Catching a Unicorn – The Seiko Gifted by the Emperor of Japan

A collector's tale.

I often get asked by family and friends: “Why vintage Seiko?”

I can trace my interest in this niche hobby to my childhood, coupled with the fact that I instinctively avoid the mainstream. Growing up in Saudi Arabia in the early 1980s, Japanese technology was found in the majority of products. When it came to watches, there were two market leaders: Casio and Seiko. Everyone at school, myself included, had a Casio of some sort.

Seiko watches, on the other hand, were worn by the working professional. I remember clearly being in awe of my headmaster’s watch. It was a Seiko that had a golden-yellow face with a sub-dial. I thought to myself that his success and authority must have come from the watch. I wanted that glorious watch that gave the headmaster his power.

Fast forward 25 years to 2017, and I noticed myself subconsciously buying retro Japanese technology, watching episodes of anime series Grendizer and looking for a vintage, yellow-dial Seiko watch – cue my pursuit of vintage Seiko and Casio.

The first vintage Seiko I bought was a yellow-dial, all-original ref. 6139-6005 “Pogue” – named after the American astronaut who wore one – from a well-known Seiko seller on Instagram. I had waited almost a year for a Pogue in original condition at a decent price, which frustrated me. After that, I wanted to jump the queue, so to speak, while being under the radar as I knew I couldn’t compete with many of the more serious Seiko collectors.

So I hatched a plan: trawl obscure second-hand sales sites and visit charity shops in small provincial towns that I happened to pass through. This strategy has yielded a handful of vintage Casio and Seiko watches, such as a 1977 Casio ref. 95QR-31 for £2 and a 1970 Seiko Actus ref. 7019-8010 for £5. As a result, my collection to date does not ascribe to a particular style, and is more a reflection of my luck and fascination for Seiko design from the 1970s.

The “Pogue”. Photo – the author

A unicorn!

In late April 2019, I was scanning listings on Gumtree, the largest classifieds site in the UK, for “Seiko”, expecting to see the usual fake Pogues and knock-off Seiko 5s.

An unusual advert caught my attention – “Grand Seiko 4580-7020”, price £0. I immediately clicked the thumbnail image to see a simple Seiko with a white dial, which although heavily stained, featured a flower emblem at 12 o’clock where the Seiko logo is usually found.

I was intrigued and quickly did an internet search for the model. The search yielded only a handful of hits from watch forums, mostly indicating that it was a very rare piece – a unicorn in fact – that was usually described as the “Imperial V.F.A.” (short for “Very Fine Adjusted”).

I contacted the seller to ask if the watch was available and the price. Almost instantly, he replied, “You have to come to see it in person and then make an offer”. It sounded like a scam. I deleted the opportunity from my mind.

A day later I found myself thinking, what if? So I contacted the seller again with a lowball offer of £200. The response was abrupt: “I have many buyers making me an offer much much more than yours, come see and make me an offer”.

I agreed and set a time and place for a meeting in Ipswich, a town two hours by train from my home in London and a place I had never visited before.

Making the deal

I messaged the seller on the day of the meeting, confirming my train journey to see him. I armed myself with a magnifying glass and a multi-purpose tool to inspect the watch. Along the way, I stopped at several cash points to withdraw wads of cash, sweating with worry that the seller would mug me.

I arrived at the destination, where a large man approached me and asked if I was waiting to buy a watch, to which I responded affirmatively. He asked me to follow him to McDonald’s to “make a deal”. We sat down in a quiet corner and he pulled out a clear plastic pouch containing a beautiful yet simple watch that emanated gravitas. I tried to keep my cool, deliberately looking blasé.

I took the watch out of the pouch to inspect it, and asked if I could unscrew the case back. He agreed and so I pretended to study the movement more closely – I was a complete novice then – hoping that the obvious water damage that I pointed out would put me in a stronger negotiating position. Over the course of the inspection, I deliberated an offer in my head that he could take seriously, while keeping in mind an upper limit that I would not go over, or else I would walk away. I threw the number at him.

He looked at me silently for 10 seconds or so, then reached out to shake my hand, exclaiming, “We have a deal!” I handed over the cash. Both of us looked relieved.

He surprised me with his honesty, asking that I take a photo of his driver’s license to qualify the legitimacy of the transaction. I wish all sellers were that honest.

We then had a short chat, during which he explained that as a truck driver, he frequents car boot sales across the UK, from which he bought the Seiko 4580-7020 “Imperial V.F.A.”. The seller had also told me that despite receiving many offers over the phone, I was the only buyer who had agreed to travel and see the watch in person. I can understand why that was the case, as we live in a society where everything is now delivered at a touch of a button and risk levels are managed remotely and electronically. I wish the seller well and more good luck in his travels.

Sleuthing

My excitement at owning an enigmatic Seiko watch was hard to contain. My first port of call was a Seiko forum where I got the contact details of an experienced, UK-based Seiko watch repairer to whom I sent the watch for servicing.

My second mission was to find out as much information about the watch as possible. This involved deep-diving into the web, following clues, Google-translating material in languages ranging from Japanese to Russian, while making contact with users across different forums and Instagram.

My stubborn nature paid off. I learnt that the Imperial V.F.A. shares the same cal. 4580 movement found in the Grand Seiko refs. 4580-7010 and 4580-7000. Moreover some of these movements were included in submissions to the Neuchatel Observatory for chronometer testing in the 1960s.

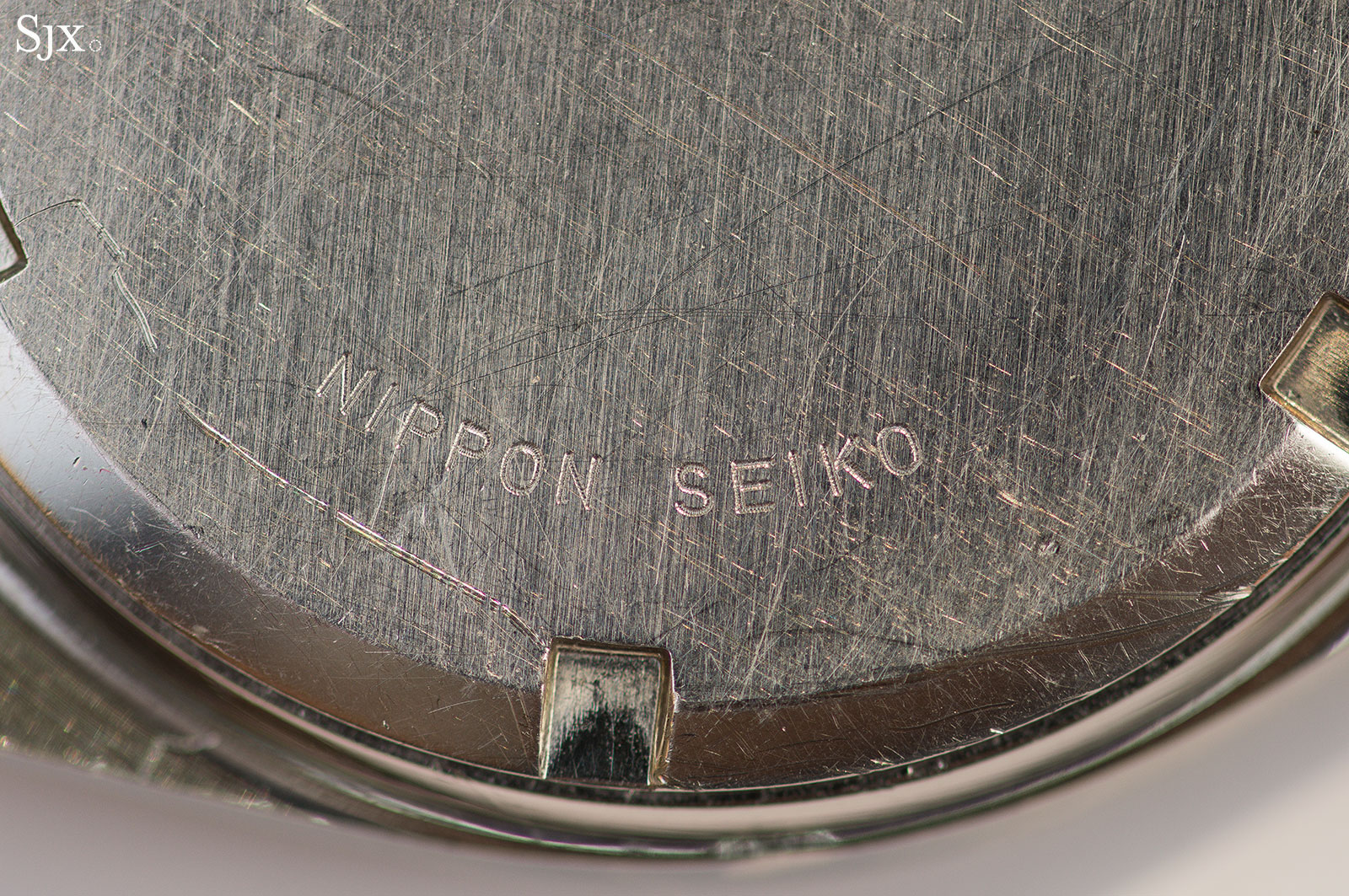

The case of the Imperial V.F.A. is the same found on the Grand Seiko ref. 4580-7010, apparently a very desirable reference. Apart from the dial, there are other differences when compared to its closest relative, the ref. 4580-7010. For one, the Imperial V.F.A. is not a “Grand” Seiko as advertised by the seller on Gumtree, instead the case back is almost bare, engraved with only “Nippon Seiko”, while the crown has no Seiko emblem.

I received a series of photos of the disassembled watch from the watch repairer, one of which was an image of the back of the dial, with a telling “1.6” stamped on the reverse. I was informed that was a manufacture date stamp indicating June 1971, which was also the month the watch was assembled. The date was an important finding that I will expand on below.

Showa Emperor

In parallel with my research about the watch, I wanted to know more about its connection to the Japanese Imperial family. The dial clearly bore the Imperial Seal of Japan, a chrysanthemum with 16 petals.

While that was obvious, I found little else on the internet about this mysterious watch. I resorted to contacting the Seiko museum in Japan for more information. One week later I received a response:

“These are the information [sic] we have on your watch:

- This watch with the Imperial seal flower on the dial is the watch Japanese emperor [Hirohito] used to give.

- For the one with the caliber 4580, it seems that Showa Emperor went to Europe for the first time in 1971 and gave this watch to the people who took care of him during this trip.

- This watch with the Imperial seal flower was not for sale.

- We have no record of the numbers of this watch SEIKO produced.

- The caliber 4580 was also sold as the Seiko Astronomical Observatory chronometer model which means this caliber 4580 passed the Swiss Neuchâtel Chronometer. Therefore, very high accuracy.”

A Seiko enthusiast highlighted that the final point is unlikely, as all cal. 4580 movements that passed the Neuchatel Observatory chronometer trials have been accounted for. Otherwise the information is clear – the Japanese Imperial household commissioned a number of Seiko 4580-7020 watches as gifts for the Emperor’s European hosts and dignitaries.

As I bought the watch in the UK, it makes sense that this watch was a gift from the Emperor Hirohito to a British host during his 1971 visit to the UK on October 5-8. Despite being a mere three days, the trip was a watershed moment for Japan as it reemerged after the Second World War, being the first overseas trip by the Emperor, who was greeted by large, albeit quiet, crowds.

With the historical events well established, a timeline becomes apparent: the watch was produced in June 1971, shortly before the Imperial visit to the UK in early October of the same year. And almost 50 years later, I have come to own it.

Collectively the information provides context to the design of the watch. It can be inferred that the watch was designed with the Imperial Seal taking precedence over everything else. The seal replaces the Seiko logo, which is instead executed in an unusually small print at six o’clock.

And as a state gift, the case back is appropriately engraved with “Nippon Seiko”, rather than the customary “Seiko Japan”. “Nippon” being the most formal Japanese name for the country and one that is used on currency and at state events. At the same time, the watch has neither no serial nor movement number, emphasising its status as a watch from the Emperor, rather than something manufactured by Seiko.

A rare beast

Given that Emperor Hirohito gifted the Imperial V.F.A. to his European hosts, it seemed likely that other documented examples exist.

As far as I am aware, there has been only one other known example of the watch, and it was offered for sale at a Japanese vintage-watch shop between 2004 and 2007, based on information given to me by a Seiko enthusiast who was interested in purchasing the watch. I have contacted the shop several times for information, without any response.

I would speculate that there are other examples locked in government vaults in various Europe countries due to rules prohibiting the acceptance of gifts whilst on official duty. Oh, to be a fly on the wall in those vaults! That leaves the tantalising possibility that another example of the Imperial V.F.A. may surface in a random corner of the internet.

I have had many offers from Seiko and Japan history enthusiasts for the Imperial V.F.A., which I have politely declined. As for the million-dollar question – what is the Imperial Seiko V.F.A worth? I could only speculate that it may achieve the same value as its close relative, the Grand Seiko V.F.A. ref. 4580-7010.

And the next project

I doubt I will ever be this lucky again, as I am certain I have spent all the luck allocated to me by the Seiko gods, but I do have a project that I am semi-actively pursuing.

The Imperial Seiko V.F.A. find has inspired me to collect other examples of Seiko watches that have a link to a ruling family. I currently have in my sights the Seiko ref. 7005-8140 dive watch made for officers of the Imperial Iranian Army during the reign of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. The market is currently flooded with fakes, so finding an honest example at a decent price is going to require patience and discretion.

I have learnt an incredible amount through the Imperial V.F.A., as well as broader topics from Japanese Imperial history to watch mechanics. The journey has been fascinating to say the least, introducing to me other enthusiasts whose passion for vintage Seiko has translated to invaluable support when I needed it.

I am grateful to these gentlemen for sharing their Seiko knowledge: Christopher Huang, Anthony Kable, and Gerald Donovan.

Back to top.