Explaining The Breguet Tradition Chronographe Indépendant 7077 – Ingenious And Innovative Chronography (Original Photos & Price)

Just introduced at Baselworld 2015, the Breguet Tradition Chronographe Indépendant 7077 is equipped with movement that features a novel and genuinely interesting construction, including a chronograph that essentially powers itself.

Breguet marked at 10th anniversary of the Tradition at Baselworld with two significant complications, a minute repeater and the Tradition Chronographe Indépendant. The Tradition chronograph takes an existing idea in watchmaking – a separate power source and oscillator for the chronograph – but executes it in a wholly new and ingenious manner.

A power of its own

Traditional chronographs, including the best of them like the Lange Datograph or Patek Philippe calibre CH 29, are comprised of a base movement with a chronograph mechanism on top. When started the chronograph mechanism engages with the gear train of the base movement, giving the chronograph the energy necessary for its operation. There are several variants on this, ranging from the horizontal coupling found in traditional constructions to the vertical coupling that it is popular today, but fundamentally they operate on the same principle; the chronograph does not have its own power source.

Naturally the alternative is to give the chronograph its own power source, much like how a grand sonnerie has an additional barrel to power the en passant striking mechanism. That has been done before, an example includes the Jaeger-LeCoultre Duomètre à Chronographe. Breguet, however, has done it differently. The Tradition Chronographe Indépendant has a power source, gear train and oscillator for both the chronograph and timekeeping mechanism, essentially two movements in one watch.

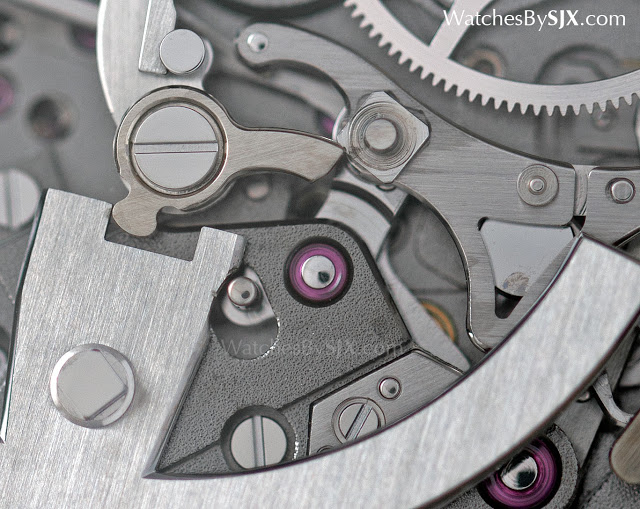

What is notable about the chronograph mechanism is how it has been constructed. Instead of a mainspring (a long, coiled strip of metal) as is traditional, the chronograph is powered by a blade spring. A thin strip of steel with a slight kink, the blade spring is cocked when the chronograph is reset, meaning the chronograph powers itself. This puts enough tension in the spring to power the chronograph for 20 minutes, a short but sufficiently useful period of time – timing eggs is the oft cited cliche. The scale at 11 o’clock measures elapsed time.

|

| The 20 minute chronograph scale is also shown on the back |

The advantage of a blade spring is its size, the spring occupies a narrow section of real estate at six o’clock on the back, as well as the fact that is can be wound up by a single push of the reset button. Pressing the button requires a bit more force than on a regular chronograph, but not significant enough to be an inconvenience.

Intriguingly, the going train for the chronograph is non-concentric, to account for the non-linear torque from the blade spring. Put simply, the blade spring delivers a lot of power at the beginning and much less as it winds down, which means the going train must account for that. Because the blade spring is always under tension – once the chronograph is reset the spring is cocked – the balance wheel for the chronograph is always ready to go.

Two brakes keep the chronograph balances stationary, but once the chronograph is activated the brakes release, and the balance wheel starts oscillating at maximum amplitude and 36,000 bph frequency almost instantaneously. This avoids errors in time measuring when the chronograph is just started.

The instant start of the balance wheel combined with the high frequency of the chronograph means it has a maximum error of 0.08 seconds for the 20 minutes it can run, less than the 0.1 seconds resolution of chronograph. That renders the error essentially negligible.

|

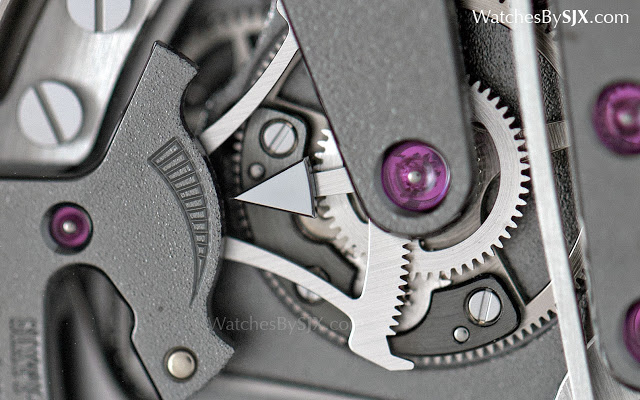

| A close-up of the anchor lever and cam |

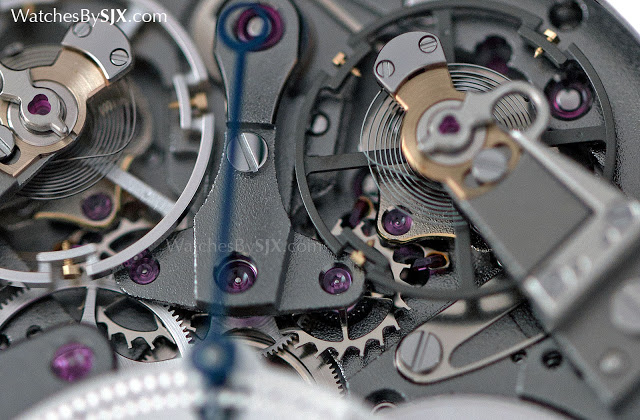

Due to the unusual chronograph construction, the chronograph is started by the button at four o’clock, but stop and reset at both accomplished by the button at seven o’clock. Pressing the buttons swings an anchor-shaped lever, linked to a cam at its top-centre, that controls the chronograph. On the dial, a blued steel arrow at six o’clock indicates if the chronograph is running.

Movement symmetry

Even though the chronograph balance wheel (at seven o’clock on the dial) beats at 36,000 bph or 5 Hz, it is the same size as the timekeeping balance wheel that runs at 28,800 bph or 3 Hz. That conflicts with physics, as the faster a balance runs the smaller it should be.

|

| Being titanium, the chronograph balance wheel is dark grey |

However, the chronograph balance is made of titanium, making it significantly lighter than the timekeeping balance which is made of a conventional and heavier Glucydur alloy. This gives the dial a pleasing symmetry.

Silicon escapements

The timekeeping portion of the movement is orthodox in its construction. It has a 50 hour power reserve, indicated by the display at two o’clock. But like the chronograph escapement it is fitted with a non-magnetic silicon hairspring with a Breguet overcoil, along with a low friction silicon pallet fork.

|

| The power reserve for the time display on the back |

Ruthenium frosting

The Tradition Chronographe Indépendant sticks to the signature Breguet style, with a guilloche dial, pomme hands and a frosted movement finish. But the watch looks like a contemporary creation, primarily due to the dark grey ruthenium coating on the movement.

|

| Translates as “Swiss hand guilloche” |

Though the frosted finish is typical for Breguet, the grey coating gives it a completely different look from the traditional gold frosting. Several elements of the movement are taken from historical Breguet pocket watches, including the pare-chute shock-proofing spring and the anchor-shaped chronograph lever.

|

| The curved pare-chute spring that holds the balance endstone |

The 44mm case diameter also gives it a modern feel; on the wrist it sits noticeably large with long lugs. The size is large for Breguet, a brand typically associated with elegant timepieces, but suits the modern aesthetic.

The Tradition chronograph is available in white or rose gold. Prices are SFr77,800 or S$114,500 for the white gold, while the rose gold costs SFr77,000 or S$113,300.

Back to top.