Commissioning Horological Art – A Watch Collector’s Experience

Watches in paint and pixel.

Lovers of horses, airplanes, yachts and cars can choose from many specialised painters if they want a piece depicting their favoured object for the walls of the home or office.

While Salvador Dalí’s surrealist “melting watch” paintings are amongst the 20th century’s best known artworks, a search for current day artists specialising in the figurative depictions of watches generates barely a handful of names, though most of whom show their works on Instagram. This is the story of my first commission, a graphic of the Voutilainen GMT-6.

High-tech capture

Particularly when wristwatches are the subject of art, I follow the original Latin definition of ars, “skills” or “craft”. Therefore, I regard flawless photography of watches as art, as with the Voutilainen 28 “Sarasamon”, captured by specialist watch photographer Guy Lucas de Peslouan.

But perfect photographic illustrations tread a thin line between art and technology. When the photographer’s skills are not at the highest level and Photoshop is heavy-handedly applied, the results are hardly suited to truly capturing a watch, yet find often a place in press releases from brands.

The art of rendering watches or movements with software is very popular with manufacturers. CGI specialist Blade Render describes its philosophy as desiring “to create images that are not only realistic, but […] also idealistic”.

A sample of such creative graphic work is Grönefeld’s 1941 Remontoire movement. The result of this technique is a photographic image without the problems of depth of field and shadows, almost impossible to accomplish when photographing the many levels of a fully assembled movement.

While I love such renders and photographs, which are a perfect illustration of watches and movements in brochures and books, I have no ambition to decorate my home like an authorised retailer’s store. What I wanted was an artistic interpretation of a watch, yet still figurative enough that there’s no second guessing of the subject.

Pen and paper to screen and stylus

As practiced by several graduates of Lycée Edgar Faure, the watchmaking school in Morteau, France, actual drawings are required to design a new watch from scratch the old fashioned way. Remy Cools, for example, conceived his tourbillon wristwatch as a pencil drawing first, before moving to a computer render, and finally starting the prototype in metal.

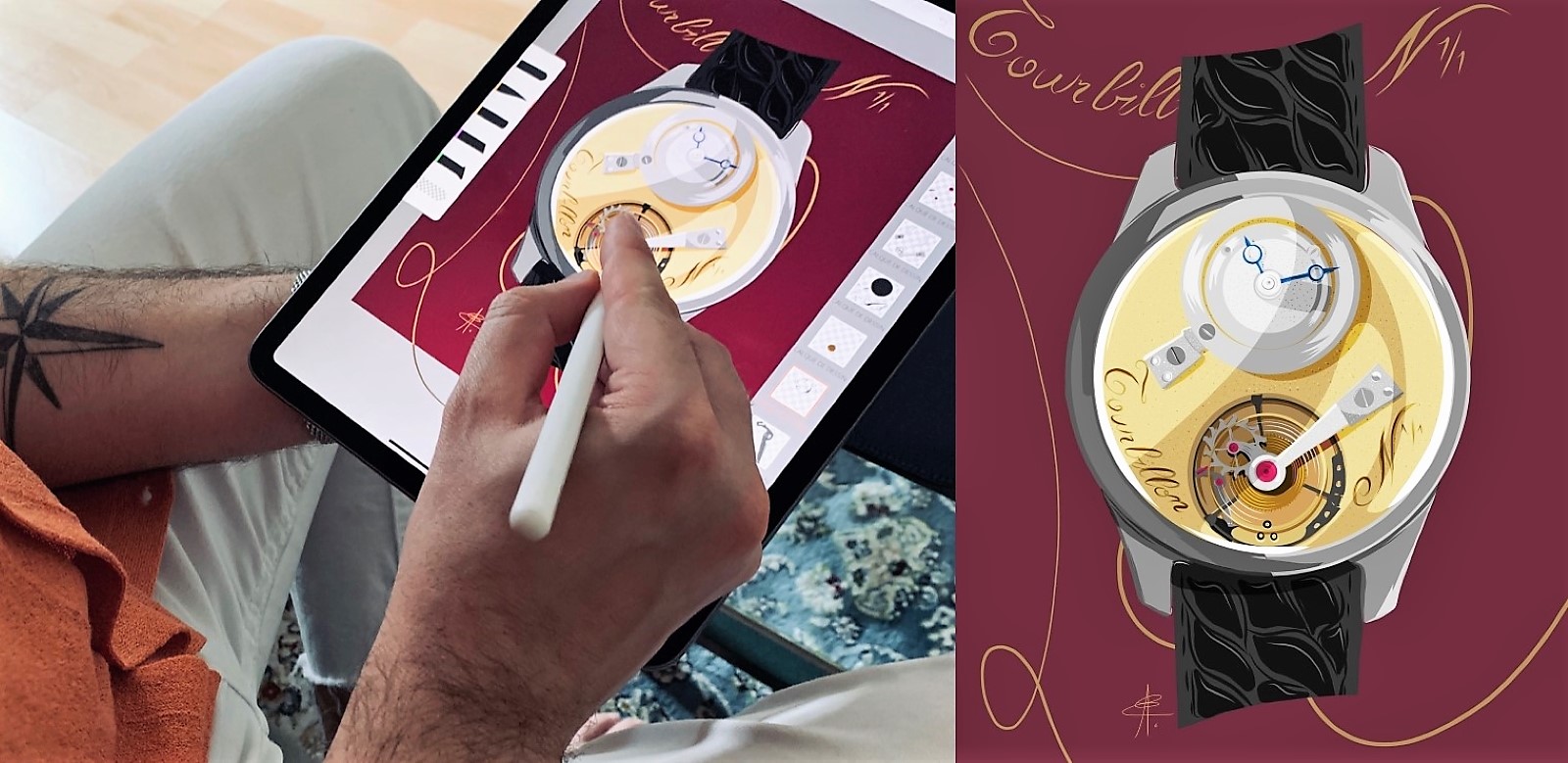

The Remy Cools tourbillon. Image – Remy Cools

Instagram watch artist Alex Eisenzammer then used Mr Cools’ finished prototype as inspiration for an illustration, abstracting the watch and presenting it as a stylised idea.

Mr Eisenzammer studied art before turning studying languages. He lives near Clermont-Ferrand in France, and relies on Instagram to promote his interest in art. He started to do portraits of watches that had left his collection to help finance the next dream acquisition.

Instead of just photographing the watches, he wanted to save their memory with more emotive means. That goal required a realistic interpretation of the watch, which led to the graphic style he still practises for commissioned work.

One of the best examples of Mr Eisenzammer’s work comes from the commissions of Martijn van der Veen, a Dutch Enicar enthusiast writing a book on the brand that will be published in winter 2019.

With custom photography and research that left no stone unturned, Mr van der Veen is also extremely demanding with the quality of illustrations in his book. The subdued style chosen for the custom graphics, all done by Mr Eisenzammer, add further visual interest to the book, and matches my own taste of what horological art should be.

When I asked Mr Eisenzammer what style he prefers personally, he responded that he enjoys adding a thematic background relating to the watch in the painting. The two samples below, featuring Seiko and Omega respectively, need no further explanation of the themes.

Two recently created graphics representing independent watchmaking are particularly impressive. The bold design of watches like the De Bethune DB 28 Tourbillon and the MB&F LM Perpetual are especially suitable for Mr Eisenzammer’s style of drawing. The graphic of the De Bethune reminded me of what a superb combination of modern design and traditional watchmaking this brand offers.

Image – Alex Eisenzammer/@watchoniste

The Voutilainen commission

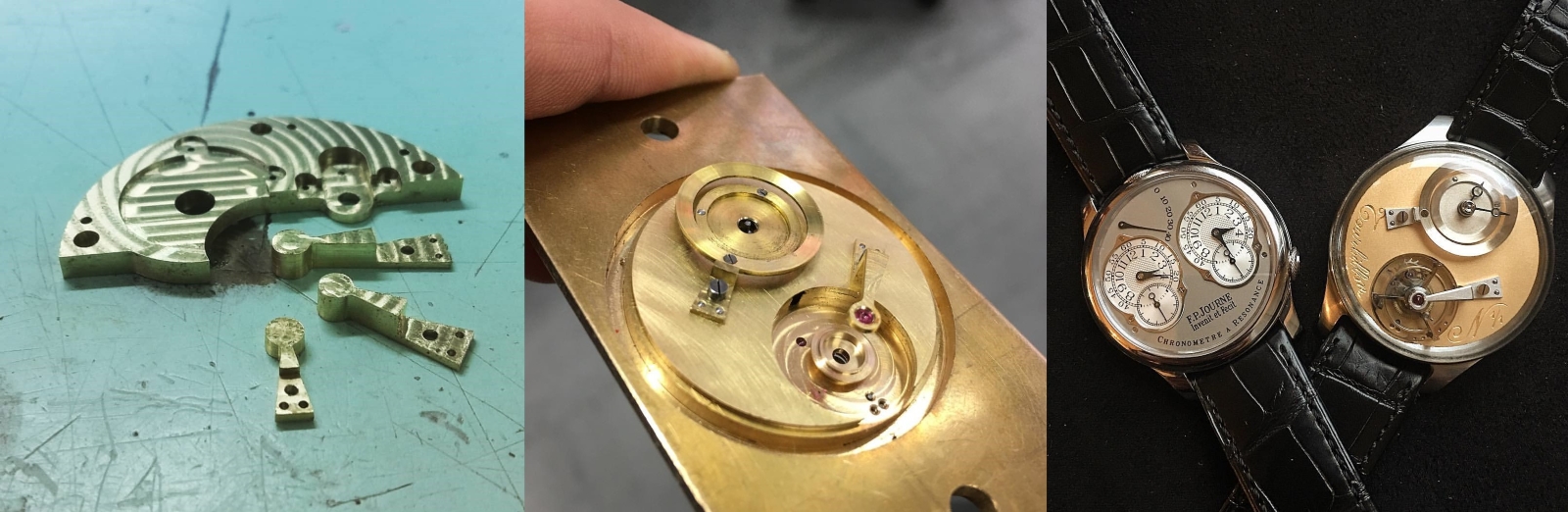

When I proposed a painting of the Voutilainen GMT-6, I was keen to integrate the technical features of the watch into the background. Prominent features of the Vingt-8 movement are the oversized balance wheel and patented double wheel escapement.

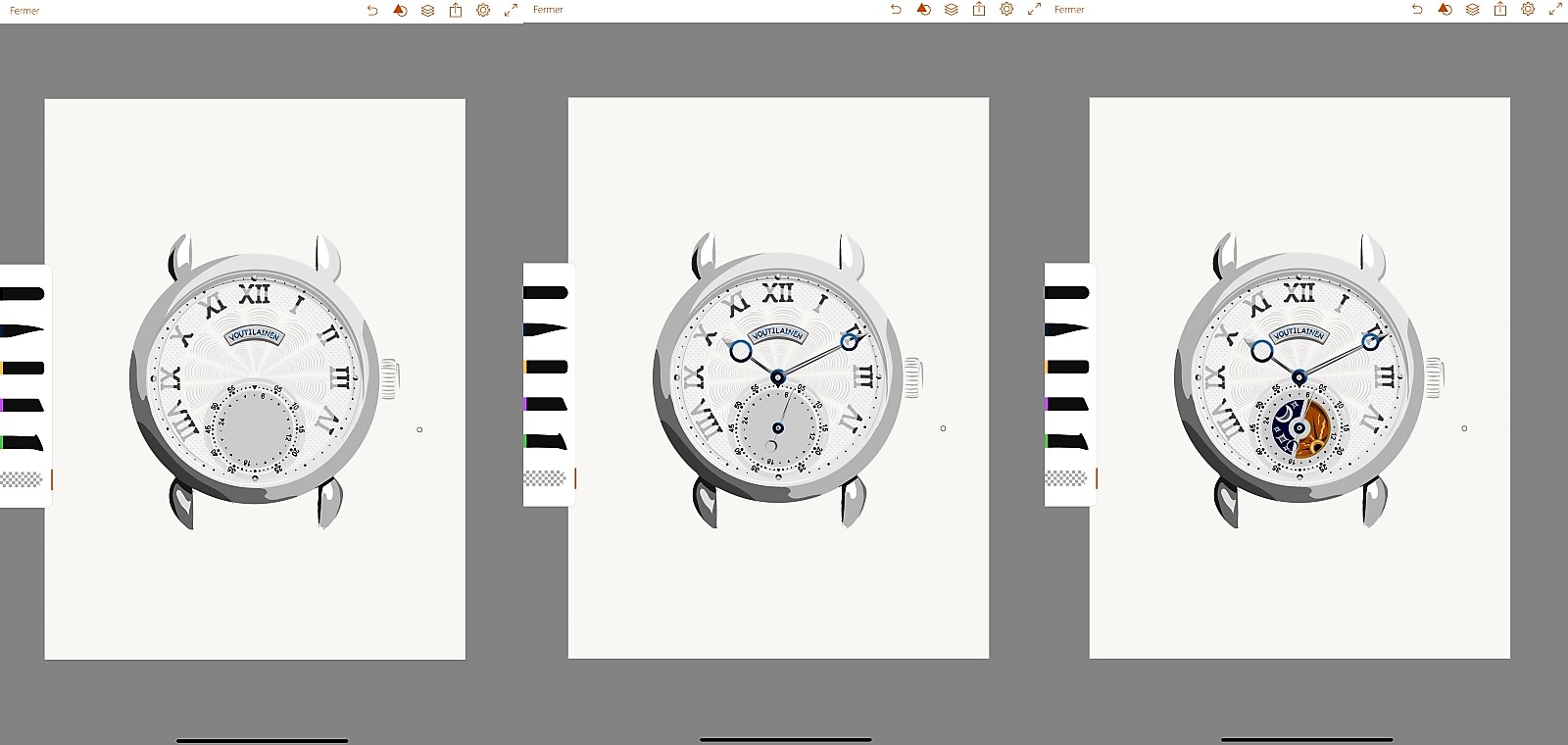

So I provided a couple of photos of the watch, which Mr Eisenzammer requires in order to begin any commission. And I also combined the proposed background elements the old school way – with photocopies, a pair of scissors, and glue (in extreme left image below).

The first proposal (centre) by Mr Eisenzammer didn’t convince me; I thought the illustrations of movement parts overwhelmed the portrait, particularly due to the completely different styles of the illustrations. Leaving out one of the elements (extreme right) also did not work.

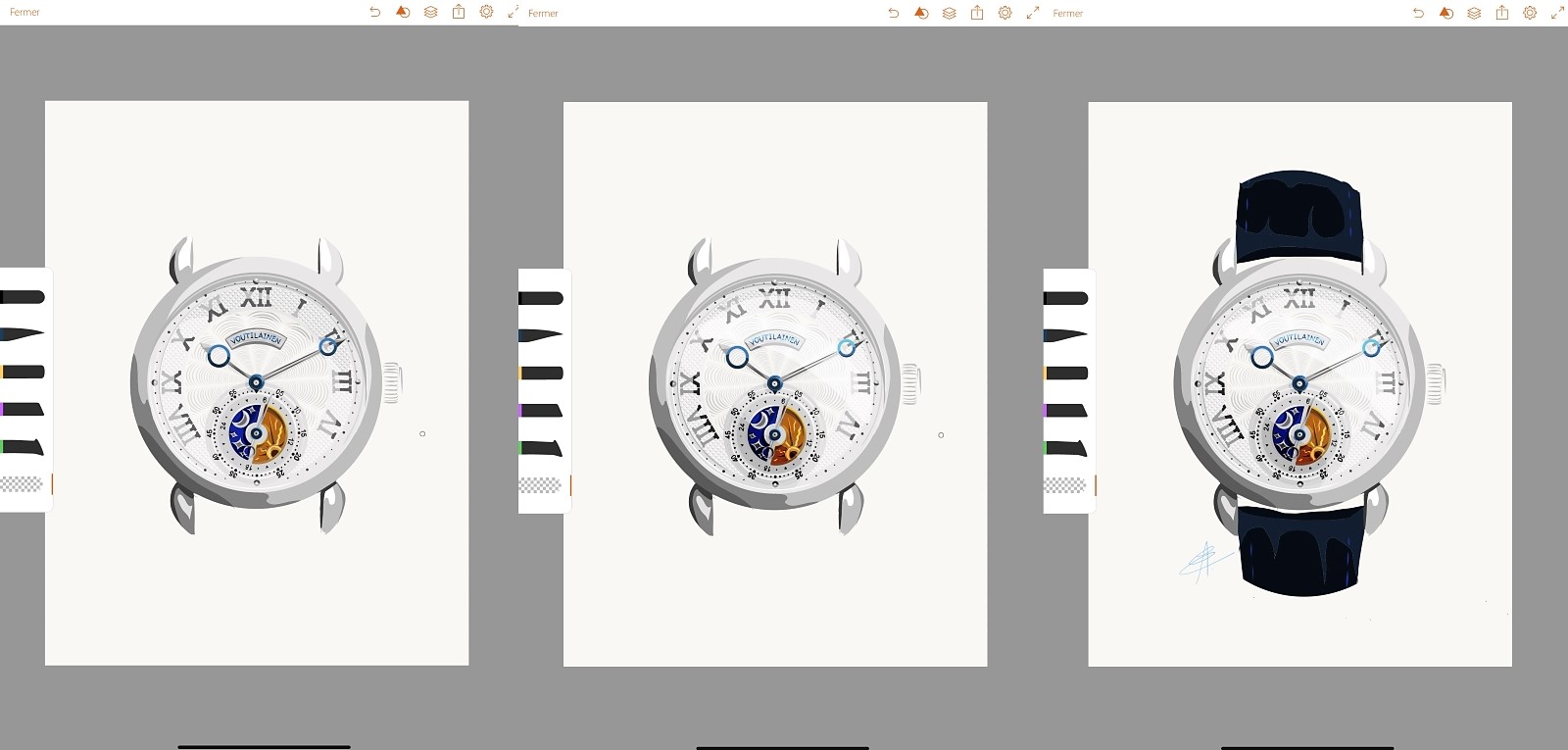

Softening the drawing of the balance wheel by replacing black lines with dark blue ones and adding the graphics of the guilloche pattern led then to the final version of the illustration.

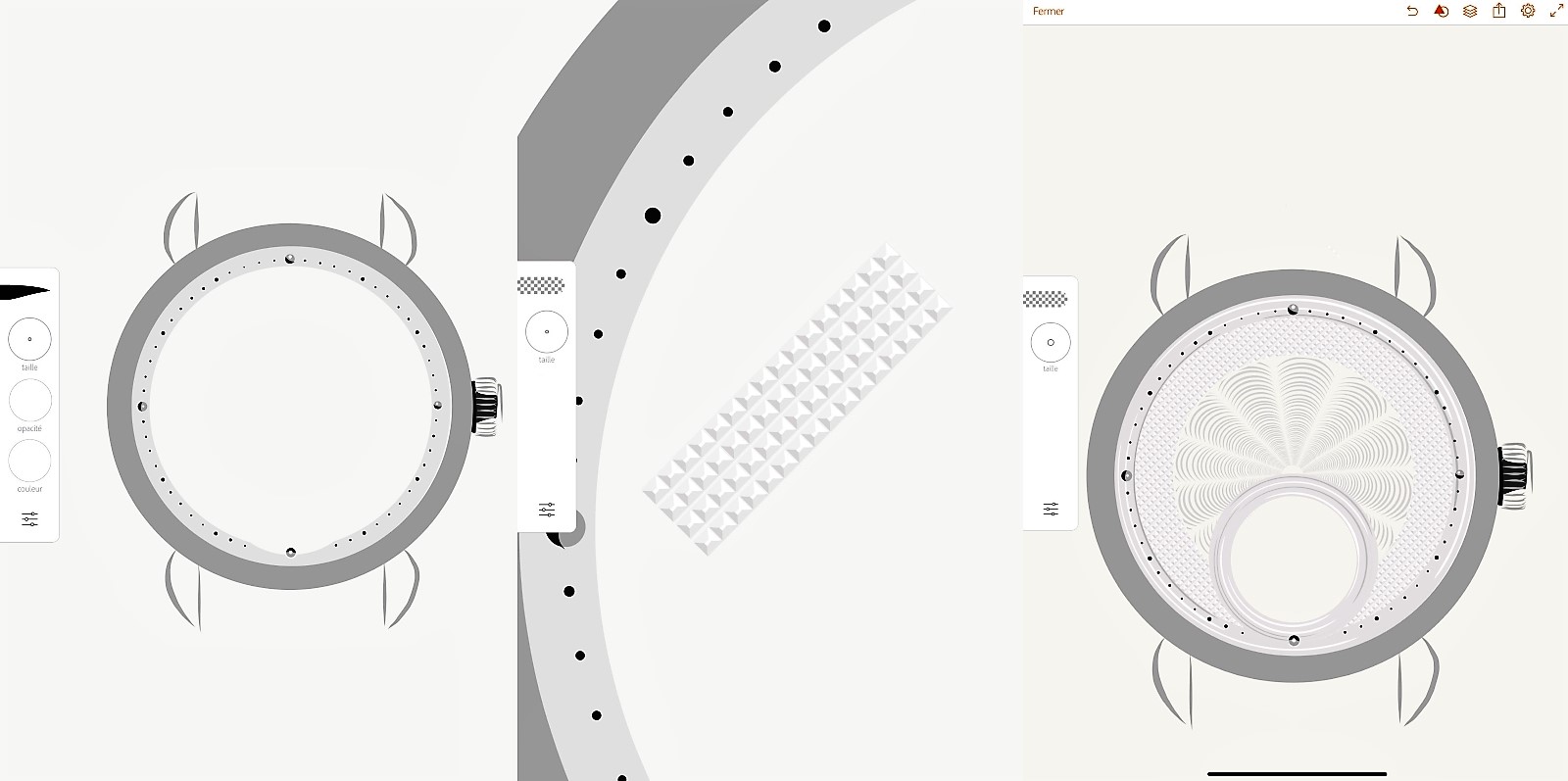

Mr Eisenzammer’s work is not a literal translation of a photography into a graphic illustration. He starts his work on an iPad Pro, and uses a stylus to create the image. It begins with the watch case based on a template, followed by the creation of the texture on the various parts of the dial, and finally the dial details are added.

One by one, details like numerals, hands and the day and night disk, are then added on top of the basic texture of the dial.

With all features of the dial in place, the play of light and shadows have to add interest. First lights and shadows cast by the case are shaded on part of the dial, followed by shadows and reflections on case, crystal and hands. Finally, the strap is installed. This leaves the background and its details to complete the graphic illustration.

Mr Eisenzammer is @watchoniste on Instagram. His posts are frequent because the commissions take only a couple of days to complete after he receives the photos supplied by the client. The finished graphic is delivered as a PNG file. The Voutilainen portrait arrived in a size of 3072×4096 pixels, which allows quality printing at 300dpi up to a size of about 26cm by 35cm.

With the Adobe Draw program used to create the graphic, a maximum paper size of about A1 for 300dpi printing is technically possible, but due to occasional software problems in saving the image file, the size I received is the preferred maximum at the moment.

I found it convenient to get a data file of the artwork instead of a physical print, as it allows me to choose specific archival paper for the print. The price for commissions start at around €100, going up to about €250, depending on how intricate the details have to be.

More watch artists

Artwork created the traditional way – with pencils on art paper or acrylics on canvas – typically start at about US$5,000 for mid-sized works. Larger formats can be around $20,000, although some of these artists offer also prints of existing watch portraits at more affordable prices. Examples of such artists include Julie Kraulis, who works with pencil on paper, and Nicholas W. Starr, whose works are acrylics on canvas.

Another artist began his career as an illustrator covering fashion shows, and later developed a method of creating portraits, in watercolour on 600gsm paper, but executed quickly enough that he can offer original artwork at print prices. Matthew Miller, who goes by @sunflowerman.watches on Instagram, charges US$250 for an A5 size work, with rates rising to US$1,500 for a A3 painting.

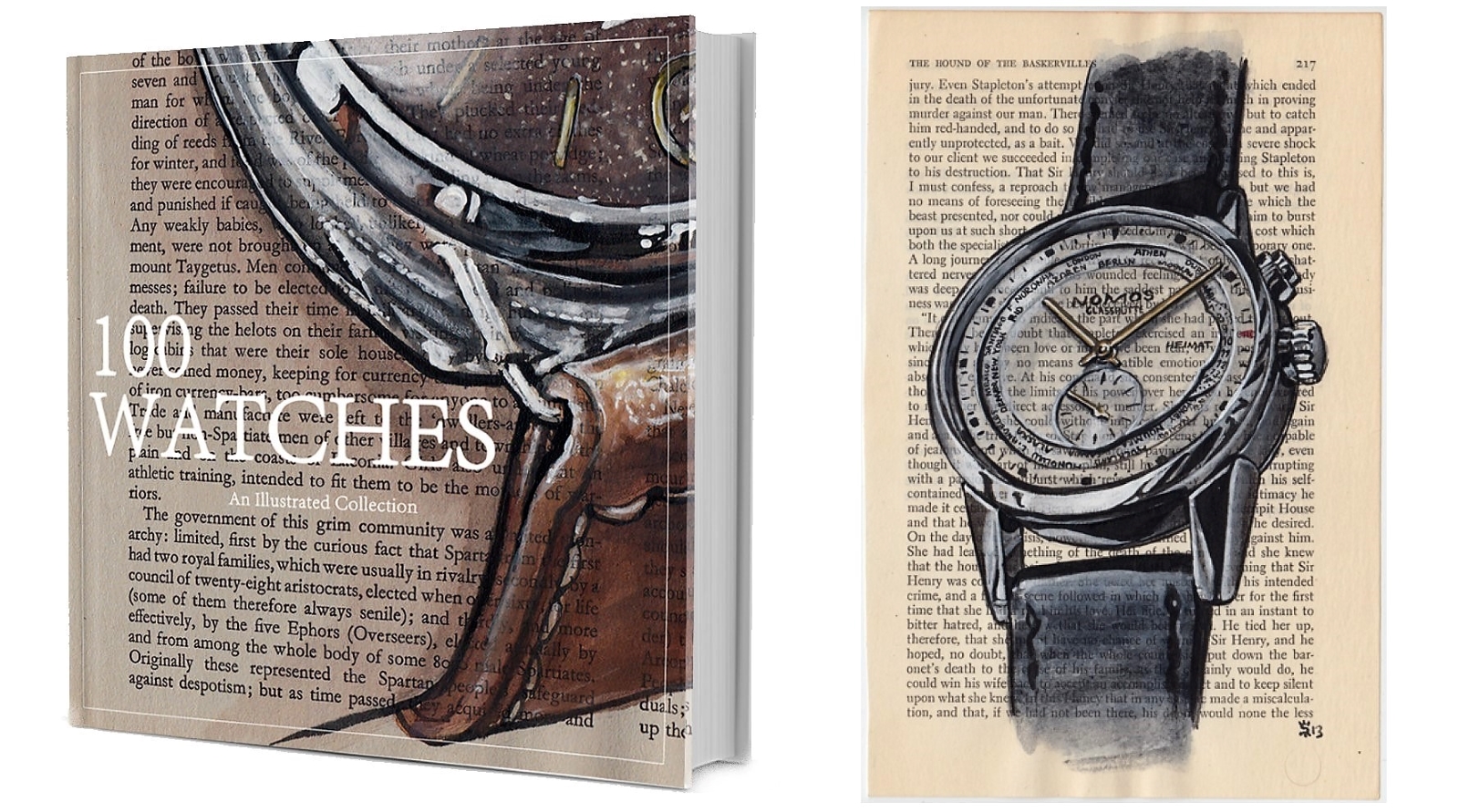

Mr Miller is an American illustrator who was drawing menswear before watch photos on Instagram aroused his interest, although he didn’t wear a watch himself. Polling enthusiasts on Instagram as to what watches they would like to see on canvas, he began a project of painting 100 watches in 100 days.

The resulting watch portraits were done on pages taken from books, with the printed text becoming the background. Reproductions of the portraits were bound into a hardback volume that is still available on Amazon.

Mr Miller practises his art in three distinct styles. His commissioned work is what he calls “studio art”.

According to Mr Miller, “in the studio is where the details are expressed. What I love about creating highly detailed watch illustrations in watercolor is the paradox. Watercolors are known for their ill temperament, their inability to follow direction, their wild nature. This stands in direct contrast to the rigidity and the precision of watchmaking. Fine watches are exacting and measured to the finite degree.”

Like Mr Eisenzammer, Mr Miller seems to enjoy particularly “editorial art”, which he describes as “watch illustrations [offering] a chance to move beyond the portrait of the watch and into the life and adventure of the watch. How does a watch change our perceptions of the world? How can we see a watch differently?” Such stories are told in the background of the watch portraits.

The third pillar of Matthew Miller’s artistic work is “live art”. This is more of a “freehand” approach and a less detailed depiction; it’s the style he uses for smaller commissions. Usually, these portraits are painted live at events like Baselworld or boutique openings.

He expresses his appreciation of such live painting sessions: “[I] love to be able to work quickly and maintain the attention of an audience. In about 20-40 minutes I can complete a full watch illustration from drawing to color. This is true of the Voutilainen [below]. Often in this process I will begin with a very simple line drawing in graphite. It will complete the the general shape of the case as well mark where lugs, indices and hands will be detailed. Then I continue with a black pen, sometimes Sharpie or Copic or Faber-Castell. To finish, I will end with marker or watercolor. It is dependent on the circumstance. Watercolor has more history, more culture, more gravitas.”

Art and soul

In watchmaking, “authentic” is often misused for marketing purposes, applied as liberally as “hand-made”.

During the panel discussion on independent watchmaking that took place in May at Phillips auctioneers in Geneva, Stephen Forsey emphasised how marketing alone cannot create an authentic and interesting watch. Rather, the necessary ingredient is a watchmaker who wants “to tell a story”.

That holds true for art. Scholars like Dennis Dutton, author of Authenticity of Art: The Oxford Handbook of Aesthetics, refers to “expressive authenticity”: the object’s character has to be “a true expression of an individual’s… values and beliefs”.

Messrs Eisenzammer and Miller create their watch portraits in a style they have developed to please themselves, recording watches for personal projects. I appreciate the resulting distinctive artworks, which do not, and need not, match my own preferred style down to the smallest detail.

For me, a most important quality of the work is to express the personality of its creator. As it is with watches, I want to see a bit of the creator’s soul.

European collector Björn Meijer focuses on world time and multi-time zone clocks and watches, but he is particularly fond of independent watchmakers.

Back to top.