Rewriting History – Discovering the Earliest Flyback Chronograph Wristwatch

The Longines 13.33Z from 1929.

As a collector, I find myself in the rather sparsely populated niche of observatory chronometers. Due to Longines’ unparalleled history in precision timekeeping, the brand became a long-standing, personal favourite. Notably, competition chronometer movements, like the 30B with its off-centre construction and the rectangular 360, strike all the right chords with me.

Along the way, I inevitably bumped into Longines’ outstanding in-house chronograph calibres – in chronological order, the 13.33Z, 13ZN, and 30CH – which opened a new door away from my focused, chronometer-centric journey as a collector. And it also led me to a discovery that rewrites horological history, one that gives Longines the title of having produced the very first flyback wristwatch chronograph, as well as the first chronograph wristwatch with two pushers.

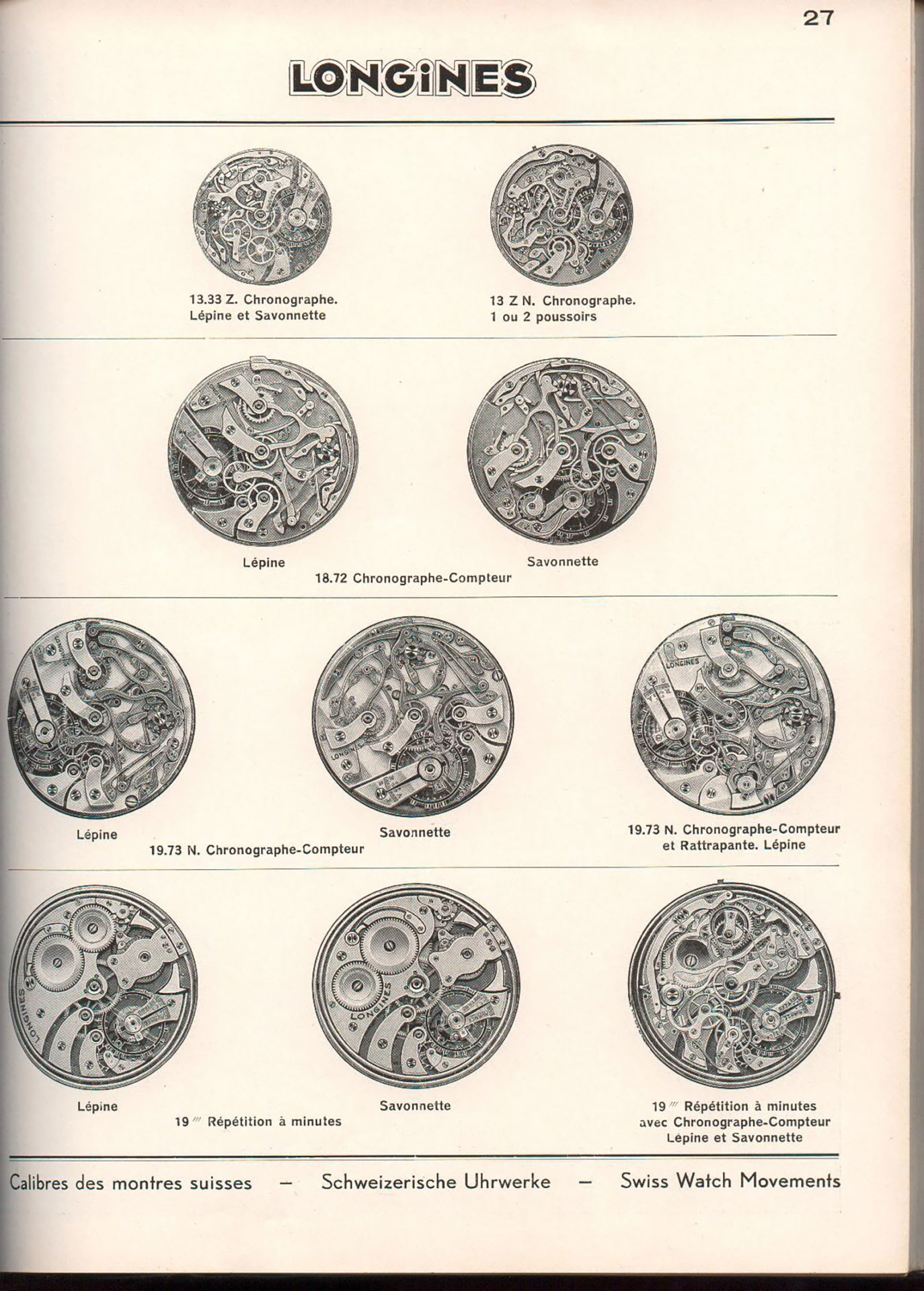

A catalogue page showing various Longines chronograph movements in the 1930s, with the topmost pair being for wristwatches, and the others for pocket watches

13.33Z

Though Longines had produced several remarkable wristwatch chronograph movements, a two-pusher flyback chronograph powered by the 13.33Z had become the object of my desire. A watch that was only produced in minuscule quantities and remains largely unknown to even the most discerning of collectors, with only eight examples known the market. A long and winding quest ensued that ultimately resulted in the opportunity to acquire an exceptional example from a private collection in Germany. That particular piece was tucked away for over a quarter-century, well hidden from the all-seeing eye of the internet and social media.

It was clear from the get-go that I was looking at an extremely early example of the 13.33Z with a flyback function, but little did I fathom its horological significance, which would reveal itself after more research.

Instantaneous, jumping minutes

Chronograph connoisseurs consider this unsung variant of the venerable 13.33Z as the technical pinnacle of vintage wristwatch chronographs, excluding more complicated split-second movements. The reason behind that is rooted in the technical merits of the movement, but also the fact that its development was well ahead of its time.

Most wristwatch chronograph calibres, including Longines’ fabled 13ZN or the well-regarded Valjoux 72, feature what is widely known as the semi-instantaneous minute recorder – the elapsed minutes hand creeps forward ever so slightly before it jumps to the next minute marker. In contrast, a true instantaneous minute hand that jumps with a crisp snap was historically only found in high-grade pocket watches.

However, the 13.33Z – introduced in 1913 as one of the first wristwatch chronograph movements – retained the sophisticated instantaneous-jumping mechanism found in pocket watches. Ultimately, the complex mechanism fell victim to cost-saving measures, and subsequently, the semi-instantaneous, or even less refined “dragging”, indicator became the de-facto standard for mass-produced chronograph wristwatch movements.

Naturally, the advantage of an instantaneous jumping minute recorder might appear negligible, more of an intellectual exercise in watchmaking than a solidly practical feature. However, one needs to keep in mind that the minute-change sequence of a semi-instantaneous chronograph – where the minute-register hand moves from one hashmark to the next – can take up to three seconds.

If a semi-instantaneous chronograph is stopped in the vicinity of a full, elapsed minute, it is often unclear whether the hand has already moved forward or not, leading to potential ambiguity in reading the elapsed time. A true instantaneous, jumping minute recorder completely eliminates the problem – giving it a tangible advantage in time measurement.

Flyback

Early chronographs with the 13.33Z featured a co-axial mono-pusher on the crown that controlled the chronograph function, and were either pin- or stem-set. Later examples had the single-pusher at two o’clock and were uniformly stem set. An exceedingly low number of 13.33Z movements were equipped with an additional flyback function, an upgrade that required a more sophisticated two-pusher configuration.

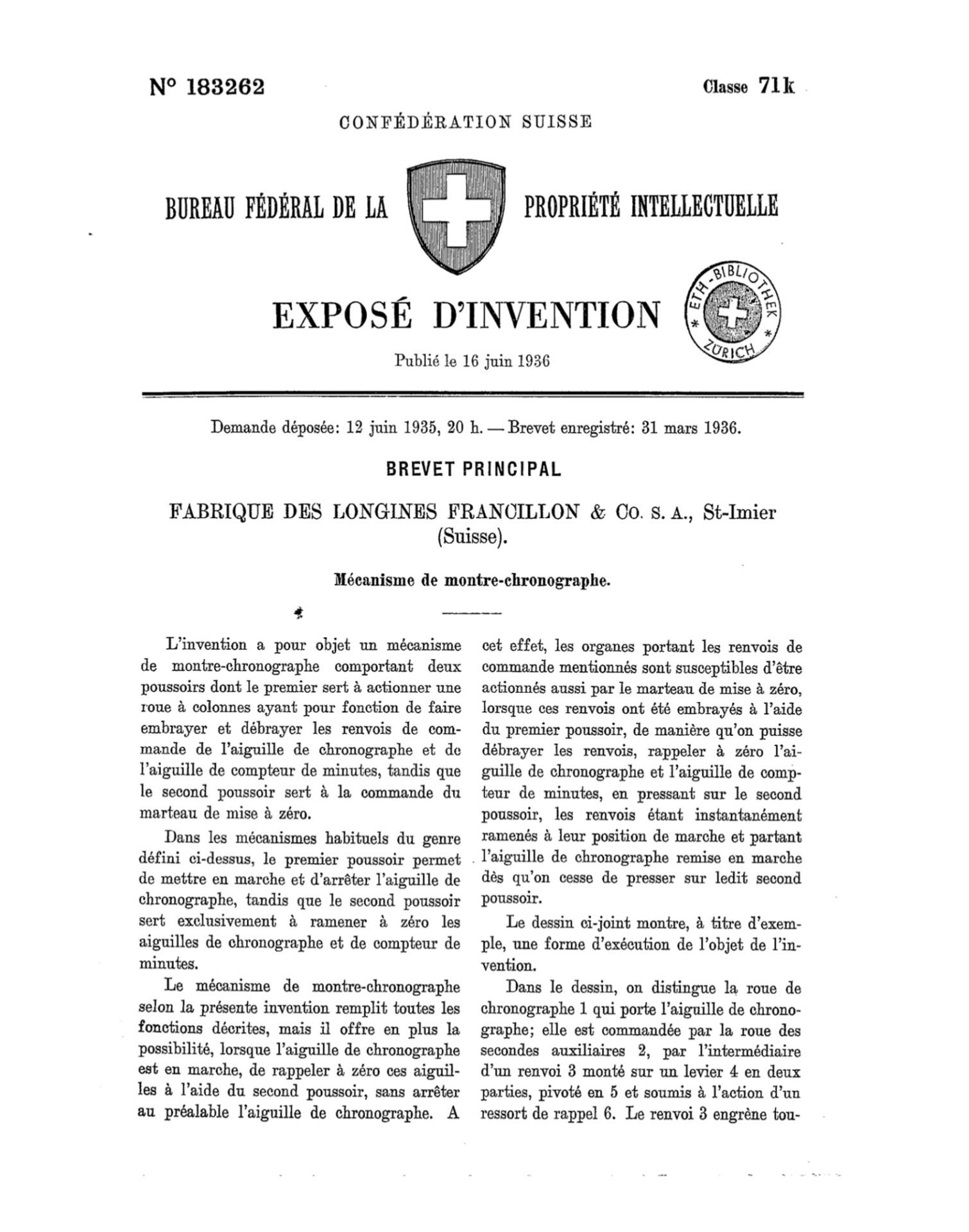

Longines filed a Swiss patent for the flyback mechanism on June 12, 1935, and the patent was granted March 31, 1936 as Brevet 183262. Interestingly, the present watch predates the patent application by an astounding six years.

The half-dozen years between production and patent indicates that the 13.33Z flyback was a testbed for the flyback functionality, which was subsequently commercialised in its successor, the well-known 13ZN. The experimental character of the present watch can also be derived from the location of the pushers. Upon closer examination, it is noticeable that the four o’clock pusher sits closer to the crown than the two o’clock pusher – an inevitable technical concession as a result of adding a novel function to an existing movement layout.

Swiss patent 183262 granted to Longines for its flyback mechanism, which depicts a modified Valjoux 22GH ébauche, referred to as the cal. 15”’ by Longines

Ahead of its time

Considering that this example of the 13.33Z left the Longines factory in 1929, it accomplished several “firsts” in horology, thereby refuting various, widely-held notions:

- The first two-pusher chronograph wristwatch – Breitling claims to have introduced the first two-pusher wristwatch chronograph in 1934, a fact disproved by this 13.33Z.

- The first flyback chronograph wristwatch – this substantially predates Longines’ flyback patent from 1936, which was based on a modified Valjoux 22GH, hence refutes the notion that the Longines 13ZN of 1936 or Longines 15”’ movement, based on the 22GH ébauche and used by Longines after 1934, were the first publicly-available, flyback-chronograph wristwatches.

Further, the 13.33Z with flyback is the only-known wristwatch chronograph movement produced before the Quartz Crisis that features a flyback function in addition to an instantaneous minute recorder, a feat that was only accomplished in the modern-day by A. Lange & Söhne with the Datograph of 1999.

Regrettably, it has been claimed that the L951.1 housed in the Datograph was the only known wristwatch chronograph movement combining both features. Bear in mind that the Datograph was launched in 1999 – 70 years after the Longines saw daylight in a retail store window.

The inner case back of the 13.33Z chronograph wristwatch

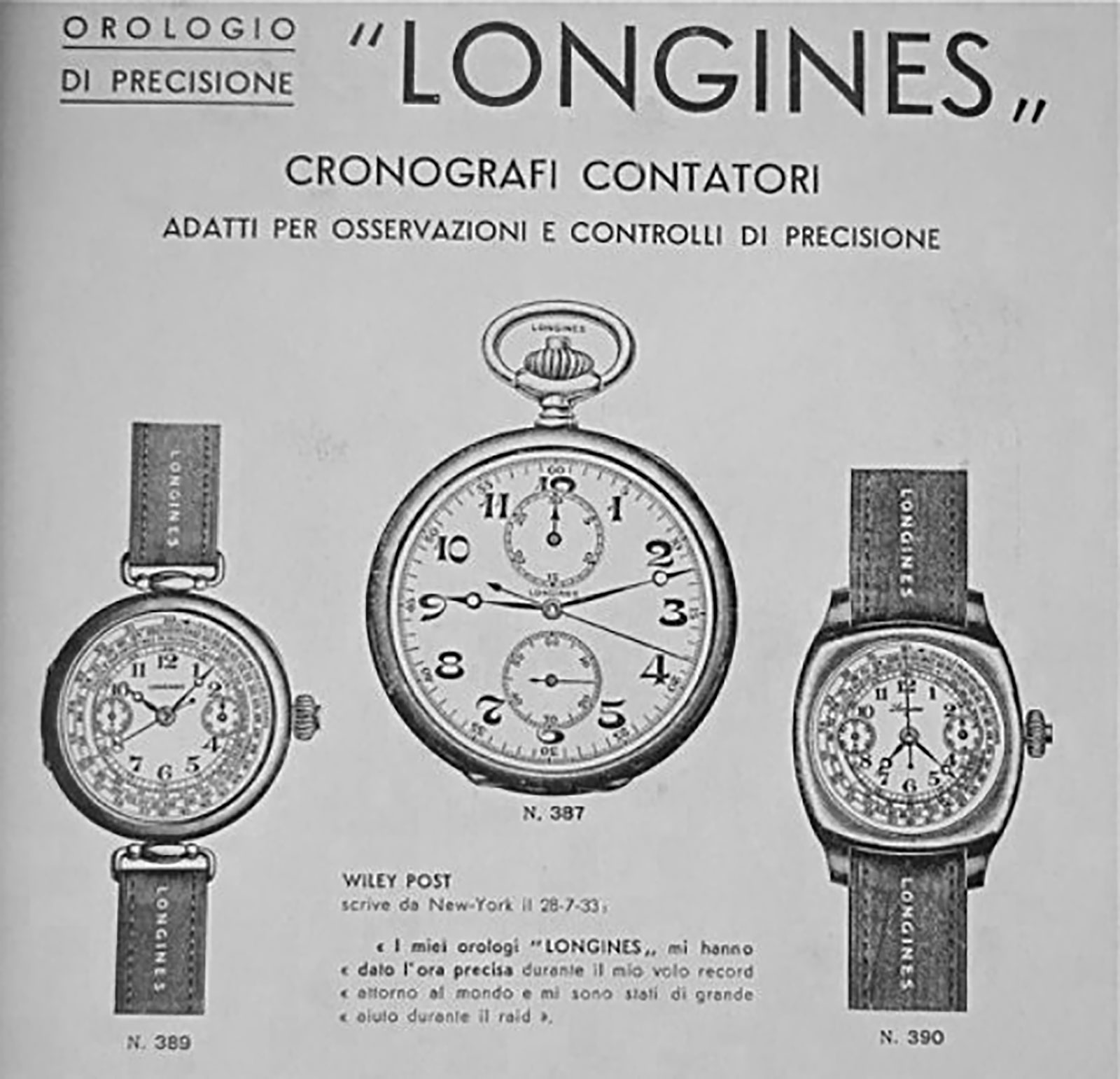

Not only were the inner workings of this wristwatch eminently progressive, but its external design was also very much ahead of its time. The 18k-gold case reveals a particular design language that only became commonplace several years later in the mid-1930s. This is especially evident in the shape of the thick lugs, which are very different from the thin, wire lugs that were practically standard for chronographs of the 1920s.

In contrast to the contemporary case, the multi-coloured and multi-scale enamel dial features a red “12”, a stylistic feature common in early wristwatches, notably First World War trench watches.

A 1933 advertisement for Longines showing a chronograph featuring a wire-lug case on the left

Historical record

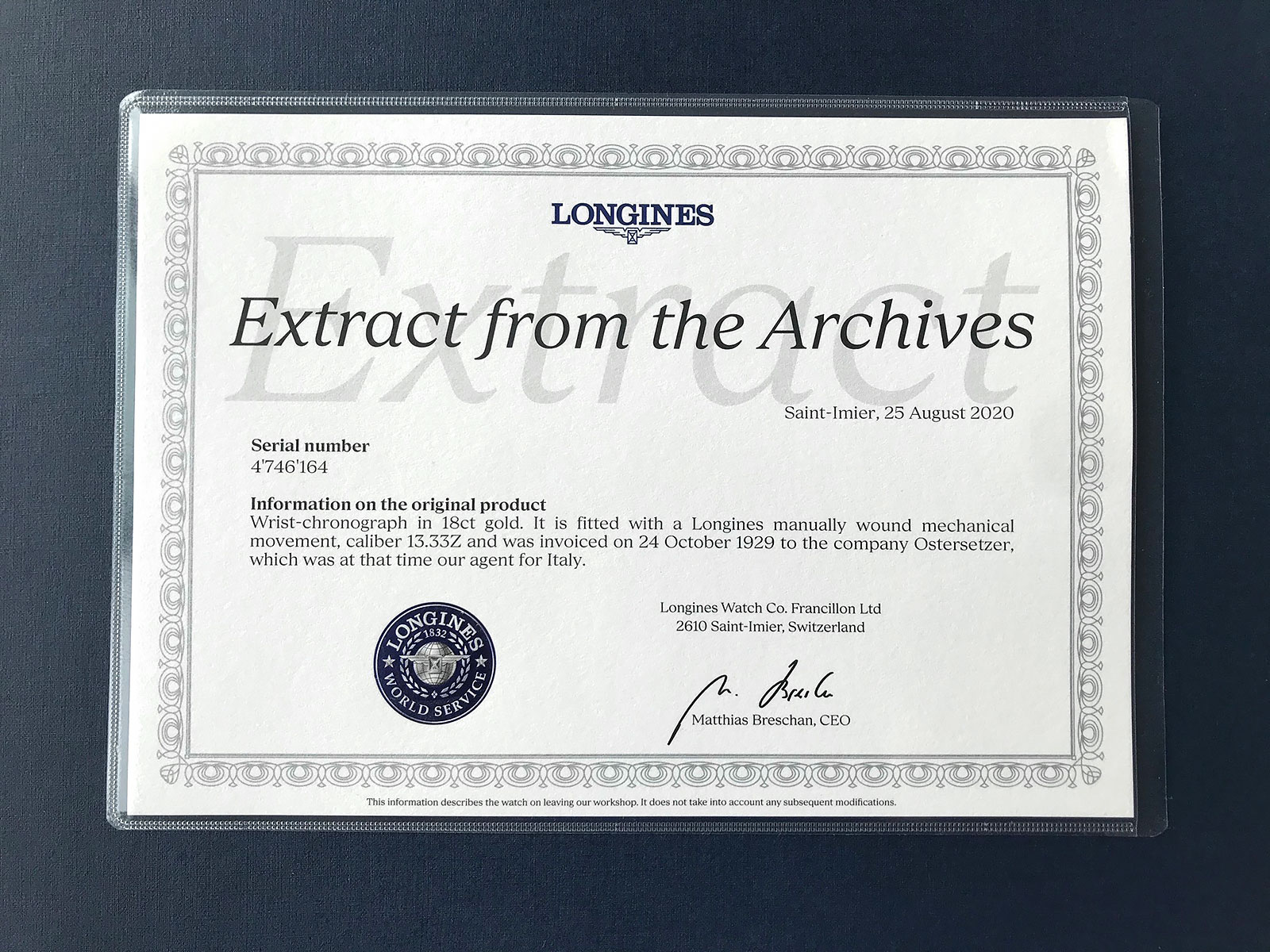

The Heritage department of Longines, with its world-class, complimentary service, managed to retrieve additional information from their vast archives: the chronograph was sold on October 24, 1929 to Ostersetzer, then an important Longines retailer in Italy.

Most importantly, the Heritage department confirmed this watch is the earliest instance of either a flyback or two-pusher chronograph they have encountered. Longines’ own well-curated museum possesses a two-pusher, flyback chronograph powered by the 13.33Z, but dating to 1930. This 13.33Z chronograph is a crucial piece of evidence that attests to Longines’ status as the pioneer in wristwatch chronographs.

Residing in Europe, the author is a medical doctor whose practice focuses on patients with hereditary diseases, while also conducting research in the field of human genetics. A collector and scholar focused on precision timekeepers, he launched the open-access Observatory Chronometer Database (OCD) in 2017. You can also follow him on Instagram.

Back to top.