A Family Heirloom and the Legacy of American Watchmaking

A man, his watch, and a vanished industry.

This is the story of a man, my great grandfather Dominik “Dinko” Bakuk Kovacevic, his Waltham pocket watch, and the legacy of the American watch industry.

Though he died before I was born, Dinko is a significant figure in my life because I was given my middle name, Dominic, in his honor. Dinko was born in 1875 in Stari Grad on the island of Hvar on the Dalmation coast of what is now Croatia, but was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As a young man, Dinko joined the short-lived Austro-Hungarian Navy and quickly rose through the ranks to become an officer.

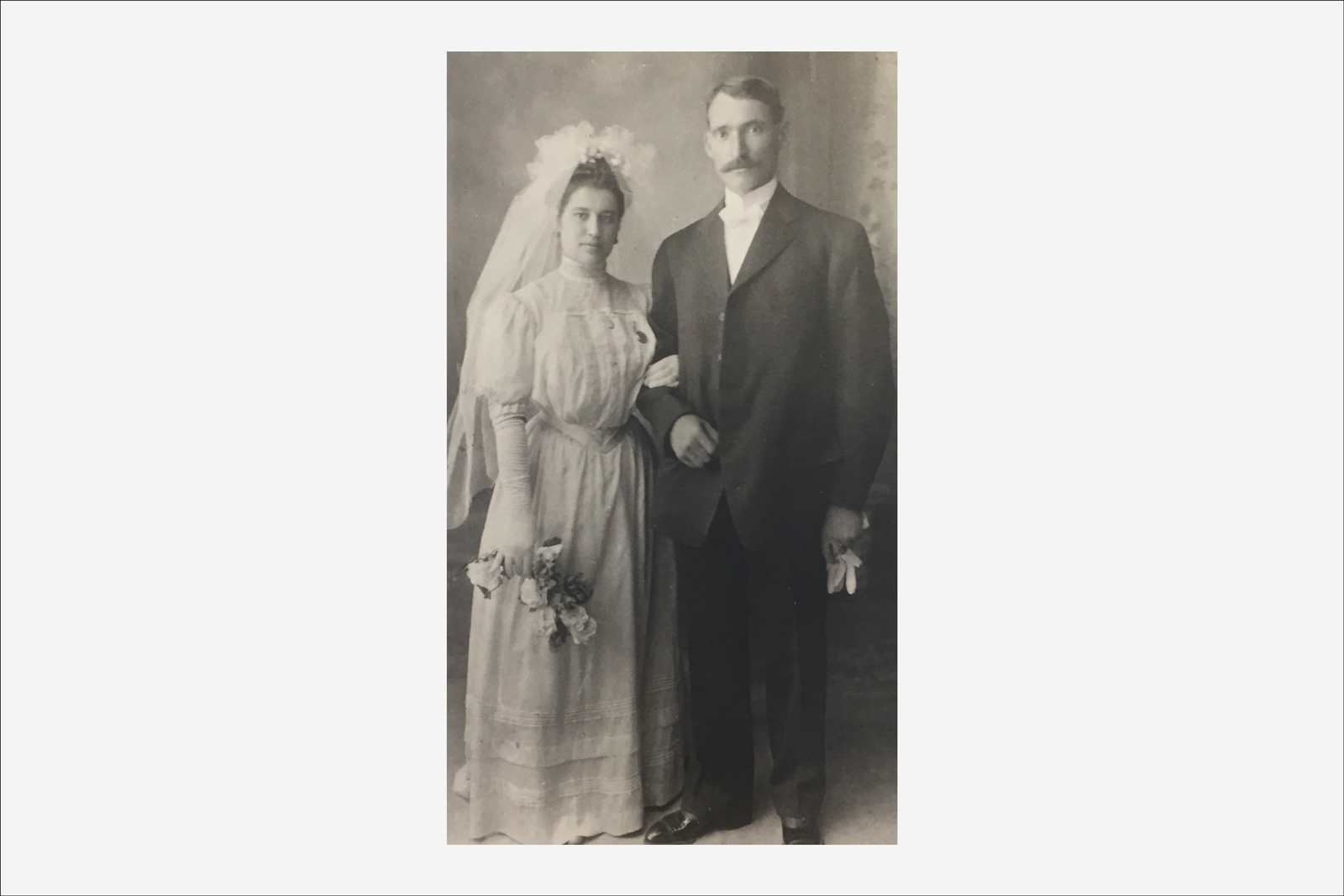

My great grandparents, Dominik and Aloisia Kovacevic, on their wedding day in 1908

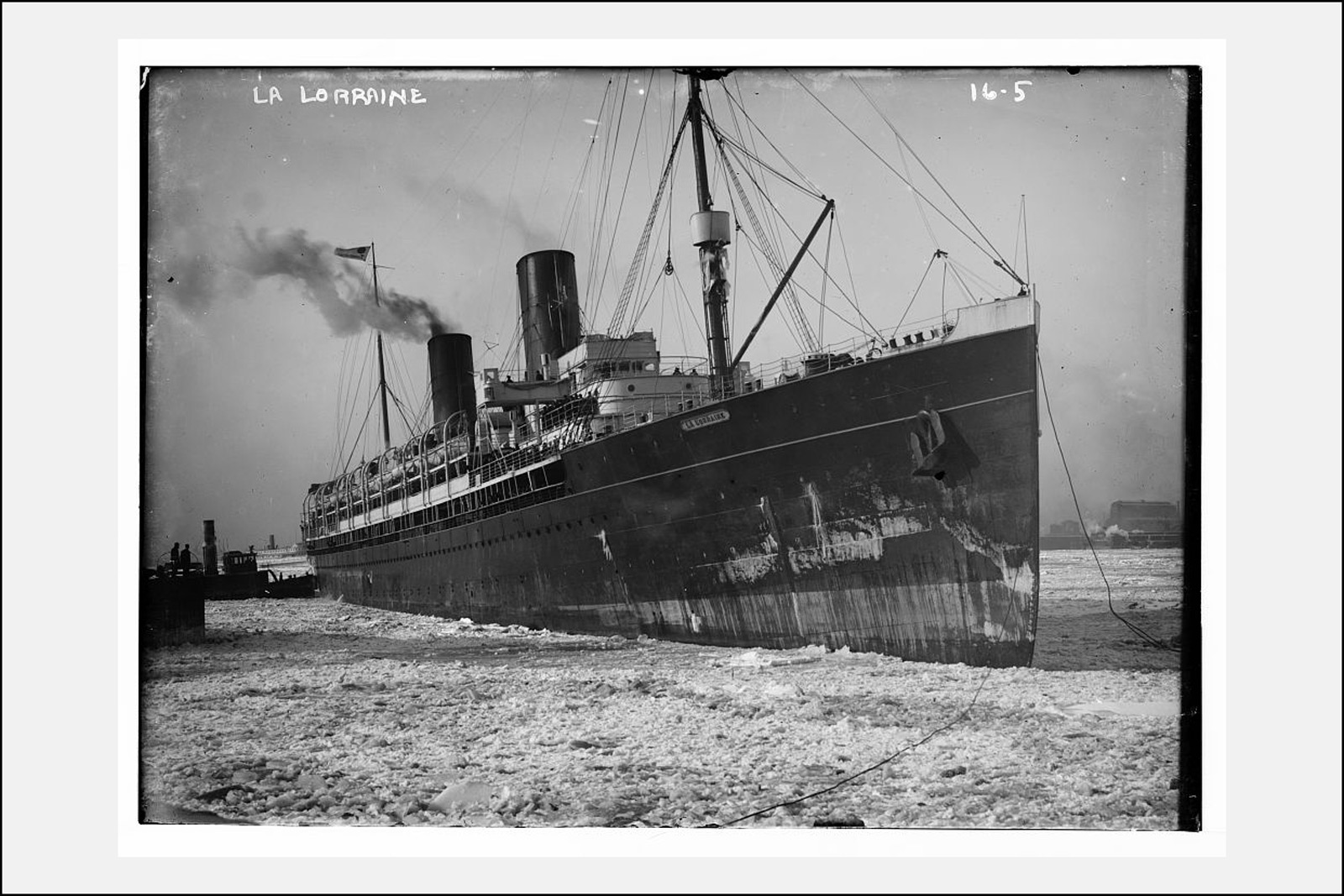

Following his military service, at the age of 27, he set sail from the French port of Le Havre for New York City, aboard the SS La Lorraine. He arrived on Ellis Island in New York Harbor on August 16, 1902. He was joined by his fiancee Aloisia six years later, and they were married a few days after her arrival in the US in 1908.

The SS La Lorraine, the ship that brought Dinko to the United States in 1902. Image – Library of Congress

After his arrival in the US, Dinko moved west, like many entrepreneurial immigrants of his generation. By 1920, he was the proprietor of a grocery store in Tonopah, Nevada, before eventually settling near Berkeley, California where my mother’s family still lives. Dinko passed away in 1953, by which time he was affectionately known within the family as “Grandpa Old Man.”

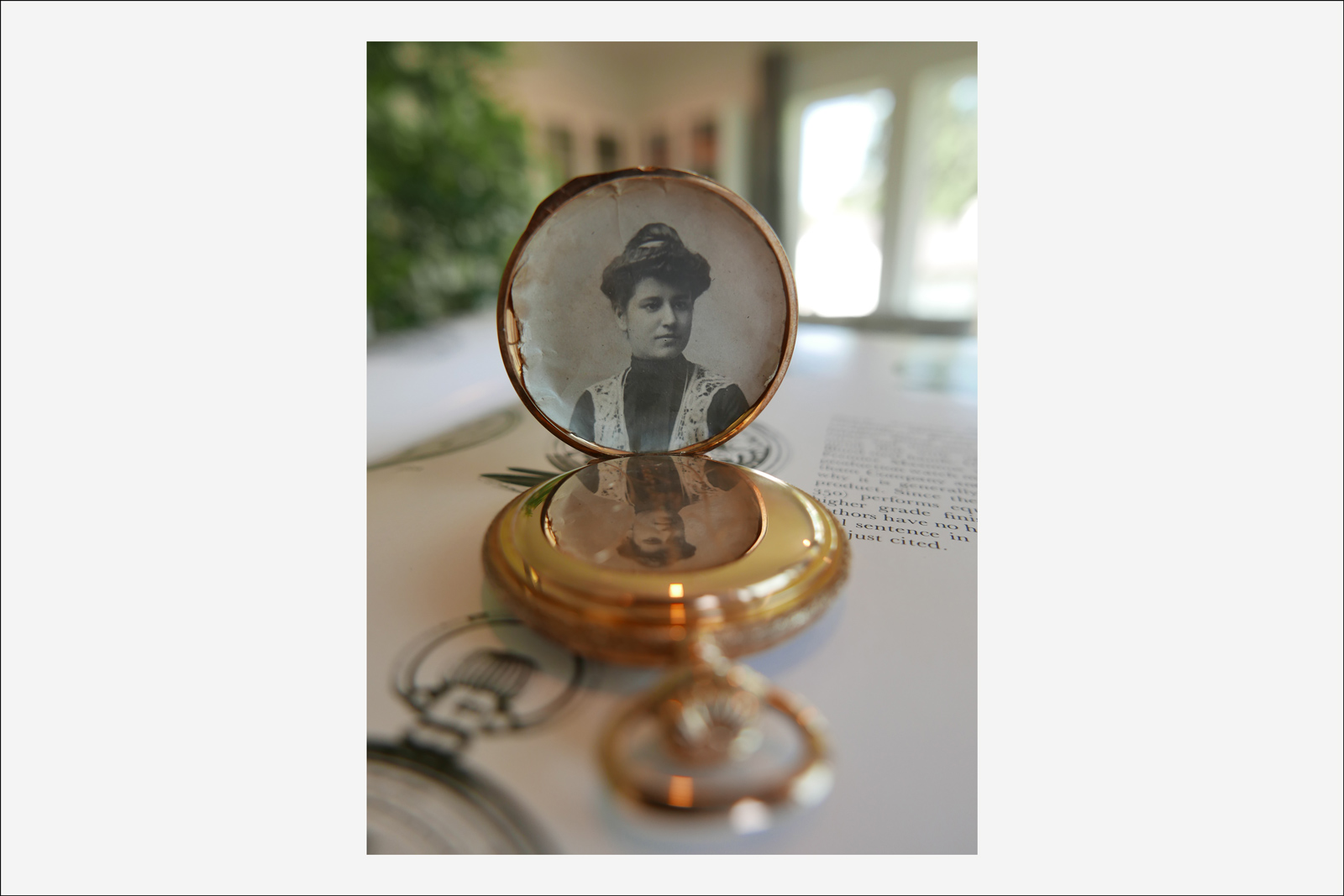

My great grandmother, Aloisia Eisenhart, in a photograph that has been kept in the back cover of the watch for more than 100 years

Dinko’s Waltham Riverside Model 1894

Dinko’s watch is a Waltham Riverside Model 1894, manufactured in 1903. It’s not clear exactly when Dinko bought the watch, but I guess it would have been between 1903 and 1908. The photo of Aloisia was something he kept in the hinged case back during the six years that they were apart.

George Daniels wrote glowingly about the Waltham in the third edition of Watches: “America also produced watches of quality and high performance; notable were the Waltham, Elgin, Illinois, Howard, and Hamilton companies. Although unable to compete with the more flexible Swiss system, their products are rightly prized. No pains or expense were spared to achieve the highest quality and they may take their place in the most select horological company. Outstanding is the highest grade of Waltham, the ‘Riverside Maximus.’”

The watch is housed in a 14k gold, full hunter case adorned with a combination of guilloche and hand engraving. It features a white porcelain dial with extremely fine, blued steel hands.

The case is decorated with both engine turning and hand-engraving

The keyless movement is 39.79 mm in diameter and has a nickel finish. The movement features 19 jewels, five of which are set in gold chatons. According to pocketwatchdatabase.com, a website dedicated to historical American pocket watches, Waltham produced 83,096 of these movements.

The bimetallic, split balance

The movement features a gorgeous blued steel Breguet overcoil hairspring, and a cut bimetallic balance that accounts for fluctuations in temperature. Reserved for Waltham’s finest watches, compensation balances of this type would take about 85 different machining operations to produce.

The balance also features four gold timing screws (one is visible near 12 o’clock in the image above) in addition to the more common poising screws. This indicates that some regulation was accomplished by adjusting the inertia of the balance.

The Starwheel micrometric regulator

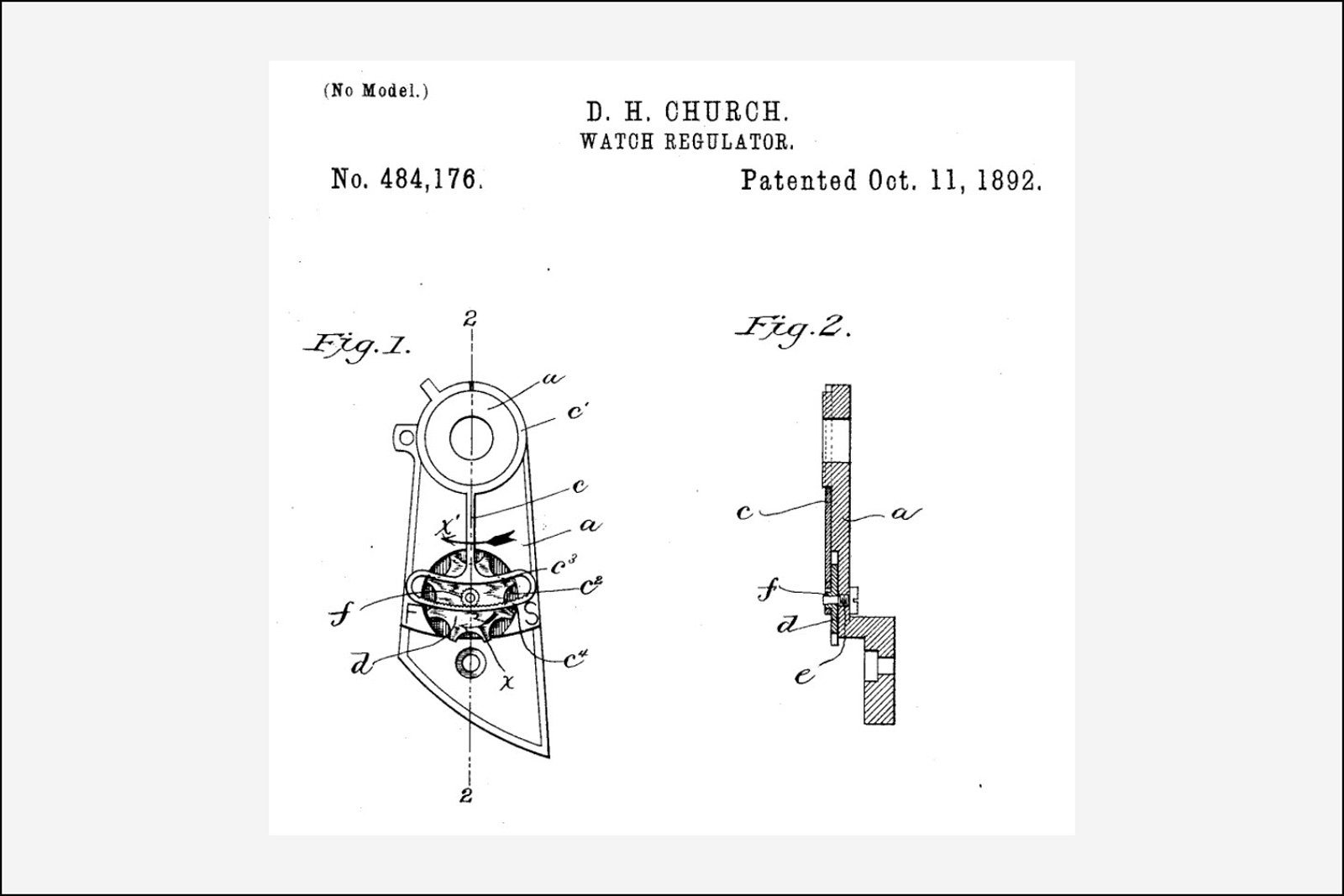

The movement’s most distinctive feature is its Starwheel micrometric regulator, developed by Duane H. Church for Waltham in 1892, for which he was awarded US patent US484176A the same year. The Starwheel regulator was one of dozens of regulator designs patented by the various American watch companies between 1850 and 1900, each designed to be more economical to produce and easier to adjust for low-skilled workers.

Technical drawings of Waltham’s Starwheel micrometric regulator as depicted in the patent filing

The other striking aspect of the movement is the finishing. The plates and bridges are damascened, an elaborate finish that George Daniels noted was “typical of most American high grade watches.”

The damascene finish of the plates and bridges. Note also the vivid color of the blued steel overcoil hairspring

A new threat from the new world

American watches like the Waltham Riverside had a profound impact on the Swiss watchmaking, helping shape the industry into what it is today. If you’ve ever had a watch serviced by the manufacturer or purchased a watch made after 1877, you’ve likely experienced the legacy of the American watch industry. How did this happen?

In the 1870s, the Swiss watch industry was flying high, with a global market share of 80% and climbing, thanks to the stagnation of the English and French watch industries. American watchmaking firms shared just a sliver of this global market – around 5%. But this number, like the size of the domestic market in the United States, was growing rapidly.

In just a few short years, from 1872 to 1876, Swiss exports to the United States declined 74%, from over 18 million francs to less than 5 million francs, according to Harvard historian David Landes writing in Watchmaking: A Case Study in Enterprise and Change.

Waltham’s output alone increased almost ten times between 1872 and 1889, when the factory produced more than 880,000 watches. In contrast, Longines only managed to produce 20,000 watches in 1885, and 130,000 in 1905, despite having one of the largest and most modern factories in Switzerland at the time according to Swiss watch historian Pierre-Yves Donzé.

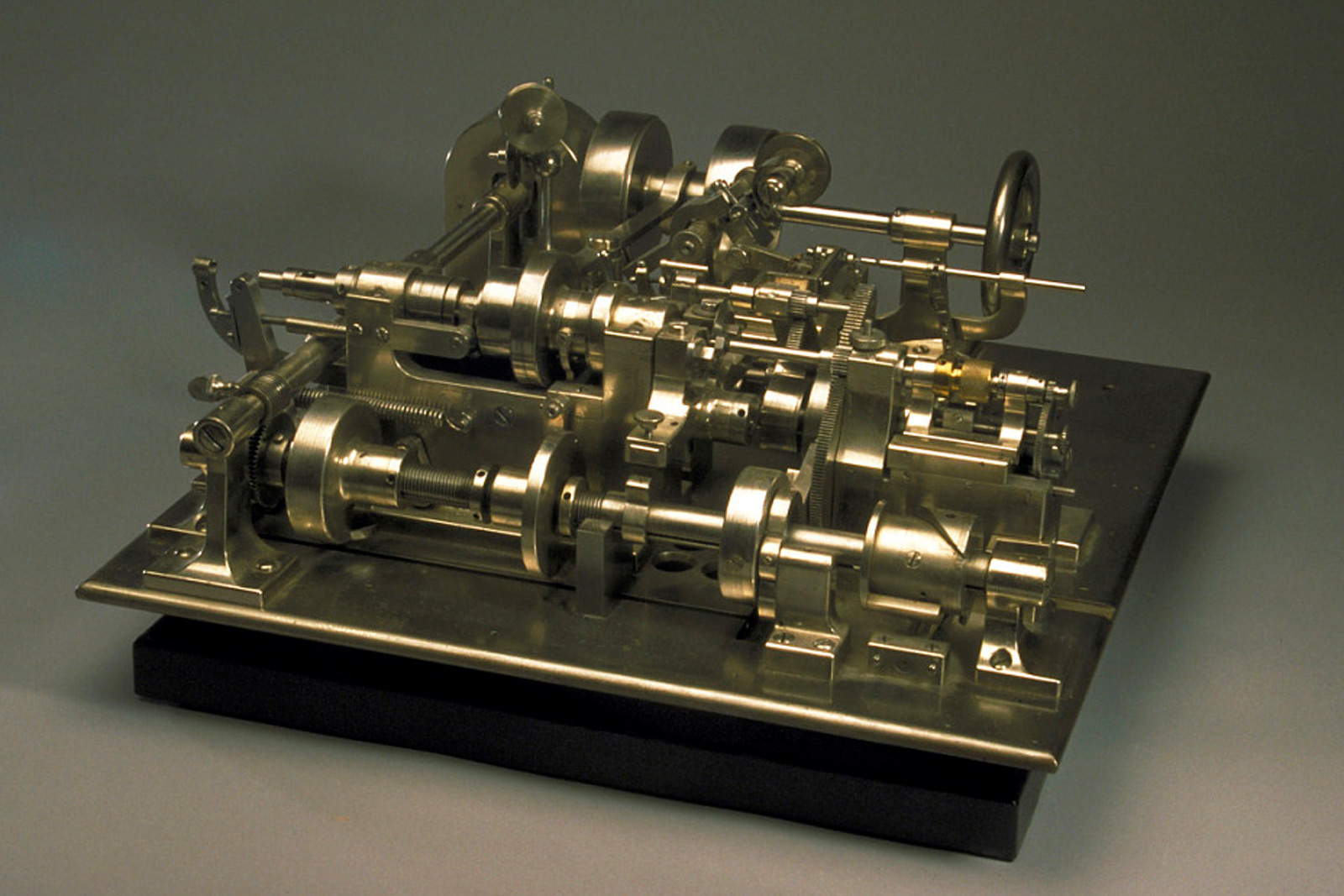

Watchmakers in Switzerland began hearing about exotic new machines, like the automatic lathe invented by Waltham’s own Charles Vander Woerd, which could produce hundreds of identical components per day and were automated to the point that a single technician could operate multiple machines simultaneously.

By the 1870s, automatic lathes like the one pictured above could produce up to 800 identical screws per day, with minimal intervention from the lathe operator. Image – National Museum of American History

Faced with this emerging threat from a key export market, the Swiss watch industry did the sensible thing: they formed a committee and sent a delegation to investigate. Specifically, they sent a team of Swiss engineers to the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876 to gather intelligence and provide recommendations for how to overcome this unexpected challenge.

The Swiss delegation

The Swiss delegation to Philadelphia included Jacques David, the chief engineer at Longines, and Théodore Gribi, who held a similar position at Borel & Courvoisier, a watchmaking firm in Neuchâtel. David and Gribi were astounded by what they encountered at the exhibition and during their visits to the various American watchmaking firms on their itinerary. Upon their return to Switzerland, David summarized their findings in a landmark report (translated to English by Richard Watkins) about what they witnessed on their trip.

The sprawling “machinery hall” visited by the Swiss delegation in 1876. Image – Boston Public Library

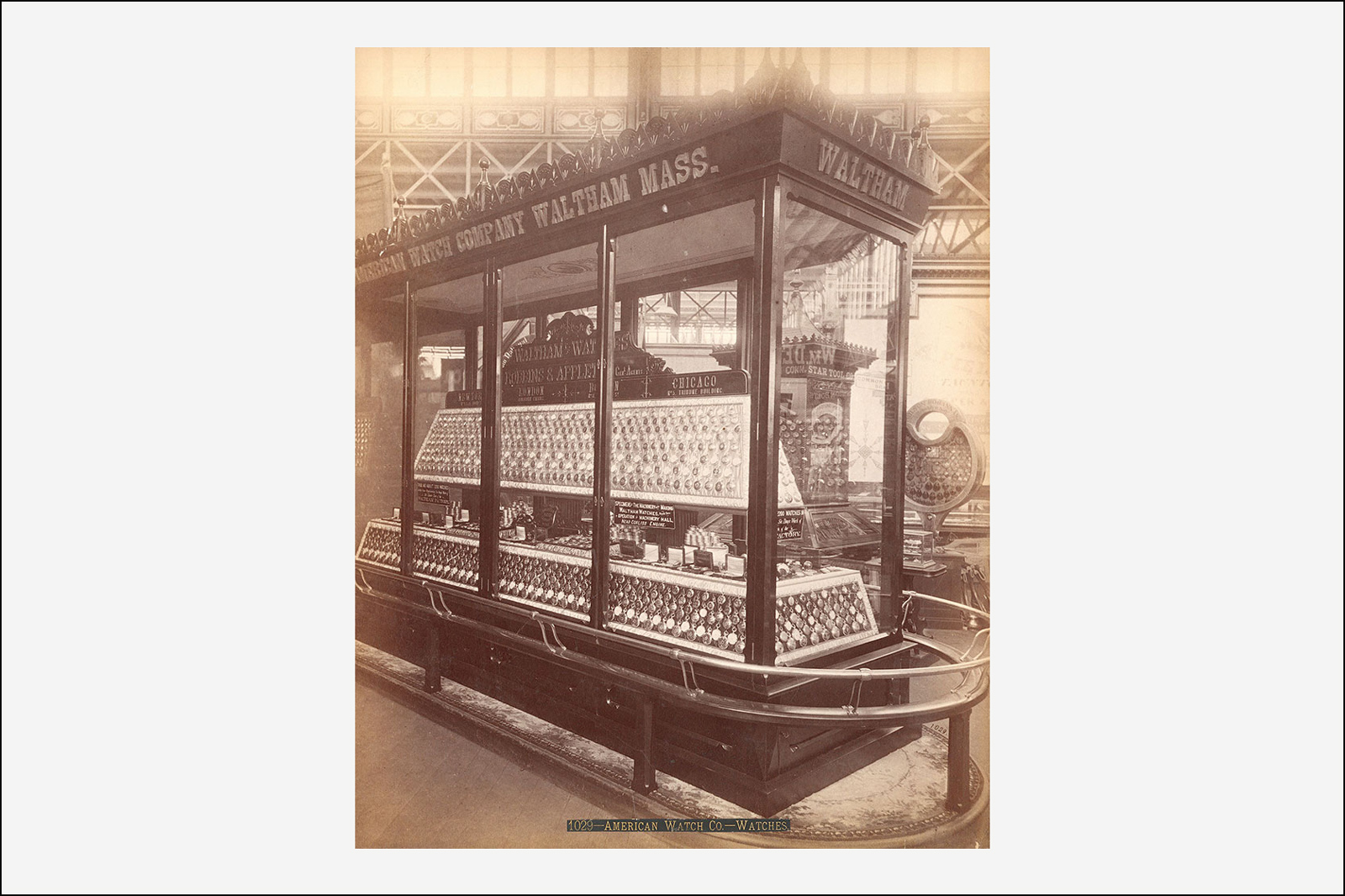

Alongside his translation of David’s report, Watkins included these remarks attributed to Gribi: “I have examined these last days, as an expert for the Jury, the products and tools of the Waltham watchmaking company and I felt admiration, I must confess, while observing both the different kinds and quality of watches, or the wonderful machines and tools this company showed. It must be admitted that we have let our competitors of the New World outstrip us in many respects, and all Swiss watchmakers who come here to make enquiries on that point, without any prejudice, will be soon convinced.”

Waltham’s display of its watches at the Centennial Exposition, as David and Gribi would have seen it. Image – Free Library of Philadelphia

Even their tour of the Waltham factory grounds made an impression, and David’s report describes at length the salaries and quality of life enjoyed by the factory workers.

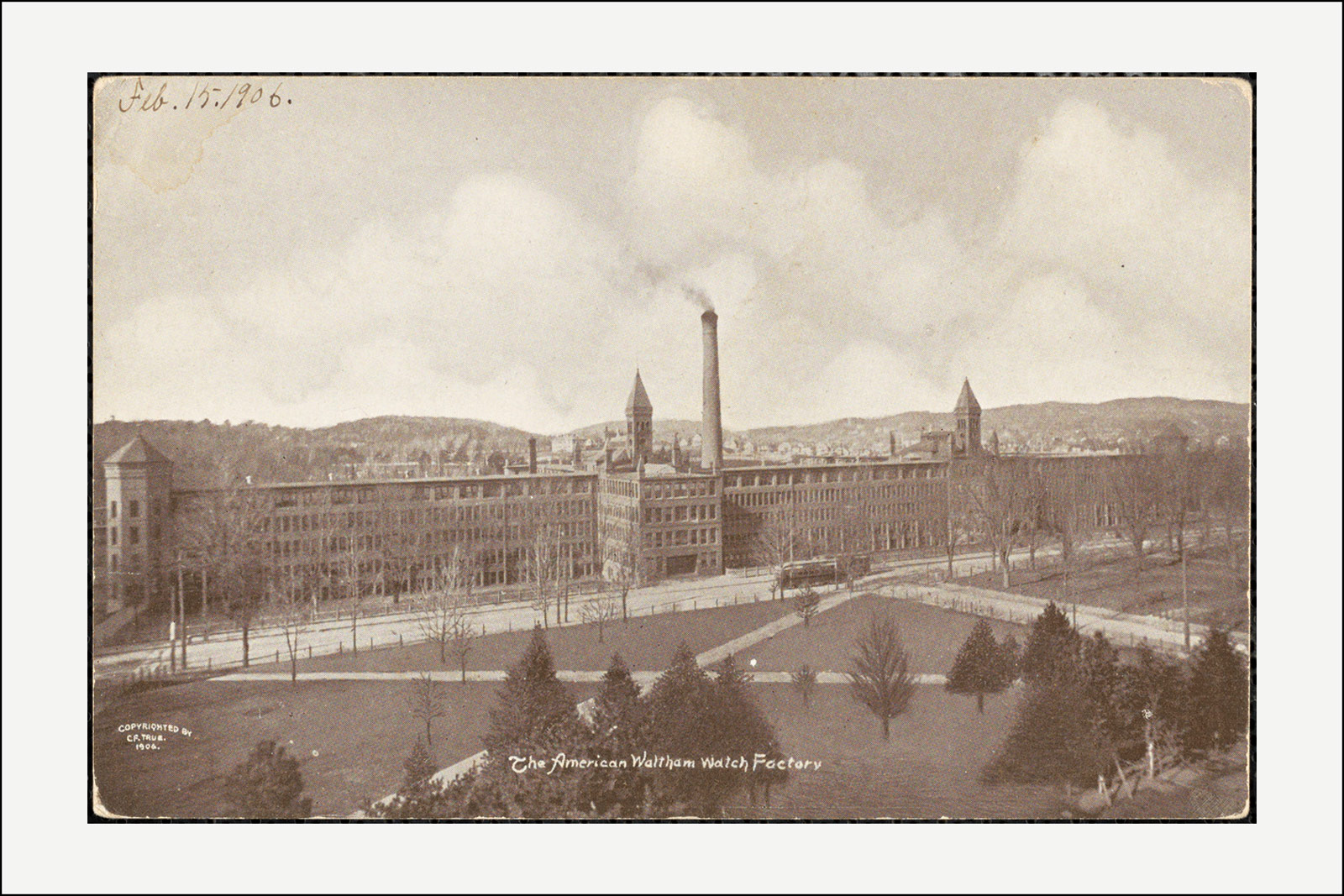

“The buildings of the American [Waltham] Watch Company now cover two acres and easily contain the 900 people who work there. This number could be increased somewhat. The space between the various buildings is occupied by elegant gardens, and very neat lawns surround the establishment.”

“There are currently nearly 300 houses of various types and sizes, but all comfortable. They are mainly surrounded by gardens filled with fruit trees, flowers and lawns, which give this industrial district a remarkable appearance of prosperity.”

The American Waltham Watch Co. factory in Waltham, Massachusetts, in 1906, as it would have looked when Dinko’s watch was made. Image – Digital Commonwealth

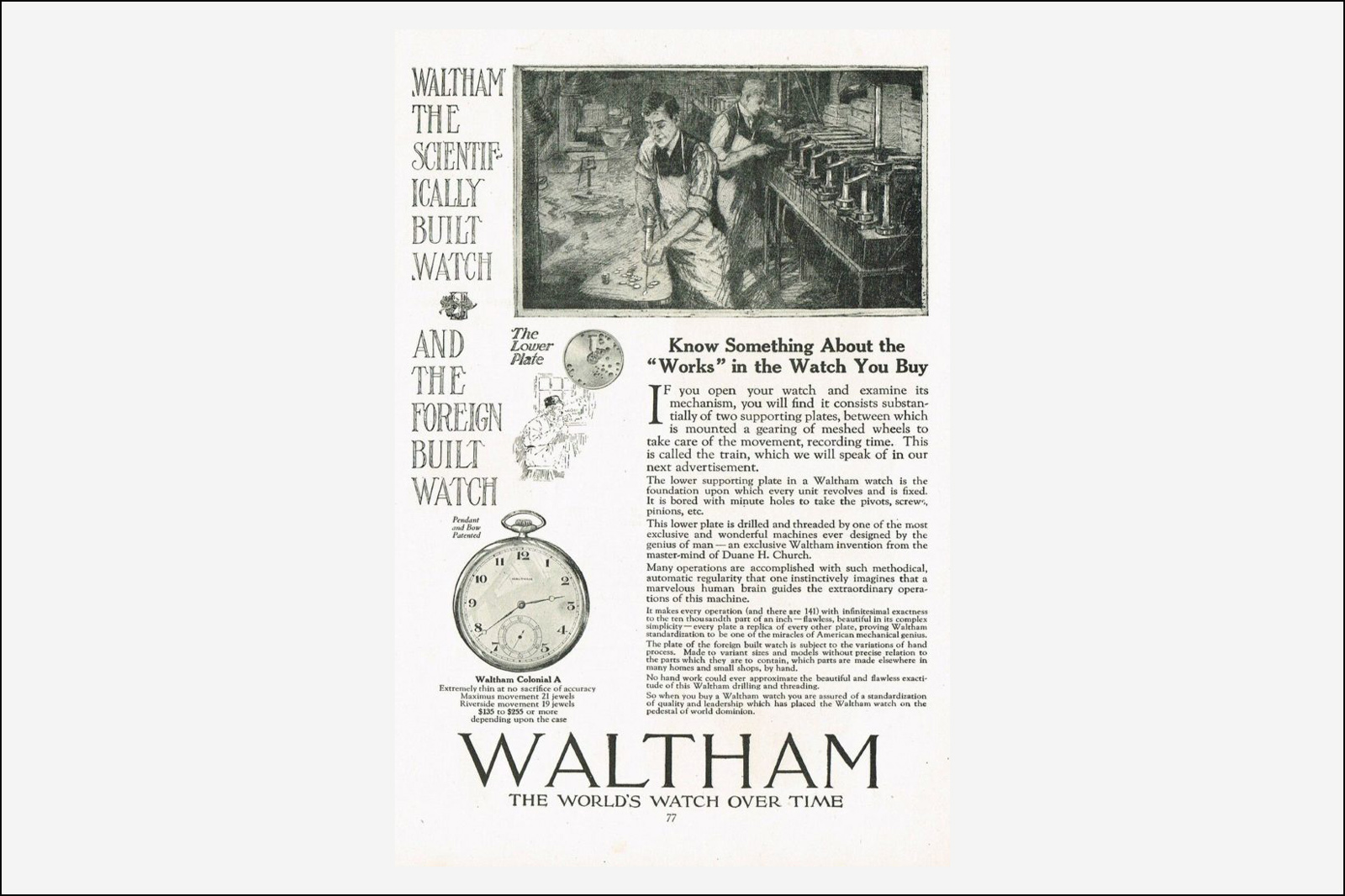

“The scientifically built watch”

David’s report also provided an exhaustive technical analysis of the differences between how American and Swiss watches were produced.

“The assembly of the various parts of the watch, from the barrel to the escapement, is a very easy operation which does not have any resemblance to the equivalent tasks that we know in Switzerland… In all these operations the secret lies in this complete exactitude which makes it possible, from the beginning to the end of construction of the movement, to avoid the labour and difficult tasks to which the Swiss manufacturers devote most time and expense.”

Waltham promoted its products as ‘scientifically built’ to differentiate itself from ‘foreign’ watchmakers. Image – old-pocketwatches.com

And we don’t need to take his word for it. I spoke to Rome-based independent watchmaker Sebastián Salvadó about the quality of these mass-produced American watches that David and Gribi observed.

“If I may say so, American pocket watches are a joy to service. Things just fit like a glove, super smooth and precise,” said Sebastián, “C.H. Meylan from Le Brassus are on the other spectrum, they were using L.E. Piguet ebauches, but boy, you take one of those apart and putting it back together is like walking on eggshells!”

“Pieces just don’t want to fit properly. Even screws don’t want to go back easily”, continued Sebastián, “I got so fed up with these that I stopped collecting them back in the day, even though they’re really beautiful.”

David’s report concluded by recommending profound changes to how the Swiss made watches: “Let us put to one side the bad council of our offended self-esteem and engage in the fight, benefiting from all the advantages which we still have and from the methods that our competitors [in the United States] have discovered. Let us take their tools, imitate their workmen and their methods, but especially let us group together to obtain the kind of progress that the individual industrialist, in his tiny room with his own efforts, cannot achieve.”

A reluctant nation

The Swiss did not like the report. In fact, the report created such a firestorm that it was considered too provocative to publish. Committee members feared that if the American watchmaking firms became aware of the primitive state of the Swiss watch industry, they would launch a marketing offensive that would further erode Swiss market share in key markets.

The most controversial aspect of the report was the recommendation that Swiss watchmakers rationalize production and consolidate into larger, more industrialized factories. Watchmakers feared that these foreign methods would concentrate power in the hands of a few industrialists or, worse still, put them out of work.

The rise of the machines

In the end, resistance proved futile – consolidation and industrialisation continued their onward march. By 1901, the number of factories in Switzerland had increased nine-fold, from about 72 in 1882 to almost 650 in 1901. In 1870, almost 90% of workers in the Swiss watch industry worked from their home workshops, but David Landes notes that by 1905 almost 70% worked in factories with 10 or more staff.

According to a 1912 report by Marius Fallet-Scheurer, the largest Swiss watch factories in 1905 were Longines (853 employees), Omega (724 employees), Tavannes (609 employees), and Zenith (574 employees).

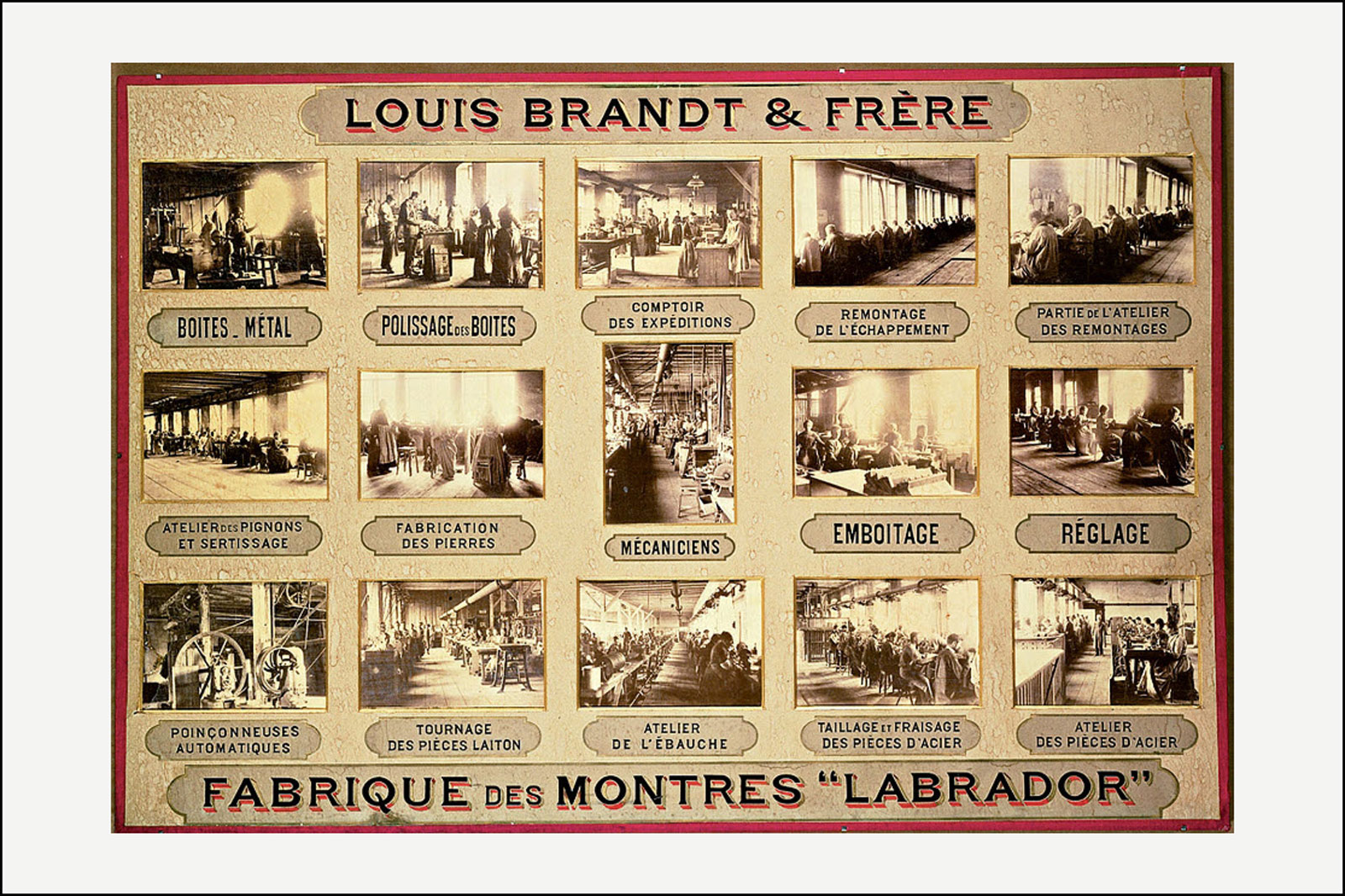

By 1885, Louis Brandt & Frere, which would later be renamed Omega, had built a new mechanized factory in Bienne and adopted many of the mass production methods recommended by David’s report. Image – Omega

Starting in 1896, watchmaking schools started offering courses for machine operators. The first one to offer such a course was the school in St. Imier, home to Longines. Schools in less industrialized cities like Geneva were more reluctant, preferring to pass along traditional techniques of hand craftsmanship, but within 20 years most schools had recognized the need to produce employable graduates.

It was also during this period that the now-legendary Swiss machine tool industry was born, with major names like Hauser, Mikron, and Schaublin all founded between 1889 and 1915.

The Swiss emerge changed, but victorious

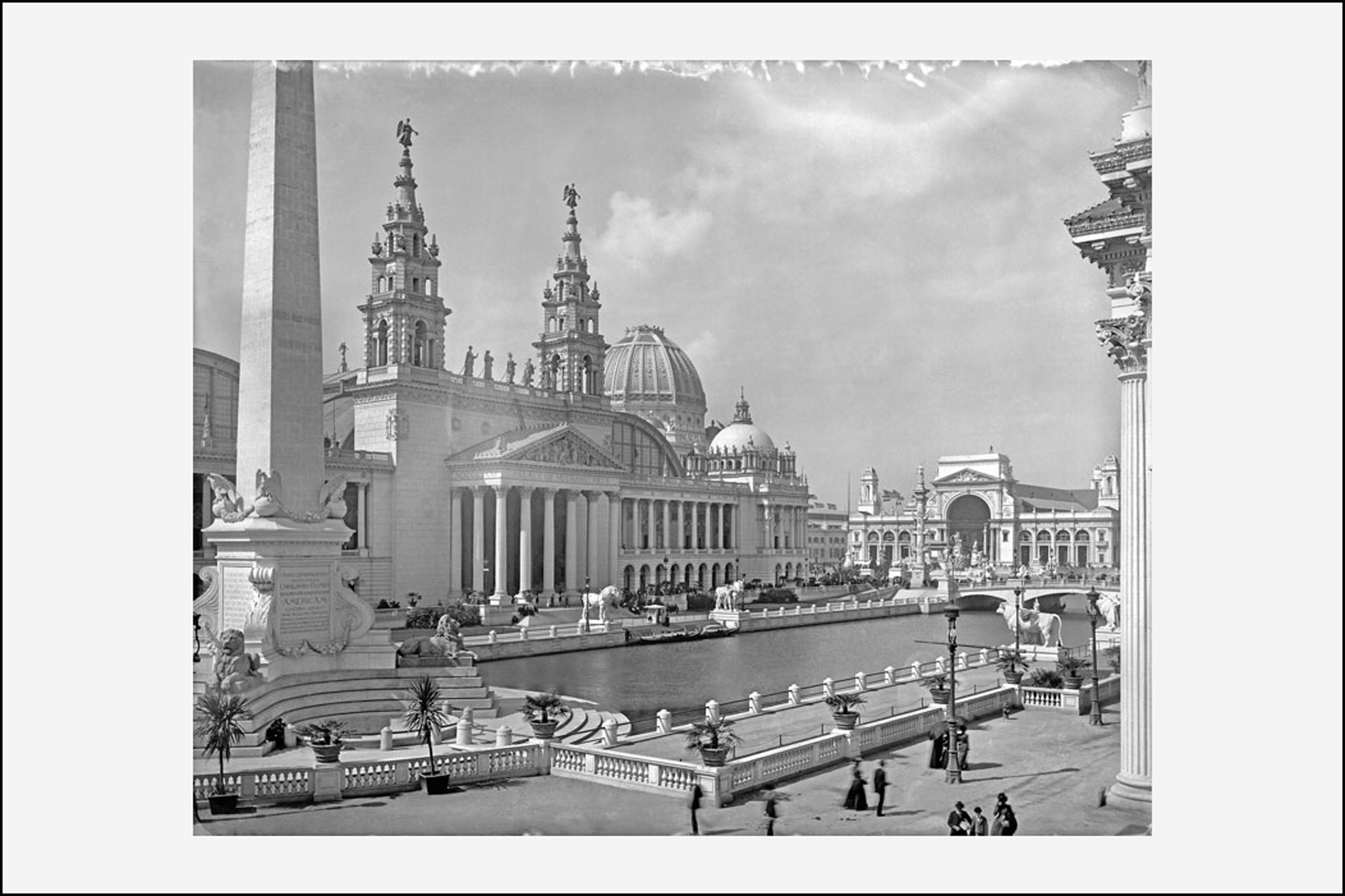

By the time the Chicago World’s Fair rolled around in 1893, the watchmakers of Switzerland had made great strides towards industrial watch production and were more competitive than ever in markets around the world.

A year later, Louis Brandt & Frère introduced the 19-ligne “Omega” calibre that advanced the industry closer to the holy grail of true interchangeability of parts, something that even Waltham had yet to fully achieve. The movement was so successful that Brandt renamed his company Omega.

The Palace of Mechanic Arts at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. This is where Swiss watchmakers introduced the world to their newfound industrial capabilities. Image – The Smithsonian Institution

But the Swiss model of industrialization differed from the American model in one important way. While the Americans sought to build large factories where an entire watch could be made under one roof, the Swiss, with a few exceptions, opted to keep their multi-layered supply chain and instead industrialise smaller factories for the production of specific components.

This ended up being their saving grace because it helped spread the risk across numerous businesses, and enabled the industry to respond more quickly to new innovations and consumer preferences, such as the shift to wristwatches following the First World War.

The profitability of the American firms, on the other hand, depended on making large volumes of just a few types of watches. As such, they were caught flat footed by changing market demands, unable to retool their huge factories fast enough to satisfy their customers.

In a span of about 25 years the Swiss watch industry had changed dramatically. But it had effectively overcome the challenge of mechanization and would remain a de facto monopoly on the world market until the rise of the Japanese watch industry in the late 1960s and the subsequent quartz revolution.

Innovation + time = tradition

It’s important to recognize that much of what we think of today as “traditional watchmaking” was at some point considered disruptive innovation. The most celebrated vintage wristwatch movements of the 1940s to 1960s are products of this post-industrial era, made in mechanized factories that decimated the cottage industry that came before them.

A perfect example is Jaeger-LeCoultre, a brand that today prides itself – rightly – on the traditional know-how it retains. But according to Sebastián Salvadó it was the brand’s own mechanized innovations of the late 1800s that wiped out the then-traditional, entirely manual production of repeater trains in the Swiss Jura.

Even today, the Greubel Forsey Hand Made 1, a watch celebrated for being produced almost entirely “by hand”, is produced using machines, like a Hauser jig borer, that were born to meet the needs of an industry making the transition to mechanized production.

The Greubel Forsey Hand Made 1

Mechanization and the labor force

The industrialization of the Swiss watch industry also helped alleviate some of the problems associated with the lack of skilled workers.

We know that today, the watch industry faces a shortage of skilled labor. Collectors complain about long wait times for service while watchmaking schools are closing left and right. As a collector in my mid-30s, I’m not optimistic about what the service experience will be like 20 years from now. But the shortage of skilled labor in the watch industry is as old as watchmaking itself.

We can see the evidence of this in period accounts and also by the extraordinary innovations that took place in order to mechanize and de-skill the profession so that it could be performed by workers with minimal training. Landes notes that as early as 1741, watchmakers in England had devised machine tools, such as the dividing engine for cutting wheel teeth, that enabled low-skilled workers to produce components “with an exactness which far exceeds what can be performed by hand.”

David’s 1877 report mentions this as well, noting that in Waltham’s mechanized production line, “male or female machine operators can be employed who have no knowledge of the watch industry, and this is another source of economy in the cost price of the product.”

Unfortunately, mechanization and automation in the watch industry is quickly approaching the limit of what modern collectors seem willing to tolerate, and it’s unclear how the current skilled labor shortage will be solved.

An alternative history: the decline of English watchmaking

It’s hard to say what the Swiss watch industry would look like today had it not adopted the American model of mechanization and industrialization, but the English experience may serve as a useful case study.

The English watch industry was once the cradle of horological innovation, having pioneered fundamental breakthroughs like jeweled pivots, temperature compensation, the lever escapement, hairspring terminal curves, the flying tourbillon, the chronograph (as we know it today), and perhaps most famously, the practical marine chronometer. Between about 1750 and 1850, English watchmakers had few equals.

The Centennial Exposition in 1876 wasn’t just an exhibition of American industrial prowess. Businesses from around the world exhibited, including Nicole Nielsen and Charles Frodsham, two of the finest watchmakers in England at the time. Image – Free Library of Philadelphia

But as mechanized production methods and serial production began to take hold in the United States, and later Switzerland, the English were reluctant to change the formula that had led to their historical success.

According to Pierre-Yves Donzé writing in the History of the Swiss Watch Industry, the British Horological Institute “refused to allow the teaching of the use of machine tools to apprentices” and “rejected all proposals for mechanization” in 1880.

As a result, English watches became less and less competitive against state-of-the-art watches from Switzerland and the United States. As David Landes put it, “The more the watch trade lost ground, the more the English consoled themselves with the thought that they were right and their customers were wrong.”

The year 1906 was the last year that an English watch took first prize on home ground at the Kew Observatory and by 1914 the industry had declined largely to obscurity. Though the English continued to make small numbers of fine watches and chronometers throughout the first half of the 20th century, they relied increasingly on Swiss components. The industry was mostly dormant when George Daniels rose to prominence in the 1970s, albeit as a niche maker of a few dozen watches over decades.

The legacy of American watchmaking

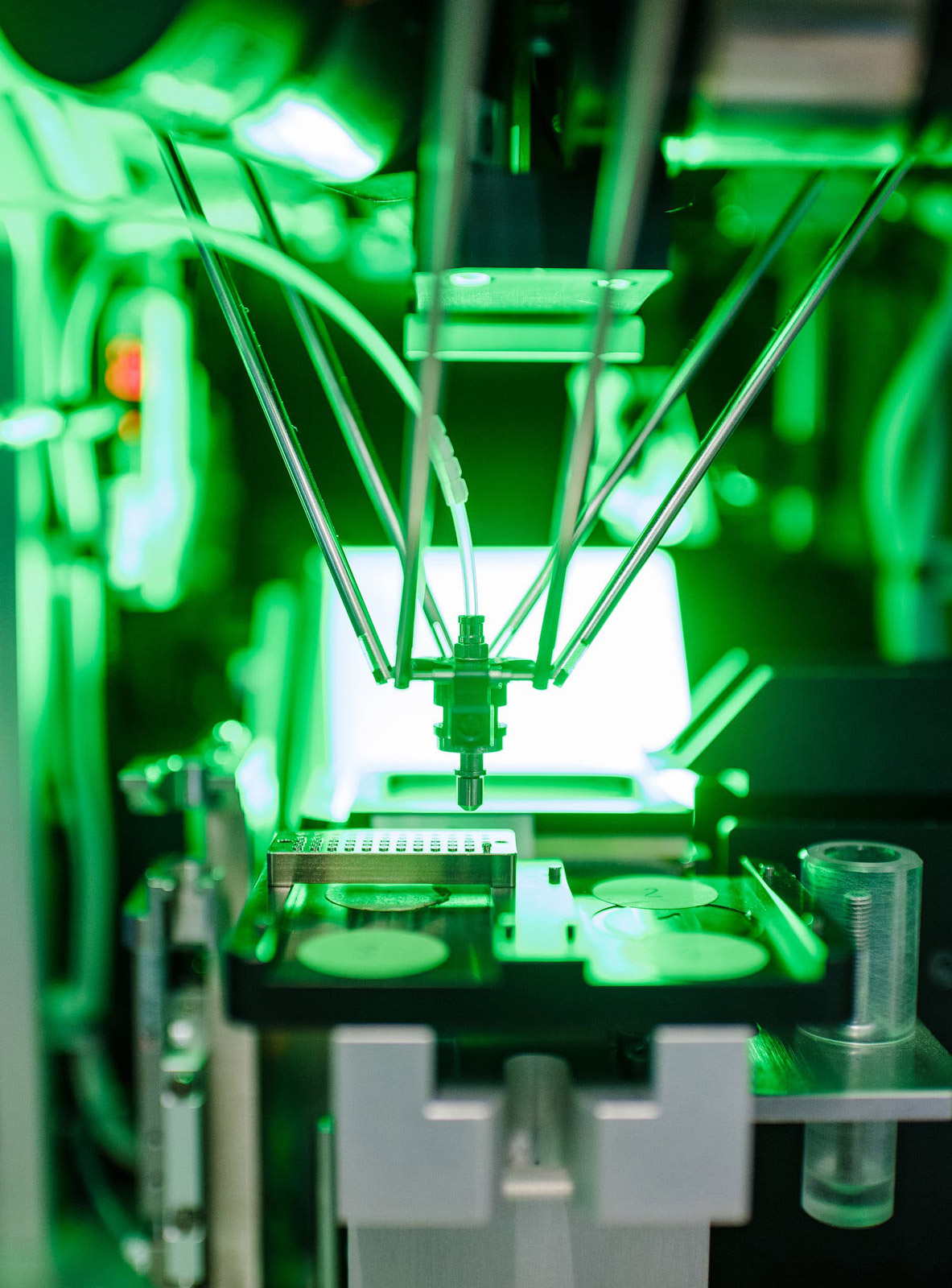

What we do know is that today, most Swiss watches benefit from high levels of automation in various stages of the production process. The watchmakers of Waltham who made Dinko’s watch in 1903 would no doubt be awed by the modern factories of the big brands like Rolex and Omega, but they would probably feel more at home in these cutting edge facilities than they would have in the home workshops of their Swiss contemporaries.

A robot locates a specific part from among 30,000 boxes of components at Omega’s new factory in Bienne. Image – Omega

For example, compare these two accounts of how hairsprings are paired with balance wheels. The first comes from an American factory in the late 1800s, and the second is a contemporary account of the same process at Ulysse Nardin during a recent visit.

In Revolution in Time, David Landes describes the process developed by the American watch companies. “The Americans had neither the time nor the skills [for adjusting the hairspring]. Instead they made large numbers of balances and springs as close to standard as possible; then carefully sorted these [into classes] by weight and force. It only remained then to pair them by choosing from the right boxes or jars.”

More recently, Andrew Hildreth toured the Sigatec silicon manufacture (that is part owned by Ulysse Nardin) and posted the following description to his Instagram account: “Balance springs cut from near the centre of a [silicon] wafer are better quality than those near the periphery. All balance springs are put into one of 60 classes. The average difference in timing between one class to the other: 27 seconds on average for the same balance wheel. Balance wheel and balance spring have to therefore be exactly paired.”

A Waltham watchmaker from the 19th century would be immediately familiar with this process.

A modern sorting robot at Panerai. Image – The New York Times

This speaks to the legacy of American watchmaking and the advanced industrial state of the current Swiss watch industry. While a few elite brands and independent watchmakers continue to sustain some of the pre-industrial methods that existed in Switzerland, France, Germany, and England in the mid-1800s, these methods are largely extinct.

Panerai, to its credit, has gone on-record about this. Its then-chief executive Angelo Bonati explained in an interview with The New York Times, “Today, to show a watchmaker using a metal file is anachronistic. We must tell the truth. Some operations remain manual, but principally we use cutting-edge machines to achieve the results we need.”

Made in the USA: after-sales service

The industrialization of the industry changed not just how watches are made, but also how they are repaired. Today, we take it for granted that when one of our watches needs to be repaired we can send it back to the manufacturer for service, or have a local watchmaker source replacement parts. But this model of after-sales service was pioneered by American watchmaking firms, and was only made possible by the progress they’d made towards the interchangeability of parts.

In his 1877 report, David explained that when it came to American watches, “The merchant can dispense with maintaining a repair shop, which is necessary for Swiss watches. If some difficult problem arises he [can] send the repair to the factory where a special workshop is organised for that purpose. These considerations will push the small watch merchants to promote American watches whose repair is much simpler than that of Swiss watches.”

Waltham today

In its heyday, Waltham went toe-to-toe with some of the best watchmakers in Europe. A Waltham advertisement from 1917 notes that Italy selected Waltham as the official watch for its national railroad network after testing the Waltham Vanguard against “the best watches of London, Geneva and Paris.” This means that when Agatha Christie passed through Trieste and Venice aboard the Simplon-Orient Express, gathering ideas for the novel that would make her career, the conductors onboard the train would have been wearing Waltham watches.

But by that time the American watch industry was already beginning to fall behind on the world market. Landes notes that the value of American watch production peaked in 1890 and failed to grow over the next decade, during which time Swiss exports increased by about 20%.

The seal of the City of Waltham features a depiction of the Waltham watch factory

The Waltham factory produced its last watch sometime in the late 1950s, after years of management problems and financial turmoil. But its cultural significance has been preserved thanks to the establishment of the American Waltham Watch Company Historic District in 1989. In fact, the factory was so important to the City of Waltham that it’s featured on the city’s official seal.

Today, the old Waltham watch factory has been renovated and given a new life as a mixed use residential, office, and retail complex called the Watch Factory. And its current owner has installed a small museum in the building’s lobby outlining the building’s history.

The Waltham factory in 2014. Image – Richard Mandelkorn

The Waltham museum in the lobby of the Watch Factory. Image – Richard Mandelkorn

As for Dinko’s watch, it has found its way into my personal collection where it will be enjoyed for years to come. I’d like to think that “Grandpa Old Man” would be proud to see it given a new life.

Back to top.