Grand Seiko introduces the T0 Constant-Force Tourbillon Movement

A concept movement with ambitions.

A tourbillon is not uncharted waters for Seiko, as evidenced by the Credor Fugaku Tourbillon of 2016. The extremely rare, and modestly unattractive, Fugaku was something of a statement, as much about its ornate case and dial as the mechanics.

Now an independent brand after being spun off from its parent, Grand Seiko has just announced a movement that squarely emphasises on timekeeping, the T0 Constant-Force Tourbillon. Announced as a concept movement – with no plans for commercialisation publicly revealed – the movement is Grand Seiko’s first equipped with a tourbillon, and also marks the first time Seiko or any of its brands is utilising a constant-force mechanism.

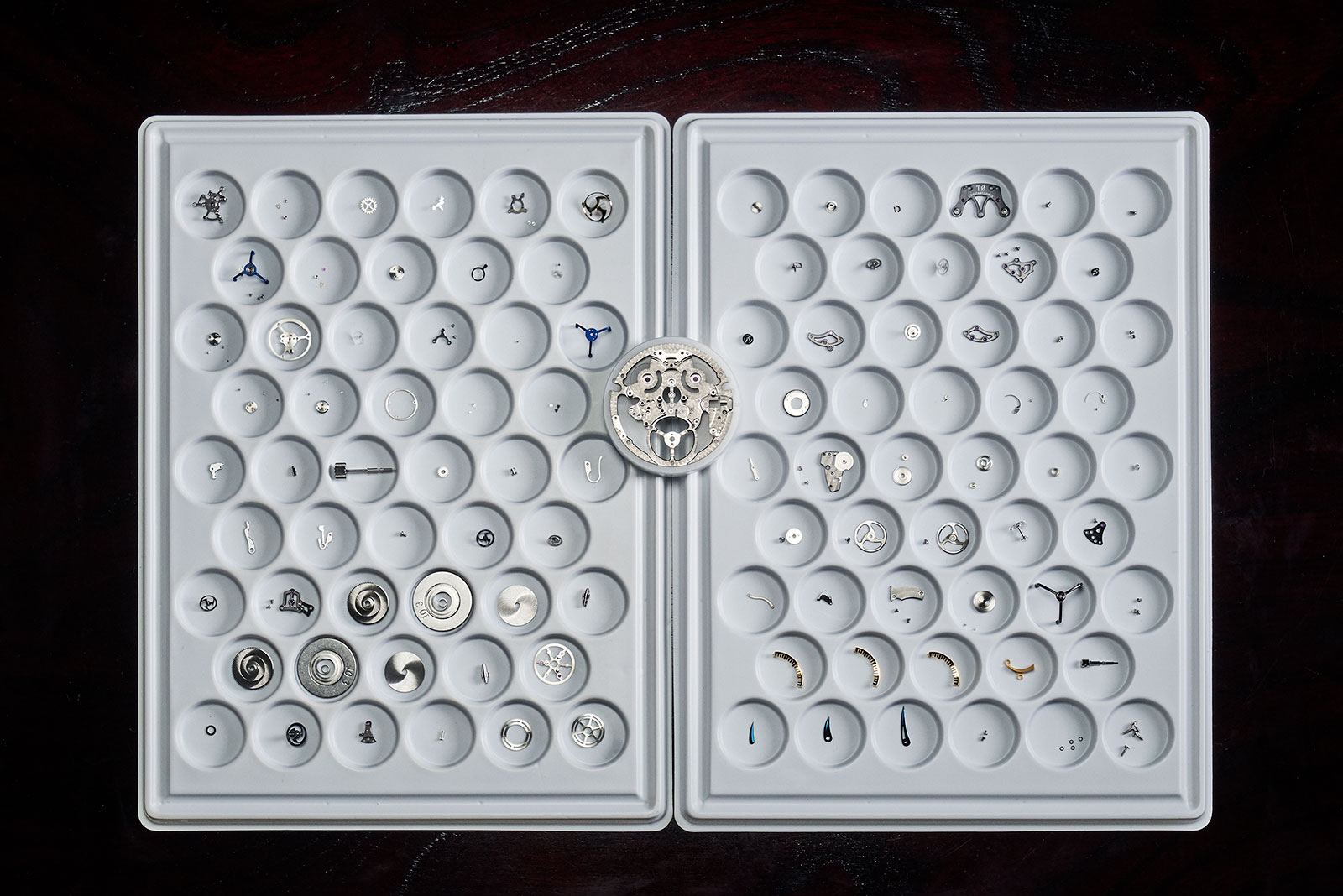

The T0 disassembled

Initial thoughts

It is not often Grand Seiko launches a new and truly novel movement; this year has seen a few. The recent 9RA5 Spring Drive and the 9SA5 Hi-Beat automatic are interesting and practical movements that will be found in future models. On the other hand, the T0 tourbillon stakes a claim of technical prowess oriented rather than practicality, a claim bolstered by the remontoir constant-force mechanism integrated in the tourbillon cage.

While Grand Seiko’s integrated remontoir constructed is patented, this is not exactly novel. Precedents in the watches of IWC and Andreas Strehler, for instance. While each of these executed the idea of an integrated constant force differently, all share the common approach of a one-second remontoir. In short, the Grand Seiko construction is a new, and perhaps better, interpretation of a familiar idea.

As a concept movement, it is possible variations of the T0 will be commercialised, or the technology might trickle down to more affordable watches.

But despite being presented as a concept movement, the T0 is characterised by outlandish design elements that feel forcibly incorporated after the fact – seemingly to make the audience sit up and take notice of the form rather than substance – rather than being an integral part of the design. Most notable are the shape of the bridges; the curved, fang-shaped hands; the wide arms of the tourbillon cage and even the proprietary turret-headed screws – all of it feels a touch excessive from a brand that has always been far from the likes of Jacob & Co. in style.

The Credor Fugaku Tourbillon

Constant-force nested cages

The highlight of the movement is the tourbillon cage, which integrates a one-second remontoir co-axially, meaning the constant force mechanism shares the axis of the tourbillon. It can be inferred development of the constant-force tourbillon began about a decade ago, as its patent, JP2015072254A, was filed in 2014.

The tourbillon consists of two three-legged cages made of blued titanium, nested within each other. The inner cage rotates beats with a constant force from a spiral remontoir spring, sandwiched between the cages and hidden from view.

The outer cage incorporates a five-toothed ceramic ratchet wheel, which is released every second by the inner cage’s rotation. The release of the ratchet wheel in turn releases the outer cage, which jumps a second forward – doubling as a deadbeat second display – and simultaneously recharging the remontoir spring.

As with current high-frequency Grand Seiko movements, the escape wheel of the T0 is fabricated via an ultraviolet lithography process that results in a delicately skeletonised shape intended to reduce inertia and weight. This is coupled with a relatively small balance wheel that beats at 4 Hz, or 28,800 beats per hour, higher than the 2.5 Hz or 3 Hz of most tourbillon movements.

On the reverse, clearly visible are the two parallel barrels that occupy the top half of the movement. The left barrel has visible planetary gears that act as a differential for the power reserve display at nine o’clock.

The barrels power the going train via the centre of the movement – the hand sit in-between the two barrels – while driving the tourbillon cage on its periphery. This contrasts with conventional tourbillons, which are often driven from under the cage, a construction that would make what appears to already be a bulky movement even thicker.

Identity crisis?

The rest of the T0 is heavily designed, featuring open-worked, skeletonised bridges that are a departure from the graceful norms of high-end Grand Seiko and Credor movements. Those movements are generally fitted with large bridges that hide most of the internals.

While the T0 has a mystifying design ethos, it is unquestionably intended to showcase the technical prowess of the mechanics by putting them on show; perhaps the serially-produced version of the T0 will return to the traditional Grand Seiko style.

More broadly, the movement also poses philosophical questions. It is an overwrought, highly-complex calibre of the sort that many Swiss watch brands – especially ambitious startups working with complications specialists – excel at. Swiss watchmakers have also been constructing such movements for a long time. It will be interesting to observe where Grand Seiko goes with the T0.

Back to top.