Insight: The Modern Performance Chronograph Movement

New takes on classical concepts.

High-end chronograph movements of today tend to have in common a vertical clutch and column wheel. Such “performance” chronographs are typically also automatic, and practically every high-end watchmaker, from Audemars Piguet to Vacheron Constantin, has its own take on the modern “performance” chronograph. The chronograph movement as we know it today is actually a fairly recent invention.

Despite being common in today’s chronograph constructions, the vertical coupling, or at least its concept, is decades-old. The Pierce cal. 130/134 launched in the 1930s is regarded as the first commercially available wristwatch with a vertical clutch. There are examples of even older stopwatches that relied on crude forms of the vertical clutch, but most were either prototypes or small-batch production.

But the large-scale use of the vertical clutch only started in the late 1960s, when Seiko debuted the cal. 6139. Launched in 1969, the Seiko cal. 6139 was a vertical clutch movement produced on an industrial scale.

Not only was it among the first-ever automatic chronographs, but the cal. 6139 also was objectively the most advanced amongst them. Compared to the modular construction of the Breitling-Heuer Chronomatic Caliber 11 and the fairly classical architecture of the Zenith El Primero, the Seiko cal. 6139 was endowed with a vertical clutch and a novel construction all around. It was, however, an industrial, no-frills movement at heart.

The one that started it all – the cal. 1185

Arguably the quintessential modern automatic chronograph movement, of the type we find in high-end watches today, is the Frédéric Piguet cal. 1185 introduced in 1988. It featured an innovative construction that combined the reliable vertical clutch with the distinguished column wheel, all contained in a notably compact package. Furthermore, it could be easily customised to carry a rattrapante module or flyback function.

At just 5.55 mm in height, the cal. 1185 was for a long time the thinnest automatic chronograph movement on the market.

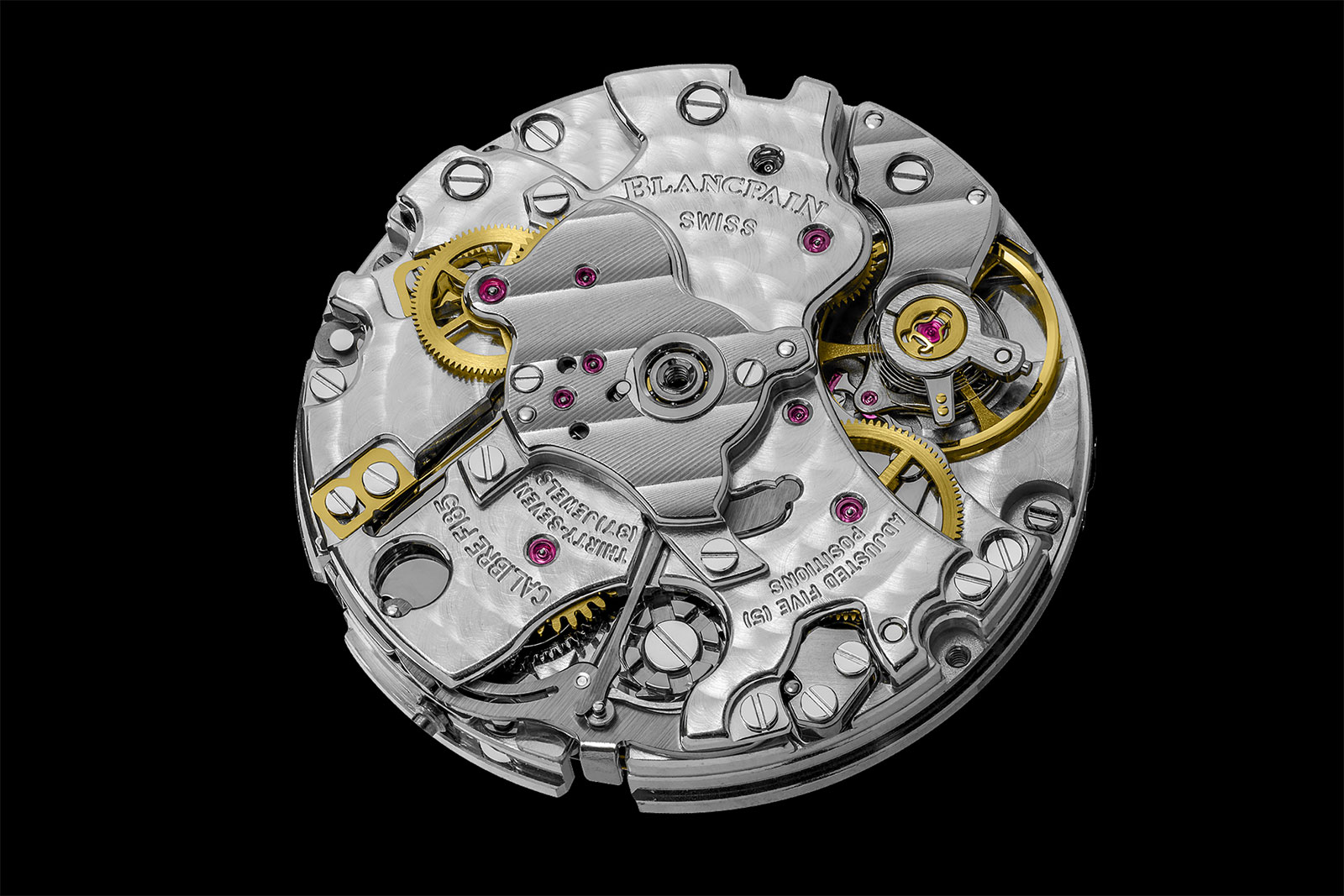

This made the cal. 1185 a high-grade calibre, especially compared with the workhorse of the era, the Valjoux 7750, which was considered an impressively reliable, albeit thick, movement without much refinement. As a result, the cal. 1185 quickly became the default choice of chronograph movement for many high-end watch brands, most notably Frédéric Piguet’s sister brand Blancpain, but also Audemars Piguet, Breguet, Vacheron Constantin, and Cartier amongst others.

Interestingly, Edmond Capt, who is widely credited as the father of the Valjoux 7750, was in fact the technical director of Frédéric Piguet during the years of the cal. 1185’s development, but it is not known how active he was in its creation.

The manual-wind version of the cal. 1185 was known as the cal. 1180

The cal. 1185 exhibits some interesting construction choices, from the three-quarter-like upper plate that conceals almost most of the chronograph works, to the one-piece triple reset hammer. The only visible part of the chronograph system is the small column wheel, positioned far from the movement’s centre.

The chronograph seconds, minutes, and hours wheels are all collinear and are reset to zero by a long, three-headed hammer. The vertical clutch is of fairly ordinary construction, with the central seconds mobile driving the other indications. All the levers and springs are flat and intentionally spread out wide rather than layered, a key factor behind the movement’s thinness.

The cal. 1185 without its rotor

Over time many brands shifted towards in-house chronograph movements, but the influence of the cal. 1185 remains visible in those very in-house movements from the likes of Blancpain, naturally, but also Jaeger-LeCoultre, Omega, and Cartier.

The in-house Blancpain F385 is, in a wider sense, an evolution of the cal. 1185.

Equally, the Jaeger-LeCoultre cal. 751 is basically a heavily reworked cal. 1185 construction. Amongst other things, it was endowed with a second mainspring barrel and an updated automatic winding system, but it still has recognisable elements of the cal. 1185 layout, including the column wheel position.

The familiar column wheel position in the Jaeger-LeCoultre cal. 751

The “performance chronograph”

The implementation of the vertical clutch, along with other advancements in component manufacturing and materials science, has given birth to what is best described as a “performance chronograph”, essentially a sophisticated movement designed to maximise the chronograph function.

The trend more or less started with the introduction of the first in-house Rolex chronograph movement in 2000, the cal. 4130 that made its debut in the Daytona ref. 116520.

The all-new Daytona then boasted a robust, sophisticated new movement that was marketed as reliable and precise, one that paralleled the status of the Daytona as a watch synonymous with the highest echelons of motorsport.

The chronograph works in the Rolex cal. 4130

Other brands soon followed suit with their own “performance chronograph” movements, sometimes thanks to former Rolex engineers joining other companies. These included the very reliable Breitling B01 of 2009 and the advanced Omega cal. 9300 (now 9900) in 2011.

Even high horology brands started employing the vertical clutch in their sports offerings, for example Patek Philippe with its CH 28-520 that debuted with the ref. 5960P in 2006, or the more recent Audemars Piguet cal. 4400.

The Audemars Piguet cal. 4400 with one clutch pincer is visible next to the balance bridge

Further refinements

One of the advantages of the vertical clutch is the reduction of “stutter”, a wavering or jumping central seconds when starting the chronograph. However, the vertical clutch mobile itself might be subject to a lack of continuous tension from the gear train, which could induce stutter.

The venerable cal. 1185, for example, has the centrally-mounted vertical clutch driven by the going train via an intermediate pinion. Since the clutch assembly is under no tension, there are two points of inevitable gear play.

One point sits between the going train’s seconds wheel and the intermediate pinion, while the second point of play is between the intermediate pinion and the vertical clutch. This means that such a construction can suffer from angular gear backlash, leading to phantom hand stutter.

This issue was solved in newer performance chronographs by using gears manufactured via the LIGA lithography technique that allows the gears to incorporate teeth with shallow elastic toothing. The sprung teeth expand slightly against the solid teeth of a classic gear, ensuring the meshing is as tight as possible. This doesn’t allow for any backlash, virtually eliminating play or stutter.

A LIGA gear in the Rolex cal. 4130

The newer iterations of the Rolex cal. 4130 feature two such specialised LIGA gears. One is the large wheel with sprung teeth that links the vertical clutch to the central chronograph seconds hand.

And the second is a LIGA pinion with elastic toothing that sits co-axial with the going train seconds wheel, and is geared to the lower portion of the vertical clutch. The going train tensions the vertical clutch and the central seconds wheel is tensioned relative to the clutch.

Rolex also notes the elastic toothing in these gears acts as a torque damper to protect the wheel’s integrity. The brand argues in its European patent EP2112567A1 that the sudden acceleration impressed on the seconds wheel when the chronograph is reset can harm a classic toothing. Thus the elastic teeth that can absorb and disperse some of the sudden change in torque. This is an interesting insight, which is only rarely discussed.

The self-tensioning meshing between a classic and a LIGA gear

The Breitling B01 also features such a LIGA part, namely an intermediate pinion. The B01 architecture is similar to the cal. 1185 in the sense that the centrally-mounted vertical clutch is geared to the going train via an intermediate pinion. It is that intermediate pinion that features elastic toothing, economically eliminating both points of gear backlash at once. The pinion is tensioned relative to both the gear train and the vertical clutch, meaning motion is transmitted between the latter two virtually without play.

Back to top.