Every great collection is a reflection of its owner. In the case of Thomas Engel (1927-2015), the imprint is unmistakable; the mind of an inventor, the discipline of a scientist, and the independence of a man who built his fortune by intuition and sheer will.

Engel lived through war, displacement, and postwar scarcity, only to reinvent himself in the 1950s as a pioneer of polymer chemistry. By the time he turned to horology, he had already registered more than a hundred patents, licensed his inventions to multinational firms, and been hailed as a ‘modern Edison.’

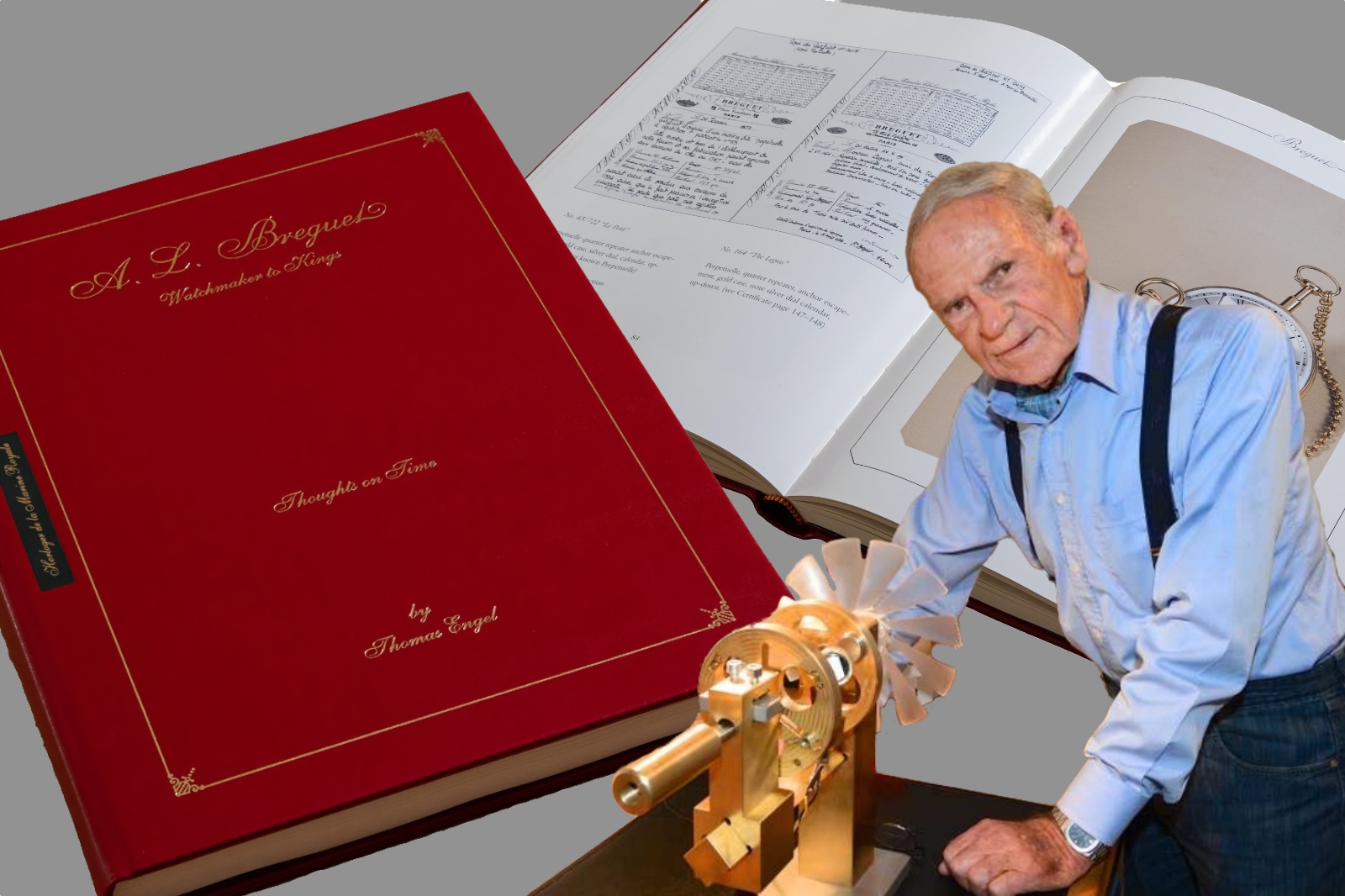

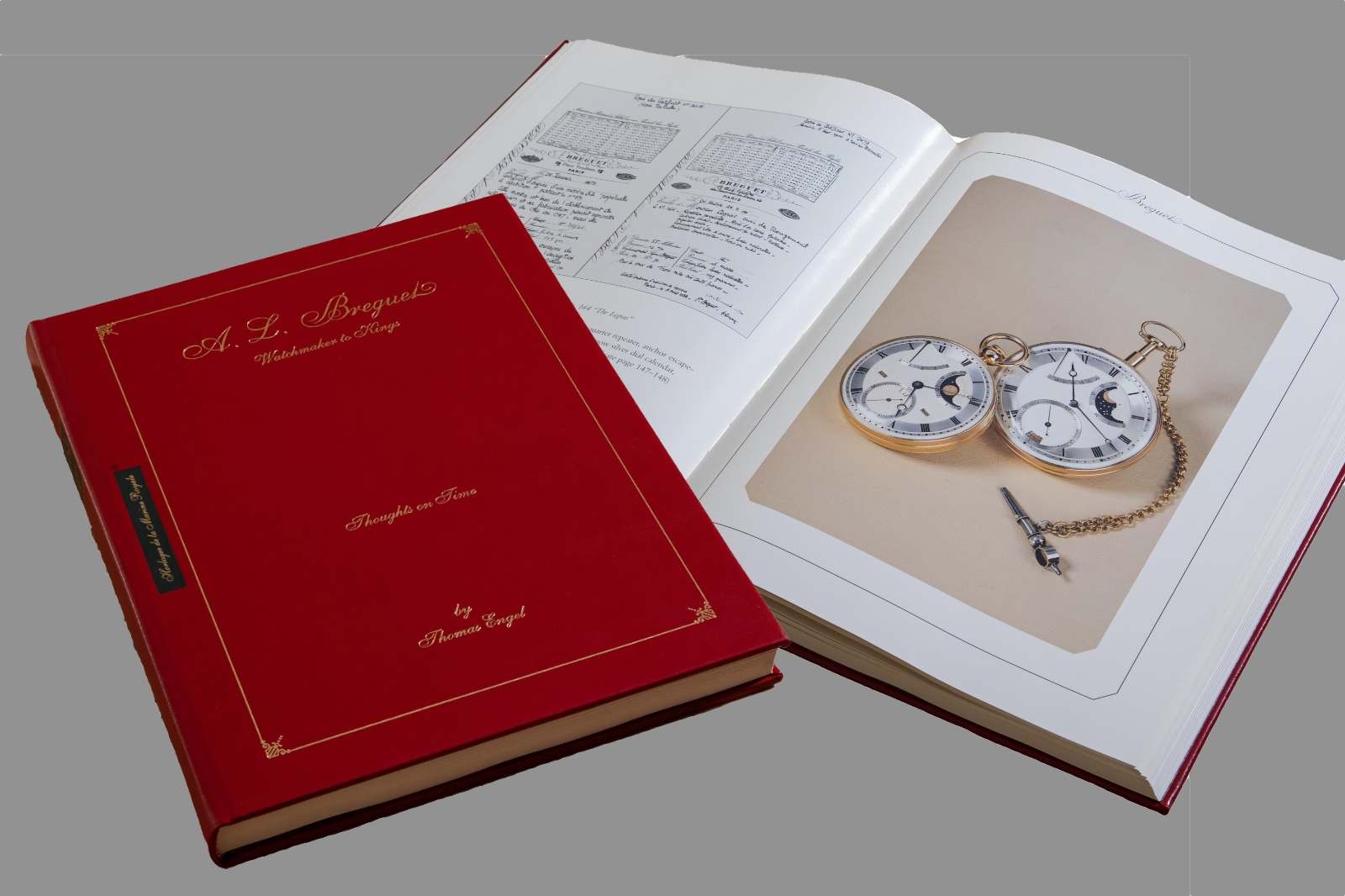

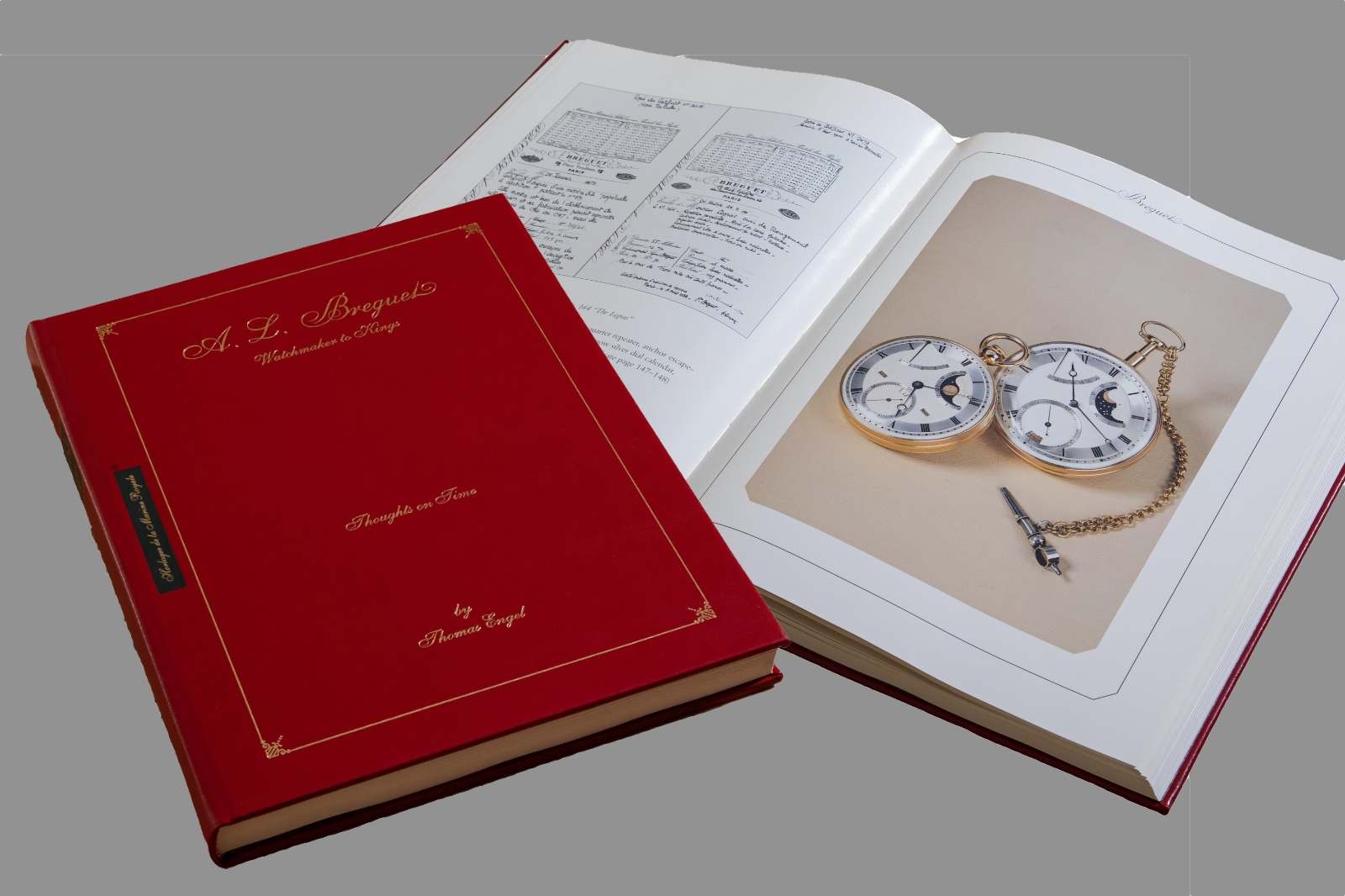

The story that follows is drawn from Engel’s own accounts, above all his two books — Breguet: Thoughts on Time and Ein Moderner Thomas Edison — which preserve his memories, methods, and reflections. They allow his voice to guide the narrative, from his earliest mistakes to his most celebrated acquisitions, and from his inventions in plastics to his interpretation of Abraham-Louis Breguet’s works.

Engel brought to collecting the same qualities that had defined his scientific career: a commitment to verification, a reliance on systematic method, and an instinct for invention. Each watch he acquired was studied as an instrument, its mechanism understood and its history traced. To hold a Breguet, for Engel, was to engage in dialogue with a fellow inventor across centuries.

The man

Thomas Paul Engel was born in Leipzig in 1927, amid the uneasy calm between wars. His father, a textile merchant dealing in fine English fabrics, died when Thomas was only two. Guided by his mother, the family moved from Braunlage in the Harz mountains to Düsseldorf and eventually to Offenbach near Frankfurt, where they lived under the protection of her brother, a bank director. These early dislocations, set against the wider upheavals of Germany’s collapse and reconstruction, nurtured in Engel a resilience that marked every stage of his life.

His childhood was marked by small acts of ingenuity. In Düsseldorf he collected sheep dung, selling it to florists as fertiliser. On the family balcony he raised pigeons, which he sold and bartered. He learned early that survival required improvisation, trade, and imagination. These modest schemes foreshadowed the entrepreneurial reflexes that later brought him wealth.

Thomas Engel and his wife Sylvie. Image – Thomas Engel

The war cut short his education. At thirteen, he was drafted as a Luftwaffenhelfer, an auxiliary for the air force. He quickly shifted to the Marine branch of the Hitler Youth, where he learned rowing, navigation, and seamanship. In his memoirs he recalls these years without romance, a time of privation, fear, and interrupted schooling, where books were scarce and hunger constant. Yet they taught him self-reliance, the ability to read situations, and the discipline of working under pressure.

The immediate postwar years were austere. In Ein Moderner Thomas Edison, Engel recalled: “Only twelve years ago, I was a modestly paid pharmaceuticals salesman and English–German translator. Today, I am a millionaire.” His path to fortune grew from libraries, where curiosity and persistence became the foundation of discovery.

The turning point came in 1958, almost by accident. He noticed that plastic-coated buckets in a Frankfurt shop sold for the equivalent of $10 apiece, an astonishing sum for such a simple object. Instead of dismissing the mystery, he went to the Amerika Haus library and borrowed every book on plastics.

Night after night he studied, teaching himself polymer chemistry from scratch. Within months he had absorbed enough to begin experimenting. His autodidactic method became his trademark: immerse in sources, extract principles, test them through thought and trial, then reduce them to practice.

By 1969, Engel had registered sixty patents in polymer technology. His specialisation was cross-linked polyethylene (PEX), a strong but flexible material now widely used in residential piping. He licensed his “peroxide method” for producing PEX-A to 45 international companies, and it is still in use today. International Management magazine profiled him that year as a “one-man thinking machine.” Each patent earned licensing fees in the tens of thousands of dollars, and within a decade Engel was independently wealthy.

His independence became legend. Corporations courted him with offers of permanent employment, but he refused. “The risks may be greater working alone, but so are the advantages. I like the freedom I have, and I can earn more this way.” He lived in Heusenstamm on a 15,000 square-metre estate that had once been a potato field, building a bungalow with adjoining laboratory, gardens, a swimming pool, and, most dramatically, a heliport. He trained as a pilot, logging over a thousand accident-free hours before reluctantly selling his helicopter when time no longer allowed him to fly safely.

Recognition soon followed. In 1972 Engel received the Rudolf-Diesel Medal for invention at the same ceremony that honoured Wernher von Braun. He was later made an honorary Freeman of the City of London and an honorary member of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, distinctions seldom granted to a German entrepreneur.

Journalists described him as a modern Edison, a title he welcomed. He declared in Ein Moderner Thomas Edison: “It is often said the days of a Thomas A. Edison are past, but they aren’t. A basic idea can generally be traced to a single man. That is a credo of mine.”

This creed framed his life. He believed invention thrived through the vision of individuals willing to risk failure. He treated mistakes as essential steps in the cycle of discovery. That philosophy, born with pigeons in wartime Germany, strengthened in the Amerika Haus library, and rewarded through patents and wealth, later shaped his path as a collector.

When he turned to watches, he approached them as he had polymers, as problems to be solved, systems to be understood, and inventions to be preserved.

The collector: the first lesson

Engel’s path into collecting began by chance, through business. On a London trip in the early 1960s he was seeking contacts for his new plastics process, hoping to secure licensing agreements. One of the men he met was Cyril Rosedale, a bachelor and discreet English gentleman with a quiet reputation as a connoisseur.

Their conversation turned unexpectedly to watches. Engel, fresh with success in industry, confessed that he had just bought a pocket watch signed Breguet from a shop in town. Rosedale examined it and delivered the verdict without hesitation. “That is no Breguet,” he said. “It is a Jura watch, made long after Breguet’s time. The signature means nothing. Breguet’s work is always marked by simplicity, never by ostentation.”

Stung, Engel listened as Rosedale produced a cigar box from his cabinet. Inside lay genuine Breguets, each with provenance. He handed Engel one once owned by Jérôme Bonaparte, sold in 1809 for 3,200 francs. The difference was immediate; the balance of the dial, the restrained elegance, the hidden signature beneath the twelve. For Engel, the revelation was decisive.

That evening Rosedale invited him to his home, White Lodge, a Georgian estate outside London. A butler led Engel through a hall with a sweeping staircase and ancestral portraits, into a library where longcase clocks stood against the walls and trays of watches were set by the fire.

Rosedale sat in his armchair, two dogs at his feet and a spaniel on his lap, and allowed Engel to handle them one by one: repeaters, tact watches, tourbillons. Engel recalled, “One was more beautiful than the other… I could not get enough of looking at them.”

White Lodge revealed collecting as scholarship. The firelit library, the atmosphere of continuity, the quiet authority of Rosedale, all showed Engel that ownership required study, and that true authenticity rested in documentation as much as design. Rosedale explained that almost every Breguet could be verified in the Maison’s ledgers in Paris, and that certificates were issued directly from those records.

Engel left White Lodge transformed. He had entered as an industrialist curious about watches; he departed as a pupil beginning an education. Before he left, Rosedale offered a piece of guidance: “Go to Sotheby’s. Speak with Tina Miller. She will guide you.”

The Zurich connection

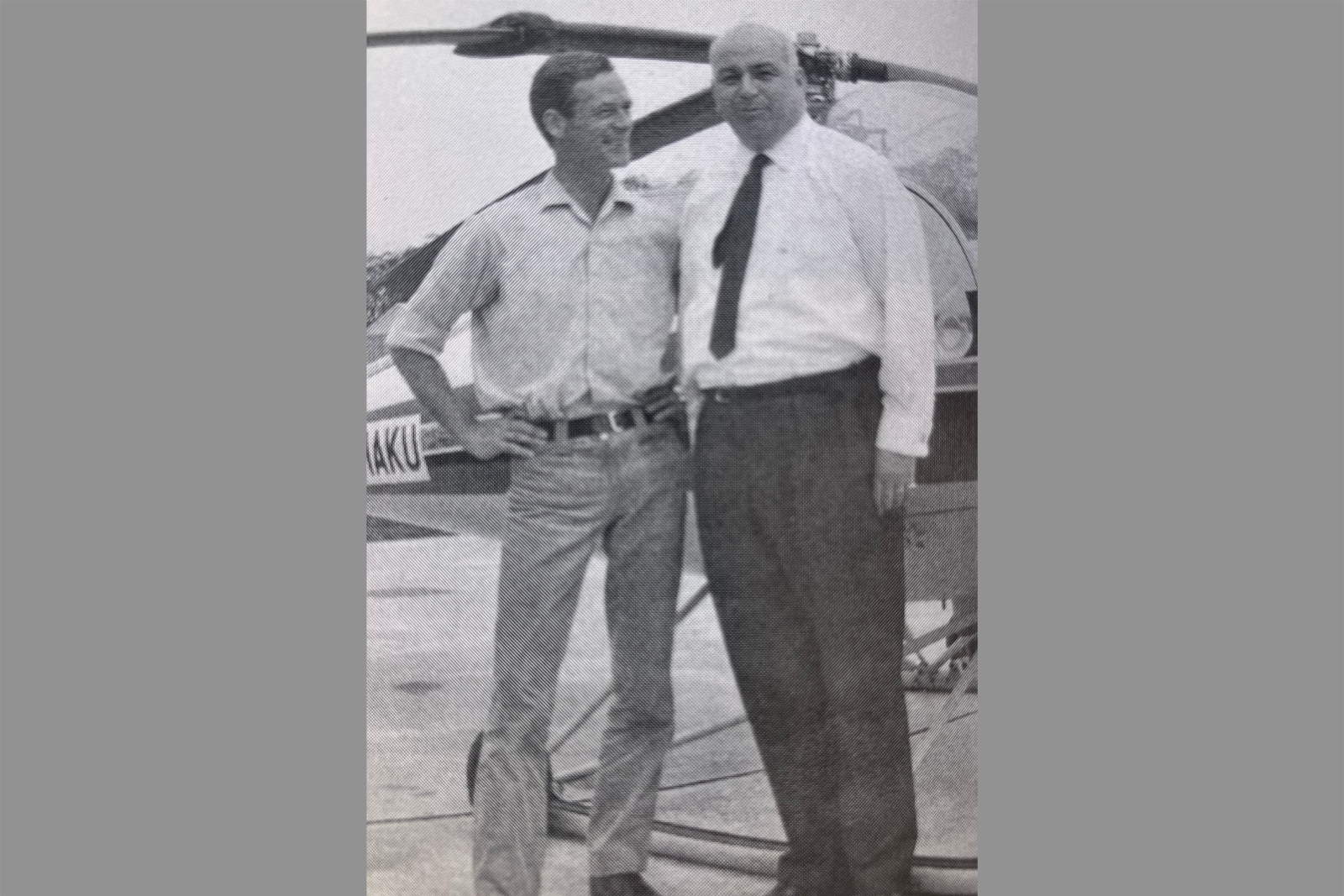

From London, Engel’s path soon led to Zurich. There he was introduced to Edgar Mannheimer, a dealer whose stock of Breguets was matched by his personality. He lived at Sonneggstrasse 22, a white Cadillac convertible often parked outside.

Inside, the flat smelled of garlic and sauerkraut, with paintings leaning against the walls and porcelain crowding the tables. Mannheimer himself was broad, heavyset, and wore a small black cap. He had survived two years in concentration camps and carried himself with bluntness and humour.

Thomas Engel and Edgar Mannheimer. Image – Thomas Engel

Engel’s first major purchase from him set the tone for their relationship: a red-gold Breguet from 1798, with Turkish numerals, sold originally to a caliph in Constantinople. It came with a certificate, verifiable provenance, and the secret signature beneath the twelve. “From the first moment I knew it was a Breguet,” Engel later wrote.

The relationship grew into friendship. Mannheimer and his wife Janet often visited Engel’s estate in Heusenstamm, arriving with suitcases full of watches. They shared meals and stories; Edgar spoke of the camps in his thick Bohemian-Jewish dialect. Years later, when he was dying, Janet telephoned Engel, telling him her husband wanted to see him one last time.

In the auction room Mannheimer became indispensable. Engel disliked drawing attention, so the two devised a discreet method: a nudge of the knee under the table signalled that he wanted to bid, and Mannheimer raised the paddle. Dealers knew Edgar’s reputation and rarely pressed against him. Engel valued this shield, which allowed him to buy boldly without being seen.

For Engel, Mannheimer was much more than a dealer; he was a partner and confidant. “Without him,” he admitted, “many of the watches would never have come my way.”

The Sotheby’s education

Following Rosedale’s advice, Engel introduced himself to Tina Miller at Sotheby’s. When he asked about Breguets, she replied “We have the next auction in two months, but there is no Breguet in it. That can still change, one never knows. I will gladly send you the catalogue.” For Engel it was the beginning of a friendship that lasted years.

Miller often telephoned him directly when important Breguets appeared, sometimes before they reached the catalogue. As he noted in Ein Moderner Thomas Edison: “I could always rely on her advice, especially when it came to judging the quality of a watch.”

His first great success came with a Breguet described as “in almost new condition, with chain, key, and the original case with certificate signed by Louis Breguet himself.”

Rosedale had seen it too. “I wanted to buy it myself,” he told Engel, “but if you are interested, I will step back.” Engel acquired it, grateful not only for the watch but for the generosity of his mentor.

The jumping seconds

One afternoon the telephone rang in Heusenstamm. It was Tina Miller. “Tom, we have a highly interesting Breguet that just came in. You should come and have a look.”

When Engel arrived in London, she showed him a marvel: a watch with a jumping central seconds, the hand leaping once each second like a station clock. “The special thing was that the second hand stopped between each beat, so one could make very precise measurements of time.” Built in 1808, it had been sold to a Russian count. Its condition was pristine, consigned by an English couple who wished to donate the proceeds to a children’s home.

The auction was fierce. The British Museum bid against him, determined to secure it. Engel held steady, finally winning at 76,000 Deutschmarks. Engel later remembered Tina Miller telling him, “Tom, you’re totally crazy. You just bid against the British Museum.”

Later she traced its provenance back to a Christie’s sale in 1920, when it had been imported from Russia and sold for 112 guineas. For Engel, the discovery confirmed that every watch carried a biography, and each acquisition required research to uncover it.

The Spanish queen’s watch

Another drama unfolded in Germany. A young man inherited a watch from his father, a naval officer. When he took it to a watchmaker, the case was weighed and valued at 350 Deutschmarks, the price of the gold. The watchmaker hesitated, and advised “There may be collectors who would enjoy this watch. Put it into an auction, you may receive more.”

The catalogue entry was spare: “A gold pocket watch with red enamel inlays, signed Breguet, in need of repair.”

Bidding began at 800 Deutschmarks and climbed rapidly. Within minutes the hall reached 100,000 Deutschmarks. The young seller grew pale. Past 150,000 Deutschmarks, the increments slowed. At 300,000 Deutschmarks the hammer fell. The room erupted in applause, first tentative, then unanimous.

The next day newspapers carried the headline: Record price for a pocket watch. Research revealed it had been made for Queen Maria Cristina of Spain, wife of Ferdinand VII. Mannheimer had secured it for Engel, who recorded it simply in Ein Moderner Thomas Edison: “Today this watch is part of my collection.”

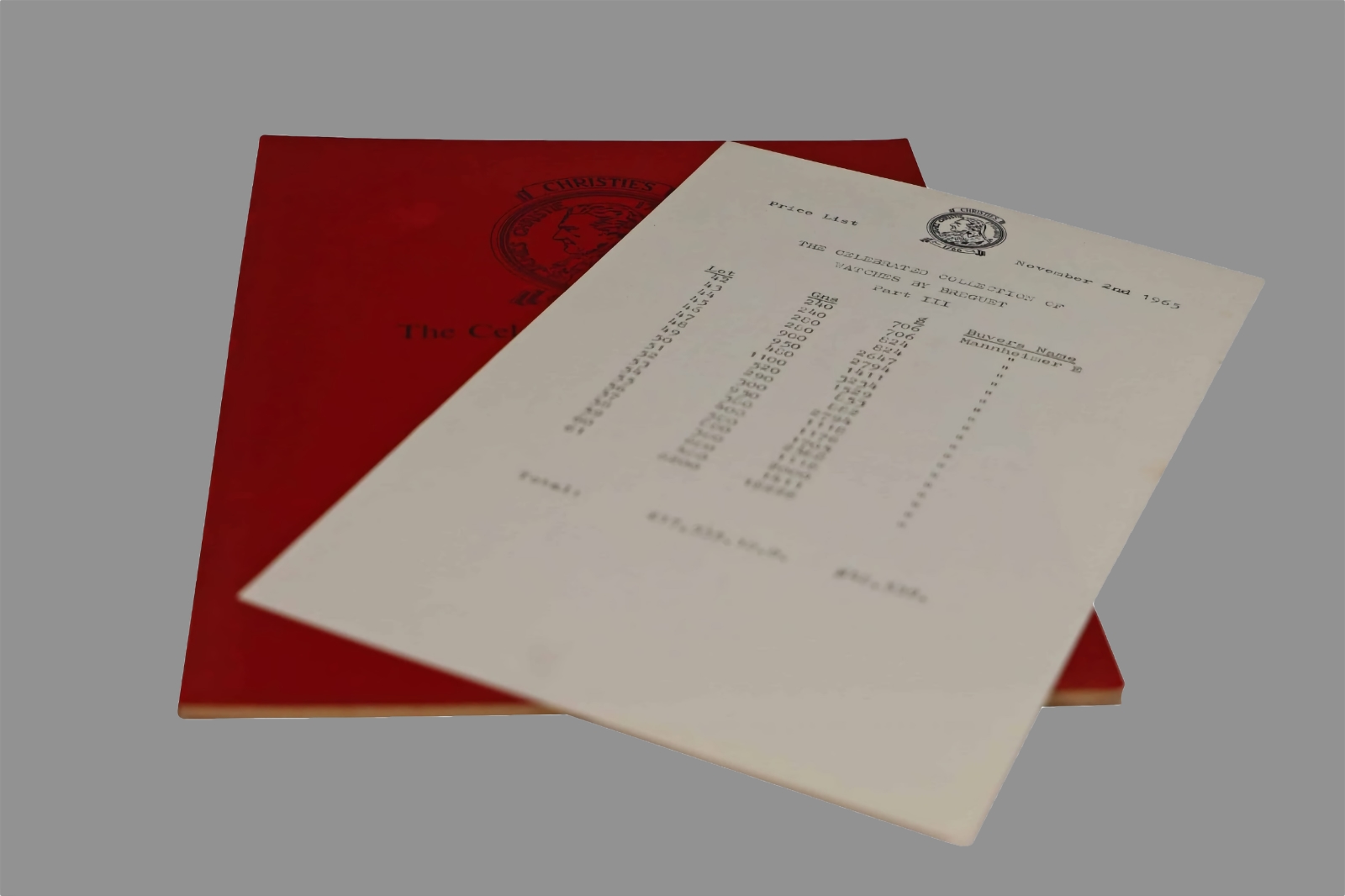

The Salomons collection

The greatest opportunity came with the sale of the Sir David Salomons Collection at Christie’s, a landmark in the history of Breguet collecting. One evening Richard Faulkner telephoned: “We have some Breguet watches that just came in yesterday for the next auction. You should come and have a look.”

In the basement vault Engel was shown trays of envelopes, each containing a Breguet with its certificate. “After two hours I had seen all the watches and yet understood none… On the certificates were names like Tsar Alexander I, Napoleon Bonaparte, Alexander von Humboldt, King of Prussia. It was overwhelming. I was simply speechless.”

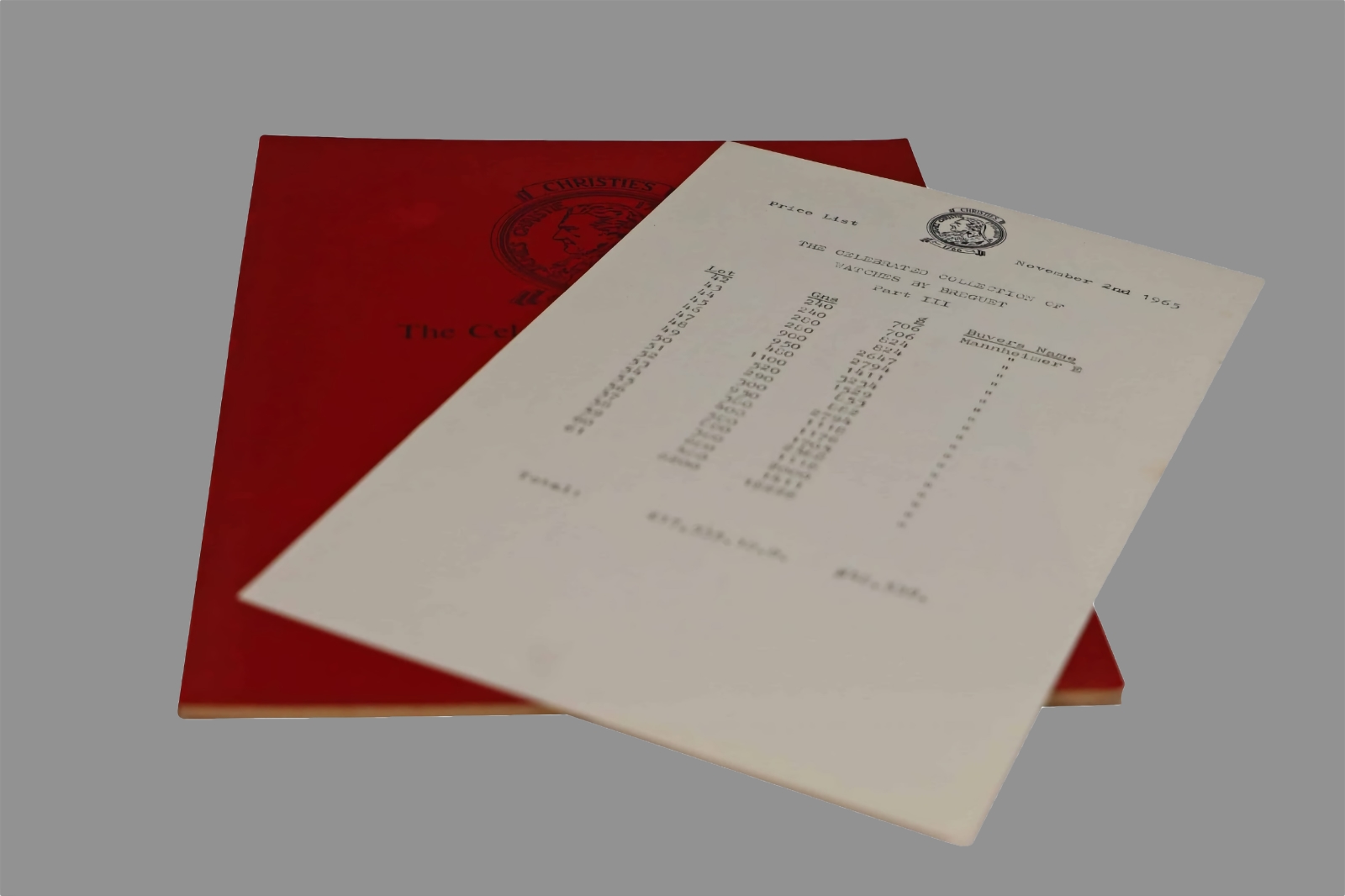

Christie’s 1965 final Salomons sale catalogue. Image – private archive

Christie’s divided the collection into three sales. In the first two, Engel bought selectively through Mannheimer. At the second, Napoleon’s watch appeared, but the price soared too high. Engel learned that the most famous pieces carried premiums that distorted the market.

By the third sale, conditions had shifted. It was a rainy London day, the room half empty, the market saturated. Engel had spent the night at White Lodge, taking counsel from Rosedale. At Christie’s he met Mannheimer and agreed on their signal: a nudge of the knee.

Lot after lot passed; Mannheimer raised his paddle at each nudge. Within minutes they had secured ten watches in a row. A rival tried to resist, but Engel pressed harder, and Mannheimer answered every bid. By the end they had taken the entire catalogue.

British newspaper The Times reported, “Yesterday a dealer from Zurich bought all remaining Breguet watches from the Sir David Salomons Collection. It is rare in the history of auctions that a client purchases an entire catalogue.”

That evening Engel returned to White Lodge, where he and Rosedale divided the watches by the fire. Engel later reflected, “In the following years… they increased tenfold in value. I call that well invested compared to bank recommendations.”

The Halpern affair and the coin toss

The next great adventure came on the advice of George Henri Brown, director of Breguet in Paris. Brown told Engel of a physician in New York, Dr. Halpern, who owned 15 Breguets, each preserved in original red leather cases with certificates. “It is a unique group,” Brown said. “You should go and see them.”

Engel telephoned Halpern, and after tough negotiations they agreed on a price for the collection. With the deal settled in principle, Engel travelled to New York carrying a bank cheque for one million dollars, ready to conclude what promised to be the most important purchase of his life.

At Halpern’s home the watches were laid out for inspection. At first sight the array dazzled: gold cases, complications of every type, and certificates to match. Engel examined each carefully with his loupe. He was prepared to hand over the cheque on the spot. At that moment, Halpern hesitated. Together with his wife he declared that they could not part with the watches after all. The agreed sale was withdrawn, and Engel was left holding his cheque, powerless to complete the deal.

As consolation, Halpern offered him one watch. Engel later recounted how Halpern told him, “This piece is probably not genuine. It does not appear in the archives. You can have it for a thousand dollars.” Engel examined it closely. It was a small gold watch with quarter repeater and calendar, dating from around 1780, earlier than the surviving ledgers. To him it was unmistakably a true Breguet. He accepted the offer, paid the modest sum, and returned to Europe with a single piece instead of a collection.

Seth Glanville Atwood. Image – Rockford Register Star

Two weeks later, while dining with Edgar Mannheimer in Zurich, the telephone rang. On the line was Seth Atwood, the Chicago banker and founder of the Time Museum. Atwood explained that he was in negotiations to buy a collection of 15 Breguets in New York, but had been told by the seller that a German collector had already offered more.

Mannheimer laughed, “That German collector is sitting right next to me.” Engel took the receiver, explained the situation, and proposed a solution: “Proceed with the purchase, and we will divide the watches between us.” Atwood agreed.

Mannheimer flew to New York, Atwood arrived by private jet from Chicago, and the two met in a hotel room to divide the spoils. To ensure fairness Mannheimer suggested they toss a coin to see who could choose first.

He produced one, and flipped it. The coin rolled across the carpet and disappeared beneath the bed. Both men dropped to the floor, laughing as they retrieved it side by side. The toss came out in Engel’s favour. Guided by his instructions, Mannheimer chose almost all the pieces Engel desired.

When he returned to Frankfurt, unshaven and exhausted, Mannheimer told Engel, “Tom, if you ever have another adventure like this, you can call me anytime, day or night.”

The story became legend among collectors. Engel always remembered the Halpern affair as an episode of paradox and theatre: he had travelled to New York with a million-dollar cheque for 15 watches, yet came home with one bought for a thousand.

Through Atwood and Mannheimer, however, he eventually secured the best of the group. For Engel the lesson was enduring — in collecting, knowledge, trust, and improvisation mattered as much as money.

The collection

Thomas Engel regarded his watches as instruments of invention, each a solved problem rendered in steel, gold, and enamel. His cataloguing reflected his life as a scientist: precise measurements, complete provenance, detailed notes on repair history. He regarded his collection as an archive, a working laboratory in which Breguet’s genius could be studied across generations.

Tourbillons: perfection in motion

Among all inventions, Engel reserved special admiration for the tourbillon. It united Breguet’s search for accuracy with mechanical poetry.

Breguet 1809 No. 1176, the Comte Potocky. Image – collage

Breguet No. 1176, the “Comte Potocky”, delivered in 1809 for 4,600 francs, was one of Engel’s touchstones. It housed a four-minute tourbillon with échappement naturel, twin subsidiary seconds, and a stop-seconds lever that froze time for precise setting.

The dial design of this watch will likely become much more well known, as it was recently revisited for the Classique ref. 7225, released to mark the brand’s 250th anniversary.

Engel described its inverted fusee and dual escape wheels with the same clarity he once applied to polymer chains. He delighted in the measured rotation of the carriage, one turn every four minutes, and its natural lift escapement designed for minimal friction.

Breguet No. 2568, the Moltshatwff (left). Image – Thomas Engel collection

Equally prized was No. 2568, the Moltshatwff, a one-minute tourbillon with two secret signatures. It had belonged to Sir David Salomons, who bought it in 1923 for £35. When it reappeared at Christie’s in 1965, it fetched 6,200 guineas.

Engel enjoyed retelling the story: how a watch bought for the price of a good suit in the 1920s had become worth thousands within a generation. For him, it was a case study in how knowledge, rarity, and provenance combined to create value.

Complications with history

Engel was drawn to Breguet’s complications, where mechanical ambition and history intersected. Breguet No. 2077, the King of Spain, was a grande sonnerie with minute repeater, encased in gold with translucent red enamel. Engel marvelled at the coexistence of such fragile artistry with one of horology’s most demanding mechanisms.

Breguet No. 2077, the King of Spain. Image – collage

No. 53, the Orloff, was an astronomical watch with moon phases. It fascinated Engel because its history traced the rhythms of the resale market. First sold to Monsieur Hawley of London, it passed to Prince Orloff, and later reappeared in Paris. Engel copied each transfer from the ledgers into his notes, intrigued that even in Breguet’s lifetime his watches circulated like artworks, traded and retraded among the powerful.

Breguet No. 53, the Orloff. Image – collage

Touching the past

The tact watches, designed to tell time by touch, had particular charm for Engel.

Breguet No. 689/1861, the Lucien Bonaparte. Image – collage

No. 689/1861, the Lucien Bonaparte, had passed through Breguet’s hands four times. Engel traced its resales, from Bonaparte’s secretary to later owners, noting that Breguet himself often bought watches back to place them anew. To Engel, this showed the master as market maker, anticipating the secondary market long before Sotheby’s or Christie’s.

Breguet No. 2292, the Labouchere. Image – collage

No. 2292, the Labouchere, with its grey translucent enamel and pearl touchpieces, embodied discretion and elegance. Engel described it as a philosophical gesture: a watch created to be felt as much as seen. In an age of visual display, he admired its quiet subtlety.

The democratic masterpieces

Engel gave equal respect to the souscription watches, simple single-hand pieces built to broaden Breguet’s clientele. He saw in them a different kind of genius: the ability to democratise excellence.

Breguet No. 3624, the Demidoff (right). Image – Thomas Engel collection

No. 3624, the Demidoff, with its clear dial and single hand, embodied this principle. In Breguet: Thoughts on Time, Engel wrote: “Its construction is so clear and logical that repairs can be done even by less experienced watchmakers.

The souscription ranges within the most ingenious work of Breguet. A masterpiece, indeed.” Where others saw “entry level,” Engel recognised like-minded pragmatic ambition.

Garde-temps: the biography of instruments

The garde-temps chronometers appealed directly to Engel’s scientific temperament. They represented the meeting point between Breguet’s engineering genius and the empirical habits of the laboratory. Built for accuracy, these watches embodied the ideals that had guided Engel’s own work in polymer research: controlled variables, stable conditions, and repeatable performance.

He regarded them as field instruments, each one a self-contained experiment in precision timekeeping. Their austere beauty spoke to him more than enamel or engraving, because it reflected a watchmaker’s understanding of physical law translated into metal.

Breguet No. 153/4570, the Pozzo di Borgo. Image – collage

No. 153/4570, the Pozzo di Borgo, carried parachute protection on both pivots, a pivoted detent escapement, and a service record as layered as a human biography. Engel noted each entry: repairs in 1829, 1830, 1834; an accident in 1847; further overhauls in 1852 and 1857. To him, these records affirmed a life lived in measurement, an instrument that had accompanied generations through work, failure, and renewal.

Philosophy through objects

What united Engel’s collection was coherence. He insisted on documentation, condition, and provenance. He celebrated invention, valued clarity over decoration, and approached collecting as interpretation. He observed in Breguet: Thoughts on Time: “Every Breguet is a problem solved.”

His watches spanned the full spectrum: souscriptions for merchants, tact watches for princes, tourbillons for aristocrats, garde-temps for scientists. Each was chosen to illustrate a chapter in Breguet’s story.

For Engel, the watches stood as teaching instruments, conversation partners, and case studies in ingenuity. His collection formed a museum in miniature and a diary at once, recording the encounter of a twentieth-century inventor with an eighteenth-century genius on common ground.

The collector becomes a creator

Engel’s journey as a collector eventually led him to sign a few watches of his own. After years of studying Breguet’s ledgers, examining escapements, and tracing provenance, he wished to move from interpretation into creation.

He collaborated with Swiss watchmaker Richard Daners, whose tourbillon carriages powered many of the modeller Engel-signed watches, and partnered with Zenith to build movements or source observatory-grade chronometer calibres for his limited editions.

Thomas Engel No. 6, ca 1980. Image – collage

These pieces expressed Engel’s philosophy. Some carried traditional complications, one-minute tourbillons, regulators with power reserve, moon-phases and thermometer indicators, while others offered simpler layouts reflecting his preference for clarity and proportion.

Each was constructed to the standards he applied in his collecting: full documentation, carefully selected movements, and discrete yet precise execution. For Engel, signing a watch was symbolic: it closed the circle between invention, collection and creation. Just as his patents had left their mark on materials science, these watches embodied his belief that the study of horology could lead naturally into practice.

Today, the Engel-signed watches appear occasionally at auction, rare reminders of a collector who sought not only to be custodian and interpreter of Breguet, but to join the ranks of the maker.

Method man

Thomas Engel approached collecting with the same precision he applied in his laboratory. The mistake in London sharpened his eye, and from then on he pursued authentication as a discipline.

He developed a method that followed a clear sequence. Every candidate Breguet was checked against the brand’s ledgers in Paris, the thick leather-bound volumes recording each sale with date, buyer, and price. Engel cultivated access to these archives, working closely with staff such as Emmanuel Breguet, who welcomed him as both client and researcher.

He then examined the watch itself: dial signatures, the secret sous le XII engraving visible only under magnification, the geometry of escapements, the quality of steelwork. Provenance came next: certificates, auction records, correspondence with earlier owners. Engel worked like a forensic scientist, convinced that truth resided in details often missed by casual eyes, a hinge placement, a screw head, or the frustoconical oil reservoir drilled into a wheel tooth.

This method gave him confidence to share his views with others. As Engel remembered, dealers in Paris would tell him, “Times are too restless, people trust watches more than money or stocks. Paintings can be forged, but watches with documents endure.” Engel agreed, and emphasised that the finest pieces, fully documented, could serve as enduring investments.

To illustrate the point he often cited the tourbillon No. 2568: bought by Sir David Salomons for £35 in 1923, resold in the 1960s for more than £5,000. For Engel, that growth reflected how scholarship and rarity together shaped value.

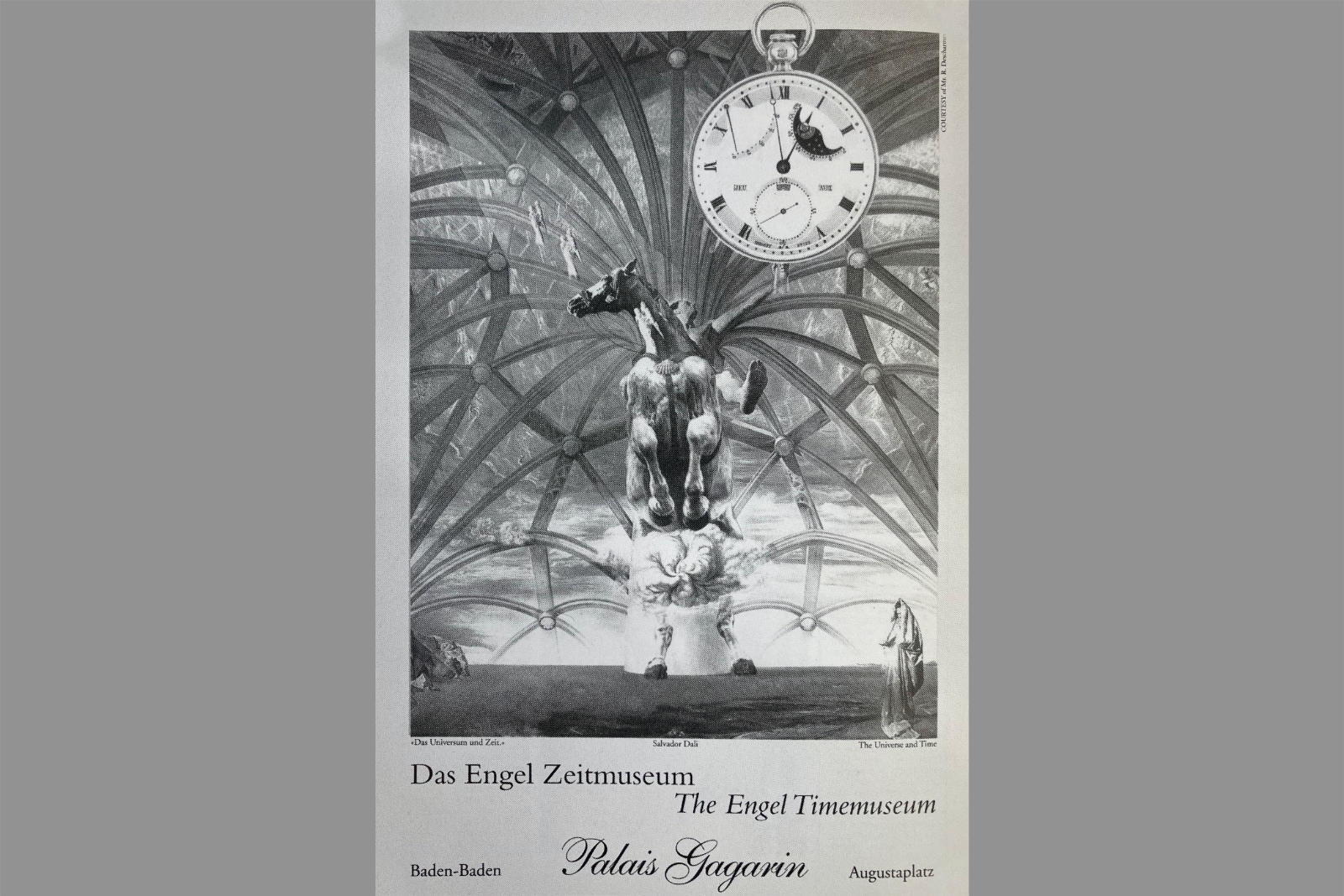

The museum that never was

At the height of his collecting, Engel planned to establish a museum in Germany devoted to Breguet. His intention was to offer the public a permanent place where invention could be experienced directly through original works. A site near Frankfurt was proposed, designs circulated, and newspapers reported on the project. Officials welcomed the idea and spoke of cultural significance.

Poster for the museum that never was. Image – Thomas Engel

Progress slowed as bureaucratic processes lengthened and funding commitments dissolved. Despite early enthusiasm, the necessary support failed to materialise. Engel had hoped to create a lasting cultural institution; when the project collapsed, he turned his attention to another form of permanence. If the museum could not be built in stone and glass, it could exist in print.

A legacy of scholarship

From this determination came Breguet: Thoughts on Time, published in 1994 after three decades of work. The book was part catalogue, part biography, part meditation. Each watch in his collection was described with technical specifications, provenance, and market history.

He explained escapements with the clarity he brought to his patents in plastics: the overhanging ruby cylinder that reduced friction, the oil reservoirs cut into anchor wheel teeth to prolong lubrication.

Thomas Engel´s Breguet book “Thoughts on Time”

The book carried a philosophical dimension. Engel compared Breguet to Stradivarius, concluding that while Stradivarius had perfected, Breguet had invented. Invention, to him, reshaped the possibilities of an art. His declaration “One cannot improve on a Breguet” became his credo and entered the vocabulary of collectors.

The reception was immediate. Dealers cited his research in catalogues. Antiquorum and Christie’s began listing provenance and technical notes with greater precision, echoing the standards he had demonstrated. Collectors used the book as reference; scholars relied on it as a bridge between connoisseurship and history.

Antiquorum founder Osvaldo Patrizzi later observed that Engel’s meticulousness influenced Antiquorum’s catalogue style, pushing it toward greater scholarly depth. Engel took quiet pride in the result. Pleased that he had created something lasting, he noted in Ein Moderner Thomas Edison: “The book became very sought after.”

By the time Engel’s collection dispersed, his legacy was secure. The watches moved into new hands, yet the standards he set remained. He showed that a collector could be custodian, interpreter, and scholar. His greatest invention was not a polymer process or a plastics patent. It was a way of collecting: rigorous, methodical, and enduring.

Conclusion

Thomas Engel’s story is that of a man who refused to accept limits. He emerged from war and scarcity with little formal education, yet taught himself a science, patented over a hundred processes, and became a millionaire inventor.

He then carried the same independence and curiosity into horology, turning a beginner’s mistake into the foundation of one of the finest private Breguet collections of the twentieth century.

What distinguished him was consistency. Whether designing polymers or evaluating a tourbillon, he trusted method over appearances, proof over assertion. He cultivated friendships with scholars and dealers, built trust in auction rooms, and insisted that every watch be read as both mechanism and document. In doing so, he raised standards across the collecting world, showing that scholarship and connoisseurship belonged together.

Engel collected to interpret, to trace invention, to understand markets, and to preserve memory. His book Breguet: Thoughts on Time distilled that philosophy into a form that outlasted his own collection, ensuring that what he assembled would continue to educate long after it was dispersed.

The watches themselves began new lives. Some entered museums, such as the tact watch No. 987 “Prince Russe” and No. 2782 “Hervey” at the Musée International d’Horlogerie, or No. 1320 “Constantinople” in the Montres Breguet collection.

Others resurfaced at major auctions: the grande sonnerie No. 2077, once made for the King of Spain, sold at Dr. Crott in 1980; the Comte Potocky tourbillon No. 1176 and the Moltshanoff No. 2568 drew fierce bidding at Antiquorum Geneva in 2001; and No. 47, the “Lord Spencer,” reappeared at Christie’s Geneva in 2017, carrying with it a link to Winston Churchill. Many remain in private hands, their whereabouts unknown but their identities secure through Engel’s meticulous documentation.

In Engel’s life, invention and collecting converged. Both were driven by curiosity, guided by discipline, and shaped by the search for solutions that endure. His legacy lives in the watches he assembled, in the standards he set for their study, and in the journeys those pieces continue to make through collections worldwide.

Thomas Engel died in 2015, leaving behind a life defined by invention and interpretation. His patents transformed materials science, his scholarship deepened the history of horology, and his standards continue to guide collectors and institutions. He stands as a model of the inventor-collector, a man who transformed personal passion into lasting cultural contribution.

Back to top.