Stories: A Legendary Iranian Pilot and His Rolex GMT-Master

Nader Jahanbani of the Imperial Iranian Air Force.

Gunshots ring out with an unnerving cadence, and the chants of angry crowds ring across the city. It is Sunday, February 11, 1979.

Come Monday morning, the country’s biggest newspaper hits newsstands with the front page proclaiming: “The Regime Has Disintegrated”. The provisional government collapsed the day before, with the military having returned to its barracks – leaving the Islamic Revolution triumphant.

All day long that Monday, a young man ignores the revolutionary chaos as best he can, dedicating himself to picking up the phone every hour and dialling his father’s office at air force headquarters within Doshan Tappeh Air Base in Tehran. Each time his father answers and calmly reassures the son all is well.

For a few months now, the son has tried to talk his father into leaving the country. The Shah had already fled and tensions were rising. But each time his old man responded in the same manner, “I am a soldier of this land and my duty calls me to stay.” Not only did the father remain in the country, he dutifully turned up to work every day.

Nader Jahanbani (right) with Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran, in the early 1970s; Nader has his GMT-Master on his wrist

On that fateful Monday, the son calls at six in the evening and hears his father’s voice. He calls again at seven and his father picks up the phone. An hour later, he dials the number once again and listens to the phone ringing. No one answers.

He tries again a few minutes later to no avail. He continues for a couple of hours, until someone finally picks up. The quiet voice on the other end simply states, “They took your father to that school”, referring to the feared Refah School, which had been turned into the headquarters for the revolutionaries.

The father was Lieutenant General Nader Jahanbani, deputy chief of the Imperial Iranian Air Force (IIAF), who was arrested on the eve of final day of the Iranian Revolution. A month later, he was executed aged 50, leaving his Rolex GMT-Master in a locker at Tehran’s Qasr prison for his son, Anushiravan.

The Rolex GMT-Master ref. 1675 “Mark III” with a “Radial” dial once owned by Nader Jahanbani and now worn by his son

A military man

Nader Jahanbani was born on April 16, 1928 in Tehran, into a military family of royal lineage, making a career in the air force his inevitable destiny.

One side of his family was descended from the Imperial dynasty that ruled Iran before the Pahlavis, and the other was related to Russian aristocracy via his mother, Helen Kasminsky.

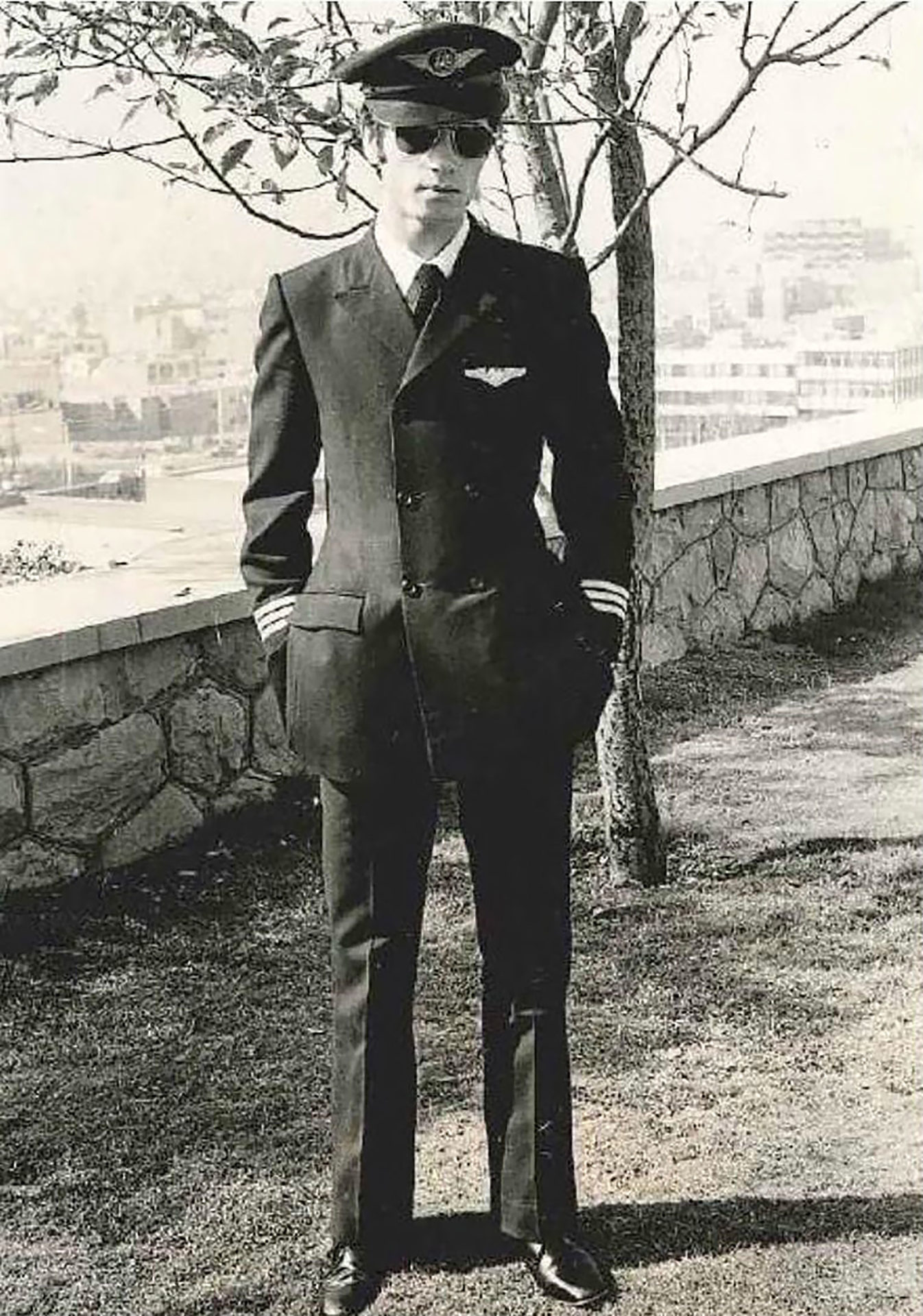

A young Nader Jahanbani in his flight suit

His father was Lieutenant General Amanullah Jahanbani, a great grandson of Fath-Ali Shah, a king of the Qajar Dynasty, which ruled Iran from the late 18th to early 20th century.

During the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi, the father of the last Shah of Iran, Amanullah commanded the Persian Cossack Brigade, and was later a cabinet minister. Though Amanullah was thrown in prison late in the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi, he later regained favour under the next Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who released Amanullah and then appointed him senator.

Around that time, Amanullah sent Nader to the Russian Air Force Academy, where he graduated and then joined the IIAF in 1950 – the beginnings of an illustrious career that would see him rise to become one of the most influential figures in the country’s air force.

A few years after graduation, just as the IIAF was about to receive its first fighter jets, the F-84G Thunderjet, Nader and 13 of his fellow pilots were dispatched to Fürstenfeldbruck Air Base in Germany, where the German air force had its the Officer Training School.

Nader Jahanbani (first row, second from left) and his class at the Russian Air Force Academy

The trainees all underwent the same course, but Nader was one of five pilots who stayed behind after completion to attend the Jet Pilot Instructor course. It was then that Nader witnessed what was then the world’s best aerobatics team, the Skyblazers of the United States Air Force.

The Iranian and American pilots soon made friends, and Nader became a regular in the back seat of the jet flown by the Skyblazers’ leader, a Major Smallen, giving Nader a firsthand look at the technique of the experienced American aviator. It was at this moment, high in the sky above Southern Germany, that Nader decided that the IIAF should have its own aerobatics team.

Nader Jahanbani (centre) with teammates in front of an F-84G

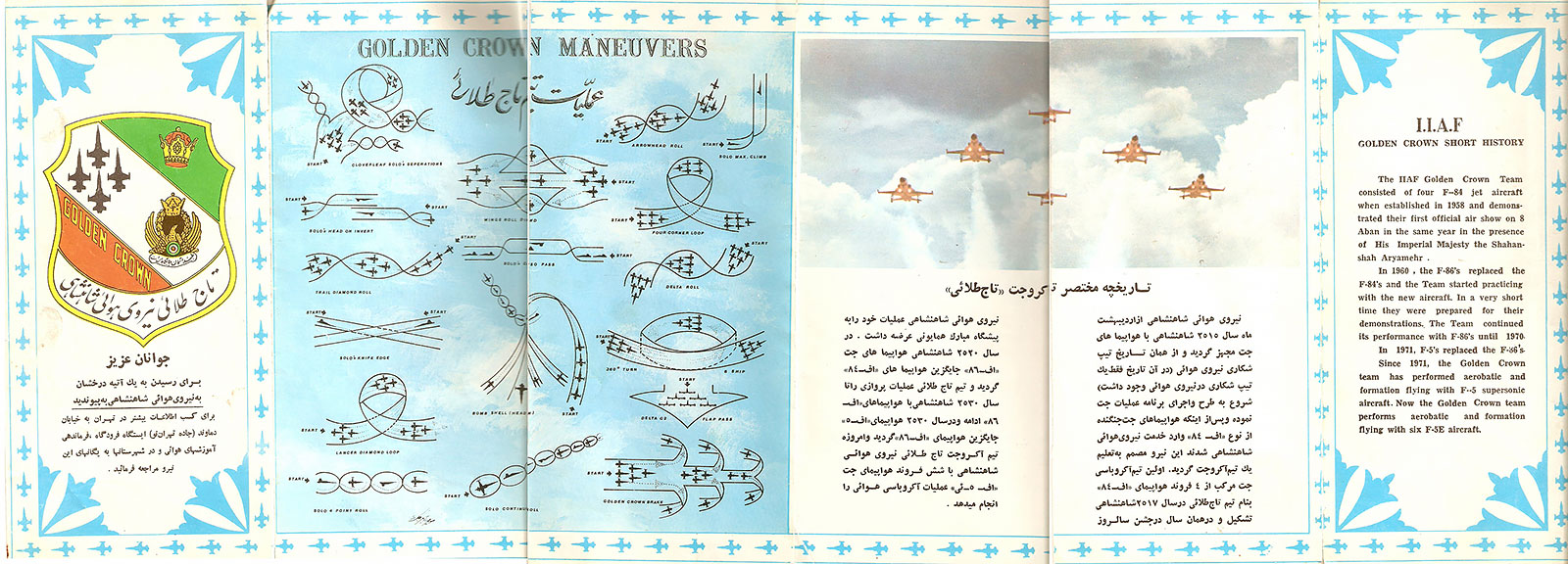

Once back in Iran, Nader set about forming an aerobatics team. His fellow pilots and even the chief of the IIAF backed him, leading to the inauguration of the Golden Crown AcroJet Team in June 1958.

With almost nonstop training, the Golden Crown qualified for the world championship just a year later. Against the odds, the team triumphed over the American and British competition to clinch the championship in 1959. From its founding until the revolution, the Golden Crown maintained its position as one of the best aerial acrobatics teams in the world.

A period brochure for the Golden Crown

An F-86 Sabre jet of the Golden Crown

While winning the aerobatics championship was the greatest achievement by the then 31-year-old Nader, he would go on to become a key figure in the IIAF over his career. Tall, handsome, and very much a military man, Nader trained junior pilots and helped refine the strategic plans of the IIAF.

With the connections he built at the court of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Nader was eventually elevated to deputy commander of the IIAF. And in the final year of Pahlavi dynasty, he was appointed the president of the national Sports Organisation, during which the country’s football team qualified for the World Cup for the first time.

Nader Jahanbani (fourth from left), with members of the Golden Crown

The pilot’s watch

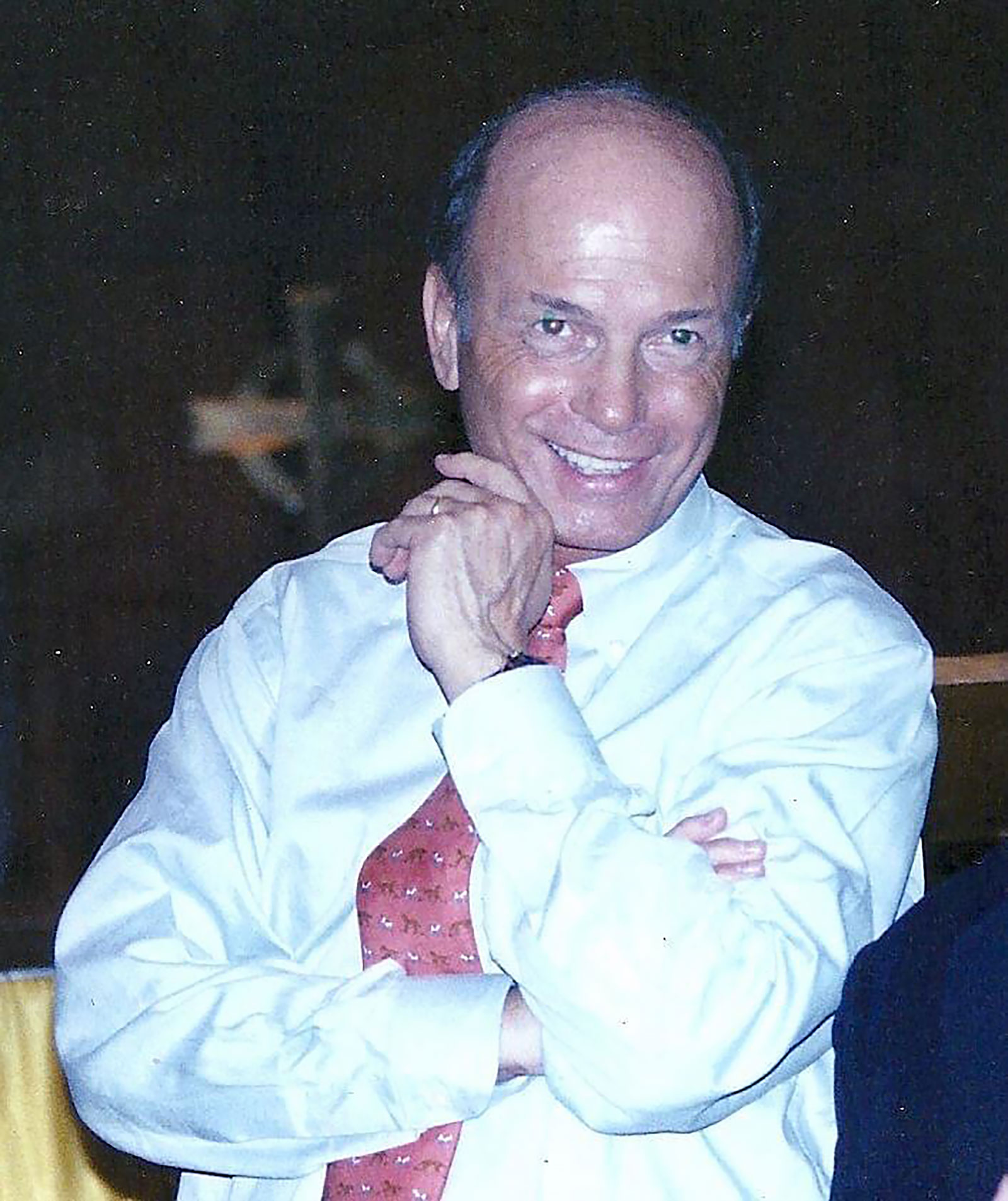

Anushiravan Jahanbani is one of Nader’s two children. Now in his eighth decade, Anush lives in the United States, having retired from a long career at lighter manufactures Ronson and Zippo.

Anush lived much of his early life outside his home country. He was born while his father was studying in Russia, and then lived in Germany from the ages of 11 to 19 while Nader embarked the officer training course.

Once he returned to Iran as a teenager, Anush could not leave the country due to mandatory military service, where he served in the air force.

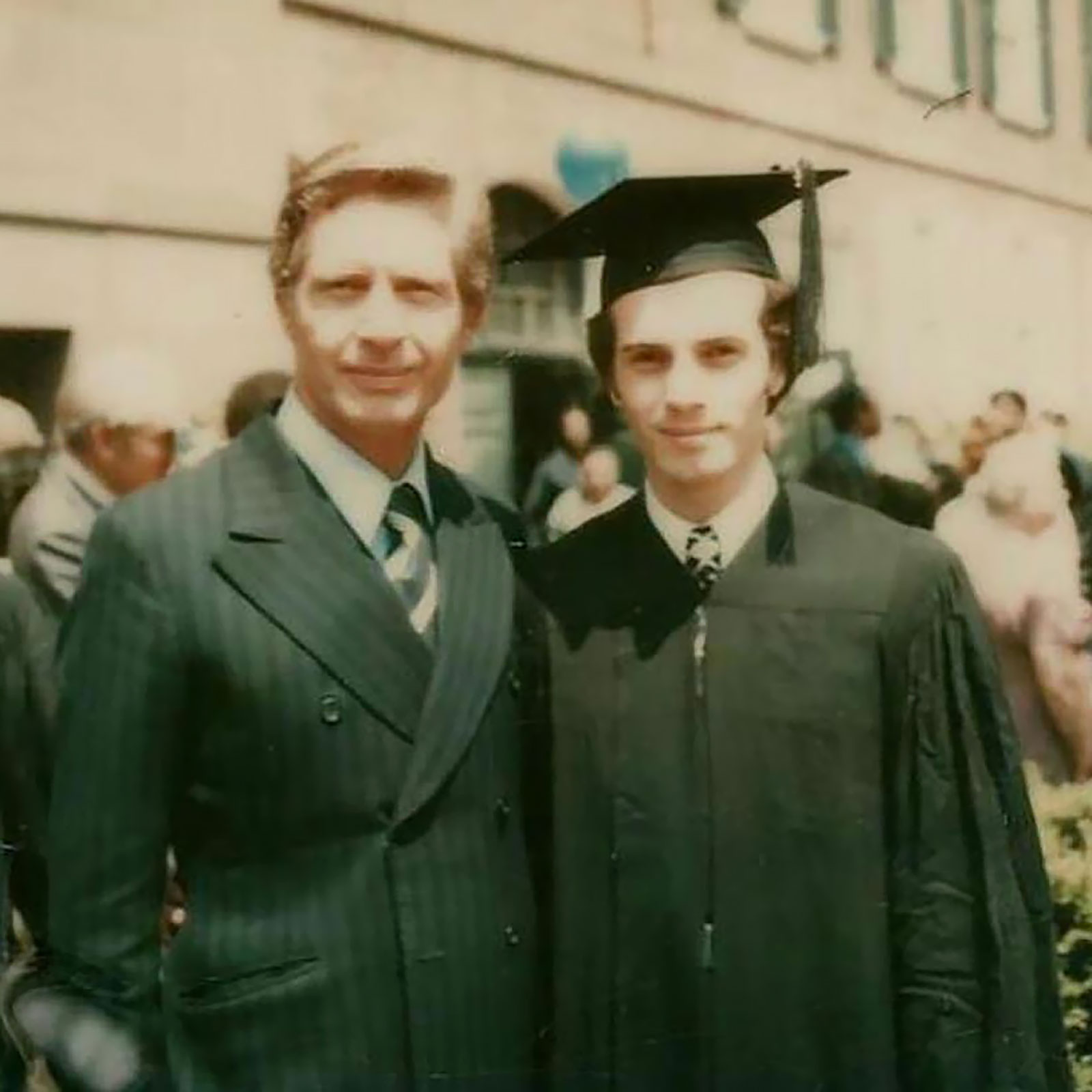

Nader Jahanbani at Anushirvan’s graduation

“My initial pilot training was completed when I was 16, then my father gave me his old GMT-Master and bought another one for my coach as a gift”, he says.

Anush then chose flying as a career, but not in the military. After completing his military service and flying a crop duster plane for several months, he left for Texas, where he earned an airline transport pilot license, the highest certification a pilot could obtain.

“Once I got my [flying] degree, I went to Yale University and studied economics”, he says, before returning to Iran to start Air Taxi, an airplane charter and maintenance outfit. Air Taxi soon became the carrier of choice for the Shah and his court, along with senior government officials and country’s wealthy elite.

“The first watch I got from my father was when I became a pilot; he took off his GMT-Master and put it on my wrist right away. The next one was a Day-Date he gave me when I got married,” says Anush, “But the watch I have now is a different one: the GMT-Master he bought later in Europe, which was passed on to me after he was executed”.

Of all the items left behind by Nader, Anush considers that GMT-Master his “most important property”.

“My father was always been a God to me. Looking at and wearing this watch gives me a mysterious amount of energy – an energy that has not diminished in the last few decades,” declares Anush, “I have the watch on, even when I sleep.”

“Every time I look at it, I have no choice but to think of my father; thousands of memories parade before my eyes,” Anush continues, “I remember the times we flew together; I remember the time we were in the car together and I lucidly remember him driving. I remember the light beam that passed through the car window and reflected on the crystal.”

“The watch he always had on his wrist and now I always have on mine,” says Anush, “From the moment I received his Rolex and uniform from his prison guard, I never bought or wore another watch again, not even the Day-Date he had given me.”

Anushiravan Jahanbani in his Air Taxi uniform

Incidentally, Anush hates the “Pepsi” nickname for the blue and red bezel; every time someone uses that nickname, he corrects them, emphasising the GMT-Master is a “pilot’s watch”.

And as for the prosaic issue of timekeeping in the years he has worn it, Anush notes, “About 20 years ago, I noticed that it was a little slow, so I sent it to the company for service and in the service-request letter, I strongly insisted that they should be careful not to lose it. After three weeks, the watch was returned as it was on day one, with a bezel and crystal replaced.”

The calm before the storm

The memories evoked by the GMT-Master are warmly reassuring, but the events that led to the watch being handed from father to son are tragic.

“For several months before the revolution, there was tension in the air and you could sense something was going to happen,” says Anush, “I took my family to Germany and my absence in Iran was indeed a relief to my father; he had insisted that the whole family go abroad.”

I put the question to Anush: why didn’t his father leave Iran, especially since the Shah had already departed well before Ayatollah Khomeini returned?

“He could not be convinced to leave Iran,” Anush replies with regret. “My father was meant to be in Iran, his home,” he continues, “Even if he left, he could never find peace. He would have either become depressed or killed himself. The good thing about his destiny is that he never got old and he is and will always be the handsome Nader Jahanbani captured in photos.”

The Shah of Iran, Nader Jahanbani and other dignitaries welcoming a foreign dignitary to Iran in the early 1970s

“Although I knew my father wanted me to be out of Iran, I returned to Tehran exactly one day before [Ayatollah] Khomeini returned from exile,” recounts Anush.

“As soon as I arrived, I went to my office in Air-Taxi and called my father. When he heard my voice, he said that he was very happy that I was not in Iran,” says Anush, “I knew I was giving him bad news, but I told him I was in Tehran.”

“I clearly remember him being silent for at least a minute, and I could feel the worry in his silence. Then he said, ‘I’m sure you know what you are doing.'”

I asked Anush if he thought it was the right thing for him to have returned all those years ago?

“Two weeks after [my father’s] execution, I was arrested and imprisoned for five months,” says Anush, “However, I remember the evening I returned [to Tehran], my father came to see me and I could see he was beaming with pride. I could feel that he was happy deep down to be by his son’s side.”

“We had exactly 10 days to be together – the interval between the return of [Ayatollah] Khomeini from exile to the day the revolution claimed victory,” remembers Anush, “Me being back and by his side had given him such joy. There was tension and anxiety in the air, and it was clear that things were going to deteriorate, but my father and I seemed to be somewhere else celebrating our golden bond.”

Nader Jahanbani with his wife and children, with Anush on the right

The 10 days passed quickly. Those anxious telephone calls that counted down to the end of his father’s career took place on February 11, 1979, as the Pahlavi dynasty was in its final days. It was at the dusk that several revolutionaries broke into Doshan Tappeh Air Base and arrested Nader Jahanbani. He was taken to the Refah School, the nerve centre of the revolution where the most important prisoners were detained – and some executed.

I ask him if he thinks Nader had foreseen his arrest. “Without a doubt, my father knew he would be arrested,” Anush responds, “And I for one, believe there were no bones about him being executed”.

“Maybe it was because of this awareness and confidence that he neither cried nor begged for his life unlike many other imprisoned officers,” explains Anush, “My father’s cousin was also in the custody of the revolutionaries at the time, and he always said that every time he saw Nader, he had a calm face and firm demeanour, as if he did not care about the horrible and deadly situation he was in.”

The end, and the beginning

History has it there were no explicit charges against Nader, who was executed with urgency. In court, he sat with a piece of paper around his neck bearing the label “Agent of Corruption”. More to the point, there are no reliable reports or documents from his brief imprisonment and trial, except for a column in a newspaper that narrated a part of his conversation with the judge.

Perhaps because of his illustrious career and swift death, legends have grown around Nader since his passing. “There have always been many stories about my father; whether from his time in the air force, his time in prison, or his trial and execution,” says Anush, “The fact is that none of these alleged stories and narratives can be substantiated. There are still many who say that he once crossed the Karun Bridge in a fighter jet, or that he commanded the firing squad to shoot when he was executed. But as his son, I never cared about such allegations.”

The March 14, 1979 copy of Ettelaat newspaper, with the front page (left), and the coverage of Nader’s trial (right); he is visible in the rightmost photo

“The only thing that makes sense to me is that my father answered all the questions the judge asked him in court, responding properly in short, decisive sentences – this is what the newspapers reported,” says Anush, “I can believe that, because this depicts precisely my father’s brave, strong and tough personality; he was an officer and a gentleman.”

“A week or two after my father was executed by firing squad, which was blatantly conveyed to us by the radio news, I was arrested and spent five months in prison,” says Anush, “I was charged with being the son of Nader Jahanbani, and they waited five months for someone to come and lodge a complaint against me so they could issue a verdict on the pretext of the complaint. Not only did no one show up, but also my colleagues at Air Taxi all signed a statement in my support.”

“During my imprisonment I heard a story about my father,” recalls Anush. While still in prison, Anush was blindfolded and sent to a visitor’s room to meet his mother. The guard accompanying him asked in a low voice, ‘What is your relationship with Lieutenant General Jahanbani?’

‘I am his son,’ Anush replied. A quiet moment passed before Anush asked, ‘Did you see my father?’

‘I was your father’s jailer’, replied the guard, who added, ‘I have never seen anyone so brave, he was tough as a stone’.

The Legacy that Endures

I ask Anush why, unlike so many other Iranian exiles, he does not speak to the media about his father. “My father does not need our narrations,” says Anush, “His career is his best spokesman, and it says enough about his great character.”

There are numerous groups on Facebook dedicated to Nader Jahanbani, so I ask Anush why he thinks his father remains a charismatic figure even decades later.

“I have often asked the admins of those pages on social media the same question,” says Anush, “Most of them were born after the 1979 revolution and never even lived in his time, but they say it is Nader’s courage and bravery that inspires them.”

Nader Jahanbani (centre) with Golden Crown pilots

I also asked what he would do if he returned to Iran. “If one day the situation prompts me to return to my homeland,” replies Anush, “The first thing would be to go to my father’s grave – there are many things I wish to tell him”.

“The main reason I remain loyal to this watch is that every time I see it, it reminds me of the thousands of memories of my father. That is why I will never be willing to keep track of time with any other means other than this dear relic,” Anush admits.

Anush Jahanbani

I think about his father’s story and ask a question that is very important to me: “What will happen to this watch?”

“I will pass this watch on to my grandson, who is 12 now – that is in my will, in black and white.”

And Anush adds, “My grandson’s name is Nader… This watch will always belong to Nader.”