Explaining the Making of a Bona Fide In-House Movement at Glashütte Original

We explain how an in-house movement - a real in-house movement - is made from start to finish at the vertically integrated manufactory of Glashütte Original.

Glashütte Original is, in some ways, the original watchmaker in the eponymous German town that is also home to peers like A. Lange & Söhne and Nomos. And Glashütte Original is arguably the most vertically integrated watchmaker in the town, a virtue that’s a consequence of historical troubles. We recently visited the Glashütte Original manufactory to see it for ourselves, and now we explain how the movements are made.

From the ashes of war

Unlike many of its peers, Glashütte Original is vertically integrated because of its history, rather than the desire to boast of in-house movements. The origins of the company begin with the ruins of the Second World War, with much of the region having been destroyed by the Allies. The town of Glashütte is just 40 minutes away from Dresden, the gorgeous historical capital of Saxony that was reduced to rubble in 1945. When the war finally ended, Glashütte ended up on the Soviet side of Germany and all its watchmaking companies, ranging from Lange to Mühle, were merged to form state-owned VEB Glashütter Uhrenbetriebe (GUB) in 1950.

GUB continued to make watches and clocks (and even marine chronometers) in the succeeding decades, focusing on basic timepieces rather the fine watches Glashütte was known for before the war. Nonetheless GUB watches like the self-winding Spezimatic sold in large numbers – several million were made by the time the Wall came down – with many being exported to West Germany.

The upside of being on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain was that GUB had to be self-sufficient, laying the foundations of the modern day Glashütte Original manufactory. So when capitalism came to the town when the Berlin Wall fell in 1990, GUB was transformed into a private watchmaking enterprise that made all its movements in-house at a time when only a handful of watchmakers anywhere were doing so. The robust but barely decorated GUB calibres were reengineered and dressed up, becoming the first of dozens of in-house movements Glashütte Original has introduced since reunification.

Manufacturing a watch movement starts with raw materials, like sheets of brass and tubes of steel, which are then turned into components like screws and plates. Those components then need to be finished with decoration, plating and engraving. In between each of those steps quality control takes place, each part is measured or inspected to ensure it is up to scratch. And finally everything is put together into a movement. This process is the same at every brand, except that for most watch brands the intermediate steps are subcontracted out. Glashütte Original, on the other hand, does almost everything itself. Here is what goes into making an in-house movement, summarised into eight digestible steps.

1. Making parts to make parts

Some 95 percent of every Glashütte Original mechanical movement is made in-house, with only the hairspring, mainspring, Incabloc shock absorber and jewels coming from suppliers (which are all sister companies in the Swatch Group, the watchmaking conglomerate that acquired Glashütte Original in 2000). Vertical integration at Glashütte Original begins with the toolmaking department that makes key parts for manufacturing movement components. Too specialised to be bought off the stuff, such parts include drill bits and movement holders.

2. Multipurpose and multi-axis

Computer numerical control (CNC) machines describe automated machine tools like mills and lathes that make parts via reductive manufacturing techniques – basically cutting roughly shaped stuff into more precisely shaped stuff – that are standard throughout watchmaking. Several types of CNC machines are commonly used in watch factories; in fact many manufactures have the same models of machines from the same manufacturers, like Fanuc of Japan for instance. Being vertically integrated, Glashütte Original possesses almost all types of CNC machines.

CNC milling machines, for instance, are used to cut out larger parts, forming a component by removing material from a blank that’s usually brass, an alloy of copper and zinc. The signature three-quarter plate found in all Glashütte Original movements is made this way, as is the oscillating weight in self-winding calibres. These machines are also responsible for the engraved lettering on the plate, including “Made in Germany”, but not the engraving on the balance cock, which is hand applied.

Minuscule parts can also be made with CNC machines, albeit of a different type. A more specialised machine, the rotary bar feeder, is a lathe that automatically feeds a bar of material into a cutter that forms small round parts like wheels and screws.

Rotary bar feeders

3. Let sparks fly

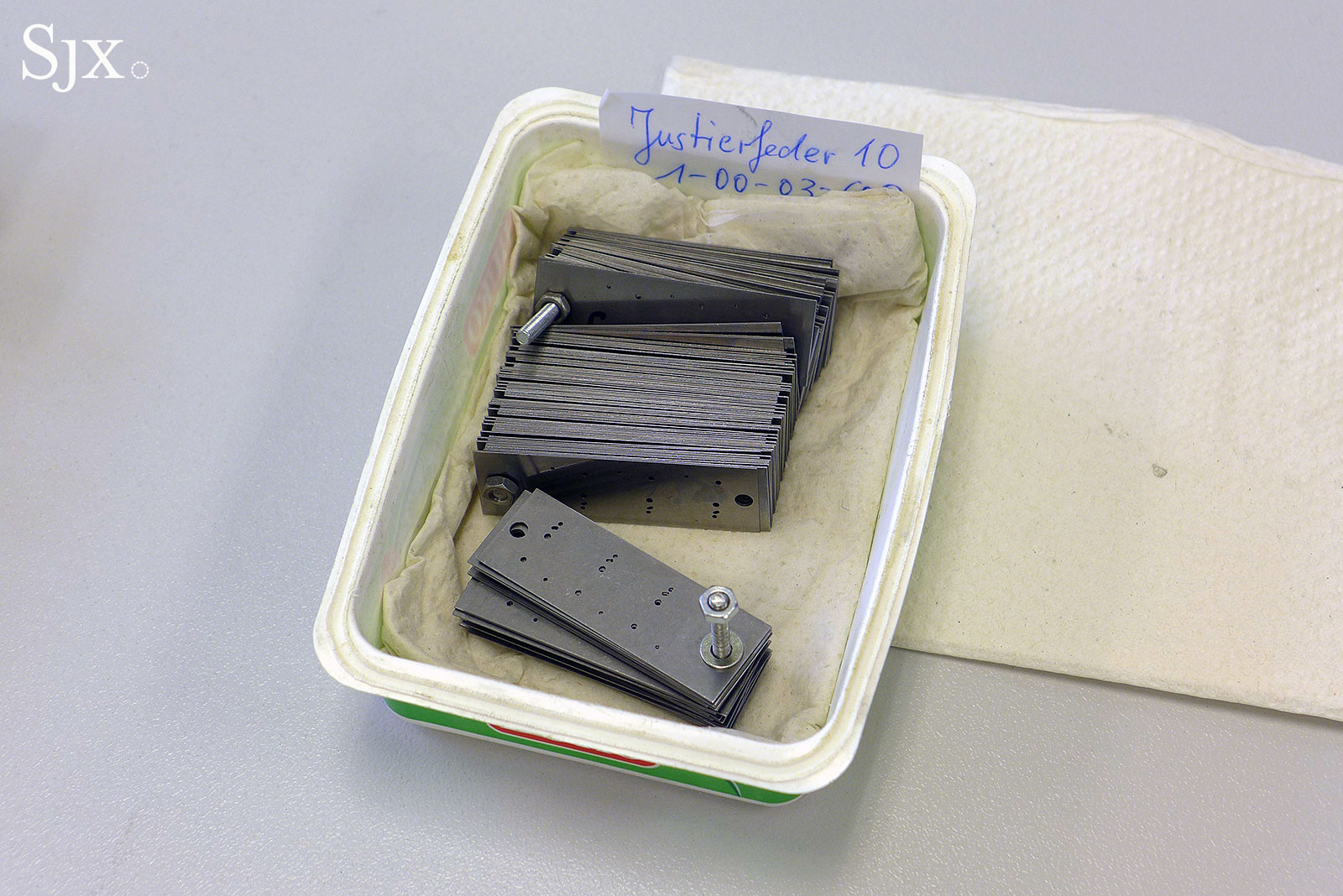

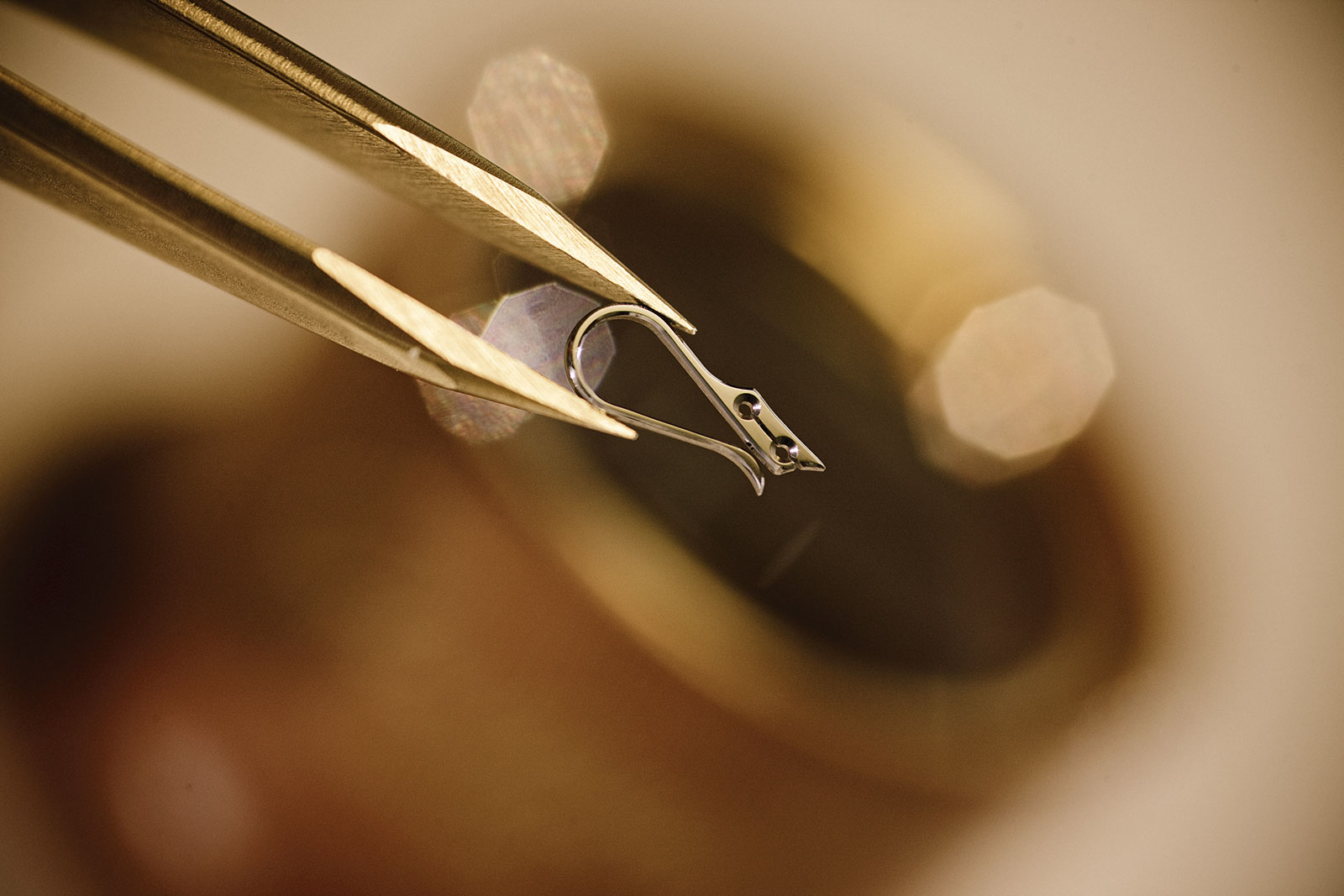

Other small parts are made made either via electrical discharge machining (EDM), also known as spark or wire erosion. Typically used for smaller, thin parts like springs and swan neck regulators, wire erosion utilises a wire carrying electric current used to cut a stack of metal plates, forming identical components out of each plate. Usually the metal plates are stacked 10 to 15 high, with brass, steel and beryllium (a metal used for make the balance wheel) being the most common alloys used. Once complete, the parts can be popped out of the plates.

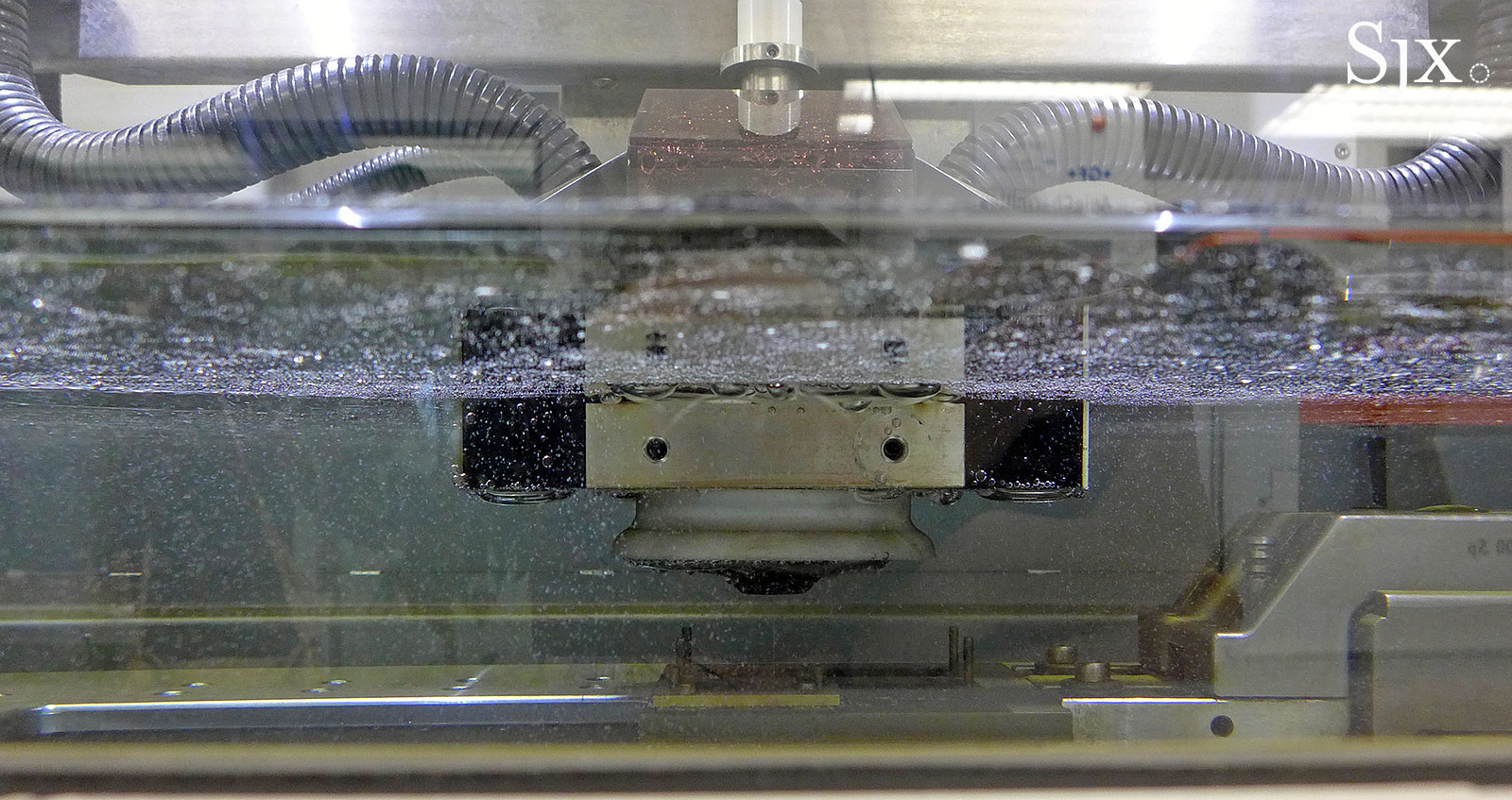

A Swiss-made wire erosion machine

Stacked blanks of steel for wire erosion

Wire erosion taking place in a tank of deionised water

4. Finishing

Finishing encompasses various techniques – many of which are done by hand – to decorate the parts of the movement for aesthetic and functional purposes. Finishing is the step in production that conceivably involves the highest level of manual labour and craftsmanship, which is why watch enthusiasts hold it dear. Notably, the most labour intensive finishing technique in a Glashütte Original movement is engraving the balance cock, a signature feature of watches made in Glashütte.

Other finishing techniques employed to decorate the movement range from the manually to the mechanically applied. Covering the largest surfaces of the movement, the most obvious finishing technique is striping, commonly known as Cotes de Geneve on Swiss watches, a series of fine scratches applied in waves using a spinning disc. This process is automated and done by a CNC machine, explaining the pleasing uniforming of the stripes.

The more subtle art of perlage, however, is done by hand, though most of the surfaces so decorated are invisible. Perlage refers to tiny, tightly spaced circles resembling pearls that are ground onto the surface, usually the base plate of the movement. The pearls are applied one by one, with the craftsman or woman (many of those doing finishing are women) pulling down a lever that presses a small spinning disc against the surface of the base plate. Too much pressure on the lever and the pearl will be coarse and deep, while too little and the result is too faint; it has to be just right.

Applying perlage

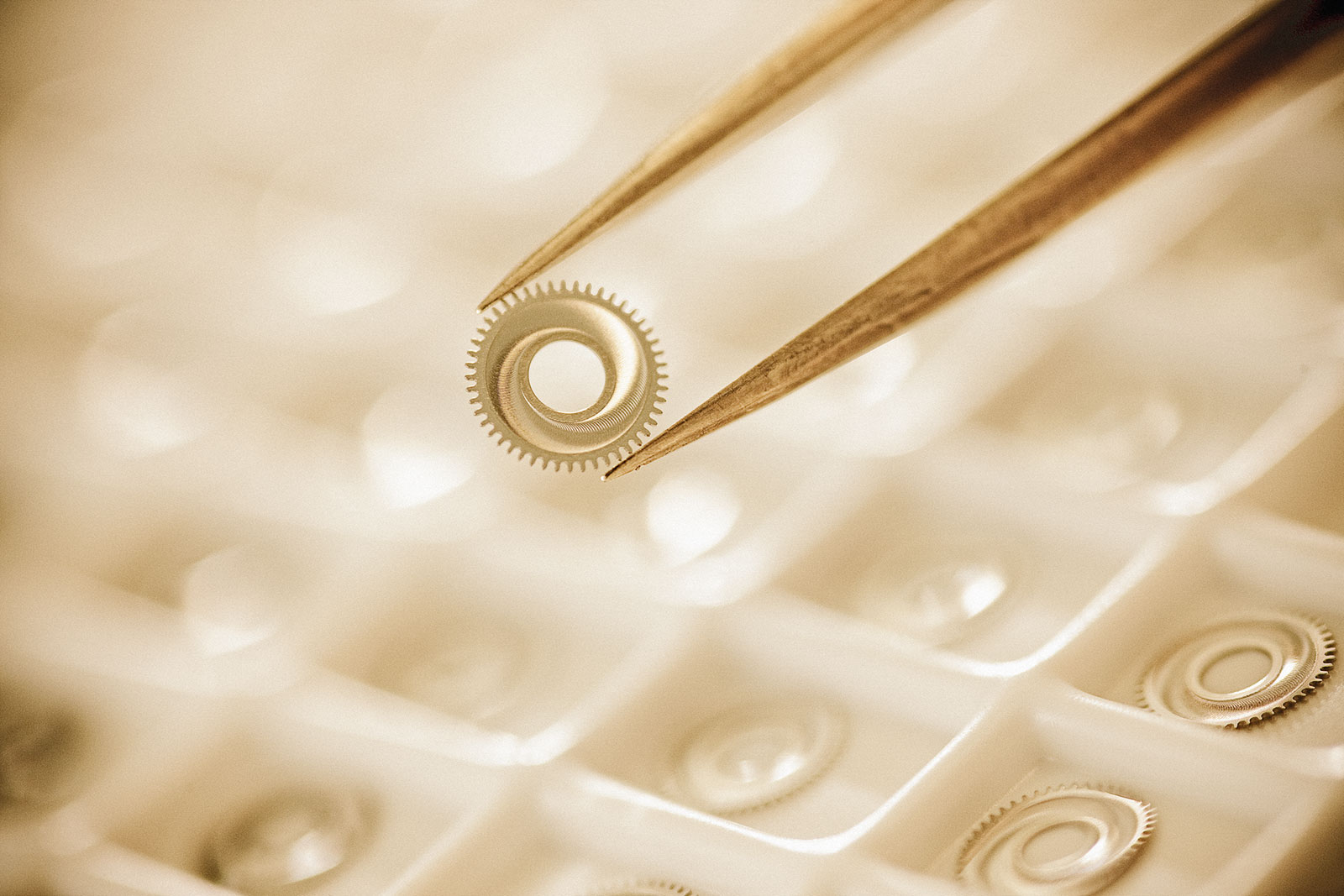

Decorated winding wheels

A more visible decorative technique done by hand is solarisation, resulting in a glimmering spiral polish on wheels, usually the barrel ratchet wheel. Less obvious but found throughout the movement are screw heads finished with speculaire or flat polishing. Several screws are mounted on a vice (that’s made by the toolmaking department naturally) that leaves the heads of the screws exposed. They are then polished on a tin plate covered in diamond paste by moving the vice in a figure of eight motion, until the screw heads are polished to a mirror-like finish. Tin polishing is also used to finish the curved swan neck regulator, which like the screws, is also stainless steel.

Flat polishing of screw heads

A swan neck after flat polishing

4. Plating to preserve

Given the degree of attention paid to decoration, preserving the finishing is vital. That’s where plating comes in. All the large, silvery parts of the movement like the three-quarter plate and rotor, are plated, first with nickel and then with either rhodium. A platinum group metal with a lustrous silver shine, rhodium-plated is the most common finish for watch movements, explaining the similar colour across brands and calibres.

Chemical baths for plating and galvanic coating

The gilded highlights against the rhodium background require additional work. Take for instance the hand-engraved balance cock: once the brass balance cock has been engraved, it is gold-plated and then entirely painted with protective lacquer known as masking. The masking is then polished off the flat surface of the balance cock, leaving the masked gold plating inside the engraved portions. Rhodium plating is then applied to the balance cock, covering all the surfaces except the masked engraving. In the final step the remaining masking is removed, resulting in a two-tone finish with the engraving highlighted in gold.

Applying masking on the rotor to create the two-tone finish

5. Trial by fire

A technique also used in high-end firearms and knives, bluing is another way to protect the finished component, usually stainless steel screws. Most screws in a Glashütte Original are heat treated to give them a distinctive blue colour, but instead of being done in large batches in an oven or a bath of boiling oil, screws are blued a handful at a time. They are carefully seated on the top of a soldering iron with tweezers and then heated to about 300°C. The heat forms an iron oxide layer on the surface of the screw, resulting in the blue tone that doubles up as a protective layer. Though simple in theory, the screws have to be scrutinised carefully and without distraction, because heating the screws a tad too long will turn them green and then grey.

Other steel components that need a little spring are tempered, with a spell in an oven then cooled. One of the most key visual components of the movement, the swan neck regulator, is treated in this manner, so as to increase the elasticity of the steel. This is important since the swan neck is constantly under tension, albeit only slightly.

Hardening the swan neck

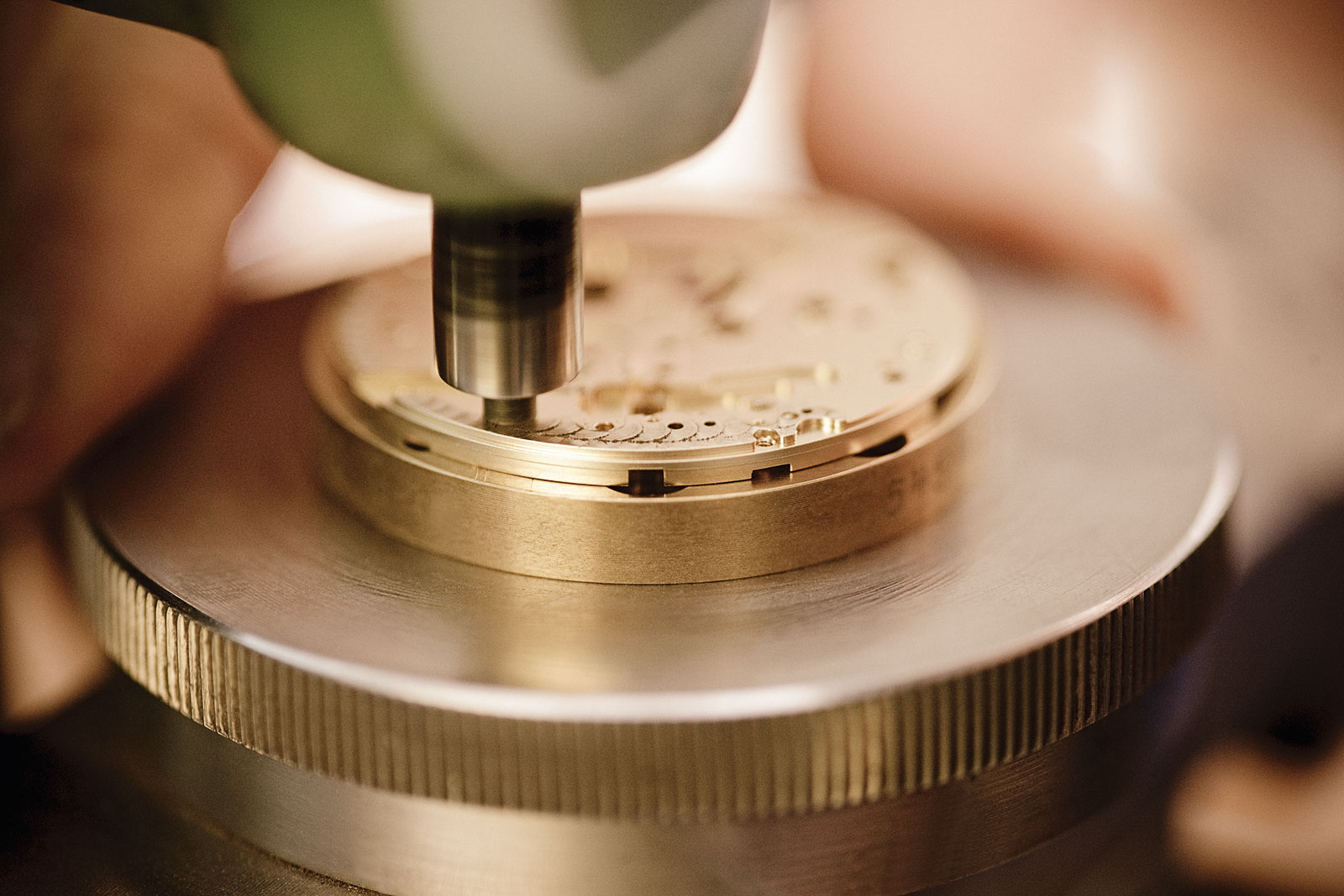

6. Sub-assembly

Once components have been properly gilded, blued or decorated, they are put together into subgroups – assembly of individual components into key sections of the movement. For example, the balance wheel (which comes from the rotary bar feeder) is completed by screwing individual screws into its rim, while the hairspring pinned to the balance cock. Putting the two together creates the balance assembly, which has to be poised. This is done with a machine creatively known as the Balance-O-matic that checks the balance of the balance, ensuring that it is equally weighted around its rim so that its oscillations are level and consistent. Small amounts of metal are milled out of the bottom surface of the balance wheel if necessary.

Other sections that are put together during subgroup assembly include the automatic winding mechanism (made up of gears, ball bearings and the rotor), date mechanism, and the barrel containing the mainspring. This step also includes pressing the jewels into the bridges.

7. Almost there

Assembled subgroups are then compiled into movement kits and sent to the assembly department, where watchmakers piece together the movement, add the dial and hands before putting it into the case. Regulation and testing of the completed watch is also performed, to ensure the watch works on the wrist as it did in the factory.

8. Complications

More complex timepieces, however, are put together in a separate department staffed by Glashütte Original’s crack watchmakers. While the process to complete the watch is just the same as for simpler timepieces, more care is needed due to the greater number of parts and correspondingly more tedious adjustment. Watches assembled in the complications section include the Cosmopolite world time, various tourbillons, Panographs, split-second chronographs and surprisingly, the Senator Diary alarm watch. While alarm watches are not usually regarded as highly complicated, the movement inside the Senator Diary comprises 631 parts, more than that inside a split-seconds chronograph.

So what does it all mean?

The definition of an in-house movement varies, and seemingly interchangeable terms like manufacture movement just increase the confusion. What is abundantly clear, having witnessed everything that takes place at Glashütte Original, is that its movements are definitely in-house, even by the strictest definition of the term.

But an in-house movement in itself is no guarantee of quality or effort; proper finishing and regulation is needed for that. Glashütte Original evidently does a good job of decorating its movements, in fact, its movements are finished as well as, or even better than, its peers in the same price segment.

And that is where Glashütte Original emerges with a gold medal. Its entry-level, men’s mechanical watches start at about US$7000, offering a lot of bona fide in-house goodness for the money.

Back to top.