The Watch Lord Nelson Left Behind

A tragic Victory.

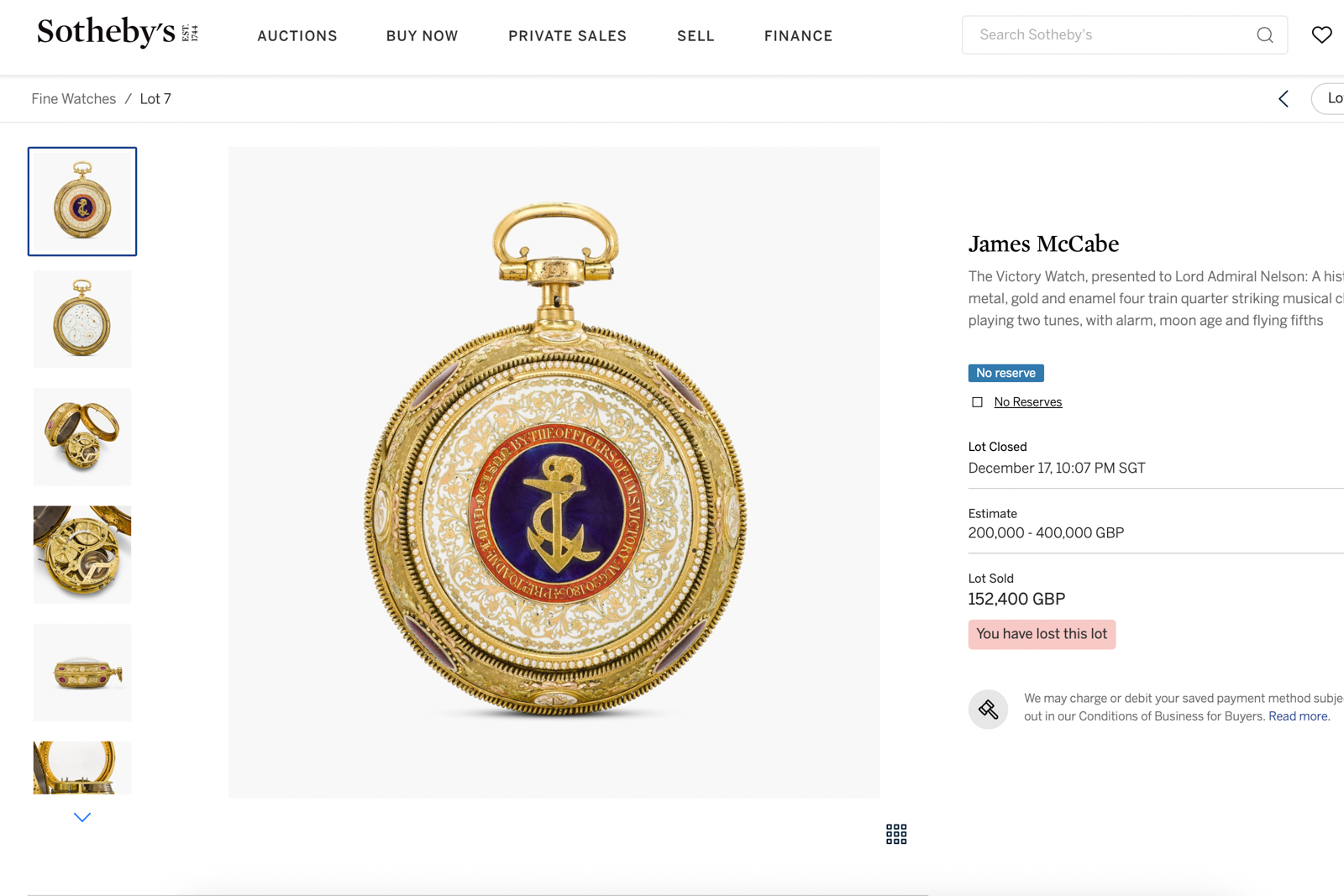

When Sotheby’s closed its Fine Watches online auction in London on December 17, the Victory Watch made by James McCabe and presented to Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson by the officers of HMS Victory sold for £152,400, fees included; below the low estimate. The price was unexpected for an object with an unusually intimate Nelson provenance: a gift from his officers that belongs to Nelson’s last weeks on land, before his victory and death at the Battle of Trafalgar, and to the choice he made to keep the watch at home.

The Victory. Image – Sothebys (Turner, the battle of Trafalgar) Wikipedia

Understanding the Victory

The case bears the presentation inscription, “Pres. to Adml. Lord Nelson By the Officers of HMS Victory Aug 20 1805”. That date sits in the hinge of his final summer. Nelson had returned to England after a long, grinding command, and the country treated him as a national hero.

He slipped away to Merton Place in Surrey to live, briefly, in the domestic scene he valued: a house shaped around his wife, Emma Hamilton, their daughter Horatia, and the familiar ritual of guests, dinners, and the small civilities of being ashore. The officers who commissioned the watch gave it to the man they knew at sea, and to the man they sensed existed elsewhere; the man who also wanted beauty, music, and calm within reach.

Within a fortnight the strategic situation tightened. News that the French and Spanish fleets had combined at Cádiz brought recall. On September 14, 1805, Nelson left Merton before dawn, returned to Portsmouth, set sail on HMS Victory within hours. He would never return.

View of the case. Image – Sothebys (Turner, the battle of Trafalgar) Wikipedia

First sold in 2005 by Sotheby’s as part of the Matcham Collection, the McCabe watch does not appear in the inventories of Nelson’s possessions after his death, a point Sotheby’s itself has long used to argue that it remained at home. The 2005 press coverage of the Matcham Collection sale made the same observation, and it remains the cleanest clue we have. The absence makes practical sense once you understand what this object is. It presents itself as a watch, yet its size and purpose pull it into a different category: a small domestic instrument, timekeeper, musical mechanism, and ceremonial object.

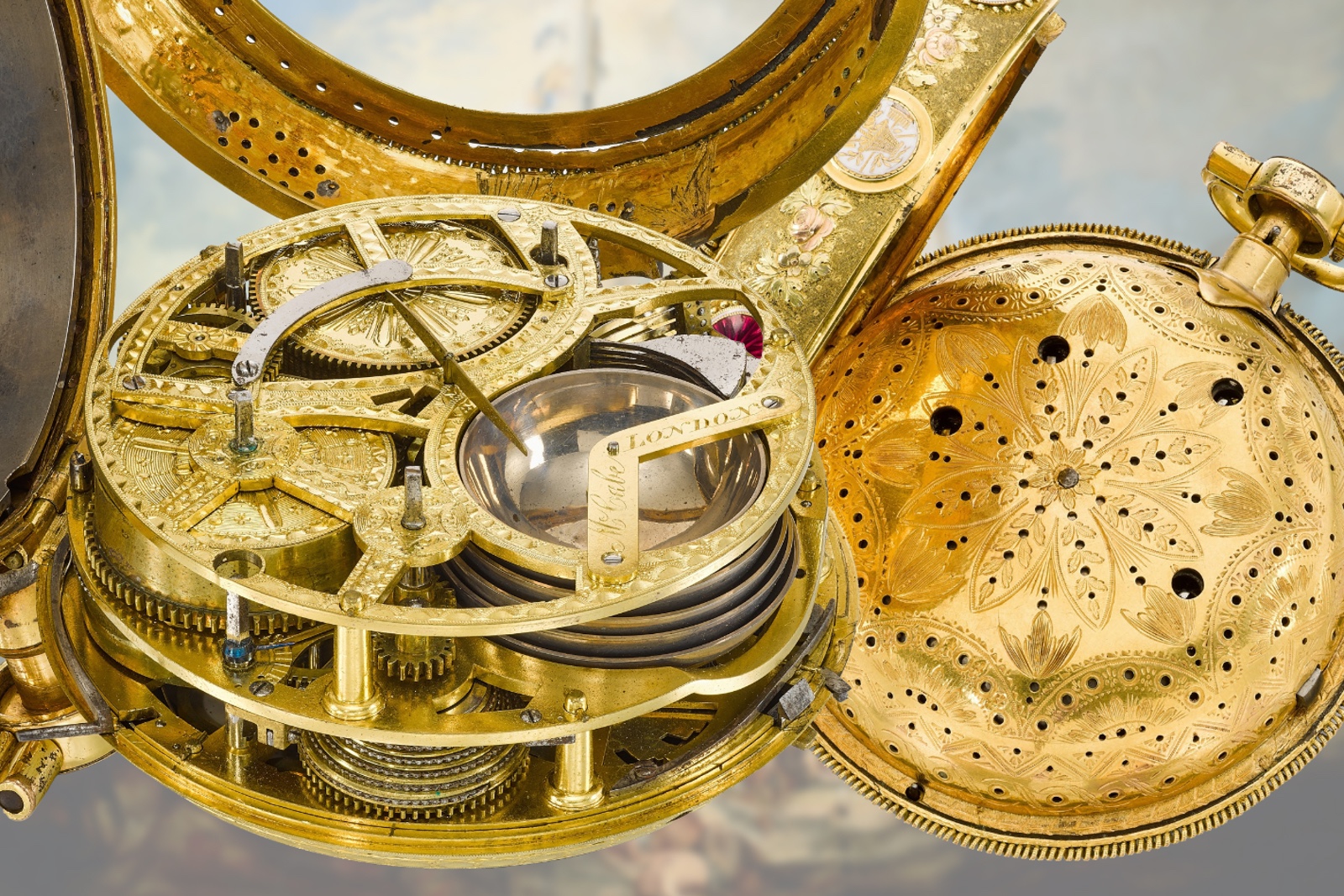

At 120 mm across, close to 5 in, it was never built for the pocket of an officer working the quarterdeck. Rather, it is almost a portable clock. Inside is a four-train, two-tier movement with a fusee and chain and a cylinder escapement for the going train, with separate trains for striking, alarm, and music. The musical work sits on a pinned barrel that drives a dense linkage, eleven levers, 11 hammers, and six bells, plus a larger seventh bell mounted within the case back to deliver quarter striking. The sound would have been bright, insistent, and designed to be heard in a room with people talking. It belongs to the refined world of Merton, not the inferno off Cape Trafalgar.

View of the movement. Image – Sothebys (Turner, the battle of Trafalgar) Wikipedia

The dial states the same purpose in enamel. Alongside hours and minutes, it carries subsidiary indications that turn the face into a compact theatre: seconds, alarm, lunar age, and a central fifths-of-a-second display, with a tune selection arc arranged near six o’clock. This layout makes the point that the watch was conceived to entertain, to demonstrate mechanical abundance, and to reward close attention.

The case leans into that language of abundance. Both bezels are set with half pearls and edged with rope-twist decoration. The sides carry enamel panels alternating with trophies of music and war in three-colour gold. The back centres on a gold anchor-and-rope motif on blue enamel, encircled by the presentation inscription set against translucent red flinqué enamel. It is patriotic, personal, and proudly metropolitan, the sort of luxury object London could produce at the height of its confidence in craft.

Meeting its maker

James McCabe was a sensible choice for such a commission. By 1805 he was established near the Royal Exchange, operating in the commercial heart of the city and trading on a name associated with technical competence and a polished finish. He was Irish-born, London-based from the 1770s, and linked to the Clockmakers’ Company as an Honorary Freeman from 1781. The family business outlived him, and the McCabe signature became part of a longer nineteenth-century story, though the Victory watch sits firmly in the early nineteenth-century moment when English work still expected to lead the field in complexity and execution.

View of the movement. Image – Sothebys (Turner, the battle of Trafalgar) Wikipedia

If you place the watch back into Nelson’s September, the decision becomes readable. When he returned to sea, he had no reason to carry a large musical showpiece. A simpler personal watch, the kind a commander could consult without fuss, suited active service. The McCabe belonged to the life he had just resumed at home, and to the life to which he certainly hoped to return.

Leaving it at Merton protected it from salt, shock, and loss, and it preserved the gift in the setting where it made sense. It also carries an emotional implication that is hard to avoid. The watch marks the domestic interval as something real enough to deserve its own object, a token that expected future evenings, future dinners, and future time.

Then and now

This post-sale moment invites comparison with the watch’s previous appearance at auction, since that sale fixed the contemporary valuation of the object. On October 5, 2005, during Sotheby’s London sale that included items associated with Nelson’s sister, Catherine “Kitty” Matcham, the watch sold for £400,000, almost 10% of the whole auction’s tally of £4.65 million. It was widely reported at the time as the most expensive Nelson relic sold at auction, and it outperformed several headline lots, including the admiral’s undershirt, which failed to sell.

Movement and case view. Image – Sothebys (Turner, the battle of Trafalgar) Wikipedia

The 2025 result of £152,400, fees included, places the watch in a different register. Part of that is time, part of it is category. The piece sits across two constituencies, Nelson material culture and serious English musical watch collecting. Either world can sustain a strong price on its own terms, story on one side, horology on the other.

Here they meet, and the watch asks bidders to carry both ideas at once, since its pull comes from the overlap. In an online sale, that overlap can be harder to price with confidence. Even so, the watch remains what it has always been, substantial English work, and a relic that fixes Nelson to a specific address and a specific mood, the brief calm before he returned to duty.

There is another reason the watch keeps returning to the centre of Nelson’s material culture, it refuses to join the battle narrative. Many Trafalgar objects draw their force from proximity, the deck, the shock, the aftermath. The McCabe draws its force from distance. It stayed in a quiet room while the outcome of Europe’s naval war was decided off Cape Trafalgar. It sits beside the legend, yet it points elsewhere, to the private machinery of a life cut short.

Reflections on the result

Given the remarkable history of the watch, the hammer price below the low estimate left bidders surprised, perhaps explaining the frantic climb in the final moments – with 12 minutes remaining, the price had yet to break six figures.

We managed to reach one of the underbidders on the watch, who explained his rationale. “The historical importance of this watch is undeniable, but it is far from what I normally collect so I did not pursue it,” he says, “In hindsight, I slightly regret it because it might just be the most historically significant watch sold in 2025 – and it sold for a song!”

According to the underbidder, “The importance of this watch is so profound one can almost hear Rule Brittania playing when you look at it.”

And we also managed to reach the winner, who fortunately clearly understands the significance of his own ‘victory’. “By coincidence, several Nelson watches appeared at auction this season. Among them, this is the most compelling to me mechanically — defined by its high level of complication and a rare musical complication played on a nest of bells,” he explains, “A watch not only to own, but to display, study, and use as a tool to educate the public.”

Back to top.