The Fake Rivalry That Created the World’s Most Expensive Timepiece

The myth of Henry Graves Jr. vs James Ward Packard.

The story of two American magnates – Henry Graves Jr. and James Ward Packard – in the early 20th century, locked in a desperate contest to acquire the most complicated — and expensive — watch will be familiar to those acquainted with the brand mythology of the Geneva watchmakers, Patek Philippe.

The spending contest, the clash of egos, the subterfuge are the inevitable ingredients in a story of rival collectors. To add to the clichés, the ultimate prize, the most complicated portable timepiece in the world, has brought misfortune to its owners and is assuredly as cursed as the jewel stolen from a vindictive idol.

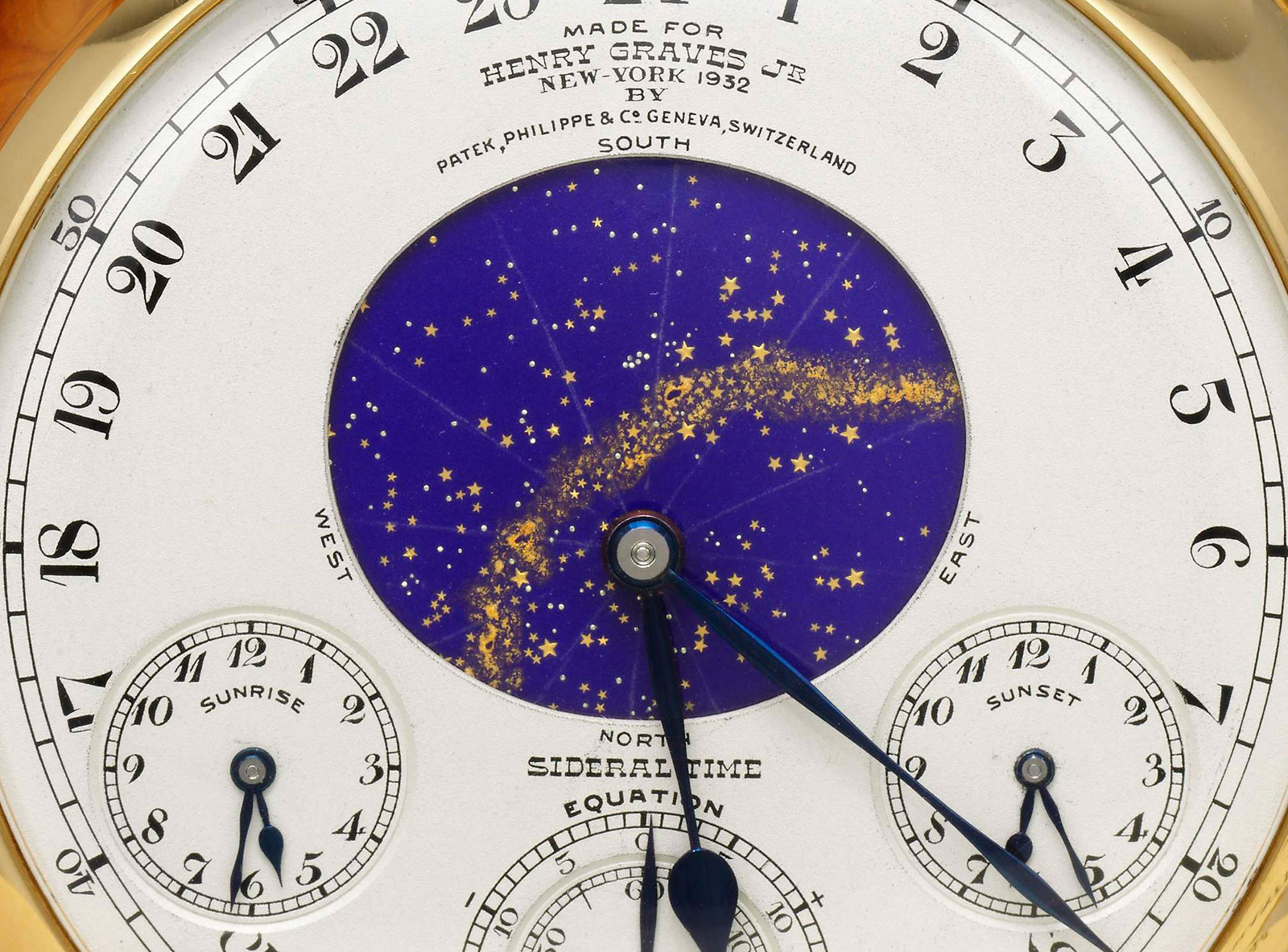

The tale of the arms race between staggeringly rich Henry Graves Jr. and James Ward Packard, creator of America’s first luxury car, soon bore fruit. Told to a reporter ahead of the Sotheby’s auction of the Graves watch, it persuaded Saud bin Mohammed Al-Thani to pay a record-breaking US$11 million at Sotheby’s in 1999 for the victorious supercomplication completed for Graves in 1932.

The sheikh, a member of Qatar’s ruling family and onetime minister of culture, is fondly remembered by dealers and auctioneers for his prolific spending on art and gadgets before forfeiting his wealth fighting corruption charges. The sheikh died unexpectedly in 2014, two days before Sotheby’s again sold his Graves watch for US$24 million, making it the most expensive timepiece and earning it the title of the Mona Lisa of watchmaking.

The much-embellished Graves-Packard duel even became the subject of a book, A Grand Complication — The Race to Build the World’s Most Legendary Watch, by Stacy Perman, published in 2013.

The Patek Philippe Henry Graves Supercomplication that sold for US$24m

Yet this alleged rivalry between two rich men to possess the ultimate timepiece is a complete fabrication. Asked to comment on the book, Alan Banbery, a former director of Patek Philippe, and architect of the company’s post-quartz resurgence, admitted to being the source of the Packard-Graves rivalry story.

He floated it in the early 1990s to promote his company’s lucrative competence in highly expensive complications, recently incarnated by the Calibre 89. In 1999 he raised it in a newspaper interview ahead of the sale of the Graves watch.

There is no evidence or even indication that Packard and Graves ever met; they acquired different types of watches independently and moved in distinct social circles. Graves was five years younger than Packard and outlived him by 25 years.

James Ward Packard was a hands-on engineer. He made a fortune in light bulbs and another in automobiles, for which he invented the steering wheel.

James Ward Packard, pictured in one of his early automobiles, c. 1900. Credit Lehigh University Photograph Collection

Henry Graves Jr was a scion of America’s old-money aristocracy. He inherited a banking fortune and made another in real estate, railways and by cornering cement. He pursued a life of active leisure in a style suited to a man of cultivated tastes.

His Fifth Avenue apartment and the country mansions in Irvington and Saranac NY, where he raced his motorboat, were lavishly decorated with furnishings, works of art and silver, bearing the Graves crest and motto Esse quam videre — reality rather than illusion. In winter, the family migrated to Charleston, where Graves, a keen horseman, frequented the Yeamans Hall country club. The few published photographs of him show a gentleman who evidently employed a first-class valet.

Henry Graves Jr. Credit Sotheby’s

Graves would have regarded Packard, if he were indeed aware of him, as a mere mechanic.

Their different approaches to collecting make any personal rivalry even more unlikely. Packard was one of those kids who take apart the family clocks and fix their friends’ watches. As a mechanical engineer, he had a professional appreciation of watch mechanics and sought out its possibilities in an eclectic variety of chiming and astronomical timepieces, a ring watch, one for the top of his cane and another that played his favourite lullaby. He mainly bought chiming watches with astronomical complications from Patek Philippe, and precision watches from English makers.

Graves simply hoarded the best of anything: the rarest coins, the most priceless Chinese porcelain, the prettiest paperweights, artworks of royal European provenance. For him the best watches were the most accurate, so he snapped up the winners of the Swiss observatory competitions, many of them from Patek Philippe and some from Vacheron Constantin.

The “race to build the most legendary watch” between the two men is furthermore contradicted by their collecting history. It must be remembered that the dates of their custom-made watches (the Packard 1916, the Graves 1926, the Packard 1927 and the Graves 1932) are those of their completion, not their order. They took several years to build.

Packard ordered his most complicated watch from Patek Philippe in around 1910 and it was delivered in 1916. Graves only got interested in complicated watches in 1919, when he was 51 years old, but none of those he ordered from Patek Philippe were specified to outrank the 15 complications of the Packard 1916 watch.

By the time his watches were delivered from the mid 1920s, Packard, in hospital with a brain tumour, was no longer ordering watches. His last and most elegant watch, with 10 complications and a star chart was delivered to his hospital bed in 1927.

The Packard astronomical pocket watch by Patek Philippe delivered in 1927

The Graves grand complication pocket watch delivered in 1926, with the his family’s crest on the back

It was only after Packard’s death in 1928 that Graves arrived in Geneva to give Patek Philippe the go-ahead to produce the 24-complication watch that had been under development for three years. If Graves were competing in the complication stakes, it would not be against any of Packard’s watches. The watch to beat was the 20-complication Leroy 01, completed in 1904 for the stupendously rich Portuguese mystic, Dr Antonio Augusto Carvalho Monteiro.

Furthermore, Graves was not the kind who would stoop to compete. If you acquire the best, you don’t need to.

The Leroy 01 grand complication pocket watch. Credit Musée du Temps Besançon

It’s always a pity to let facts get in the way of a good story, but the clever marketing myth has served its purpose of supporting Patek Philippe’s strategy, not to sell more watches, but to increase their price. In the global competition for status, the message of the Graves-Packard rivalry is embedded: the money spent on a Patek Philippe buys a guarantee that you outclass your rivals. In the top price range, the company is secure in its reputation as the maker of the most expensive complicated watches.

However, collectors’ motivations change. Today they can be compelled to buy Patek Philippe’s minute-repeaters on the grounds they have been individually listened to, personally, by the owner of the company.

Stories ain’t what they used to be.

Alan Downing worked as a news journalist in Africa and in Europe before being drawn into the world of luxury watchmaking at the start of the post-quartz revival. Since then he has written for and about the Swiss watch industry, gaining a privileged insight into a fascinating artistic, economic and industrial culture. Some readers might remember the Watchbore character he created on the Timezone watch forum.

Back to top.