In-Depth: Girard-Perregaux’s True Constant-Force Escapement

From Breguet to the Neo Constant Escapement.

Ten years after it arrived on market, Girard-Perregaux revived its most notable modern-day invention with the Neo Constant Escapement. Operating on the same principles as the original, the Neo Constant Escapement (NCE) features an upgraded movement inside a more compact case.

A combination of a historical concept originating with Abraham-Louis Breguet and cutting edge horology, the NCE retains the defining invention of the original – a true constant-force escapement. “True” because the constant-force mechanism, comprising a lozenge-shaped silicon spring, is integrated with the pallet lever, which in turn interacts with a “natural” escapement of twin escape wheels.

While the key concept has been retained, the rest of the NCE, however, has been improved over the original, with wearability in particular having been enhanced.

Initial thoughts

The fundamental concept of the NCE is appealing because it successfully combines a significant historical invention, Breguet’s double-wheel escapement, with an innovation that is entirely 21st century, a compliant mechanism in silicon. Both are brought together in an elegant yet ingenious manner.

The basis of the movement is Breguet’s échappement naturel, the “natural” escapement with two wheels that has been adopted in the modern day, in a variety of modified forms, by Voutilainen, F.P. Journe, and Charles Frodsham. But the natural escapement here has been enhanced with a constant force mechanism made up of a single piece of flexible silicon that ensures the pallet lever pivots back and forth with the same degree of energy on each motion.

It’s a simple idea yet one that was complex to execute – requiring the invention of silicon in watchmaking to be realised – and is arguably one of the few contemporary inventions that seamlessly marries a historical innovation with something completely new.

Geeks will realise that the movement is not only about the escapement, but also about the power supply. The calibre relies on two large barrels, both visible on the dial, that give it a seven-day power reserve. Twin barrels and a lengthy power reserve ensure torque that is as constant as possible, further improving chronometry.

Given its technical merits, I was impressed by the original Constant Escapement L.M. at its launch in 2013, but that was hindered by its 48 mm case and high price tag. The original was 48 mm in diameter, huge even by the standards of that period, and retailed for about US$100,000, pricey compared to much else then (for comparison, the Lange Datograph Up/Down was about 10% less expensive then).

The NCE resolves all of that with a more compact case and a relatively more affordable price tag. At 45 mm, the NCE is not a small watch, but wearable enough considering the large diameter of the movement. The titanium case plays a key role in wearability; the watch is surprisingly lightweight given the diameter (and substantially lighter than the original that was white gold).

Interestingly, the NCE retails for just under US$100,000, which is almost exactly the same as it was a decade ago. In the intervening years everything else has gotten more expensive – but not necessarily more innovative or interesting. The Constant Escapement, on the other hand, remains an impressive invention, and significantly more affordable compared to the original.

In terms of design, the NCE maintains the modern aesthetic of the original. While I understand the stylistic continuity for the sake of brand identity, I hope GP offers an alternative presentation for the Constant Escapement. With its origins in a 19th century escapement, it would be fitting to install the invention in something that is clearly modern, but with obvious classical elements, much like the invention itself.

A three-decade odyssey

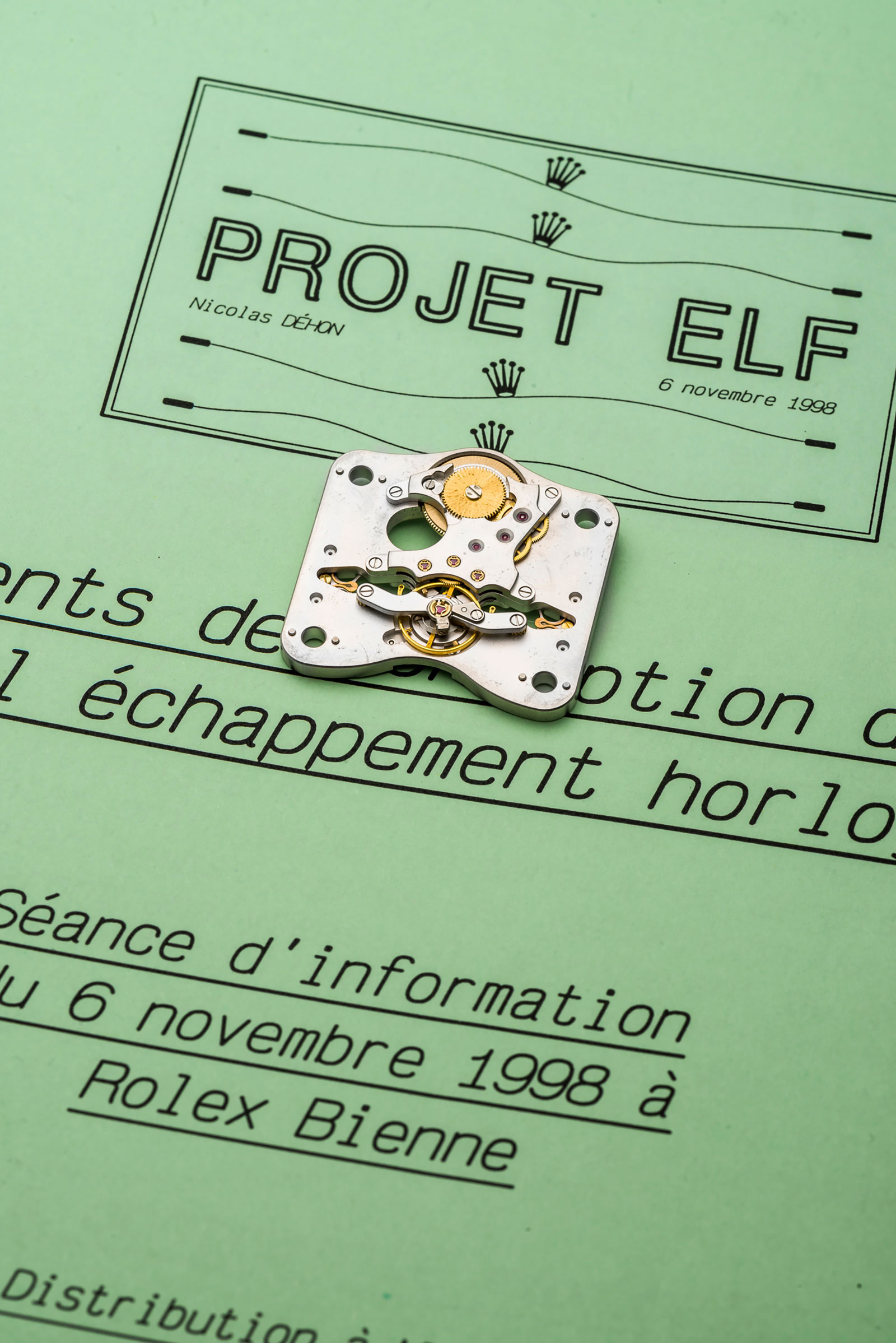

The origins of the Constant Escapement lie with constructor Nicolas Dehon, who hit upon the idea in 1997 while he was working at Rolex. His inspiration is now well known, having been recounted over various interviews over the years: Mr Dehon was absentmindedly bending his ticket while on a train and realised the same principles of a flexible, buckling part could be applied to an escapement.

Rolex attempted to develop the concept, which was codenamed Project ELF, short for echappement, lame, flambage (which translates as “escapement, blade, buckling”). Several prototypes were made, including one that sold at Antiquorum in 2018, but eventually abandoned it as metal alloys were not up to the task. It would take the arrival of silicon in watchmaking to transform Mr Dehon’s idea into reality.

A Project ELF prototypes that sold at Antiquorum in 2018. Image – Antiquorum

After leaving Rolex in 2002, Mr Dehon spent the next six years at GP working on the Constant Escapement, bringing it closer to completion. Several more years passed after he left GP for Patek Philippe, during which the movement was further refined, including by lowering the frequency and lengthening the power reserve, to ensure reliable and consistent operation.

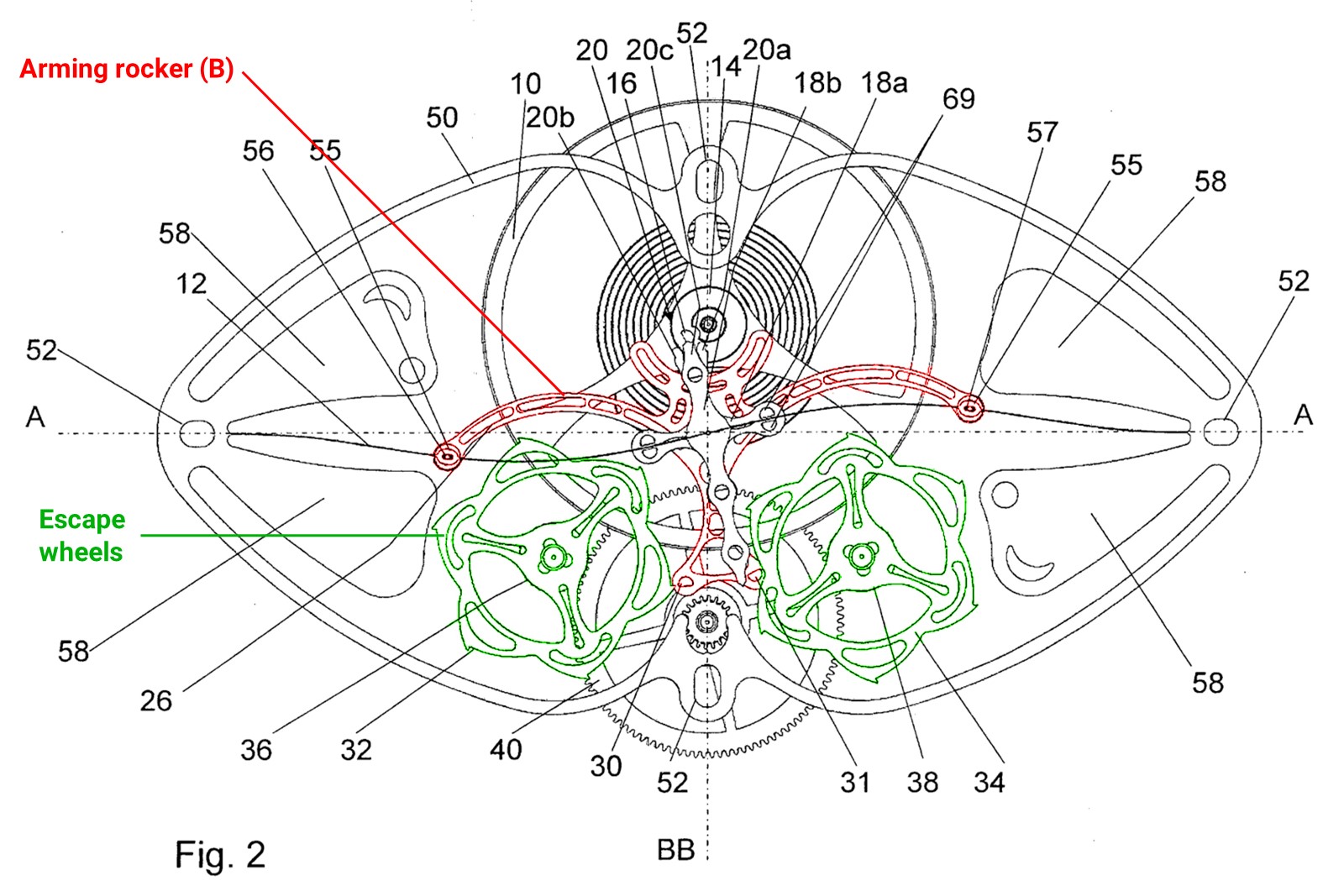

The diagram of the entire escapement from the 2008 patent

The Constant Escapement L.M. finally made its debut as a commercially-available watch in 2013. “L.M.” was a tribute to Luigi “Gino” Macaluso, the then-owner of GP who passed away three years prior, but had originally given the green light for the project in 2002. Unsurprisingly, its technical merits allowed the Constant Escapement L.M. to clinch the “Aiguille d’Or”, the top prize at the Grand Prix d’ Horlogerie de Genève 2013.

The story of the Constant Escapement came full circle when Mr Dehon returned to GP in 2018. He spent most of the next two years working on the second-generation Constant Escapement, which would eventually become today’s NCE.

How it works

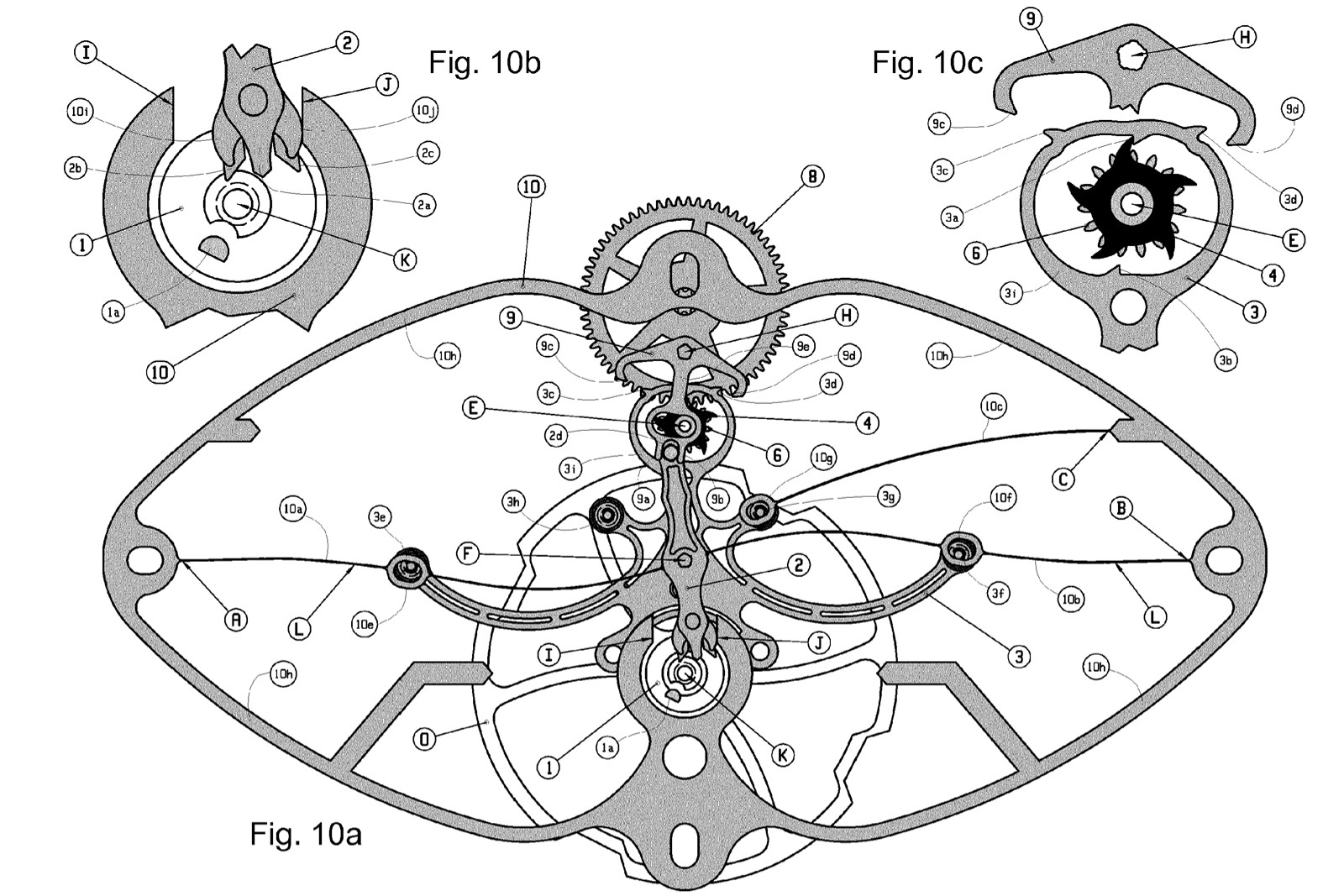

The fundamental idea behind the NCE remains the same as it was when the first prototype was completed in 2008. The escapement has twin escape wheels and a bow-shaped pallet fork that locks and unlocks the escape wheels; this locking and unlocking regulates the power discharged by the mainsprings, and gives the watch its beat. In short, its basic operation is similar to that of the traditional Swiss lever escapement with a single escape wheel.

But attached to the pallet fork is a thin silicon blade that horizontally across the dial; this blade is part of a lozenge-shaped silicon frame. The blade ensures constant force in the escapement, or more specifically, a constant impulse on every tick and tock as the pallet lever swings back and forth.

Because the blade is attached to the pallet fork in three points along its length, the blade buckles in one direction, and then the other, as the pallet fork moves back and forth.

The stiff nature of silicon means the blade shadows the motion of the pallet fork: when the blade is flexed to the maximum in one direction, as the pallet fork goes one way, the blade will naturally tend to flex in the opposite direction, just as the pallet fork oscillates in the other direction. This encapsulates Mr Dehon’s original concept behind the Constant Escapement: a train ticket made of stiff card flexed between two fingers tends to pop out in the opposite direction when given a small push.

The constant-force element of the invention lies in the phyiscal properties of silicon. In an ordinary movement, the amplitude of the balance wheel drops as the power reserve runs down. But the silicon blade gives the pallet fork a constant impulse with every oscillation as the blade flexes and pops back out with exactly the same energy each time. As a result, the escapement always operates with a constant impulse regardless of the mainsprings’ state of wind.

But the silicon blade itself requires energy as it needs to be recharged on each oscillation, requiring an impulse to flex it in each direction. This explains in part the double escape wheels. The symmetrical arrangement of twin wheels is a convenient means to recharge the blade in both directions. As the pallet fork oscillates, it unlocks the escape wheels, which in turn impulse an intermediate lever that flexes the silicon blade, storing energy for the next oscillation of the escapement.

A diagram from the original Constant Escapement patent showing the silicon frame with its blade spring as well as the bow-shaped pallet fork

Even though the escapement is constant force, eliminating the need for constant torque from the mainspring, the movement has been constructed to optimise mainspring torque in order to maximise its chronometric performance. Visible on the dial are twin barrels that unwind in parallel and provide an impressive seven days of power reserve.

As is the case with most long-power reserve movements, the two mainsprings actually store a bit more energy than seven days, but the movement incorporates a stopwork that halts the barrels at the seven-day mark. This ensures that the torque is linear throughout the weeklong running time, since a mainspring produces progressively diminishing torque in its final lap.

Updating the design

The styling of the NCE is descended from the original, but even more modern. It’s the most logical visual style for such a cutting edge escapement, but the opposite might work as well.

Given the historical basis of the Constant Escapement, a classical version of the watch would make sense. It would be a contrast – the silicon escapement against a guilloche dial for instance – but it would be coherent and appealing if designed correctly. I for one would like to see another version of the Constant Escapement, particularly because high-tech mechanical horology is so rarely done in a classical manner.

The NCE of 2023

Most importantly, the NCE is a mechanical evolution of the original CE, with numerous patents and refinements to the design for better reliability. The major addition is a new latching mechanism for the pallet fork assembly, preventing the blade spring accidentally unbuckling in the event of shocks to the watch.

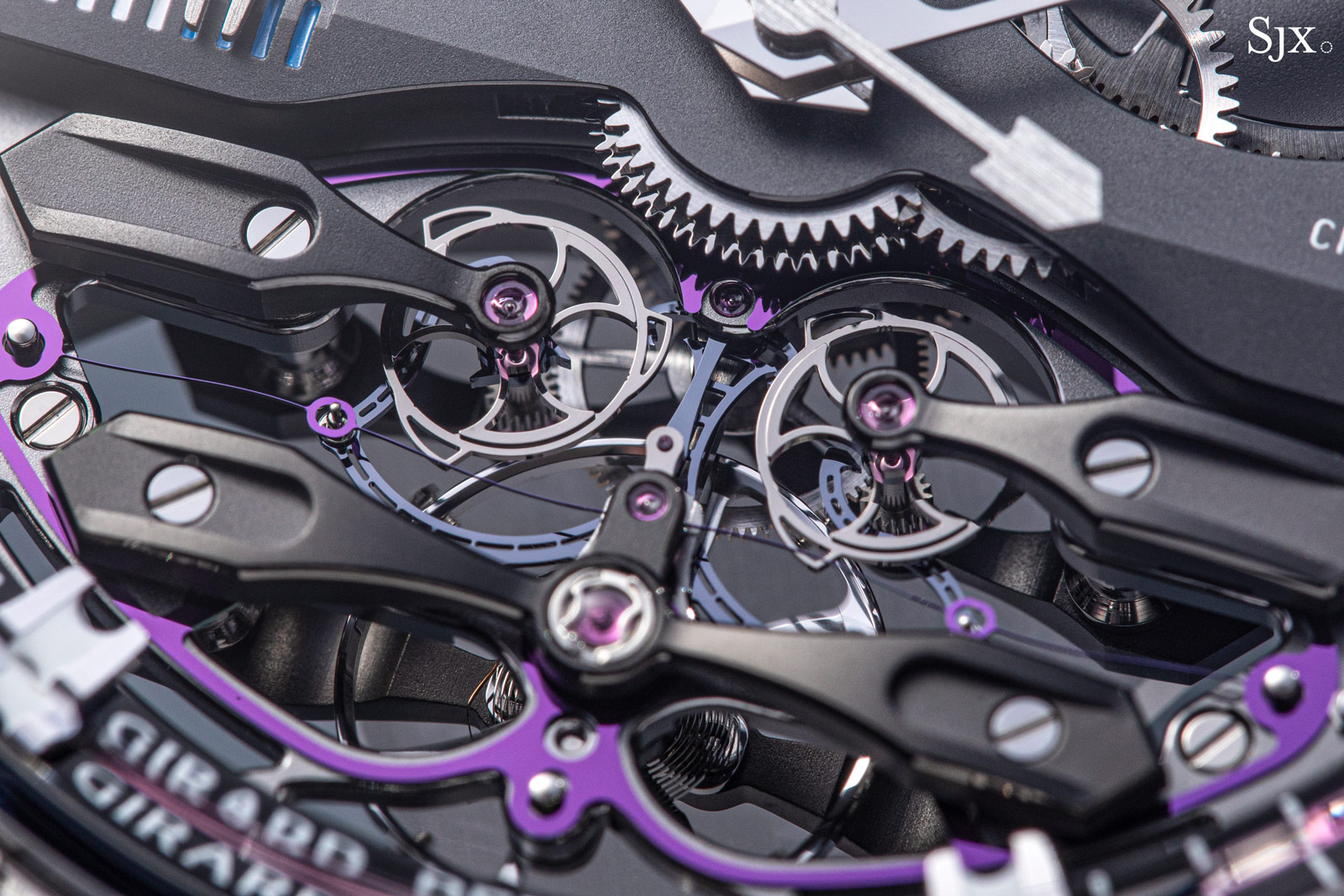

Additionally, the design of the intermediate lever that recharges the silicon blade has been overhauled. It now has two distinct asymmetrical “arms” on both ends that protrude inwards to engage escape wheels. The asymmetrical design is simply a result of the escape wheels configuration – while both are symmetrically arranged, they rotate in the same direction rather than mirroring each other.

This updated mechanism also shrinks the size of the escape wheels. The two visible grey tri-lobed wheels are now aesthetical, with the actual escape wheels now hidden underneath as tiny three-pointed star wheels. These star wheels are visible when the movement is viewed from the back of the watch.

The three-pointed star wheels just barely visible under the tri-lobed wheels

Wearability-wise, the original CE from 2013 was a large, heavy watch with a generously arranged dial; the size meant the elements could be spaced out. In hindsight, the dial felt a bit empty.

In contrast, the NCE improves the design by leaving practically no empty space on the dial. The 3 mm reduction in diameter makes a substantial difference in the density of the dial, giving it an intricate, mechanical look. Even though the Constant Escapement remains the same size, it is now more prominent and visible.

The 2013 original

One of the most notable improvements is the relocation of the hour and minute hands to the centre. In the original, the two hands were in a sub-dial at 12 o’clock, while the seconds was central – a peculiar separation of indications that didn’t really make sense. The NCE has all three hands in the centre, which is both logical and legible.

The complex mechanics presented on the front make it ideal for the “Neo” case that GP has applied to most of its watches with open dials.

Made up of a case without a bezel and a highly domed crystal, the Neo case maximises visibility of the dial elements. By doing away with the bezel, the face feels more airy despite being packed with detail.

The case is 45 mm in diameter, which limits its wearability to those with medium or large wrists. But it is titanium, and with relatively thin walls, so the NCE is pleasantly lightweight, particularly when compared against the white gold original.

Though the size is large, the case is as compact as it can be given the movement size. The movement essentially maxes out the available space inside the case, so much so that the back is screwed to the lugs, which are wider than the case walls.

Details

The movement inside the NCE is finished appropriately for watch of this price, though many of its finer points are not easily observed due to the dark finish on majority of the components. This is true on both the front and back.

On the front, the most prominent example of decoration are the twin barrels. Both are seated under an open-worked barrel bridge that’s frosted on top and bevelled along its edges. The bevels are wide and rounded, while the countersinks are bowl-shaped, indicating the finishing touch was done by hand.

The bevelling on the bridge doesn’t have the inward angles associated with the highest level of artisanal finishing, but that perhaps can be something for a classical version of the watch.

Below the barrel bridge, the lower face of both barrels sport a notably fancy finish. They have recessed frosted areas with raised borders finished with radial graining, while the inner edges of the borders feature anglage. The complexity of this finishing on these two wheels imply it was done with the help of machines, but the result is attractive, albeit not apparent at a distance due to the dark grey finish and lack of contrast.

Over on the back, the finishing is of equal quality, but there is even less visual contrast than the front. Given the skeletonised bridges and architectural style, the rear of the movement could be easily made more striking with contrast-colour treatment.

A few details on the back are worth paying attention to. One are the twin barrels, both with ratchet wheels featuring an identical finish as the underside visible on the dial.

Another is the linear gear train made up of wheels that have chamfered spokes and inner edges. The wheels start at the barrels and culminate at the Constant Escapement.

But just above the gear train, at the 12 o’clock position, is a grand sonnerie-style winding click, a little bonus that enthusiasts will appreciate. Featuring double click springs and a ratchet wheel, this allows both barrels to be wound simultaneously via the crown, just like in a grand sonnerie.

Concluding thoughts

The original Constant Escapement L.M. was one of the most technically interesting watches of its day, but never gained the traction it should have for reasons including price, size, and broader market sentiment at the time. The NCE arrives a full decade after the original, yet it still manages to be one of the most technically interesting of today, illustrating the impressive degree of innovation contained within the concept.

In every aspect the NCE is an improvement over the original – while being less expensive in real terms – making it a far more compelling proposition. That said, the hyper-modern aesthetic is not for everyone, which is why I hope a classical version is in the pipeline.

Key facts and price

Girard-Perregaux Neo Constant Escapement

Ref. 93510-21-1930-5CX

Diameter: 45 mm

Height: 14.8 mm

Material: Titanium

Crystal: Sapphire

Water resistance: 30 m

Movement: GP09200-1153

Functions: Hours, minutes, seconds, and power reserve display

Winding: Manual

Frequency: 21,600 beats per hour (3 Hz)

Power reserve: Seven days

Strap: Rubber strap with folding clasp

Limited edition: No

Availability: At GP retailers and boutiques

Price: US$99,600

For more information, visit Girard-perregaux.com.

Back to top.