A Detailed Look at the Magnificent Philippe Dufour Grande and Petite Sonnerie Wristwatch

Philippe Dufour was the first watchmaker to put the most complex of complications into a wristwatch with his grande and petite sonnerie of 1992. Here's a close-up, exhaustive examination of one of these extraordinary timepieces.

A week ago we went up close with an extraordinary, 100-year old grande and petite sonnerie pocket watch, one of just ten Patek Philippe made. Today we take a detailed look at its modern equivalent, the first ever grande and petite sonnerie wristwatch, made by the great Philippe Dufour. He is best known for the brilliant Simplicity (a watch that made headlines again recently), but Dufour’s masterpiece is undoubtedly the grande and petite sonnerie, a complication that chimes the time as it passes, just like a grandfather clock.

The history

His work on the grande sonnerie began with a series of five pocket watches he made for Audemars Piguet starting in 1982, with the last one delivered in 1988. Though Dufour produced the entire movement of each grande sonnerie pocket watch, his name was absent from the timepieces. That anonymity drove him to work on his own timepieces in the late 1980s, becoming one of the earliest independent watchmakers as we know them today.

Dufour introduced his ever grande and petite sonnerie wristwatch at Baselworld 1992, becoming the first watchmaker to incorporate the complication in a wristwatch. That same year he came a member of the Académie des Horlogers et Créateurs Indépendants, the association of independent watchmakers better known by the acronym AHCI.

The original series of grande and petite sonnerie wristwatches consisted of four watches. All fitted with white enamel dials featuring Roman numerals and Breguet hands, while the cases were in each of the three colours of gold as well as platinum. These were produced over several years, until the late 1990s.

|

| Grande and petite sonnerie wristwatch in pink gold, no. 2 of the series |

Then in 1999, Dufour introduced his most avant-garde timepiece, the grande and petite sonnerie wristwatch with a sapphire dial. The entire striking mechanism was visible through the clear dial. Two were made, one each in white and rose gold. And more recently he completed two more, and is rumoured to be working on the ninth and last one that will be equipped with the last ebauche, or movement blank, remaining.

A striking masterpiece

Pictured here is the white gold grande and petite sonnerie skeleton dial wristwatch. Though its aesthetics are decidedly different from the typical Dufour style that favours mid-20th century Vallée de Joux watches, the movement is exactly the same as his other grande sonnerie watches. Despite being a remarkably complex movement, it was designed to be simple to operate. Turning the crown clockwise winds the barrel that powers the timekeeping portion of the movement, turning it in the opposite direction winds the barrel that powers the striking mechanism.

A button in the crown activates the striking mechanism on demand, while sides hidden underneath the hinged bezel are function selectors. Because all his grande sonnerie wristwatches were sold to English speaking clients, the functions are indicated in English. And they are naturally hand-engraved, and filled with a dark blue lacquer.

The watch can be set to silent or strike mode with the slide at 12 o’clock, while the slide at six o’clock puts the watch in grande or petite sonnerie mode. As the engravings indicate, in grande sonnerie mode it will strike both the hours and quarters on the hours and quarters, while in petite sonnerie mode it will strike the hours and quarters on the hours, and only the quarters on the quarters.

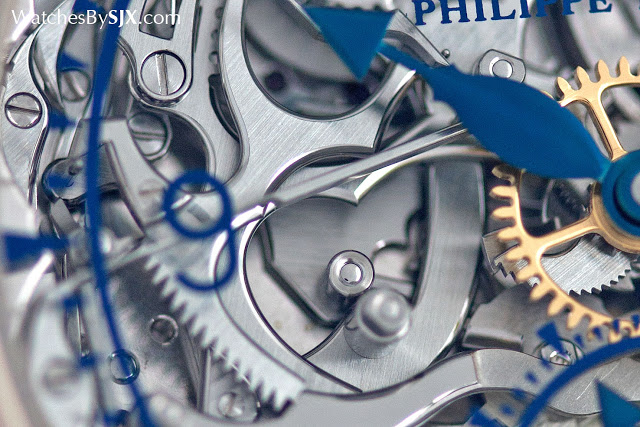

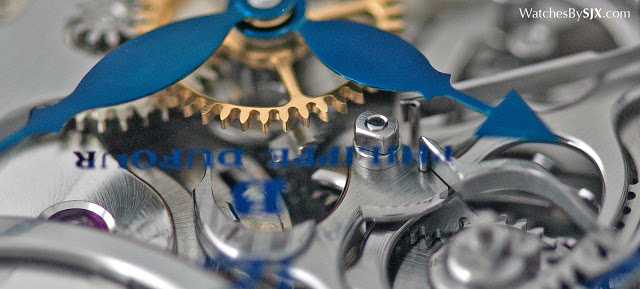

A sapphire dial with blue markings shows off the striking mechanism in all its glory. Oddly enough for a Philippe Dufour timepiece the sapphire dial is decidedly contemporary, with arrowhead markers for the minutes and seconds. And the hour and minute hands are somewhat bulbous.

But because the visible movement is such an overwhelming presence, everything else is barely apparent. In fact the rest doesn’t really matter. The detail of the movement is exquisite. Everything is properly finished. The steel parts of the striking mechanism, the racks and snails, are particularly lovely.

Did I already say everything is gorgeously finished?

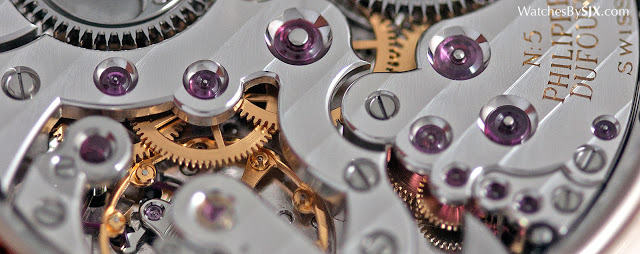

Needless to say, the view from the back is as good as it is from the front. The layout and construction of the movement is utterly traditional. It bears a striking resemblance to the grande and petite sonnerie pocket watches he made for Audemars Piguet, which in turn resemble early 20th century specimens.

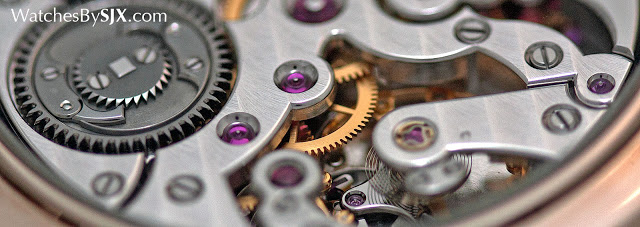

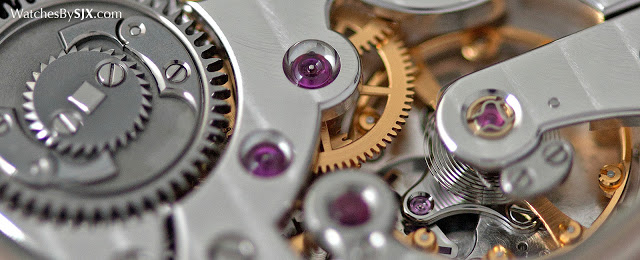

The movement is easy to understand. Looking at the photo below, the two barrels are located at 2 and 11 o’clock below, both featuring the grand sonnerie style winding click (the serrated gear with hooks connected to curved springs).

The barrel on the left powers the timekeeping mechanism, which has a free-sprung, adjustable mass balance (visible at seven o’clock). This feature is probably the only modern component of the movement, the rest of which could pass for a decades old pocket watch. And the barrel on the right powers the striking mechanism, with one of the hammers for the chimes visible at six o’clock. The other is hidden underneath the bridge with Dufour’s name.

Dufour is revered for his finishing, the manner in which he polishes the components of the movement. He does that very well, so well, in fact, that even Seiko sent its watchmakers to study with him.

|

| The bridges are rhodium plated brass and finished with parallel Geneva stripes; they almost glow |

|

| A close-up of the winding click – all its parts are made of steel and black polished, just like the escape wheel cock on the far right |

|

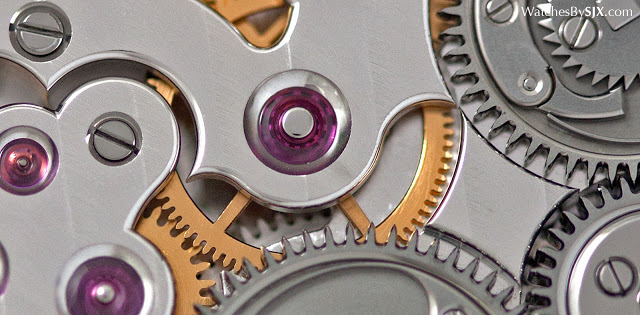

| Notice how all components are finished, even the spokes of the gilded gears |

|

| The incredibly sharp point of the bridge is finished by hand, done that way just to show it’s possible |

|

| The rounded, mirror-polished bevels and countersinks are so reflective they show the lens of the camera |

|

| Because the teeth of the barrel ratchet are polished, as is the recess for the ratchet, they reflect on each other |

But even gods are not above reproach, and so it is with this movement. The adjustable mass balance might not be the only modern element in the movement, the pallet fork and escape wheel (visible below at seven o’clock) also look modern, because they lack the refined finish of the rest of the movement.

Nonetheless, the Philippe Dufour grande and petite sonnerie is one of the most stunningly finished wristwatches of modern times. And of course it sounds as good as it looks.

Back to top.