Winners Take All: How a Handful of Brands Dominate the Secondary Market

The market is booming. The winners are few.

Industry price data provider EveryWatch has released its annual report on the state of the secondary market for luxury watches. The data confirms what many collectors already sense — the pre-owned watch market is booming, but the gains are concentrated in a small number of brands and references that are capturing the lion’s share of value, while the rest are left fighting over the scraps.

Francis Ford Coppola’s personal F.P. Journe FFC prototype (left) sold for US$10.8 million, while his Chronomètre à Résonance sold for US$584,000 in December 2025. Image – Phillips

Initial thoughts

There are many reasons to be skeptical about much of the information gathered by industry data providers. For one thing, data gathered from dealers, internet listings, and auctions naturally misses the sizable proportion of transactions that happens offline. For another, the asking price is often easier to find than the clearing price, which tends to be lower.

That’s not to say the data is unusable. On the contrary, the time series data gathered by data providers like WatchCharts can provide validation (or not) for anecdotal evidence and help collectors and dealers make more rational point-in-time decisions — if there is such a thing as a ‘rational’ watch purchase.

What’s interesting is not necessarily that the market is estimated to be about US$20 billion in size, or that it’s growing at a rate in excess of 30% according to EveryWatch. What is more interesting is how the spoils of this market are divided up, and how individual brands have reacted (or not acted) to capture some of this value.

Market snapshot: winners and losers

While concrete figures are elusive, EveryWatch estimates that Rolex, Patek Philippe, and Audemars Piguet together account for more than 50% of transactions by value on the secondary market – nearly US$10 billion combined. According to WatchCharts, the data provider behind the annual industry report from Morgan Stanley, these three brands are the only high-volume brands with a positive overall value retention (VR) ratio, which measures the spread between retail and secondary market pricing.

The drop-off from third place to fourth is steep; by value, secondary sales of Audemars Piguet watches were more than double those of Omega in fourth place. That said, almost every major brand recorded a double-digit increase in secondary market unit volume in 2025, even has pricing held steady. The upward year-over-year trend is notable, and more believable than the absolute values, since the data was captured in a similar fashion at each measurement.

This Vacheron Constantin ref. 6448 with a brushed platinum case and diamond dial sold for CHF698,500 in 2025.

In this context, Vacheron Constantin delivered especially strong results, with unit sales and value up more than 50% on the back of a 5% increase in median price. Richard Mille’s secondary market activity, supported by its own certified pre-owned (CPO) programme, delivered a similar performance profile. Conversely, Hublot was the only brand in the top 25 to see a decline in volume, according to EveryWatch.

Whether up or down, these headline brand-level figures are not that useful for most market participants. What matters more to collectors and dealers is the performance and current market price of specific references. For this data, WatchCharts data paints a picture that’s a microcosm of the larger industry – the overall winners are propped up by a handful of winners of their own.

In other words, an outsized proportion of market value is accruing to a relatively small number of references, primarily the popular sport watches of our time like the Patek Philippe Nautilus and Aquanaut, the Rolex Daytona and GMT-Master, and the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak.

The Audemars Piguet Royal Oak ref. 16202.

The latter is a perfect example, with references in this collection trading at an average premium of nearly 25% above retail, according to Morgan Stanley and WatchCharts. By comparison, the same data shows Royal Oak Offshore and Code 11.59 models trading at double-digit discounts.

In the same way that weakness in an economy can be masked by the over performance of a small number of companies, like the so-called Magnificent Seven stocks in the United States, a relatively small number of references are solely accountable for the positive VR ratios of Patek Philippe, Rolex, and Audemars Piguet. The key takeaway is that even the winners have a few losers.

The hype cycle

Interestingly, only two brands enjoy secondary market transaction volume roughly equivalent to their annual production. According to EveryWatch, about 4,400 A. Lange & Söhne watches changed hands publicly last year, while the number of F.P. Journe watches transacted was just over 1,000. This volume represents about 88% of Lange’s annual production, and a little more than 100% of F.P. Journe’s capacity, respectively. Patek Philippe was third, with public transactions accounting for about 40% of the brand’s annual production.

This symmetry is surprising because Lange and F.P. Journe have vastly different VR profiles, and many popular Lange models can be found below retail on the secondary market. What explains this? The same data suggests the median F.P. Journe watch sits on the market for an industry best 36 days, while the median Lange takes 53 days to sell. That can’t be the only explanation, however. Judging by the median, both brands sell through faster than either Patek Philippe or Audemars Piguet, which take 61 and 77 days to sell, respectively, and are among the brands with the best overall VR ratios in recent years.

This A. Lange & Söhne ref. 117.040 Grand Lange One produced for Paris retailer Dubail sold for nearly triple its high estimate at Phillips in 2024. Image – Phillips

The effect is more likely psychological – the hype becomes reality. In this sense, buyer emotion and the fear of missing out (FOMO) provides a more complete explanation for the lopsided performance of closely matched brands, especially within niche segments like independent watchmaking. For low-volume brands or highly desirable limited edition series, small shifts in sentiment can deplete inventory quite quickly, causing a frenzy.

This also helps explain why the performance of many brands rests on a few trophy models considered ultra-desirable at any given time. Naturally, special off-catalogue models from big brands and early production pieces from independents tend to outperform. Case in point, the F.P. Journe Chronomètre à Résonance Souscription no. 2 sold for more than CHF3 million in November 2025, more than three times its high estimate.

Special boutique limited editions have also been out-performing benchmarks, at least for editions that are tangibly appealing in their own right. Recent examples include the fan-favourite F.P. Journe Octa Perpétuelle Tokyo boutique edition and the A. Lange & Söhne ref. 117.040 Grand Lange One produced for Paris retailer Dubail.

Auction snapshot

The winner-take-all dynamics at play in the broader market can be observed at a smaller scale in the salerooms of the major auction houses like Phillips, Christie’s, and Sotheby’s, though there are some additional nuances to unpack.

Tony Traina’s lot-by-lot analysis of last fall’s Geneva auctions on Unpolished showed that Patek Philippe, Rolex, and Audemars Piguet together accounted for more than 60% of total lots. This combined market share is similar to what EveryWatch has observed about the broader secondary market, but in the rarified air of elite auctions Patek Philippe takes the top spot from Rolex with more than 30% of total lots.

Auctions are interesting in part because auction houses provide pre-sale estimates for each lot. In some ways, this process is analogous to the way equity analysts produce estimates ahead of earnings season, offering investors a way to anticipate and contextualise a company’s financial performance.

The enthusiasm for F.P. Journe watches continued apace into December, when Francis Ford Coppola’s own FFC prototype broke eight figures including fees. Image – Phillips

The estimates are simply that — estimates — but they nonetheless represent a reasonable assumption about market value, with one caveat: auction houses have a built-in incentive to low-ball estimates, since over-performance looks better after the fact. Fortunately, this impulse is tempered by the need to win new consignments from clients and build hype around each lot.

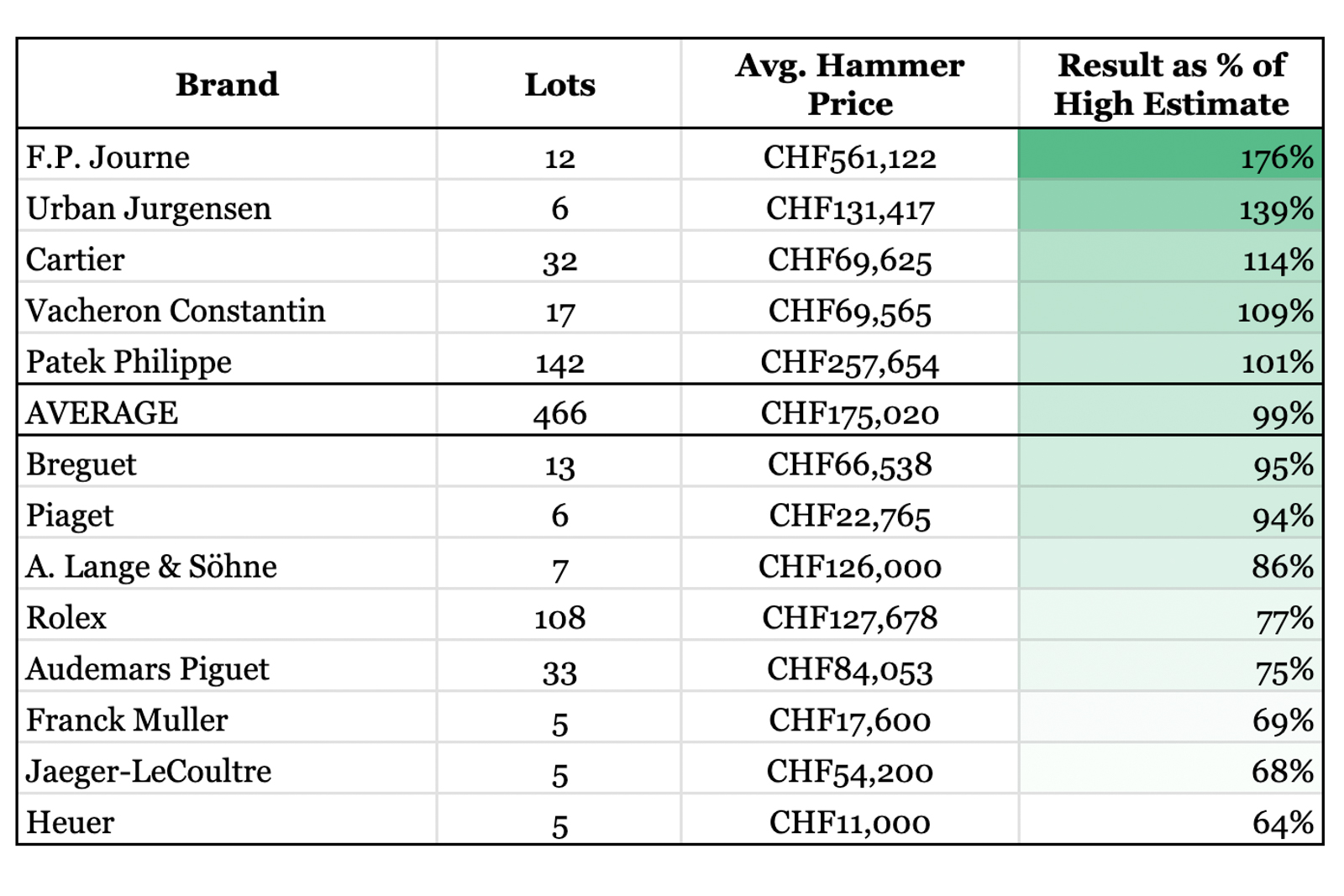

Unpolished measured brand performance by comparing the hammer price to the high estimate, painting a picture of where reality differed from expectations. In short, a handful of brands led by F.P. Journe exceeded estimates, while everyone else came up short. The intense interest in F.P. Journe was one of the major stories of 2025 — the brand was already at the top of the table in 2024, hammering for an average of 146% of the high estimate, but in 2025 this over-performance accelerated further to 176%.

Analysis of the November 2025 Geneva auction season from Unpolished.

The impressive performance of the small number of Urban Jürgensen lots was no doubt an effect of the brand’s successful relaunch last summer, which brought with it renewed interest in the brand’s earlier production. Beyond the boutique brands at the top, big names like Cartier, Vacheron Constantin, and Patek Philippe rounded out the top five. These were the only brands to hammer for more than their high estimates, on average, during the auction season last fall.

Interestingly, while Rolex and Audemars Piguet are among the brands with the best track records for VR according to WatchCharts, they have been underperforming expectations at auction. In the November Geneva auctions, neither brand cracked 80% of their average high estimates, sliding even further from from 2024 when they achieved 88% and 85%, respectively, according to Unpolished.

Inventory accumulation and discontinuation

Several underlying forces shape the secondary market; among them is the continued production of new watches. In each of the last five years, Swiss watchmakers have exported five to six million new mechanical watches, increasing the potential secondary market inventory on a continuous basis. This steady accumulation naturally impacts supply and demand dynamics. So, too, do discontinuations, for the same reasons.

The build up of inventory is one reason for the widening the spread between primary and secondary market prices, but it’s not the only one. Brands also raised prices of new watches by an average of 7% in 2025 according to Morgan Stanley, further widening this gap and increasing collectors’ financial incentive to buy pre-owned.

All eyes on Rolex. Image – Watches & Wonders

In theory, this difference between the new and used price, which according to WatchCharts is currently in excess of 30% for all but the most sought-after brands, should have a chilling effect on sales through primary channels. This can create even more downward pressure on pricing if retailers, stuck with excess inventory, choose to unload it via the grey market.

That said, in reality the watch market rides on emotion, and the bulk of luxury watch buyers still prefer to treat themselves to the retailer experience, even if it means paying a bit more for the privilege. For these buyers, the resale factor is less significant than it is for collectors and enthusiasts, so the effect of inventory build up in secondary channels is mitigated.

Discontinuations can have a more obvious impact on pricing. For example, according to data from WatchCharts, the secondary market prices of certain Rolex references tend to spike in the weeks leading up to Watches & Wonders, as punters speculate on what might get discontinued, in the same way that traders prepare for interest rate cuts.

CPO: a second bite at the apple

Brands that limit themselves to primary channels only have one bite at the apple; secondary market players can derive value from the same watches repeatedly. Case in point, the stainless steel Patek Philippe reference 1518 that Phillips sold last year for more than U$17 million was the same watch the auction house surfaced a decade ago. This same dynamic plays out at lower prices — some of it happens out in the open in online marketplaces and auctions, but much of it happens in private, especially in the form of inter-dealer trades, where the same watch might change hands repeatedly.

While the secondary market has historically been the domain of dealers and auction houses, a handful of forward-thinking brands have developed CPO programmes to take a more active role, and in some cases make some additional revenue from watches made and sold years prior. But it’s also worth noting that the vast majority of brands remain on the sidelines entirely, seemingly content to cede control to others.

Vacheron Constantin is one of the few brands that has invested in building out a CPO programme.

When it comes to CPO, it’s natural to start with Rolex. EveryWatch estimates the number of Rolex watches that changed hands in 2025 at north of 300,000 – nearly a third the brand’s annual production. In fact, the real number is probably much higher when accounting for offline sales not captured by industry data providers.

For most purposes, the actual number is not that important. The precise figure matters less than the scale it implies: by almost any estimate, secondary sales of Rolex exceed the total revenue of most watch companies; this alone makes it significant. In fact, the Rolex CPO programme itself originated from a trend observed in the United States, where Rolex is typically a retailer’s best-selling brand, followed in second place by sales of used Rolex. But for Rolex, getting involved in CPO was not about directly capturing revenue.

During his keynote at Dubai Watch Week, Rolex chief executive Jean-Frédéric Dufour explained that the brand developed its CPO Programme primarily to safeguard its reputation, and ensure that anyone buying a Rolex from an authorised dealer had a selection of serviced and verified watches on hand to choose from. Given the minuscule contribution of CPO fees to the brand’s bottom line, I believe him.

Rolex chief executive Jean-Frédéric Dufour.

The bigger beneficiaries of the Rolex CPO programme are its customers, who now have more and better watches to choose from, and its network of participating dealers, which can maximise the value of their pre-owned inventory, since the CPO designation lifts the value of a watch by much more than the cost of participation. This has enabled some leading dealers like Ahmed Seddiqi to open dedicated Rolex CPO boutiques.

Rolex is not the only brand engaged in CPO, and other brands have developed variations on this model. F.P. Journe has taken the approach of buying back sought-after models in good condition on behalf of its clients, but based on public listings the programme appears limited in scale. To date, most brands have opted for a less capital-intensive, retailer-centric model similar to that of Rolex.

The Ahmed Sediqqi Rolex CPO boutique in Dubai. Image – Ahmed Sediqqi

Closing thoughts

The impressive size and increasing professionalisation of the secondary market play an increasingly important role in the overall watch industry. Directionally, most market size estimates point up and to the right. This growth story has drawn numerous players off the sidelines, from data-driven marketplaces and enthusiast-oriented auction websites to brands’ own dedicated CPO programmes. But the growth picture masks uneven results that favour the incumbents already at the top of the table. From this data, a few conclusions can be drawn.

First, CPO programmes are still somewhat novel, but within a few years not having one may come to be seen as negligent. Brands that ignore CPO are effectively letting dealers and auction houses set the narrative around their products. It’s less about directly capturing revenue, and more about increasing the chance that a customer will have a good experience finding the watch they want in a condition that the brand can stand behind, whether the watch was made in 2025 or 2005.

For brands that primarily distribute through a network of retailers, a CPO programme provides another way to support those dealer relationships and stand out from rivals in a crowded multi-brand boutique setting.

Second, the winner-take-all dynamic may be self-correcting given enough time. It remains to be seen whether the lofty valuations achieved by select references have further headroom for growth, but when a handful of watches account for a disproportionate share of value, it creates an opportunity for contrarian buyers.

The Lange situation is a case in point — a brand with strong collector credibility and fast sell-through times trading at a discount to retail. That’s arguably the definition of a market inefficiency, and inefficiencies tend to get corrected. Of course, being too early is the same as being wrong and Keynes would point out that the market can remain irrational longer than any collector can stay solvent.

Finally, emotion is unpredictable, and it cuts both ways. Many of today’s winners were available at a discount to retail at one time, and some of the biggest declines in 2025 weighed on the darlings of 2021 and 2022. In short, in a market fueled by emotion, looking smart tomorrow takes a little bit of luck today.

Back to top.