Book Review: Konstantin Chaykin: Haute Horlogerie, With Russian Soul

The Russian master watchmaker's story.

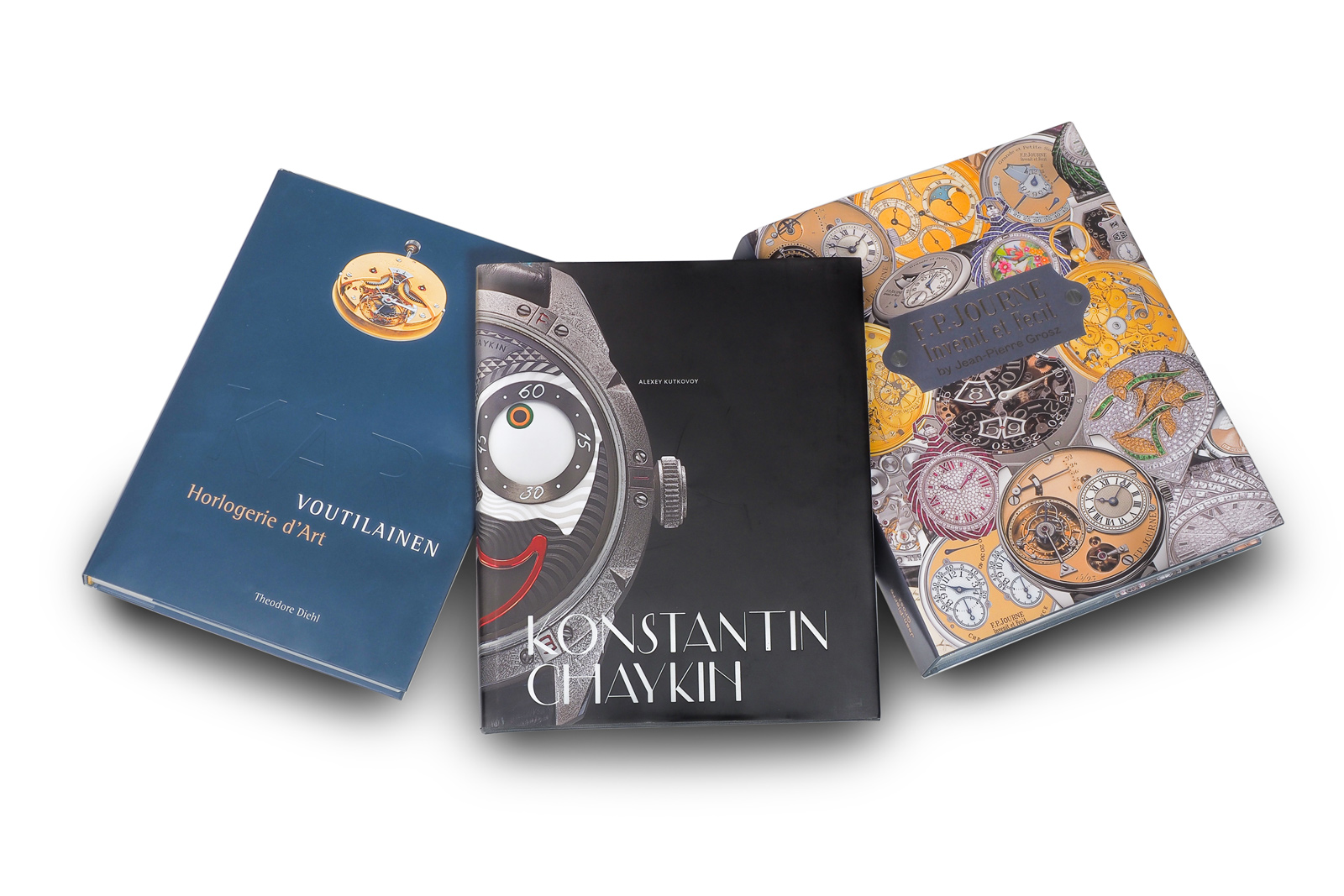

Konstantin Chaykin: Haute Horlogerie, With Russian Soul. By Alexey Kutkovoy. Chaykin.ru; €230

Just glancing at Konstantin Chaykin’s repertoire tells you that there must be many stories behind his watches and clocks – they are markedly out of the ordinary.

To tell some of those stories behind the timepieces – and his own story – Konstantin recruited renowned Russian watch journalist Alexey Kutkovoy in 2019.

Despite Konstantin being a perfectionist, Mr Kutkovoy had journalistic freedom. “I was not bound by his control, so I had the privilege to compose my own independent vision with some nice subjects discovered, and I’m happy he left that untouched,” mentions Mr Kutkovoy.

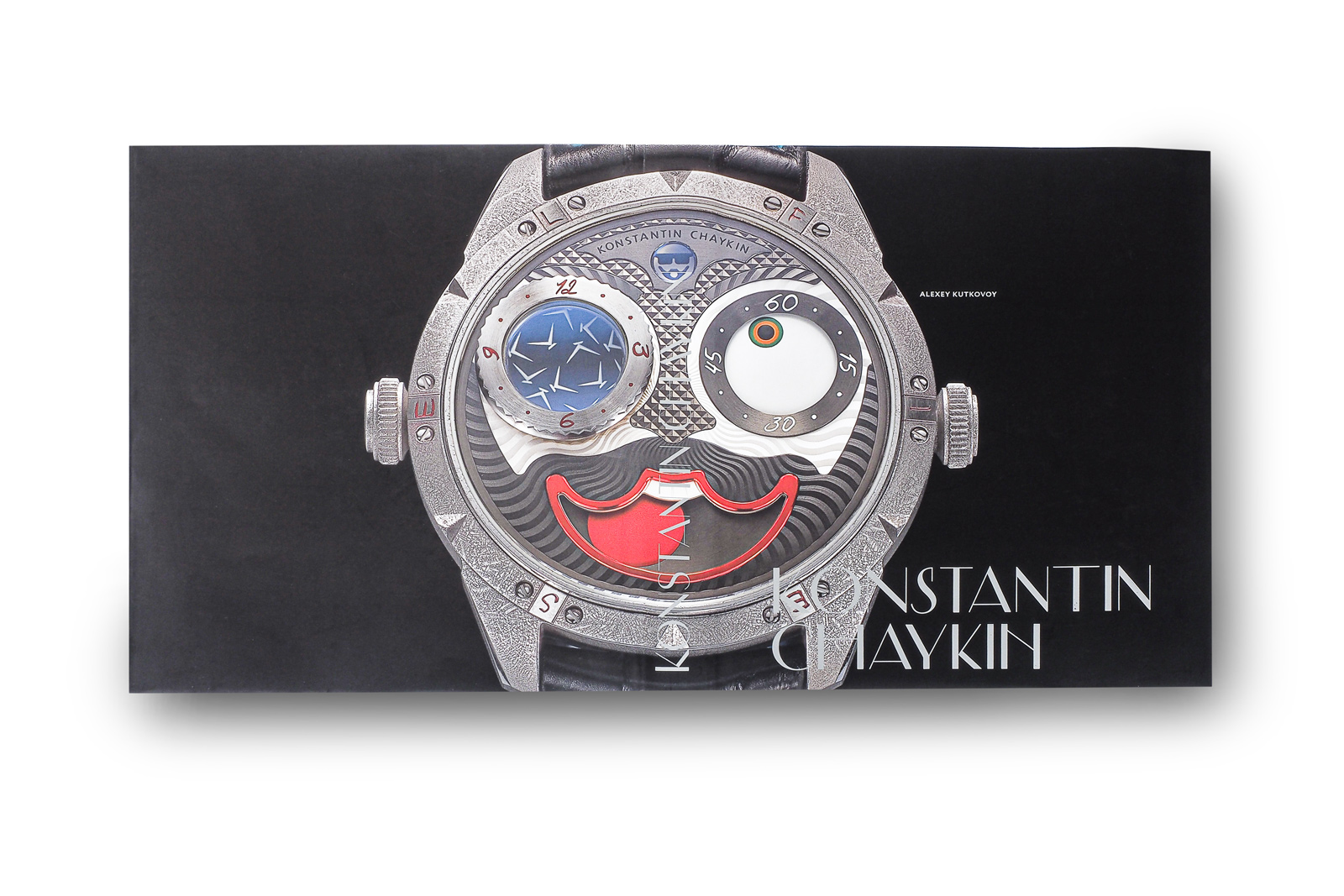

The Joker Selfie made for charity auction Only Watch 2019

His life and work

The result is Konstantin Chaykin, a wide-ranging book that’s both an overview of Konstantin’s first 17 years of watchmaking as well as the myriad tales about his watches and clocks. Konstantin Chaykin is 384 well-filled pages, laid out in an unusual design that befits the individualism found in his watches. Originally published in Russian, the book is now available in English in a limited edition of 1,000 copies.

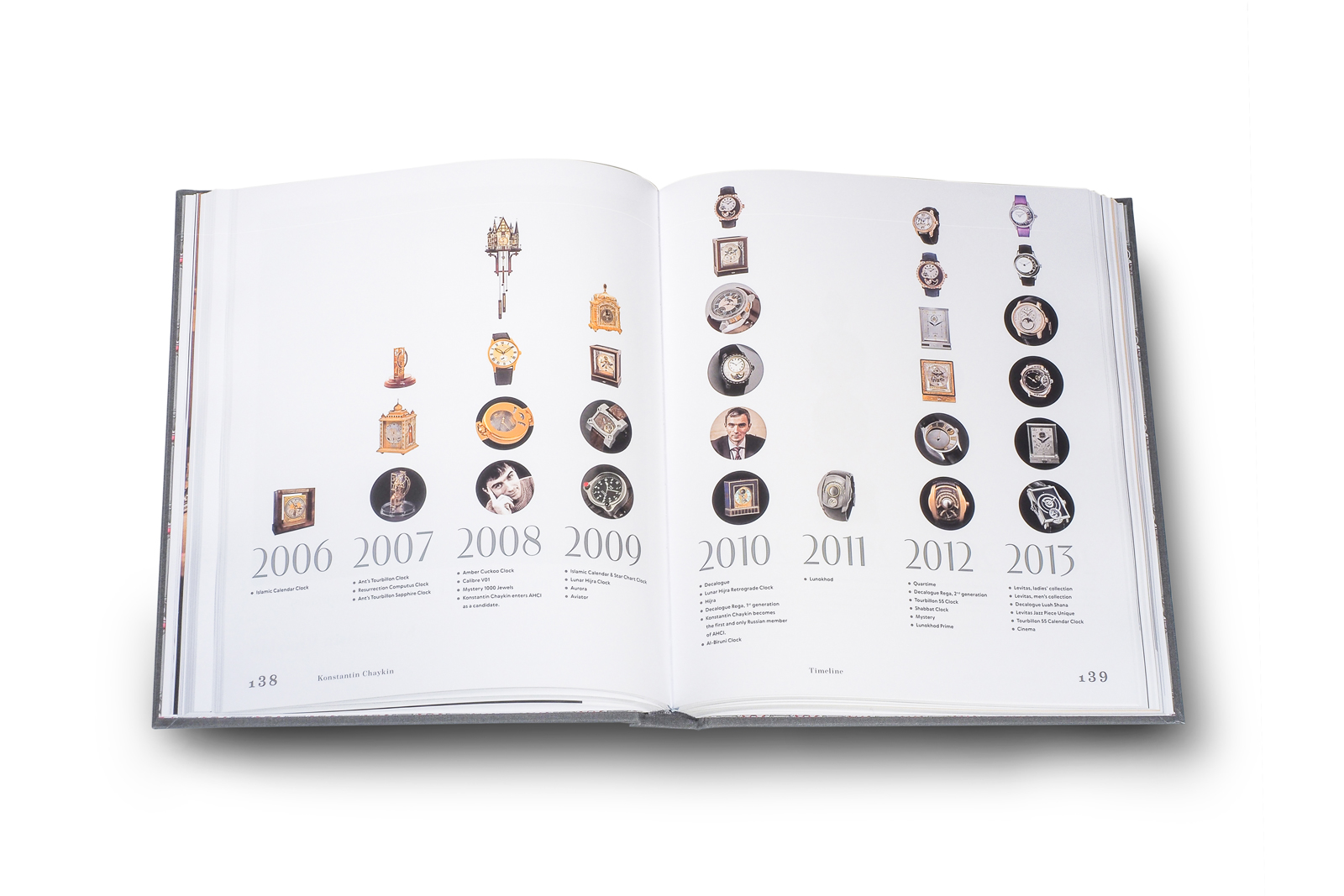

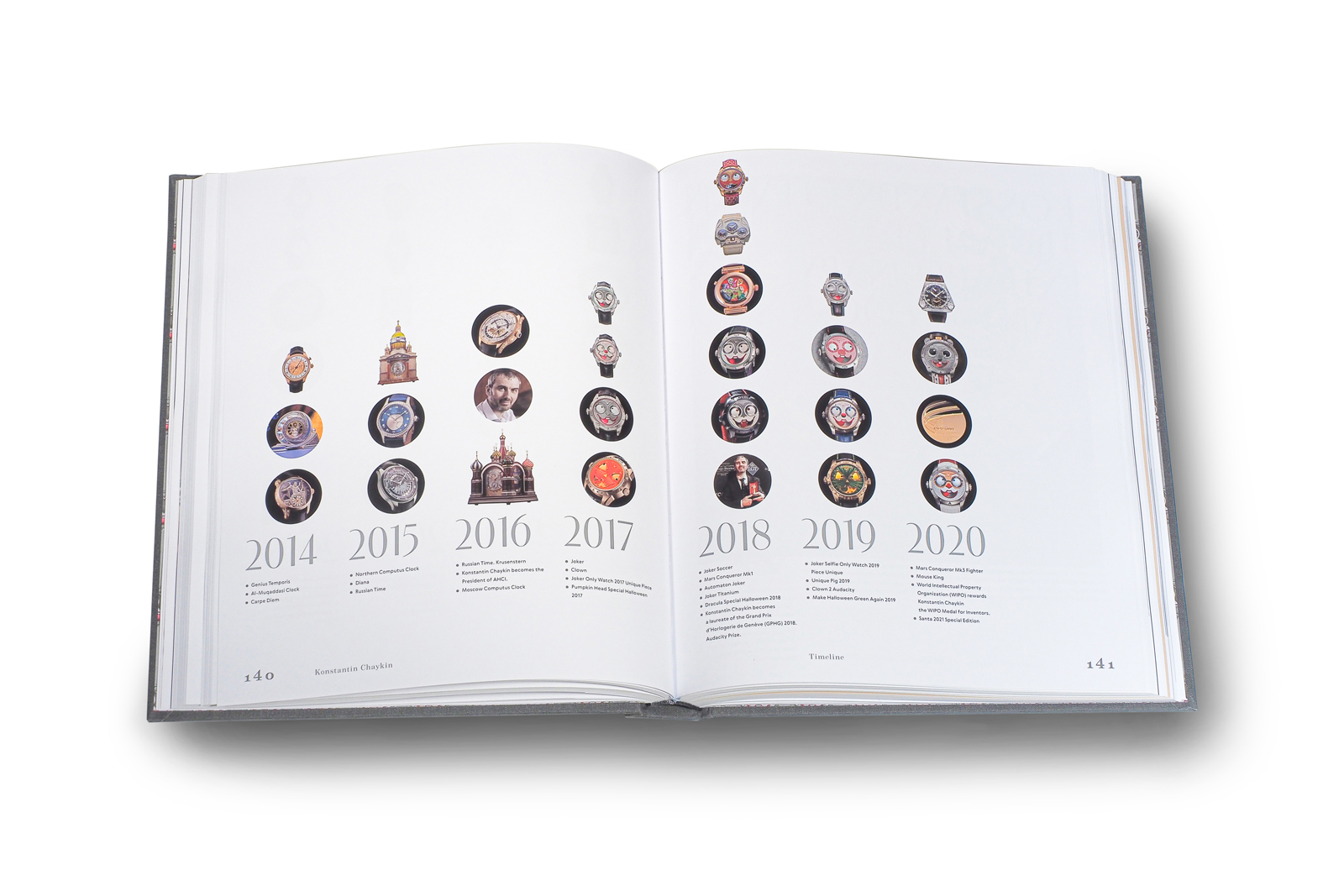

Mr Kutkovoy decided to present Konstantin’s story in two separate threads – a timeline and an evolution of Konstantin’s clock and watch inventions – that presents a detailed history in a most accessible way.

The opened cover of Konstantin Chaykin

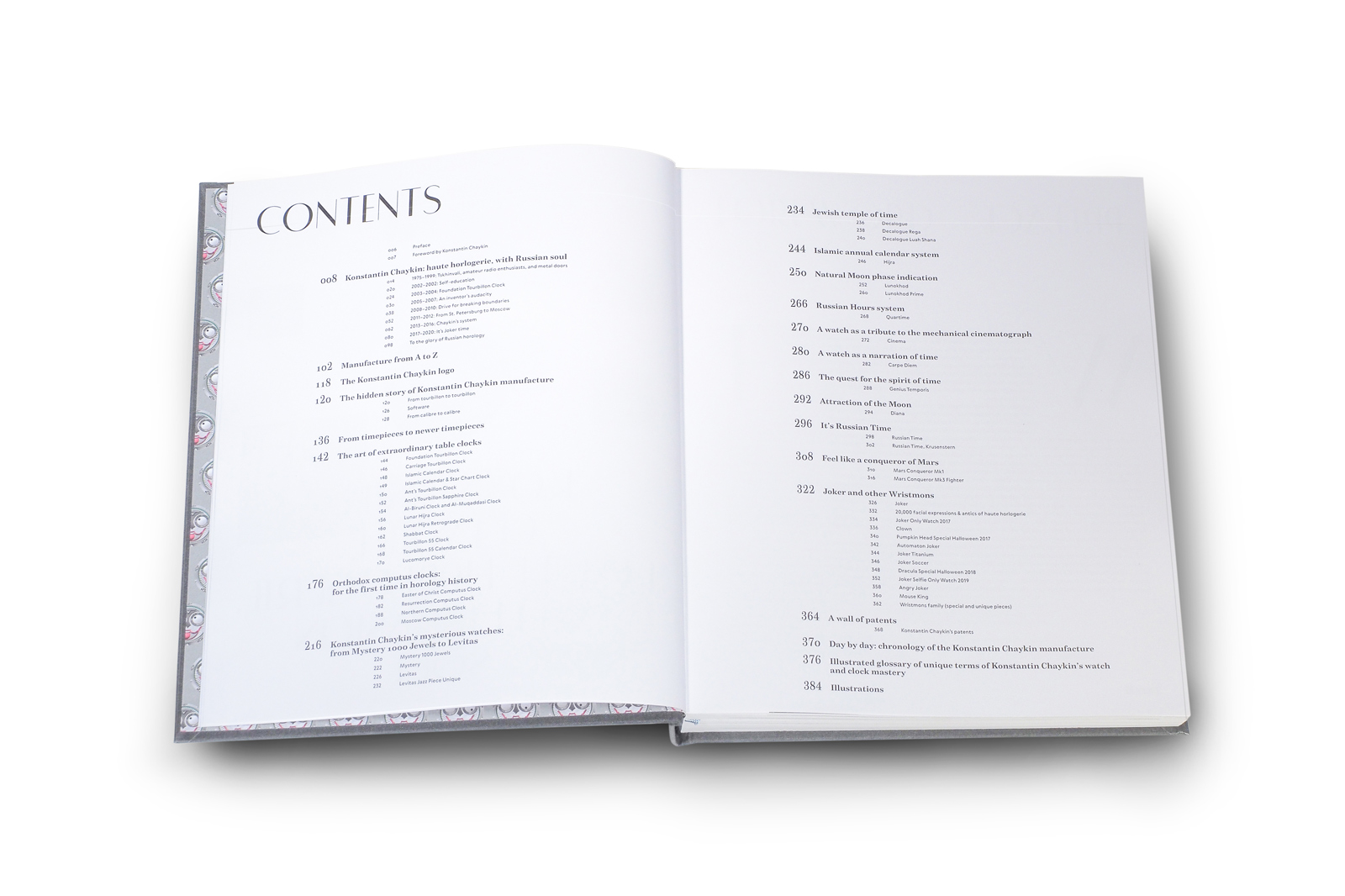

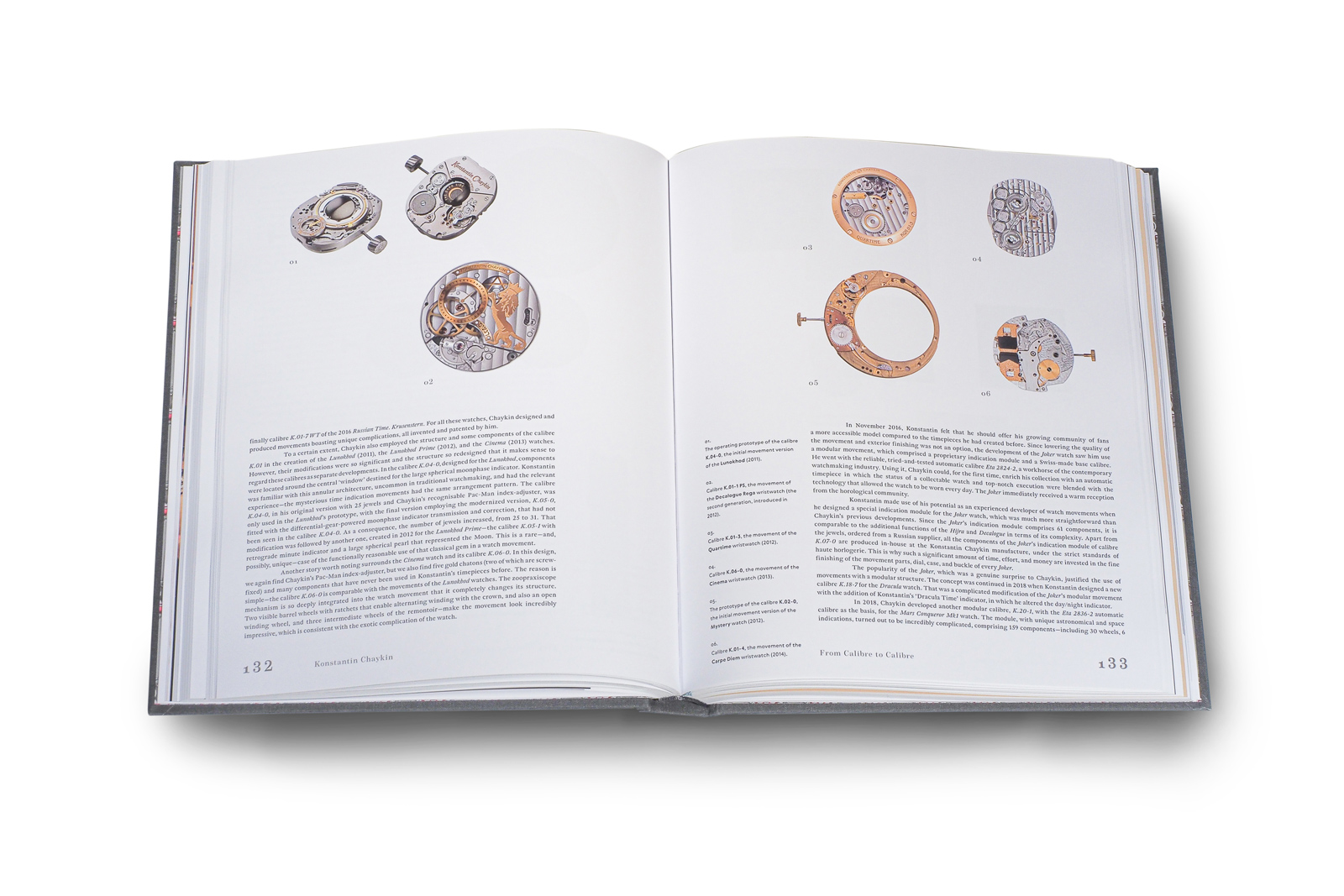

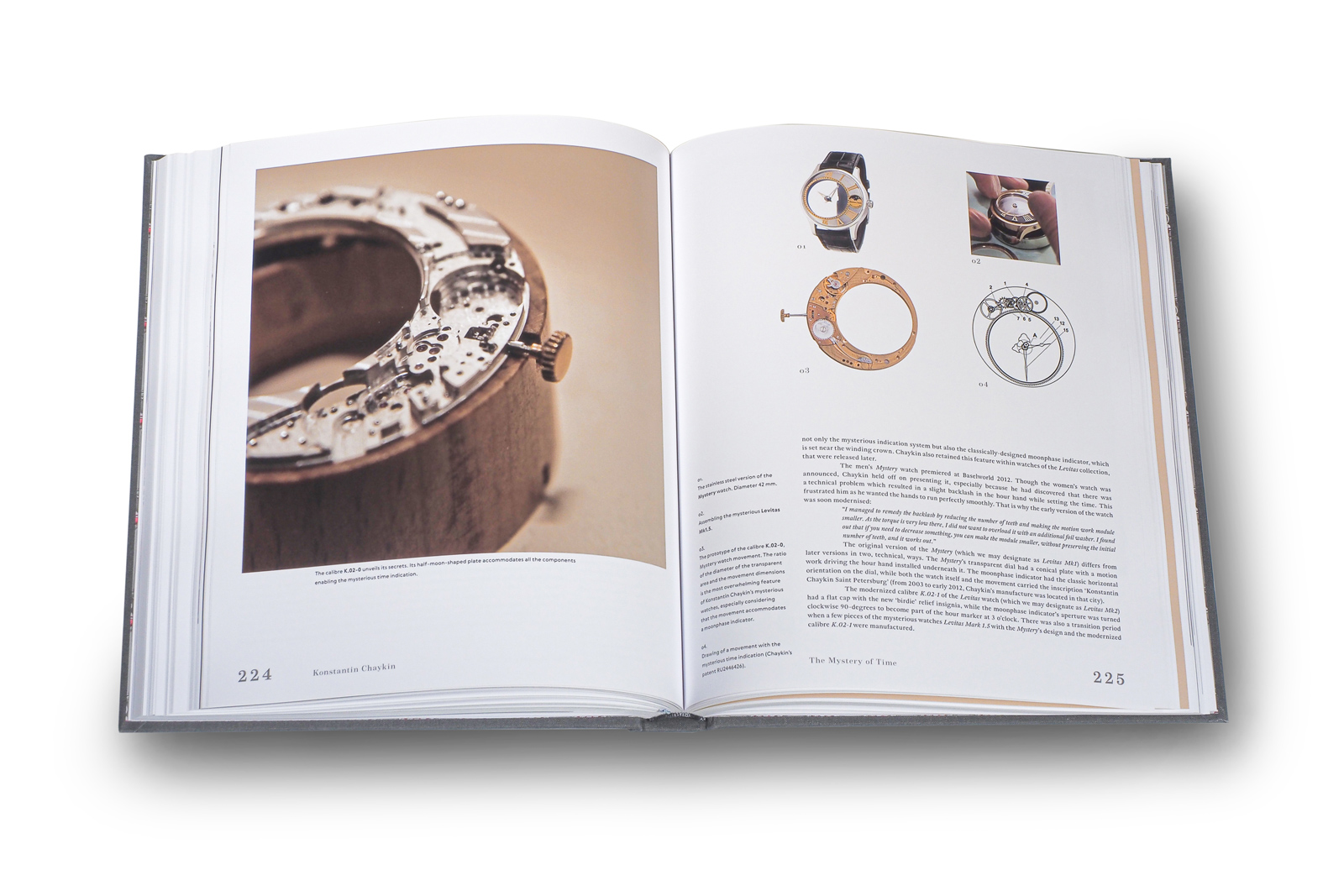

The first section is a chronological narrative, covering Konstantin’s life, interspersed with events in his professional career. The in-house calibres are presented in a separate chapter, followed by a catalogue raisonné featuring all the clocks and watches Konstantin has conceived since the Foundation Tourbillon Clock of 2003, up to the recent variants of the Joker from last year, each explained within a dedicated chapter of two to eight pages.

In between sit the chapters that explain the Konstantin Chaykin logo or cover a visit to his manufacture, all livened up with interesting tidbits of knowledge. The book closes with a timeline of milestones for Konstantin Chaykin and his brand as well as a glossary, incorporating Mr Kutkovoy’s thoughts on the peculiarities of Konstantin’s watches. With the glossary, Mr Kutkovoy says he “tried to add some fun in a horological way… [since] it is like the universe of Konstantin Chaykin and there should be unique language.”

This structure of the book makes it easy to dip into a specific section, while also ensuring that the enthusiast gets a reference on Mr Chaykin’s work despite the surprising lack of an index.

On the other hand, the structure has the inherent risk of annoying repetitions in the content. But Mr Kutkovoy said an effort was made to avoid this pitfall by writing about different details or from another perspective when a subject is repeated in the book.

A glance at the chapter on the Russian Time wristwatch, proves that is mostly fulfilled. In the timeline section, for example, the key facts of Russian Time are summed up, including its principal functions, the clock in the 18th century Peterhof Palace that served as inspiration, and clinching the public’s vote in a Russian watch competition, along with other pertinent information.

Russian Time

A separate chapter that details all of Konstantin’s calibres reveals the base movement within the Russian Time (a Poljot 3105), then explaining the redesign – it was modified beyond recognition – and the in-house module added on top.

Later in the book, the chapter dedicated to this model elaborates on Konstantin’s ideas and goals, while also covering in depth the Krusenstern, a one-off version of the Russian Time. Crucial but esoteric information is not left out: the patent filed for the model takes up one line in the appropriate chapter, and the Russian time system is finally explained in brief in the glossary. This structure applies to all the timepieces covered in the book, which becomes an encyclopaedia of sorts about Konstantin’s clocks and watches.

Serious horology

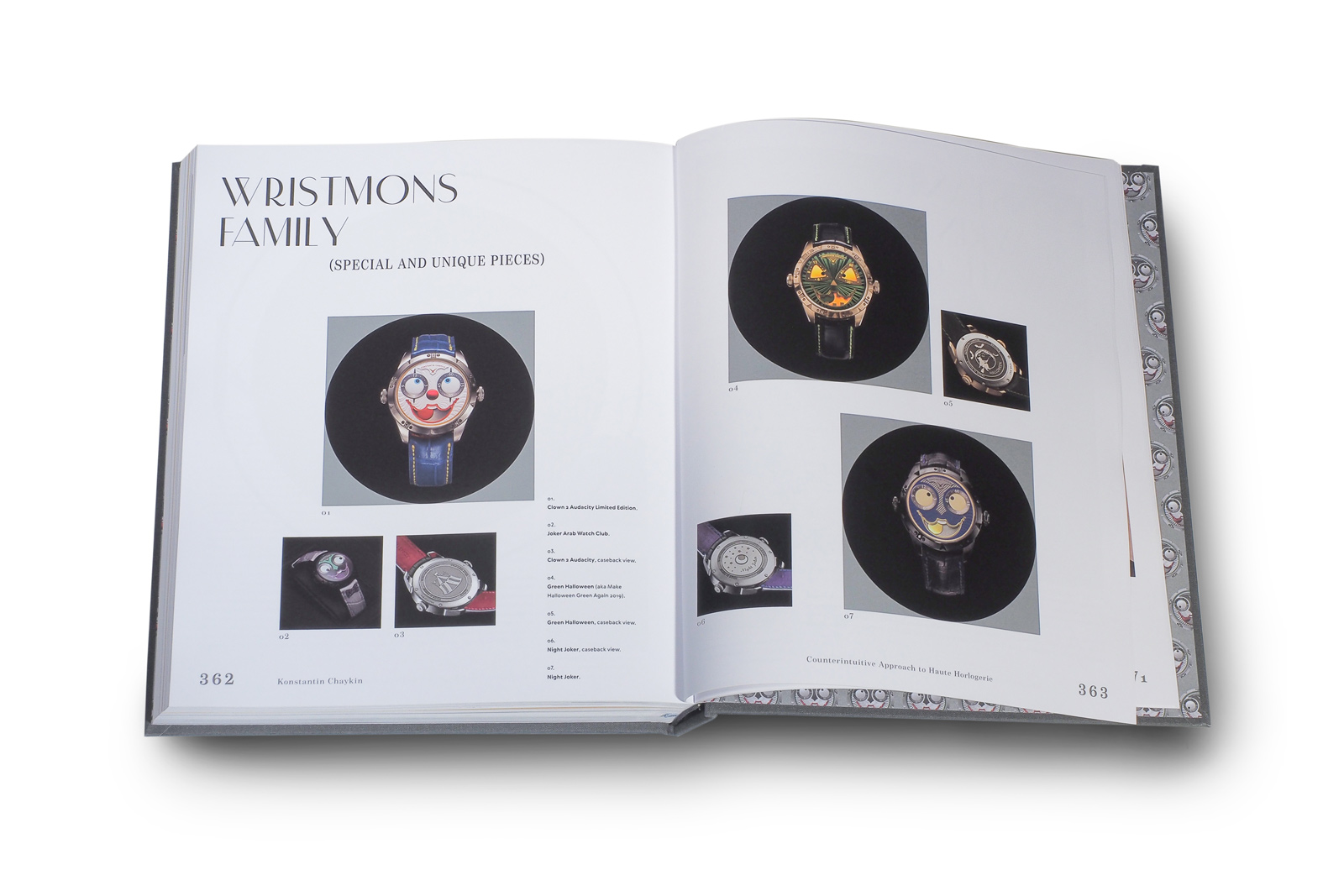

The subject on the cover of Konstantin Chaykin is unsurprising. Together with the other Wristmons watches, the Joker gets quite some acreage within the book. “It was my proposition and he agreed”, said Mr Kutkovoy, “I believe the Joker is one of the most recognisable watches in the world – it’s the real value of the brand”.

As reported in the book, the genesis of the Joker watch is a sample of the honesty found throughout the book. Konstantin’s signature watch only came about because he had to create something quickly for Baselworld 2017 at the last minute, after discovering in November 2016 that the movement of the original watch he wanted to present was not working.

A phenomenal success almost as soon as it was launched, the Joker put Konstantin on the map internationally. The volume of Joker sales provided him with the financial ability to go fully independent by establishing his own manufacturing facilities.

Nevertheless, reading the foreword penned by Konstantin makes it obvious that he wants to be known for more than the Joker, desiring that his complicated clocks and watches become better known to readers outside of Russia.

Konstantin was the author of Horology in Russia – Masters and Protectors, a 2012 book about complicated watchmaking in Russia before him. Now he adds to the body of work with his own biography, which he hopes will “destroy the myth that Russians do not know how to make watches … as it is not only false but also defames the glorious history of our country and sullies the names of great people who have given their lives to creating the most complicated watches and movements.”

After the foreword, though, the book is fortunately devoid of dramatic proclamations. The reader will find an uncommon openness in the content – individuals are named, figures behind business ventures are tallied, third-party movements or parts revealed, and Konstantin’s own failures described.

For the collector thinking about commissioning a watch from Konstantin, it is reassuring to learn about the watchmaker’s easy-going demeanour, never slamming a door even when faced with disappointing partners, but still staying in touch after the partnerships have been dissolved. Through sentences filled with facts the reader can vicariously experience the single mindedness and hard work – consequently neglecting his family as Konstantin notes – needed to make a career as a master independent watchmaker.

There is one omission, likely a consequence of Konstantin wanting international recognition for his highly complicated clocks and watches. Putnik, a brand of low-cost watches Konstantin established a couple of years ago is not discussed.

Mr Kutkovoy managed to squeeze in just one sentence mentioning this entry-level brand. Putnik is significant, in Mr Kutkovoy’s opinion, because the watch offers superb quality – it’s powered by a Swiss-made Ronda quartz movement – that’s far above what one would expect at its US$300 price point.

The hidden Putnik

The life of a master

As recounted in the book, Konstantin considered a second education in art after leaving college with a formal education as radio engineer. Feeling obligated to earn a living, he instead took a job as a locksmith for a steel-door manufacturer, before becoming a dealer in low-end Chinese watches. With a lack of money to hire a watchmaker, Konstantin taught himself to repair the watches he was selling.

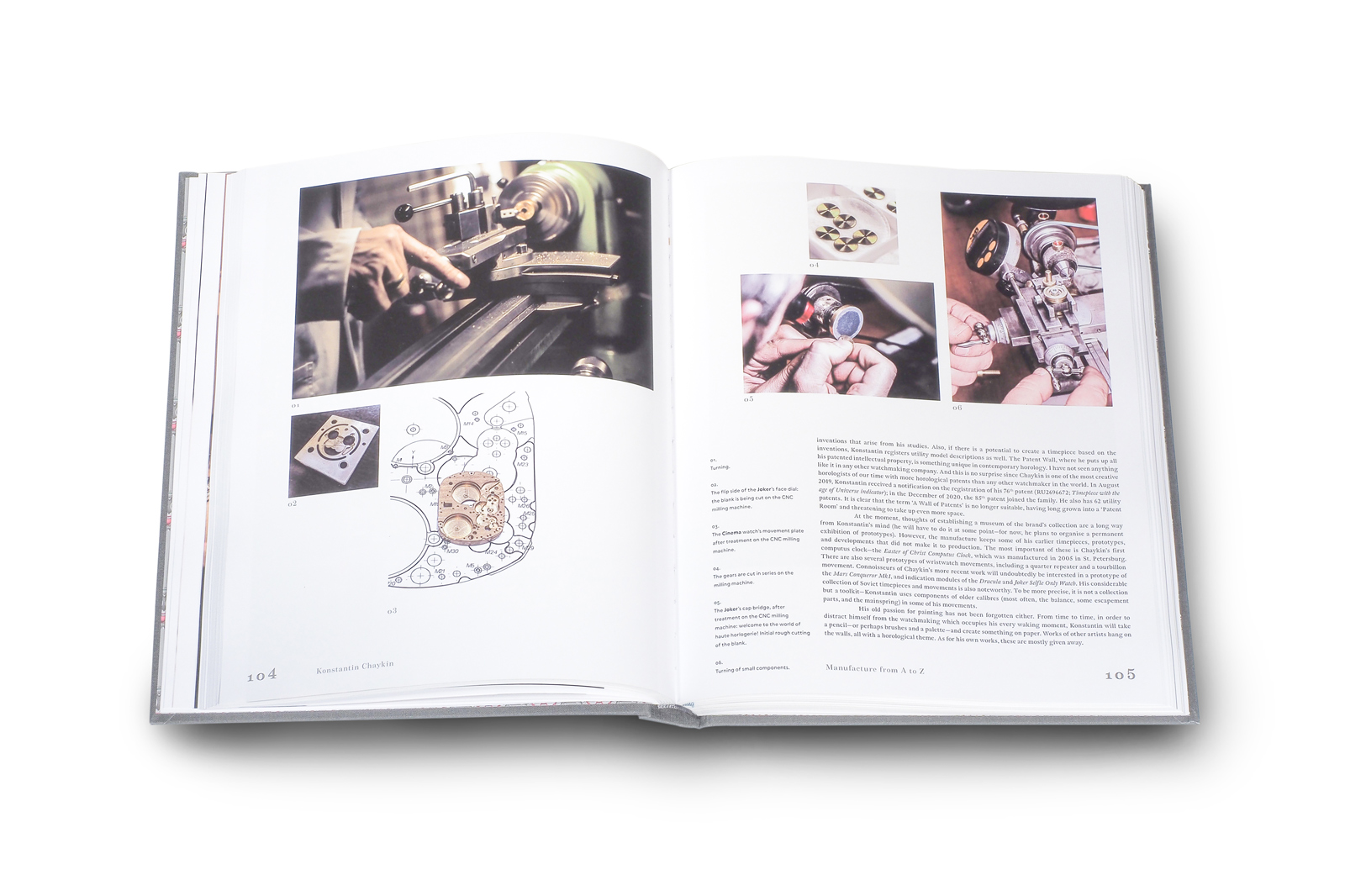

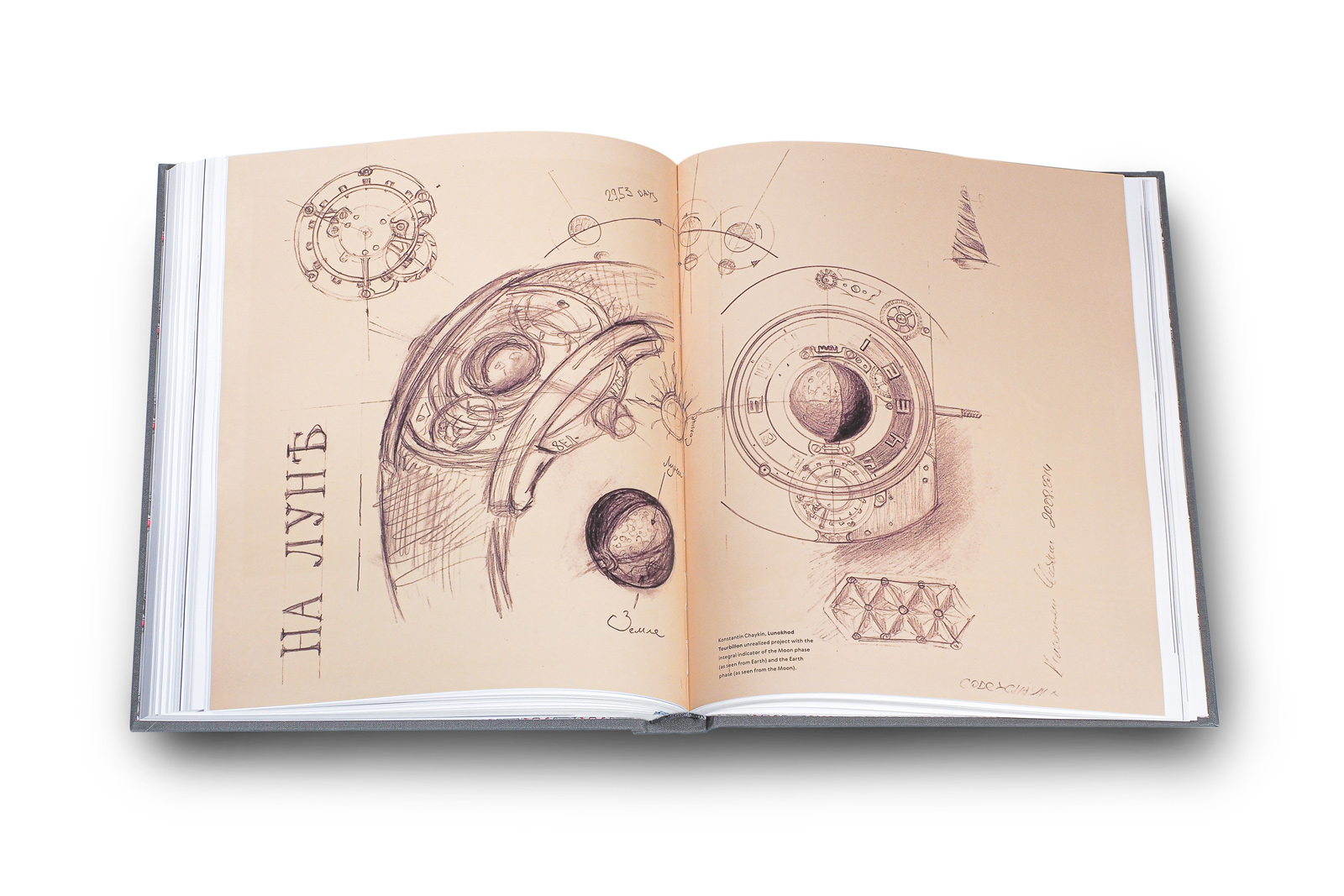

His drawings are now mostly destined for his Moleskine notebooks, where he notes down ideas for new movement constructions and watches. Konstantin’s illustrations have been reproduced throughout the book, showing how he develops ideas while proving that the designs are truly his own.

Scattered throughout the book are many hints that Konstantin would like to be seen as an inventor first and a watchmaker second. Listing all 85 of technical patents granted to Konstantin in a one chapter provides proof for his inventiveness – and an additional 62 design patents go unlisted. It is unlikely that another living watchmaker has ever so many patents to his name.

The patents also reveal Konstantin’s diverse mind. He works on one theme for a spell, most recently Martian time, before moving on to another. The book makes it obvious that his watches follow no house style but are each completely different, which does not necessarily help in the building of his brand.

The Cinema and Carpe Diem are typical of his works, each inspired by themes Konstantin found outside horology. Typical of Konstantin, but unusual for a watchmaker, is the fact that there are no customer commissions that spurred these original creations.

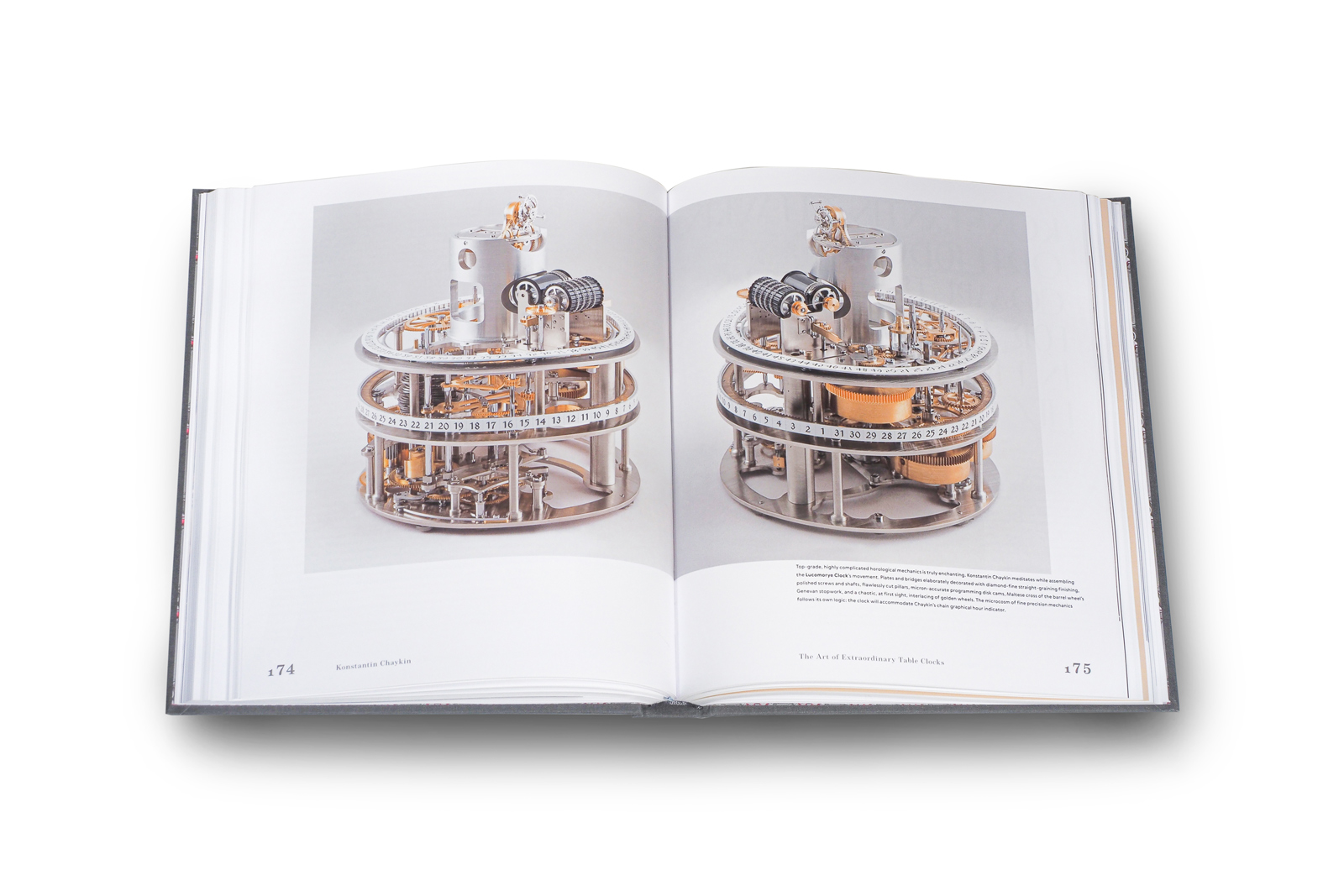

In contrast, Konstantin’s ultra-complicated clocks required a patron to finance the development. Amongst them is the Moscow Computus, a table clock shaped like Saint Basil’s Cathedral that incorporates all of the calendars that fascinate Konstantin, including the Orthodox Easter indication. The same fascination with calendars also reveals itself in his wristwatches, which feature the Hebrew and Islamic calendars.

Whether for watches or clocks, Konstantin had not only to design the timepieces, but also acquire the manufacturing know-how because he lacks the network of specialist suppliers that his peers in Switzerland and Germany can rely on. For example, early in Konstantin’s career, even rhodium plating for movement parts was unavailable in Russia.

The same can be said for growing his business. There is also no watchmaking school in Russia, so Konstantin had to train his employees from scratch. The book reveals that Konstantin strongly encourages his employees to take their own initiative to become creative – he allows them to use the production facilities in their spare time – which emphasises his intellectual generosity, but simultaneously risking the loss of talent like Anton Suhanov, a former employee who eventually embarked on his own career.

Concluding thoughts

The design of the book was Mr Kutkovoy’s call. “I believe the layout should be performed by an artist”, says Mr Kutkovoy, adding, “I insisted we should work with [Russian artist] Varvara Alay; she has the perfect feeling for proportions and she finds fresh perspectives.”

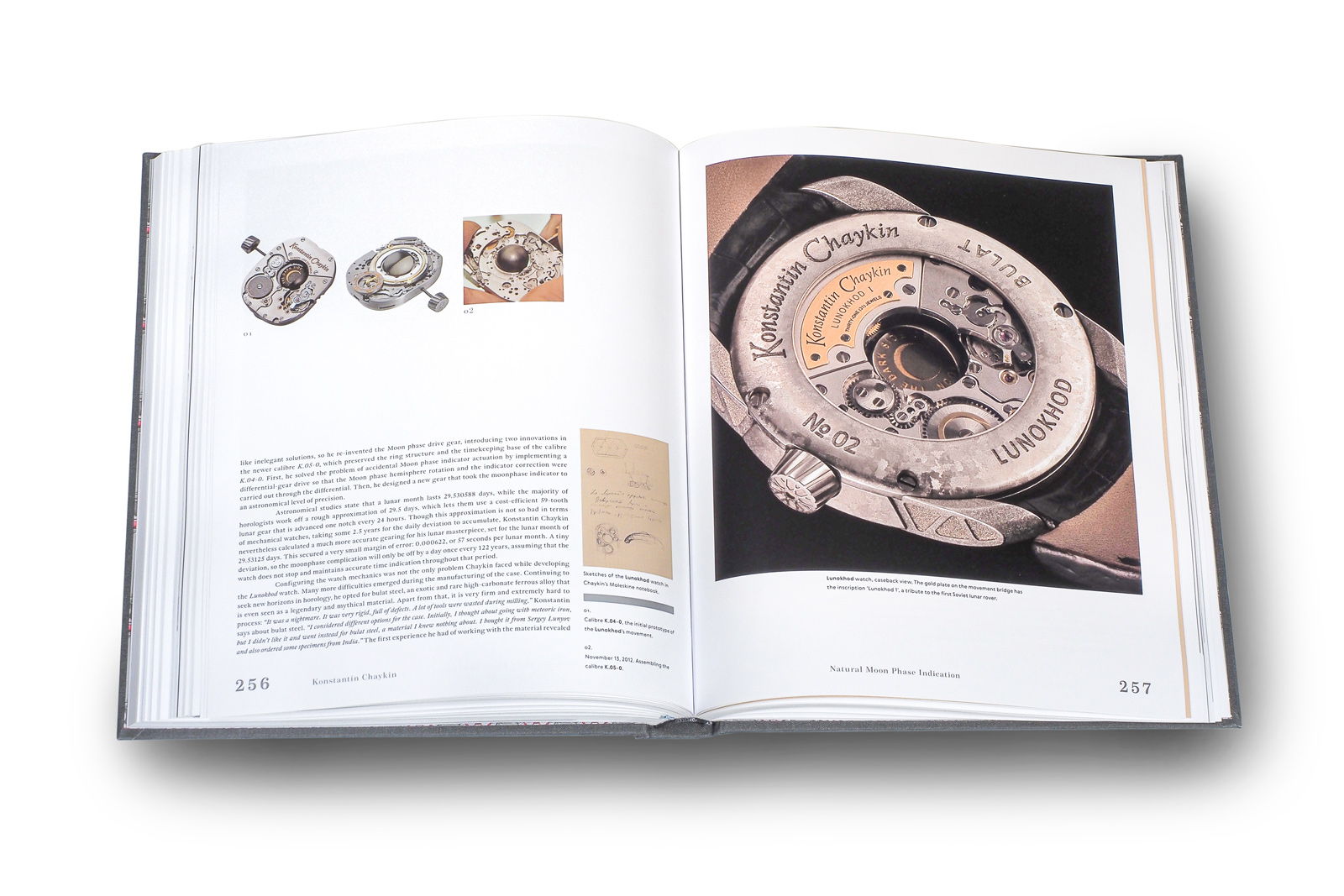

The book is well illustrated, with over 770 photos and drawings, often captioned in the margins. Sturdily bound in hardcover, the book’s pages are heavy, coated art paper with a satin finish and excellent printing. Like Konstantin’s watches, the tome is also mechanically well-crafted.

As for quibbles, they exist but are mostly minor. There is a lot of captivating information in the book, which matched with the smallish font size results in masses of dense text that can tax the reader’s concentration.

I would have bigger photos, with some images within not seeming to maximise the space available on the page. But I was told by the author that was not technically possible in some cases, as the photos of Konstantin’s earlier work was not of sufficient resolution for larger photos.

The catalogue raisonné could do with CAD drawings of the complicated mechanisms employed by Konstantin, in addition to the simple line drawings taken from patent applications. Such technical diagrams would satisfy the nerds amongst us.

A fan of Konstantin who is keen on detailed information on the watchmaker’s oeuvre, or more broadly an enthusiast who loves the unexpected and genuinely new, will all find the book a treasure trove. I hope more collectors use the book as an opportunity to go beyond the Joker and learn about Konstantin’s real watchmaking talent.

Beyond the specifics of Konstantin’s life and work, I also found the book to contain an abundance of information about the problems that independent watchmakers in general face. The fact that investors are not necessarily a solution to overcome financial and marketing shortcomings is concretely described in the book, illustrated by Konstantin’s own experiences. That’s a bonus the book offers, rare insight into the business workings of independent watchmaking, something usually hidden in watch journalism.

At €230, or about US$281, the book offers commensurate quality of content and compares well with its peers. Available to be shipped worldwide, it can be ordered directly from Konstantin Chaykin.

Correction June 6. 2021: The Moscow Computus is modelled on Saint Basil’s Cathedral, and not the Kremlin as indicated in an earlier version of the story.

Back to top.