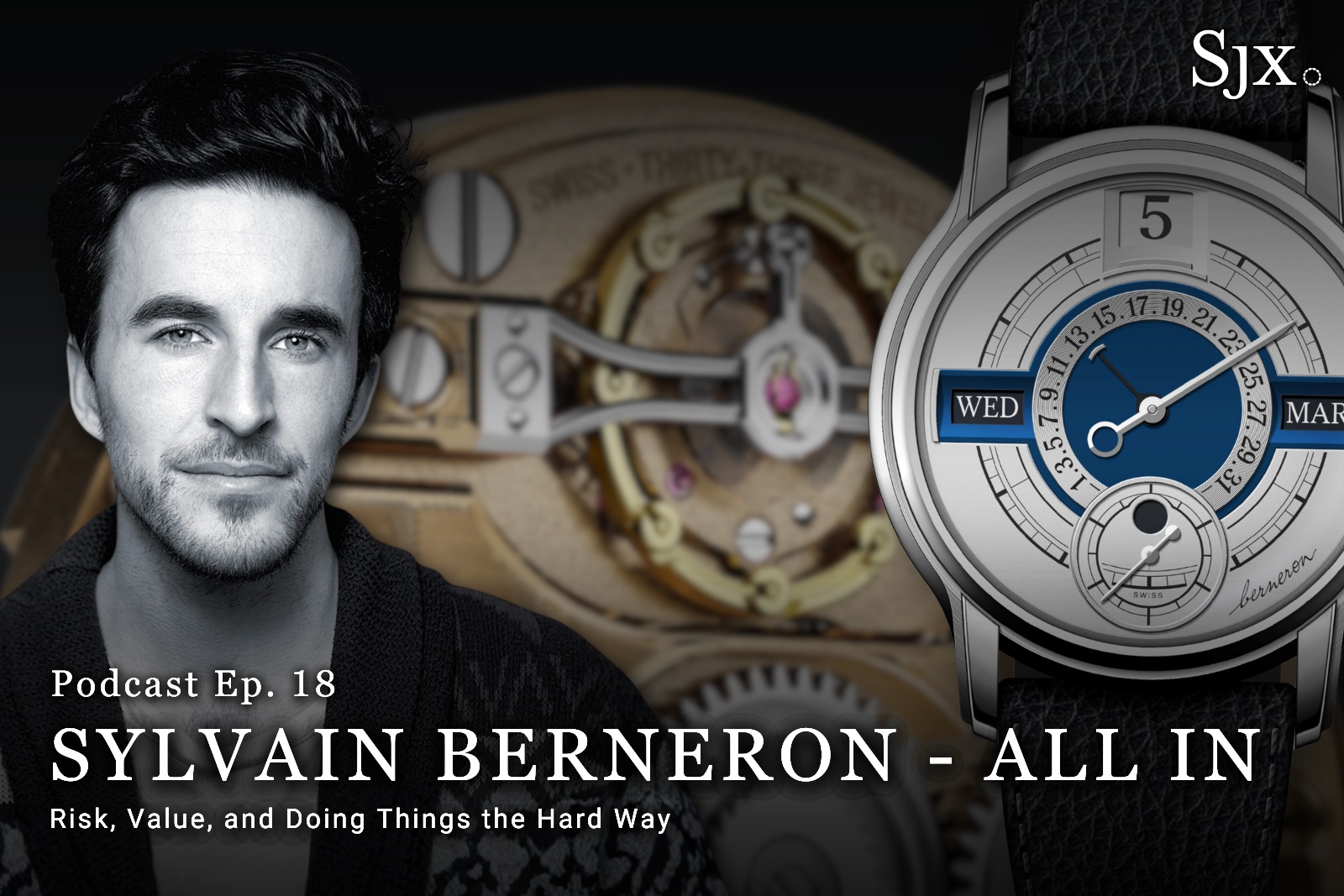

In-Depth: Patek Philippe Ref. 1518 in Stainless Steel

When steel is worth more than gold.

Many superlatives have been ascribed to what might be the most valuable watch this fall auction season – the Patek Philippe ref. 1518 in stainless steel. Headlining Phillips’ upcoming auction in Geneva, the steel ref. 1518 is paradoxically extraordinary and ordinary all at once.

As the first serially-produced perpetual calendar-chronograph wristwatch, the ref. 1518 is already a landmark Patek Philippe wristwatch, one that spawned a lineage that includes the refs. 2499, 3970, and 5970. And then there’s the ref. 1518 in steel – only four are known.

The steel ref. 1518 has rarity, historical importance, and an eight-figure value; but on the wrist, this “holy grail” is compact, lightweight, and monochromatic, discreetly low-key.

At a diminutive 35 mm in diameter, the ref. 1518 is small by today’s standards. The watch doesn’t look like much on the wrist from across a room; in fact, it isn’t immediately obvious to a layperson (or even a casual watch enthusiast) that the watch is worth more than most houses and vintage Ferraris.

Yet the ref. 1518 in steel is appealing for many intellectual reasons: extreme rarity, historical lineage of the perpetual calendar chronograph, even sheer value. This is a trophy in many senses.

Historically, the ref. 1518 was important even in its time. It was once Patek Philippe’s most complicated regular production wristwatch, and the steel ref. 1518 was likely the most expensive steel Patek Philippe when it was in the catalogue.

Part of its appeal also lies in the contradiction of its tangible “normalcy” and extreme desirability. The steel ref. 1518 is modest on the wrist, and might be casually worn in a large European capital without fear, certainly more so than a luxury sports watch. But this example of the ref. 1518 was once the most expensive wristwatch ever sold at auction, when it achieved almost US$11 million with fees in 2016.

Ordinary alloy, exceptional watch

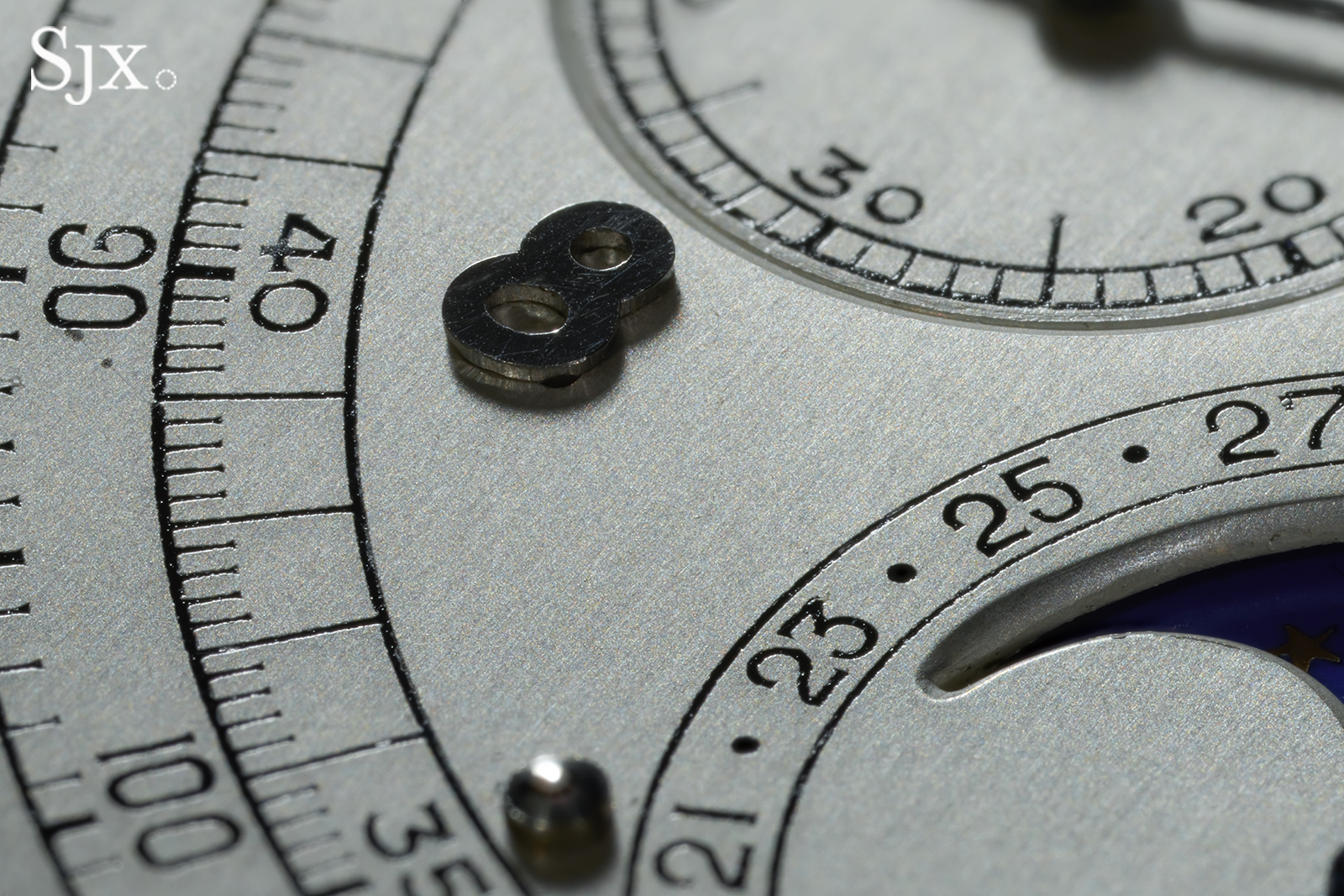

In the hierarchy of ref. 1518s, the steel version is the one to have (with a great “pink on pink” coming in second). Despite the rarity, all four known examples are well documented.

More than just the material, the four steel ref. 1518s are subtly entirely different in terms of case form and design compared to their gold counterparts – and three of them are different from the last example.

The differences are due to different makers for each case type. The gold cases were made by Vichet, while the steel cases were made by Georges Croisier (later known as Genevor, which in turn evolved into F.P. Journe’s Les Boîtiers de Genève). The steel cases have a little more angle in the lug profile, and feel a little more substantial, but are still a little dinky by modern standards, explaining their modest profile on the wrist.

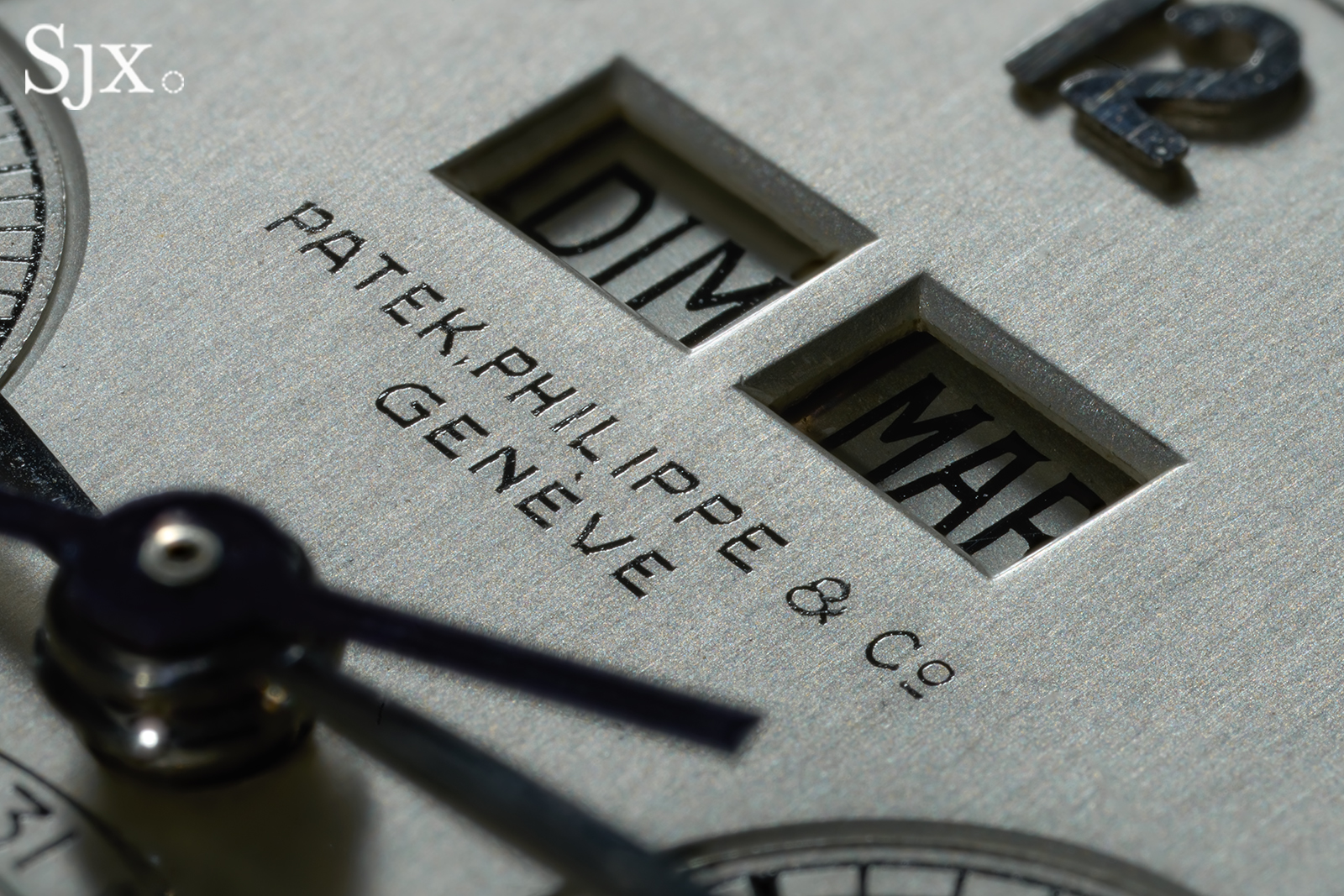

However, Georges Croisier was only responsible the first three of the ref. 1518s in steel, which are numbered sequentially on the cases, “508’473-1”, “508’474-2”, and “508’475-3”, with the serial numbers followed by a single, sequential digit, presumably indicating the order of each case within the batch.

The example going under the hammer at Phillips is “508’473-1” – the “first” one of sorts. Notably, the “first” and “second” examples were both sold at the same retailer in Hungary, Joseph Lang, in 1944. And the “third” example, sold little a later in 1946, is currently on sale at Monaco Legend via private sale.

The inside case back of the ref. 1518 at Phillips marked “1” after the case number, indicating it was “first” in the series. Image – Phillips

Entirely different is the fourth known example that has yet another case type, a little chunkier and made by Wenger. This specimen also differs in terms of numbering, as it bears the case number “633’556-1”, indicating this was the first and only one of the Wenger batch.

This “fourth” example is also visually distinguished by its blued steel hands and more subtly, a slightly different dial.

The “fourth” ref. 1518 in steel with its distinct case made by Wenger and blued steel hands. Image – Patek Philippe Steel Watches by John Goldberger

The unique case profile of the Wenger steel case. Image – Patek Philippe Steel Watches by John Goldberger

Two of the four ref. 1518s in steel are on the market at the moment. Although that might seem like they are often transacted, the four examples have not changed hands much over the past decades.

One example has been owned by well-known Italian collector Sandro Fratini for decades; his collection has been well documented in the large-format book My Time. For a similar lengthy period of time, the “fourth” watch with the blued steel hands has been the property of a gentleman in northern Italy who has an extraordinary but low-key collection of vintage Patek Philippe.

The “third” example now on sale at Monaco Legend was sold by Davide Parmegiani, cofounder of Monaco Legend, some two decades ago, and has only changed hands twice since then, remaining in the same country. And the final example is this one at Phillips, which is being sold by the gentleman who bought it in 2016.

The “second” ref. 1518 in steel, numbered “508’474-2”. Image – Patek Philippe Steel Watches by John Goldberger

The “third” ref. 1518 in steel, numbered “508’475-3”. Image – Patek Philippe Steel Watches by John Goldberger

Details inside and out

All four examples of the steel ref. 1518 contain the same movement found in the gold versions (which was also the same calibre found in the successor ref. 2499): the cal. 13-130 Q.

It was a Valjoux 23 chronograph calibre with a perpetual calendar module added by Victorin Piguet, one of the few firms still building traditional complications by the middle of the 20th century. The cal. 13-130 Q was decorated to an unusually high standard for a wristwatch of the time. Both the base movement and calendar module represent the peak of Vallee de Joux of watchmaking of the period.

The movement inside the “first” steel ref. 1518 at Phillips is surprisingly clean for a watch of this age. Watches from this era tend to show wear on the movement components due to past servicing by less-than-artful watchmakers, but this movement looks good. The steel levers and screw heads have a pleasing finish, and black polished parts like the escape wheel cap and swan’s neck regulator still look black polished.

The movement of the 1518. Image – Phillips

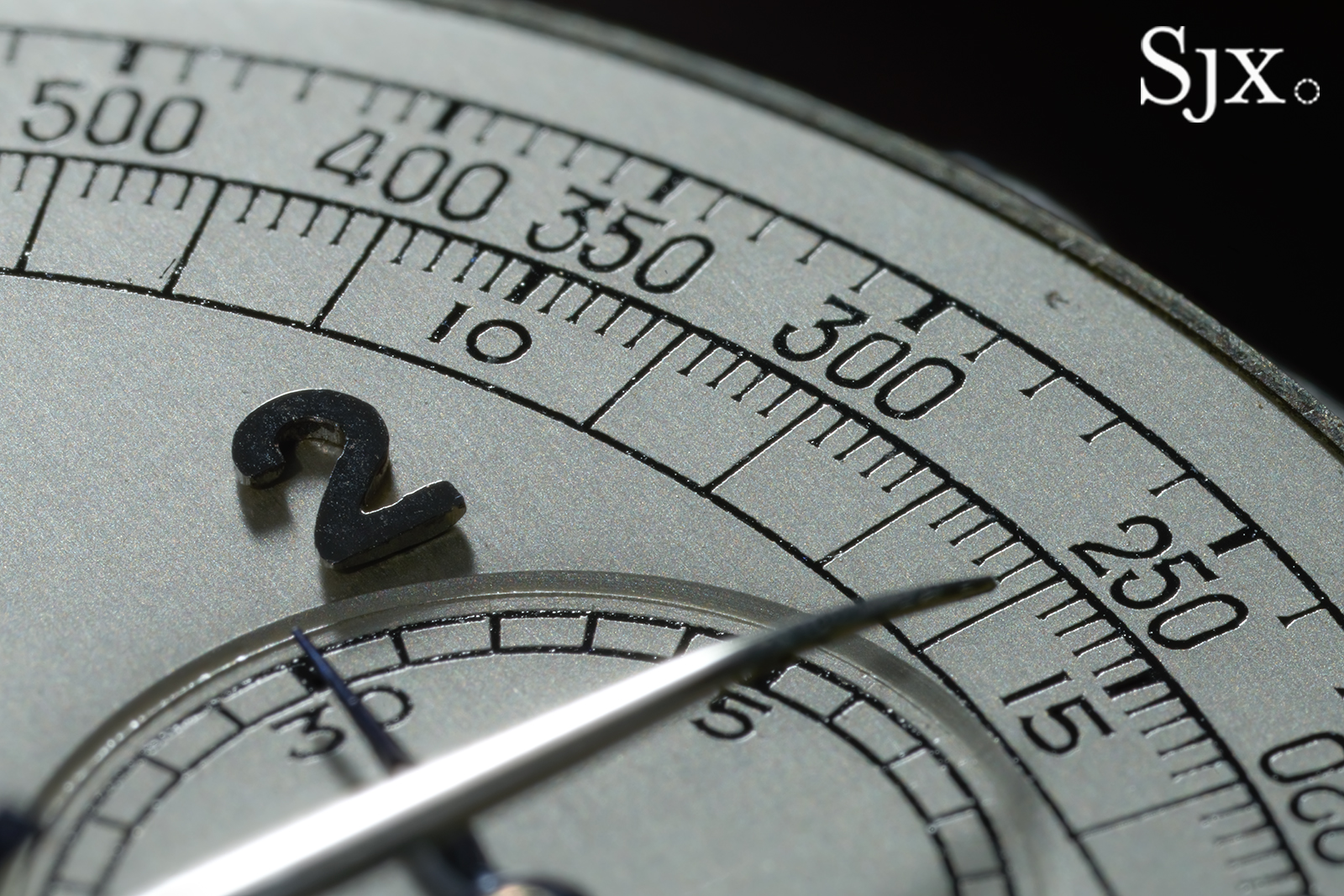

As is almost always the case with vintage watches, more important than the movement is the dial.

Fortunately, the dial stands up to scrutiny. The dial was probably cleaned in the past (as most of the other examples of the steel 1518 were), but retains everything that matters.

Crucially, the champleve enamel markings on the dial reveal the characteristic appearance of the technique, which relies on engraved recessed filled with enamel followed by firing, creating indelible markings on the dial.

The logo under 12 o’clock is a little fainter than the other dial markings, perhaps as a consequence of pasting cleaning. However, it’s important to note the other three identical examples of the steel ref. 1518, namely the “second” and “third” examples, also reveal fainter logos. That may imply the logo was fainter to begin with when the watches first left the Patek Philippe manufacture in the 1940s, then accentuated by cleaning in the intervening years.

Also, the chamfered edges of the window frames and registers remain clean and fairly sharp, another detail that can be lost with excessive cleaning or restoration.

It’s also worth admiring the hands that are particularly well executed with their domed profiles that were almost certainly hand finished. The form is significantly more pleasing than flat, somewhat pedestrian hands on today’s Patek Philippe perpetual calendar chronograph.

The same artisanal quality also can be seen on the gold and blue enamel moon phase disc, which once again stands in contrast to the muted equivalent on the modern-day model.

Once a value proposition

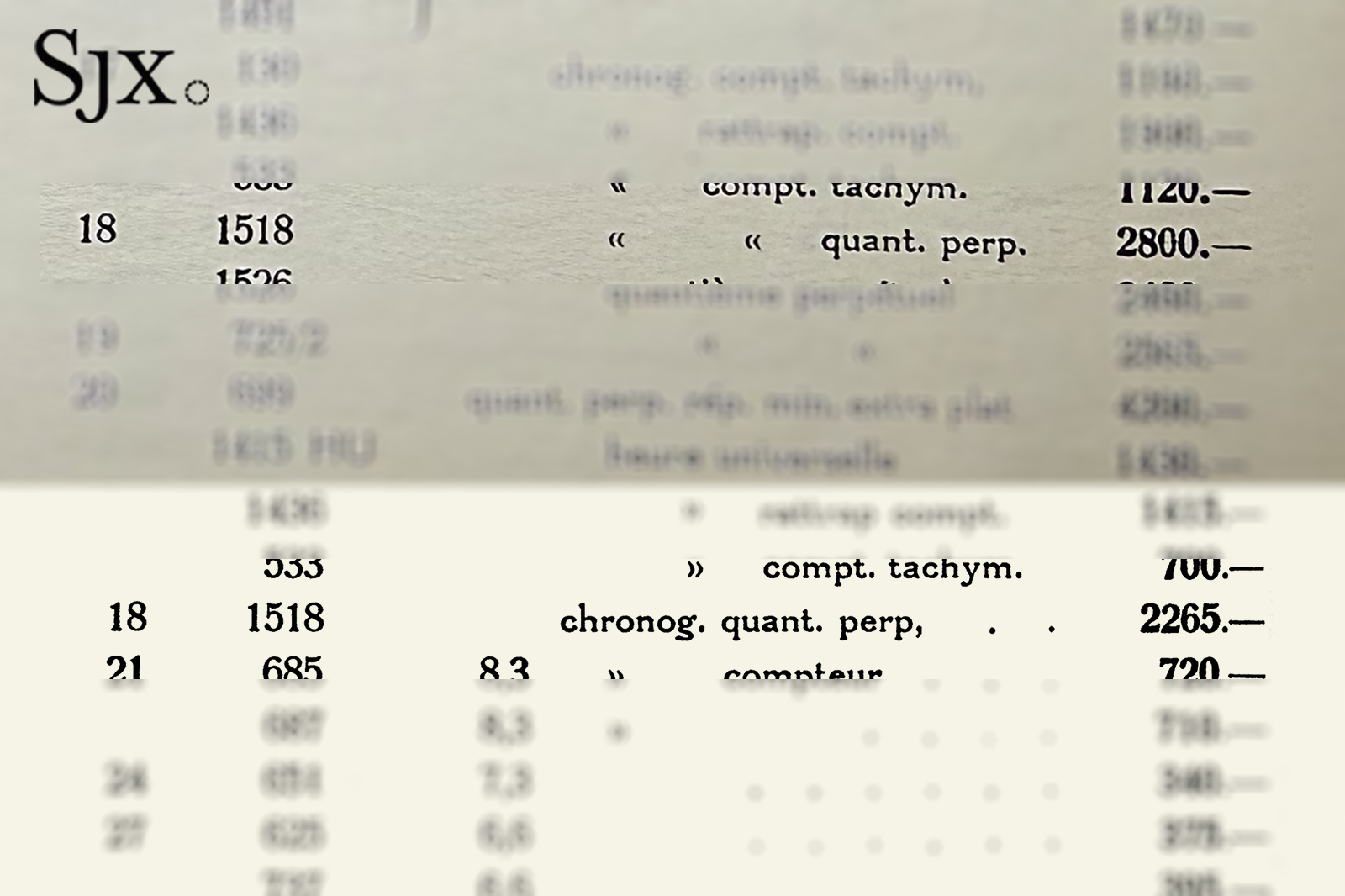

A steel ref. 1518 cost CHF535 less than its gold counterpart in 1944. The 20% difference in price arguably made the steel ref. 1518 something of a value-buy back in the day.

Today this steel ref. 1518 has an estimate “in excess of CHF8 million” – or about ten times the value of a good ref. 1518 in yellow gold.

A 1944 Patek Philippe catalogue with the prices of the ref. 1518 in gold (above), and in steel. Image – Patek Philippe Steel Watches by John Goldberger

In 2016, when this watch sold for nearly US$11 million, vintage watches were all the rage – essentially what independent watchmaking is today – and complicated Patek Philippe in steel even hotter.

Things are different now. There is the steel ref. 1518 at Monaco Legend, priced at over US$20 million. Then there is the weak US dollar, some economic uncertainty, geopolitical challenges – the list goes on.

Yet this steel ref. 1518 is a steel ref. 1518, and that might just be enough to nudge this past its previous record price.

The Patek Philippe ref. 1518 in stainless steel will be sold during Watches: Decade One (2015–2025) auction on November 8, 2025 in Geneva.

Back to top.