In-Depth: The Unique and Magical Oval Tourbillon Watch by Derek Pratt

A hand-made masterpiece.

I first met Derek Pratt (1938-2009) at a sale held by Ineichen, a Zürich-based auction house, in 1975. He was in the company of Peter Baumberger (1939-2010), an antique watch dealer and trained watchmaker that took over long-dormant Danish brand Urban Jürgensen & Sonner in 1981 .

A contemporary and friend of George Daniels, Derek was a talented English watchmaker who restored many of Baumberger’s outstanding historical pocket watches.

Amongst them was then the most complicated Vacheron Constantin ever, the grand complication N°402833 made for King Fuad of Egypt in 1929, which Baumberger bought at auction – the watch was lot 202 at the October 7, 1979 sale at Galerie d’Horlogerie Ancienne (the business founded by Osvaldo Patrizzi that would later become Antiquorum). Baumberger would have trusted no one else other than Derek to restore that watch.

In the following years, I visited Derek’s workshop several times with Peter, often in the company of illustrious watch collectors and enthusiasts, all fascinated by Derek’s knowledge of traditional watchmaking and his beautifully equipped workshop.

Not long after, Peter recruited Derek to be consultant and technical director at Urban Jürgensen. As such, he was responsible for the company’s greatest technical achievements in pocket watches, which was the leading genre in watch collecting at the time.

Derek at work

According to Urban Jürgensen records and my personal archive, Derek completed around 34 watches for the company, all pocket watches.

Twenty of them possess a perpetual calendar and either a minute repeater or split-seconds chronograph – or all three complications combined. Around twelve pocket watches were equipped with a tourbillon, some with a remontoire constant-force mechanism. And there exists one perpetual calendar, minute repeater pocket watch with equation of time.

Derek’s output included two unique pieces: a pocket watch with tourbillon, jumping seconds, and a remontoire within the tourbillon carriage, George Daniels’ double-wheel escapement, and then what is arguably the greatest watch Derek ever created, the Oval pocket watch featuring a flying tourbillon with remontoire and detent escapement.

Peter Baumberger with the Oval pocket watch

The landmark masterpiece

Derek’s most famous and iconic pocket watch, the Oval pocket watch illustrates perfectly the breadth and depth of his skills and knowledge. Derek was so proud of his achievement that he made it his logo on his business card.

When considering this unique piece, it is essential to remember that Derek built this extremely complex watch from scratch – by hand. I insist on the term “handmade” to describe the process of manufacturing the Oval watch and its components.

The entire timepiece began with raw materials – essentially sheets and rods off brass, steel, and gold – that were then worked with purely manual techniques, with manually-operated tools, including milling machines with non-automatic controls. Today, even fine, complicated watches by famous independent watchmakers are largely produced by CNC machines that are automated.

Derek’s business card where he proudly presented himself and his skills with a sketch of his oval masterpiece

Derek explained the genesis of the Oval watch in an article on historical oval pocket watches that he penned in the issue of Horological Journal published in April 1993: “As a child I had been fascinated by oval tins. My own interest in oval watches stems right back to those examples, but on seeing the oval Breguet N°1682/4761 [formerly in the collection of the famous pianist Arthur Rubinstein] in the little book by Claude Breguet, A. L. Breguet, Horloger, I felt positively inspired and resolved to make an oval watch myself… The watch was mostly realized as an homage to some of the most preeminent watchmakers of all time, like Abraham-Louis Breguet, John Arnold, and Professor Alfred Helwig.”

Pratt’s guiding principle in conceiving the Oval watch was an aesthetic that would be reflected in the tidiness, symmetry and visibility of the movement and dial, and in the challenge and difficulty of making a case and glass which were not round.

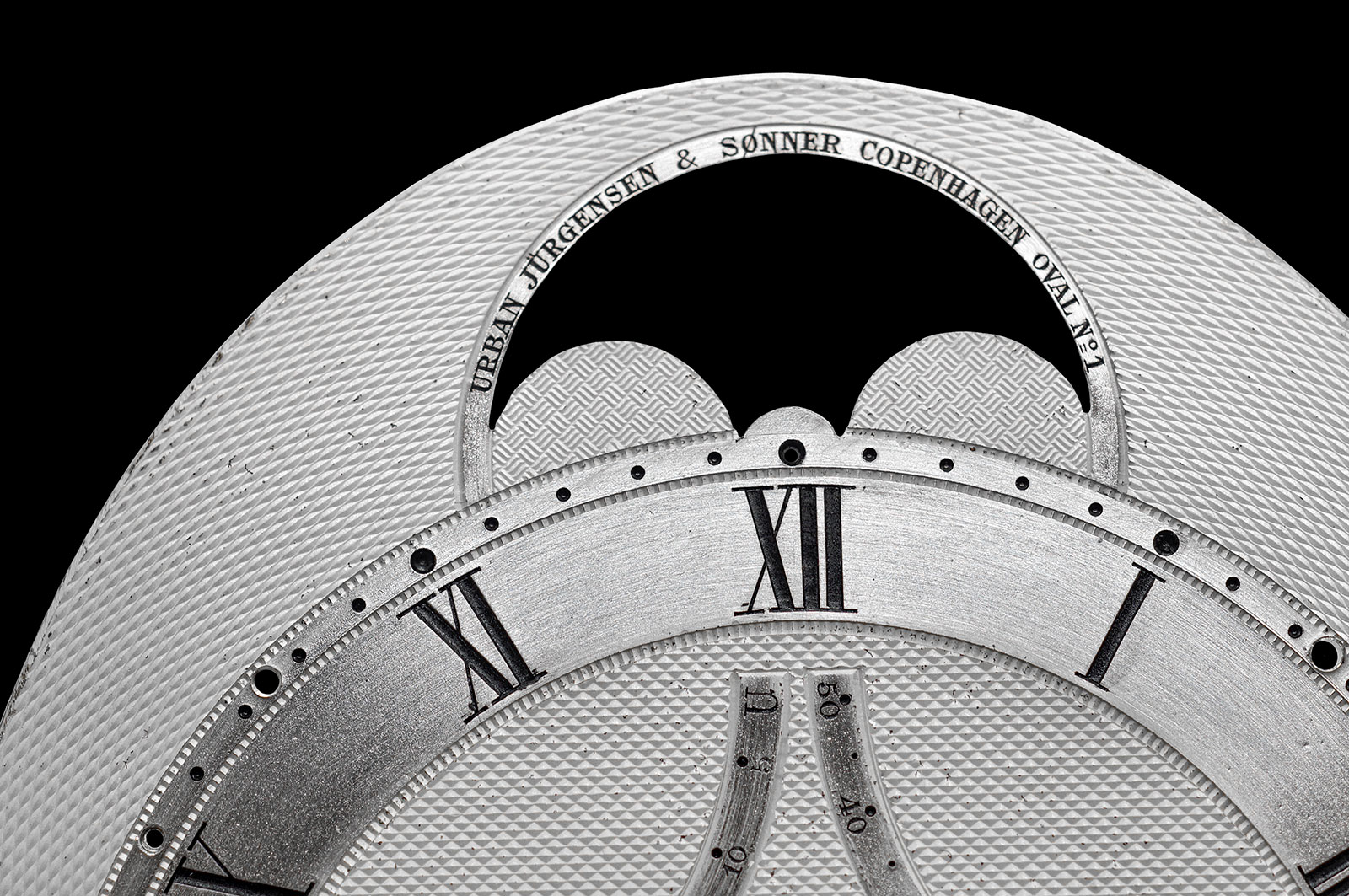

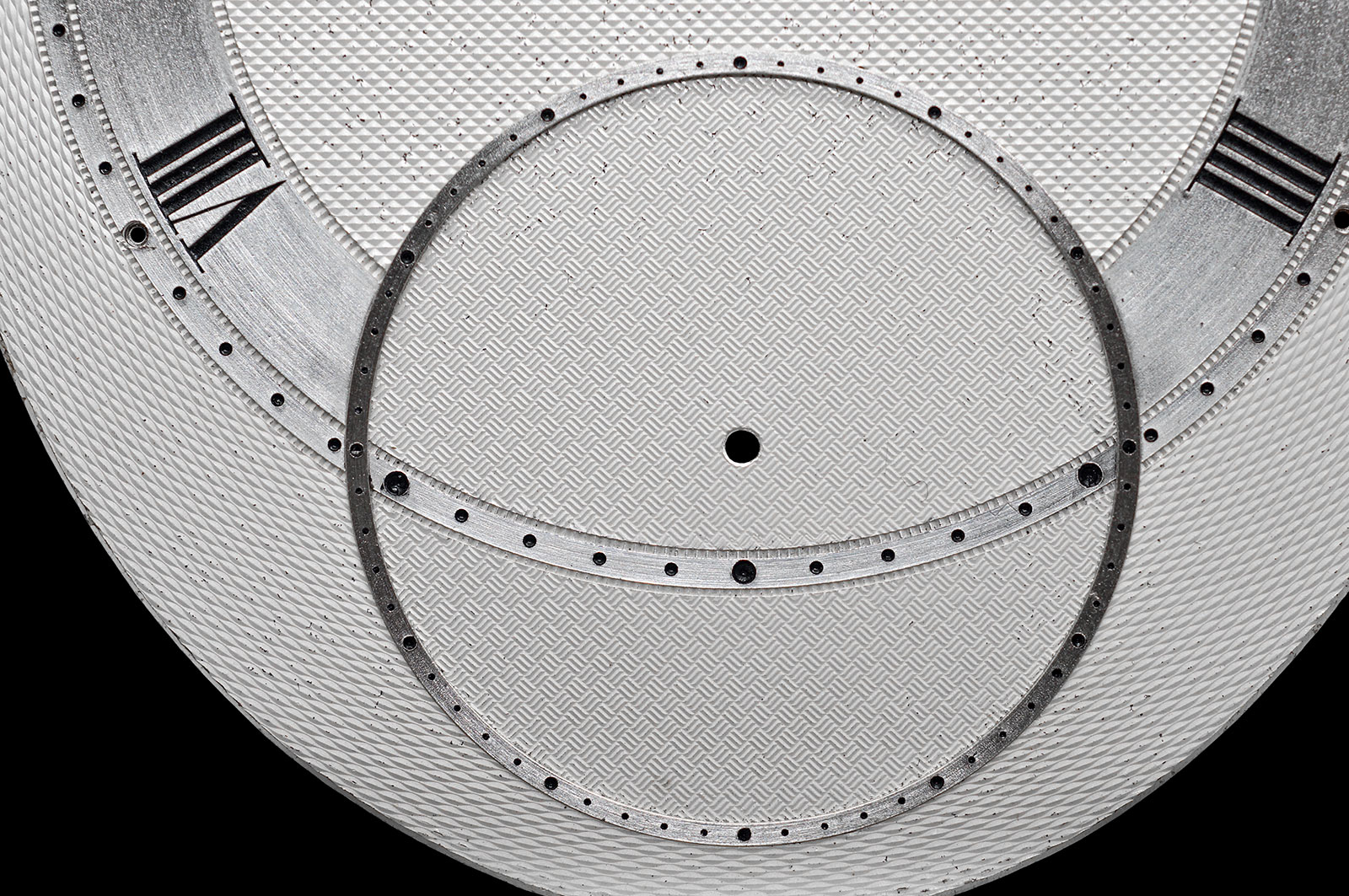

The iconic Urban Jürgensen Oval watch No. 1, a masterpiece by Derek Pratt that was inspired by the proportions widely used by Abraham-Louis Breguet. Note the harmony of the hand-made, engine-turned dial, where the time is indicated by the rounded, solid-gold Breguet hour and minute hands, with the jumping seconds in an elegant sub-dial ring located in the ellipses’ lower focal point at six o’clock. The moon phase is indicated in an aperture in the uppermost section. Twin hands located between the 7th and 8th as well as 52nd and 53rd minute indices show the temperature and state of wind on symmetrical, fan-shaped scales.

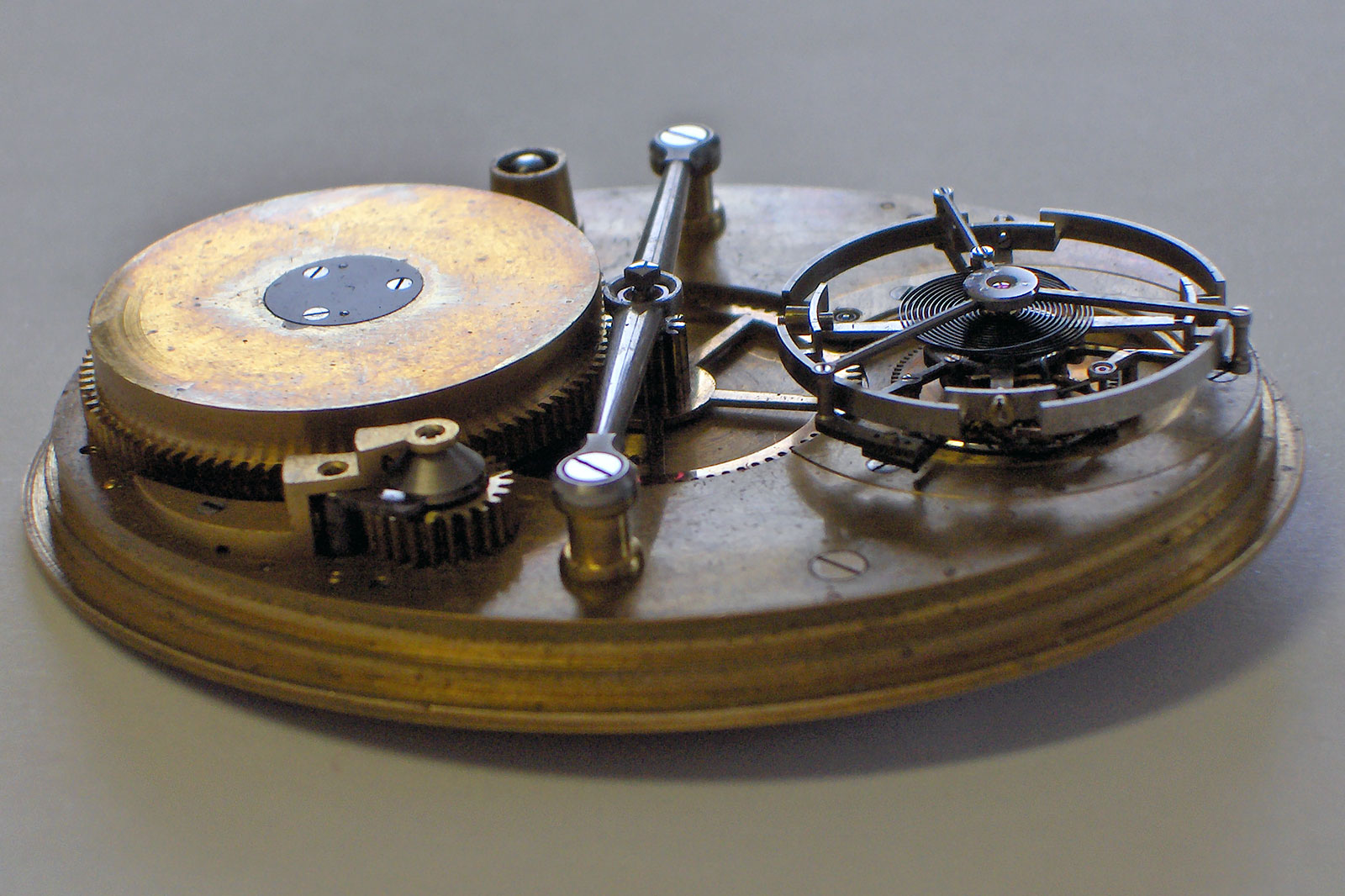

Undoubtfully, an oval design creates symmetry between the large flying barrel on one end and the flying tourbillon cage on the other, as their respective centres coincide with the foci of the axes of the ellipse. The oval shape also allows the dial to be very harmonious and permits to create a large second scale, which in a round watch would be much clunkier.

Finally, the oval shape matches the palm of one’s hand perfectly so that it is a great pleasure to hold the watch whilst admiring all the countless and perfectly finished details.

In his notes, Derek stated that the watch was made between 1982 and 2005, or 23 years – it took half of his horological career to complete. Although unfinished in 1993, the Oval watch was first exhibited at the Basel Fair of that year. Since its creation, the magic of Derek’s Oval watch has never stopped attracting the interest and admiration of watch connoisseurs.

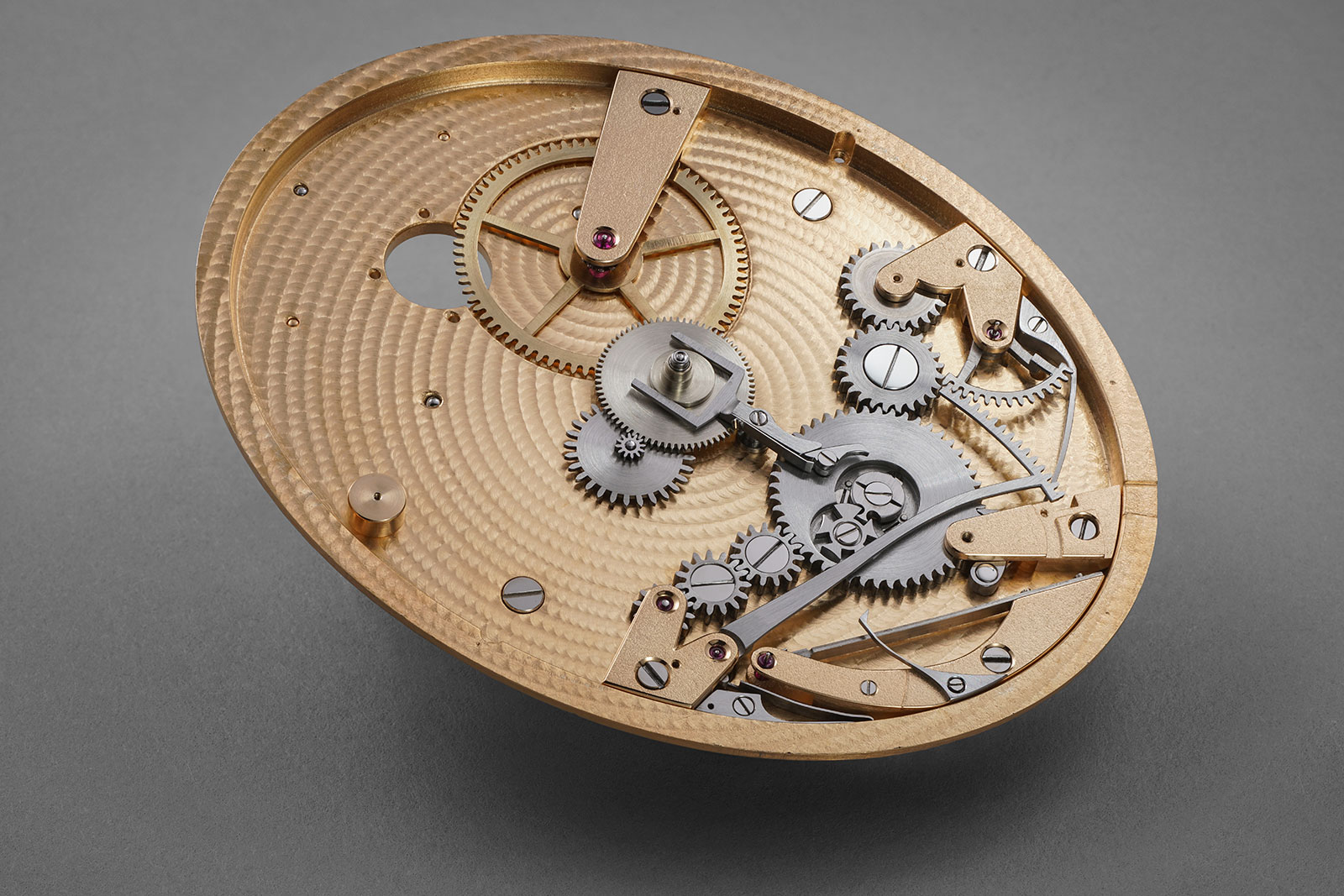

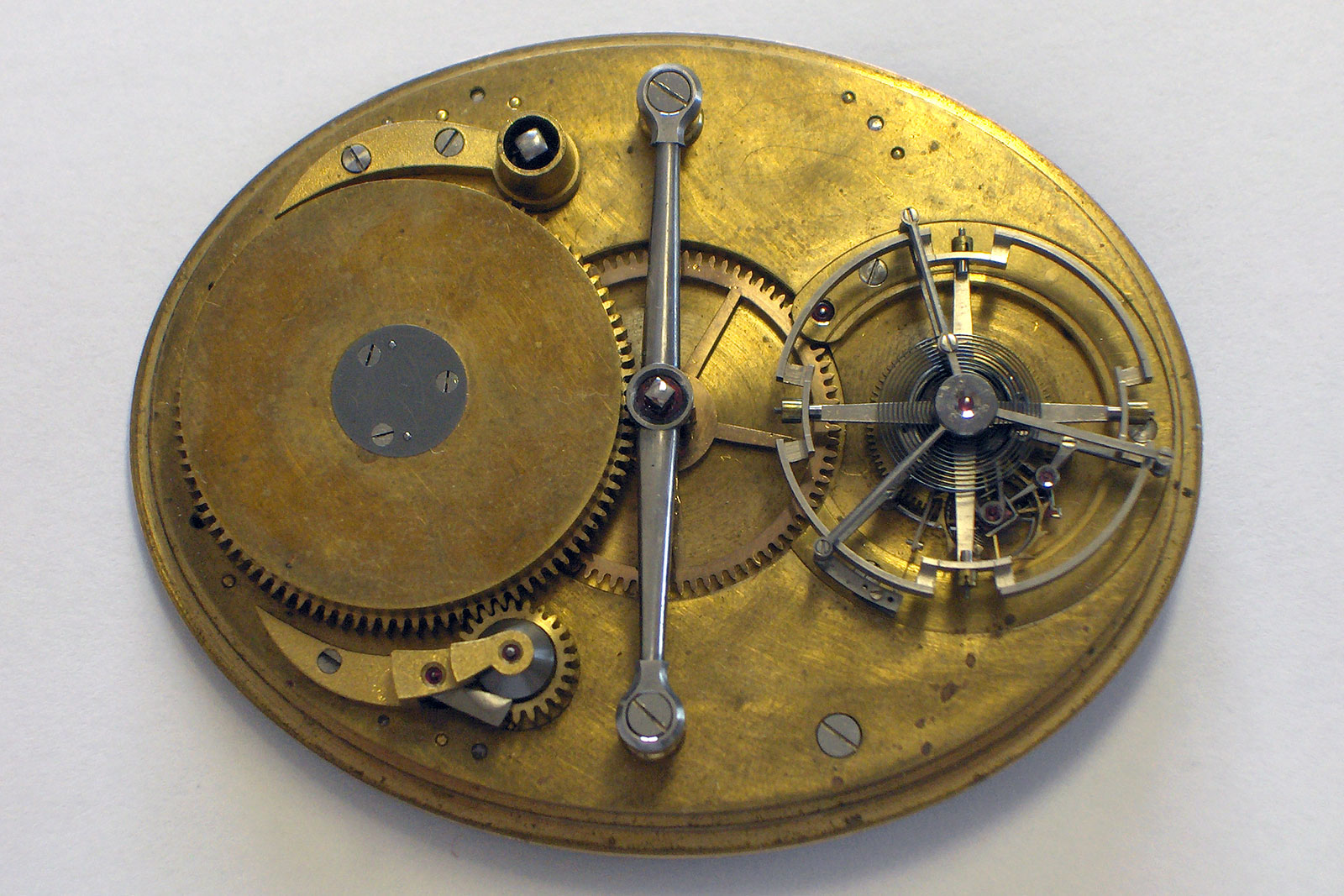

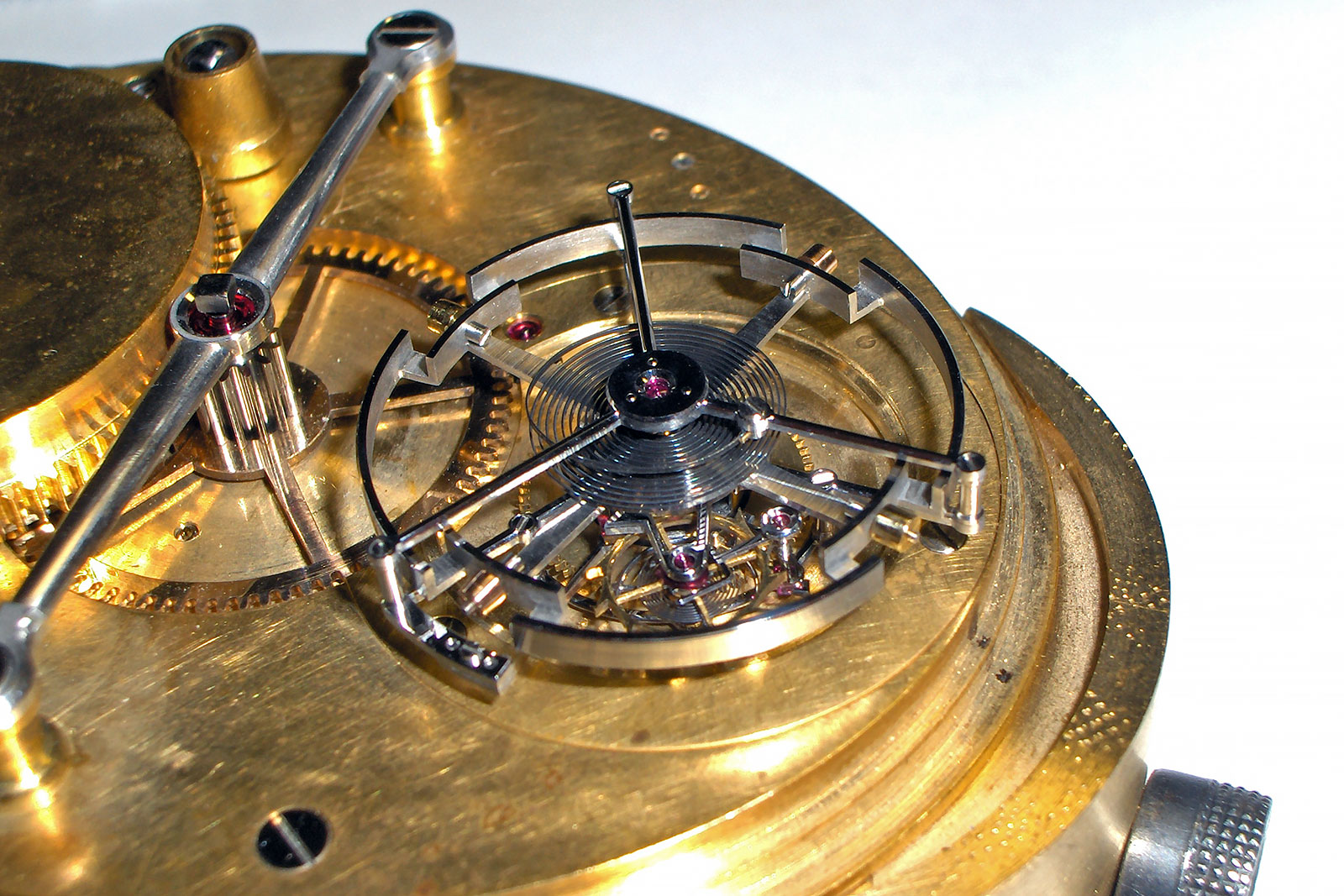

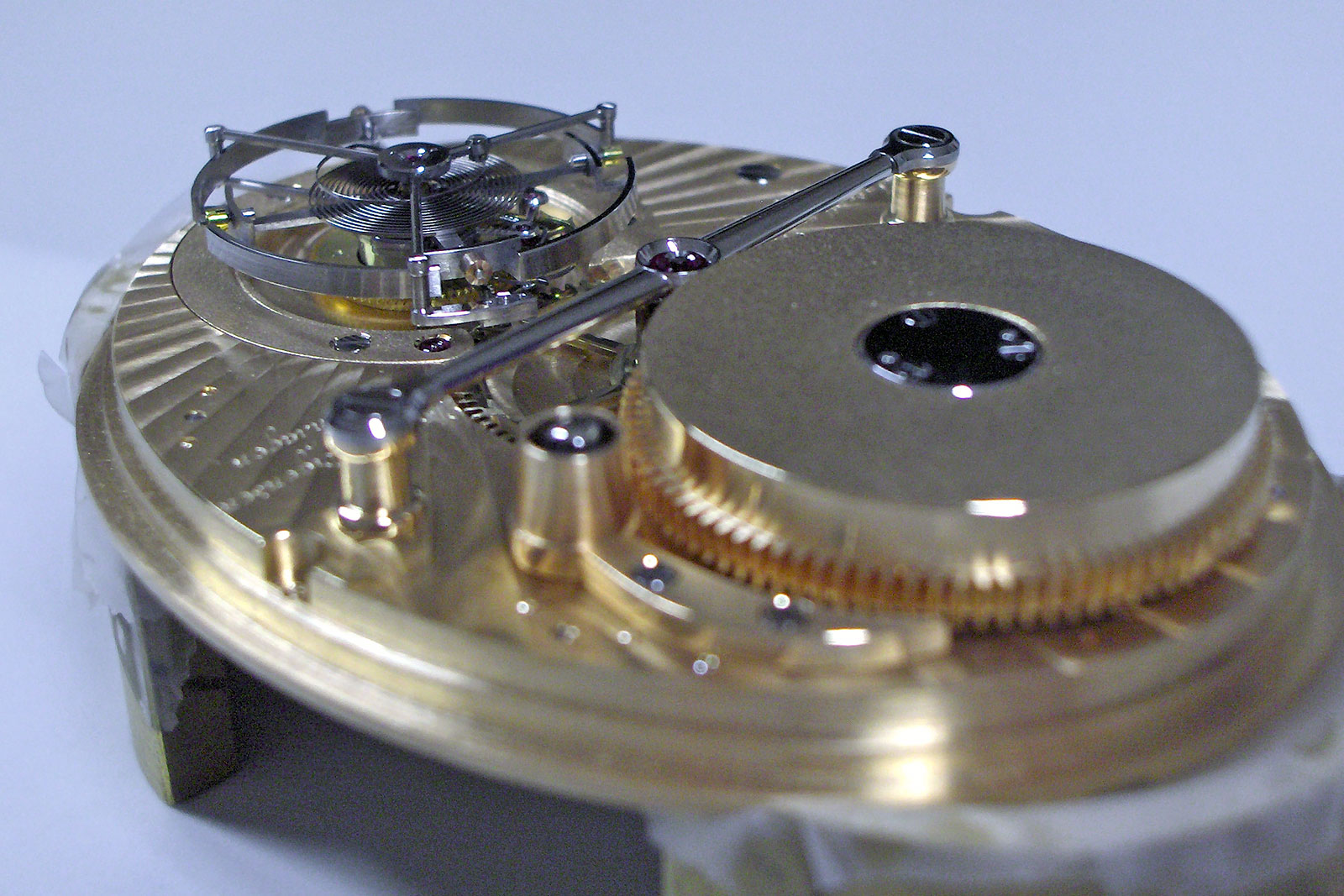

A hinged lid on the reverse reveals the inner beauty of the watch. The concise layout of the movement showcases the numerous skills that were required to achieve the multitude of surface finishes found on every single detail. The layout of the gear train is focused on the ellipse’s longest, central-vertical axis. Derek located the tourbillon cage at the lower focal point and counterbalanced it with the mainspring barrel at the upper focal point. Symmetry, harmony and deep insight into the mechanism were the guidelines of his design. Note that nothing is hidden by structural elements: the “flying”, bearing-based design of tourbillon cage and mainspring barrel do not require any bridges or cocks. An elegant central bridge for the minute wheel marks out the ellipse’s minor axis. The bridge’s evenly rounded, polished arms make you perceive it to be even more delicate and fine due to the way it catches the light, reflecting either black or white at different angles.

The oval movement

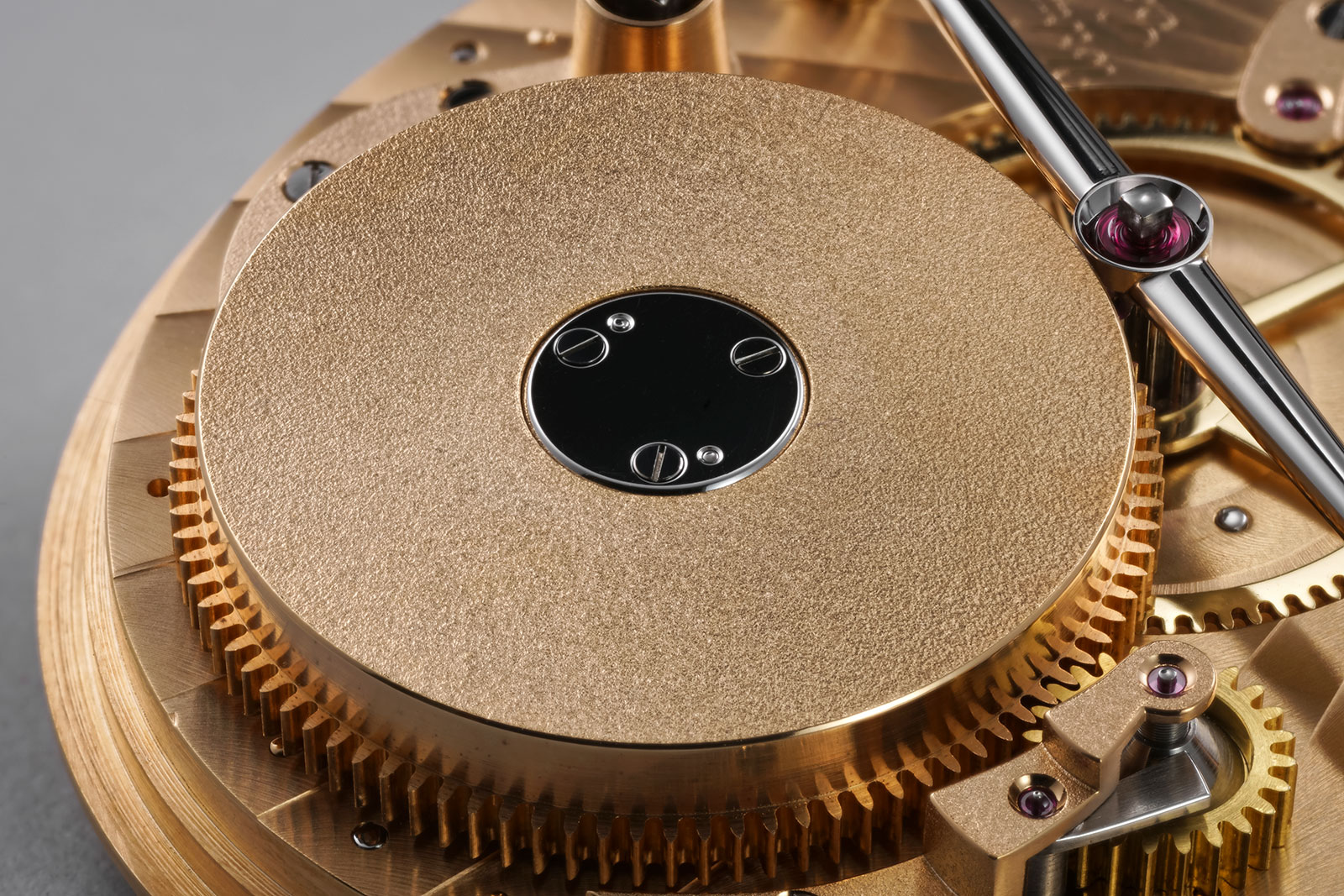

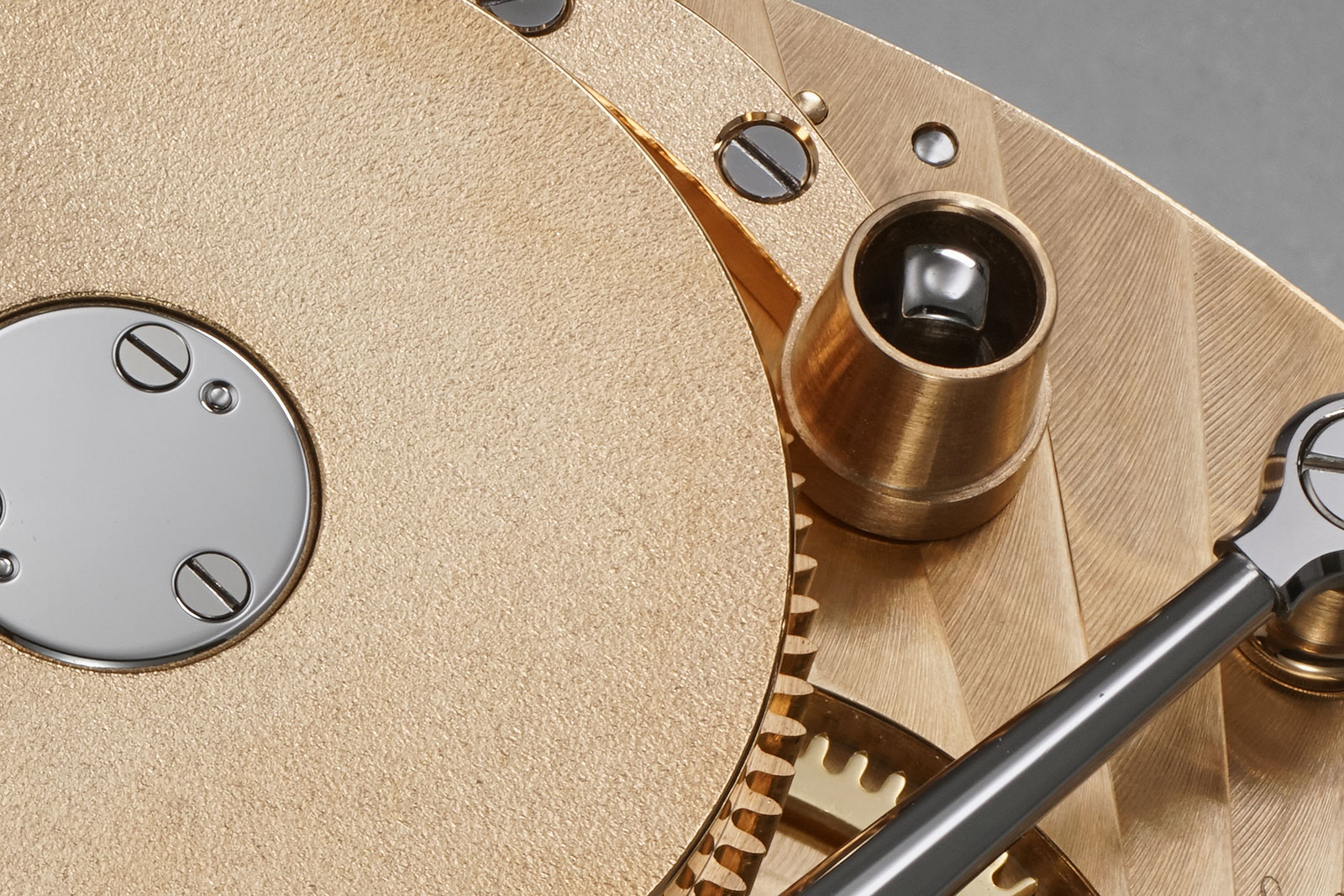

Rightly regarded as a holy grail of horology, the gilt, oval movement features a central minute-wheel bridge, “flying” mainspring barrel, and one-minute tourbillon with “flying” cage, as well as a remontoire and Earnshaw-style spring-detent escapement.

The calibre is an encyclopaedia of exemplary finishing. A huge variety of grained, matted, ground, polished, flat-polished, and damascene decoration was applied in a natural and logical manner with techniques mastered perfectly by Derek.

He arranged all kinds of different techniques throughout the watch to obtain a diversity of surfaces – sparkling, glossy, shiny, or scattered radiation – making it a great pleasure to contemplate the mechanism. Even if you look at it for hours, you will still discover new, breathtaking details.

Look at the radiating, striped pattern ground on to the main plate, which focuses the eye on the tourbillon cage located at the ellipse’s lower focal point. Derek ingeniously designed it as the great Renaissance painters did with golden haloes in their trademark portraits of saints.

The flying tourbillon cage has been removed to illustrate the quality of the usually hidden parts of the movement. All the wheels were polished and then plated with yellow gold, whereas the barrel cover and cock were grained with a steel-wire beater brush. Image – Jess Hoffman

Detail view of the movement with flying mainspring barrel. Please note the superb variety of finishes Derek applied just to this single part: The barrel drum is polished to reflect the teeth, the cover surface is grained to show a leather-like matt finished structure and a beautiful contrast is obtained with the burnished bevelled edges of the component and the black polished steel parts. The grained textures applied to the power-reserve cock down right use a completely different technique and appear more sparkling than the barrel-cover. This large variety of different finishing methods makes it such a great pleasure to closely contemplate the masterpiece. Image – Jess Hoffman

The highly polished, conical minute-wheel bridge with the hand-setting square has a shallow bulge at each end, which have been black polished. That is just one amongst the various fine polishes found in the movement, a specialty of Derek, all elaborate and the product of a lot of skill and experience.

Naturally, the screws were also made by hand. They have relatively narrow slots, but one of them, however, has a larger slot, which confirms their handmade nature. The screw heads are polished flat, while the slots are lightly bevelled with a small facet.

Black polish: The flat surfaces of the central-minute bridge reveal a black, diamantine polish under certain lighting conditions. According to the specific angle of lighting, you will obtain either a bright, shiny surface or a completely dark one due to the total reflection. In the latter case, all light beams are directed away from the eye. This effect can only be obtained with a perfectly flat, polished planar surface. Even the slightest imperfection would emerge immediately. Skill, an immaculately clean environment, perfect materials, good spirits, and plenty of patience are needed to succeed with black polishing. Image – Jess Hoffman

The radiating movement decoration with Geneva stripes is arranged so that it emanates outwards from the heart of the movement, the tourbillon regulator. The engraving on the base plate was executed by hand and then red gold plated, which gives a nice warm tone. Image – Jess Hoffman

The countersinks for the jewels was made with a roller countersink and then polished to a high gloss. Image – Jess Hoffman

To the right of the mainspring barrel is the bridge for the winding square, which is the socket that accepts the key for winding the watch. Image – Jess Hoffman

The power reserve mechanism is clearly visible on the left side of the mainspring barrel. An elegant design that takes up little space, it is the same mechanism described by George Daniels in Watchmaking, the seminal tome that’s a how-to on building a watch from scratch.

A pinion engages the mainspring barrel teeth and drives a steel cone sitting on a threaded axle in counterclockwise direction whilst the watch is running. The axle only revolves during winding, which causes the cone to rise, and when the watch is running, the cone falls. On the cone itself, a spring-loaded lever senses its position, “reading” the state of wind.

The power reserve mechanism with the tiny steel cone at its centre. Image – Jess Hoffman

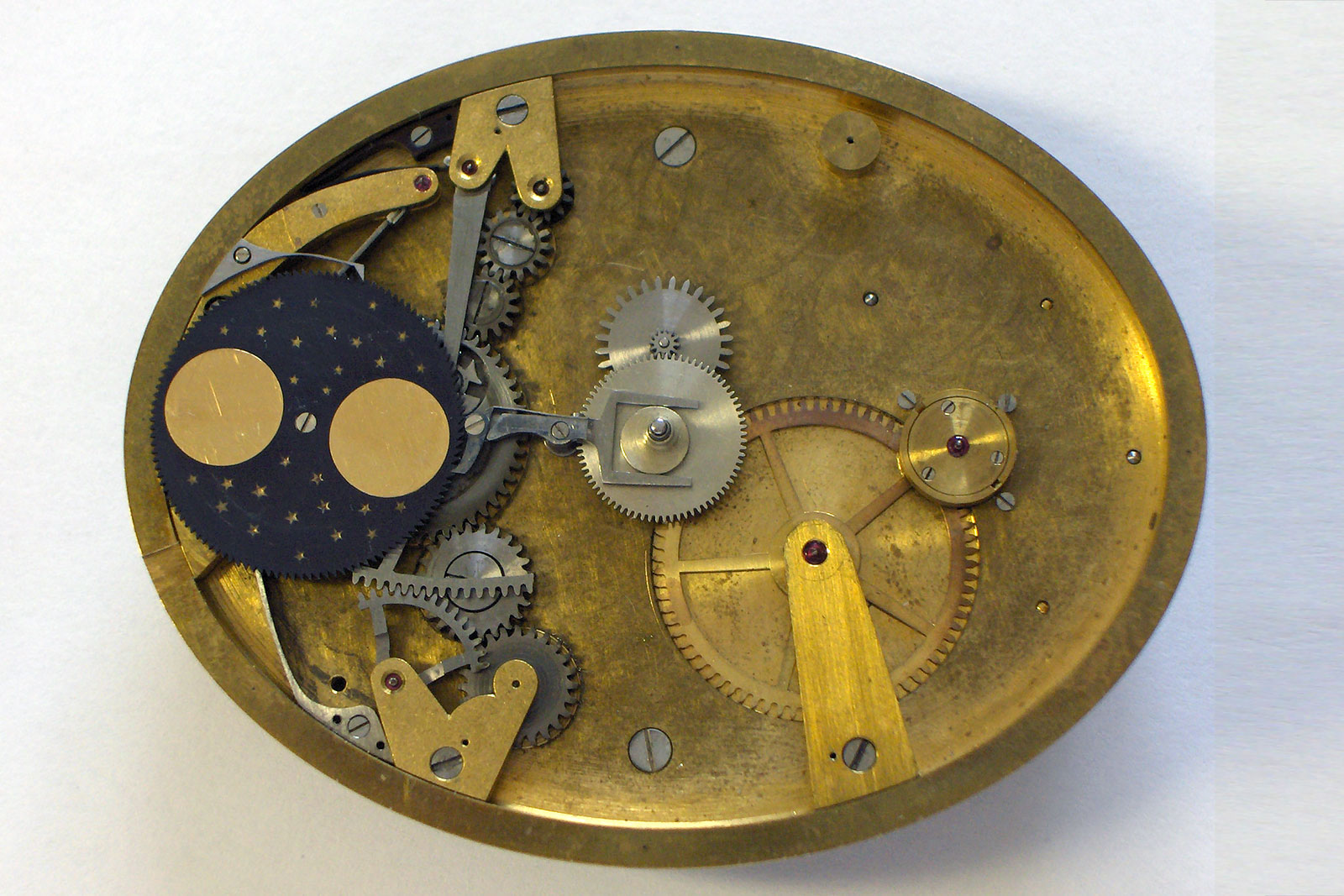

Under-the-dial

Despite being hidden, the movement under the dial is as neat and refined as its exposed side.

The main plate is covered with a precise, hand-applied spotting known as perlage. On the main plate sits the ratchet wheel with an integrated Maltese cross stop-work, along with winding wheels with wolf’s teeth. To the sides are the gears and racks of the power reserve display, along with the long, slender bimetallic spring for the thermometer.

Firmly attached to the hour wheel at centre is an eccentric, kidney-shaped cam that regulates the adjustment of the moon phase via a U-shaped fork. This very unusual, ingenious, and hitherto unknown device for a moon phase is probably an invention of Derek’s own, though it recalls the cam-and-fork mechanism of his remontoire, but in a slightly simplified way.

The under-dial view of the partially disassembled movement with the dial, tourbillon cage, and moon phase disk removed. The large third wheel of the gear train and the mounting holes of the lantern bearing of flying tourbillon are visible in the upper section, with the motion works in the centre. In and around the lower focal point of the ellipse you can see the mainspring barrel’s ratchet wheel with integrated Maltese stop work, intermediate gears for winding, as well as the power-reserve gears on the right of the barrel, and bimetallic spring of the thermometer on the lower left. Image – Jess Hoffman

The enlarged view shows the great effort in finishing Derek applied even to the components hidden under the dial. All the steel parts are finished to a very high level, while the main plate is decorated with sober perlage – it is unusual to find this pattern so impressively applied with such compact, tightly-spaced circles. Note also the fine quality of the polished countersinks around the rubies and screw heads on the cocks. Image – Jess Hoffman

The tourbillon assembly

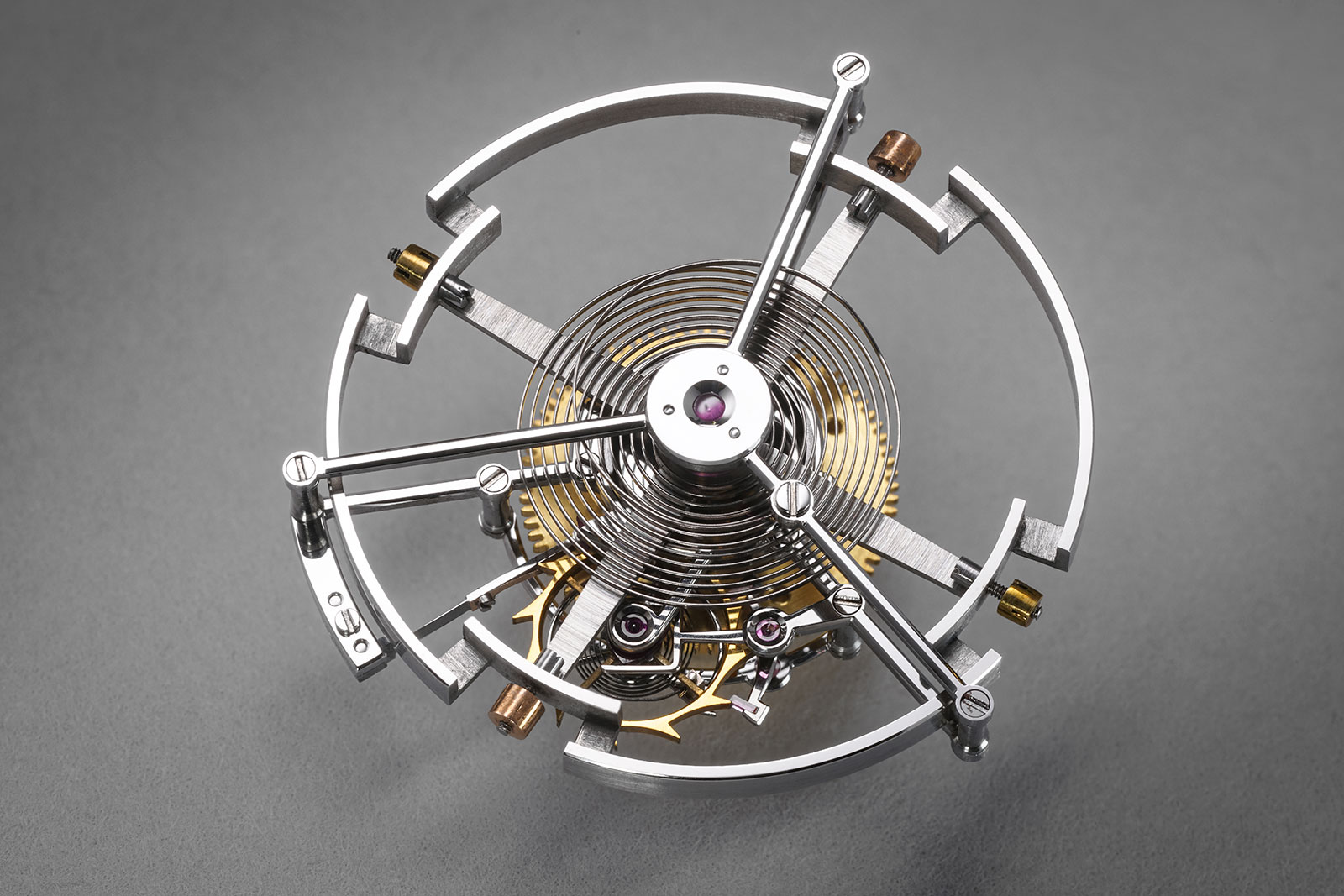

Invented by Pratt, the flying tourbillon with integrated remontoire is undoubtedly the highlight of the watch.

Before getting into the details of the manufacture of the tourbillon and remontoire, let’s remind ourselves of a few technical principles, as Derek himself did in 1991 when explaining the ideas behind his Urban Jürgensen tourbillon pocket watch with carriage-mounted remontoire in Horological Journal, vol. 134, no 1, published in July 1991.

“Many remontoire mechanisms have been made over the last 300 hundred years or so,” wrote Derek, “But, as far as I know, this watch is the first to have a remontoire incorporated in the carriage of a tourbillon and is, therefore, something new or innovative.”

“Moving into the present century an interesting remontoire is attributed to the Swiss company Barbezat-Bôle”, he continued, a watch that served as inspiration for his construction.

Amongst many considerations in its conception, the challenge was to overcome the inertia of the cage, which has to be stopped but then accelerated again 150 to 300 times per minute, depending on the escapement. One possibility is to make the wheels and their spokes as delicate as possible and to place the parts of the movement in the centre as far as possible.

Another possibility is to make an extremely light cage. This approach was taken to the limit by Professor Alfred Helwig and his students at the Deutsche Uhrmacherschule in Glashütte in the 1920s and 1930s, one of the reasons why Derek dedicated the Oval watch to Helwig.

The one-second remontoire made by Derek was akin to the Barbezat-Bôle design but a completely new approach to overcome the inertia of the cage, regardless of the fact that past work implemented interpretations of the aforementioned solutions. By installing the remontoire within the cage, a separation between the drive of the balance and the drive of the cage is achieved, solving the problem of inertia in principle.

The construction constitutes a real horological novelty. Derek was particularly pleased with the miniaturisation of the mechanism, which raises the question as to whether it might be the smallest remontoire ever made.

For Derek, the entire mechanical system of the movement represented a kinetic sculpture. “The first one gave me many headaches… but then it started to work correctly and I sat there, fascinated, watching the rapid series of events repeated with obvious regularity. I thought of Harrison perhaps doing the same thing when he got H4 running,” he recounted, “How do the watches perform? I can only give some short-term results as generally the watches have left my hands after a comparatively short time. I did have the opportunity to wear one of them for about a month, in very varied everyday conditions, including quite a lot of cycling. At the end of this period it was still within a few seconds”.

As Derek pointed out, the remontoire mechanism is very difficult to manufacture and requires extremely tight tolerances. After manufacturing, the parts have to be assembled and regulated very precisely.

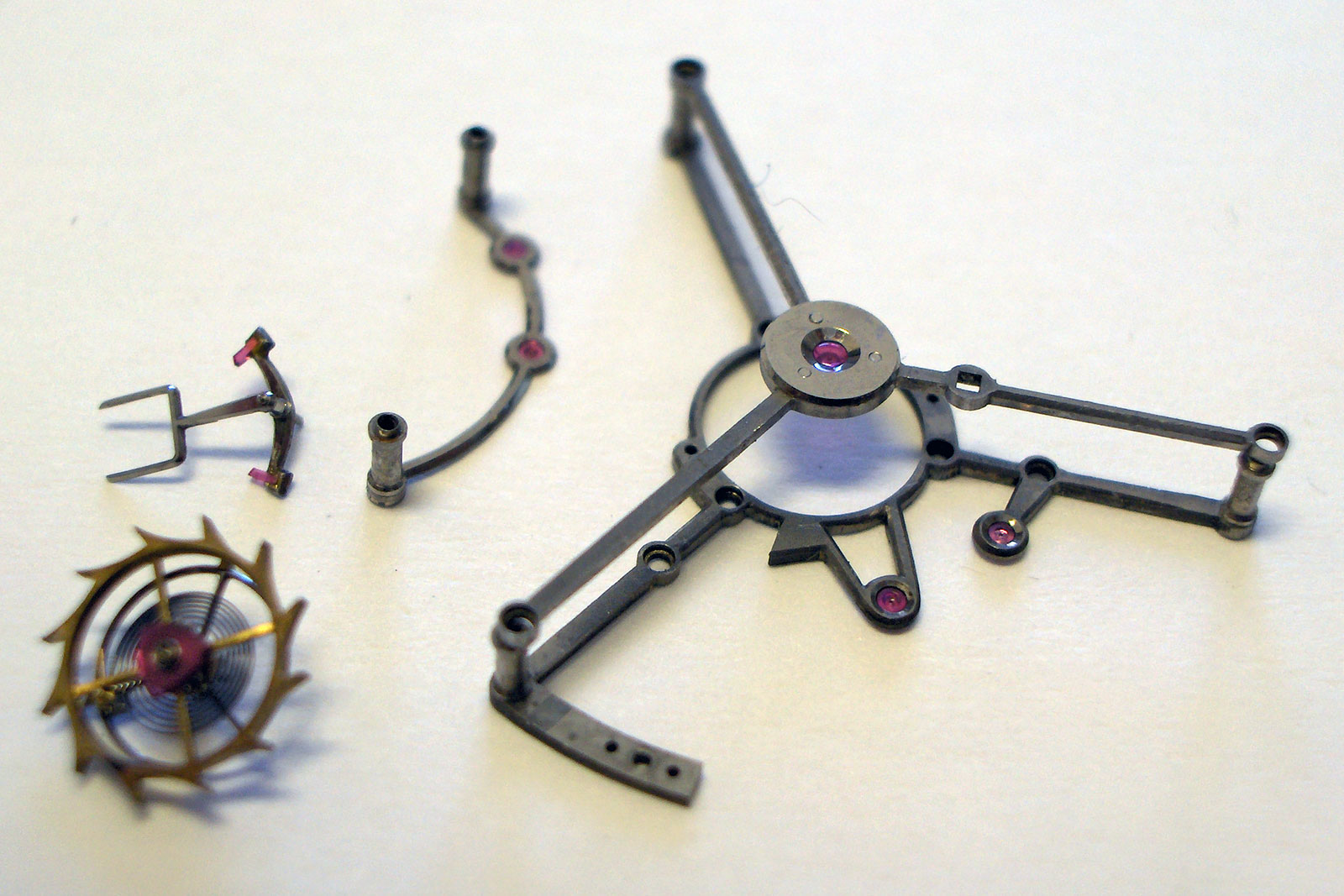

In the remontoire, the two escape wheels are arranged concentrically. The upper escape wheel with four spokes, and traditionally twelve teeth, is made of gold. The lower remontoire wheel for the impulse is made of steel and has three spokes and three teeth. Between the two wheels is a hairspring, which is then tensioned with each impulse. The spiral hairspring is the only energy source for the balance.

The wheel drive serves to tension the spiral spring of the remontoire once per second. The impulse to the balance is adjusted so that the balance reaches the ideal amplitude of 220°. The remontoire wheel is released every second.

The escapement wheel drive is riveted to the three-tooth steel remontoire wheel. The gold escape wheel sits loosely on the shaft of the escape wheel drive and is connected to the small spiral spring. This is retightened every second after another tooth has been released.

A culmination of micromechanics: the lightweight design of the tourbillon cage is absolutely impressive. On the upper left of the escape wheel, you can see the detent spring. The fork and locking anchor of the remontoire mechanism are clearly visible. Within the remontoire’s fork, you can see one of the three lobes of the Reuleaux triangle Derek shaped himself from ruby. Image – Jess Hoffman

The three-limbed heart is a Reuleaux triangle, which in this case consists of a ruby activated by the fork of the lever which releases, each second, one tooth of the remontoire escape wheel.

In the first remontoire version, the heart was still made of steel, but Pratt was uncomfortable with steel rubbing on steel. He finally made the meticulous ruby heart himself on a specially-equipped grinding machine, as depicted in photos accompanying his 1991 article in Horological Journal.

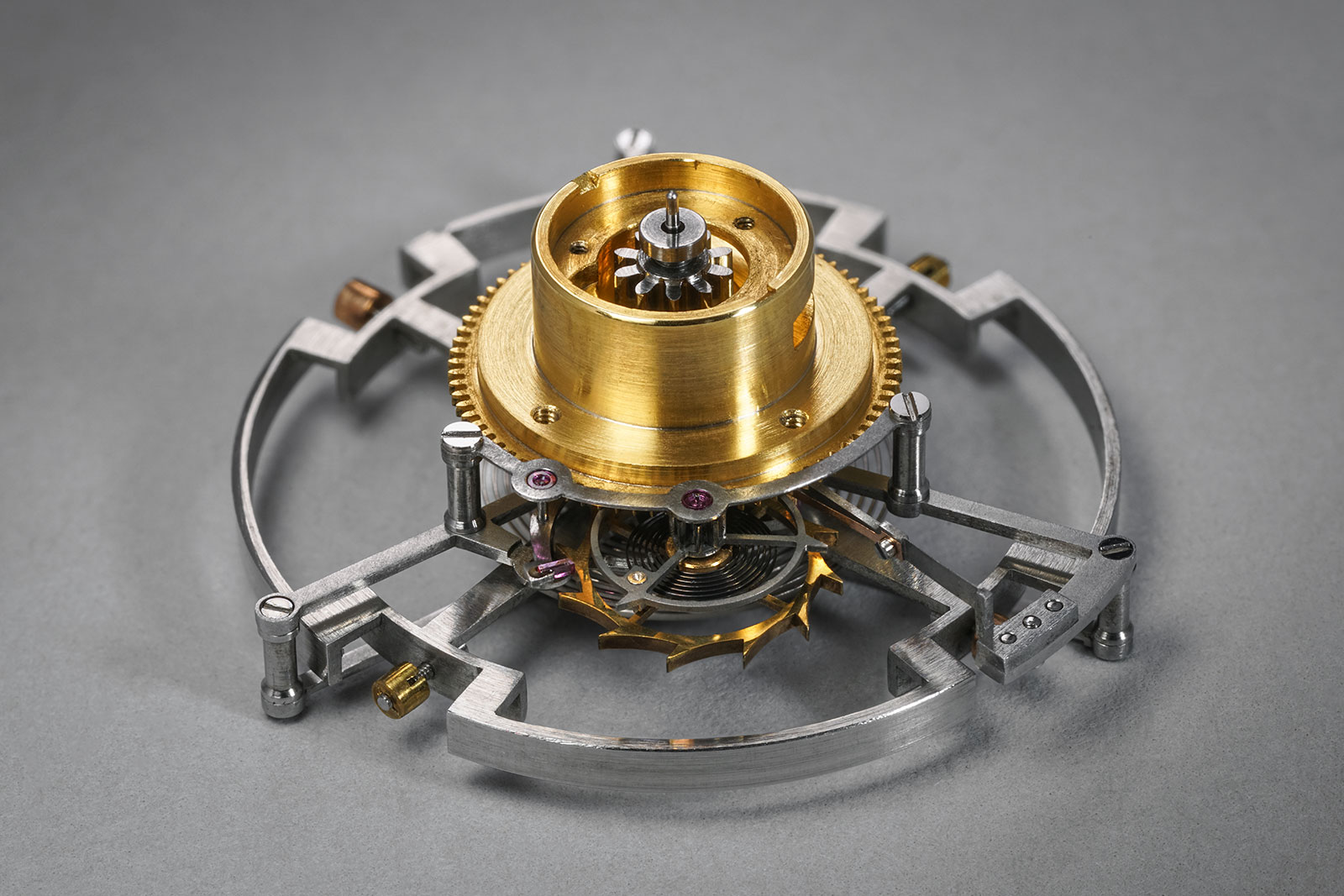

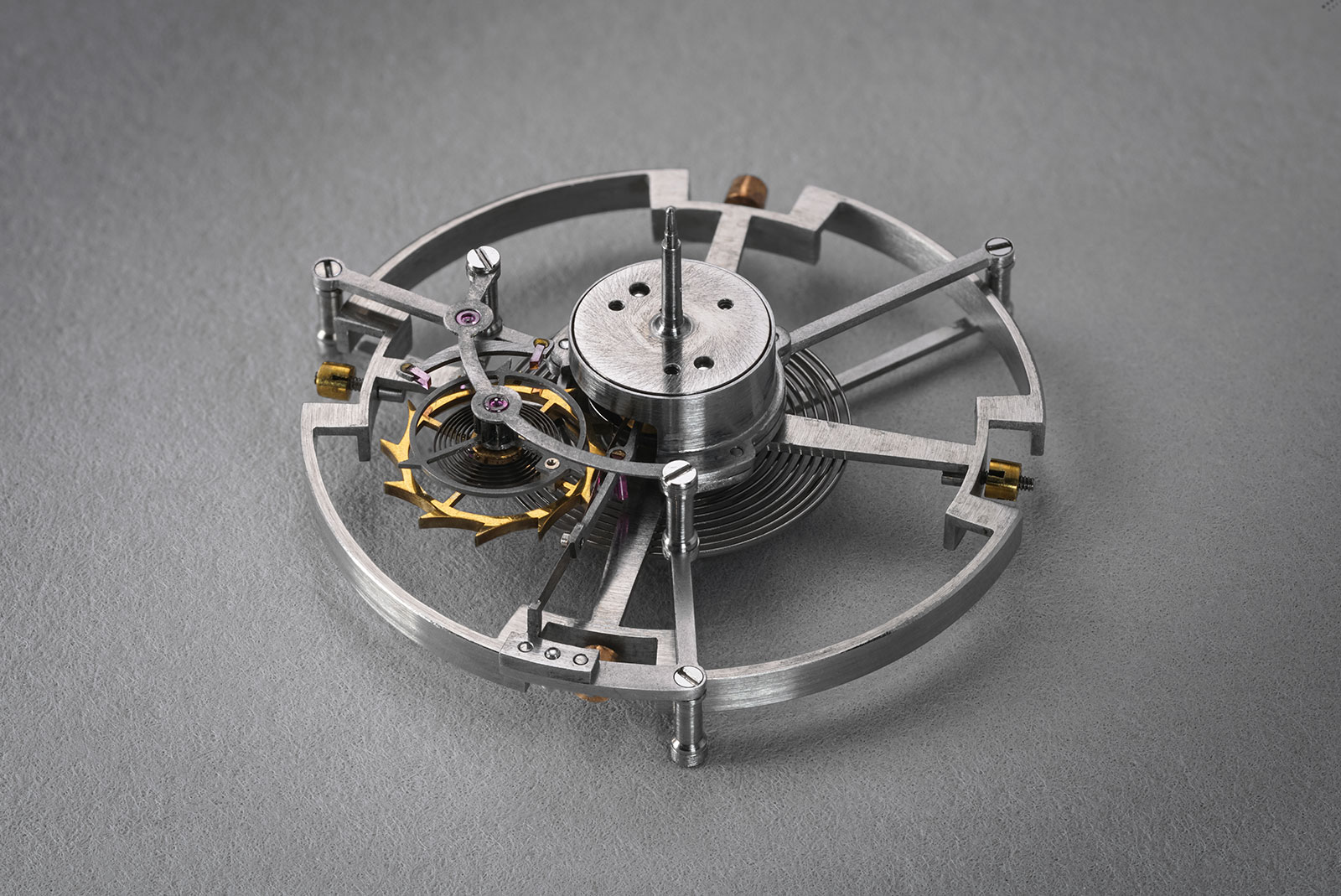

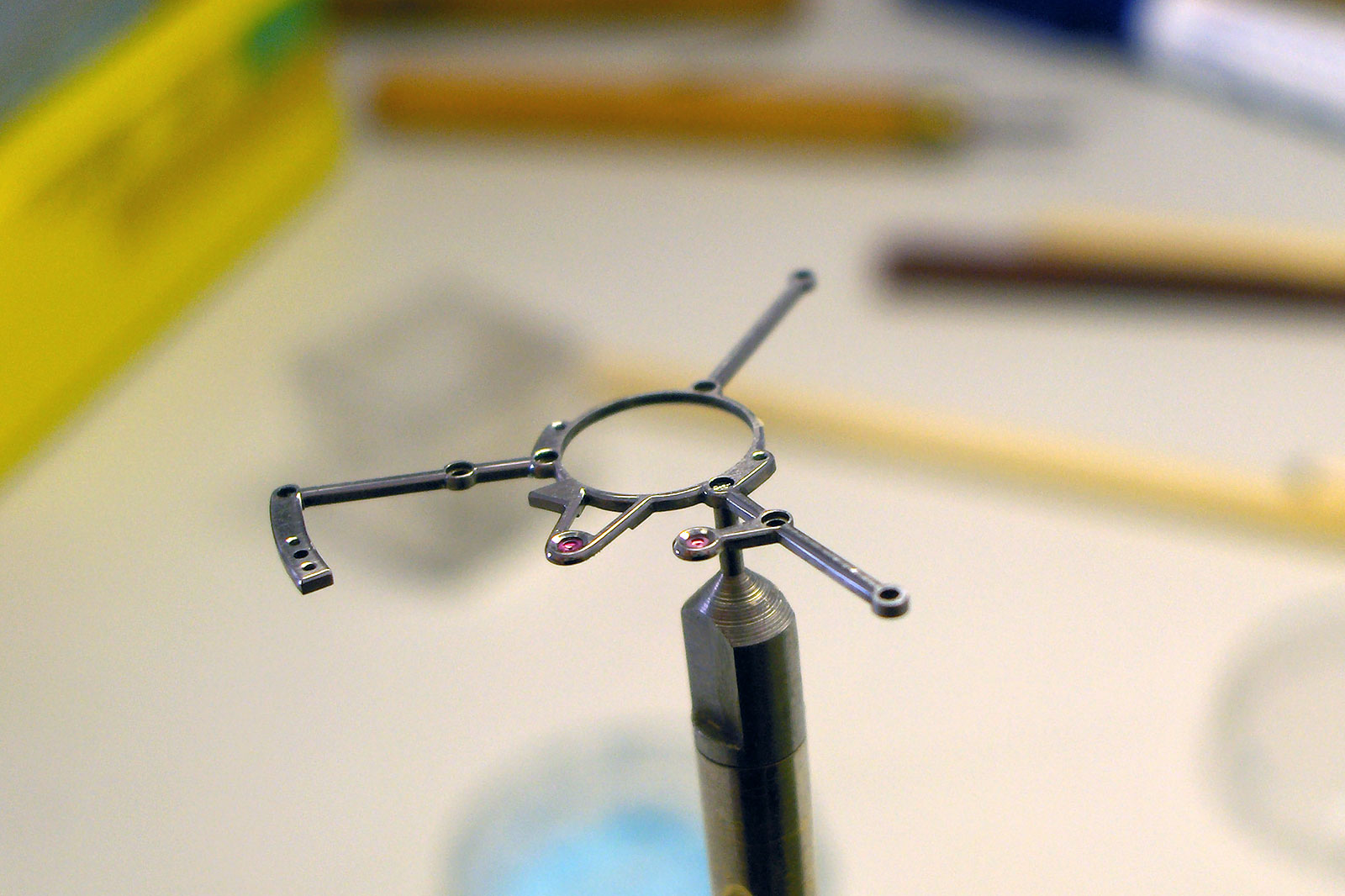

In plain view, the extremely delicate cage is faceted and highly polished with a 45° bevel. The cage was put on with an endstone plate and screwed from below.

The underside view of the disassembled tourbillon cage. The large brass structure in the centre is the “lantern”, which contains the bearings of the flying tourbillon. On its right flank, the lantern is slotted to enable the third wheel to mesh the fourth wheel pinion located in the lantern. One of the bearings is removed to show the fourth-wheel pinion normally placed between the jewels. Very precise manufacture is essential for minimal endshake of the tourbillon. You can also see the screw holes used to fix the bearing in the lantern and other screw holes to secure the lantern on the main plate. Image – Jess Hoffman

The transition to the bolted support pillars is very cleanly contoured and finely crafted. It is fundamental that the upper and lower cage bridges are not twisted. Unusual is the fact that the cage does not need a counterweight. There is only a bulge on the underside for attaching the detent spring. However, this has no influence on the center of gravity. Pratt probably overcame the balancing of the center of gravity by making the pillars of different thicknesses or from different materials.

The hairspring stud for fixing the hairspring’s outer end to the tourbillon cage is special. The hairspring was inserted into a small plate and then fixed with a screw. This is a delicate operation, as one has to be careful not to tighten the screw too much. The hairspring itself has a Grossman inner curve and an outer Breguet overcoil.

As for the balance, it is spectacular. It is monometallic, four-armed and turned from steel. The system for temperature compensating uses an Elinvar hairspring. The upper surfaces show a fine black polish. The inner flanks are circular-ground polished. The balance arms, on the other hand, are matt polished. The outer surfaces are also circular-ground polished. The four screws, probably made of gold, are used for fine adjustment. The balance beats at 14,400 oscillations per hour, and is identical to the one illustrated on page 224 of George Daniels’ Watchmaking.

The detent escapement is mounted in the lower cage bridge. The escapement parts are all finely finished and polished on all edges. The Earnshaw-style detent escapement has a flat gold escape wheel. Actually, for his tourbillons with remontoire Derek Pratt used to prefer a classic lever escapement, apart from two exceptions: his Tourbillon with George Daniels’ double wheel escapement and the present oval watch.

This view gives spectacular insight in the design of Derek’s constant force remontoire: The three-toothed steel remontoire wheel is riveted to the fifth pinion. The anchor releases it once a second. A spiral hairspring is fixed between the remontoire wheel and the detent wheel made from massive gold. This auxiliary spring is wound once a second by the remontoire wheel, thus periodically providing a specific constant driving torque to the detent escapement. In the center, you can see the long conical section normally carrying the fourth wheel pinion as described in the image above. The seconds hand normally sits on the pivot you can see in the upper section. Note the extremely delicate detent spring made from one piece of steel including the recessed stud – the spring section is only 0.03 mm thick. Image – Jess Hoffman

The guilloche face

Derek’s engine-turned dials are as legendary as his mechanical work. Like the movement, the harmony and symmetry of the complex dial are impressive.

The dial of the Oval watch is divided into three parts – all made of solid silver – and fixed onto the main plate with four screws at two, four, eight, and 10 o’ clock. It incorporates a cutout for the moon phase at 12 o’clock, the hour chapter ring, and an astonishing overlapping large seconds counter at “6”.

Closeup of the dial at 12 o’clock – the hour chapter ring, minute track, signature plate, thermometer and power reserve segments were each delineated by a narrow, fluted border known as filet sauté.

The very fine pitch of different engine-turned straight line and rose patterns create superbly delicate surfaces to accentuate the different sectors of the solid-silver dial. The centre of the chapter ring is structured by horizontal straight-line barley corn pattern, the sweep-seconds subdial and the semi-circled lids of the moon phase indication are decorated with straight-line basketweave guilloche. The outer section of the dial is finished with a circular barleycorn pattern engraved with a rose engine.

Manufacturing the dial was a laborious, artisanal process that is almost non-existent in watchmaking today. Almost entirely engine turned by hand, the dial has all its shiny silver components circular polished, while the indications were finely engraved by hand and then covered with protective lacquer.

The cut-out for the moon phase, for instance, was sawn out by hand and reworked with a file to ensure the correct appearance of the moon phase. Even the moon disc is made of blued steel, with gold moons were pressed into the twin apertures, whereas the cut-outs for the stars were cast in gold – and then entire disc was polished.

The stepped motion of the moon phase is obtained by transmitting the rotary movement of the hour hand via an eccentric cam and fork to the pawl lever. The oscillating motion of the pawl pushes the moon phase disk two steps a day. This solution is ways more elegant than the commonly used pin fitted to the hour wheel. Derek’s design of the moon phase mechanism recalls the same principles he already used in his remontoire mechanism. Image – Jess Hoffman

After engine turning – by hand on manually-operated machines – the surface and hand engraving of the lettering, an evenly white surface was been obtained by bleaching and frosting, giving the engine-turned segments a warm tone. Today, this technique is usually omitted from engine-turned dials for reasons of cost and lack of manufacturing capability.

The process avoids a glossy surface finish that would otherwise distract the eye, while creating a beautiful contrast between the circular grained, slightly shiny chapter rings, the fan-shaped scales, and the surrounding matte white, engine-turned surfaces.

After riveting the seconds ring onto the main dial, the finishing touch was the application of protective lacquer, known as Zapon after the company that originally invented the substance. The protective lacquer is less thick over the tallest points of the engine-turned surfaces due to the capillary effect, so oxidation naturally occurs on those peaks at an earlier stage, which matches harmoniously with the overall, natural ageing of the Zapon coating.

Making the hands for such an exceptional, one-of-a-kind watch would be a special pleasure for any master watchmaker. Derek carefully handcrafted the solid-gold Breguet hands from one piece of gold.

The central parts of the hour and minute hands are each chamfered and polished. The asymmetrical “eyes” at the tips of each hand were created using a diamond-tipped milling machine. And the seconds hand has a shorter, button-shaped counterweight, thus making it cleverly balanced. Also in gold, he hands for the thermometer and up-down indication are extremely delicately worked.

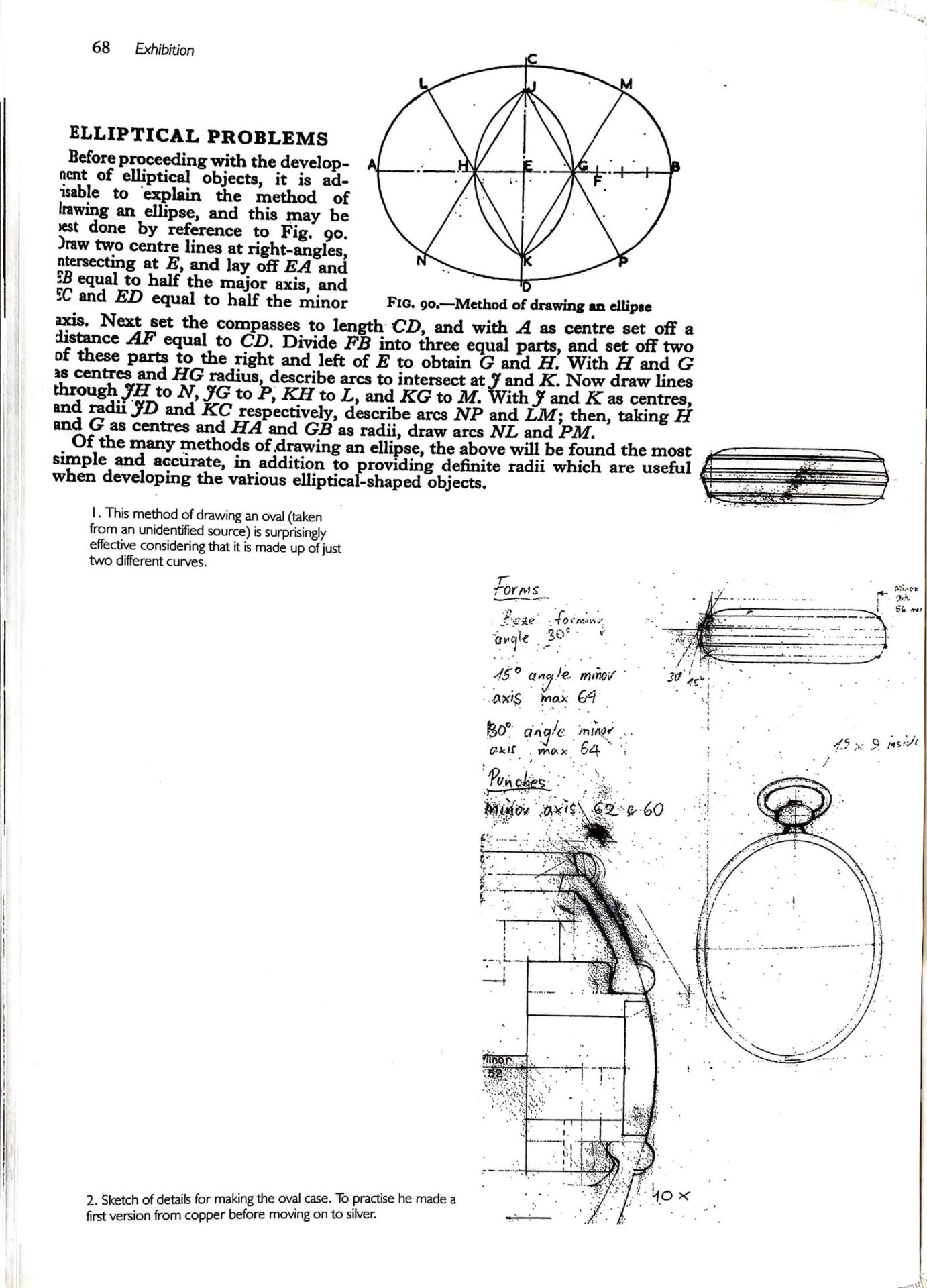

Fabricating the case

The case also represented a major challenge in the production of the Oval watch. In his 1993 treatise on oval watches in Horological Journal, Derek wrote, “Most frequently the first watches from the early 17th century were oval. Since then, only isolated examples of oval pocket watches have been made. Perhaps it was the added difficulty of making a case and glass with any shape other than round which led to the decline [of the shape]”.

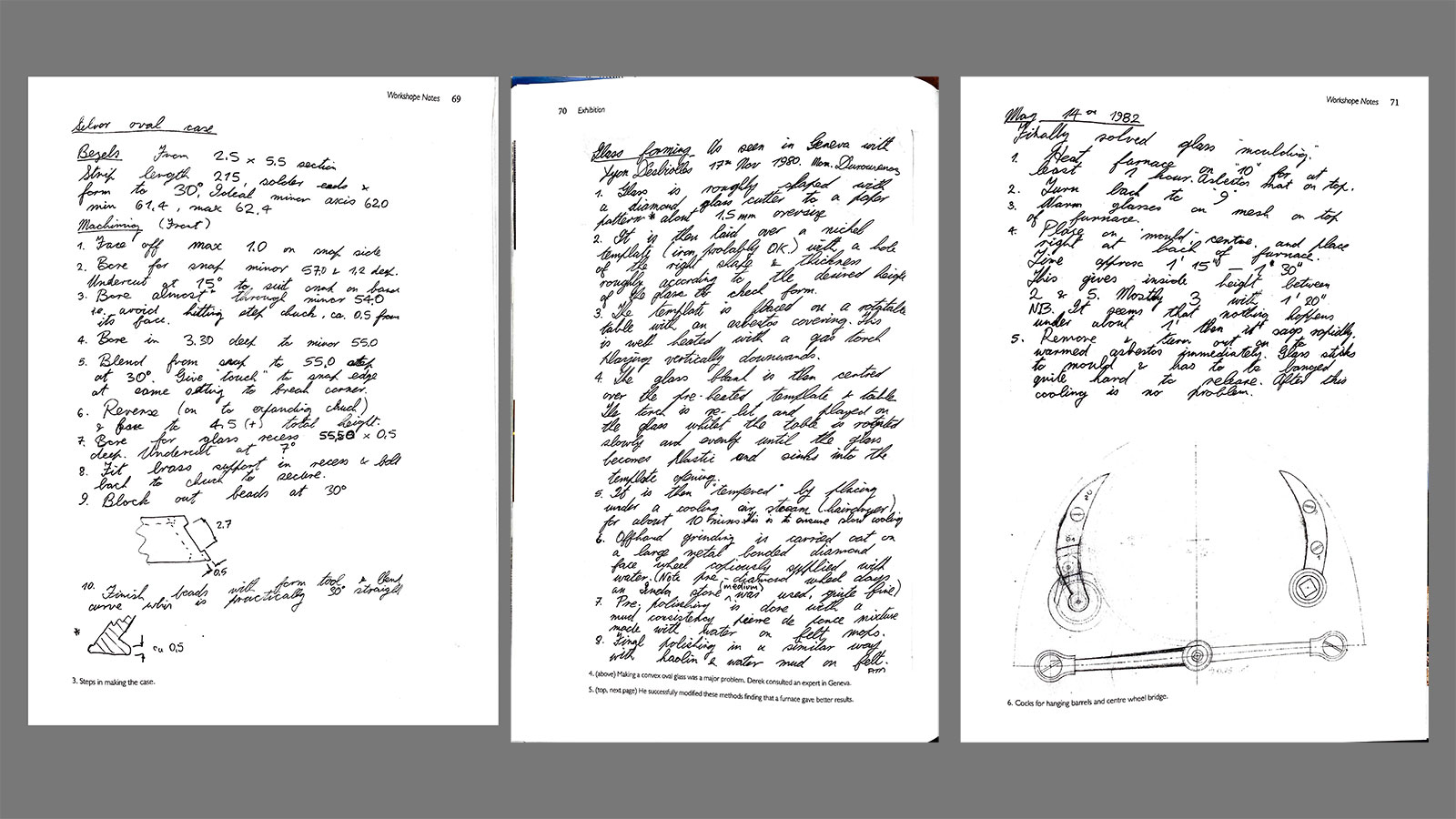

Sketch for the oval case, Derek Pratt FBHI Watchmaker, p. 68-69)

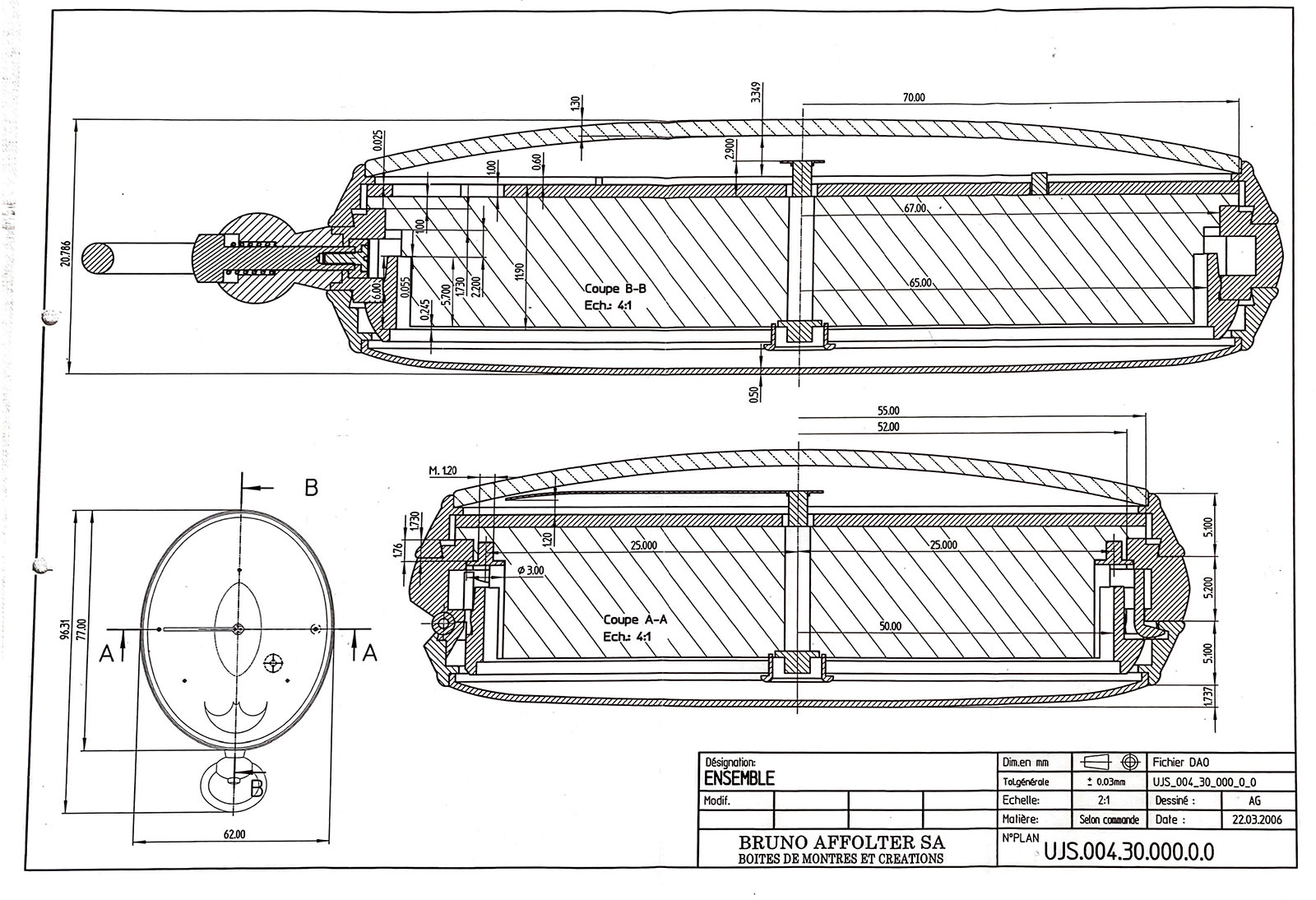

Three cases were made for the Oval watch. Derek made one in silver by hand with his lathe, and then a second in platinum and a third in red gold were produced between 2005 and 2006 by Bruno Affolter, a case maker in La Chaux-de-Fonds now known as Les Artisans Boîtiers (and a sister company of Parmigiani).

Although the latter two cases were probably made using with a CNC machine, they also required special skills to produce, especially for the platinum case, because of the brittle material and the required mirror polishing.

Platinum case drawing by Bruno Affolter

The main manufacturing steps for the silver case Derek made himself are explained in pages 355-370 of Watchmaking by George Daniels. However, there were several additional problems that had to be solved in order to obtain the oval shape.

The oval case consists of four parts: bezel, middle, back, and back cover. The pendant sits on the middle section and is complemented by the pendant ring and the push button to open the back cover and to reveal the movement, which is protected from dust by a sapphire crystal. The bezel and the outer rim of the back are outlined by profile rings, which lends the case a singular aesthetic and harmony.

All parts of the case were turned by hand on a lathe, which required a special attachment because of the oval shape. In particular, making and adjusting the silver strips for the sloping surfaces of the case demands a lot of skill, as Derek wrote.

For the chamfered form of the back cover, a silver plate was hammered into a mould. Finally, the three-part hinge of the back cover had to be soldered to the middle part at nine o’clock.

The hinged lid was ingenious, because the sprung lid opens via the push button at 12 o’clock, which is linked to the case spring at three o’clock. Because of the long lever arm connecting the two, the production of the case spring was a special challenge.

The Oval watch with its red gold and platinum cases

Finally, the individual parts had to be meticulously adjusted. The oval and chamfered crystal for the dial and the other crystal for the back had to be manufactured and fitted – both caused considerable difficulties.

The back crystal also features two silver-lined openings to access to the sockets for winding and hand setting. To solve the problem of making an elliptical crystal, Derek first “visited a man in Geneva, who was said to be the last man to make form glasses for any unusually shaped watches. [The man’s] initial response confirmed this to be the case… [but] on giving the size [his] tune changed dramatically”.

According to the specialist, the glass that Derek wanted was too large at 57 mm by 72 mm), so he treated Derek as if he were mad. However, Derek didn’t give up and decided to make the glass himself. After many attempts, he managed to make one.

Derek’s workshop notes in 1982 about case and glass fabrication of the oval watch page 69 – 71 Derek Pratt Watchmaker 1st edition

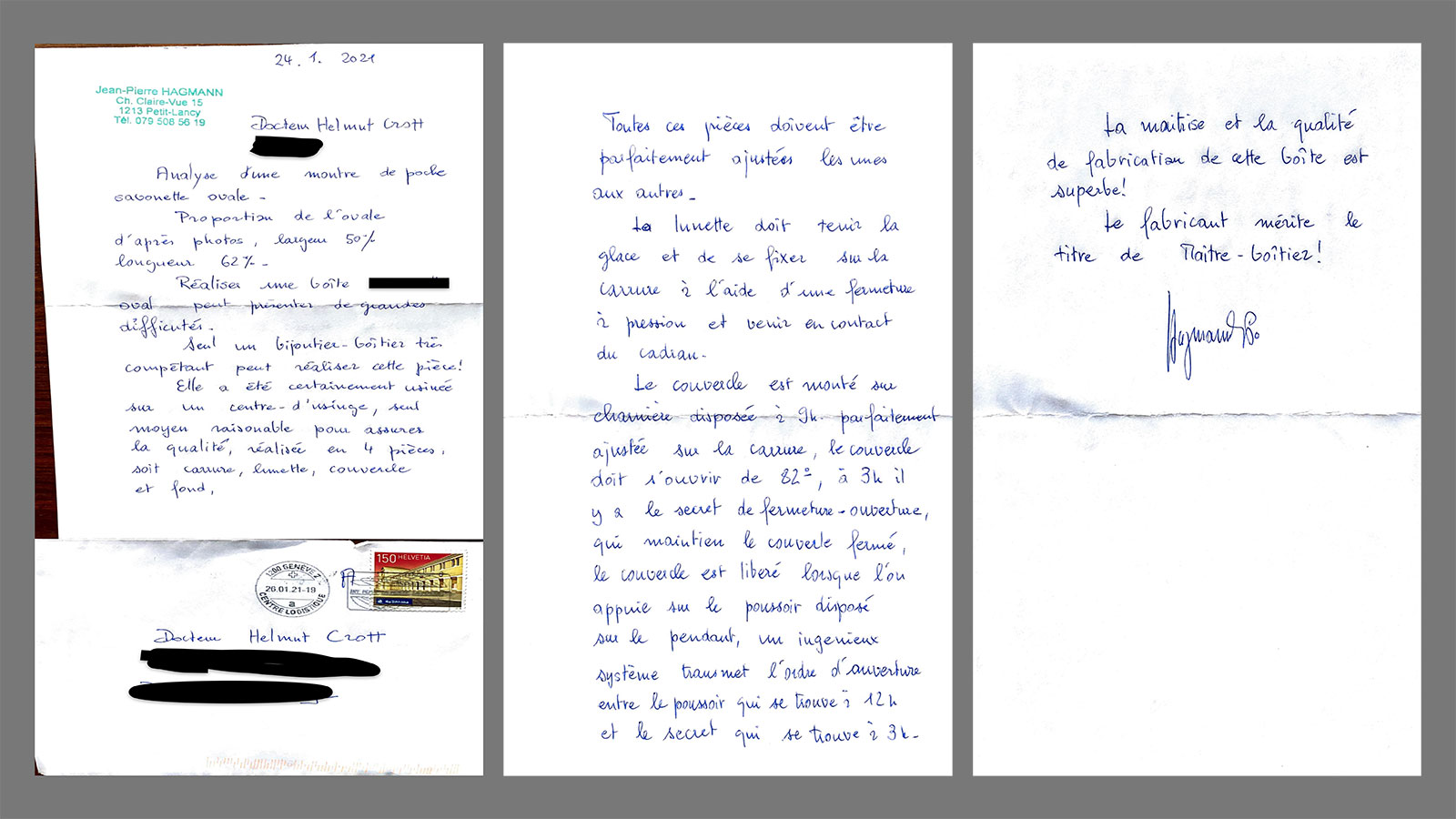

My friend Jean-Pierre Hagmann, an experienced case maker, examined Derek’s silver case and remarked in a letter he wrote to me, “The rings are particularly difficult to solder on silver cases. Opposite of gold cases, one has to heat the ring as a whole.”

Jean-Pierre, who was full of admiration for all three cases, also noted: “The production must have been a considerable challenge – the result is impressive”.

Jean-Pierre Hagmann

A letter from Jean-Pierre Hagmann detailing the background of the Oval watch case

He closed the letter by saying, “La maîtrise et la qualité de fabrication est superbe! Le fabricant mérite le titre de Maître-boîtier!”. That translates as “The mastery and quality of manufacture is superb! The maker deserves the title of master case maker!”

Addendum January 12, 2022:

After this article was published, Kari Voutilainen got in touch to provide additional information about the completion of the Oval pocket watch. He also provided photos of the movement as it was being completed in his workshop, which have been reproduced here.

According to Mr Voutilainen, the ebauche for the Oval watch was completed by Derek Pratt in the early 2000s. In 2004, Peter Baumberger asked Pratt for permission to hand over the project to Mr Voutilainen. By then Pratt was already suffering from the cancer that would later claim his life, and he was glad to have Mr Voutilainen finish the movement.

The mostly-complete ebauche

The under-dial view of the ebauche

And from the side, revealing the depth of the movement

Most of the movement was already complete by then, says Mr Voutilainen, although the movement was not functional. It took Mr Voutilainen’s workshop over a year to finish the movement, including producing the missing parts, applying decoration, and adjustment.

Mr Voutilainen’s work also extended to the case. While the cases in gold and platinum were made by Bruno Affolter, he was responsible for the springs for the closure and hinges of the case.

Parts of the unfinished tourbillon

The tourbillon cage as anglage is being applied

After the radial striping had been applied to the base plate

The finished movement in all its glory

Literature

Crott Helmut, “Derek Pratt, Watchmaker”, in Derek Pratt FBHI Watchmaker, Proceedings of a Memorial Seminar, British Horlogical Institute, Upton Hall, September 18th 2011, ed. by Timothy Treffry, London, British Horological Institute, 2012, p. 25-31 (1st ed.).

Daniels George, Watchmaking, London, Philip Wilson Publishers, 1999 (2nd ed.).

Knudsen John M. R., The Jürgensen Dynasty: Four centuries of watchmaking in two countries, Urban Jurgensen, 2013.

Pratt Derek F., “Oval Watches”, Horological Journal, vol. 135, no 10, April 1993, p. 336-337.

Pratt Derek F., “A Tourbillon indicating full seconds with carriage-mounted remontoire, twin barrels and up and down indicator, made for Urban Jürgensen & Sønner, Copenhagen”, Horological Journal, vol. 134, no 1, July 1991, p. 9-15.

Treffry Timothy, “Workshop Notes”, Derek Pratt FBHI Watchmaker, Proceedings of a Memorial Seminar, British Horlogical Institute, Upton Hall, September 18th 2011, ed. by Timothy Treffry, London, British Horological Institute, 2012, p. 67-72 (1st ed.).

A medical doctor by training whose love for timepieces compelled him to switch careers, Dr Helmut Crott is a storied name in the world of vintage watches and international auctions. He established Dr. Crott Auctioneers in 1975 and sold the business in 1993 to become a specialist in vintage Patek Philippe watches. Dr Crott acquired Urban Jürgensen & Sønner (UJS) in 2011 upon the passing of Peter Baumberger.

Back to top.