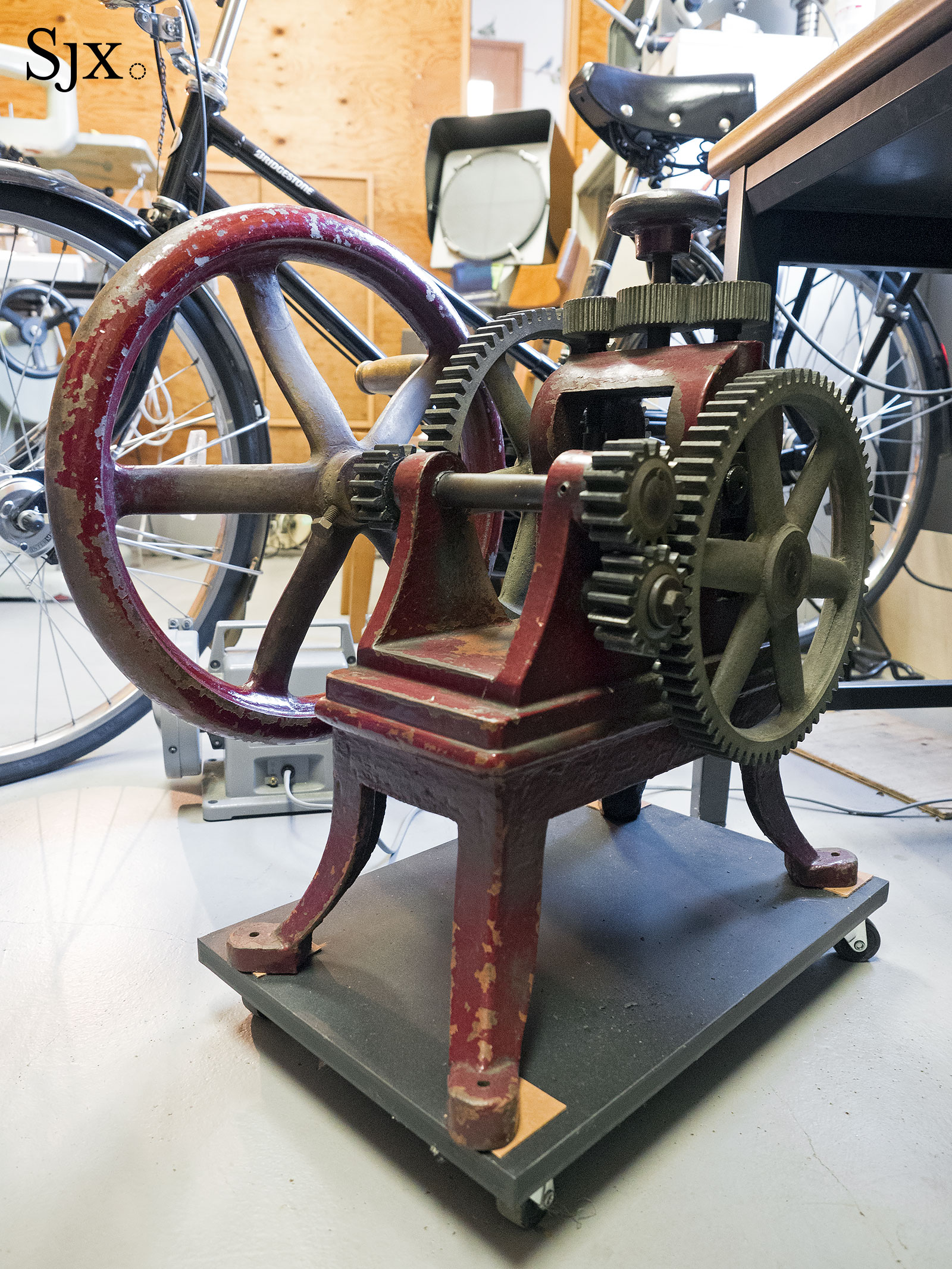

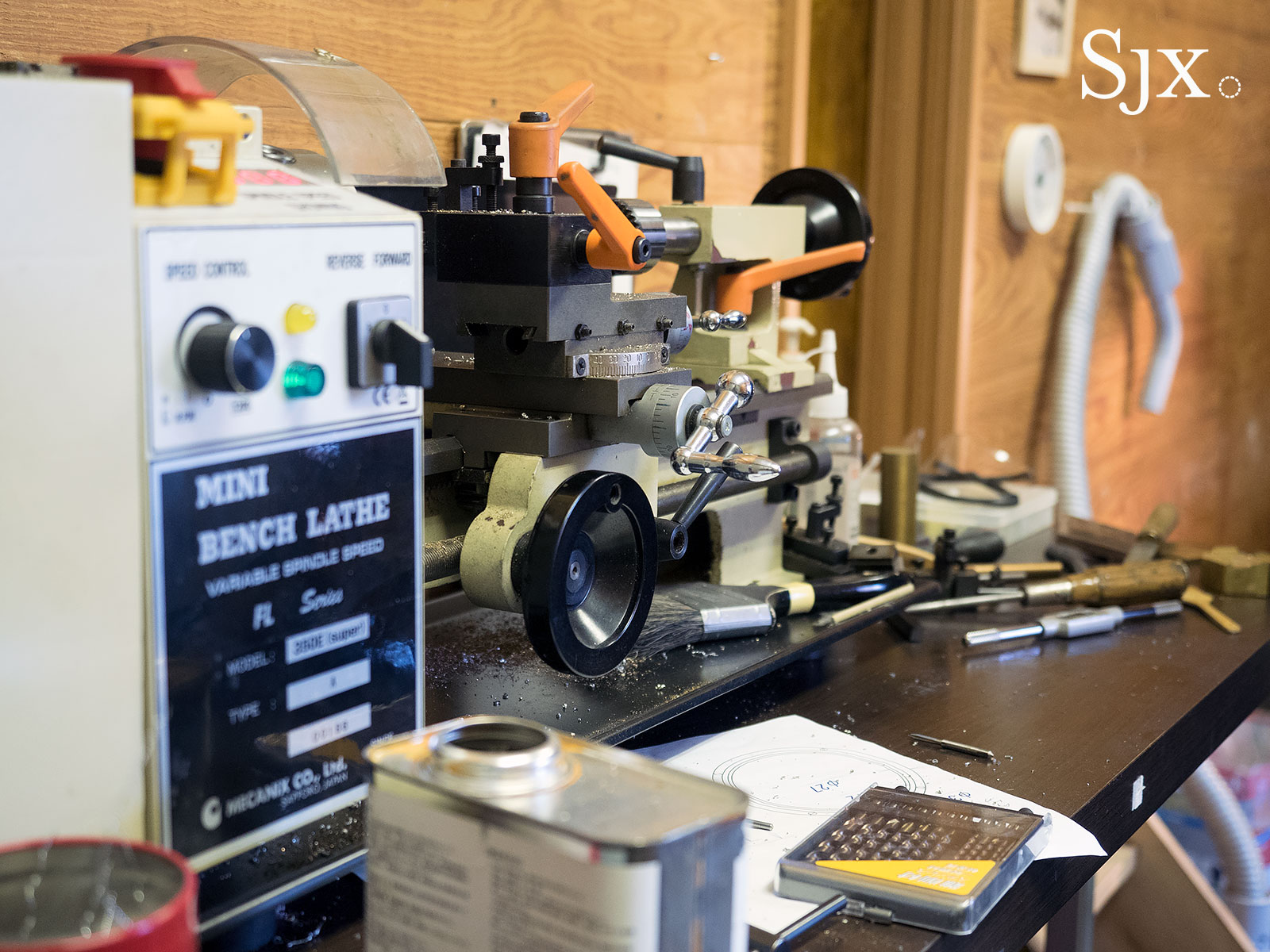

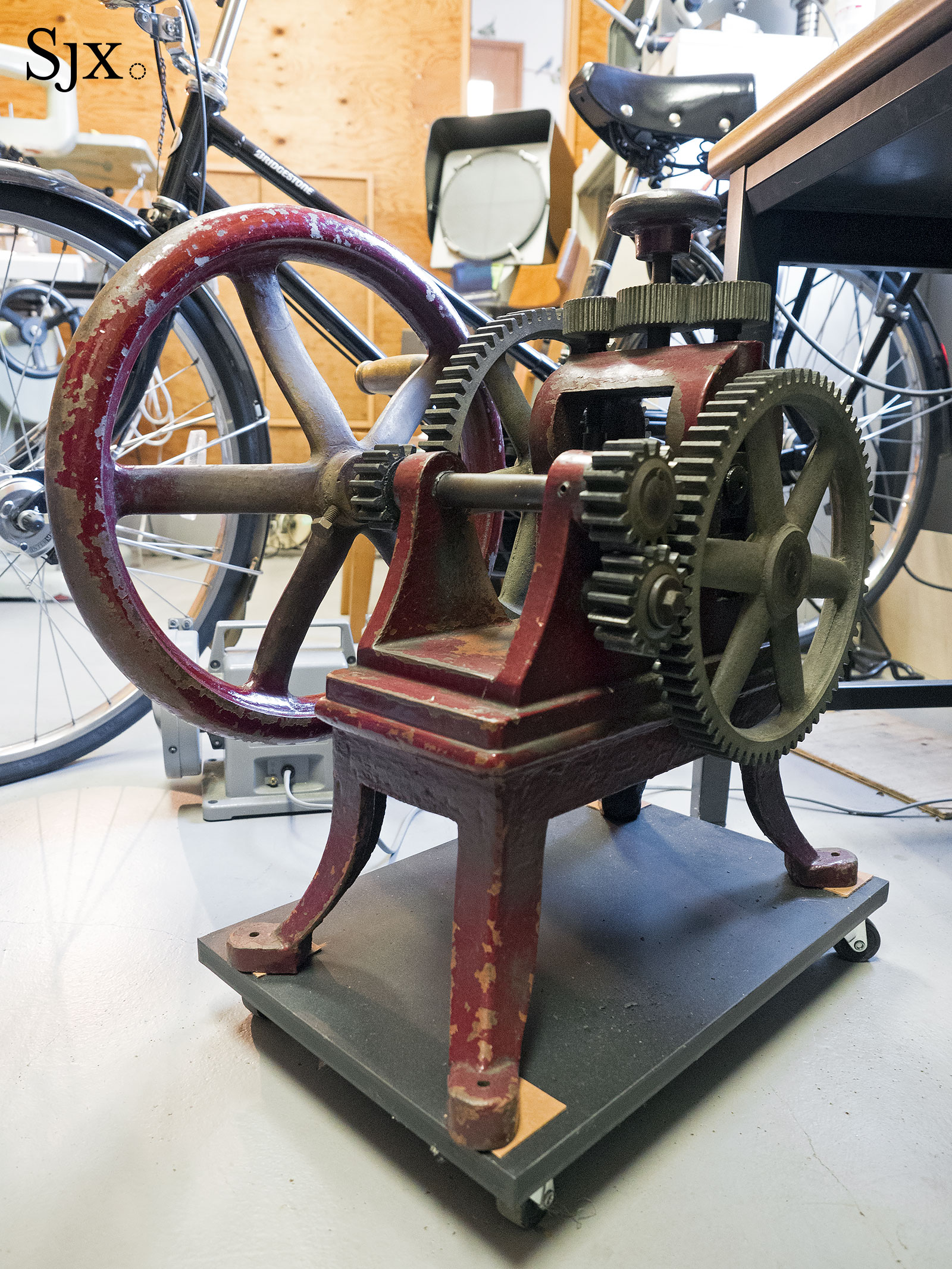

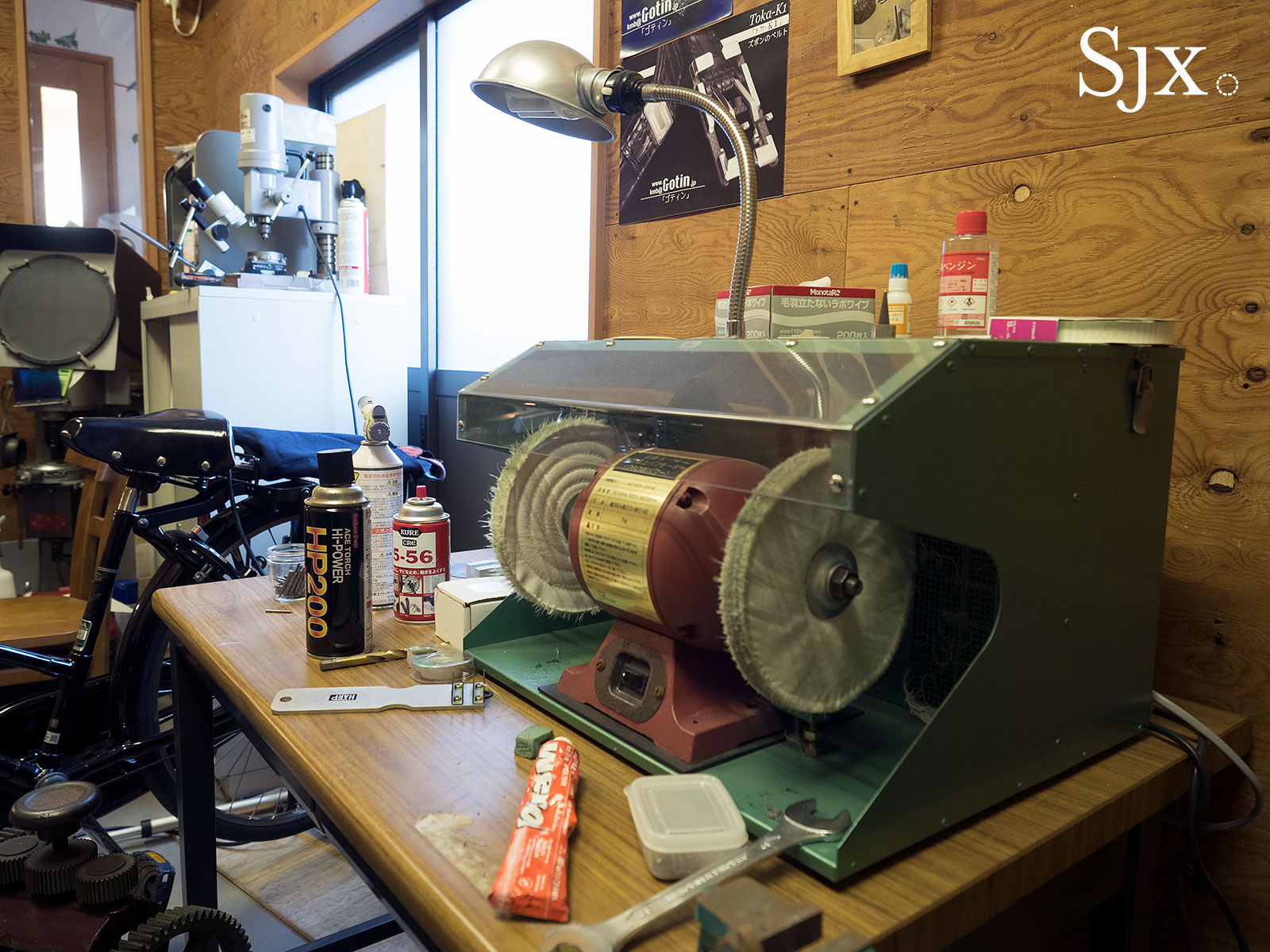

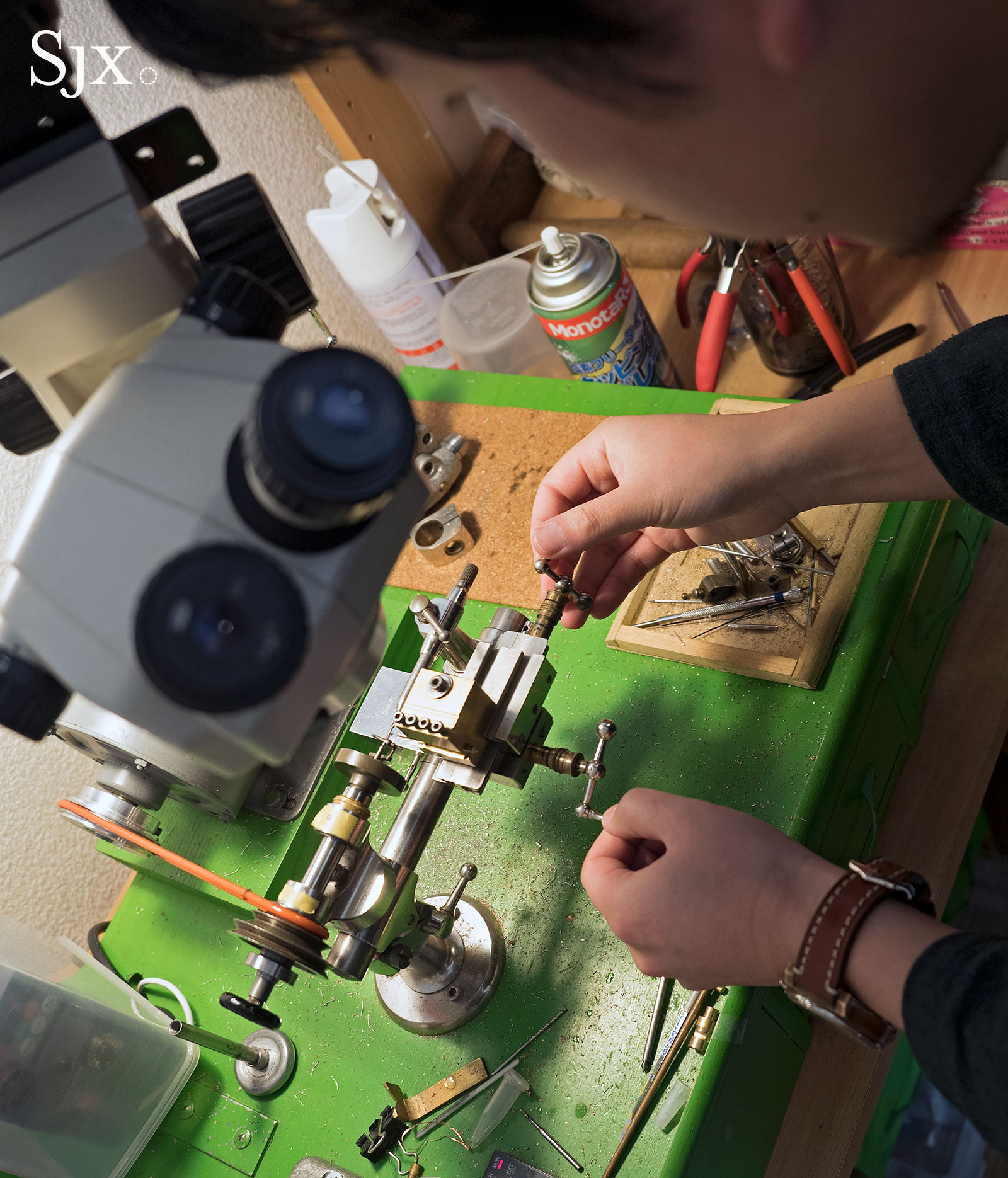

Despite its modest size, Kikuno’s workshop is almost entirely vertically integrated. Kikuno has equipment for turning wheels, bluing and tempering steel, and even a roller for making flattening steel bars to make mokume-gane (literally translating as “woodgrain metal”) dials.

Kikuno wearing the now discontinued Mokume wristwatch

He makes nearly the entire watch himself, even the case, an unusual accomplishment for a one-man operation. In fact, Kikuno’s dedication to crafting components is so uncompromising he even produces his own mokume-gane – hammering, rolling and heating copper, gold and silver to produce a woodgrain gold alloy.

The hairspring, mainspring, jewels, crystal and leather strap are bought from suppliers, primarily Seiko subsidiaries.

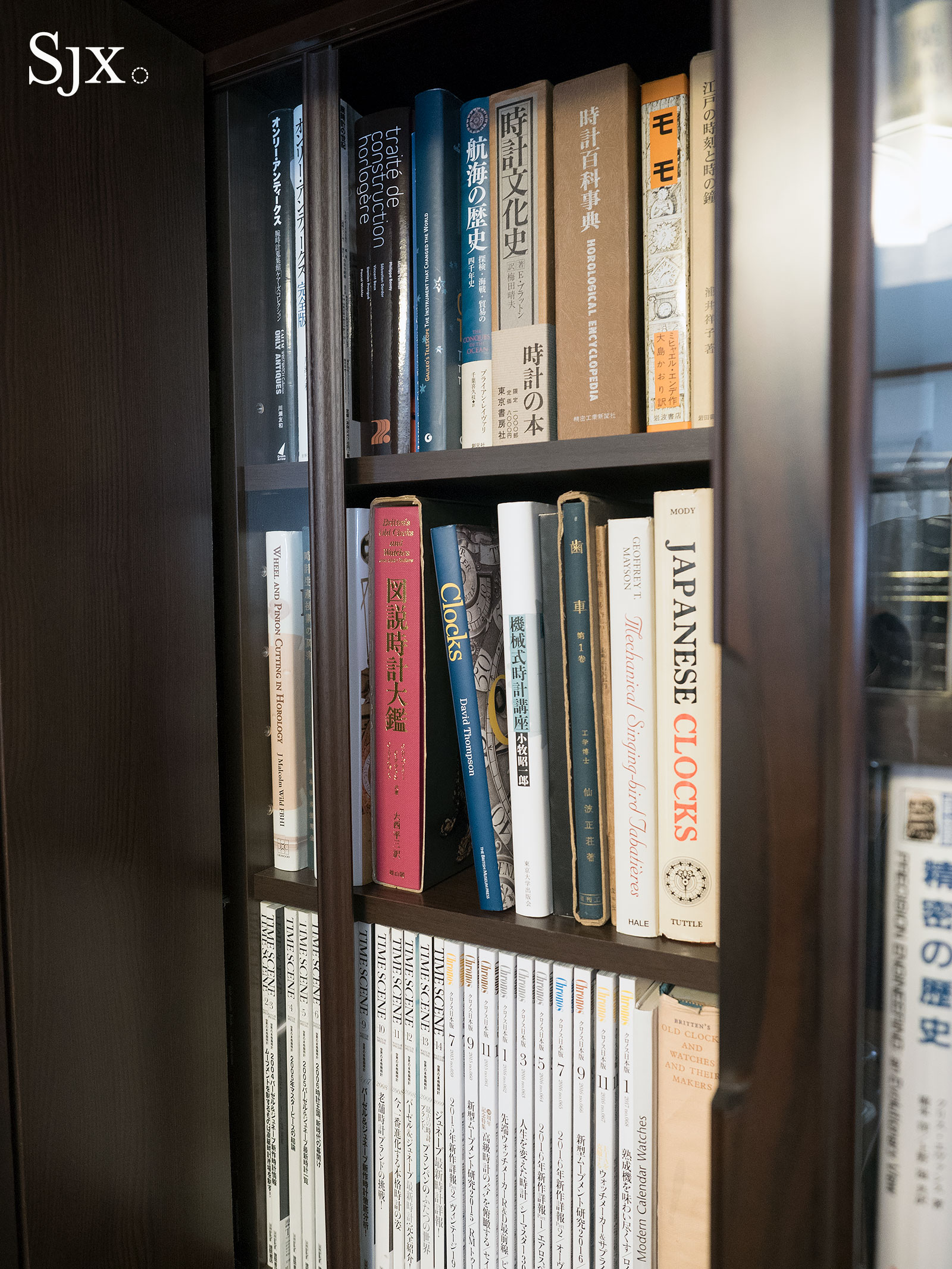

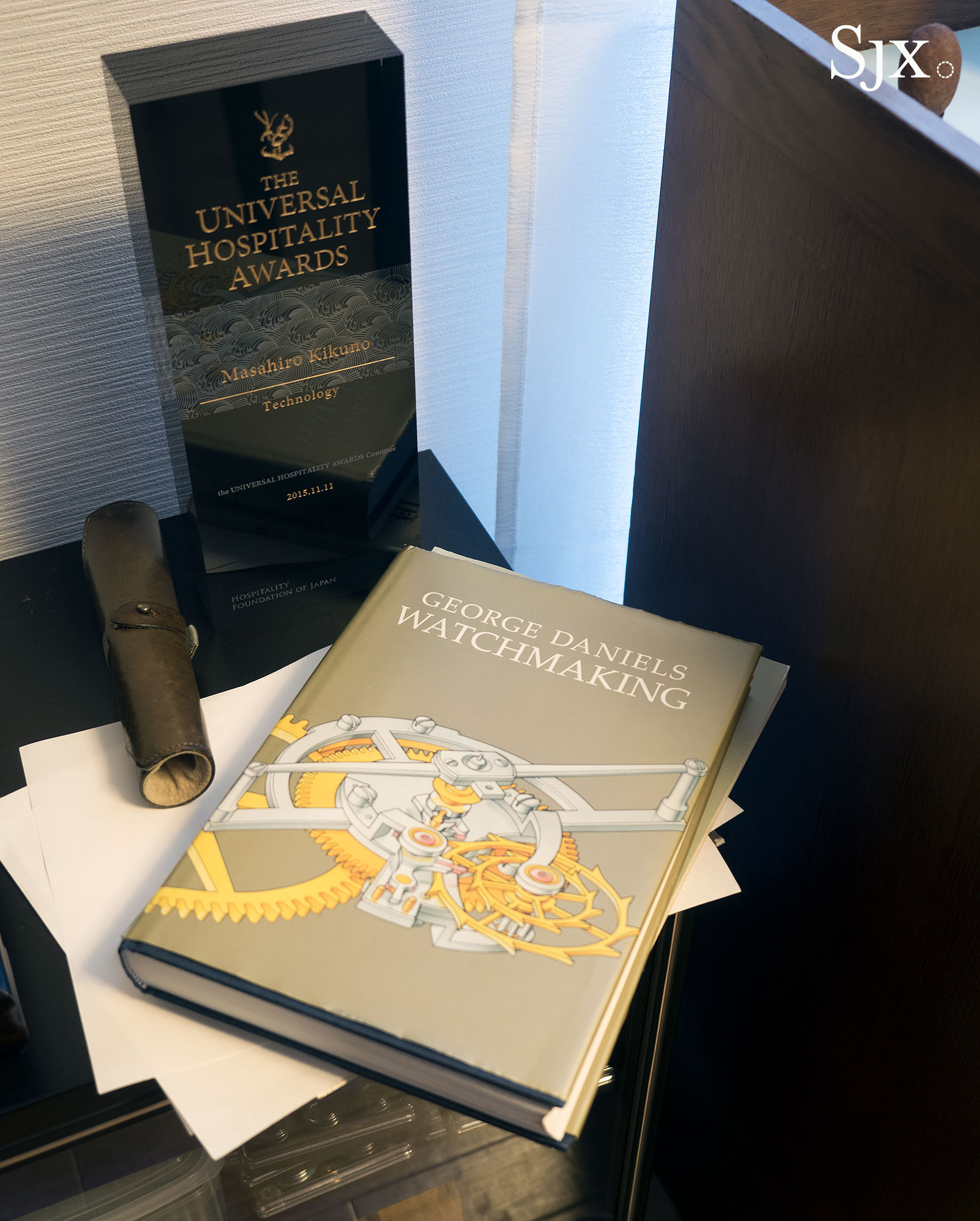

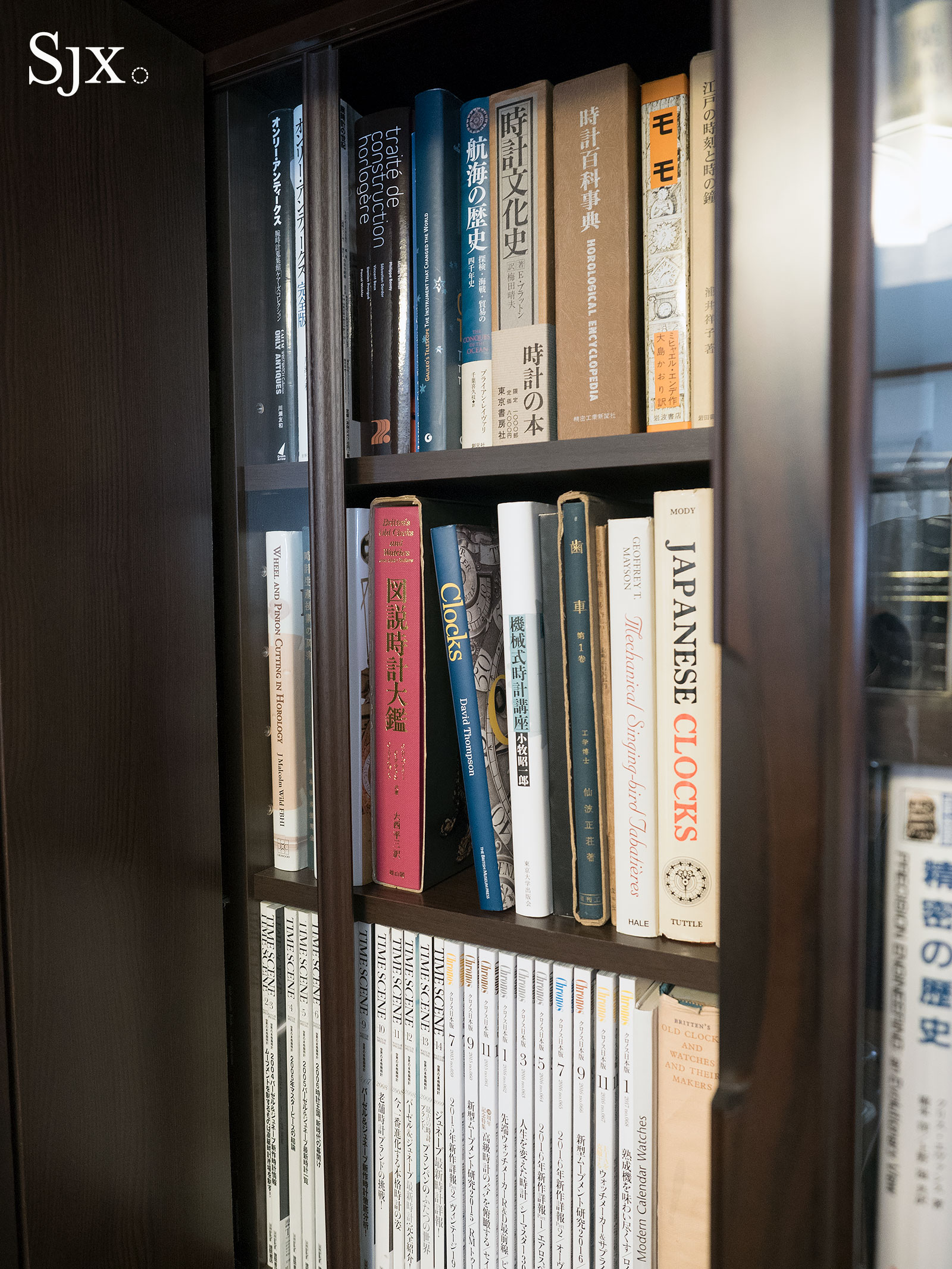

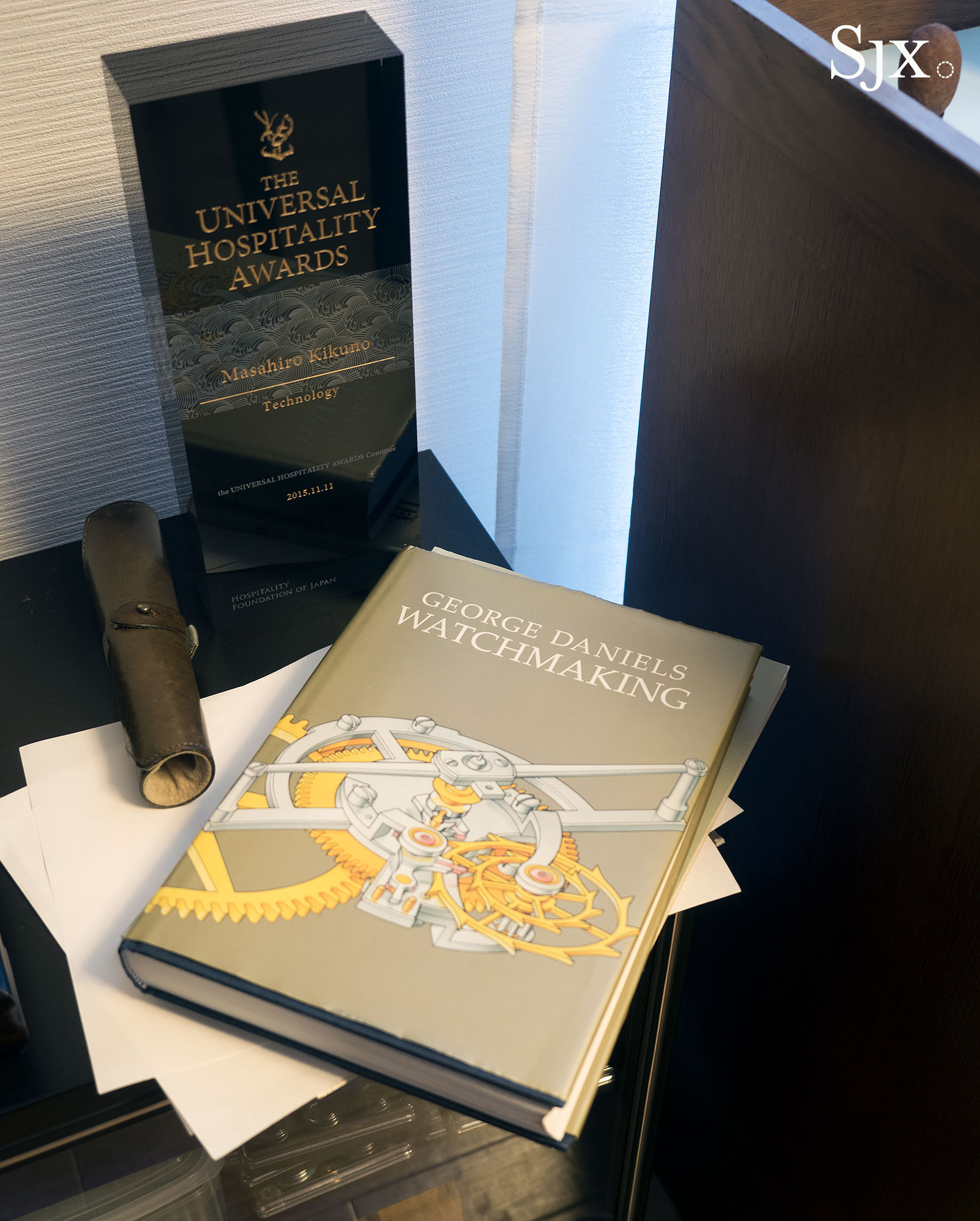

The educated watchmaker’s workshop will inevitably have a well-stocked library

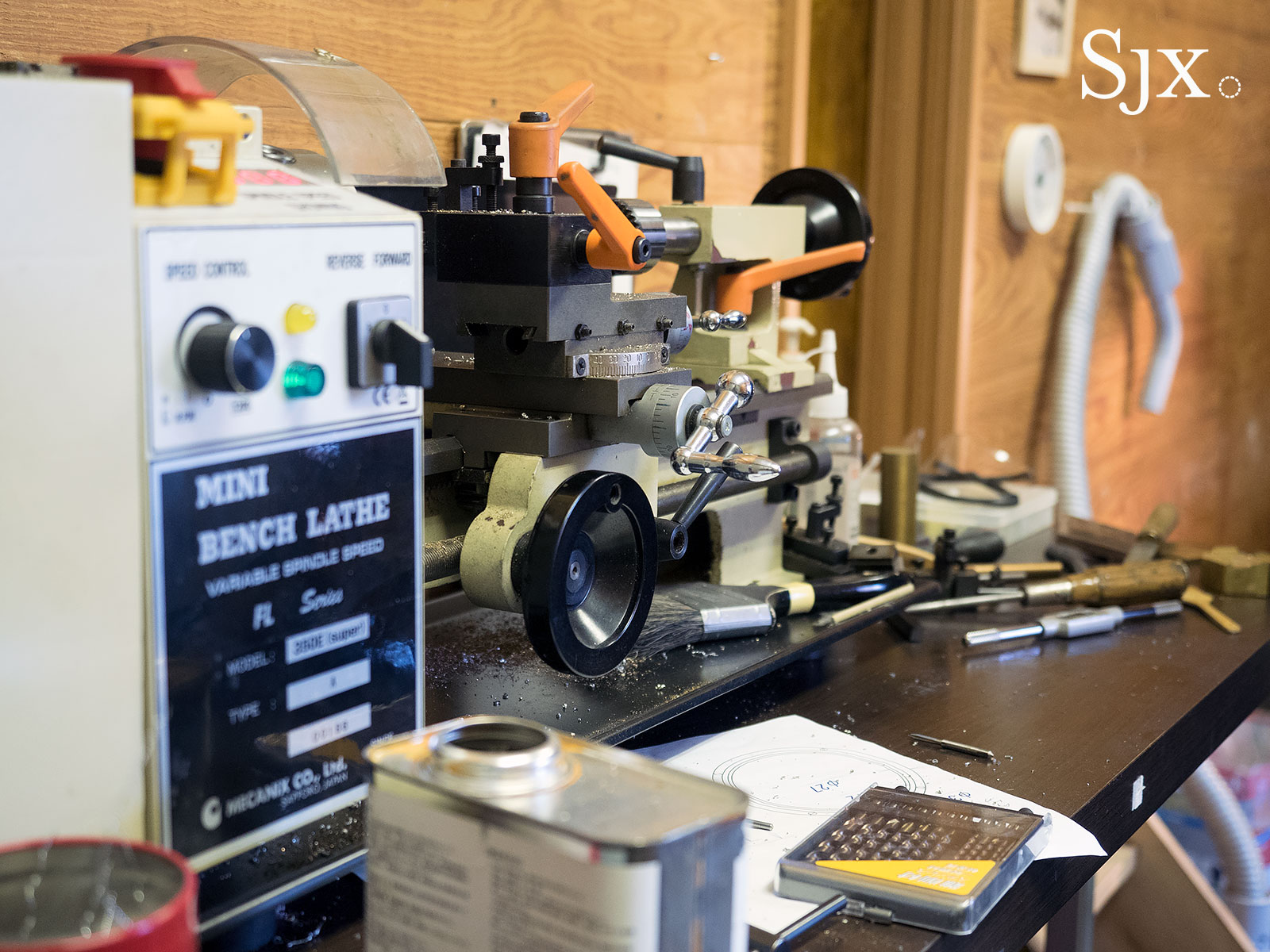

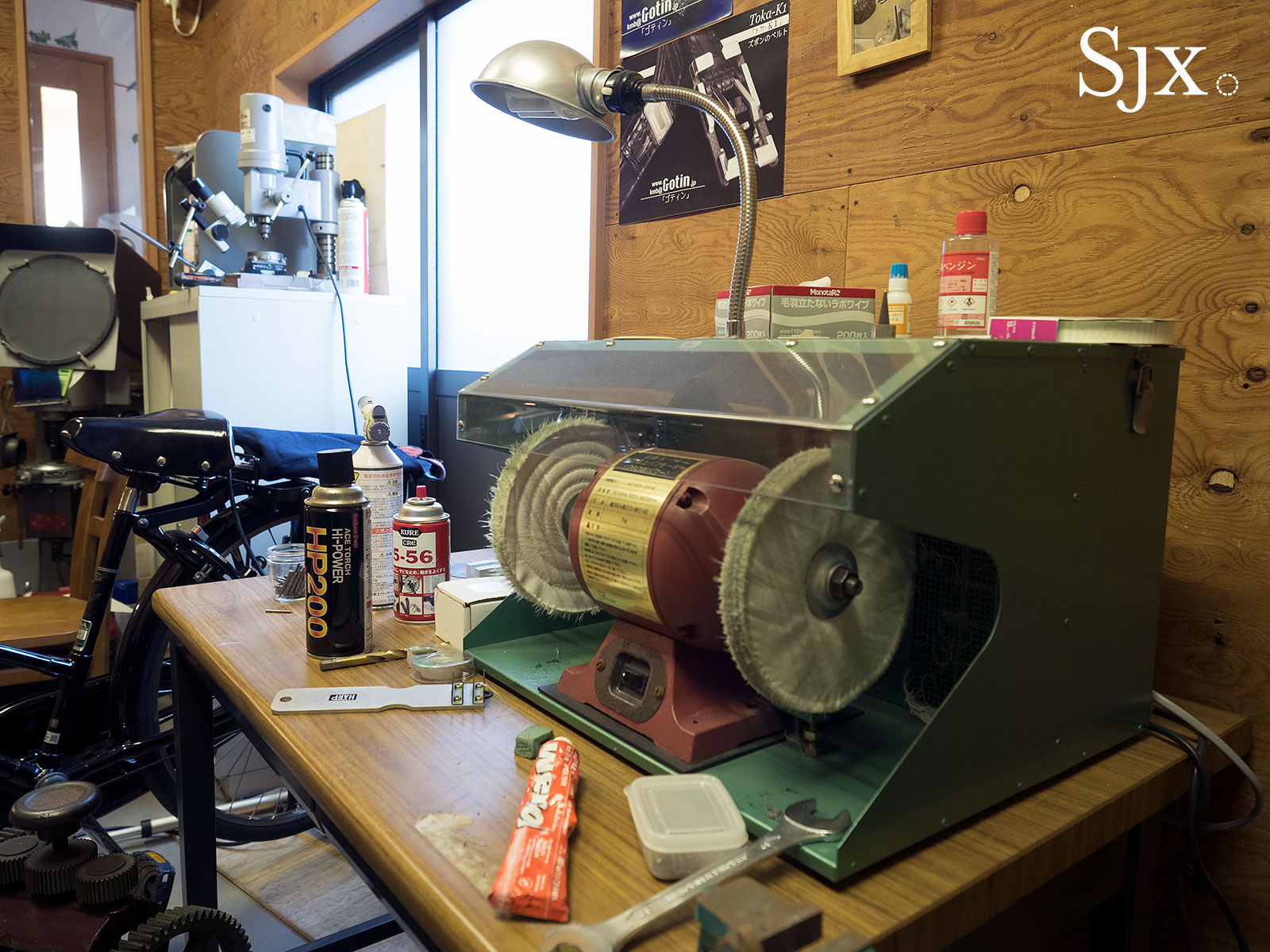

The converted garage

Like the houses, garages in Japan are fairly compact, built to accommodate practically sized cars. Yet Kikuno has managed to equip it with everything necessary. Much of the heavy lifting – fabricating main plates and bridges, polishing, metalworking – is done in the garage.

The roller for flattening mokume-gane bars

A polishing machine

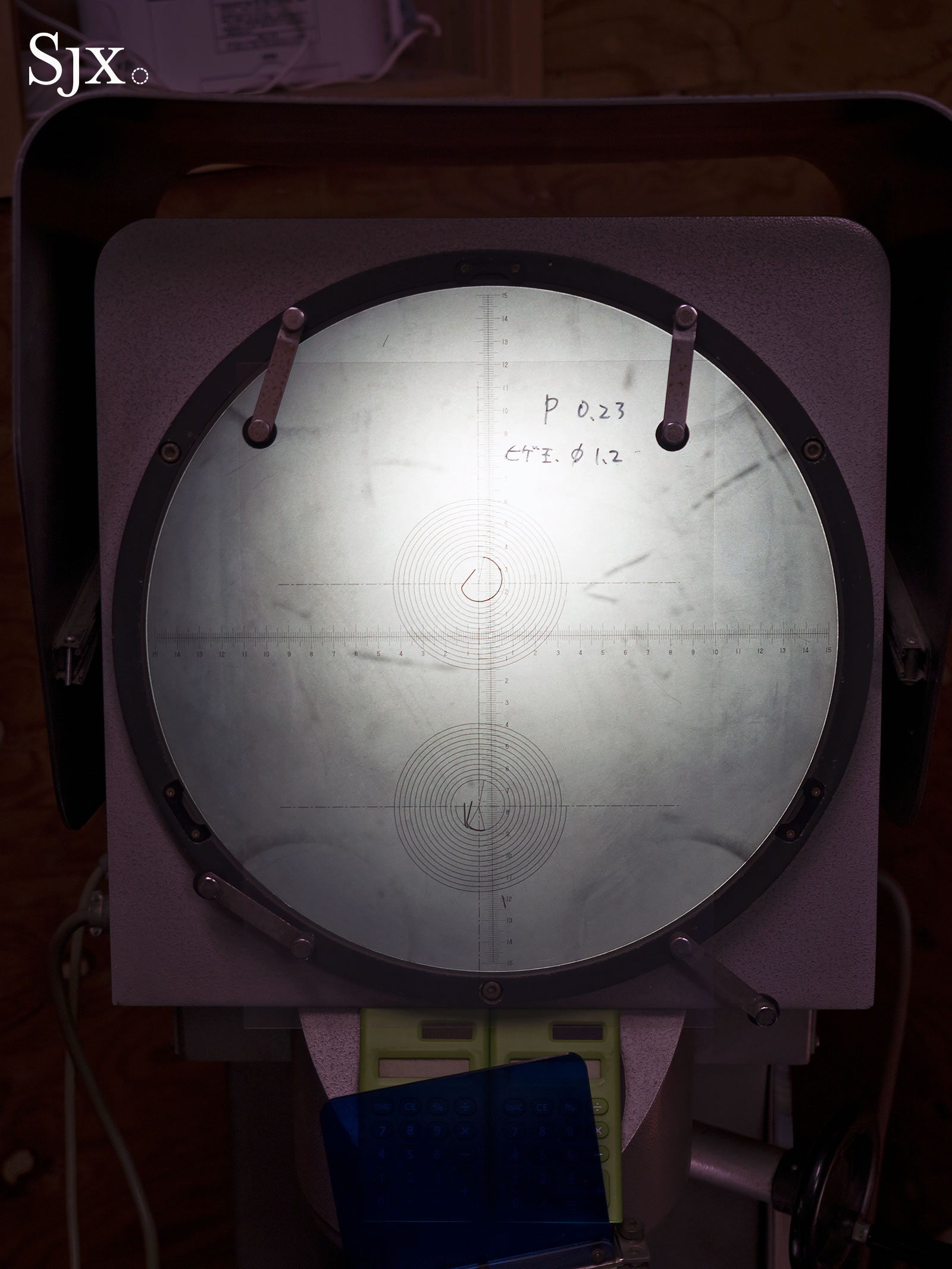

His machine shop also includes an old school milling machine. It’s operated manually: Kikuno traces the hand-drawn plan for the baseplate with a stylus, while the cutter simultaneously mills out the part.

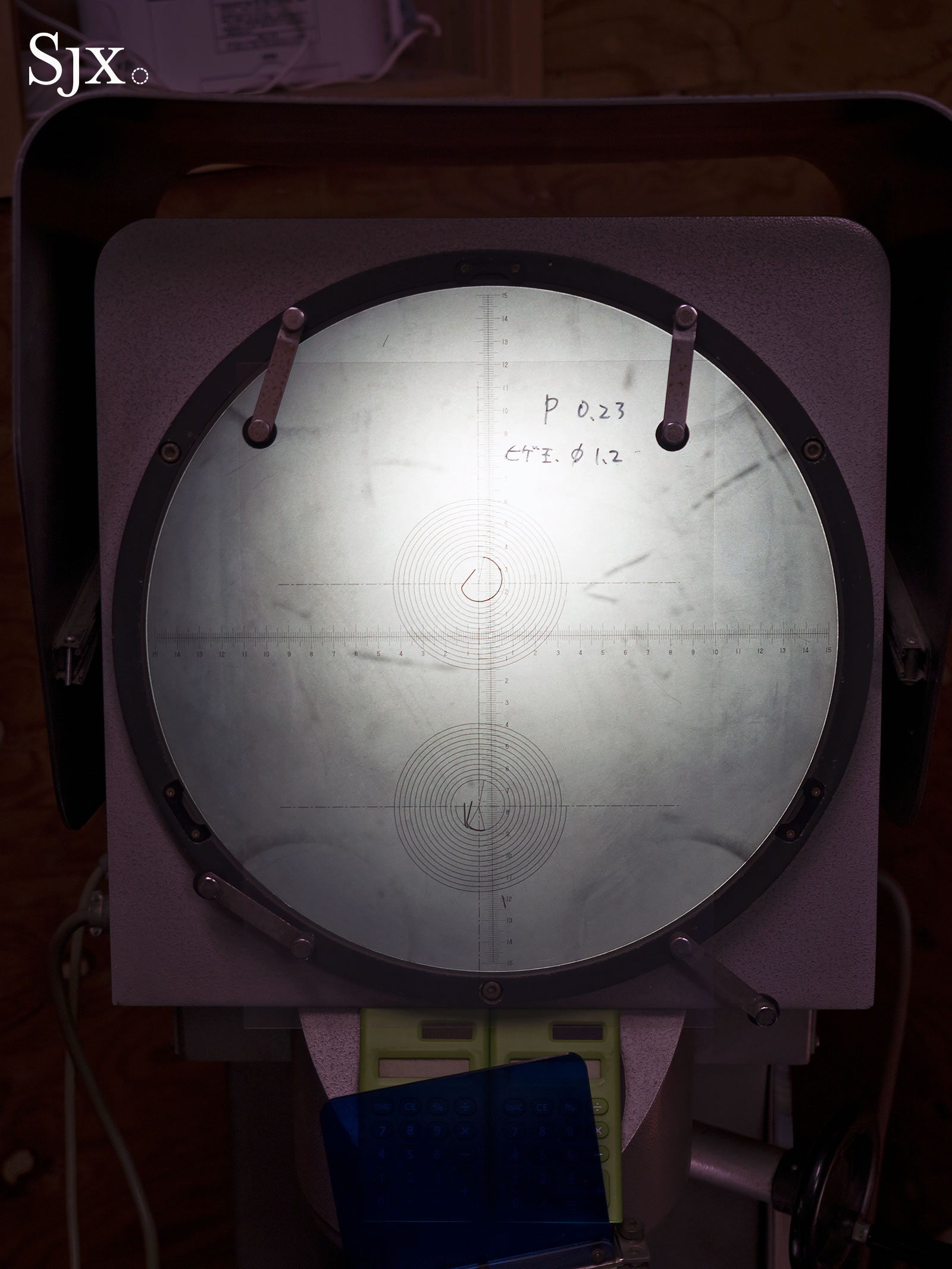

Kikuno also has to do his own quality control to ensure all the parts he produces are up to spec. He does this with an optical comparator, a device that projects a magnified image of a part against an overlay chart.

The genesis of an idea

Kikuno’s path to watchmaking was an unusual one, having been a small arms technician in the Japanese Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) for four years starting at age 18. It was in the military that Kikuno found his calling, when he met a senior officer who was a watch enthusiast.

Kikuno then left the JSDF, enrolling in a four-year course at the Hiko Mizuno College of Jewelry in Shibuya, a Tokyo district better known for its fashion stores. It was there that he produced his first timepiece, a time-only wristwatch with a retrograde display.

His first watch/photo courtesy Masahiro Kikuno

The college, however, taught watch repair, rather than watchmaking, leading Kikuno to embark on a journey of self education. Like many other self-taught independent watchmakers, Kikuno studied the craft primarily via George Daniel’s seminal Watchmaking, which instructs the reader on how to produce a tourbillon. That led Kikuno to build his first tourbillon wristwatch in 2010.

For a spell after graduation Kikuno continued as an instructor at the college, but in 2012 set up shop on his own as an independent watchmaker. A year later he became a member of the AHCI.

Five years on, Kikuno is still in the process of developing a house style, explaining the diverse aesthetic of the watches he has made. The fact that he makes nearly everything himself also means limitations in certain areas, like the shape of the watch case for instance.

Uncompromisingly traditional

Kikuno has built only a handful of watches in the seven years since he started, averaging one watch a year. That’s a consequence of his uncompromising adherence to traditional techniques of production.

In fact, he briefly attempted to produce timepieces without electricity, neither for lighting nor equipment, because it was how it was done in the 19th century. He somewhat sheepishly admits the effort was quickly abandoned due to sheer impracticality.

Tools to blue and temper steel parts

Consequently it is fitting that his signature timepiece is the wadokei wristwatch, the first time a traditional Japanese timekeeper has been produced in wristwatch form.

The wadokei keeps seasonal time – meaning days are longer in summer and shorter in winter – a system of time-telling that was replaced by conventional 24-hour days when Japan modernised after the Meiji Restoration. Kikuno’s wadokei wristwatch is essentially a miniaturised version of the original clocks, but it tells both traditional and modern time.

Kikuno’s personal wadokei worn as a pocket watch

The elaborate, engraved wadokei wristwatch

Not only are the production methods similar, Kikuno also points out that his approach to producing the wadokei is historically correct, for the clocks were typically produced by a single craftsman, rather than a series of contractors as it was in Switzerland during the same period.

The watches

Kikuno’s watches start at approximately ¥5m, about US$45,000, for the Sakubou wristwatch that features a moon phase and a hand-cut, kuro-shibuichi dial. Made of a copper, gold and silver alloy, the dial takes Kikuno two days to complete, first having to cut the floral motif by hand with a tiny saw then treating it to create a matte black finish.

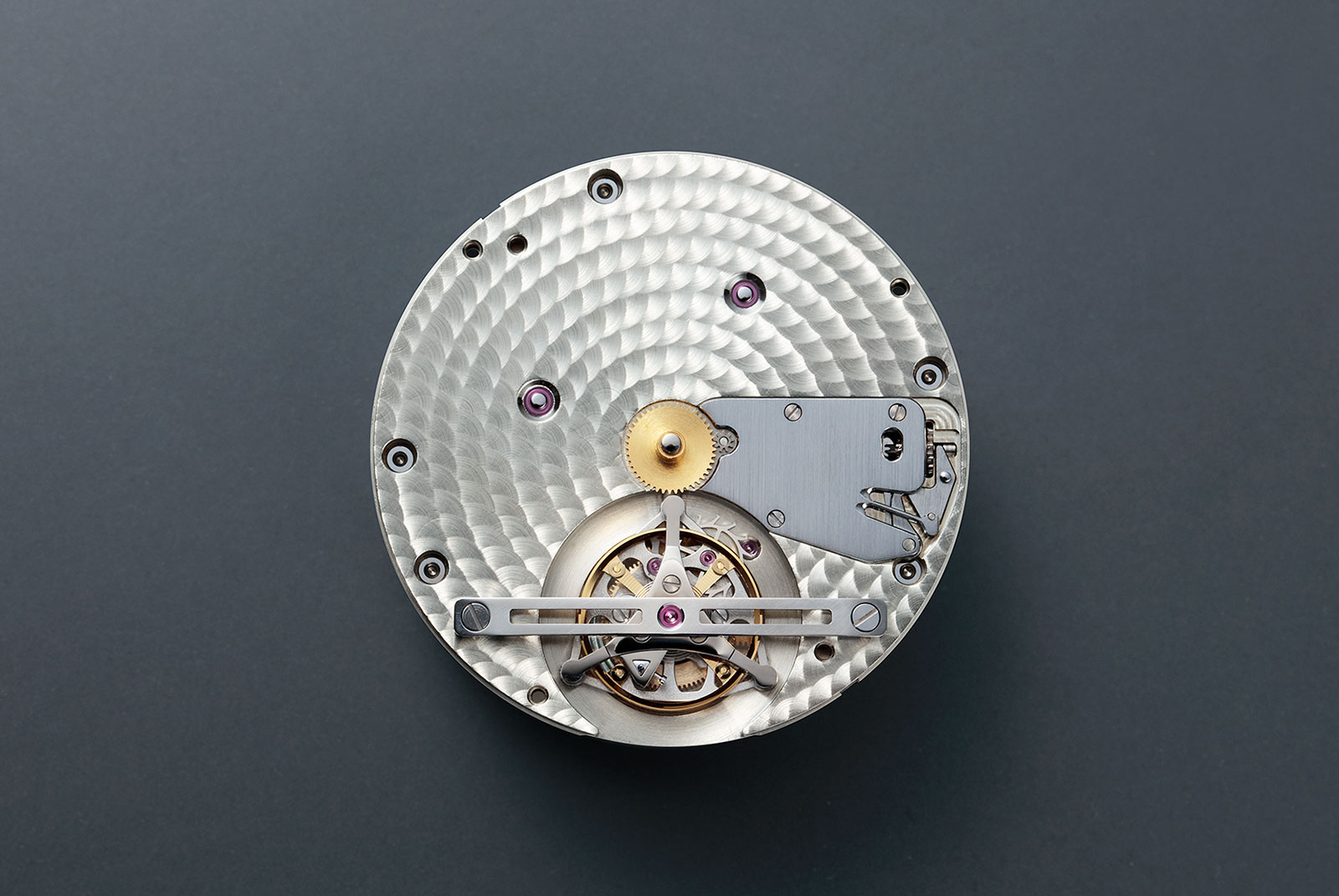

The Sakubou is powered by an in-house movement naturally, one designed and built from scratch by Kikuno. The moon phase display at six o’clock is accurate to a day in 122 years, the standard in modern watchmaking.

While Sakubou is Kikuno’s latest creation, having just been unveiled at Baselworld 2017, his most distinctive wristwatch, however, is undoubtedly the Wadokei wristwatch. This starts at ¥18m (about US$160,000) for the basic version, rising to ¥25m (US$225,000) for the fully engraved model.

The wadokei fully-engraved

His tourbillon, on the other hand, costs approximately ¥10m (US$90,000), indicating how much more complex the wadokei is.

Kikuno also has a handful of prototypes sitting around the workshop, movements he works on when he has the time. Amongst the works in progress is an intriguing, pocket watch sized double balance wheel prototype that is similar to the F.P. Journe Resonance. He does not know if it will ever be turned into a commercially available timepiece.

Masahiro Kikuno’s watches are available direct from the watchmaker, who can be reached via his website.

Back to top.