As we approach the leap day of February 29, the unofficial day of commemoration for perpetual calendar owners, it’s worth considering the technical advances in perpetual calendar movements of the past 20 years.

The perpetual calendar is, and has always been, a staple of haute horlogerie. But for most of its history, the technology remained largely stagnant. It wasn’t until the beginning of the modern era, in the 1980s when Swiss watchmaking was regrouping after the Quartz Crisis, that a new generation of watchmakers revisited this complication in earnest. In particular, they sought to address fundamental weaknesses in the way traditional perpetual calendar designs switch from one date to the next.

The quintessential perpetual calendar layout, here in the first serially-produced perpetual calendar wristwatch with a leap year indicator, the Audemars Piguet ref. 5516, which was produced in the late 1950s

One of the more recent – and most notable – efforts at reimagining the complication came from Stephen McDonnell, who developed the MB&F Legacy Machine Perpetual. According to Mr McDonnell, the traditional approach to the perpetual calendar was a flawed premise.

“For decades in the Swiss watch industry, and even until the present day, it has been accepted and expected that [perpetual calendar] watches would often be damaged by owners while trying to correct them,” explains Mr McDonnell, “This was seen simply as an unavoidable factor of [perpetual calendar] ownership. These pieces would then return again and again to the after sales service for repair, and so the cycle would continue.”

The MB&F LM Perpetual

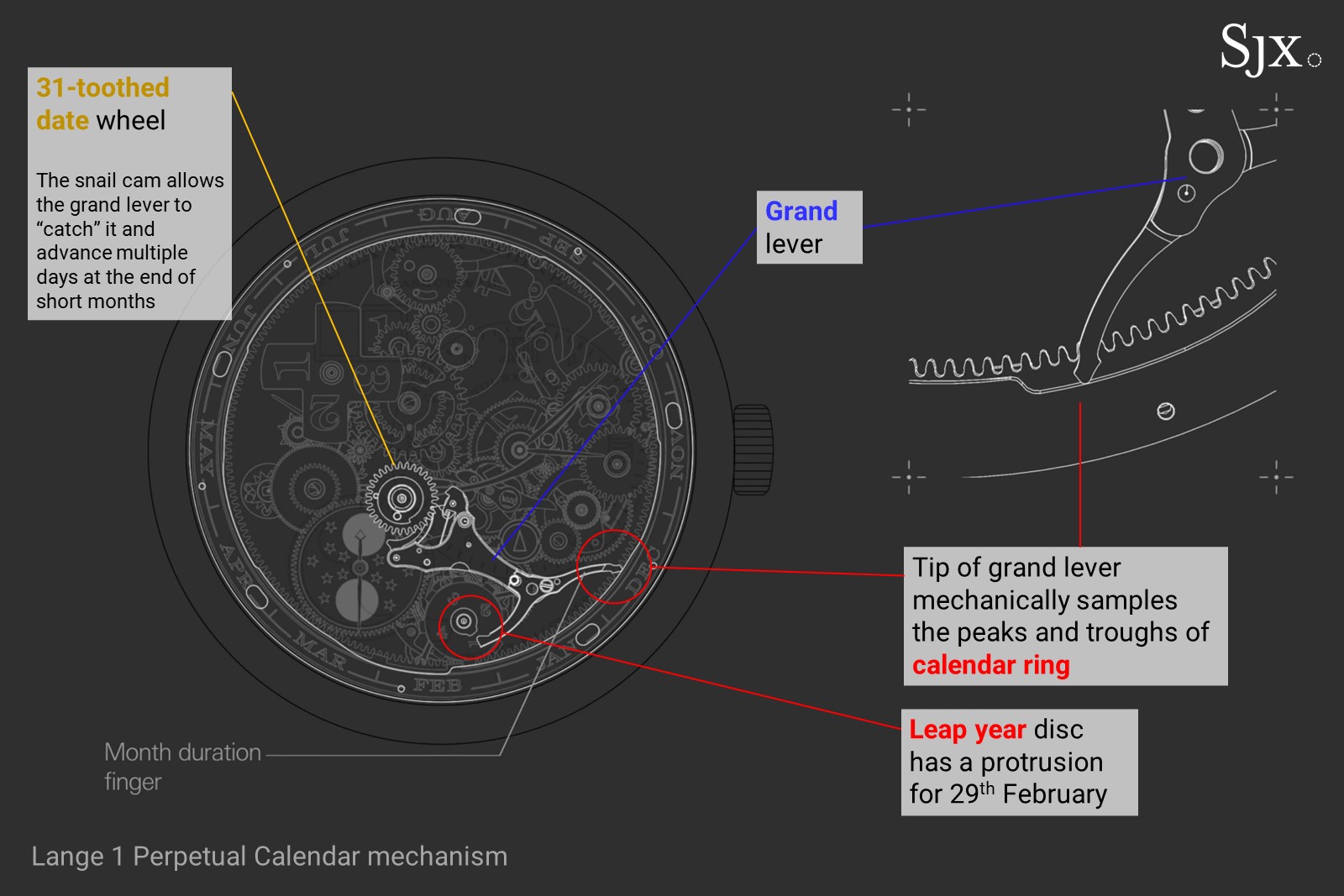

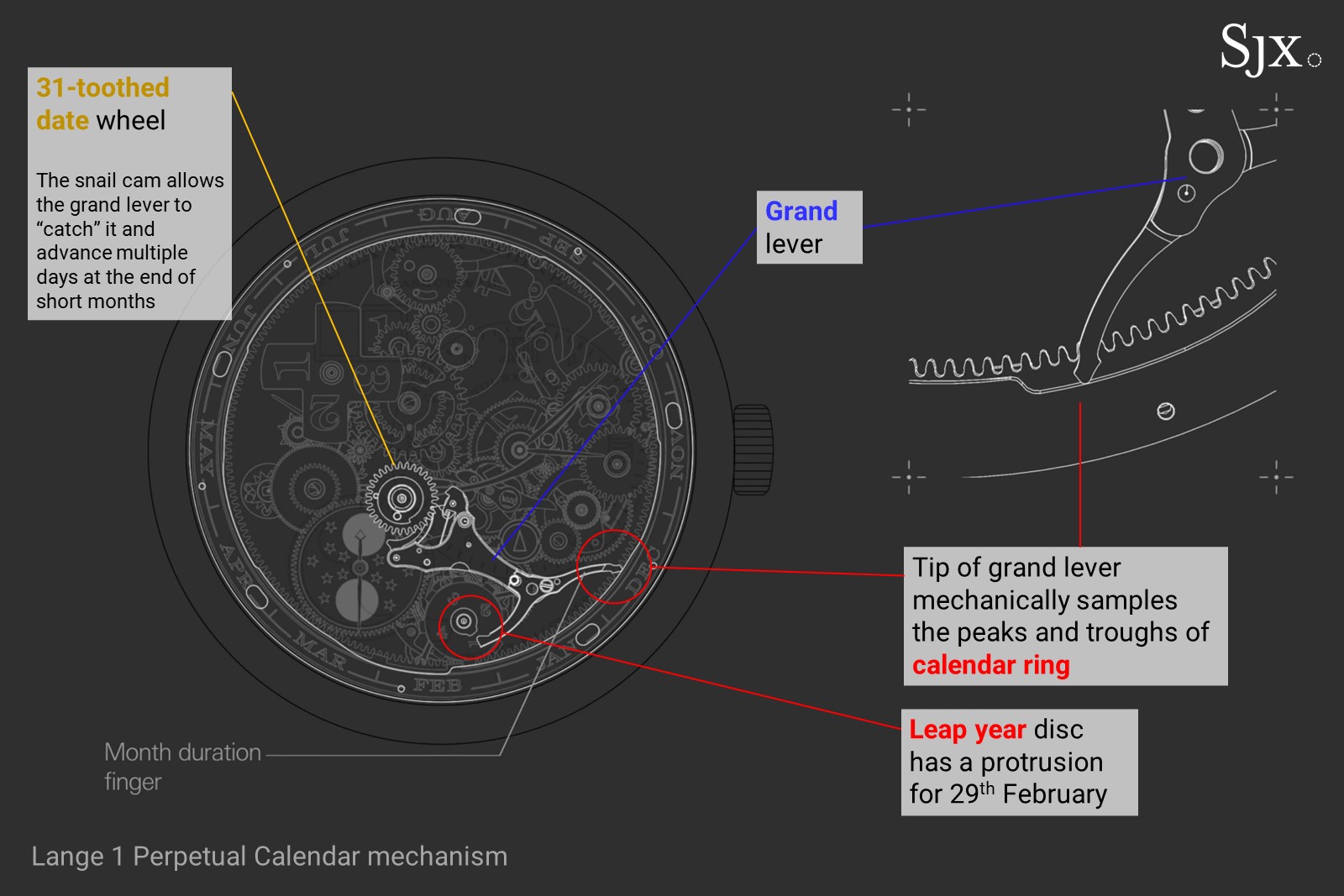

The root of this problem lies with the so-called “grand lever”, a reference to the key component in the traditional construction of the complication. In this construction, a multi-pronged lever steps each date indicator forward every day. According to Mr McDonnell, the grand lever “has very poor horizontal stability, and if everything is not absolutely optimised, or even if one of the correctors is forced a little, its extremities can rise up and skip over things.”

Fortunately, the past two decades have witnessed numerous innovations in the way perpetual calendars function, both on a fundamental level and in terms of the user interface, to move ever closer to the conceptual ideal of the perpetual calendar.

The conceptual ideal

Imagine a theoretically perfect perpetual calendar. Design aside, it would require the following attributes:

- Intuitive and unambiguous display of information

- Simple date setting, without the need for special tools

- No “dead zone” that will damage the movement when adjusting the watch

Let’s define each of these criteria more fully.

Information display

An intuitive and unambiguous display of the date starts with a proper understanding of the order of priority for each indicator. In other words, knowing which calendar indication is most important and relying on the dial design to put it at the top of the visual hierarchy.

According to Dr Ludwig Oechslin, the polymath renowned for the innovative perpetual calendar watches that he developed for Ulysse Nardin, the ideal information hierarchy for a calendar watch is 1) the time, 2) the date, 3) the weekday, and finally 4) the month. For a perpetual calendar, the leap year indicator would naturally be fifth.

The Greubel Forsey Quantième Perpétuel à Équation demonstrates a solid grasp of the priority of information, with the date emphasised relative to the month, date, and leap year indicators.

Setting without tools

In a perfect perpetual calendar, the process of setting the date would also be simple and intuitive, and would not require special tools. While this may seem like an obvious criterion, most perpetual calendar watches are set via pushers recessed in the case, meaning they can only be actuated using a stylus.

This inconvenient manner of setting arises, in part, because traditional grand lever based designs cannot be adjusted backwards. If the date is accidentally set to a future date, the user must either stop the watch and wait for the future date to arrive, or cycle the date indicators forwards until the correct date is again shown.

Since the former is impractical, most brands have settled on using quick-set pushers to adjust each indicator forward individually, in theory reducing the amount of effort needed to cycle forward to the correct date, day, and month.

The grand lever highlighted in the Lange 1 Perpetual Calendar.

Pushers can make quick work of adjusting the date, but they create new problems. For one thing, they create more points of failure in the case where water can enter. Case in point, the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Perpetual Calendar (regardless of case material), which relies on pushers for the calendar indicators, is rated to just 20 m of water resistance, compared to 50 m for its time-only sibling.

Another problem is that pushers, or more specifically the need for a stylus, increases the chance of human error – namely, losing the stylus!

The pushers are particularly obvious on the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Perpetual Calendar in black ceramic

The “dead zone”

On the topic of human error, the ideal perpetual calendar would have no dead zone, meaning it would be safe from damage even if adjusted during the hours when the calendar is changing. Unfortunately, grand lever-based constructions often have a long switchover period between 8:00 PM and 2:00 AM, during which time adjusting the date or moving the hands backward will damage the movement.

This means the user must remember their watch’s dead zone and, critically, have some means of distinguishing between AM and PM. For many brands, insuring against this risk of user error means cluttering the dial with yet another indicator to show AM/PM.

The Patek Philippe ref. 5236P features an AM/PM indicator at eight o’clock to help the user avoid the dead zone.

Towards the ideal

The perpetual calendar has a long history, having been invented in London by Thomas Mudge in 1762, around the same time that he invented the lever escapement. The perpetual calendar eventually became a fixture of complicated pocket watches, but it wasn’t until 1925, when Patek Philippe squeezed a pendant watch-sized perpetual calendar movement into a wristwatch case, that the first perpetual calendar wristwatch was born. A few years later, in 1929, Breguet created what is thought to be the first perpetual calendar movement designed specifically for use in a wristwatch.

The Patek Philippe perpetual calendar wristwatch from 1925

These were one-off, experimental products, both technically and commercially, and it took a few decades before the perpetual calendar evolved into its current form, thanks primarily to developments by Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet:

- 1941: Patek Philippe ref. 1526 – first series-produced perpetual calendar wristwatch

- 1955: Audemars Piguet ref. 5516 – first perpetual calendar with leap-year indicator

- 1962: Patek Philippe ref. 3448 – first automatic perpetual calendar

But these early perpetual calendars utilized a grand lever for switching, and therefore suffered from the tedious setting ritual already described. They were also manually wound, due to the fact that automatic winding systems had yet to achieve mainstream adoption. This increased the regularity of the setting ritual.

A ref. 1526 in pink gold

In this context, the 1962 introduction of the Patek Philippe ref. 3448 was a major breakthrough, as it was the first automatic perpetual calendar. This did nothing to make the calendar easier to adjust, but it did help ensure the watch stayed wound, cutting down on how frequently updates needed to be made, improving the user experience.

However, once perpetual calendars became automatic, almost exactly 200 years after the complication was invented, development entered a stagnant period that lasted more than two decades. Despite the introduction of ever-thinner perpetual calendar modules, the fundamentals remained unchanged until 1985.

A rare variant of the ref. 3448 in platinum

The transitional period

The 1980s were a chaotic time in Switzerland. The Quartz Crisis had wiped out much of the Swiss watch industry, and the surviving brands were fighting to make mechanical watches relevant again.

Against this backdrop, Kurt Klaus, the long-serving technical director at IWC, developed an innovative perpetual calendar module designed to fit the Valjoux 7750 chronograph. Whereas all previous perpetual calendar designs were adjusted via pushers in the case, Mr Klaus managed to design a module that enabled all adjustments to be made via the winding crown.

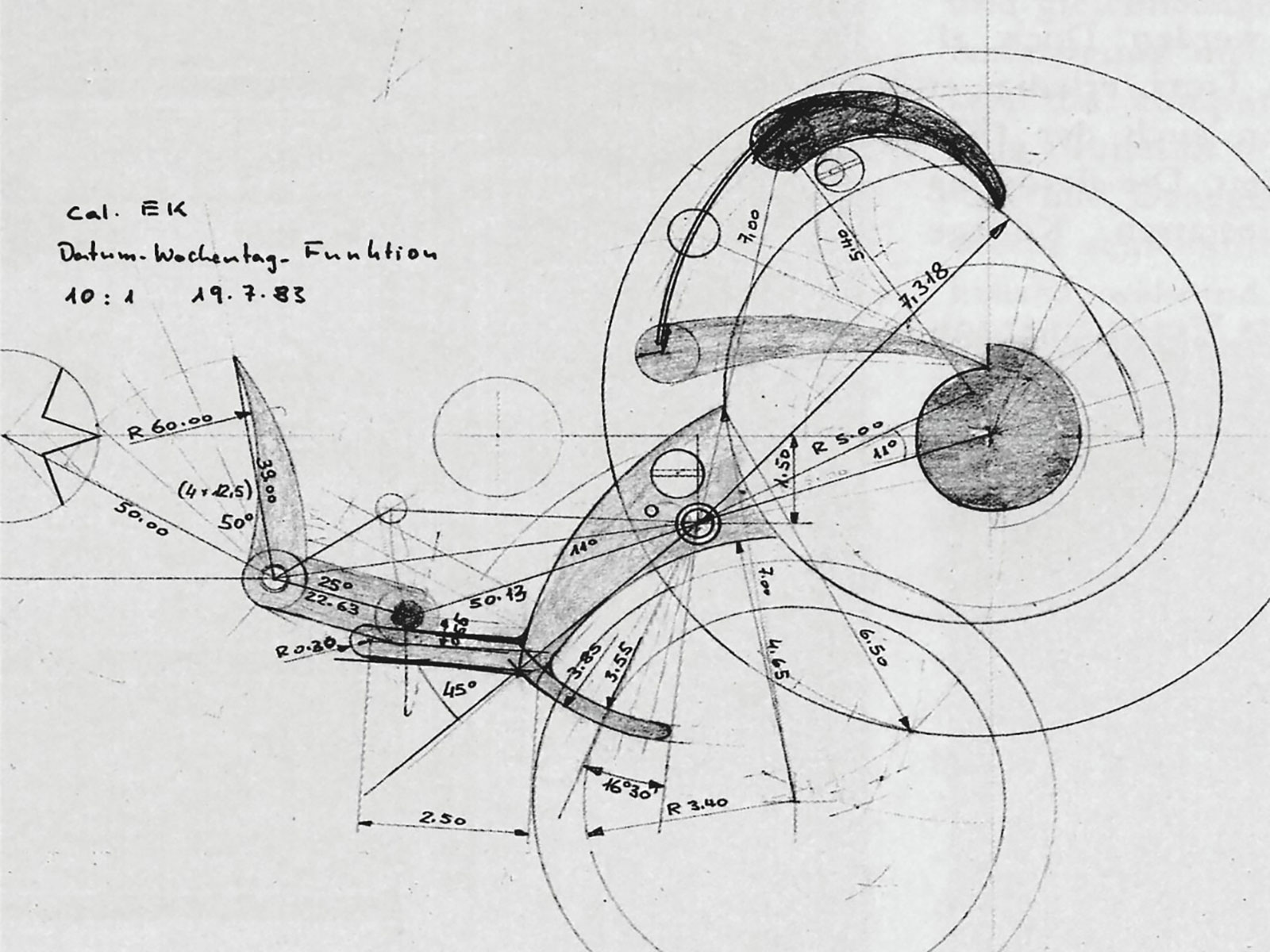

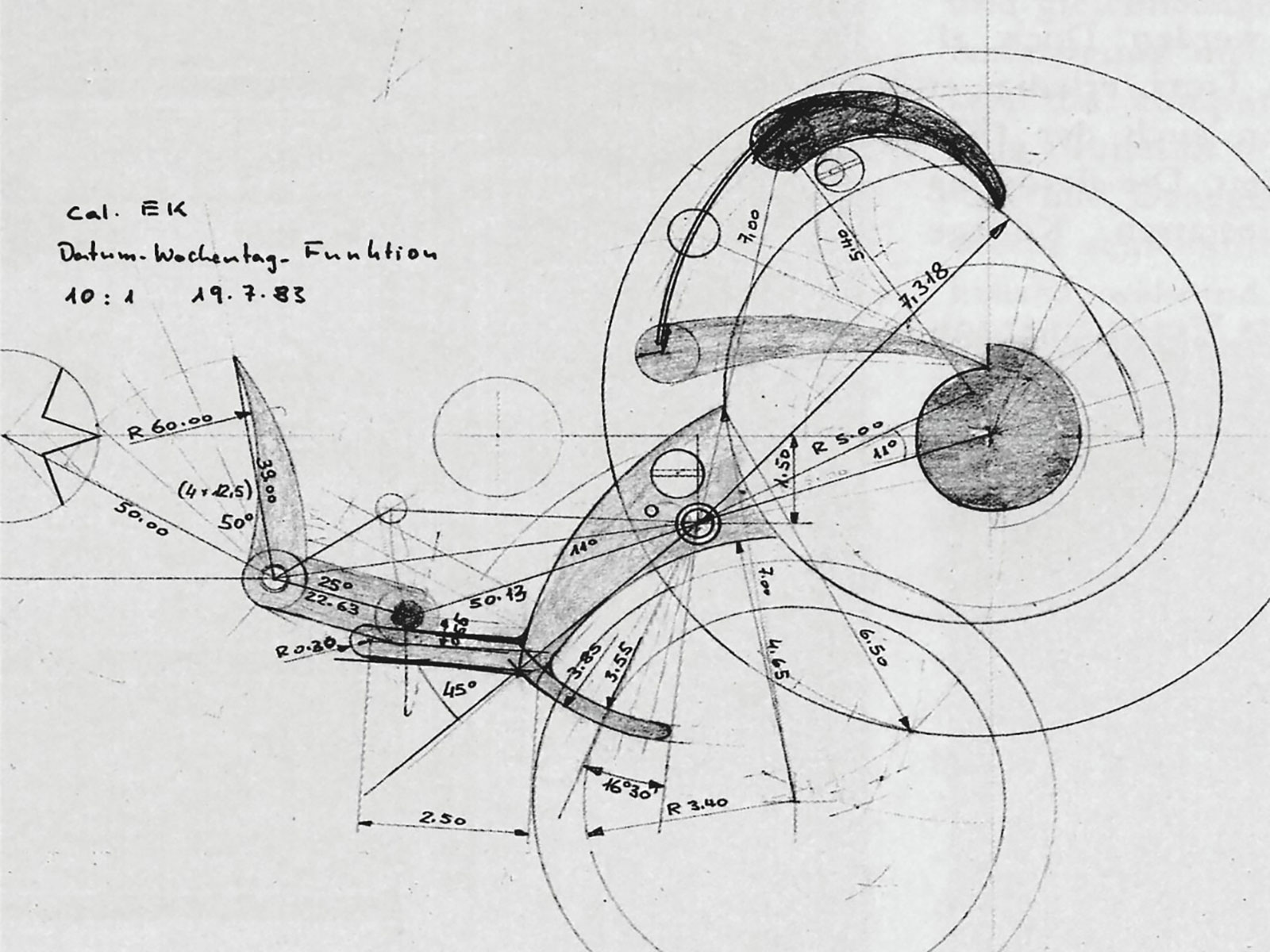

Mr Klaus’ 1983 sketch for “Cal. EK”, short for ‘ewiger kalender’, German for “perpetual calendar”. Photo – IWC

This system offered several benefits. For one thing, getting rid of the case pushers improved the look, and also the water resistance, of the case. Second, the user could dispense with a stylus and make any needed adjustments on-the-go. This design also required fewer components than traditional perpetual calendar platforms and was therefore more cost-effective to produce. Finally, the consolidation of all adjustments into the crown resulted in a more intuitive user interface.

This platform debuted in 1985 in the Da Vinci, and was justly viewed as a major breakthrough. This perpetual calendar module is still in use by IWC today, and was also subsequently been adopted by Jaeger-LeCoultre, as both brands shared common ownership (then, as now).

The original Da Vinci perpetual calendar from 1985, complete with four-digit year indicator (a world first). Image – IWC

Despite the long-term success of the Da Vinci module, a few problems remained and a new one was created. At its heart, the Da Vinci was built around the grand lever, so the date indications could not be adjusted backward, and the dead zone remained. Furthermore, the Da Vinci module utilised a fully programmed calendar, with all indications synchronised.

The synchronisation of the calendar functions is what enabled Mr Klaus to reduce the complexity of the calendar module, but it prevented the indicator-level cycling that was possible with earlier platforms. This means that if the date is inadvertently set to a future date, the user must either let the watch stop until that future date arrives, or, if that date is sufficiently far into the future, send the watch in for a service to reverse the mistake.

Things changed in a big way in 1996 when Ulysse Nardin introduced the Perpetual Ludwig, which included a groundbreaking perpetual calendar module developed by Dr. Ludwig Oechslin. The Perpetual Ludwig (which was reissued in 2019) was the first perpetual calendar that could be adjusted backward.

The 2019 reissue of the Perpetual Ludwig, which was largely faithful to the 1996 original.

This seemingly minor development eliminated an entire category of problems that had plagued the perpetual calendar since its earliest development, namely the need to go all the way around a full leap year cycle in order to set the date backward. By replacing the grand lever with a simplified system of stacked gears, Dr. Oechslin was also able to eliminate the dead zone for the first time.

Despite its significant advances, which ushered in a new era for the perpetual calendar, the date indications of the Perpetual Ludwig were not instantly switching, meaning it takes some time for all of the date indicators to changeover at midnight. In addition, the date indicators are distributed somewhat haphazardly across the dial, reducing the legibility and design possibilities.

All things considered, these are minor limitations, but they left the door open for other brands to make their own mark on the history of the perpetual calendar. The first brand to strike was a startup that would later develop a reputation for upending many of the traditional norms of the watch industry.

The H. Moser & Cie. Perpetual 1

In the preface to the third edition of Watchmaking, George Daniels notes, “Care in the design of the wristwatch is necessary if the dial is not to resemble a gas-meter – as the cluttered faces of so many modern watches do.” This might as well have been the design brief for the H. Moser & Cie. Perpetual 1 released in 2006.

The H. Moser & Cie Perpetual 1 remains the ultimate ‘sleeper’ perpetual calendar. Photo – Phillips

When Moser launched the Perpetual 1, it was a fledgling startup trying to establish its reputation. With the goal of making a bold statement, the brand tapped Andreas Strehler, an independent watchmaker known for his technical ingenuity, to design the movement and build the prototype.

The resulting watch was ruthless in its priority of information, eliminating the weekday indicator entirely and moving the leap year indicator to the case back (since it’s typically referenced only when setting the setting). This left the date, displayed in a novel single-pane big date format at three o’clock, and a small central hand indicating the current month, conveniently read against the 12 hour indices.

This radical approach to design mirrored the technical innovations within. For one thing, the HMC 341 was the first perpetual calendar movement that can be adjusted forward and backward and features an instant date change, with both the date and month indicators snapping forward promptly at Midnight.

This functionality, which Moser calls the Flash Calendar, also provides an ancillary benefit: a large date in a single-pane date window. This is done with a clever two-layer date disk; the upper disk for the first 15 days of the month, and the lower disk for the remaining 16 days.

The Flash Calendar features a two-tiered date wheel. Image – Moser

This arrangement does two things. First, it provides space for larger numerals, making it a true big date. Second, it means the date can jump directly from February 28 to March 1 without cycling through 29, 30, and 31.

The Perpetual 1 also challenged what had become an unquestioned expectation for perpetual calendars: automatic winding. Since the introduction of the Patek Philippe ref. 3448 in 1962, automatic winding was considered vital for reducing the burden of owning and using a perpetual calendar.

But Moser designed the Perpetual 1 to be as easy to set as a watch with a simple date function, a category in which automatic winding is not considered vital. Perhaps to convince any would-be naysayers, Moser endowed the movement with a lengthy seven day power reserve, complete with a dial-side power reserve indicator.

Incredibly, the caliber HMC 341 eliminated the dead zone as well, meaning the time and date could be adjusted in either direction at any time. But with exceptional capability often comes exceptional complexity. The Perpetual 1 was an ambitious watch in 2006, especially for what was then a startup. Like many ambitious projects, delivery of the watch was delayed several years and early examples had teething problems.

The HMC 808 is one of the latest variants of the original HMC 341.

Fortunately, these problems were resolved and Moser continues to produce an evolution of this movement, the HMC 800, 17 years later. During this update, numerous components were redesigned to improve reliability and ease of manufacture. When an early movement comes in for service today, it gets upgraded to the latest revision of the HMC 341, which is conceptually identical to the newer HMC 800. In my view, this is a sensible service policy that supports the desirability of the early production models.

The minimalist Moser Streamliner Perpetual Calendar

The pusher for the quick-set year sits at the 10 o’clock position

With such an emphasis on crown-based adjustment, eagle-eyed observers may have noticed a case pusher located at nine o’clock and wonder what that’s for. It is an auxiliary quick-set year pusher, enabling full-year jumps to make it easier to set the date if the watch has not been worn for a period of years.

F.P. Journe Quantième Perpétuel

Another significant development came in 2013 with the launch of the F.P. Journe Quantième Perpétuel and its cal. 1300.3. While the Moser Perpetual 1 brought instant switching to the modern perpetual calendar, F.P. Journe sought to make its own mark on the category.

Like the Moser Perpetual 1, the date on the F.P. Journe Quantième Perpétuel can be adjusted via the crown and features an instantly jumping large date display. But the similarity ends there, as FP Journe, true to form, differs in several interesting ways.

The F.P. Journe Quantième Perpétuel was the first perpetual calendar to feature instantly jumping displays for the date, day, and month, all of which are arranged intuitively. Photo – FP Journe

First, all three primary calendar indications, including the weekday, are instantly switching. Second, these indicators are displayed in windows in the center of the dial. This configuration enables the user to read the day, month, and date in an intuitive way.

Third, the watch features a quick-set month, by means of a switch located underneath one of the lugs. This enables the user to cycle through all 48 months of the leap-year cycle in under a minute. In my view, this is an improvement compared to the quick-set year pusher on the Moser, since it’s likely to be useful more often and dispenses with any form of special tool.

Furthermore, FP Journe developed a novel approach to the calendar function that eliminates the dead zone. Finally, the Quantième Perpétuel is built on the mature Octa automatic movement, which offers a five day power reserve to further minimise the need to adjust the date.

MB&F Legacy Machine Perpetual

By 2013, the key problems of the perpetual calendar had been fully addressed, and the likelihood of further innovation seemed remote. But MB&F proved otherwise in 2015 with the launch of the Legacy Machine Perpetual (LM Perpetual), designed by Stephen McDonnell.

While Moser and F.P. Journe focused on consolidating adjustment by means of the crown, Mr McDonnell went in the opposite direction, distributing adjustment pushers for each indicator around the case. “From a practical point of view, I want an elegant and intuitive mechanism which, at the single touch of a pusher, allows me to adjust for a whole month or a whole year,” explains Mr McDonnell, “I also want to have full, independent control over all corrections for days, months and years.”

This meant coming up with his own solutions to the challenges of building a reliable perpetual calendar. The result was a mechanical processor that bases every month on 28 days, adding days when necessary. And as Mr McDonnell points out, the LM Perpetual enables the user to quick-set the year without any special tools; an industry first.

No stylus needed; the pushers for adjusting the date can be actuated with a finger.

“[A crown-operated calendar] necessitates the use of many gears, all on top of each other,” continues Mr McDonnell, “From an aesthetic point of view, it is very difficult to make this look good, which is why the mechanisms of such systems are usually kept hidden under the dial.”

In contrast, McDonnell’s mechanical processor helps the LM Perpetual stand out aesthetically, being the only watch from among the new breed of perpetual calendars to reveal its calendar works prominently under the dial.

It’s doubly impressive to achieve this level of technical functionality with a layout that offers so much micro-architectural interest. Mr McDonnell says that it was very important “to be able to showcase beautiful components in an exciting, dramatic and elegant way.”

The calendar mechanism is on full display, giving the LM Perpetual a distinctive aesthetic

Furthermore, there is no dead zone. This was one of the fundamental challenges that Mr McDonnell sought to overcome when he began imagining his own take on the complication. His design prevents damage by disengaging the pushers during certain hours.

These safety mechanisms seem to work. MB&F reports that after delivering about 500 LM Perpetuals across 12 different versions, the few watches that have come in for service have done so for the typical generic issues that would be encountered by any ordinary watch, suggesting they have not seen any user-damaged calendar mechanisms.

Like the Moser, the LM Perpetual eschews automatic winding. Having eliminated the pain points that tend to accompany setting a perpetual calendar, it’s no longer essential to ensure the watch never stops.

Perpetuals today

Despite the progress made over the past 20 years to idiot-proof the perpetual calendar, most of those currently on the market are grand lever designs that require a stylus to engage external pushers to adjust the calendar displays. Even those that don’t need a stylus often have a dead zone, requiring the user to take multiple steps, sometimes over several hours, to make certain adjustments (especially when traveling east across the International Dateline).

Perhaps in recognition of how convoluted instructions like these can be, Moser recently introduced the amusing “Tutorial” edition of its flagship Endeavour Perpetual Calendar, which features a dial with annotations around each function and indicator, reminding the user that operation is “foolproof.”

The Endeavour Perpetual Calendar Tutorial edition. Photo – Moser

Of course, functionality is just one dimension of what makes a great watch. One likely explanation for the durable demand for traditional grand lever-based perpetual calendars is the aesthetic. With myriad sub-dials and indicators, these designs tend to offer a certain antiquarian charm that is arguably missing from the ruthlessly efficient designs of H. Moser & Cie. and F.P. Journe.

Collectors often lament the lack of innovation in the mechanical watch industry, a complaint that has driven the increasingly widespread usage of space age materials like silicon. But innovation takes many forms, and sometimes it hides in plain sight. In my view, real innovation creates tangible improvements in the user experience of wearing and operating the watch, and the brands pursuing this type of progress are moving the industry forward in a meaningful way.

Back to top.