Book Review: The Independent Spirit – Time Makers Since 1985

Documenting the AHCI and its members.

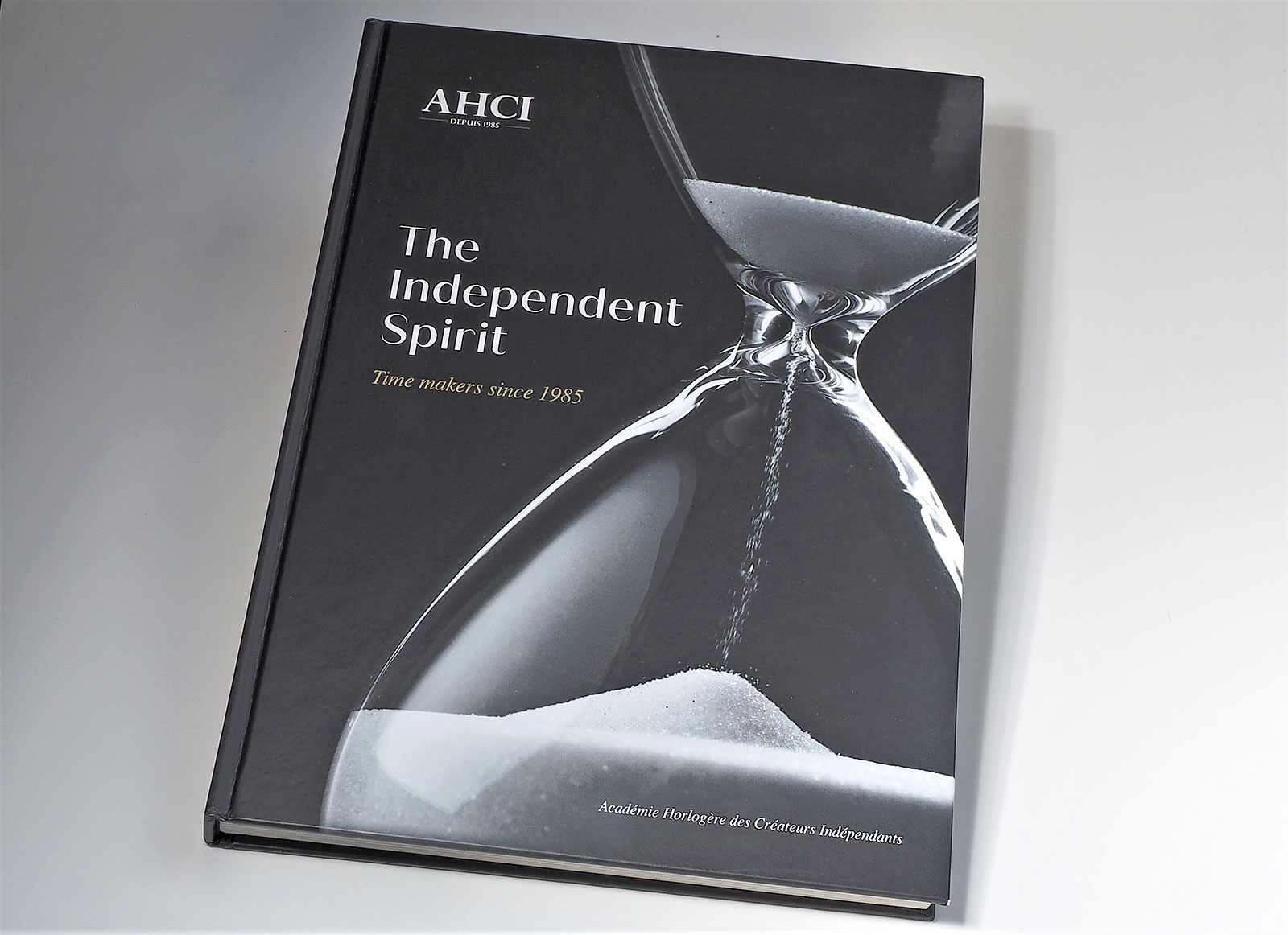

The Independent Spirit: Time Makers Since 1985. By Olivier Muller. AHCI.ch; CHF75.00

Conceived by the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants (AHCI), the new book on independent watchmakers wants to address the persistent problem the founding members sought to remedy when they set up the association in 1985.

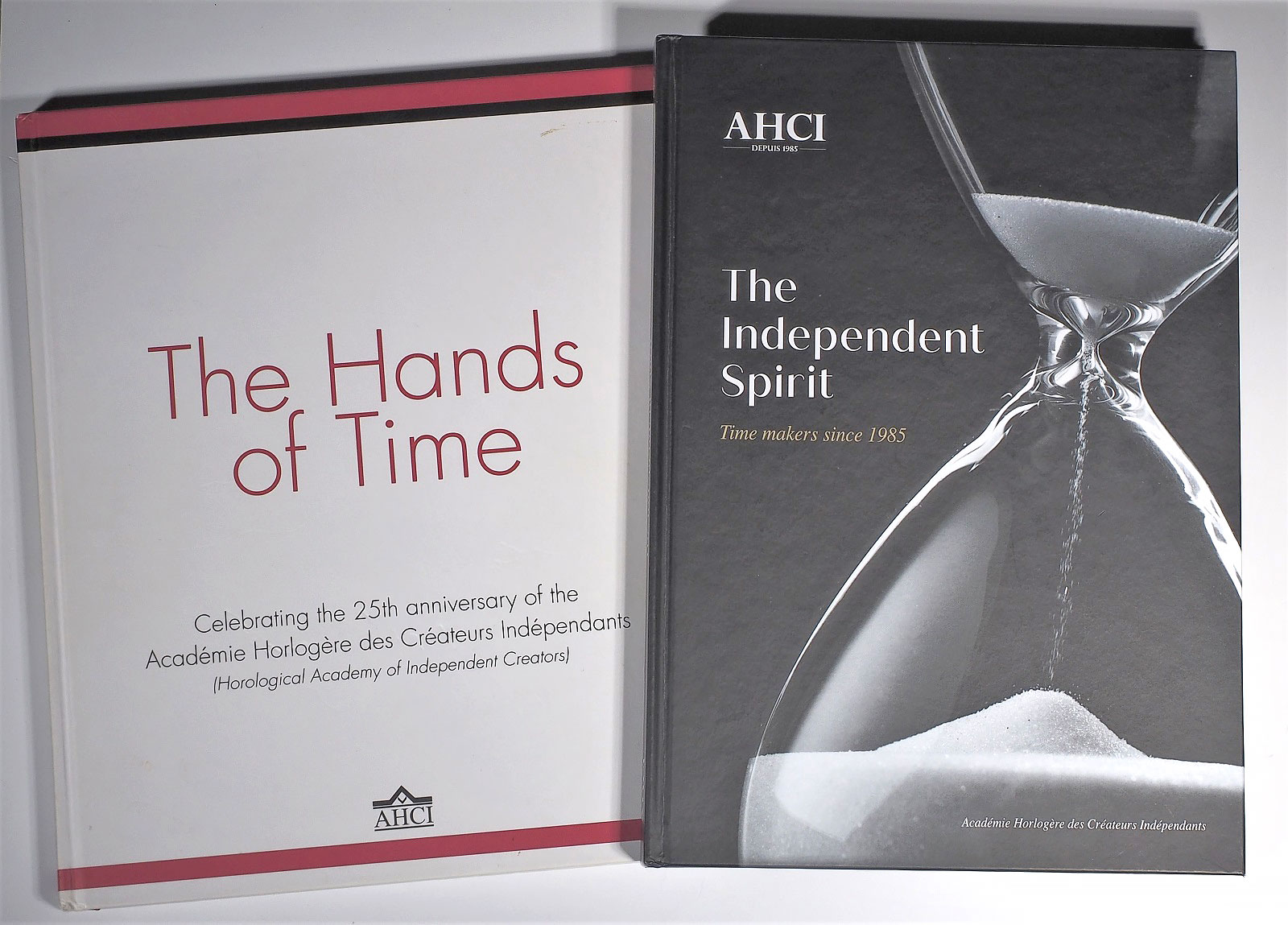

Svend Andersen, one the two cofounders along with Vincent Calabrese, aptly describes the book in the foreword as a publication to raise awareness of independent watchmaking in a manner that’s not available from the mainstream watch press. In essence, the book is an update to The Hands of Time that was published 10 years ago for the AHCI’s 25th anniversary. Like the decade-old edition, the new book serves mainly to market the association’s members, with its structure being familiar to anyone who has seen the booklets that the AHCI has occasionally published, with each member is granted equal real estate to explain his work.

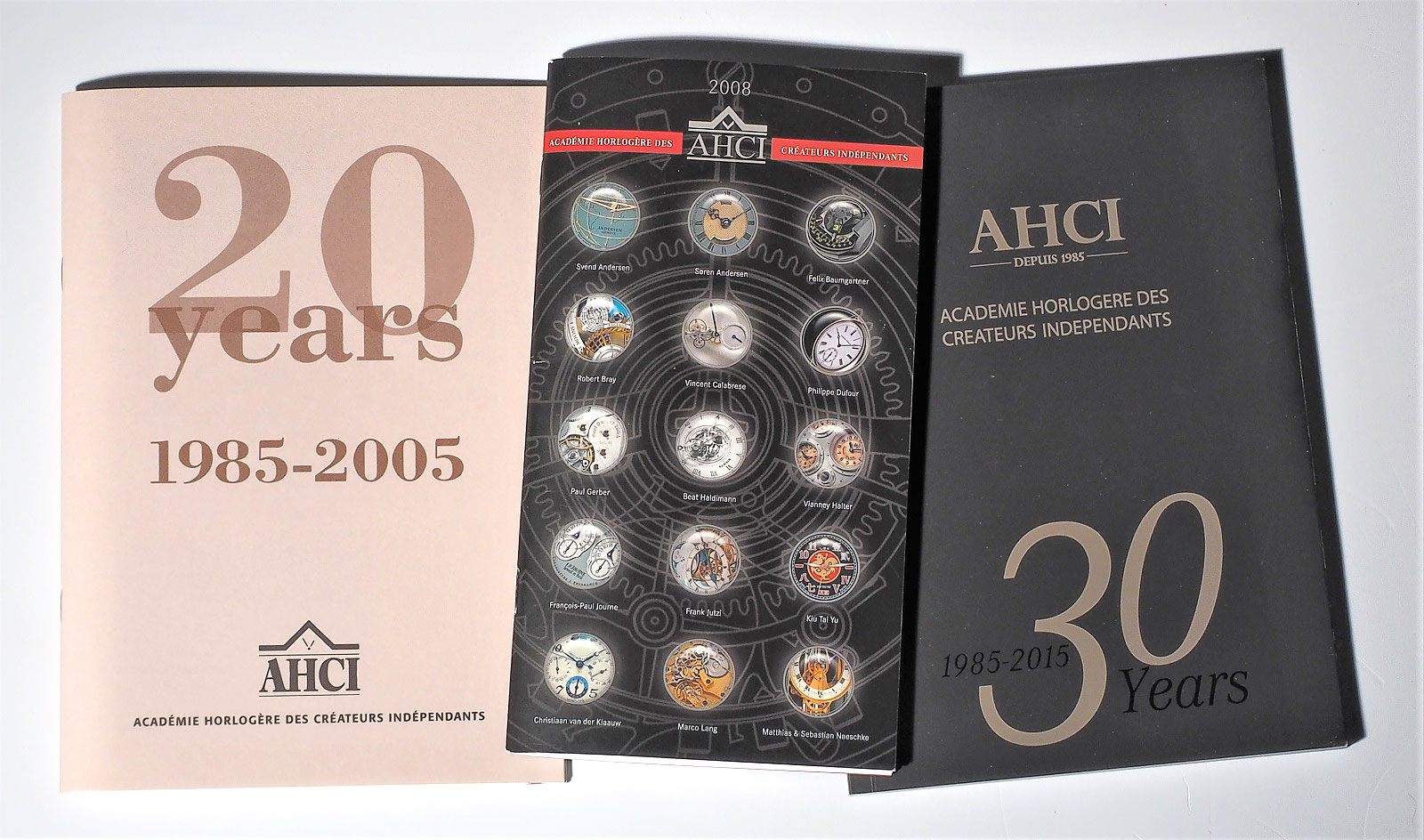

The anniversary book of 2010 (left), and ‘The Independent Spirit’

A selection of AHCI booklets published over the last two decades

In their own words…

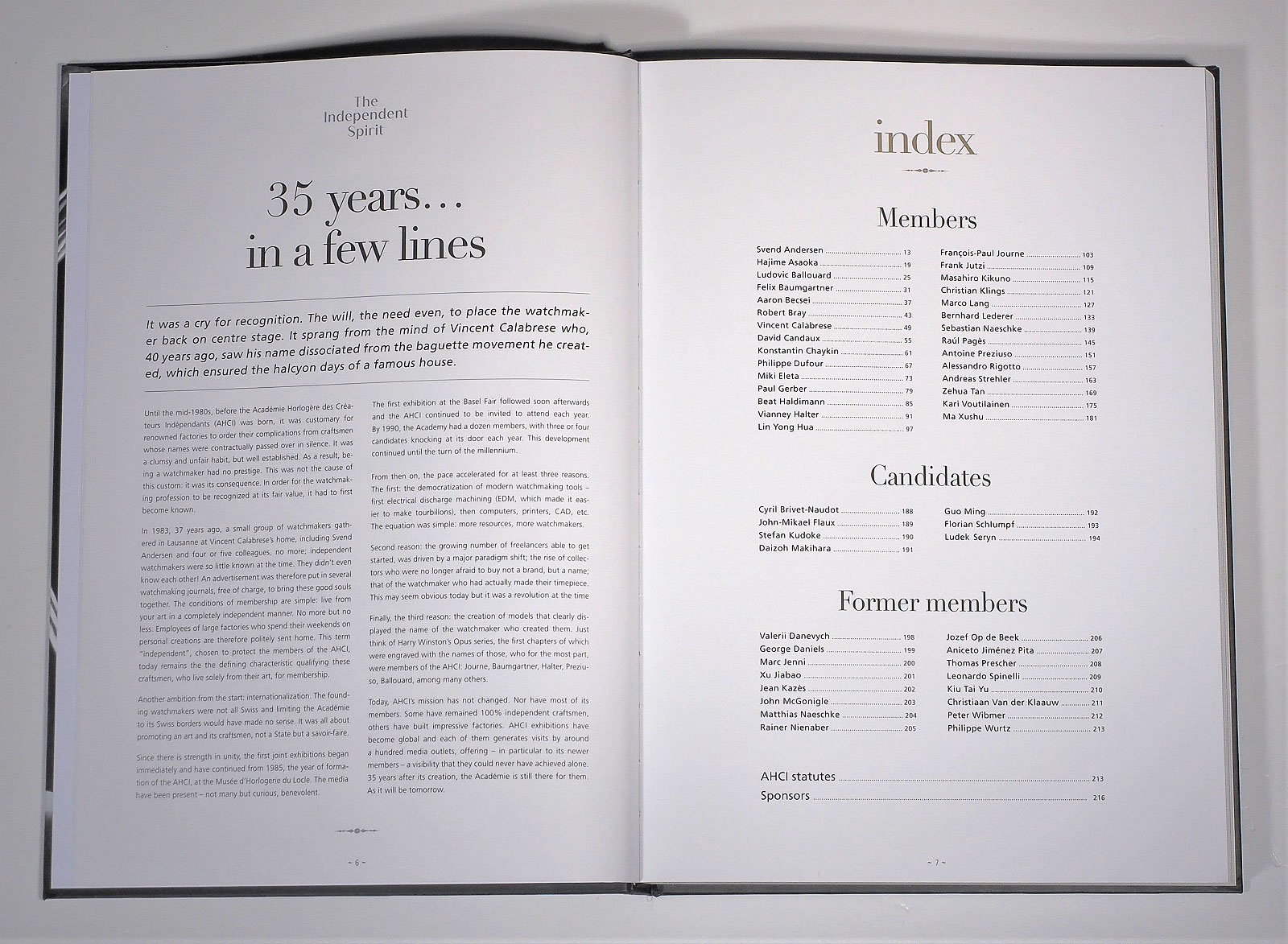

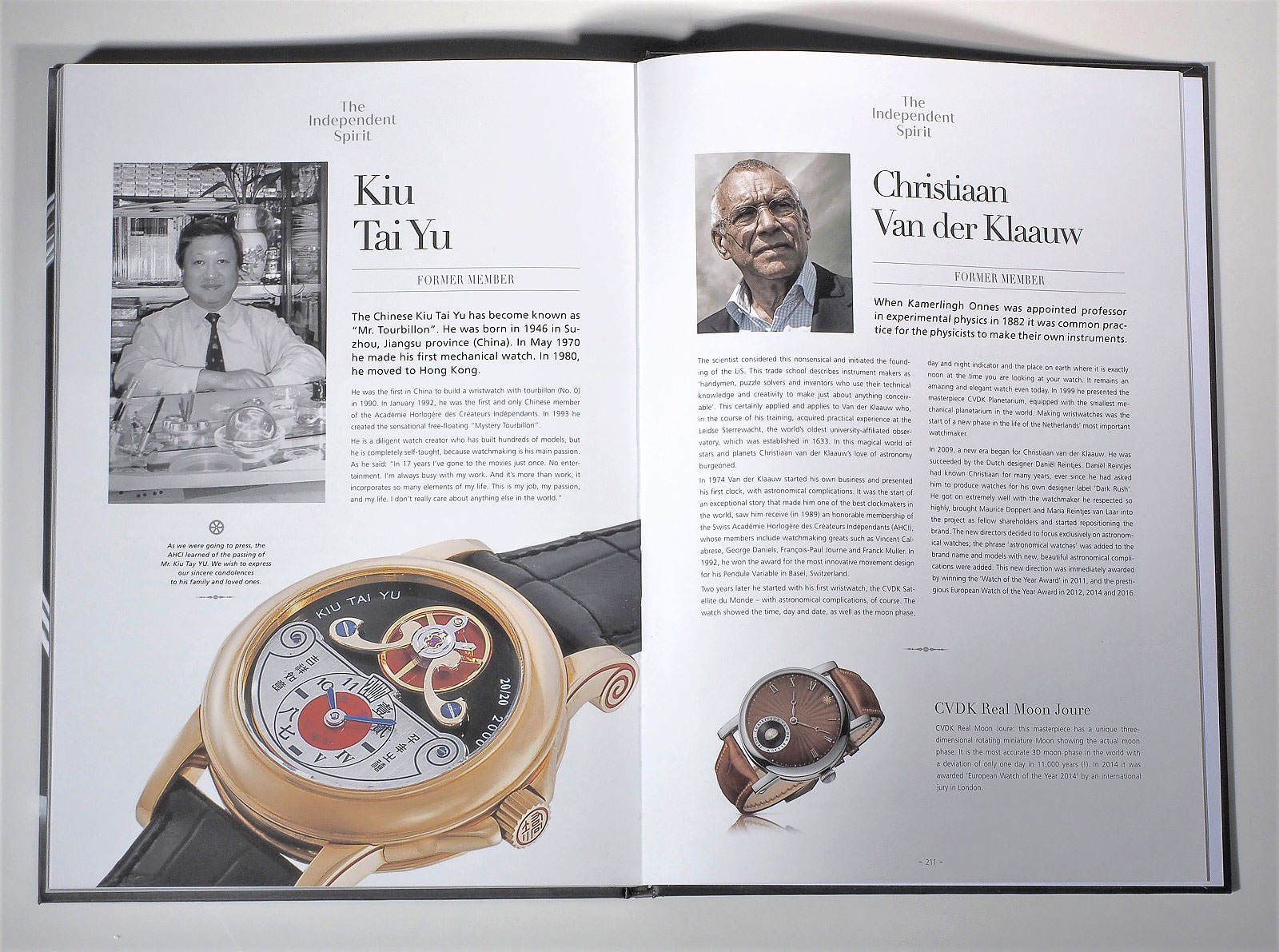

The AHCI’s 29 current members gets six pages each in The Independent Spirit, while the seven candidates for membership and 16 former members have one page each. Although Swiss watch journalist Olivier Müller is the “author” of the book, most of its content is a self-presentation by the watchmakers. In my reading, even his editing of their prose must have been restrained, since length as well as style varies wildly.

Most of the text comes from the watchmakers themselves, and lacks the technical detail that seasoned watch collectors will appreciate. At the same time, the text is somewhat chaotic in organisation and style, which means the reader needs to dig a little to glean the many interesting details and nuances about each watchmaker’s work and inclination.

Fortunately, the watchmakers within largely stick to a fact-filled style of writing that is easy to comprehend, avoiding the generic catchphrases and jargon that many big brands seem to depend on.

Having gotten wind of the production timeline for the book, I know it was a rush job. The watchmakers received notice of its publication in early October 2019, along with the deadline of November 30, 2019, in an email that read:

“Each of your profiles will be structured in the same way, with four parts:

– A short biography;

– A focus on an emblematic creation of your choice, with a few explanatory notes on why you’ve selected this piece, plus some technical and aesthetic details;

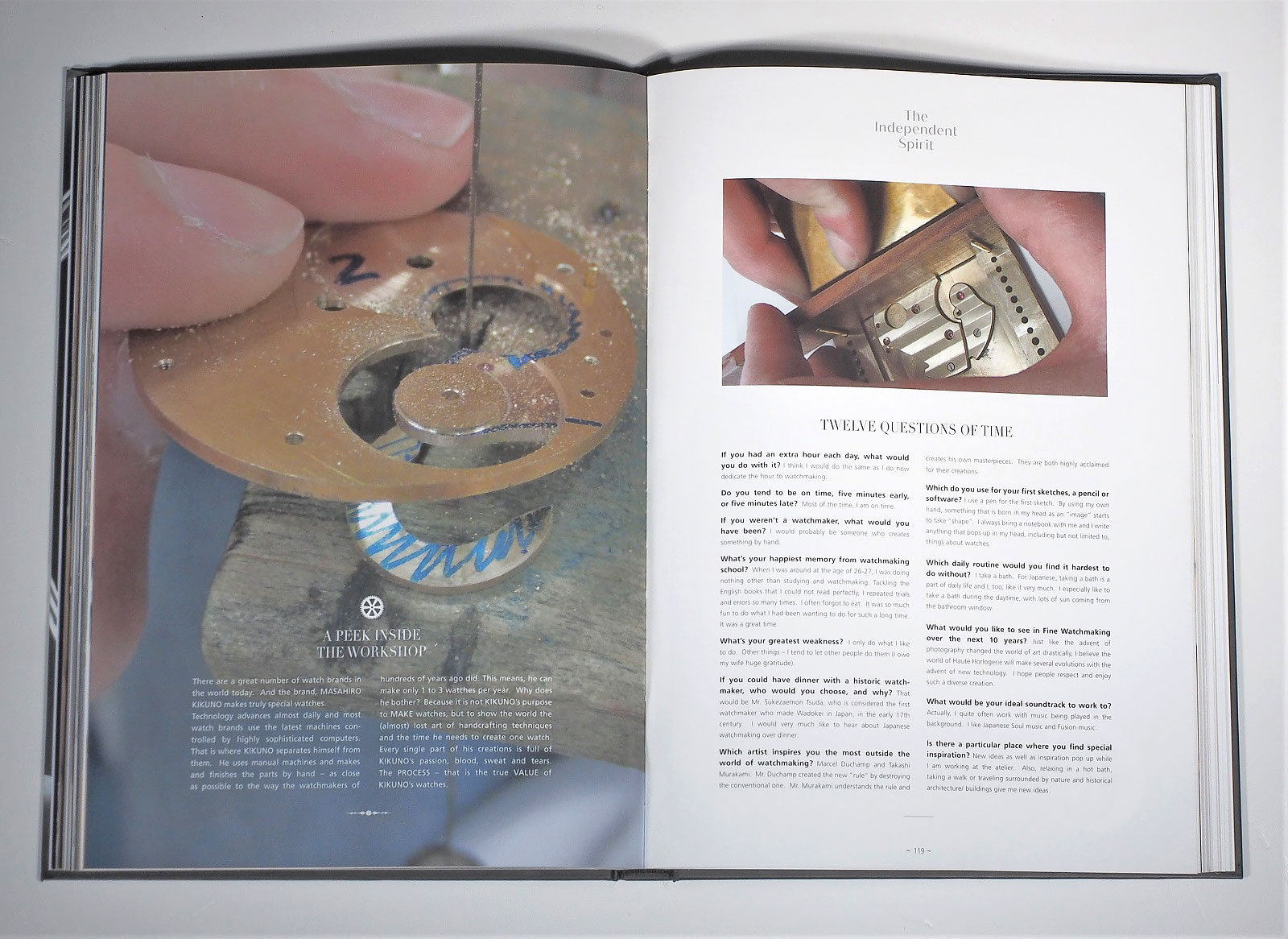

– A Peek inside your Workshop: one aspect in particular of your work (a focus on a technique that’s specific to you; a tool you couldn’t do without; a particular way of doing things; a complication that’s dear to your heart; a decorative finish you’ve created; a specific component you’d like to highlight, or any other similar aspect of your choice);

– A questionnaire: a few quick, fun, personal questions about your personality, your dreams, your ambitions, and your aspirations, with very brief answers in a couple of sentences.”

The answers to the questionnaire forms a section named “Twelve Questions of Time”, which is similar to something Peter Speake-Marin has done on his blog The Naked Watchmaker. Seeking to capture the character behind the watch, he confronts fellow watchmakers with personal questions that provide a fuller understanding the watchmaker, and perhaps even capture the person – with mixed success since not all watchmakers answered all the questions.

The questionnaire in The Independent Spirit is mostly gentle prodding of the sort found in lifestyle magazines. Messrs Haldimann and Journe were sufficiently annoyed to not answer, while others aired their opinion more subtly:

“Which daily routine would you find it hardest to do without?

Frank Jutzi: To eat.”

With the few who made a real effort to connect their work with their answers, gems can be found. An insight into the intangibles of watchmaking is made tangible by Andreas Strehler:

“… while I am working, I don’t listen to music. I need to hear what I’m doing. It’s a bit like cooking: the temperature of a pan can best be heard. In watchmaking, the sound while bevelling a bridge by hand is as important as the look and feel.”

In addition to the questionnaire, a portrait of the watchmakers are also found in their biographies, which are, as expected, mostly straightforward, professional CVs that start with watchmaking school. Embedded within the biographies is something a bit more useful to the collector: the watches each watchmaker sees as the most important ones in his own career, albeit without any illustration or description.

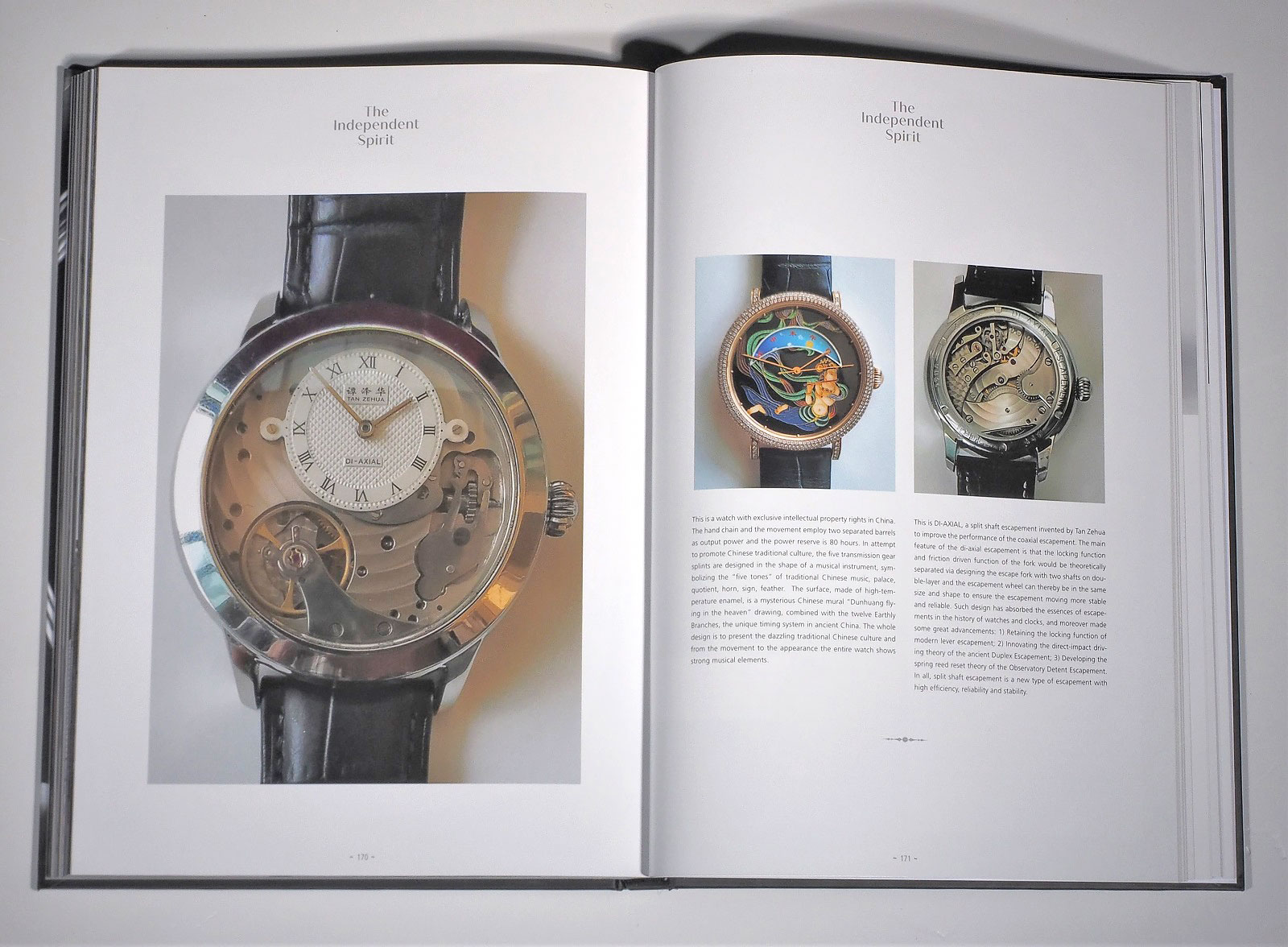

The watches that are illustrated – one to three models per watchmaker – are documented with stock photos and are typically drawn from the watchmaker’s current production. Extended captions like those found in annual watch compendium-catalogues describe the basics of each watch, no doubt to economise on space. Consequently, technical information is absent, even basic specifications like diameter or frequency. Nevertheless, the few watches showcased for each watchmaker – mostly well chosen and representative of the body of work – provide enough information about his style of watchmaking, allowing the reader to decide if further research on the watchmaker is worthwhile.

The final section, “A Peek inside the Workshop”, was left to the interpretation of the respective watchmakers – and the limits of the page. A handful make a timid attempt to explain their watchmaking philosophy, but the content is varied in its usefulness.

Beat Haldimann, generally a man of few words, supplies only a single photo. Mr Strehler offers no photos but instead narrated tour through his production facility while outlining the machines being used. And Felix Baumgartner of Urwerk explains his signature revolving satellite complication in detail. Despite the brief nature of the “peek inside”, they are the most interesting part of the book for me, often offering previously-unknown specifics of the watchmaker’s working methods.

Past and future

The Independent Spirit also covers candidates for membership and former members, living and deceased, who each have one page, which is already mostly filled with a portrait and a photo of a watch, leaving little space for substantive detail.

But a complete catalogue of former members was precluded for several reasons. Perhaps the most prominent name missing is Franck Muller, who likely could not be bothered to submit the content required. Also missing is Peter Speake-Marin, who stayed away by choice.

In terms of layout and aesthetics, the graphic designer and printer did an excellent job with The Independent Spirit. The size of the book is sufficient to show the photos well on glossy coated paper, and the portrait format chosen for the book makes it handy to read away from a table. The design is modern, without gimmicky embellishments. And despite the length of text and size of photos varying from one watchmaker to another, everything has been combined into a pleasing package.

On the other hand, a longer timeframe for putting the book together – the watchmakers in particular could have used more guidance in curating the content submitted – would have resulted in not only more coherent text and illustrations, but could also have made the book a more useful marketing tool.

For instance, personalisation and customisation is now commonly offered by startup brands in the price range below US$5,000. So the pages taken up by the questionnaire could have instead been repurposed to give the reader a better idea about the bespoke creations AHCI members can offer, or even detail their in-house production, perhaps in the form of an inquisitive, technically-oriented interview.

That said, I still found a lot of new information in the book, even though I had already seen some of the text and photos on the respective watchmakers’ websites in the past. Particularly informative were the chapters for the Chinese members of the AHCI, most of which I encountered for the first time. Their lack of an internet presence, at least in English, and the issues with communicating in person at Baselworld, had so far deprived me of the opportunity to learn more, something that this book has helped to alleviate to a degree.

And to judge the book for yourself, a sampling of its pages can be found online. The book is available by mail order direct from the AHCI for 75 Swiss francs, or about US$82. For more, visit AHCI.ch.

Correction October 29, 2020: The foreword mentioned in the second paragraph was not quoted from the book as implied in an earlier version of the article, but rather summarised.

Addition March 11, 2021: Link to the AHCI order form for the book included.

Back to top.