The Forgotten Boston Collector Who Rivalled Henry Graves Jr.

Elliot Cabot Lee and his pocket watch collection.

Between 1885 and 1920, Elliot Cabot Lee (1854-1920) quietly built one of the world’s largest collections of very complicated watches, but unlike the famous rivals Henry Graves Jr. or James Ward Packard, both of whom favoured Swiss watches (and primarily Patek Philippe), Lee was a devotee of English watchmaking during its heyday.

Many remarkable watches that were commissioned by Lee, or passed through his collection, have surfaced over the last few years, such as the J.W. Benson Supercomplication, the Dent Astronomical watch, or even J.P. Morgan’s pocket-planetarium, but with their provenance unknown.

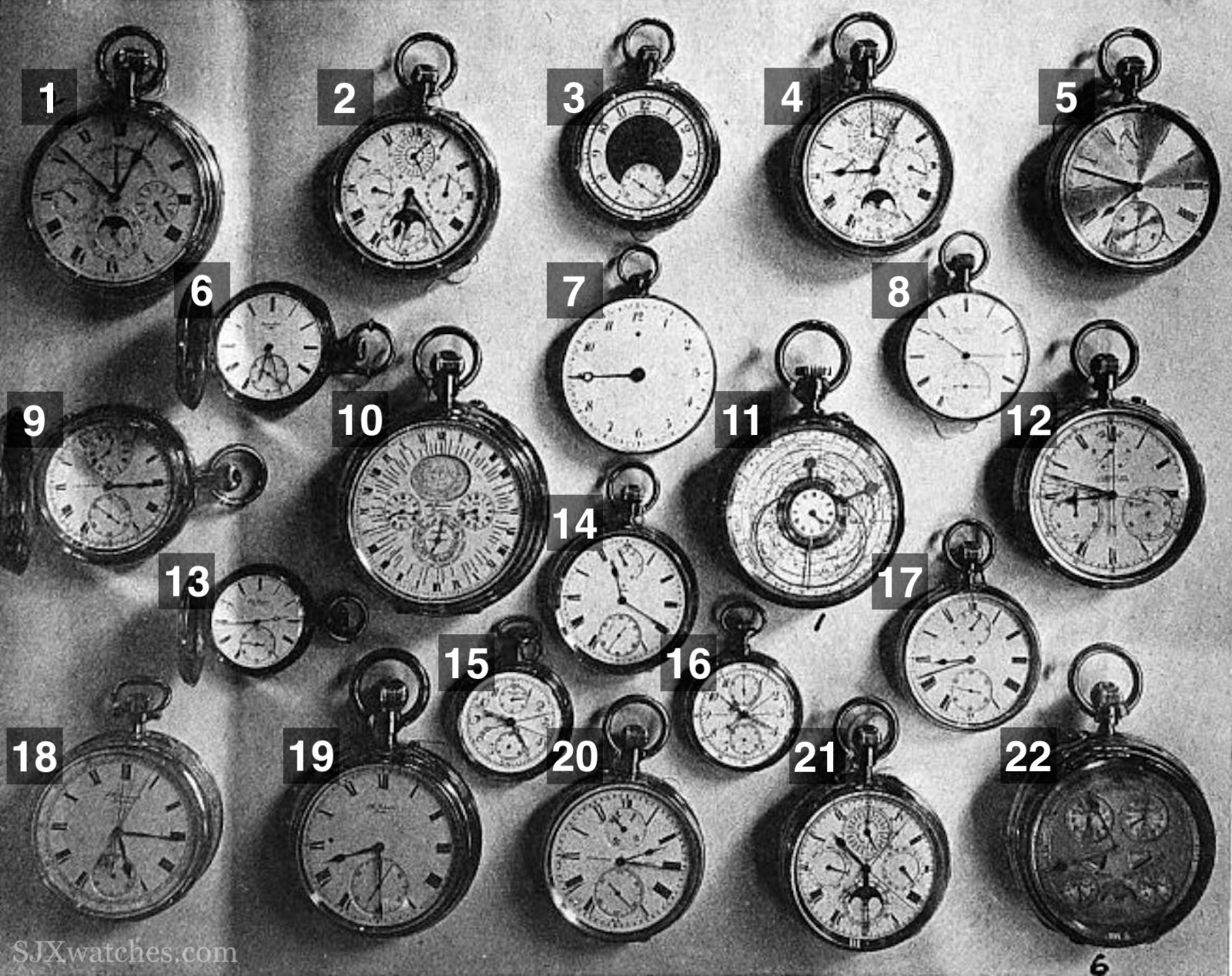

Most of Lee’s collection of pocket watches. Image – The National Jeweler 1922

A patrician collector

Elliot Cabot Lee was born on April 16th, 1854 in Brookline, Massachusetts. Both of Lee’s parents hailed from Boston Brahmin families and were third cousins. His father, Henry Lee Jr., was a partner at investment bank Lee, Higginson & Company, where Lee also worked, though only briefly. His mother, Elizabeth Perkins Cabot, was the granddaughter of the extremely wealthy Thomas Handasyd Perkins – a slaver turned philanthropist.

Lee graduated from Harvard with a law degree and passed the bar, though he seems to have practiced law little if at all. He was well-travelled and well-read, accumulating a notable book collection, according to the Brookline Historical society.

Besides his watch collection, Lee also took an interest in the nascent automobile. He built a garage, or an “automobile stable” as it was called at the time, on the Perkins Estate inherited from his mother’s family, and was involved in the Phelps and Shawmut motor companies according to volume 18 of The Automobile. In 1905, Lee’s peers elected him president of the American Automobile Association (AAA) as reported by American Motorist.

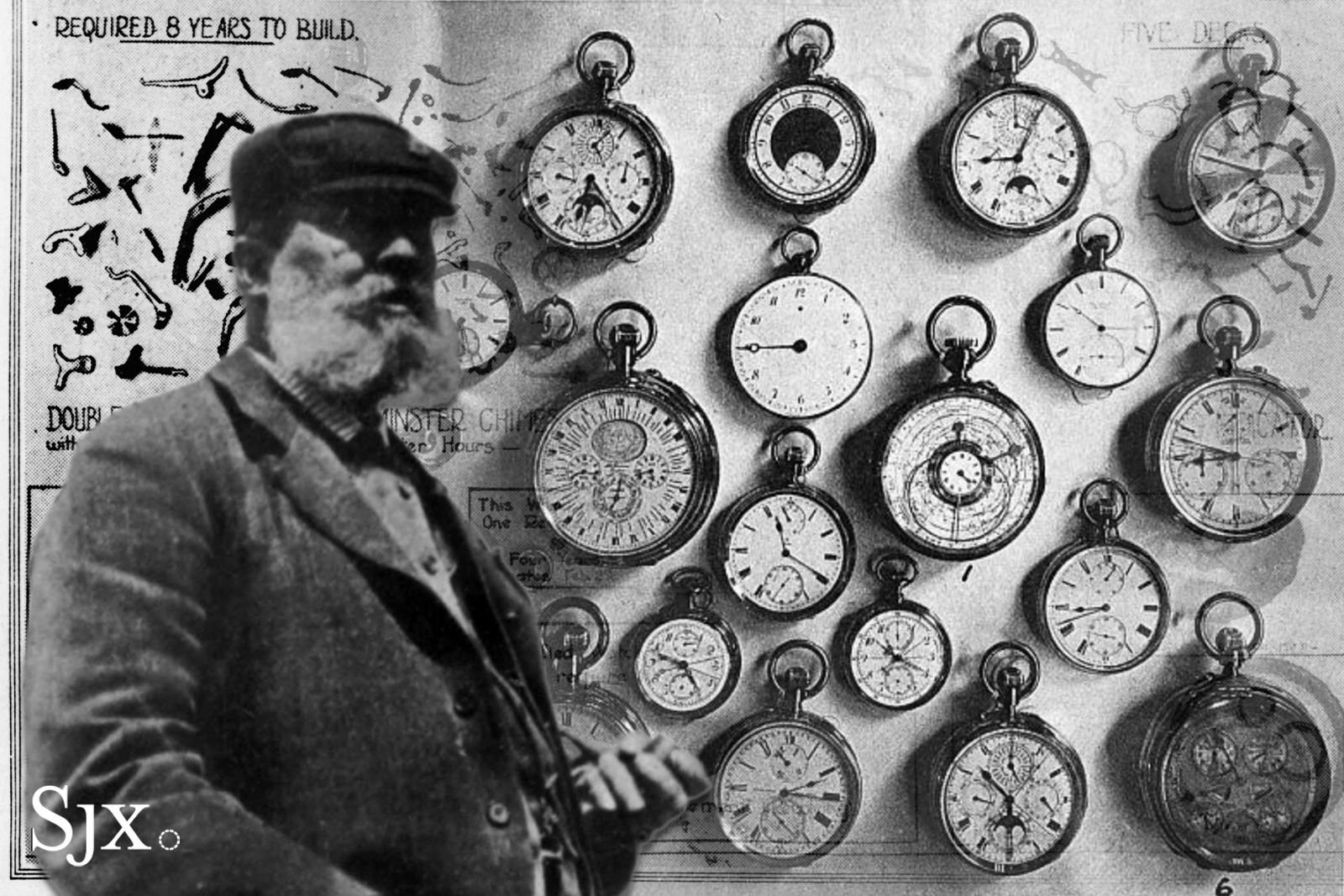

Elliot C. Lee. Images – American Motorist 1912, The Automobile January 1904

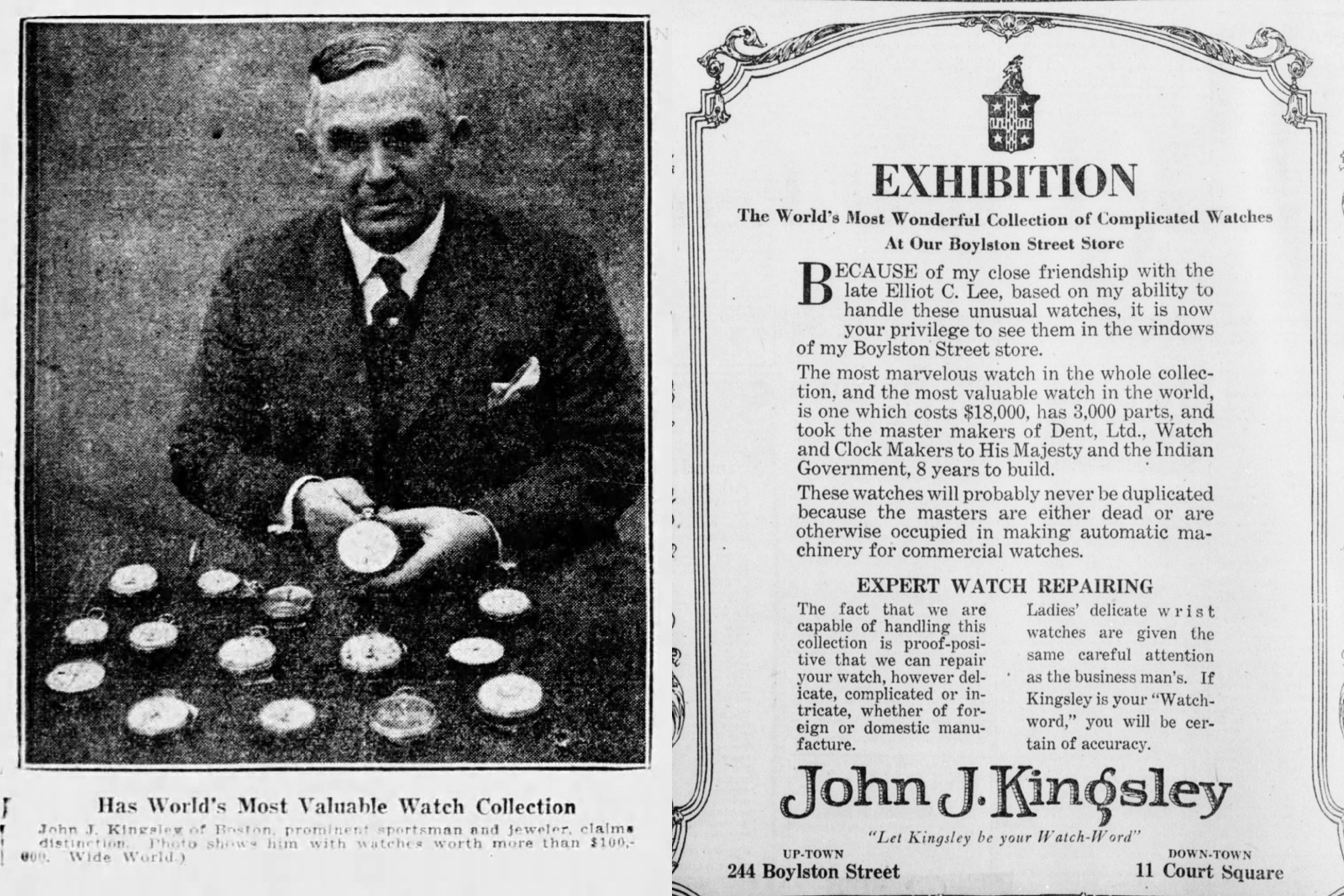

Most of what we know of the collection comes from John J. Kingsley of Boston, a watch retailer, watchmaker and friend, to whom Lee entrusted his collection. Both men were AAA members, and Kingsley aided Lee in planning his commissions. Kingsley kept the collection on display in his Boylston Street store for a time in 1924 according to an advertisement in The Boston Traveler newspaper and brought a selection of Lee’s watches from Massachusetts to James Ward Packard’s home in Ohio for his private viewing, as mentioned by Stacy Perman in A Grand Complication, a book about the ostensible rivalry between Graves and Packard.

Lee’s collection included clocks as well, one of which, a baroque German astronomical clock, is on display at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Kingsley said that Lee was in the habit of gifting watches from his collection to others.

What sort of watches did Lee prune from the collection? The only one I managed to track down was a pocket chronometer with tourbillon, spring detent escapement and fusee signed by Victor Kullberg sold by Christie’s in 1999. The late Reinhard Meis depicts this watch on page 229 of Das Tourbillon.

Advertisement for the exhibition of Lee’s collection. Images – The Boston Traveler. March 13, 1924 J.J. Kingsley with the collection, The Springfield Daily Republican March 6, 1924

Lee was known to carry multiple watches at once and was rarely seen twice with the same, according to Kingsley. An anecdote in volume seven of The Automobile Magazine affirms this: “It used to be a regular performance in the old days to casually ask Mr Lee if he had the time. This was usually followed by his consulting a watch the like of which you were sure never to have seen before. Questioning the accuracy of the timepiece, while it brought a pained expression to Mr Lee’s face, was quickly followed by his bringing forth another equally unique time-teller as proof that the first one told only the truth. I never saw the occasion when Mr. Lee couldn’t produce these proofs in quantity sufficient to convince any doubter, and I never saw him produce the same watches when on some other day the same performance was gone through with.”

His obsession with accuracy led to the installation of a regulator clock in his home, mounted on brickwork – probably best as old New England houses tend to sway due to construction and weather.

The Perkins Estate. Image – Massachusetts Historical Commission 1983

Lee never married and didn’t stay in the same place long enough to. He spent at least five (non-continuous) years in Europe and one in Asia; within the United States he moved from Massachusetts to Florida, to California, to Massachusetts again and finally to North Carolina, where he died in February 1920.

While in Massachusetts, he lived with his sister Elizabeth and her family in an apartment on the Perkins estate. The Gentleman Mr Shattuck, a biography of Lee’s nephew, mentions that Lee “carried innumerable watches on his person, and [the] children loved to come up to him and ask: ‘what time is it [in Paris] Mr Lee?’ and he would whip out a watch and say: ‘six o’clock.”

Lee never children of his own but remained in close personal relationships with his nieces and nephews in their adult lives.

The commissioner-collector

Nearly all of Lee’s watches were from the major English firms, such as Dent, Smith, Benson, and Player, though with the notable absence of Frodsham. The English approach to watchmaking deviated from the Swiss style that is dominant today.

English watchmakers did not waste time on bevelling, striping, or perlage and instead let acid do most of the work for them. Monolithic, gilt, three-quarter plates were the most characteristic feature of English watchmaking. Jewels were often set into flush gold or brass bushes, rather than being rubbed into the bridges directly. Incidentally, English labour was much more expensive than Swiss.

Watch 1: S. Smith & Son 304-1. Image – Antiquorum

Good English watches typically used free-sprung balances (vanishingly rare in Swiss pocket watches) and diamond end stones for the balance (a practice the Swiss reserved for only simple, very high-grade watches). The English had their own detached lever escapement, now known as the English lever, which used a pointed (usually brass) escape wheel instead of the club-foot profile used in the Swiss lever.

They also disagreed with the Swiss on what constitutes a chronometer. The Swiss would tell say it’s based on performance – any watch can be a chronometer if it passes an independent test of its precision. The English would have said that a chronometer must use a chronometer (detent) escapement, which was usually paired with a helical balance spring and free-sprung compensation balance. Many of Lee’s watches were chronometers by both English and Swiss reckoning.

Watch 3: Dent 33’139. Image – Sotheby’s

English watches trended larger than their continental counterparts and more often included chronometry-focused features such as the spring detent escapement, revolving escapements (tourbillons and karrusels), chain and fusee and up/down indicator. The English were eager to combine these features with complications, which the Swiss were loath to do.

Watch 21, Dent No. 32’274 features a semi-helical hairspring and diamond a endstone for the rattrapante.

That said, by the turn of the century, complicated English watches were as much Swiss as they were English. Essentially, all chiming complications originated from the Vallee de Joux, with many passing through Capt & Cie.’s workshop in Le Solliat – which was located on the same street as Philippe Dufour’s is today. Even English perpetual calendar and some chronograph works of this period were Swiss – a fact the English houses were cagey about.

The Lee collection contained five extremely complicated double-faced watches: two signed Dent (22, and not shown), one J.W. Benson (10), one J. Player & Son (11), and possibly one S. Smith & Son (not shown). Other complicated watches included an oversized S. Smith & Son clock watch with retrograde perpetual calendar (1), a grand complicated Dent with tourbillon (21, no 32’274) and two other Dent perpetual clock watches (2, likely watch no. 33’581, and 4).

Most of Lee’s watch collection. Image – The National Jeweler 1922

Watch 21, Dent No. 32’274 was one of two Dent tourbillon clock watches owned by Lee. Louis-Elisee Piguet completed the ebauche in 1901.

Lee preferred open-face watches, the only complicated hunter-cased watch being an S. Smith & Son chronograph with hour and minute totalisers and a twelve-minute flying tourbillon (9). It’s notable for being one of the first flying tourbillions and two-button chronographs. The sprung front cover on this watch has been cut and fitted with a crystal, effectively turning it into an open-face watch.

Another chronograph (12) has registers dropped below the centre line, as seen on a few other English watches, including Packard’s. All simple watches with up/down (5, 14, 17, and 20) can be assumed to be tourbillons, karrusels, fusees, or something similar until proven otherwise.

Only two watches (15 and 16) have typical Swiss-styled cases. Watches 6 and 13 can be attributed to Jules Jürgensen based on the distinctive bow. All watches shown are modern, or were at the time; the sole exception being a Breguet Souscription (7), which was already an antique a hundred years ago.

Watch 9: S. Smith & Son 1901-23. Image – Antiquorum

The Dent Astronomical Watch

Dent was amongst the most prestigious English names and widely imitated. Chronometer maker Edward John Dent (1790–1853) went into business with John Arnold’s son, who apprenticed under Abraham-Louis Breguet, in 1830 before striking out on his own ten years later. His firm made the Great Clock of Westminster, colloquially called Big Ben, though he died before completion. Dent’s company also retailed watches, both English and the best Swiss imports.

Dent no. 32’573 (finished around 1904) is the best-documented watch in Lee’s collection, thanks to Daniel Aubert’s research published in the 1988 edition of Chronométrophilia. Dent ordered the movement from Nicole Nielsen, Capt & Cie.’s partner in England and the leading supplier of complicated movements during Lee’s day.

Founded in 1839 as Nicole & Capt, the company later became Nicole, Nielsen & Co. when Danish watchmaker Sophus Emil Nielsen joined as partner around 1870. Besides founding the company, Adolphe Nicole, or one of his employees, invented the modern chronograph, and the rattrapante. George Daniels lauded Nicole Nielsen’s tourbillons in particular as the best a watch can be, and it’s hard to disagree.

Watch 22: Dent no. 32’573. Image – Sotheby’s

The austere enamel front dial belies the engine-turned silver astronomical dial on the back. The 27’’’ movement itself is oversized but otherwise a typical minute repeating clock watch with grande et petite sonnerie on two gongs made from a Swiss ebauche.

Dent sold another double dialled watch, no. 32’545, with the same base movement but with a perpetual calendar with date from the centre on the back. An external regulator is under the bezel of both watches, allowing easy adjustment without removing the rear dial. Other double-dialled watches, such as the Leroy 01, Graves Supercomplication and Star Caliber 2000 make use of similar systems.

Watch 22: Dent no. 32’573, under the front and rear dials. Image – Sotheby’s

The astronomical complications are the work of Leon Aubert, who likely contributed to other watches in the collection as well.

The mechanisms for the times of sunrise and sunset, equation of time, morning and evening stars, and signs of the zodiac connect to the perpetual calendar on the front through the hollow going barrel arbour. Cams program the equation of time, time of sunrise and time of sunset; each cam sits on a wheel that turns once per year, driving their respective hands. The longer, globe-tipped hand completes one revolution each year, acting as an annual calendar and indicating the zodiacs.

Watch 22: Dent no. 32’573, disks and calender plate removed. Image – Sotheby’s

The most unusual of the many esoteric mechanisms are the morning/evening stars, and times of moonrise/moonset. Apertures labelled morning and evening stars show the planets (Mars, Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, or Saturn) that are visible in the sky each morning and evening on polished gold disks. These, along with the phases and age of the moon, are driven separately from the rest of the astronomical indications. A retrograde system with two saw-tooth cams uses one cam for moonrise and the other for moonset.

J.P. Morgan’s Watch

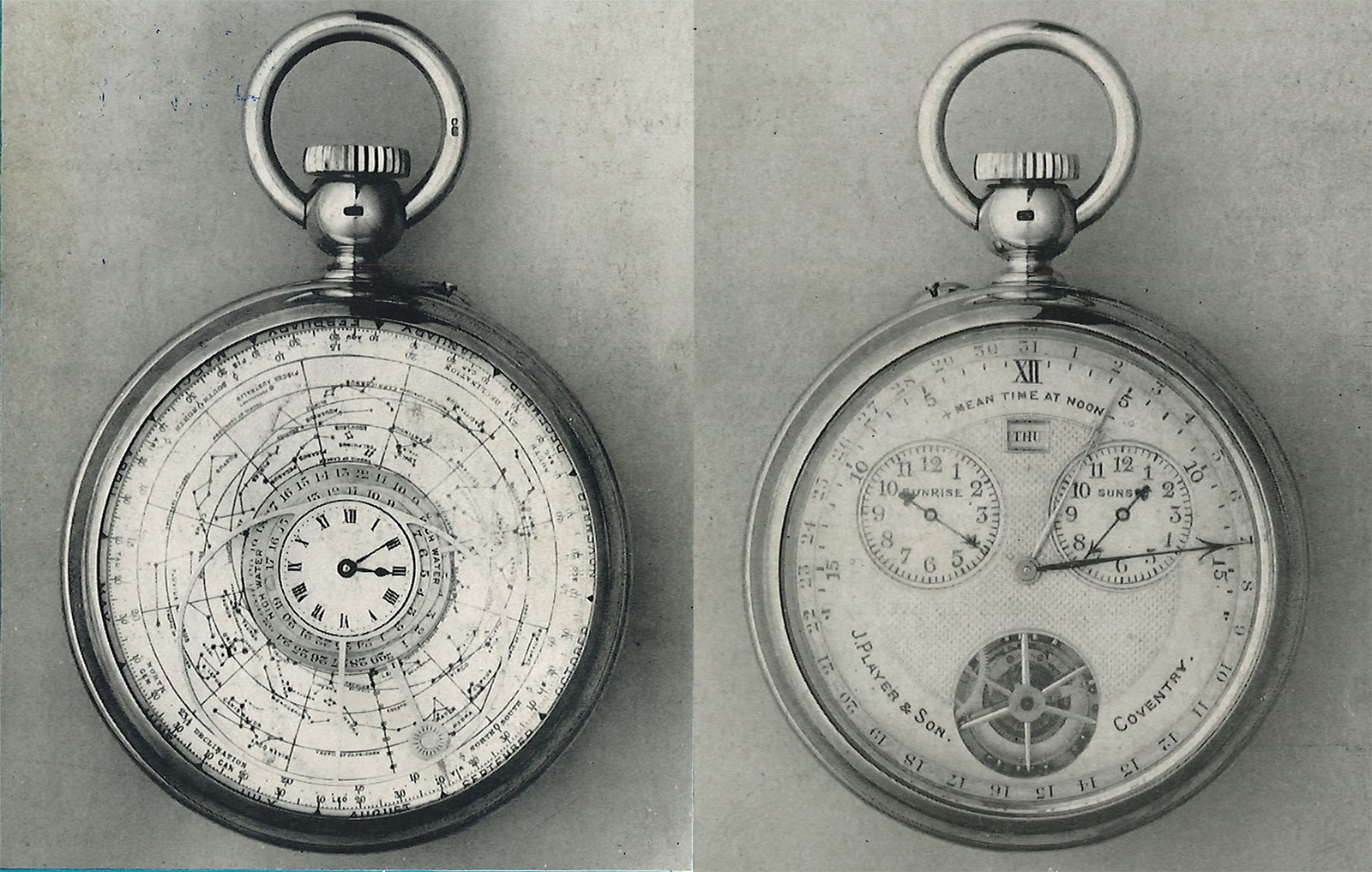

John Piermont Morgan commissioned watch 11, and Lee acquired it after Morgan’s death in 1913. It certainly looks like the type of watch a man so rich he bailed out the US government (twice) would own. J. Player & Son was a Coventry-based watchmaker, a city that was once the heart of the English watch and clock industry. While not as well known as the London-based firms, Player made some exceptional watches, including Morgan’s.

Watch 11: J. Player Astronomical watch. Image – HIA Journal, 1947

The watch is a striking anachronism; at first glance, I would have guessed it to be nearly a hundred years older than its true age. In context, this makes perfect sense as J.P. Morgan mostly collected antique watches and likely owned some of George Margetts’s astronomical watches from the late 1700s, which must have inspired the Player.

George Margetts 312. Image – Sotheby’s

The miniature dial in the centre gives mean solar (conventional) time and supports the mobile elliptical frame that represents the visible sky north of 23 ½ degrees latitude. The silver moon rotates once every 24 hours, 50 minutes and 28 seconds, showing the passage of the moon across the sky and the tides. Below this is a sun hand which turns once every 24 hours; these two disks interact to show the age and phase of the moon.

Finally, the planisphere disk rotates once about every 23 hours, 56 minutes and four seconds – which is one sidereal day. The interaction of this disk with the sun hand shows the solar declination, months of year and zodiacs. The Margetts watch functions similarly.

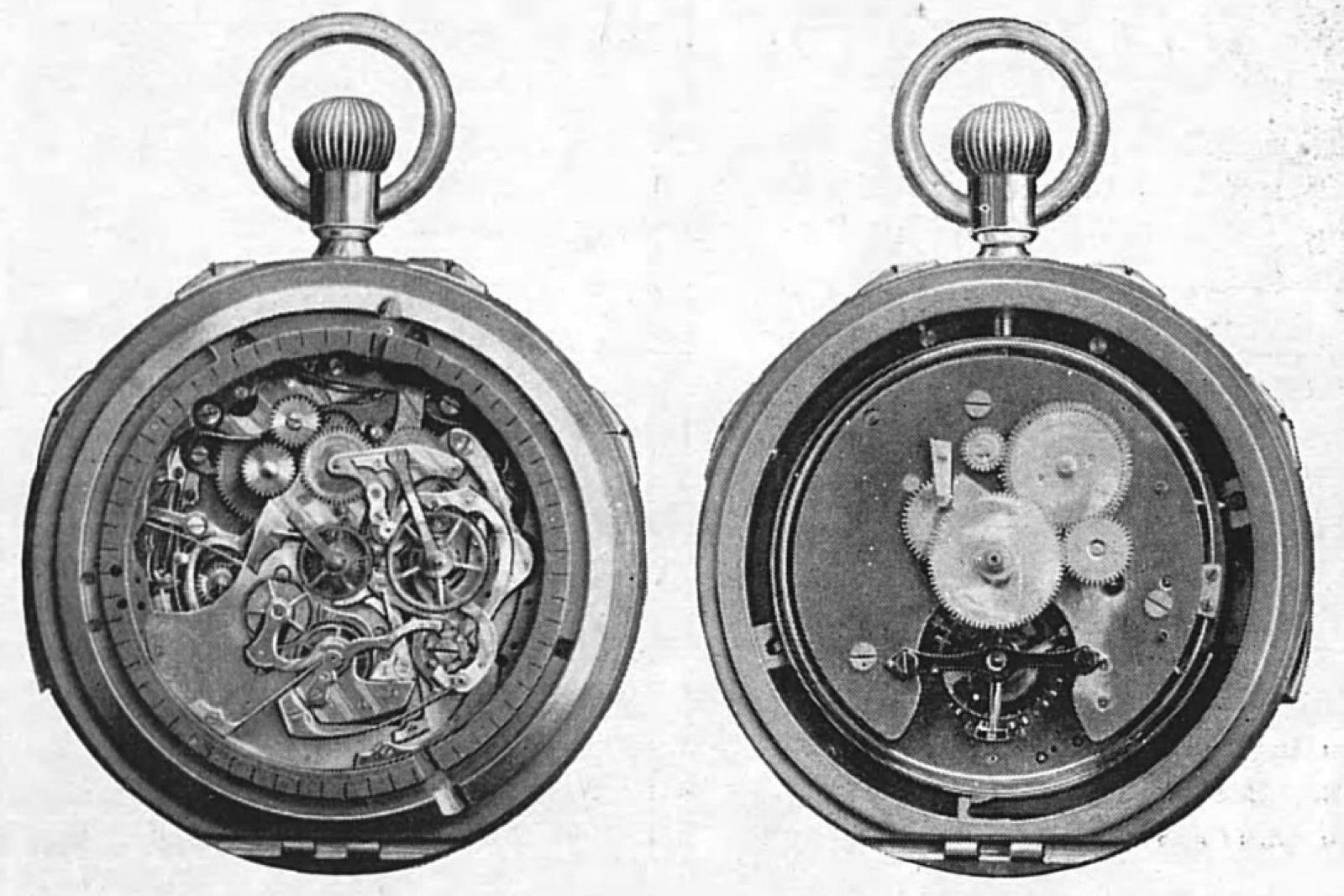

Both side of the movement in Morgan’s watch. Image – Colin Crisford

On the back is an engine-turned dial with a perpetual calendar that indicates the date by hand from the centre, this style of calendar is used in several English watches, including the one made by Dent for James Ward Packard and the S. Smith & Son 309-2 (made from a Louis-Elisee Piguet ebauche).

Besides the date, the calendar tracks weekdays, times of sunrise and sunset, and equation of time. Underneath everything is an oversized grande et petite sonnerie clock watch movement very similar to the one used in the previous Dent. Most notable is the massive tourbillon visible through the dial, the balance alone is larger than some entire movements. While tourbillons are common today, they were rarer and more revered in Lee’s time with only a few highly skilled watchmakers specialising in their construction and adjustment.

The J.W. Benson “supercomplication”

Another of Lee’s watches was a double-dialled “supercomplication” by J.W. Benson. Interestingly, the Benson and Morgan’s J. Player both ended up in the collection of Benjamin Mellenhoff, once the head watchmaker at Tiffany & Co. in New York, but the two watches parted ways after his death.

J.W. Benson was a London-based retailer of jewellery, diamonds, silverware, and other luxury goods. The firm also sold watches and clocks under their own brands, including a relatively large number of complicated watches – even triple and grand complications. Benson claimed to make movements at its Ludgate Hill factory, which may have been true for simple watches, though certainly outsourced complications.

Watch 10: J.W. Benson triple chronograph. Image – Christie’s

On the front is an uncommon triple chronograph, which is likely three chronographs stacked on top of each other, or two stacked chronographs and one rattrapante.

When the crown is pressed all three chronographs engage, when pressed a second time one is stopped, then the second and finally the third. A fifth and final press resets all three chronographs at once. Only the last chronograph has a minute counter. The tachymeter is calibrated for a fourth of a mile. Note this is a dédoublante, not a rattrapante, since the stopped hands cannot be made to catch up to the one still advancing.

Example of a Swiss triple chronograph. Image – Bonhams

Under the bezel is a concealed date, for what is most likely a perpetual calendar, and strike mode selectors for grande sonnerie, petite sonnerie and silence. The watch imitates Westminster chimes and can do so to the minute on demand by using the trip near 4:00. The back is likely also the work of Leon Aubert, with a planisphere showing the sky north of 23 ½ degrees latitude, time of sunrise and sunset, passage of the zodiacs and equation of time. Arrayed across the dial are time offsets of most major cities from Greenwich mean time for easy reference, though I’m sure Lee knew the time off-sets for all these cities by heart.

Unbelievably, watch 18 is also a triple chronograph by J.W. Benson, but lacks a minute counter. This watch uses two stacked chronographs and one rattrapante on the back of the same oversized clock watch movement used in the Dent Astronomical watch. The case is also unusual, with an oblong bow, and engraved case band.

Watch 18. Image – Colin Crisford

Lee’s “supercomplication”, Dent 36’544

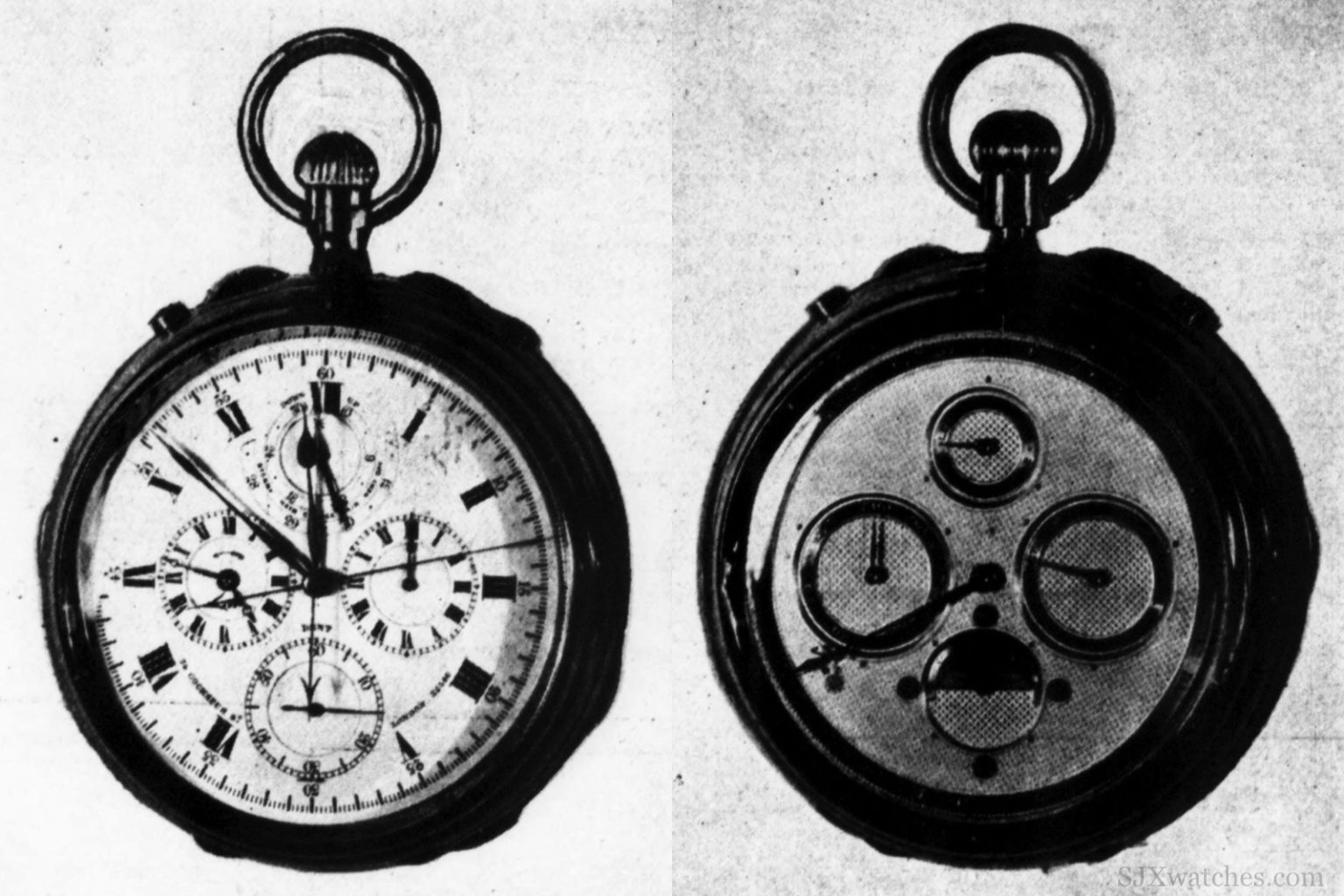

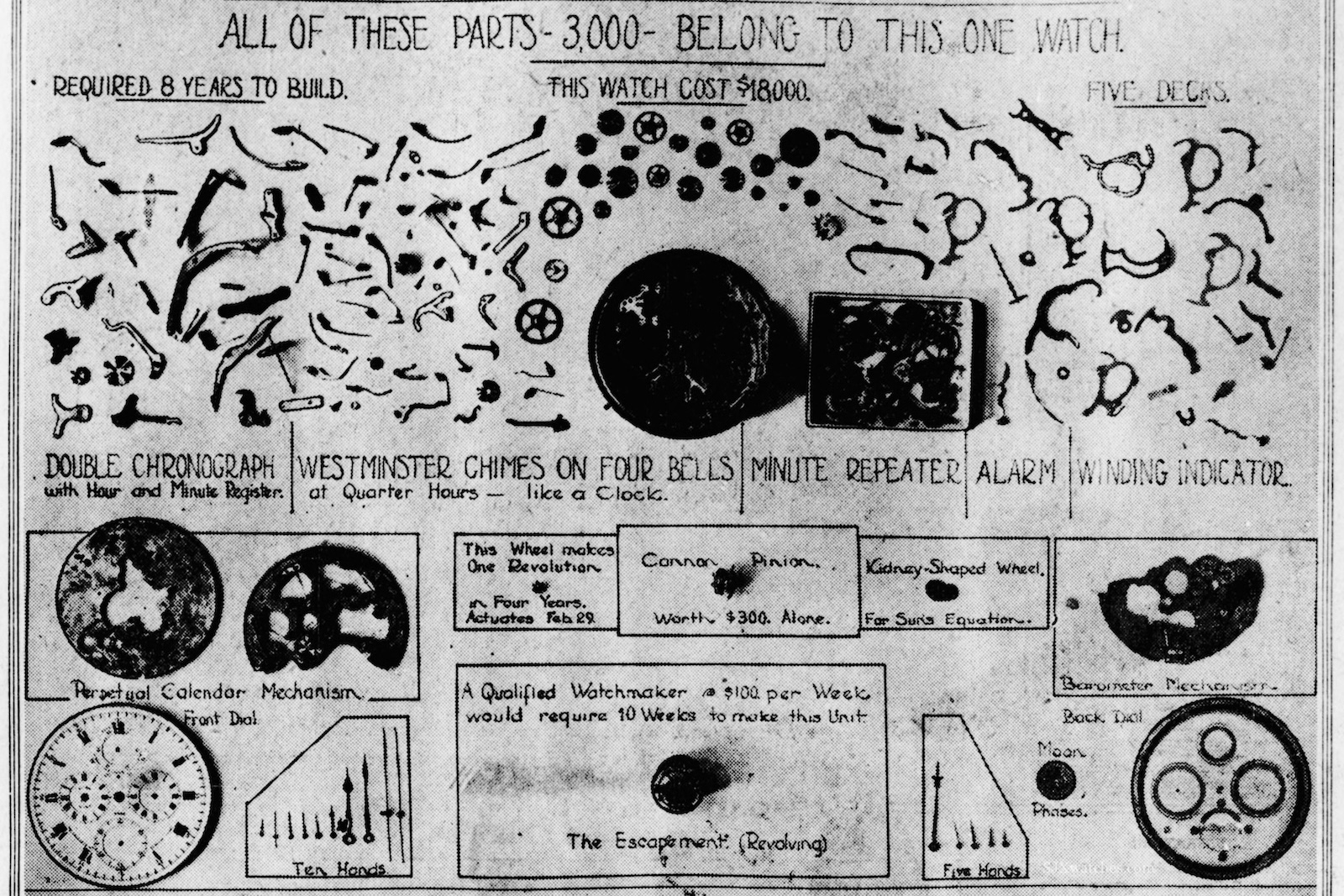

The most elusive of Lee’s known super-complications is the second Dent. The only pictures I can provide are from articles in The National Jeweler and The Jeweler’s Circular.

According to Louis Elisée Piguet: Six Générations d’Horlogers de La Vallée de Joux by Fritz Osterhausen, Louis Elisée Piguet’s archives list a pair of matching duo-face English-style ebauches (8’400 and 8’401). Piguet sold both movements to Capt & Cie. in 1904 for the princely sum of 3500 francs each, so there are likely two of these watches. David Penny’s reprint of the 1910 Nicole, Nielsen & Co. catalog lists these movements as the Type 50, the most complicated watch offered, with pricing on request.

Signed Dent, not shown in the collection spread. The pins on either side of the crown set the time and alarm, while the buttons likely actuate the rattrapante and winding rocker. Image – The Jewelers Circular and Homological Review 1924

Three barrels power the movement and striking mechanism, all wound from the crown with the aid of a rocker mechanism also seen on other three-train movements by Louis Elisée Piguet. On the front is a split-second chronograph with stacked minutes and hours registers at three o’clock, while this may not seem significant now, chronographs with hours totalisers were extremely rare at the time.

The alarm, which is wound externally, can set the alarm to the exact minute from the dial at nine o’clock. There is a power reserve and barometer at 12 o’clock. On the back is another perpetual calendar with date from the centre, along with day, month, leap year cycle, moon phase and discrete moon age by hand. The watch covertly has the equation of time, possibly hidden under the rear bezel, like the J.W. Benson’s concealed date, and a one-minute tourbillon hiding between the dials.

An example of a watch with seven gongs and two discrete striking systems, one of which uses a pinned cylinder in place of racks to play a melody on the new hour. Such watches were usually made for the English market. Image – Antiquorum

In a typical repeater or clock watch with a single quarters rack, the first quarter is indicated by a pair of high and low notes, the second by two pairs of the same notes, the third by three and the fourth by none. A quarters rack typically chimes notes 1, 2, 3 then the first, second, and third quarters will always follow the same pattern of notes 1, 2-1, and 3-2-1. Since the melody of Westminster chimes would be 1-2, 3-4, 5, 1-2, 3, 4 ,5, four different racks are needed to reproduce the quarters accurately.

Patek Philippe’s “Duc de Regla” of 1910 and Star Calibre 2000 also have four-rack Westminster systems, while the Graves Supercomplication (and most other watches claiming Westminster chimes) are imitations using a single quarters-rack. Lee’s watch cost around US$18,000 according to Kingsley. For reference, the Graves Supercomplication that was ordered decades later was only around US$15,000, reflecting the relative cost disparity between English and Swiss watchmaking at the time.

In addition to the Westminster chimes, Lee’s super-complication also has an independent minute repeater, or even a minute repeating grade et petite sonnerie on two gongs, which is why you can see a total of five quarters racks, two hours racks, and one minutes rack in the picture. Assuming five gongs in the Westminster (four for quarters and one for hours), two for the normal strikes and one for the alarm, the watch has eight gongs. Kingsley said the watch comprised 3,000 parts, which I suspect was an exaggeration, but not by much.

Dent super-complication parts spread. Note the movement has a kidney shaped cam yet no apparent means to display the equation of time. Image – Boston Evening Transcript. March 15, 1924

Mystery S. Smith & Son

Also described by Kingsley, but not pictured, is a 75 mm diameter, 38 mm-thick tourbillon by S. Smith & Son, with chimes on four gongs, a “double chronograph” with hours and minutes totalisers, perpetual calendar, signs of the zodiac, equation of time, moon phase, and power reserve indicator. Kingsley didn’t mention if the watch was double-dialled, but noted a silver dial with a gold inlay.

Founded by Samual Smith, S. Smith & Son was a retailer similar to J.W. Benson in Lee’s day, but leaned into manufacturing after the war. Smiths became a major manufacturer of instrumentation, clocks, and wristwatches. Later known as Smiths, the firm wound down its watchmaking division by the 1980s, but the conglomerate is still active in a range of industrial engineering sectors, including gaskets, tubing, security products, and electronics.

S. Smith & Son “Astronomical Watch”. Image – The Graphic November 19, 1921, page 598

S. Smith & Son’s “Astronomical Watch”, commissioned by an unknown American client before the First World War according to The Graphic, is approximately the same diameter and thickness. The watch has a perpetual calender, equation of time, up/down, chronograph with hours and minutes totalisers, tourbillon regulator, and grande et petite sonnerie with trip minute repeating.

The gold inlaid silver dial on the back has hours and minutes of sidereal time, geared to a planisphere which displays the sky above London – 315 hand-painted stars include all constellations of the zodiac. The “Astronomical Watch”, is not a perfect fit, as it lacks split-seconds and Westminster chimes, however it would be an extraordinary coincidence if the two were unrelated.

S. Smith & Son “Astronomical Watch”. Image – The Graphic November 19, 1921, Page 598

Interestingly, this watch passed through the hands of Audemars Piguet, where it was nicknamed “Grosse Piece”, reflecting both its size and complication. Today it remains the most complicated movement Audemars Piguet has been involved in producing. The war delayed completion of the watch until 1921, after Lee’s death. If these two watches are the same, it would explain why it’s estranged from the rest of Lee’s collection.

Lee’s Legacy

Why do we remember Graves and Packard but not Lee? Probably because Lee almost exclusively patronised long-gone English watchmakers. Without Patek Philippe fanning the flames of dubious Graves-Packard rivalry, would we remember the pair today?

Elliot C. Lee isn’t forgotten though, he’s best known today as president of the AAA and an, albeit unsuccessful, automotive entrepreneur – remembered for what he did, not what he bought.

Back to top.