The Intrigue & Significance of the Patek Philippe Owned by the Last Emperor of China

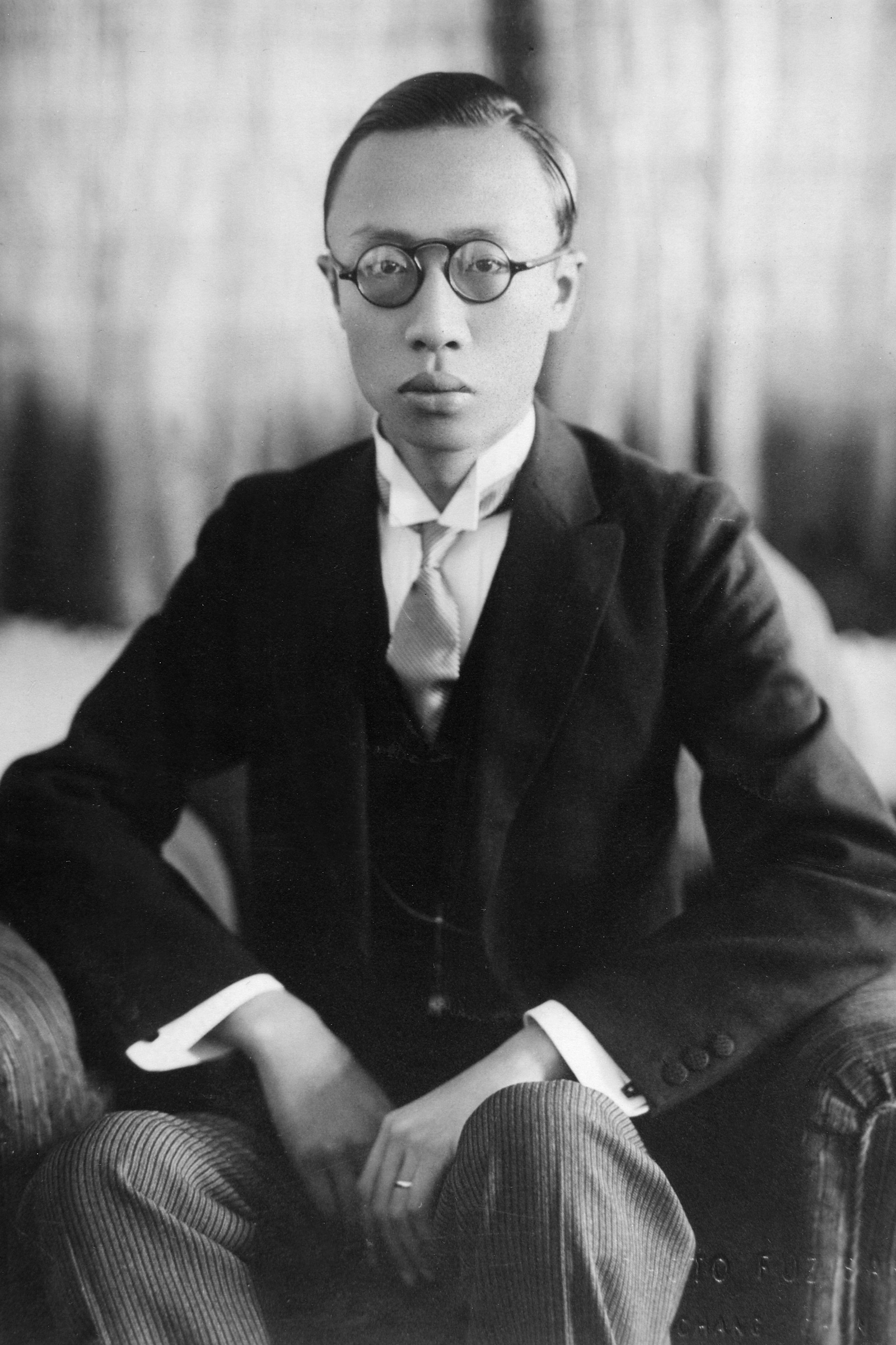

Puyi's ref. 96.

A historically important Patek Philippe Calatrava ref. 96 with full calendar and moon phase will soon be offered at Phillips, but the news isn’t so much about the watch itself but the story behind it.

While extraordinarily rare in itself, the ref. 96 quantieme lune is exceptional for its provenance: its original owner was Aisin-Gioro Puyi, the last emperor of China and heir to a 4,000-year old imperial throne. As the final ruler of the Qing Dynasty, Puyi was arguably a hapless individual overcome by circumstances and overtaken by history – a life dramatised in the Bernardo Bertolucci’s film The Last Emperor – leaving him with a mixed reputation and legacy.

The ref. 96, however, makes clear his appreciation of mechanical timepieces. Yet this long-lost imperial watch is extremely flawed on its face. But the heavily-aged dial, seemingly severely damaged, also echoes the tale of Puyi’s brief reign, a turbulent time when an empire met its end and a feudal dynasty was transformed into a modern nation.

Image – PaddleWaves

An Emperor’s timekeeper

Ascending the throne at age two in 1908, Puyi was destined for a life of absolute power. But shortly after, the child Emperor witnessed the collapse of Imperial China and his family’s four century-old dynasty in the wake of the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 that gave birth to the Republic of China.

In 1932, perhaps unwitting or naive, he became the titular ruler of Manchukuo, the puppet state of Manchuria that was controlled by Japan. Despite being a figurehead with no real power, Puyi’s dozen-year tenure as Emperor of Manchukuo ensured his historical legacy would forever be controversial.

Puyi

This ref. 96 was delivered in October 1937, meaning Puyi received it during his time as ruler of Manchukuo. The watch was certainly amongst the most expensive watches in the world at the time, making it an unsurprising timepiece for a man who no doubt still harboured imperial ambitions. The watch also reflects the fact that Puyi was the only Chinese emperor who was a watch collector in the modern sense; several of his other watches and clocks are on display in the Palace Museum in Shenyang.

Puyi’s fate after his spell as ruler of Manchukuo was ignominious for a man who once ruled China. After Japan’s defeat in 1945 and the fall of Manchukuo, Puyi was imprisoned in the Soviet Union, before eventually being repatriated back to Communist China.

The former emperor had no children and much of what he owned was dissipated as he went from one prison to another before spending his later life as a free man living in modest circumstance.

By the time he died in 1967, the ref. 96 and his other fine possessions must have been a distant memory. Like most of what he owned, the ref. 96 was lost for decades.

Lost and found

I first encountered this watch in 2019 when it was offered for sale by a dealer in Europe, having been in the same family since Puyi left a Soviet prison decades ago. The family were the descendants of a Soviet official who served as Puyi’s translator during his years in captivity.

When he left Soviet custody, Puyi gave the watch to the official, whether willingly or under duress is unknown. Alongside the watch, the official also received several of Puyi’s belongings, including a fan bearing a hand-written inscription by Puyi, books, and watercolour paintings by Puyi and his brother. (The watch has been consigned to Phillips by the individual who subsequently purchased the watch and its accompanying items, and not by the family of the Soviet official.)

The ref. 96 along with Puyi’s fan. Image – Phillips

It’s almost a century since Puyi acquired the ref. 96, so the watch bears obvious signs of wear. Fortunately, the case appears to be in unrestored condition – “unpolished” as some enthusiasts would say – and its edges remain sharp.

Then the obvious question: what happened to the dial? At first glance it appears to be extreme aging, but Puyi’s diary reveals the full story.

Image – PaddleWaves

A curious emperor

Puyi writes that when he received the watch, he was curious as to whether the dial was pure gold. He summoned an attendant and ordered him to scrape off the varnish and silver plating to reveal the base material of the dial. After the attendant had worked through the lower half of the dial, Puyi realised to his disappointment that the dial was merely brass, so he asked the attendant to stop.

While such damage to a dial would ordinarily discourage a buyer, the amusing story behind it adds a tangible and personal connection to the former emperor, a tangible connection that is missing from most “celebrity” watches, even ones with well-documented provenance.

Image – PaddleWaves

The long road to historical importance

Despite its damaged appearance, the dial has a peculiar appeal. It is instantly recognisable and radiates an enigmatic charm in person.

More broadly, this watch is the ultimate example of a historically important timepiece. The provenance adds tremendous mystique to a very rare watch. Even Paul Newman’s “Paul Newman”, John Lennon’s Patek Philippe ref. 2499, and even the Omega Speedmaster that went missing after the 1969 Moon landing cannot compare.

That’s simple due to the documented personal connection to Puyi. The watch is a vivid, physical expression of a curious man who was only emperor briefly yet never learnt to live like an ordinary person. The link between Puyi’s personality and the watch makes it incredibly special.

Image – Phillips

And the watch is important for wider cultural reasons. The fact that the former owner was Puyi instantly sets it apart from other watches owned or worn by notable historical personalities, who are mostly Western.

For centuries, practically all of the world’s best known watchmakers have come from a handful of mostly Western countries, with the most obvious being Switzerland, but also Germany, Britain, the United States.

Unsurprisingly, all of the most valuable timepieces to date have associations with the Western culture. For instance, the four-minute tourbillon pocket watch made by the A.-L. Breguet for King George III and the Rolex “Paul Newman” Daytona worn by Paul Newman himself. That will soon change with Puyi’s ref. 96 going under the hammer.

A very different 96

Putting aside its historical significance, this ref. 96 is important in itself. The watch is undoubtedly important in the history of Patek Philippe and arguably important in the wider history of watchmaking.

To start with, this ref. 96 was the first-ever serially-produced wristwatch with a complication. Prior to this, Patek Philippe already made complicated wristwatches, including perpetual calendars and split-seconds chronographs, but all were unique creations, essentially custom watches for specific individual clients. Eight examples of the ref. 96 calendar are known, with one sharing the exact same configuration as Puyi’s watch.

As for the watch itself, it is unexpectedly diminutive. The case measures about 30 mm, a size that underscores the movement’s mechanical sophistication. With neither computer-aided design nor modern production equipment, the movement is a marvel considering its size and complexity.

Crack open the case back and the impressive, old-school finishing is evident: wide Côtes de Genève on bridges that sport chamfered edges, an elegant finish on all the gears, and a barrel ratchet wheel with wolves teeth. There is no doubt that this was one of the finest examples of watchmaking of its era, a watch fit for an emperor.

Puyi’s ref. 96 will be on display at Phillips’ new office in the West Kowloon Cultural District from March 18-31. It will then go on tour around the world before being offered for sale sometime in the future.

Back to top.